Autonomous Vehicles for Independent Living of Older Adults

Insights and Directions for a Cross-European Qualitative Study

Shane McLoughlin

1

, David Prendergast

2

and Brian Donnellan

1

1

LERO, School of Business, National University of Ireland Maynooth, Maynooth, Ireland

2

Intel Labs Europe, Intel Corp, Leixlip, Ireland

Keywords: Older Adults, Autonomous Vehicles, Driverless Cars, 65+, IT Adoption, User Experience, Business Models.

Abstract: Autonomous Vehicles (AV) are expected to have a revolutionary impact on future Society, forming an integral

component of future Smart Cities & regions. ‘Impacts’ range from changes in mobility, environment,

planning, infrastructure, employment, leisure time to disruptive business models etc. Designing user centred

mobility experiences for citizens ensuring trust, adoption and enhanced experience of emerging AV systems,

products and services is an important emerging research challenge today. It is projected that ‘older adults’

(65+) will encompass approximately one third of the mobility marketplace by 2060, with the broader ‘Silver

Economy’ set to provide enormous potential for new forms of product/services and related business models.

AV’s have the potential to prolong independent living of ‘older adults’ (OA) thus enhancing overall quality

of life. For example, driving cessation and mobility barriers correlate with poorer health outcomes. Ensuring

future AV adoption requires designing mobility experiences addressing the differing life contexts (i.e. health,

financial, mobility needs etc.) of OA. This paper presents context, motivation and initial findings from a

qualitative pilot study of Irish Older adults that informs the design of a cross-European study to support

‘Independent Living of Older adults’ in a future AV marketplace that encompasses new Mobility As A Service

offerings.

1 INTRODUCTION

Autonomous vehicle technologies are expected to

lead to a disruptive and eventually transformative

change on mobility in society over the next 30 years,

allowing humans to move away from manual control

of vehicles to supervisory control and eventually no

control. This transformation is anticipated to include;

a reduction in transport related accidents, a freeing up

of driving time for other in-vehicle pursuits, changes

to traffic congestion and road infrastructure, new

business models of vehicle ownership/mobility,

evolving insurance models, changes to vehicle

driving licencing, new modes for delivery of goods

and services, new mobility opportunities for the

disadvantaged and disruptive changes to the

workforce. In essence, the transformative change on

mobility will have a larger lasting transformative

change on society overall, with humans mental

models of the car and mobility shifting in the coming

years and AV systems and services envisaged as

forming a core component of ‘Smart Cities’ and

‘Smart Regions’ of the future. The key research

challenge will be ensuring that AV technology will

ultimately have positive consequences for the human

condition overall, i.e. improving quality of life for all

citizens. Thus, creating ‘inclusive’ or ‘human’ ‘Smart

City’ and regions requires integrating AV systems

and services which consider differing and complex

citizen needs and preferences.

One segment of the human population seen as

potentially benefiting the most from AV technologies

are older adults. In this respect, older drivers are said

to represent ‘an innovation paradox when purchasing

vehicles’ (Yang & Coughlin 2014). New advanced

vehicle technologies first become available in

relatively expensive vehicles whereby it is often older

adults who have the resources to purchase them.

Thus, older drivers can be seen as a critical test

market for new automotive technologies. However,

whilst older and disabled people are portrayed as lead

use case for the development of the partial and fully

autonomous vehicles, OA are seldom early adopters

of new technology and are the market segment most

sceptical about dependability and surrendering

control to a full autonomous system. For example, a

294

McLoughlin, S., Prendergast, D. and Donnellan, B.

Autonomous Vehicles for Independent Living of Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0006777402940303

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2018), pages 294-303

ISBN: 978-989-758-292-9

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

recent MIT related online survey of US adults (N =

2094) found older adults have the lowest propensity

to adopt fully autonomous vehicles (Abraham et al.

2016). Importantly, the number of fatalities per

million miles travelled increases the older we get

(IIHS 2016). There is a proven close correlation

between Driving Cessation and poorer health

outcomes, and the risks of clinical depression doubles

once an older adult surrenders their driving licence

(Chihuri et al. 2016). In Europe, EU-28 will see a

doubling of those aged 80+ from contemporary levels

of 5.3% to 10.9% by 2050 (Eurostat 2015).

Cumulatively, it is projected that ‘older adults’ (65+)

will encompass approx. 1/3 of the mobility

marketplace by 2060 (Harbers & Achterberg 2012).

In sum, given the unique health, behaviours and

technological ability of OA etc., “the successful

design, implementation, and marketing of these

technologies will require special consideration of the

unique needs, attitudes, and capabilities of older

drivers” (Eby et al. 2015). How can we build trust and

encourage older people to become lead users of AV?

This paper presents initial findings from an

exploratory pilot study on suburban and rural ‘Older

Adults’ in Ireland, to inform the research direction

and design of a cross-European qualitative study on

‘Older adults’. The initial guiding research question

is as follows: How can AV systems and services

support independent living of Older Adults in the

advancing Silver economy? The paper is structured as

follows: We begin by presenting the context and

motivation for this study based on a scoping review

of the literature. Next, we present our method chosen

followed by the findings section overviewing our

participant’s unique contexts and presentation of

thematic areas and themes emerging from analysis.

We then discuss findings according to the five

interrelated work streams identified and conclude by

highlight relevance of findings to existing prominent

technology adoption models as well as outlining the

next steps in the research project.

2 CONTEXT & MOTIVATION

According to Strategy Analytics, Level 4 high

automation will grow to 42% by mid Century

(Strategy Analytics 2017). L1-3 systems offer

opportunities prolong driving and L4 & 5 systems

may help promote and lower the costs of independent

living and solve many of the mobility and social

loneliness issues associated with ageing. From a

market perspective, the ‘silver economy’ is set to

grow rapidly. Europeans over 65 already have a

spending capacity of over €3 Trillion and the number

of citizens with age related impairments will reach 84

million by 2020 (Iakovidis 2015). The needs and

spending power of this market segment will greatly

expand as Europe moves from 4 working age people

per older adult to 2 by 2060 (Eurostat 2015).

Existing evidence on the unique mobility

challenges of older adults encompasses key factors

such as location, living arrangements, health

characteristics, Tech Literacy and gender etc. AV

systems present unique opportunities to address each

of these factors thereby improving QoL for older

adults (by increasing active and independent living),

as well as unique challenges in designing AV

mobility systems and mobility services that cater for

OA particular needs.

In Europe 29% of ‘older adults’ live alone, with

higher proportions of OA living in rural and isolated

areas and a higher proportion of OA living alone in

urban areas (Holley-moore & Creighton 2015). This

is despite the reality that sufficient public transport

offerings are lacking in rural compared to urban areas

(Holley-moore & Creighton 2015). For example, in

the USA, older adults’ reliance on automobility

increases with age in part due to ‘last mile’ mobility

deficits and ‘arm to arm’ care requirements. In

Ireland, rural public transport options have declined

due to reduced population density in rural regions

caused by out-migration of younger adults to urban

areas. This is despite the reality that in Ireland alone

38% of the population are classed as ‘rural’ according

to the most recent national census (Connolly et al.

2011). Furthermore, half of the world’s population

reside in rural areas (Westlund & Kobayashi 2013)

and this is similarly the case in Europe (EU, 2015).

Older adults have unique health characteristics

compared to younger age cohorts resulting in

differing driving patterns and behaviours, the

reduction and cessation of driving, and the ability to

access and utilise adequate transport options. Studies

show OA’s in general have slower reaction times,

decreased flexibility and co-ordination with

significant reductions in strength and muscle mass

(Eby et al., 2015). Collectively, these characteristics

mean OA’s tend to have difficulty entering and

exiting vehicles, difficulty driving for prolonged

periods and engaging in certain driving behaviours.

Furthermore, as age increases so too does; the

proportion of adults with physical and cognitive

disabilities the proportion of adults with multiple

disabilities and the proportion of adults with health

conditions requiring hospital & doctor visits and

medications. In the US, 39% of those aged 65+ suffer

with one or more disabilities ranging from, Hearing,

Autonomous Vehicles for Independent Living of Older Adults

295

Vision, Cognitive, Ambulatory to the ability to self-

care and live independently (Wan, He; Larsen 2014)

whilst 44% of 65+ Europeans report one or more

disabilities, reaching 60% for those aged 75+ . In this

respect, declines in health characteristics are a leading

cause of driver cessation, despite a well-documented

association between driving cessation and declines in

well-being and other important health measures

(Chihuri et al. 2016). Aside from the vicious cycle of

health and driving cessation outcomes, health as a

differentiator of OA from younger cohorts leads to

unique challenges in designing AV product services

that can be adopted by OA, and designed with OA

needs in mind. The higher prevalence of disabilities

presents challenges of ‘door to door’ or ‘arm to arm’

assistance, as well as the design of in-vehicle systems

that cater for OA needs where one or more disabilities

are present etc.

Research has found that the majority of trips taken

by OA are for shopping, family visits, recreation,

social engagements as well as medical related

journeys (Duncan et al. 2015), with discretionary

travel most limited by circumstances of aging.

Currently health and other factors means OA driving

behaviours and patterns tend to differ to younger

adults. OA tend to self-regulate their driving, avoid

travelling at busy times, alter their travel routes and

decrease their journey times (Shergold et al. 2015).

Thus, OA mobility is constrained even for those who

still drive.

Furthermore, access & use of in-vehicle

technologies differ to younger users. Older adults are

more likely to have difficulty using advanced in-

vehicle systems, taking longer to learn these systems,

and to misunderstand in-vehicle technologies purpose

and full capabilities (Eby et al. 2015; Shaw et al.

2010). Some studies suggest older adults do show

willingness to adopt some ADAS systems (Souders &

Charness 2016). Although older adults may not be

adverse to learning new technology granted they are

informed of their benefit (Yang & Coughlin 2014) it

is well established that learning new skills and

changing routines is more difficult (Craik et al. 1996).

Older adults also tend to have less technological

ability and understanding of features. Furthermore,

some studies have suggested older adults learn to use

these systems differently, relying more on vehicle

manuals, car-salesmen and less on trial-and-error to

younger drivers (Eby et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2010).

Finally, gender has arisen as a significant variable

in the literature with women more likely to expect to

cease driving due to aging and men with Mild

Cognitive Impairment less likely to cease driving than

women. Prior research also suggest ‘Trust’ towards

technology differ by OA gender, with females more

wary of technological advancements (Shergold et al.

2015).

Given the insights presented above, surprisingly

little research on the potential for adoption of assisted

and autonomous vehicles and AV design

requirements has occurred for this important

demographic. Recent studies have identified a gap in

our understanding of Older Adults and the design of

future AV systems including In-vehicle Communica-

tion Systems (IVCS) and In-Vehicle Human

Computer Interface (IVHCI). For example, according

to Young et al

(2017)

, a comprehensive review of

automotive HMI design guidelines (from 2000 to

2015) revealed guidelines do not address design

issues related to older driver impairments .

Thus, the aim of this project will be to contribute

to this knowledge gap and deliver ethnographic, User

Experience and market insights about how the needs

and behaviours of drivers in different geographies

change through the later life course and how best AV

systems and services can cater for this important

demographic.

3 METHOD

A qualitative research approach was chosen to

explore the main research question. Qualitative

methods can be particularly valuable in such cases

where a research topic is new and little understood, as

is the case with ‘Older adults’ and ‘AV’.

Furthermore, qualitative methods better ensure

capturing the rich context of a phenomena, by using

techniques designed to allow participants freedom to

impart experience and evidence in their own words,

language, circumstances and surrounding context.

This allows for unforeseen themes and insights to be

generated not possible in positivist studies. For

example, the initial scoping review found disabilities

amongst older adults and health issues pose

significant challenges for driving and mobility. The

pilot stage allows us to understand health and

disabilities in greater detail such as how it affects

respondents’ current mobility scenarios.

The method chosen for this initial stage of the

study was the ‘open ended in-depth interview’ to

explore the context of older adults in relation to

current and future mobility requirements and their

surrounding life context. An interview schedule was

designed to generate themes surrounding such aspects

as lifestyle, health, mobility needs and mobility

experience etc. Theories of technology adoption were

reviewed (i.e. UTAUT

2 and TAM3 (Venkatesh &

SMARTGREENS 2018 - 7th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

296

Bala 2008; Venkatesh et al. 2016)) and questions

reflected core concepts including Habit, Hedonic

Motivation and External Variables etc. (Ghazizadeh

et al. 2012). The pilot stage serves the purpose of

generating insights and themes to inform the design

of the main study and its objectives. Pilot Interview

questions were designed to explore the thematic

areas: a. Participant Profile and Lifestyle b. Driving

status & history c. Driving/Passenger experience d.

Public Transport/ride-sharing e. Health & Aging f.

Technology g. Vehicle technology. Examples of

questions included; a) “If you have ceased or reduced

driving, could you tell me about the circumstances

and/or decisions that led to stopping/reducing

driving?” b) “Can you talk about a recent experience

as a passenger, and how it felt?.” C. “What is the

most pleasurable thing about driving?”

Interview question responses were aided with

additional prompts to ensure consistency amongst

respondents. The ‘critical incident technique’ was

employed to aid recall and encourage story telling.

Recruitment of participants was through third party

community organisations, and interviews took place

in rural and suburban environments in September

2016. Ten older adults were recruited for the pilot

study based on availability and variation, whereby

variation in participants included; age, gender,

marital status, location, driving status, disability,

living arrangements etc. Interviews typically lasted

from 1 ¼ to 1 ½ hours, and were subsequently

transcribed and inductively thematically analysed

using MaxQDA software. The pilot captured data

according to four categories 1) active drivers 2) self-

limiting drivers 3) older adults who have ceased

driving, and 4) older people who have never driven.

The sample ages ranged between 68 and 91 (M =

78) with 6 males and 4 females. There were 7 married,

2 widows and 1 widower. 5 participants resided in

rural areas whilst 5 resided in a suburban town or

village. 2 of the respondents lived alone, with 8 of the

respondents having one or more disabilities covering

visual, cognitive, hearing, speech, ambulatory, self-

care and independent living etc. Three of the

respondents currently drive, whilst 3 reported driving

reduction, 2 had ceased driving and 2 had never

driven on public roads.

4 FINDINGS

We begin by providing a brief profile of each

participant to sensitise the unique contexts of OAs’,

followed by presentation of initial thematic areas and

themes emerging from pilots conducted. An ‘audit

trail’ is provided for transparency by presenting some

examples of participant responses corresponding to

themes generated.

4.1 Profiles

Pauric is a former school teacher and lives alone in a

rural bungalow. He is a widower with two children.

He has regular contact with his children and

grandchildren as well as his brother who he holidays

with. Pauric likes driving, and drives a recent (2016)

vehicle with the latest ADAS features. Living in a

rural area, Pauric relies heavily on his car. The nearest

train and bus stations are not accessible by walking.

Pauric has hearing difficulties and lower back

problems for which he uses a ‘back roll’ in the driver

seat for relief.

James is a retired bus/lorry driver living in a

suburban area. James has three daughters whom he

regularly drives for. He lives with his wife and ‘likes

to keep busy’ which includes driving for his family

and a ‘meals on wheels’ scheme. James likes driving

and describes it as a, ‘hobby in a way’. He drives a

2008 saloon diesel car. James endures a studder and

some back problems.

Peter is also a retired bus/lorry driver living in a

suburban area. He lives with his wife and recently

divorced son. Peter often drives his wife as well as

sometimes driving his sister who has MS. Peter drives

a 2011 small size 1l petrol car. He has become less

active overall due to health episodes up until last year.

Tommy is a retired airport worker and is married

with his second wife. He has 8 children and 23

grandchildren. Tommy lives in a rural area, and has

reduced his driving to occasional short journeys. He

is losing his eyesight in his left eye, and his hearing is

poor. He lost his hearing aids and struggles with the

1000 euro cost of getting new ones. Tommy drives a

small 2014 petrol car. Most of Tommy’s transport is

via his children, the community (Third Age) bus

scheme, and occasionally his wife. The nearest public

transport is 2 miles away in the nearest town.

Orla lives with her husband in a suburban semi-

detached house, along with her son. Orla developed

Parkinson’s disease and has reduced driving as a

result. She hides her illness in the community as is

afraid of ‘stigma’. Orla finds reversing difficult as her

‘neck is not great’. She notices her husband’s

concentration is not as good as it used to be on the

road. Orla relies on her husband and public transport

for most of her mobility.

Cara is a farmer in rural Ireland. She lives with her

husband and daughter and has 6 children. Cara is

afraid of driving on public roads. Her ‘nervousness’

Autonomous Vehicles for Independent Living of Older Adults

297

about driving has increased as she has aged. She relies

on her children and taxi’s for transport, as her

husband stopped driving 2 years ago. As she lives

over 10km from the nearest town, taxis are expensive.

She describes herself as a passenger driver,

particularly as a result of monitoring her husband

driving as his health failed. Cara is in good health.

Gene has 3 children and lives with her son in a

rural area. She is widowed, and was previously a

nurse. Gene had done all the driving due to her

husband having an accident in the late 80s. He died

approx. 5 years ago. She had to give up driving due

to deteriorating health, and greatly misses driving, as

she is isolated as a result. Gene suffers with

Glaucoma. She also experiences arthritis, resulting in

tactile issues. She requires frequent toilet breaks due

to incontinence. She relies on a combination of her

son, taxis and the goodwill of others for lifts.

Nora lives in a private nursing home because of

significant health issues. Nora is wheelchair bound

after suffering a series of health events including

kidney problems that left her on dialysis for a period.

She has 3 children, one who lives in Ireland as a taxi

driver. Nora has never driven due to nervousness, and

eventually poor health. She is widowed, and

experiences money problems, as her available income

is spent on nursing home arrangements. She relies on

her son for transport. She also suffers agoraphobia

and arthritis and has tactile issues with her hands.

Nora feels isolated and spends her days in the

smoking room on her own in the nursing home.

Sam gave up driving two years ago due to

deteriorating health. He drove all his life for his job

as he ran his own ‘Plant Hire’ business. He lives at

home in a rural area with his wife and daughter and

relies on his children and taxi’s for transport. Sam still

feels he can drive, and is aggrieved that his doctor did

not sign off on a renewal of his driving licence. Sam

has arthritis in his arms, legs and neck. He is on a lot

of medication that leaves him confused and

disoriented at times. He suffers poor hearing and

vision, and his verbal speech is poor at times. Sam

experiences some memory problems and requires

frequent bathroom breaks. He requires help putting

on in seat belt. His travel is reduced to essential travel

only (e.g. medical appointments) due to availability

of his children and costs of taxis.

Cathal is a retired police officer and lives in a

suburban area with his wife. He has drastically

reduced his driving due to a cancer diagnosis five

years ago. He relies on his wife and public transport

for mobility needs. They have a 2004 hatchback

model. Cathal does not miss driving because he is no

longer comfortable doing so. His main health issues

now is lingering cancer in the urinary area. He has a

uretic catheter bag attached for urine. Con says he can

read without glasses but used to have glasses for

driving.

4.2 Themes

4.2.1 Mobility and Family

The older adults we spoke to in most cases had an

interdependent relationship with their family when it

came to mobility. Thus, mobility was an important

space and rationale for social interaction with family

from spouses, siblings, children, to grandchildren.

Whereas most participants who reduced/creased

driving or had never drove were reliant on their

children for transport needs, those who drove were

often called upon by siblings, or children to drive. For

example, John has a daughter with sight difficulties

so he ‘has to drive her around here and there' as well

as the grandchildren. This resulted in OA having a

needed ‘role’ or ‘purpose’ in the family for those who

drove, whereby for those who did not drive the car

was a space for social interaction with their family.

4.2.2 Health & Aging

Through the course of the interviews, participants

talked about their health, from difficulties and

disabilities to short and long term medical conditions.

Responses were elicited on a range of physical and

cognitive disabilities that older adults experienced

ranging from ‘eyesight’, ‘speech’, ‘cognitive’,

‘fragility’, ‘tactility’, ‘Incontinence’, ‘hearing’,

‘ambulatory’ and ‘medication’ etc. For example, Sam

spoke about a number of medications he is on which

affected his lucidity, memory and concentration

depending on the time of day or other factors. Orla,

Nora and Gene lives with arthritis that affected their

mobility and tactility. Gene and Tommy had severe

sight difficulties affecting their mobility and

awareness. Sam and James had speech problems

inhibiting communication. Several respondents also

had hearing difficulty. For example, according to

Pauric, ‘it is a bit of a burden, people in the back

assume I can hear what they are saying but I don't…

looking at people makes it easier’. For some, health

issues affected where they needed to sit in the vehicle

i.e. ‘seat preference’. As such, according to Nora, ‘I

like to a front seat passenger, I can't sit in the back

because of travel sickness, even short journeys',

whilst Gene responded that, ‘'it always has to be the

front seat if I can because you have more space for

my legs underneath’.

SMARTGREENS 2018 - 7th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

298

4.2.3 Impact of Not/Reduced/Ceased

Driving

Whereas almost all the suburban respondents we

interviewed referred to at least some availability of

public transport alternatives, as well as community

organisation alternatives (e.g. Third Age Foundation

minibus), rural participants mobility was impacted

the most whereby public transport options were

limited to taxi services with associated costs

involved. For example; Cara remarked, ‘There are

places I want to go that I can’t go and I have to leave

it for another week and another week and so delayed

circumstances getting things done.., I can’t go when I

want to go when I decide I’m going’ (Cara), whilst

Gene said‘it impedes people not only me and confines

them to their homes and increases mental distress’

(Gene)

4.2.4 Technology

Only half of the respondents used the internet. Non-

users cited, ‘a lack of interest’, lack of ‘digital

literacy’, ‘cognitive impairments’ such as memory

problems, ‘eyesight’, and ‘tactility’ issues due to

arthritis. Whilst 4 of the respondents had a

smartphone, just two used the internet on their

smartphone. As several of the respondents suffered

arthritis, this caused tactile problems that became a

barrier for some in using even basic features of a

phone. For example, according to Gene, 'The buttons

are bigger, and if I get a text message… I keep having

to press it to get the text message, I wouldn't be able

to text back… with my fingers’

4.2.5 Changed Driving Behaviours

Changed driving behaviour themes which emerged

were increased ‘tiredness’, ‘cautiousness’,

‘concentration’ and ‘distraction’, as well as reduced

‘speed’ and tolerance for ‘motorway’. For example,

Pauric’s response echoed the sentiment of several

participants we spoke to; ‘I seen my daughter and my

son there and I'd say you are going too fast but they

probably aren't, so more caution would be one thing,

you have to keep alert and watch more because you

can lose your focus '. Such themes highlighted aging

and driving experience results in differing

perceptions and attitudes towards driving by OA.

Furthermore, the need to stick to ‘familiar roads’,

avoid ‘night time’ driving and certain ‘times of the

day’ also emerged confirming findings from prior

studies (Shergold et al. 2015).

4.2.6 Pleasant Journey

Several questions were posed to elicit what

participants consider a good driving/passenger

experience. We posed the questions, ‘What is the

most pleasurable and frustrating thing on a journey’,

‘What makes you more nervous and less nervous as a

driver/passenger’ and ‘Can you describe what you

consider an ideal or pleasant experience driving?’

The most frequent responses for a pleasant or

pleasurable drive were ‘good road conditions’,

‘music’, ‘Scenery’, ‘breaks on long journeys’, the

‘destination’ and ‘good drivers’ (which for one

participant meant, ‘decisive drivers’).

In terms of what makes respondents ‘frustrated’

or ‘more nervous’ on journeys, the most common

responses referred to ‘perceived speed’, the driving

behaviour of ‘other road users’ and ‘bad traffic’.

Some responses referred to ‘perceived speed’ in terms

of driving too slow and not being ‘assertive’ on the

road. For example, according to Gene, ‘I don't like

somebody driving too slow, that annoys me because I

didn't drive like that’. For other respondents what

makes them frustrated or nervous was driving too

fast, such as for Nora, ‘to me if they are going fast

they are going fast, I don't look at the speedometer I

just say [person] you are going too fast’. What

emerged from respondent interviews was the

perception of speed had changed for several of the

respondents. What they considered fast when they

were younger had changed as they aged. For example,

according to Cathal, ‘as you get older you don't have

the same, the speed of the other car is the speed that

confuses most I think'.

In terms of ‘other road users’, whilst some

responses referred to obeying the rules of driving

such as obeying road signs and correctly using

roundabouts, other responses referred to what they

considered good driving etiquette or conscientious-

ness of other road users. For Cara, this meant not

‘hogging the roads, and not making any effort to

move in and let other passengers by for miles and

miles, that’s frustrating’. Gene remarked, ‘people

who blow horns behind you, that annoys me', whilst

James referred to drivers weaving between lanes,

where ‘common courtesy doesn't exist'. Overall,

respondents reported that as passengers, what made

them less nervous was the ‘assertiveness’, the

‘steadiness’, the ‘awareness’ and the ‘patience’ of the

driver. Examples of the aforementioned themes are as

follows:“when the person who is driving is confident

when he goes to move” (Cathal) “I like a steady

driver with no jerks” (Pauric) “To drive easy and not

to push.” (James) Over the course of the interview, it

Autonomous Vehicles for Independent Living of Older Adults

299

should be noted that many of the respondents had

strong views on driving etiquette and the driving

behaviour of other road users.

4.2.7 Passenger Activities

As passengers, the most significant themes to emerge

were in terms of observing ‘scenery’, ‘having

conversation’ and ‘watching the road’. Cara likes to

look at the scenery, houses, landscape whilst

travelling. She is interested in understanding who is

living where, what land is being used for, and things

she has not spotted before. She will also talk on the

journey and make conversation. Whilst Pat likes to

'see what happens along the line, what changes are

being made as you go along, when you driving a car

you never get that view... I like that' (Pat). The

participants we spoke to (both when referring to

private vehicles and public transport (like buses and

trains)) in almost all cases emphasised the activity of

observing and looking around on journeys as well as

conversation, rather than activities such as reading,

browsing etc. For example, according to John when

referring to public transport, 'there is no such thing as

conversation anymore because everyone has their

earpieces in or are texting’. Instead, several of the

participants placed emphasis on observing changes to

the landscape and buildings, and recalling and

associating memories to places they observed.

4.2.8 Passenger Drivers

In terms of ‘watching the road’, most of the

participants we spoke to could be considered

‘passenger drivers’. For example, James noted, 'I am a

driver all the time' even though he is only a passenger,

‘I take note of what people are doing, isn't that what

you do!', Gene believes, 'as a passenger you have a

different perception of things than a driver', whilst Orla

remarked, ‘Nowadays I don’t sleep, I just keep my eye

on the driver’. When asked to talk, ‘about your

experience being a passenger in a car transport?’,

respondents referred to the ‘deteriorating health’ or

‘concentration’ of their spouse, their own ‘prior driving

experience/history’, and the need for a ‘sense of

control’ in reasoning why they watch the road and alert

the drivers to potential dangers/hazards. In terms of

‘sense of control’, several passengers engage in

‘passenger driving’ to relieve anxiety and maintain a

sense of control of their safety and the driver.

4.2.9 Public Transport and Ridesharing

Participants’ motivation to use public transport like

buses and trains referred to ‘convenience’, ‘Traffic’,

‘Cost’, ‘Parking’ and ‘lack of alternatives’. In terms

of ‘Parking’ and ‘Cost’, examples include, ‘the car is

a liability in town, you have to find parking and pay

for parking, sometimes very highly'. Convenience

was cited for some in terms of close and frequent

availability of options, for example, ‘we are lucky

enough here…there are eight buses leaving every day

and eight buses back' (Cathal). ‘Traffic’ was cited by

several participants for those who still drove, in terms

of the ‘the flow of traffic and busy streets’ in the city.

Finally, some participants referred to ‘lack of

alternatives’ such as for Cara who took a taxi to catch

a train into the city when her sons and daughters

weren’t available. In terms of taxi’s and taxi ride-

sharing, most participants showed reluctance or

avoidance citing, ‘trust’, ‘cost’, ‘Lack of need’ or

‘lack of alternatives’. In terms of ‘trust’, whilst some

showed an aversion to taxi’s altogether such as for

James, ‘I've heard from alot of people over the years

that a taxi man will bring you around and go the long

way' (James), others referred to their use in short city

trips only; 'I wouldn't get in to it for a long journey…

I would be very wary of taking a taxi out from Dublin

to where I live with a stranger, I would not be

comfortable enough… I wouldn't even be aware if

they are on drugs or not.' (Gene). Whilst Cara and

Orla limited taxis mainly to drivers they knew. For

example, Orla replied she would feel uncomfortable

getting into a taxi with a male driver who she does not

know. Reluctance was also shown for taxi ridesharing

in terms of lack of ‘trust’ in sharing with strangers.

According to Tommy, ‘there’s always a maniac who

wants to put his hand in your pocket’. Finally, some

participants cited a ‘lack of need’ due to alternative

transport options, whilst the ‘cost’ of taxis was raised

for some living in rural areas.

5 DISCUSSION

Initial analysis of pilot data led to 5 proposed

interrelated work streams. (1) Impact of AV's on

Independent Living (2) Adoption factors for AV (3)

In-Vehicle design requirements (4) Mobility As a

Service Capabilities (5) MaaS Business Models for

OA. Initial findings from thematic analysis in relation

to each work-stream are presented as follows:

5.1 Impact of AV’s on Independent

Living

Findings suggest that the greatest positive impact on

Independent Living of Older Adults may be for rural

citizens, whereby AV’s may increase social

SMARTGREENS 2018 - 7th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

300

interaction, ability to travel and reduce isolation for

this cohort. Irish rural citizens we spoke to are

constrained by reductions in available public

transport options, with the ‘cost’ of taxi’s and issues

of ‘trust’ an inhibitor for more frequent travel.

However, currently ‘ride sharing’ is not a norm for

rural citizens we interviewed due to unfamiliarity

with the concept as well as issues of ‘trust’. As it is

expected that future AV service models will emphasis

ride-sharing due to cost, whilst ‘country-road’ driving

poses challenges for AV design, this requires further

research attention.

Findings suggest that we do not yet know what

the net consequences for social interaction with

family members for older adults will be as we

transition to autonomous vehicles. Currently an

interdependent relationship with family exists around

mobility for OA. Whether AV’s lead to increased

mobility for Older Adults that increases overall

family interactions/engagement or results in the

further breakdown of family ties is a pertinent

research question looking forward.

Consistent with prior work linking driving

cessation with poorer health outcomes (e.g.

Depression, declining physical health etc.), a key

reason participants we interviewed ceased driving

was due to declining health. However, some

longitudinal studies tracking ‘Older Adults’ health

before and after driving cessation (e.g. Edwards,

Lunsman, Perkins, Rebok, & Roth, 2009) have found

steep declines in health after cessation. Furthermore,

a recent study suggests that increased cognitive

decline is shown after driving cessation (Choi et al.

2014). Given the practice of driving for elderly people

innately requires the practice of Cognitive Control,

from concentration, memory, peripheral awareness,

reasoning, decision making etc., the transition to

autonomous driving for this cohort could potentially

have ramifications for aspects of cognitive health of

‘Older adults’ unless counterbalanced through other

activities. A research challenge will be to understand

how the transition to AV’s influences OA overall

health, and whether in-vehicle activities can be

designed to compensate.

5.2 Adoption Factors for AV

What emerged through the pilot findings was that the

older adult cohort’s willingness to adopt AV’s may

well go beyond the reported safety of AV vehicles

and extend to perceived/observed driving etiquette

and behaviours of AV on the road. Thus,

‘Performance Expectancy’ measures should reflect

such aspects. Whilst driving etiquette may relate to

AV ‘courteousness’ to other road users, for example

heavy vehicles and slow driving vehicles pulling in to

let other vehicles pass or to warn other vehicles about

hazards ahead, driving behaviours could also relate to

conscientiousness to older adult’s ‘cautiousness’,

‘perception of speed’ or their ‘fragility’ relative to

younger drivers. Furthermore, many of the OA we

spoke with had strong views on what they perceived

as ‘good driving’ and ‘bad driving’, referring to some

drivers ‘rushing’, ‘weaving between lanes’, ‘breaking

tightly’ etc. Naturally, as AV’s begin to appear on

roads in the future, such views will translate across to

how OA view AV driving. As AV’s will be capable

of multiple driving behaviours/styles depending on

user demands, the challenge will be linking OA

perception of how the AV drives back to the user of

the vehicle.

5.3 In-Vehicle Design Requirements

Findings suggest that focusing on health and location

rather than age provides a better lens to understand

OA and mobility. The unique requirements of OA in

terms of health issues/conditions including

medications have consequences for the design of the

AV’S particularly IVCS and IVHCI. Separate or

combined participant disabilities/conditions acted to

limit one or more activities of making a journey, from

using satellite navigation, to hands free voice, to

memory problems related to the route, purpose or

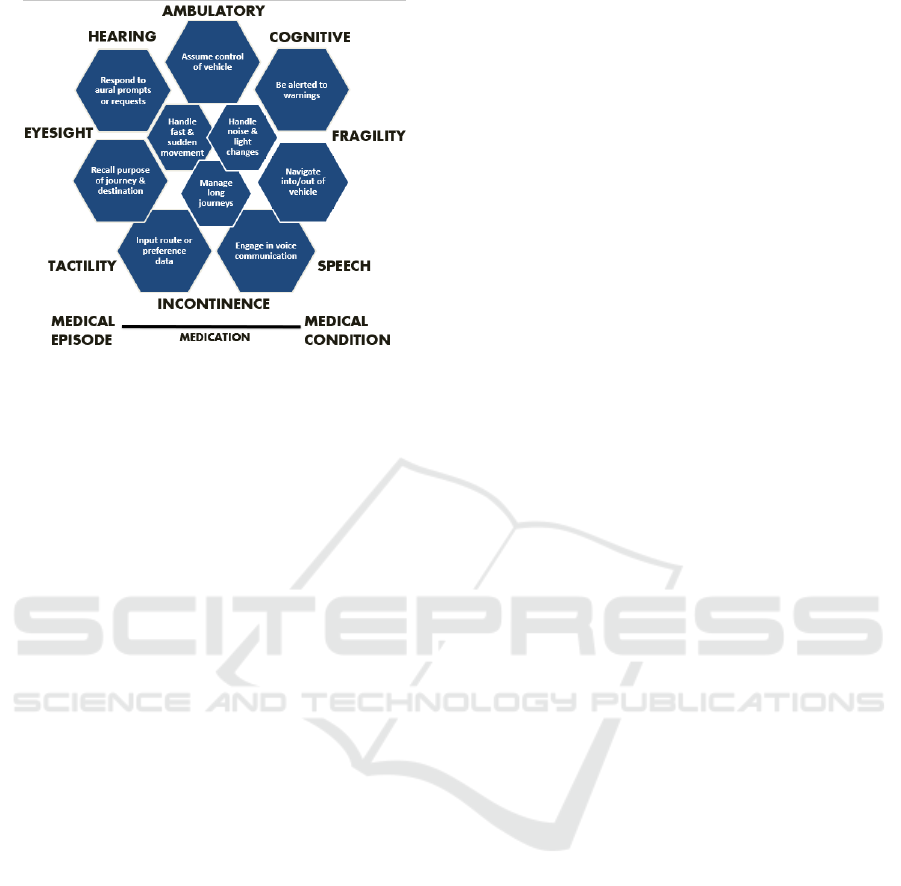

distribution of a journey. Figure 1. below outlines the

health themes emerging and shows how one or more

of these themes have one or more consequences for

OA ability to adopt and use an AV. For example,

‘Incontinence’ suffered by several participants meant

they were unable to ‘manage long journeys’, without

requiring frequent toilet breaks, whilst ‘cognitive’

impairment could mean a passenger forgets the

purpose of the journey or is unclear where they have

arrived and why. How will AV systems accommodate

and address these issues? and perhaps do so when

there are multiple OA in the vehicle each with their

own unique set of health conditions/issues.

Most of the participants we spoke to could be

considered ‘passenger drivers’ in terms of watching

the road on journeys and alerting the driver to

potential dangers. A theme emerged that doing so

provided a ‘sense of control’ thereby reducing

passenger anxiety. AV systems could provide

visibility of identified dangers to passengers or

respond appropriately to passenger alerts, thereby

maintaining passenger ‘sense of control’ as they

transition to AV systems/services.

Autonomous Vehicles for Independent Living of Older Adults

301

Figure 1: Disability/Condition informing AV design.

5.4 Mobility as a Service Capabilities

A number of findings in terms of passenger activities

and health issues etc. serve to inform the capabilities

and thus Value Proposition of future MaaS offering

for OA. Firstly, the desired passenger experience of

OA appears to differ to other population cohorts

suggesting MaaS offerings may need to cater

exclusively to OA adults on a designated trip. In this

regard, pre-passenger profiling to ensure OA are

suitably matched for customer journeys appears a

fruitful capability of future offerings. For example, an

AV journey may entail passengers are matched by

age, health conditions and interest. Furthermore, an

available passenger to assist other OA passengers

could make redundant the need for additional manned

AV journey assistance. A mechanism to incentivise

an available customer to assist other OA passengers

through reduced fares etc. or a passenger capable of

assuming control of the AV may need to be incenti-

vised and mandatorily available for each journey.

Furthermore, OA may have certain pre-requirements

for the journey in addition to needing assistance, such

as ‘seat preference’, ‘journey breaks’ etc.

5.5 MaaS Business Models for OA

Finally, MaaS business models will need to be

developed (taking into account MaaS capabilities) to

offer solutions to shortcomings in existing ‘Public

transport’ and ‘community organisations’ offerings.

Whilst services such as Uber, Lyft and Mytaxi in

Ireland offer urban services with some ‘ridesharing’

services being rolled out, they are currently

unavailable to suburban and rural customers due to

current shortcomings in economies of scale. The

comparatively limited population density of suburban

and rural areas requiring a rethink of how expected

customer experiences can be met. Furthermore,

findings suggest that norms of ride-sharing and trust

are not yet established in rural areas of Ireland.

Whether such norms and ‘trust’ issues are cultural or

exist in other regions in Europe will require careful

cross-country analysis and future comparative studies

of OA in differing regional territories.

6 CONCLUSION

This paper presented context, motivation and initial

findings from an exploratory qualitative pilot of

suburban and rural OA in Ireland. Findings suggest

that as AV systems assume driving control from

humans, existing technology adoption models such as

TAM2 and UTAUT2 (Venkatesh & Bala 2008;

Venkatesh et al. 2016) are currently inadequate in

predicting conditions for adoption of future complex

AV systems and services by Older Adults. This is due

to such aspects as ‘Trust’ (vehicle driving safety,

ensuring passenger safety with unique requirements,

ride-sharing safety etc.), ‘Transparency’

(communicate identification of hazards,

communicate the journey etc.), ‘Social Etiquette’

(consider and be conscientious to different passengers

and road users) and ‘Capability’ (accommodate

physical and cognitive disabilities/impediments etc.)

as being potentially important variables to

considering realising robust models. Discussion

highlighted several important research directions and

challenges in OA AV research looking forward

applicable to multiple research domains. For instance,

the social impact of AV on family relations, the

impact on OA cognitive ability/deterioration and the

design of MaaS business models for regions, are just

some of the research challenges raised.

Initial thematic findings presented will inform the

research focus and design of a cross-European

qualitative study of Older Adults in urban, suburban

and rural regions. The next step will be refinement of

an interview protocol based on insights and thematic

findings according to the 5 interrelated work streams

identified. The countries chosen for this study will be

Ireland, Italy, Germany and the UK. Final themes will

furthermore inform automotive HMI/HCI design

guidelines as well as proposing a technology

acceptance model of Older Adult acceptance of

Autonomous Vehicles.

This research project was supported by funding

from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) and Intel

Corp.

SMARTGREENS 2018 - 7th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

302

REFERENCES

Abraham, H. et al., 2016. Autonomous Vehicles, Trust and

Driving Alternatives : A survey of consumer

preferences. AgeLab, MIT.

Chihuri, S. et al., 2016. Driving cessation and health

outcomes in older adults. Journal of the American

Geriatrics Society, 64(2), pp.332–341.

Choi, M., Lohman, M. & Mezuk, B., 2014. Trajectories of

cognitive decline by driving mobility: evidence from

the Health and Retirement Study. International Journal

of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(5), pp.447–453.

Connolly, S., Finn, C. & O’Shea, E., 2011. Rural Ageing in

Ireland: Key Trends and Issues, Irish Centre for Social

Gerontology, NUI Galway. Retrieved January, 10,

p.2017

Craik, F. et al., 1996. Aging and memory: Implications for

skilled performance. In Aging and skilled performance:

Advances in theory and applications, (4) pp. 113–137.

Duncan, M. et al., 2015. Using Automated Vehicles,

Enhanced mobility for aging populations using

automated vehicles (No. BDV30 977-11). Florida.

Dept. of Transportation.

Eby, D.W. et al., 2015. Keeping Older Adults Driving

Safely: A Research Synthesis of Advanced In-Vehicle

Technologies. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for

Traffic Safety

Edwards, J.D. et al., 2009. Driving cessation and health

trajectories in older adults. Journals of Gerontology -

Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences,

64(12), pp.1290–1295.

Eurostat, 2015. People in the EU – population projections.

Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-ex

plained/index.php/People_in_the_EU_–_population_p

rojections.

Ghazizadeh, M., Lee, J.D. & Boyle, L.N., 2012. Extending

the Technology Acceptance Model to assess

automation. Cognition, Technology & Work, 14(1),

pp.39–49.

Harbers, M. & Achterberg, P., 2012. Europeans of

retirement age : chronic diseases and economic activity.

Bilthoven: RIVM

Holley-moore, G. & Creighton, H., 2015. The Future of

Transport in an Ageing Society. Age UK, London.

Iakovidis, I., 2015. The Silver Economy Opportunities for

European Regions,

IIHS, 2016. Older drivers. Available at: http://www.

iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/older-drivers/fatalityfacts/older-

people.

Shaw, L. et al., 2010. Seniors’ perceptions of vehicle safety

risks and needs. American Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 64(2), pp.215–224.

Shergold, I., Lyons, G. & Hubers, C., 2015. Future mobility

in an ageing society - Where are we heading? Journal

of Transport and Health, 2(1), pp.86–94.

Souders, D. & Charness, N., 2016. Challenges of Older

Drivers ’ Adoption of Advanced Driver Assistance

Systems and Autonomous Vehicles. In International

Conference on Human Aspects of IT for the Aged

Population.

Strategy Analytics, 2017. Accelerating the Future: The

Economic Impact of the Emerging Passenger Economy,

Available at: www.strategyanalytics.com.

Venkatesh, V. et al., 2016. Unified Theory of Acceptance

and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road

Ahead. Jais, 17(5), pp.328–376.

Venkatesh, V. & Bala, H., 2008. Technology Acceptance

Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions.

Decision Sciences, 39(2), pp.273–315.

Wan, He; Larsen, L., 2014. Older Americans With a

Disability: 2008−2012. Available at: https://www.

census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2

014/acs/acs-29.pdf.

Westlund, H. & Kobayashi, K., 2013. Social Capital and

Rural Development in the Knowledge Society. Edward

Elgar Publishing

Yang, J. & Coughlin, J. F., 2014. In-vehicle technology

for self-driving cars: Advantages and challenges for

aging drivers. International Journal of Automotive

Technology, 15(2), pp.333-340.

Young, K. L., Koppel, S. & Charlton, J. L., 2017. Toward

best practice in Human Machine Interface design for

older drivers : A review of current design guidelines.

Accident Analysis and Prevention, 106, pp.460–467.

Autonomous Vehicles for Independent Living of Older Adults

303