Final Frontier Game: A Case Study on Learner Experience

Nour El Mawas

1

, Irina Tal

1

, Arghir Nicolae Moldovan

1

, Diana Bogusevschi

2

, Josephine Andrews

1

,

Gabriel-Miro Muntean

2

and Cristina Hava Muntean

1

1

School of Computing, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland

2

School of Electronic Engineering, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Gabriel.Muntean@dcu.ie, Cristina.Muntean@ncirl.ie

Keywords: Technology Enhanced Learning, STEM, Educational Video Game, Primary Education, and Solar System.

Abstract: Teachers are facing many difficulties when trying to improve the motivation, engagement, and learning

outcomes of students in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) subjects. Game-based

learning helps the students learn in an immersive and engaging environment, attracting them more towards

STEM education. This paper introduces a new interactive educational 3D video game called Final Frontier,

designed for primary school children. The proposed game design methodology is described and an analysis

of a research study conducted in Ireland that investigated learner experience through a survey is presented.

Results show that: (1) 92.5% of students have confirmed that the video game helped them to understand better

the characteristics of the planets from the Solar system, and (2) 92.6% of students enjoyed the game and

appreciated different game features, including the combination between fun and learning aspects which exists

in the game.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the advancements in technology and the need to

drive engagement and enquiry in STEM subjects,

there is an increased usage of game-based learning

pedagogy. This technology-based teaching pedagogy

is now applied at all levels of education, from primary

school to the third level education. In 2015, 47% of

K-12 teachers reported that they use game-based

learning in their classrooms, and almost 66% of K-5

teachers mentioned the use of digital games in their

curriculum (Doran 2016). Currently increasing

number of students are exposed to game-based

learning in their formal, non-formal and in-formal

education and this trend is expected to continue. For

instance, the TechNavio’s report published in August

2017 (TechNavio 2017) forecasts that K–12 game-

based learning market is expected to grow at a

compound annual growth rate of nearly 28 percent

during the period 2017-2021.

Game-based learning involves the use of gaming

technology for educative purposes where students

explore concepts in a learning context designed by

teachers. Game-based learning helps the students

learn in an immersive and engaging environment.

One aspect that made game-based learning usage so

popular is its ability to teach students how to solve

complex problems. Simple problems/tasks to be

solved are given to the player at the beginning of the

game and later on the tasks become progressively

more difficult, as the player is progressing in the

game and his/her skills and knowledge develop.

The growing importance of Science, Technology,

Engineering, Mathematics (STEM) education is also

driving the growth of game-based learning market.

This is due to the fact that educational games

encourage students to get involved in live projects or

real-time activities so that they can learn by

experimenting (Ravipati 2017). The game-based

learning pedagogy also boosts students’ confidence in

STEM-related subjects, increase their interest in

complex topics and helps teachers to deal with

disengagement of young people from STEM.

The new 21st century STEM teaching and

learning paradigm replaces the old approach in which

the teacher is the only source of all the knowledge,

everyone learns the same way, and the class is the

only place in which knowledge is transmitted. The

21st century teaching and learning paradigm is

dynamic, technology-enabled, student-centric and

develops 21

st

century competencies and skills such as

digital literacy, communication, collaboration,

122

El Mawas, N., Tal, I., Moldovan, A., Bogusevschi, D., Andrews, J., Muntean, G. and Muntean, C.

Final Frontier Game: A Case Study on Learner Experience.

DOI: 10.5220/0006716101220129

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 122-129

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

critical thinking, problem solving, decision making

and creativity.

In this context, the use of an educational game

creates engaging classrooms in STEM subjects,

demystifies the pre-conceived idea among students

that science and technologies subjects are difficult,

improves learning outcome and increases student

motivation and engagement.

The research work reported in this paper is

dedicated to STEM community and in particular to

researchers, and teachers in primary schools who

meet difficulties when engaging students in STEM

courses.

The paper presents of a research study on learner

experience when a new interactive educational 3D

video game called Final Frontier, designed for

primary school students, was used in the class. The

educational game delivers knowledge on two planets

from the Solar system: Mercury and Venus.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2

proposes the theoretical background of the study and

describes some existing educational games related to

the Solar system. Section 3 details our scientific

positioning, gives an overview of the Final Frontier

game and defines the game design methodology.

Section 4 presents research methodology of the case

study and its results. Section 5 summarizes the paper,

draws conclusions regarding the research study

performed and presents future perspectives.

2 RELATED WORK

Game-based learning (GBL) represents an

educational approach that integrates video games

with defined learning outcomes. The appeal of using

video games in education can be partially explained

by the need to reach today’s digital learners that have

continuous access to entertainment content through

the Internet. At the same time, games provide highly

engaging activities that are stimulating, generate

strong emotions, require complex information

processing, provide challenges and can support

learning and skill acquisition (Boyle, Connolly, and

Hainey, 2011). The learning experiences and

outcomes of educational games can be classified into

several classes which include: knowledge acquisition,

practising and processing (content understanding),

knowledge application (skill acquisition), reflection

(behaviour change) and knowledge anticipation

(motivation outcomes) (Jabbar and Felicia, 2015).

Previous research works have shown that game-

based learning can have positive effects on important

educational factors such as student motivation and

engagement (Ghergulescu and Muntean, 2012,

Ghergulescu and Muntean, 2010a), learning

effectiveness (Erhel and Jamet, 2013), as well as

learning attitude, achievement and self-efficacy

(Sung and Hwang, 2013, Ghergulescu and Muntean,

2016). Moreover, game-based learning has the

potential to facilitate the acquisition of 21

st

century

skills such as critical thinking, collaboration,

creativity and communication (Qian and Clark,

2016). While there is much research evidence of GBL

benefits, some studies failed to reproduce them or

obtained contradictory findings. Tobias et al., argue

that this may be due to lack of design processes that

effectively integrate the motivational aspects of

games with good instructional design to ensure

learners acquire the expected knowledge and skills

(Tobias, Fletcher, and Wind, 2014). The authors also

made recommendations for educational game design,

such as to provide guidance, use first person in

dialogues, use animated agents in the interaction with

players, use human rather than synthetic voices,

maximise user involvement and motivation, reduce

cognitive load, integrate games with instructional

objectives and other instruction, use teams to develop

instructional games (Tobias et al., 2014).

One common criticism of game-based learning

studies is that they lack foundation in established

learning theories. A meta-analysis of 658 game-based

learning research studies published over 4 decades,

showed that the wide majority of studies failed to use

a learning theory foundation (Wu, Hsiao, Wu, Lin,

and Huang, 2012). Among the studies that had a

pedagogical foundation, constructivism appears to be

the most commonly used as indicated by multiple

review papers (Li and Tsai, 2013; Qian and Clark,

2016; Wu et al., 2012). Other learning theories that

were also implemented by different research studies

include: cognitivism, humanism and behaviourism.

Common learning principles employed by game-

based learning studies include among others:

experiential learning, situated learning, problem-

based learning, direct instruction, activity theory, and

discovery learning (Wu et al., 2012).

Few studies have proposed and/or evaluated

educational games related to planets or the solar

system (Muntean and Andrews, 2017). HelloPlanet is

a game where the player can observe and interact with

a planet that has a dynamic ecosystem, where the

player can simulate organisms, non-organisms,

terrains, and more (Sin et al., 2017). The game

evaluation results from 41 primary and secondary

school children, showed a statistically significant

learning gain for both girls and boys, and an effect on

interest in STEM for girls, but not for boys. The

Final Frontier Game: A Case Study on Learner Experience

123

Space Rift game enables students to explore the Solar

system in a virtual reality environment (Peña and

Tobias, 2014). However, the game evaluation

involved only 5 students and was mostly focused on

usability rather than educational aspects. The Ice

Flows game aims to educate the users about the

environmental factors such as temperature and

snowfall on the behaviour of the Antarctic ice sheet

(Le Brocq, 2017). However, the game was either not

evaluated or the results were not published yet.

A recent systematic review of game-based

learning in primary education has indicated that

games were used to teach a variety of subjects, among

which the most popular being Mathematics, Science,

Languages and Social Studies (Hainey et al., 2016).

However, the review authors also concluded that

more research studies are needed to evaluate the

pedagogical benefits of GBL at primary level.

In this context, our research contributions are as

follows: (i) proposal of an extended educational

games design methodology, (ii) development of the

Final Frontier educational game for teaching Solar

system planets-related concepts, a topic that was not

thoroughly covered by previous research studies, and

(iii) evaluation of the game benefits when deployed

to target primary school students.

3 THE FINAL FRONTIER GAME

3.1 Game Description

Final Frontier is an interactive 3D educational video

game about space for children up to 12 years old. The

game supports knowledge acquisition on Solar

system planets (i.e. Mercury and Venus were targeted

in this study) through direct experience, challenges

and fun. The topics coved by the game are part of the

Geography curriculum, section “Planet Earth and

Space”, defined for the primary school in Ireland. The

game has different levels, each level containing

different models and landscapes. In each level, the

game requires meeting a game objective (i.e.

mission), collection of stars and meteorites and has

constrains e.g. coolant time. Information regarding

the number of stars and meteorites collected, coolant

time and game level mission is displayed on the

screen.

Once a level is completed, the player must answer

correctly a multi-choice question in order to be able

to progress to the next level. The player is allowed to

try to answer the question multiple times if a wrong

answer is provided.

The game starts by bringing the player on a

spaceship where he game mission is explained. There

are two activities that the player has to complete

during the first activity, the player is instructed to visit

the first planet, Mercury. The game goal related to

this planet is to explore the environment and to collect

five meteorites hidden in the craters that exist on

Mercury (see Figure 1). The player may use the

jetpack to get in and out of the craters. An avatar

provides extra information (facts) about the planet

during the play time.

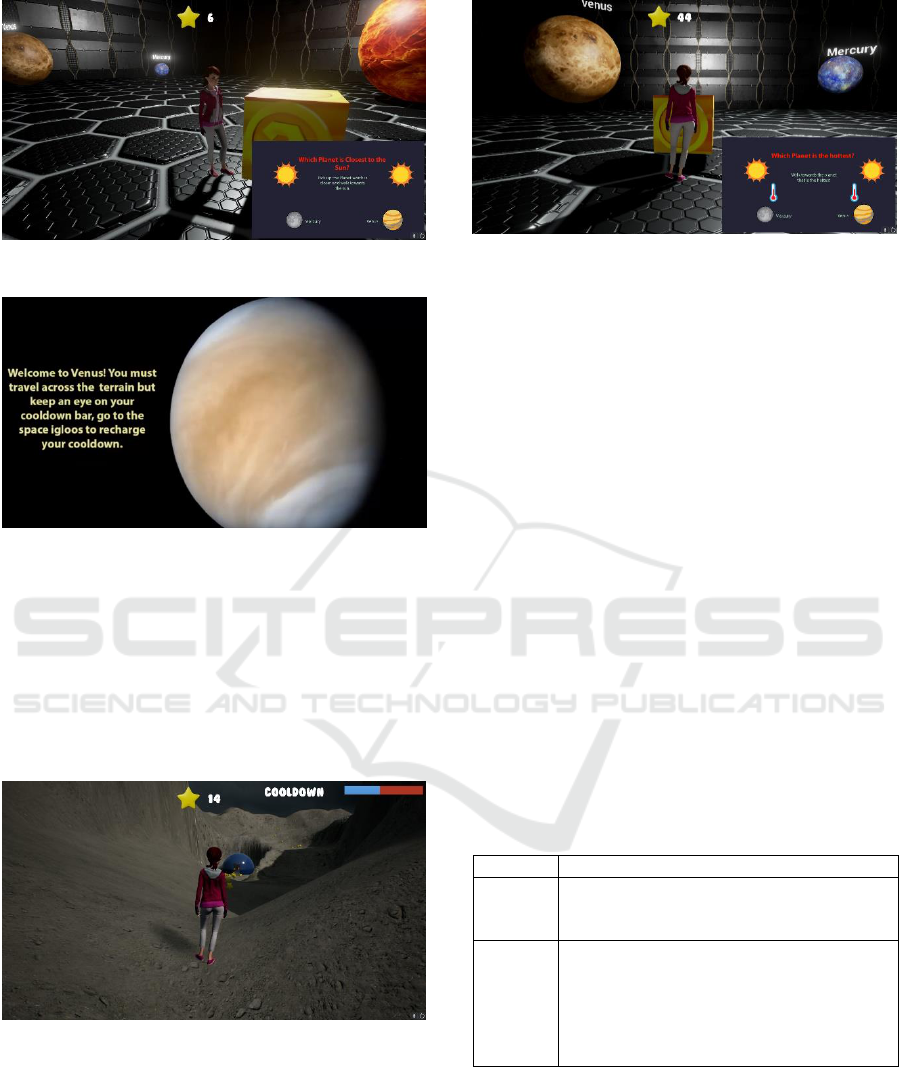

Figure 2 illustrates how the level mission as well

as the number of meteorites and stars a player has

collected are displayed on the screen for the entire

duration of playing a level.

Once the mission on Mercury was completed, the

player returns to the spaceship, in the puzzle room

where he/she must answer a question (e.g. What is the

closest planet to the Sun?).

Figure 1: The goal of the mission to Mercury.

Figure 2: The player using jetpack on Mercury.

A screenshot of this game activity is presented in

Figure 3. The aim of this mini quiz is to check

player’s knowledge about Mercury. The player

interacts with the game environment when answering

the question by picking up the correct object (e.g.

planet Mercury) and placing it beside the Sun.

Once this question is answered correctly, the

player is awarded a key that is used to open a door on

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

124

Figure 3: Puzzle room and the question about Mercury.

Figure 4: The objective of the mission to Venus.

the spaceship and progress to the next level.

The second level is associated with another

activity which requires the player to explore the

planet Venus and complete a given task. The mission

is to traverse the Venus environment without letting

their cooldown bar get to zero. Buildings called igloos

may be used to recharge their coolant supply (see

Figure 4).

Figure 5: The player on Venus planet.

Next, the player is teleported to the Venus planet

surface. There are four buildings (igloos) that the

player may enter while crossing the terrain. The

cooldown bar depletes when traversing the planet

surface, which is very hot (Figure 5), but regenerates

when the player enters any of the buildings. While

traversing the terrain, the player may collect stars that

Figure 6: Puzzle room and the question about Venus.

are added up to the overall stars score. Facts about

Venus are displayed during the play time.

Once the player reaches the fourth igloo, he/she is

returned to the spaceship, into the puzzle room and

asked to complete the second puzzle. A multi-choice

question about Venus (see Figure 6) must be

answered correctly in order to complete this level.

The puzzle asks the player to identify which

planet is the hottest in the Solar system. Three planets

are displayed. The player must walk towards the

planet that represents the correct answer. Once this is

done the game is complete. The overall number of

collected starts is also displayed.

3.2 Game Design Methodology

The methodology for designing the Final Frontier

game is based on that described in (Marfisi et al.,

2010). However, two steps related to the learning

puzzle such as the general description of the learning

puzzle and detailed description of the learning puzzle

were added.

Table 1: LOs of the Final Frontier game.

Planet

LOs

Mercury

- Closest planet to the sun (LO1)

- Planet with the most craters (LO2)

- Smallest planet (LO3)

Venus

- Hottest planet due to the greenhouse effect

(LO1)

- Spins opposite direction to Earth

(LO2)

- High Gravity cannot jump very high

(LO3)

The authors believe that recall is a very important

step in the learning process. Moreover, the

recommendations on efficient game design proposed

by (Tobias et al., 2014) were taken into account.

The game design methodology proposed in this

research is composed of the following steps:

specification of the pedagogical objectives,

choice of the game model,

Final Frontier Game: A Case Study on Learner Experience

125

general description of the scenario and virtual

environment,

general description of the learning puzzle,

choice of a software development engine,

detailed description of the scenario,

detailed description of the learning puzzle,

pedagogical quality control, and

game distribution.

Specification of the pedagogical objectives: the

proposed 3D interactive educational game shall be

used to teach concepts on the solar system in primary

schools. The first step of the conception phase

consists of defining the concepts that must be learned

by the students. For this reason, the authors worked

with teachers from European primary schools that

teach the Geography subject to make sure that the

designed game covers the required topics specified in

the curriculum. The pedagogical objectives of the

game were defined and presented in Table 1.

Choice of the game model: Once the pedagogical

objectives were defined, Adventure was selected as

the game model for the Final Frontier. The Adventure

game model involves the player assuming the role of

the protagonist in the game, exploring the

environment and completion of puzzles in order to

progress. Collectable objects such as stars and

meteorites are also included. The jetpack allows the

player to go higher than the jump. The puzzle

embedded in the game requires the player to complete

various tasks in order to progress through the game.

The collectable stars are used to guide the player and

encourage him/her to explore the environment. The

meteorites are used on the Mercury planet as a

collectable to gauge the players’ progress. The

cooldown feature is used on Venus and gives the

player a challenge, as they go through the level.

The game design has considered three areas: the

spaceship where the game starts and finishes and

where the player goes back to after visiting a planet;

planet Mercury which the player visits during the first

activity; and planet Venus that hosts the second

activity to be completed.

The Adventure game model is one of the most

popular among children. The children get more

immersed and motivated when they play adventure

games over other types. Moreover, the Adventure

game model involves a linear story that can be easily

defined in the game. Various gameplay features such

as jetpack, puzzle solving, collectable stars and

meteorites, cooldown bar were also defined in this

game mode.

General description of the scenario and virtual

environment: the aim of this part is to structure the

pedagogical scenario and match it up with a fun based

scenario. The main focus was to make the game

familiar to the learners. The characters are simple

human characters so the player can easily interact

with. The story of the game is that the player is on a

field trip, and he/she visits some planets. The player

is assigned a task to do on each planet and learns

implicitly facts about the planet while playing.

General description of the learning puzzle:

When the player completes a given task, he/she is

brought back to the spaceship to solve a puzzle and

when successful, to progress to the next level. The

puzzle learning was added because it was believed

that active recall is a principle of efficient learning.

Many studies demonstrate the role of active recall in

consolidating long-term memory e.g. (Spitz, 1973).

Choice of a software development engine:

concerning the game development engine, Unreal

Engine 4 or Unity, two of the most popular game

development engines, can be used. Unreal Engine 4

was used in this game development due to its graphic

potential, especially as it was aimed to give to the

player the most realistic environment of the planets.

Detailed description of the scenario: this step

involves the illustration of each scene with all the

details and interactions to be integrated into the game.

Detailed description of the learning puzzle: the

game has two puzzles that correspond to the two

planets. Once the puzzle is answered correctly the

player is allowed to go to the next planet. The player

is allowed to try to answer the puzzle multiple times

if a wrong answer was given.

Pedagogical quality control: the developed

game was shown to the teacher to validate it and to

approve the pedagogical quality of the game.

Feedback was considered and the game was

improved.

Game distribution: Once the teacher was

satisfied and the game was approved, the game was

ready to be distributed to the students in the class.

4 CASE STUDY

The goal of the research study was to investigate

learner experience when the Final Frontier game was

used in the class to teach scientific knowledge of the

planets from the Solar system to primary school

children.

This section presents the evaluation methodology

applied, case study set-up and results analysis for of

the collected data.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

126

4.1 Research Methodology

The evaluation included a group of children who were

taught by using the Final Frontier game. The learning

activity took place in class, during the normal hours

of study. A total of 53 children of age 9-10 years from

Saint Patrick Boys National School located in Dublin,

Ireland took part in the case study. Team members

from the National College of Ireland and Dublin City

University (DCU) have prepared and helped perform

the tests.

The evaluation meets all Ethics requirements.

Prior to running the case study, the Ethics approval

was obtained from the DCU Ethics Committee and all

required forms were provided to the children and their

parents, including informed consent form, informed

assent form, plain language statement and data

management plan. These documents include a

detailed description of the testing scenario, as well as

information on study purpose, data processing and

analysis, participant identity protection, etc.

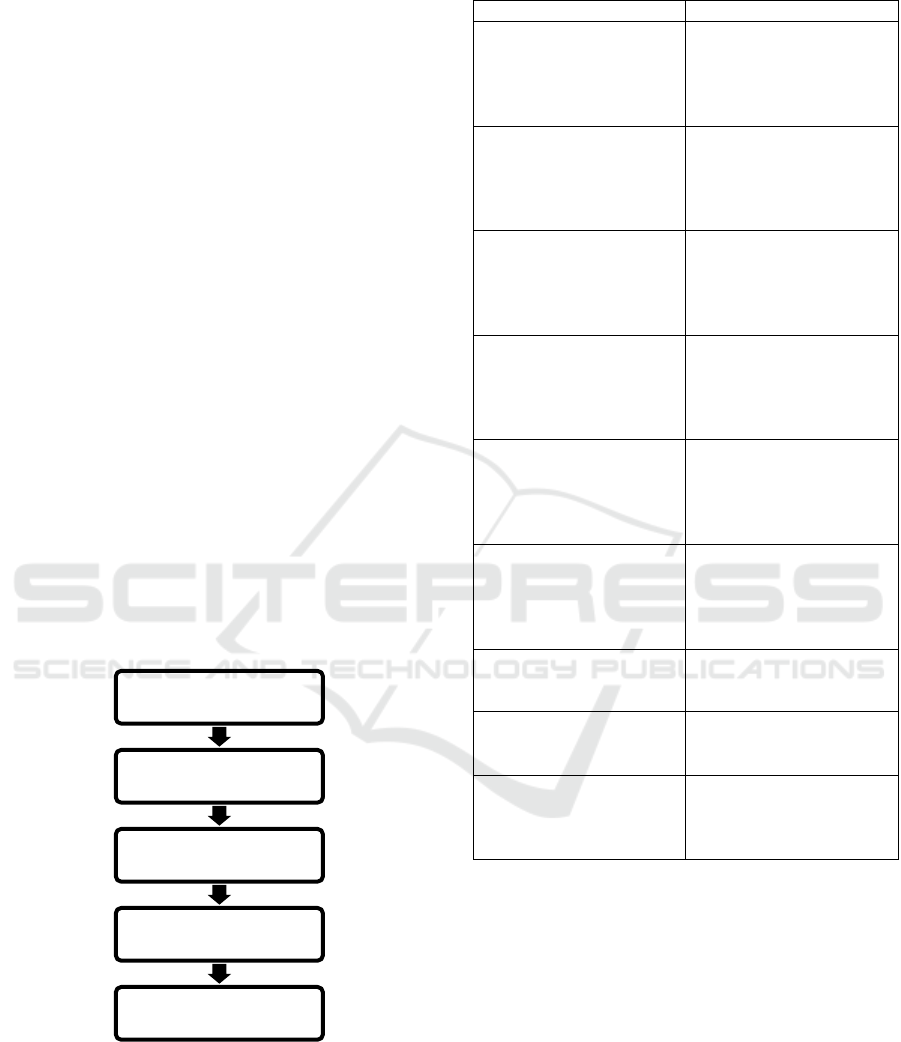

The flow of the evaluation is illustrated in Figure

7 that presents in details the steps followed by the

researchers. It can be seen that prior to beginning the

evaluation, the consent forms signed by parents were

collected. Then the children were introduced to the

research case study and asked to review and sign the

assent form. The children had roughly 20 minutes to

play the game or till they finished the game before

doing a survey.

Figure 7: Evaluation process.

The case study investigated the learner experience

with the game and the game usability. A learner

satisfaction questionnaire assessing student level of

experience and game usability was collected.

Table 2: Survey questions.

Question

Answer/Scale

Q1. The video game

helped me to better

understand the

characteristics of different

planets.

- Strongly Disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly Agree

Q2. The video game

helped me to learn easier

about planets.

- Strongly Disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly Agree

Q3. I enjoyed this lesson

that included the video

game on planets.

- Strongly Disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly Agree

Q4. The quizzes that I did

in the game helped me

better remember what I

learned.

- Strongly Disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly Agree

Q5. The video game

distracted me from

learning.

- Strongly Disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly Agree

Q6. I would like to have

more lessons that include

video games.

- Strongly Disagree

- Disagree

- Neutral

- Agree

- Strongly Agree

Q7. What did you like

most about the game?

Students to provide

their feelings toward the

experience

Q8. Comments /

Suggestions (optional)

Students to provide

their comment if they

wished

Q9. What way of learning

you would like (tick one

answer)?

- Teacher based learning

- Computer game based

learning

Standard emojis were associated with each answer to

the questionnaire’s questions.

4.2 Results Analysis

4.2.1 Learner Experience

Learner experience in using the Final Frontier game

was investigated and evaluated by questions Q1 to Q6

in the survey. The experience was analysed in terms

of number of Strongly Agree / Agree answers for Q1,

Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q6 and Strongly Disagree / Disagree

for Q5.

Collection of the consent

forms (signed by the parents)

Description of the research

study

Collection of assent forms

Learning experience

Survey

Final Frontier Game: A Case Study on Learner Experience

127

Table 3: Children answers on the user experience survey.

SD

D

N

A

SA

Q1

0

0

7.5%

60.5%

32%

Q2

0

0

11.2%

45.4%

43.4%

Q3

0

0

1.9%

19.1%

79%

Q4

0

1.9%

13.2%

52.9%

32%

Q5

45.4%

24.7%

15%

3.7%

11.2%

Q6

1.9%

0

1.9%

7.5%

88.7%

The overall learner experience of children was

excellent (see Table 3). 92.5% of children confirmed

that the video game helped them to better understand

the characteristics of the two planets. 88.8% of

children thought that the video game helped them to

learn easier about planets. 98.1% of students enjoyed

the lesson that included the video game. 84.9% of

children agreed on the fact that quizzes embedded in

the game helped them better remember what they

have learned. 70.1% of children disagreed that the

video game distracted them from learning. 96.2% of

children expressed that they would like to have more

lessons that include video games.

Note that for clarity reasons, in Table 3, SD refers

to Strongly Disagree, D refers to Disagree, N refers

to Neutral, A refers to Agree, and SA refers to

Strongly Agree.

4.2.2 Game Usability

The game usability of the Final Frontier was also

analysed through Q7, Q8 and Q9 from the survey.

An analysis of the answers provided for Q7 and

Q8 shows that 92.6% of children mentioned that they

have enjoyed the game, in particular the fun aspect,

learning aspects, stars and meteorites collection,

avatar, use of jetpack, and interactive puzzle room.

Regarding Q9, 94% of children mentioned that

they prefer computer game-based learning during the

normal teaching class, which is an outstanding result

for the deployment of this game.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study addresses the problem of motivating,

engaging, and improving learning experience of

students in the STEM field. A novel 3D interactive

video game (Final Frontier) was designed and tested

with children from a Dublin-based primary school.

The game supports knowledge acquisition about two

Solar system planets: Mercury and Venus through

direct experience, active recall, challenges and fun.

The game design methodology of Final Frontier

was described in this paper. An analysis of the results

collected in a case study conducted on a group of 57

students was also presented in the paper. Learner

experience with the game, and game usability were

investigated through a survey. An analysis of the

survey questionnaire results shows that a large

majority of children were satisfied with the game

usability: 92.6% of children enjoyed the game. The

survey also shows that children have appreciated

various game features including the fun aspect,

learning aspects, stars and meteorites collection,

avatar, use of jetpacks, and interactive puzzle room

that existed in the game.

The overall learner experience of children was

excellent, 92.5% of children confirmed that the game

helped them to learn better about the two planets.

Future work will aim to expand the research study

on the Final Frontier game as well as on the game

methodology. Further research will include all planets

of the Solar system to the game. The learning impact

of the game will also be assessed.

Research has shown the benefits of integrating

adaptation based on learner quality of experience and

learner profile in the learning process (Muntean et al.

2006, Muntean et al. 2010b).

Thus, the adaptive feature will also be designed

and developed in the game in order to address the

problem of learners’ diversity, their difference in

terms of prior knowledge and learning experience.

The Final Frontier 3D interactive computer game

introduced in this paper will be deployed through the

NEWTON platform (NEWTON 2016) and tested in

different European primary schools. Case studies that

will investigate the benefits of the educational game

in different European schools will be organized and

an analysis of the results across countries will be

performed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by the NEWTON project

(http://www.newtonproject.eu/) funded under the

European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and

Innovation programme, Grant Agreement no.688503.

REFERENCES

Boyle, E., Connolly, T. M., & Hainey, T. (2011). The role

of psychology in understanding the impact of computer

games. Entertainment Computing, 2(2), 69–74.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2010.12.002

Erhel, S., & Jamet, E. (2013). Digital game-based learning:

Impact of instructions and feedback on motivation and

learning effectiveness. Computers & Education,

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

128

67(Supplement C), 156–167.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.02.019

Ghergulescu, I., & Muntean, C. H. (2012). Measurement

and Analysis of Learner’s Motivation in Game-Based

E-Learning. In D. Ifenthaler, D. Eseryel, & X. Ge

(Eds.), Assessment in Game-Based Learning (pp. 355–

378). New York, NY: Springer New York. Retrieved

from http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-

4614-3546-4_18?null

Ghergulescu, I., & Muntean, C. H. (2010a). Assessment of

motivation in games based e-learninf. IADIS

International Conference Cognition and Exploratory

Learning in Digital Age (CELDA 2010), Timisoara,

Romania, pp.71-78

Ghergulescu, I., & Muntean, C. H. (2010b) “MoGAME:

Motivation based Game Level Adaptation

Mechanism”, in the 10th Annual Irish Learning

Technology Association Conference (EdTech 2010)

Athlone, Ireland

http://www.ilta.net/files/EdTech2010/R2_Ghergulescu

Muntean.pdf

Ghergulescu, I., & Muntean, C. H (2016). ToTCompute: A

Novel EEG-based TimeOnTask Thresholds

Computation Mechanism for Engagement Modelling

and Monitoring, International Journal of Artificial

Intelligence in Education, Special issue on ‘User

Modelling to Support Personalization in Enhanced

Educational Setting, pp 1-34, April 2016

Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Boyle, E. A., Wilson, A., &

Razak, A. (2016). A systematic literature review of

games-based learning empirical evidence in primary

education. Computers & Education, 102(Supplement

C), 202–223.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.09.001

Jabbar, A. I. A., & Felicia, P. (2015). Gameplay

Engagement and Learning in Game-Based Learning A

Systematic Review. Review of Educational Research,

85(4), 740–779.

https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315577210

Le Brocq, A. (2017). Ice Flows: A Game-based Learning

approach to Science Communication (Vol. 19, p.

19075). Presented at the EGU General Assembly

Conference Abstracts. Retrieved from

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017EGUGA..1919075

L

Doran, L. (2016). Games, Videos Continue to Make Big

Gains in Classrooms, Survey Finds. Education Week -

Digital Education. May 12.

Li, M.-C., & Tsai, C.-C. (2013). Game-Based Learning in

Science Education: A Review of Relevant Research.

Journal of Science Education and Technology, 22(6),

877–898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-013-9436-x

Marfisi-Schottman I., George S., Tarpin-Bernard F. (2010)

Tools and Methods for Efficiently Designing Serious

Games. Proceedings of 4th Europeen Conference on

Games Based Learning, Copenhagen, Denmark, p.

226-234.

Muntean C.H, Andrews, J. (2017), Final Frontier: An

Educational Game on Solar System Concepts

Acquisition for Primary Schools, 17th IEEE

International Conference on Advanced ( ICALT),

Timisoara, Romania

Muntean C.H., McManis, J. (2006). End-user Quality of

Experience oriented adaptive e-learning system.

Journal of Digital Information, Vol. 7, No. 1

NEWTON (2016), “H2020: Networked Labs for Training

in Sciences and Technologies for Information and

Communication,” 2016. [Online]. Available:

http://www.newtonproject.eu/.

Peña, J. G. V., & Tobias, G. P. A. R. (2014). Space Rift: An

Oculus Rift Solar System Exploration Game.

Philippine Information Technology Journal, 7(1), 55–

60.

Ravipati (2017). Trends: STEM Game-based Learning to

See Surge in Immersive Tech. The Journal, August

2017.https://thejournal.com/articles/2017/08/29/trends

-game-based-learning-market-to-see-surge-in-

immersive-tech.aspx

Qian, M., & Clark, K. R. (2016). Game-based Learning and

21st century skills: A review of recent research.

Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 50–58.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.023

Sin, Z. P. T., Ng, P. H. F., Shiu, S. C. K., & Chung, F. l.

(2017). Planetary marching cubes for STEM sandbox

game-based learning: Enhancing student interest and

performance with simulation realism planet simulating

sandbox. In 2017 IEEE Global Engineering Education

Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 1644–1653).

https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2017.7943069

Spitz, H.H., Consolidating facts into the schematized

learning and memory system of educable retardates,

dans N.R. Ellis (éd.), International review of research

in mental retardation, vol. 6, New-York: Academic

Press, 1973.

Sung, H.-Y., & Hwang, G.-J. (2013). A collaborative game-

based learning approach to improving students’

learning performance in science courses. Computers &

Education, 63(Supplement C), 43–51.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.019

TechNavio (2017). Global K-12 Game-based Learning

Market 2017-2021, August 2017,

https://www.researchandmarkets.com/research/h6m4w

j/global_k12

Tobias, S., Fletcher, J. D., & Wind, A. P. (2014). Game-

Based Learning. In Handbook of Research on

Educational Communications and Technology (pp.

485–503). Springer, New York, NY.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_38

Wu, W.-H., Hsiao, H.-C., Wu, P.-L., Lin, C.-H., & Huang,

S.-H. (2012). Investigating the learning-theory

foundations of game-based learning: a meta-analysis.

Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(3), 265–

279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00437.x

Final Frontier Game: A Case Study on Learner Experience

129