Orthographic Educational Game for Portuguese Language Countries

Paula Chaves, Luan Paschoal, Tauan Velasco, Tiago Bento,

Julliany Brand

˜

ao, Carlos Schocair, Jo

˜

ao Quadros, Talita Oliveira and Eduardo Ogasawara

Federal Center for Technological Education of Rio de Janeiro - CEFET/RJ, Brazil

Keywords:

Orthography, Game, Learning, Orthographic Agreement.

Abstract:

The new orthographic agreement introduces some changes in the vocabulary of the Portuguese language.

Although these changes have modified a small percentage of the vocabulary words, people are struggling to

adapt to some of the new orthographic rules. Aiming to mitigate this problem using a ludic approach, we

developed Orthographic Educational Game (JOE). JOE focuses predominantly on the rules of accents and

hyphens. The game is divided into two modes: training and playing. In the playing mode, the current level

of knowledge of the player in orthography is checked and measured. In the training mode, each word comes

with a hint related to the rule that is being practiced at the moment. The game was evaluated through an

experiment with both undergraduates and high school students. The results indicated that more than 80% of

students enjoyed learning orthography through the game-based approach of JOE.

1 INTRODUCTION

The new Orthographic Agreement has the objective

of aid the cultural and political exchange among all

countries that are part of the Community of the Por-

tuguese Language Countries (CPLP). The mandatory

adoption of new orthographic rules in Brazil was

scheduled to start in December of 2012, but it was

postponed until January of 2016 to align with the

schedule of other countries. The Ministry of Educa-

tion has encouraged the adoption of new orthographic

rules since the beginning through earlier adjustments

of school books. Although the estimated changes

in the vocabulary of the Portuguese language do not

go beyond 2% (Garcez, 1993), students still experi-

ence difficulties in adapting to some of the new ortho-

graphic rules.

Primarily this occurs due to two main reasons.

The first one is a large number of words that are

exceptions to the orthographic rules. The second is

the complexity of some orthographic rules. In some

cases, these reasons may be combined, such as the

case of the hyphen. The general concept is that hy-

phen serves to connect elements forming words com-

posed by juxtaposition and connect prefixes and suf-

fixes to radicals. However, this concept is detailed in

a set of rules that are hard to follow and with many

exceptions (Ganho and McGovern, 2004).

In many cases, students try to memorize the rules

and exceptions. However, the traditional approach of

memorizing subjects is no longer attracting students.

Thus, new ways of teaching and practicing are in-

creasingly needed (Dom

´

ınguez et al., 2013). Educa-

tional games are becoming a complementary option

to address this type of problem. It is a motivating tool

for learning in today’s society. The use of educational

games has shown effectiveness in many studying sit-

uations. It is a way of exercising the activities in a

ludic way. Thus, enhancing creativity and attention

of students (Papastergiou, 2009).

In this paper, we present an Educational Game

(JOE). The primary purpose of JOE is to aid people

to adopt the new orthographic rules, by focusing on

the accents and hyphen rules through a game-based

approach. We intend to answer two research ques-

tions: (i) Is JOE able to support teaching accents and

hyphen rules? (ii) Is JOE able to make students mo-

tivated and to enable them to learn the new ortho-

graphic rules? JOE was designed for Android plat-

form and is available for free at Google Play Store.

We have conducted an experimental evaluation with

two sets of students (high-school and undergraduate

students). Students filled a questionnaire both before

and after the training. It was possible to measure the

number of hits and errors both before and after using

JOE. The experiments also evaluated the user inter-

action with the game, which enables to measure both

learning and motivation of the student to play again.

The remainder of the paper is organized as fol-

432

Chaves, P., Paschoal, L., Velasco, T., Bento, T., Brandão, J., Schocair, C., Quadros, J., Oliveira, T. and Ogasawara, E.

Orthographic Educational Game for Portuguese Language Countries.

DOI: 10.5220/0006757504320440

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 432-440

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

lows. Specifications and agreements of Portuguese

usage are reviewed in Section 2. Section 3 contains

related work, whereas Section 4 explains JOE. Com-

putational experiments are reported and discussed in

Section 5. Concluding remarks are drawn in Section

6.

2 NEW ORTHOGRAPHIC

AGREEMENT

The discussion of this New Portuguese Orthographic

Agreement seems recent, but it refers to the early

twentieth century. The first Orthographic Agreement

was approved in 1931 when, at the initiative of the

Brazilian Academy of Letters, in consonance with the

Lisbon Academy of Sciences, decided to create a ref-

erence model for the official publications and teach-

ing (Garcez, 1993). At that time, however, Brazilian

government did not join the initiative.

After several failed negotiations among all the

countries of Lusophone (Garcez, 1993), nearly six

decades later (in 1990), the new Orthographic Agree-

ment was created in Lisbon (Portugal). It was ap-

proved five years later but only came into force in

2009.

This change in the orthographic rules arose from

the attempt to unify the orthography between the

countries of the CPLP, formed by Brazil, Portugal,

Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde,

East Timor, Sao Tome, and Principe (Ackerlind and

Jones-Kellogg, 2011).

To assist in the transition of orthographic reform,

the Educational Complex of the United Metropoli-

tan Colleges, in partnership with the Museum of the

Portuguese Language, launched the Orthographic Re-

form Guide (Ganho and McGovern, 2004). The pe-

riod of transition for adopting the new orthographic

rules would be up to 2013 for most countries of the

agreement. However, in Brazil, the mandatory adop-

tion was extended to 2016. It should be emphasized

that although the orthographic reform pass to be uni-

fied, the pronunciation and vocabulary of each coun-

try does not change (Almeida et al., 2010).

3 RELATED WORK

The game-based approach use features and game

principles to ease learning and problem-solving. The

game motivates players to continue to meet the chal-

lenges of the next phase. In an educational game, the

content of the studied subject need to be related to

the theme of the game, showing examples from ev-

eryday life. The game should allow for students to

gain the necessary skills for each new lesson (phase).

The presence of phases is one of the characteristics

that define a game. They usually start easier and the

complexity increases according to the skills and expe-

rience gained. In the process of rewards, for example,

it is interesting, when players fail, show them where

they went wrong and to encourage them in the search

for recovery (De Sousa Borges et al., 2014).

Some classic games that involve orthography in-

clude Hangman (Madeo, 2011), Word Search (Diah

et al., 2010), Crosswords Puzzle (Leow, 2001), and

Spell Up. These games have a ludic aspect and of

the reward, which encourages students to study more,

but, in its essence, is not intended to teach, nor to

explain the grammatical rules involved. In computer

games, there is a broad range of projects. In the con-

text of JOE, it is worth mentioning seven: Alfagame,

Duolingo, Babbel, Busuu, O que vem a seguir, Sole-

trandoMob, OrtograFixe, AmarganA, Grapphia, Na

Ponta da L

´

ıngua, and Novel.

Alfagame (Netto and Santos, 2012) is an educa-

tional game designed for children in the literacy pro-

cess. The objective of the game is to allow students to

reinforce the contents previously learned in the Math-

ematics and Portuguese language through play. The

contents are addressed through challenges, exploiting

the fixing of students in recognition of consonants,

vowels, and word association, as well as resolutions

of math addition and subtraction. The game can be

downloaded from authors website and is designed for

Windows.

Duolingo (Munday, 2017), Babbel (Parejalora

et al., 2016), and Busuu (

´

Alvarez Valencia, 2016) are

similar applications. They have as primary objective

to enable users to learn a foreign language interac-

tively and apply game-play trend that has been gain-

ing strength in recent years. Just as today’s games,

there is an interaction with social networks to encour-

age players to compete with each other and continue

playing. In addition to social networking, there is

also an internal system in which players can post on

a friend’s wall, discuss a lesson that was not under-

stood, reporting an error in translation, among other

things.

O que vem a seguir is a software designed for

Windows. The game aims to show the use of digital

educational games as a way of promoting the assimi-

lation of content and sharing student’s interest in edu-

cational tasks. It requires a responsive attitude, which

only occurs when individuals seek to understand the

facts actively by their knowledge of the learning ob-

ject (Ara

´

ujo et al., 2012). Soletrandomob is an ap-

Orthographic Educational Game for Portuguese Language Countries

433

plication designed for Android. The game shows the

sound of a word and the player must spell it correctly

and may ask for tips, like the use of the word in a sen-

tence. Such tip is an attempt to help the player by en-

tering the word in the context of interpretation. In the

end, it shows the number of correct answers during

the execution of the game. Also, in case of errors, it

shows messages with the right word (Santos and oth-

ers, 2010). OrthograFixe (Marques and Silva, 2012)

is a game where features words move up and down at

different speeds. The user must press the word that is

spelled correctly. The game treats hyphen rules based

on prefixing and recomposition. Whenever the user

makes a mistake, pops up an error message indicating

the wrong orthographic rule.

AmarganA (Yamato et al., 2017) is a game de-

signed for mobile phones and tablets that aim to prac-

tice orthography. Letters are shuffled, and the player

should change their position until the desired word is

correctly written. Grapphia (Assis et al., 2017) was

designed to aid students in spelling words that have

digraphs that correspond to the same sound. Sim-

ilarly, Na Ponta da L

´

ıngua (Gaspar et al., 2016) is

an open source tool that aims to help students ad-

dress this same problem in a ludic way letting stu-

dents play with the origin of words. Novel (Novais

et al., 2017) is an educational game to aid in the au-

tonomous learning of orthographic rules by improv-

ing the performance of students in social writing prac-

tices. Elements such as badges (medals or achieve-

ments), points, progress, and narrative are used to

make users feel motivated to perform tasks.

From related work, it is possible to observe that

JOE is a single initiative that focuses on accents and

hyphens. JOE differs as it incorporates a broader

range of hyphen rules and separates the training stage

from the game itself. Moreover, in JOE, the user hears

the word and should write it the right way, which

makes a different perspective for the game-play.

4 JOE: THE ORTHOGRAPHIC

GAME

JOE game was focused on supporting the changes

in rules of accentuation and hyphen introduced by

the new orthographic agreement. Such decision is

reasonable since these rules are considered the ones

that arise main doubts for general people. JOE sup-

ports general rules of accentuation, such as open diph-

thongs “

´

ei” and “

´

oi” and paroxytone homographs

(Ganho and McGovern, 2004). The accent and hy-

phen rules addressed by JOE are described in Table

1.

4.1 Architecture

The JOE architecture is based on MVC (Model, View,

and Controller layers). Each of these layers follows

some features and has distinct functions. The game

control actions are modeled by use case diagram of

Figure 1, which shows an overview of main features

that are present in JOE (training and playing).

UseCase Diagram0 2017/09/10 powered by Astah

uc

Player

Run Training Mode

Run Playing Mode

Show Hints

<<include>>

Figure 1: Use case diagram defining the actions of the user

through controller layer, simplifying the features that exist

in JOE.

The conceptual model, represented by the class di-

agram was described in the Unified Modeling Lan-

guage (UML) (Fowler, 2003). The model was devel-

oped incrementally and consolidated mode after the

fixation of the scope, of the rules and the comple-

tion of the experimental evaluation form, to ensure

that the implementation of the game follows what was

planned. Figure 2 shows the class diagram. The yel-

low classes match the Model layer. The blue ones

correspond to View layer, and the grays classes refer

to Controller layer.

The Model layer is composed of six classes high-

lighted in yellow. The Norm class models the general

types of rules (accent and hyphen). The Rule class

models a single orthographic rule. It has a keyword

to identify the rule, a description and its difficulty (for

player’s score). A Rule is composed of a set of hints

that are modeled by class HintRule. The HintRule

class contains a text that is displayed in Training mode

for each advanced word to help in learning the related

rules. The Word class models all the words of the

game, their audios, and their usage (common or un-

common). It has a rule identifier and related game

mode. The GameMode class presents two possible

ways to use the game: Play and Training. The His-

tory class stores the score and total hits to play and

the time spent by the user during the training mode.

The View layer has the game screens and is de-

scribed by the six classes in blue. They are designed

from XML files and loaded into classes that extend

the Activity class. They receive or send interactions

in components, changing values in their properties,

such as the sounds of words, messages, and effects.

The Controller class represents the Controller

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

434

Table 1: Accent and hyphen support for the new orthographic rules used in the game.

Keyword Rule

Juxtaposed

The hyphen is used on words composed per juxtaposition whose elements (nouns,

adjectives, verbs or numerals) constituting a syntagmatic or semantic unit and with own

accent, even if the first element is reduced.

Toponyms

The hyphen is used with compounds toponyms started by the adjective gr

˜

ao/gr

˜

a, or by a

verb, or when exists an article between its constituent elements.

Botanical and zoological The hyphen is used with compound words that designate species botanical and zoological.

Bem, mal, and vowel

The hyphen is employed in compounds formed by adverbs bem or mal (first element) and

any word beginning with a vowel.

Al

´

em, aqu

´

em, rec

´

em, and

sem

The hyphen is used in compounds with the elements al

´

em, aqu

´

em, rec

´

em, and sem.

Locutions The hyphen is not used with locutions of any kind.

Occasional and Historicals The hyphen is used in occasional vocabulary dazzle or the historical combinations.

´

ei and

´

oi

Open diphthongs

´

ei and

´

oi followed by vowel paroxytones lose the accent. Note: When

oxytone, these, along with

´

ei, remain with the accent, followed or not by ’s’.

’i’ and ’u’ on hiatus

The acute accent is used on the ’i’ and ’u’ tonics of oxytones or paroxytones if they are

hiatuses and are alone in the syllable or accompanied by ’s’. Note: When before ’nh’ or

after diphthong decreasing, they are not accented.

Paroxytones homographs The acute accent is used to differentiate a few pairs of paroxytones homographs.

Second element ’h’

The hyphen is used in prefixed or recomposed words whose second element is started by

’h’.

The shock of vowels

The hyphen is used if the first element ends with the same vowel that begins the second

element.

circum and pan

The hyphen is used if the prefix is circum or pan and the second element starting with a

vowel, ’h’, ’m’, and ’n’.

hiper, inter and super

The hyphen is used when the prefix is hyper, inter or super and the second element begins

with ’r’.

ex, sota, soto, vice, or vizo The hyphen is used when the prefix is ex, sota, soto, vice, or vizo.

p

´

os, pr

´

e, and pr

´

o The hyphen is used when the prefixes p

´

os, pr

´

e, and pr

´

o are tonics and graphically accented.

vowel + ’r’ or ’s’

The hyphen is not used when the prefix (or false prefix) ends in a vowel and the second

element begins with ’r’ or ’s’ and should be duplicated.

Elements with different

vowels

The hyphen is not used when the prefix (or false prefix) ends with a vowel and the second

element begins with a different vowel.

Enclisis and mesoclisis The hyphen is used in pronominal forms linked to the verb by enclisis or mesoclisis.

’co’ The hyphen is not used in ’co’ + word beginning with ”o”.

layer. It is responsible for mediating the data requests

to interact with the View providing the correct data

from the Model layer. It also has specialized methods

that perform the opening and sequencing of screens.

It is also responsible for controlling the storage of all

result data (either from training and playing) to be

shown at the end of each match.

4.2 Graphical Interface Design

Since the game was intended to be easy to use, attrac-

tive, and ludic for students, the interface was designed

before any View implementation in Android. The in-

terface was modeled using Mockups (Nguyen et al.,

2016) as shown in Figure 3. The game has three main

screens that interact with the player. The first con-

tains the game mode options with a summary of all

matches performed (number of hits, score, and time

played).

During mode selection, the main play screen is in-

voked with a set of words. Each word should be lis-

tened by the user, who has to spell it correctly. In

training mode, the user has a button, named verificar

palavra, which provides a hint message related to the

spelling rule for the listened word.

During playing mode, the screen has a countdown.

When the counter reaches zero or set of words is fully

explored, a result screen is displayed, showing the

elapsed time for the game, the number of correct an-

swers, and the number of errors of hyphen and ac-

centuation. This summary is important for players to

identify their performance. The game features three

screens that interact with the player. The initial one

contains the mode game options, plus a Historical set

of hits, the score and the time devoted to all matches

performed.

Orthographic Educational Game for Portuguese Language Countries

435

Figure 2: Class diagram of JOE. Classes in yellow, blue, and gray respectively corresponding to the Model, View, and

Controller layers.

Figure 3: JOE’s Interface design modeled using Balsamiq Mockups: (a) Home screen with choices for game mode. It also

contains hits, score, and time played in previous matches; (b) Play mode screen where questions need to be answered by user

during a fixed time. During training mode, the word check button displays a hint; (c) The result screen shows the number of

hits and misses in both hyphen and accentuation rules.

Figure 4: Game Screen: (a) Home; (b) Play Mode; (c) Help; (d) Results.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

436

4.3 Implementation Discussions

The game was built using Android Studio tool, and

the main features are depicted in Figure 4. The game

was developed using the API 8 (Android 2.2 Froyo)

to support a large number of devices. JOE is available

for free on Google Play Store. All the screens cor-

respond to classes derived from the Activity class. It

invokes the Controller to carry out interactions with

the database and to exchange parameters between

screens. Also, the screen orientation was set to por-

trait to avoid the problem of displaying items (misfits,

cut or outside problems). JOE requires portrait dis-

play, even if the user changes the device orientation.

The game information such as words and mes-

sages have been stored in the device via the SQLite li-

brary. This library allows for the creation of multiple

tables in a single file. Its memory consumption and

CPU requirements are adequate for mobile devices

that are not as powerful as conventional computers.

When JOE is opened, the vocabulary is loaded into

an SQLite database for faster queries. To populate

the tables for the game, we applied the xmlResour-

ceParser interface of the Android library. An XML

file was created with the filled attributes and accom-

plished a structure that while reading the file, the data

was properly loaded into database tables.

During the recording of audio for the quiz, we

found some difficulties on Google speech module

as it did not pronounce the new orthographic rules

correctly. Due to that, some words were sent to

Google module in a phonetically written style. Table

2 presents some examples of the recorded audio: their

correct writing (first recording), the resulting sound

from the first recording and it was written for the au-

dio corresponds the correct word.

5 EXPERIMENTAL EVALUATION

The experimental evaluation was designed using soft-

ware engineering experimentation approaches (Ju-

risto and Moreno, 2001). The experiment addresses

two central research questions: didactics and learn-

ing (Q1) and students’ impressions (Q2). It was

composed of experimental procedure and evaluation

form. The evaluation form contained 41 questions.

It collects the experience of users interactions with

the game, and their impressions related to usabil-

ity, ease of learning, and motivation to play again.

The last ten questions were for usability evaluation

(SUS (Albert and Tullis, 2013)). The evaluation form

was created using Google Forms. Some questions

were designed for quantitative analysis, whereas other

questions were designed to support the main results

through qualitative analysis.

The experiment was conducted in two days, with

62 volunteers (29 of high-school and 33 undergrad-

uate students). All volunteers were invited via the

Facebook social network. We measured students’ per-

formance prior and after using JOE. On Day 1, the ex-

periment was conducted with the students of the first

and second year of high-school and on the second day

with students from different periods of graduation in

Computer Science. JOE was assessed by running it on

an Android emulator, or by students in their own An-

droid devices (either by downloading the application

by PlayStore or by Bluetooth). Statistical analysis us-

ing all collected data was performed and implemented

in R (Lander, 2017).

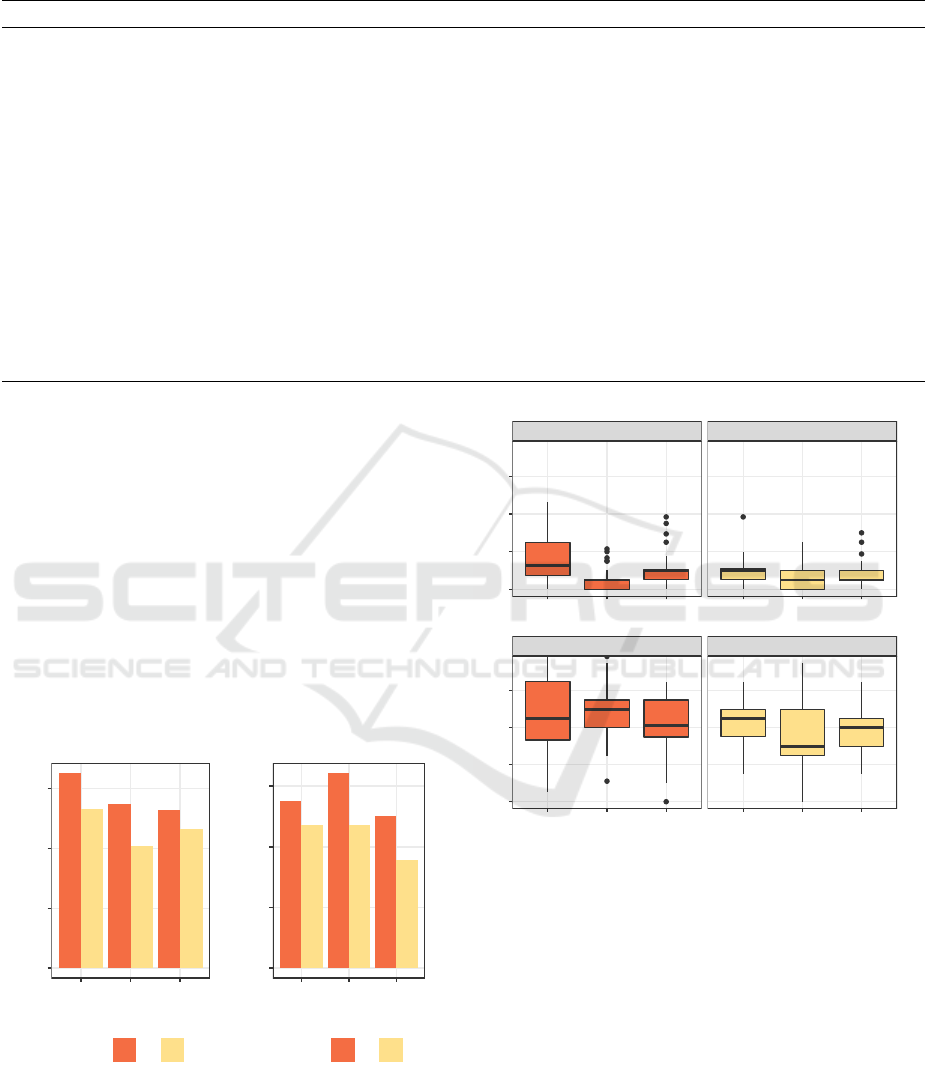

The first question (Q1) is related to the didactics

of JOE and student learning after training. Figure 5.a

presents the overall performance (percentage of er-

rors) of both high-school and undergraduate students

in spelling word with correct accent or hyphen. The

overall error is high (more than 50%) prior training.

This level of mistakes is an expected result since both

accentuation and hyphen rules presented in JOE are

considered difficult in Portuguese. In both cases, the

number of errors decreased after training. Relatively,

we observed a better improvement with high-school

students (from approximately 65% to 50%). This de-

crease can be explained by the time they spend during

training (Figure 5.b). They trained approximately five

minutes more than undergraduate students.

Figure 6 details the analysis presenting the distri-

bution of errors using box-plot separated by both ac-

cent and hyphen rules. It can be observed that the

number of errors using hyphen was much higher than

with accentuation. Also, considering the median er-

rors, the number of accentuation errors improved after

training. Such behavior is not apparent with hyphens.

Thus, we applied Wilcoxon rank sum test for both

hyphen and accentuation errors for all students com-

paring students’ performance prior and after training.

For accentuations, we observed a p-value of approxi-

mately 0.01, which refuted the null hypothesis of no

performance difference prior and after training. It was

possible to evidence an improvement of students in

the subject. However, for the hyphen, we got a p-

value of approximately 0.15, which did not refute the

null hypothesis (no significant difference) in hyphen

scenario.

To better clarify this result, we have deepened our

analysis by observing if students’ previous knowledge

on these subjected interfered with their performance.

Figure 7 depicts the relative number of errors prior,

during, and after training according to students’ pre-

Orthographic Educational Game for Portuguese Language Countries

437

Table 2: Recording of Audio.

Correct Writing Incorrect sound Phonetic correction

Coreia Cor

ˆ

eia Cor

´

eia

A fim de Afindi A fim d

ˆ

e

Abaixo de Abaixo di Abaixo d

ˆ

e

Acerca de Acerca di Acerca d

ˆ

e

Ao passo que Ao passo qui Ao passo qu

ˆ

e

Baiuca Baaiuc

´

a Bai

´

uca

Boiuno Booiun

ˆ

o Boi

´

uno

Circum-escolar Circ

´

um-escolar C

´

ırcum-escolar

Circum-hospitalar Circ

´

um-hospitalar C

´

ırcum-hospitalar

Circum-murado Circ

´

um-murado C

´

ırcum-murado

Cobra-capelo Cobra-cap

´

elo Cobra-capelo

Eletrossider

´

urgica El

ˆ

etrossiderurgica Eletrossider

´

urgica

Geo-hist

´

oria G

ˆ

eo-historia Geo-hist

´

oria

Micro-onda M

´

ıcro-onda Microonda

Para Par

ˆ

a P

´

ara

Sota-piloto Sota-pil

´

oto Sota-pil

ˆ

oto

Turma-piloto Turma-pil

´

oto Turma-pil

ˆ

oto

vious knowledge: none, hyphen only, accentuation

only, and both hyphen and accentuation. Students

who indicated an earlier knowledge only on hyphen

rules had worse performance. The students who re-

ported knowing both hyphen and accentuation had the

best performance before training, but they did not im-

prove after training. Finally, students who indicated

that they did not have previous knowledge of both hy-

phen and accentuation rules did not improve signif-

icantly after training. The result suggests that JOE

does not necessarily replace traditional teaching, but

it can be a great ally, especially for students who prac-

tice it more often, so that hints could be better ex-

plored.

0

20

40

60

prior training after

errors (%)

context

HS US

0

100

200

300

prior training after

time (sec)

context

HS US

Figure 5: Relative errors (a) and time spent (b) for high-

school (HS) and undergraduate (US) students reported by

rule knowledge on accentuation and hyphen prior, during,

and after training.

The second question (Q2) is related to students’

impression with JOE. The evaluation form contained

HS

US

prior training after prior training after

0

20

40

60

accent

errors (%)

HS

US

prior training after prior training after

0

20

40

60

hyphen

errors (%)

Figure 6: Box-plot of relative errors of both accentuation

and hyphen rules for high-school (HS) and undergraduate

(US) students reported prior, during, and after training.

two questions about the hints presented during train-

ing. The first one asked if the student found hints use-

ful and the second asked if hints were easy to compre-

hend: 82% and 77% of students, respectively, agreed

with these questions. Also, we asked if students were

motivated to use and if they learned using JOE. Again,

82% and 84% of students agreed with these ques-

tions. Figure 8 confirms such affirmations, as students

that indicated that playing JOE motivates to learn or-

thographic rules improved their number of errors af-

ter training. Also, students who registered that they

learned with JOE, apparently reduced their number of

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

438

errors after training.

We also applied a usability analysis using SUS

(Albert and Tullis, 2013). The SUS index obtained

by JOE was 79. Taking into account that it is a scale

of 0 to 100, where the closer to 100 better, this result

corresponds to good interface design (Bangor et al.,

2009).

0

20

40

60

80

prior training after

errors (%)

context

none hyphen accent accent and hyphen

Figure 7: Relative error performance according to the pre-

vious knowledge in either hyphen and accentuation rules.

Students who indicated that knew both hyphen and accen-

tuation rules presented the best performance before training.

Students who just meant to know accentuation showed the

best performance after training.

0

20

40

60

prior training after

errors (%)

motivated

no yes

0

20

40

60

prior training after

errors (%)

learned

no yes

Figure 8: Relative error performance of students prior, dur-

ing, and after training according to motivation and to learn-

ing benefits.

6 CONCLUSION

JOE is an educational game that focuses on learn-

ing/teaching accents and hyphen rules of the new Por-

tuguese orthographic agreement. The tool is avail-

able for free on Google Play Store. An experi-

ment with both high-school and undergraduate stu-

dents was conducted. From the experiments, we ob-

served that practicing Portuguese using a game-based

methodology is beneficial for students no matter their

grade level. We achieve more than 80% of students’

engagement to learn Portuguese with JOE. However,

further investigation is needed to attract the other 20%

of the student, who did not feel motivated to use JOE.

The game, although interesting, was considered

difficult by most students. Some difficulties found by

students were related to understanding the pronunci-

ation of words made by the game. The experience of

recording the audio for words showed this difficulty.

It was also observed that the students, after training,

had a higher hits rate on accentuation. We will study

the reasons for not achieving better performance on

hyphens. Particularly, if there is the need for the game

to tell students that they need to train more hyphen

rules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank CNPq, CAPES, and FAPERJ for

partially funding this research.

REFERENCES

Ackerlind, S. R. and Jones-Kellogg, R. (2011). Portuguese:

A Reference Manual. University of Texas Press,

Austin, bilingual edition.

Albert, W. and Tullis, T. (2013). Measuring the User Expe-

rience: Collecting, Analyzing, and Presenting Usabil-

ity Metrics. Morgan Kaufmann, Amsterdam, 2 edi-

tion.

Almeida, J., Santos, A., and Sim

˜

oes, A. (2010). Bigorna - A

toolkit for orthography migration challenges. In Pro-

ceedings of the 7th International Conference on Lan-

guage Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2010, pages

227–232.

Ara

´

ujo, N. M. S., Ribeiro, F. R., and Santos, S. F. d. (2012).

Educational games and responsiveness: playfulness,

reading comprehension and learning. Bakhtiniana:

Revista de Estudos do Discurso, 7(1):4–23.

Assis, L., Bodolay, A., Greg

´

orio, L., Santos, M., Vivas,

A., Pitangui, C., and Bandeira, D. (2017). Grap-

phia: Aplicativo para Dispositivos M

´

oveis para Aux-

iliar o Ensino da Ortografia. Anais dos Workshops

do Congresso Brasileiro de Inform

´

atica na Educac¸

˜

ao,

6(1):609.

Bangor, A., Kortum, P., and Miller, J. (2009). Determining

What Individual SUS Scores Mean: Adding an Adjec-

tive Rating Scale. J. Usability Studies, 4(3):114–123.

De Sousa Borges, S., Durelli, V., Reis, H., and Isotani, S.

(2014). A systematic mapping on gamification applied

to education. In Proceedings of the ACM Symposium

on Applied Computing, pages 216–222.

Orthographic Educational Game for Portuguese Language Countries

439

Diah, N., Ismail, M., Ahmad, S., and Syed Abdullah, S.

(2010). Jawi on Mobile devices with Jawi wordsearch

game application. In CSSR 2010 - 2010 International

Conference on Science and Social Research, pages

326–329.

Dom

´

ınguez, A., Saenz-De-Navarrete, J., De-Marcos, L.,

Fern

´

andez-Sanz, L., Pag

´

es, C., and Mart

´

ınez-Herr

´

aiz,

J.-J. (2013). Gamifying learning experiences: Practi-

cal implications and outcomes. Computers and Edu-

cation, 63:380–392.

Fowler, M. (2003). UML Distilled: A Brief Guide to

the Standard Object Modeling Language. Addison-

Wesley Professional, Boston, 3 edition.

Ganho, A. S. and McGovern, T. (2004). Using Portuguese:

A Guide to Contemporary Usage. Cambridge Univer-

sity Press, Cambridge ; New York, bilingual edition.

Garcez, P. M. (1993). Debating the 1990 Luso-Brazilian Or-

thographic Accord. In Working Papers in Educational

Linguistics, volume 9, pages 43–70.

Gaspar, W., Oliveira, E., and Cury, D. (2016). NaPon-

taDaL

´

ıngua: Um Aplicativo para Apoiar o Processo

de Ensino-Aprendizagem da L

´

ıngua Portuguesa.

Brazilian Symposium on Computers in Education,

27(1):60.

Juristo, N. and Moreno, A. M. (2001). Basics of Software

Engineering Experimentation. Springer, Englewood

Cliffs, N.J, 2001 edition.

Lander, J. P. (2017). R for Everyone: Advanced Analytics

and Graphics. Addison-Wesley Professional, Boston,

MA, 2 edition.

Leow, R. (2001). Attention, awareness, and foreign

language behavior. Language Learning, 51(PART

1):113–150.

´

Alvarez Valencia, J. (2016). Language views on so-

cial networking sites for language learning: the case

of Busuu. Computer Assisted Language Learning,

29(5):853–867.

Madeo, R. (2011). Brazilian sign language multimedia

hangman game: A prototype of an educational and

inclusive application. In ASSETS’11: Proceedings of

the 13th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference

on Computers and Accessibility, pages 311–312.

Marques, D. L. and Silva, A. P. S. (2012). OrtograFixe - Um

jogo para apoiar o ensino-aprendizagem das regras da

nova reforma ortogr

´

afica. In Anais dos Workshops

do Congresso Brasileiro de Inform

´

atica na Educac¸

˜

ao,

volume 1.

Munday, P. (2017). Duolingo. Gamified learning through

translation. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching,

pages 1–5.

Netto, D. P. d. S. and Santos, M. W. A. d. (2012). AlfaGame:

Um Jogo para aux

´

ılio no processo de alfabetizac¸

˜

ao.

In Brazilian Symposium on Computers in Education,

volume 23.

Nguyen, T.-D., Vanderdonckt, J., and Seffah, A. (2016).

Generative patterns for designing multiple user inter-

faces. In Proceedings - International Conference on

Mobile Software Engineering and Systems, MOBILE-

Soft 2016, pages 151–160.

Novais, I., Matos, P., Pereira, J., and Ramos, L. (2017).

Novel: Um Jogo Educativo para Aprendizagem de Or-

tografia. Anais do Workshop de Inform

´

atica na Es-

cola, 23(1):490.

Papastergiou, M. (2009). Digital game-based learning

in high school computer science education: Impact

on educational effectiveness and student motivation.

Computers & Education, 52(1):1–12.

Parejalora, A., Callemart

´

ınez, C., and Rodr

´

ıguezaranc

´

on, P.

(2016). New perspectives on teaching and working

with languages in the digital era. Researchpublish-

ing.net.

Santos, A. S. R. and others (2010). SoletrandoMob: Um

Jogo Educacional Voltado para o Ensino da Ortografia

na L

´

ıngua Portuguesa em Plataformas M

´

oveis. In

V Congresso Norte Nordeste de Pesquisa e Inovac¸

˜

ao

(CONNEPI), pages 1–8.

Yamato, E., Correa, A., and Martins, V. (2017). AmarganA:

A spelling game of the Portuguese language for use in

mobile devices. In Iberian Conference on Information

Systems and Technologies, CISTI.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

440