Impact of Culture Dimensions Model on Cross-Cultural Website

Development

Gatis Vitols

1

and Yukako Vitols-Hirata

2

1

Faculty of Information Technologies, Latvia University of Agriculture, Liela street 2, Jelgava, Latvia

2

Cognitee Inc., Kami-Osaki 2-13-32-802, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords: Cross-Cultural Development, Localization, Culture Dimensions Model, Usability.

Abstract: In the cross-cultural website design literature, three strategies are often mentioned: globalization,

internationalization and localization. Most cited are the localization and the internationalization. To develop

localised websites for different cultures two models are widely applied. One is the culture marker model,

and the other is the culture dimensions model. Marker model identify system elements (i.e. calendar,

language, date formats) that require modifications. Since introduction of this model, authors have widely

applied marker identification for cross-cultural system design. Culture dimensions model includes multiple

subordinate models or cultural dimension models that have been derived from previously published cultural

META models. With the culture models and dimensions included in these models, authors try to analyse

and compare various cultures in order to acquire internal characteristics of target cultures. However culture

dimensions model application in information and communication technology field for system development

is still questionable. There is a need to perform more research on application of this model for development

of methods for more usable and accessible website design. The aim of this article is to perform literature

review on impact of culture dimensions model on cross-cultural website development for further

development of application methodologies. It can be concluded that analysis of the culture dimensions

(particularly Hofstede model) facilitates the process of gathering culture preferences and identification of

evaluation methods for target users and can be applied for cross-cultural website design. Culture dimensions

affect website’s graphical information, design of navigation, design of text, creation of interaction elements,

and design of input elements.

1 INTRODUCTION

Localization and internationalization of information

systems is crucial, since expansion of globalization

processes allow businesses to reach wide audience

worldwide (Callahan 2006b; Gould and Zakaria

2000; Salgado et al. 2011). Multinational

corporations, universities, governments and others

try to address users from various countries and

cultural backgrounds. Only 8-10% of the world

population and 35% of website users use English as

their primary communication language (Aykin 2005;

Takasaki and Mori 2007).

People from various cultures not only speak

different languages, but also think and act

differently. This statement is proven in researches

from various scientific fields, including information

and communication technology (ICT) (Rau et al.

2011; Reinecke and Gajos 2011). Two models are

widely applied for cross-cultural web system

development (Ying 2007). One is the culture marker

model, and the other is the culture dimensions model

(Ying 2007).

Cross-cultural website elements that require

modifications are called the cultural markers. This

term was introduced by Barber and Badre (Barber

and Badre 1998). Since then, other authors have also

widely applied this model and admitted that marker

identification and modification is accessible

solutions for cross-cultural website design

(Fitzgerald 2004; Smith et al. 2004; Kondratova et

al. 2007). Culture dimensions model includes

multiple subordinate models or cultural dimensions

that have been derived from previously published

cultural meta models (Ford and Kotze 2005) and in

combination with culture marker model could

further improve the cross-cultural website

development process.

540

Vitols, G. and Vitols-Hirata, Y.

Impact of Culture Dimensions Model on Cross-Cultural Website Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0006781005400546

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2018), pages 540-546

ISBN: 978-989-758-298-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

The aim of this article is to perform literature

review on impact of culture dimensions model on

cross-cultural website development for further

development of application methodologies.

2 EXISTING CULTURE

DIMENSIONS MODELS FOR

APPLICATION TO WEBSITE

DEVELOPMENT

Since the bloom of World Wide Web (WWW),

website developers introduce multiple guidelines for

website development with improved usability. Only

around year 2000 more and more research appeared

that address the cross-cultural usability issues. There

are guidelines for localization also from software

developers, for example Microsoft has

internationalization guidelines that address image

content, layout of graphics, etc. (Kamppuri 2011).

Mostly these guidelines are derived from the cultural

marker model application researches (Aykin and

Milewski 2005; Rau et al. 2011; Vitols et al. 2012).

Another existing model is culture dimensions model.

Culture dimensions are basically culture models

that are emerged from statistical analyses of large

studies executed in various countries (Kamppuri

2011). Sources for culture dimensions are mainly

anthropological theories and models (Regan 2005).

For example, a well-known dimension for culture

comparison is the "context dimension" presented by

Hall.

In the ICT field there have been attempts to

create a format that would allow analysing and

translating culture characteristics for improved

development process of information systems. The

idea about the relation between cultural dimension

and information system design for the first time was

introduced by Marcus and Gould (Marcus and Gould

2000). In the last 60 years more than 25 various

culture analysis dimensions have been identified

(Schadewitz 2009; Alostath et al. 2009). However,

for information system design Hall and Hofstede

dimensions are most researched and applied (Singh

and Baack 2004; Sondergaard 1994; Pavlou and

Chai 2002; Reece et al. 2010; Callahan 2006b;

Robbins and Stylianou 2003; Gould and Zakaria

2000; Jablin and Putnam 2001; Ying and Lee 2008;

Choi et al. 2005; Leidner and Kayworth 2008;

Gevorgyan and Manucharova 2009; Knight et al.

2009; Kale 2006; Ford and Gelderblom 2003; Wurtz

2005; Xinyuan 2005; Simon 1999; Duygu Bedir

Eristi 2009).

In studies on designing the cross-cultural web

pages, one more dimension has been introduced and

applied which is cognitive styles in various cultures,

especially related to information layout (Nishbett

2003; Matsuda and Nishbett 2001; Nishbett and

Miyamoto 2005; Cui et al. 2015; Vatrapu and

Suthers 2007; Ying and Lee 2008). Ying and Lee in

their study (Ying and Lee 2008) show that people

from various cultures browse websites contents in

different ways and that this difference is closely

related to the culture cognitive style. These authors,

based on data about how people from various

cultures browse WWW, divide cultures into two

groups: "analytically thinking" and "holistically

thinking". This division has already been known for

many years in psychology field. Nishbett was the

person who widely started to use it in his cross-

cultural studies (Matsuda and Nishbett 2001;

Nishbett 2003; Nishbett and Miyamoto 2005).

Hall suggested (Hall 1976; Hall 2000; Hall 1959)

to compare cultures based on communication styles.

Hall defined the following dimensions:

Time;

Space;

Context;

Message speed.

From Hall dimensions, context and time

dimensions are mentioned for application for cross-

cultural system design (Marcus and Rau 2009;

Wurtz 2005; Isa et al. 2007).

From these models, the Hofstede model and its 5

dimensions are most applied for cross-cultural

system analysis, requirements gathering and

usability evaluation. This model is also most cited

(Kamppuri 2011) and when searching this model

application in computer science field in SCOPUS

database since beginning of index until September

2017, it can be seen that model has been applied in

more than 350 studies. Hofstede defined 5

dimensions (Hofstede et al. 2010) derived from

analysis of 76 countries as follows:

Power distance;

Individualism versus collectivism;

Masculinity versus femininity;

Uncertainty avoidance;

Long-term versus short-term orientation.

In 2010 Hofstede also added sixth dimension to

the model Indulgence versus Restraint. However as

there is a limited research on this recently added

dimension and dimension can be considered

ambiguous, analysis of this dimension is omitted in

this research.

Impact of Culture Dimensions Model on Cross-Cultural Website Development

541

3 HOFSTEDE CULTURE

DIMENSIONS MODEL FOR

APPLICATION TO WEBSITE

DEVELOPMENT

In this section existing literature on Hofstede culture

model application for website development are

analysed.

For literature analysis articles from Computer

Science field in SCOPUS database has been

selected. Keywords “culture models website

development” has been used to identify set of

articles for analysis.

Hofstede provides dimension calculations, acquiring

numerical evaluation for each of the dimensions for

most of the World cultures. Such evaluation allows

researchers to apply these dimensions in various

science fields more easily.

Hofstede culture model impact for cross-cultural

website development results are summarized in

Table 1. Dimension calculations can be interpreted

variously to define which is high or low, for

example power distance culture.

Power Distance. From analysed publications,

results shows that high power distance dimension

have impact on people preference to content. For

example websites from high power distance require

more information about administration and hierarchy

of the organisation or owner of the website

(Gevorgyan and Manucharova 2009). Also

developers should include symbolic emphasis on

social and national order. Power distance systems

also include more locked and controlled access

sections which are visible for other users (Marcus

and Gould 2000; Marcus and Krishnamurthi 2009).

High power distance cultures (i.e. Malaysia), also

have more emphasis on person biographies,

organisational charts, welcome speech from owners

of the website, rector of university, head of

organisation, etc., formal logos and certificates.

(Robbins and Stylianou 2003; Ahmed et al. 2009;

Callahan 2006a). Developers should pay attention to

text content as high power distance cultures pay

attention to proper application of person titles

(Ahmed et al. 2009). Low power distance cultures

prefer more navigation and control on website or

system. Such cultures prefer 24 hour support,

availability to input feedback (i.e. questioners,

reviews), podcasts, RSS and equivalent services

(Gevorgyan and Manucharova 2009).

Individualism Versus Collectivism. Collective

cultures prefer web systems that have functionality

to join groups and support many to many

communication style (i.e. web forums, public chats,

loyalty programmes, social network integration)

(Gevorgyan and Manucharova 2009; Li et al. 2011;

Kuljis and Halloran 2010; Pfeil et al. 2006)

Collective cultures prefer more localised content and

non-localization can impact e-commerce

performance particularly in high collectivism culture

(Jarvenpaa et al. 2006; Kang 2009) Collective

cultures pay more attention to elements that

represent other people opinion, such as popularity

charts (i.e. most downloaded mobile application,

most viewed video), other people opinion on product

or service (Choi et al. 2005). Collective cultures

prefer introduction page of web system, while

cultures where individualism dominate, such page is

considered redundant (Kim et al. 2009; Nielsen

1999). Individualist cultures prefer more content

where single person story and success is

emphasized, while collective cultures prefer more

images and group photos from various situations of

life with emphasis of history, experience and

tradition (Wurtz 2005; Callahan 2006a; Marcus and

Gould 2000; Marcus and Alexander 2007). Element

layout for high individualism cultures is more

asymmetric while collective cultures prefer

symmetrical layout.

Masculinity Versus Femininity. Masculine

cultures prefer website content with such elements

as company annual reports, financial success stories

and images with objects (Robbins and Stylianou

2003) while famine cultures prefer more images

with people (Callahan 2006a). Masculine cultures

also prefer web content orientated to traditions,

gender, family and age differences as well as content

put emphasis on competition in various fields

(Marcus and Gould 2000; Kale 2006). In contrast

more feminine cultures do not emphasise gender

role, rather website aesthetics, impact on

environment and elements that offer collaboration

(i.e. comments, adding content, chatting) are valued

(Marcus and Gould 2000; Kale 2006).

Uncertainty Avoidance. Cultures where uncertainty

avoidance is higher are more cautious for online

purchases and websites that has less description and

more exploratory design in contrast cultures with

low uncertainty avoidance does not have significant

impact of less descriptive content (Vishwanath

2003). For example South Korean (high uncertainty

avoidance culture) charity websites always include

detailed description for donation, in the same time

English versions of these websites does not include

detailed descriptions (Kuljis and Halloran 2010).

High uncertainty avoidance cultures prefer more

secure websites with explained security policies

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

542

(Kale 2006), clear and simple web content with

limited choices, more explanation about website

elements, such as what will happen when you press

button, simple navigation structures and application

of colours and animation to keep users browsing

experience clear and understandable. (Marcus and

Gould 2000; Marcus and Gould 2001). For example

high uncertainty cultures (i.e. Korea, Japan)

Facebook has less uncertain elements and functions,

such as button “People you may know” while such

functionality is available to low uncertainty cultures

(i.e. United States) (Marcus and Krishnamurthi

2009).

In contrast low uncertainty avoidance cultures

typically have more complex navigation structure,

wide choice options for selection, saturation of

various elements that does not have clearly

described outcome, such as popup window can

suddenly open (Marcus and Gould 2000).

Long-term Versus Short-term Orientation. Long-

term oriented cultures prefer websites with

availability of search engines, navigation map,

frequently asked questions and history of website

(Robbins and Stylianou 2003). Content of long-term

oriented cultures have more message and structure

emphasis on practical value of product or service,

time investment to reach the aim (Marcus and Gould

2000).

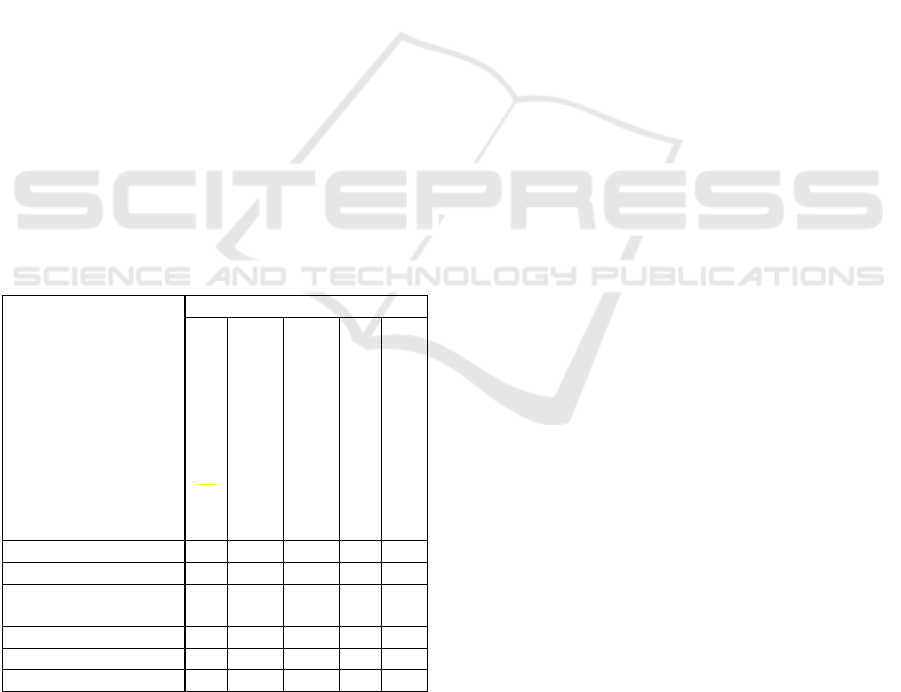

Table 1: Hofstede culture model impact for cross-cultural

website development.

Website elements

Dimensions

Power distance

Individualism versus

collectivism

Masculinity versus

femininity

Uncertainty avoidance

Long

-

term versus short

-

term orientation

Elements layout

+

+

-

-

-

Use of proper language

+

-

+

+

+

Graphics elements

contents

+

+

+

+

+

Navigation structure

-

+

+

+

+

Interaction options

-

+

+

-

-

Design aesthetics

-

-

+

-

-

Short term oriented cultures prefer content that

emphases truth and fast message delivery, for

example users must immediately understand the

purpose and value of website. In e-commerce

research it can be seen that users from short term

oriented cultures prefer to see single good

representation of product or service – image or video

while long-term oriented cultures need more images

about product, purpose of product and application

scenarios (Marcus and Alexander 2007).

The "power distance" dimension affects website

content organization, usage of people status in texts,

application of official symbolic, application of signs

reflecting quality, layout and usage of formal

language.

The "individualism versus collectivism"

dimension affects amount of provided options in

website, satiation of graphical information,

adaptation options, satiation of overall information,

organization of content, creation of website

navigation.

The "masculinity versus femininity" dimension

affects formulation of content, aesthetical design,

usage of graphics, amount of offered options and

organization of task execution.

The "uncertainty avoidance" dimension affects

reflection of security elements, formulation of

communication and features of trust, satiation of

information, design of navigation, usage of tips and

complimentary information and usage of graphics.

The "long-term versus short-term orientation"

dimension affects usage of metaphors, formulation

of content, and design of navigation and usage of

graphics.

Performed literature review suggests that data

retrieved from Hofstede dimensions applications for

website usability studies can be used for further

development and improvement of website usability

guidelines, as well as development of developers

support tools.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Analysis of the impact given by the culture

dimensions is an important step for cross-cultural

website design. From the published culture

dimensions, Hofstede published the important

dimensions for cross-cultural website design that are

most researched and applied in website

development. Analysis of the culture dimensions

facilitates the process of gathering culture

preferences and identification of evaluation methods

for target users.

From data represented in the article, it can be

seen that cross-cultural website developers should

pay more attention to navigation structure,

application of graphical elements and contents of

these elements as well as use of proper language

Impact of Culture Dimensions Model on Cross-Cultural Website Development

543

(e.g. direct translation is not enough) are variables in

multiple cultures.

From literature analysis it can be seen that

Hofstede dimensions for website development

overlap as, for example, need for high context

cultures and collective cultures have similar

demands for website design.

There is a need for cultural advisor tools

development as assistants for developers who want

to develop product or service websites for different

cultures.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, T., Mouratidis, H. and Preston, D., 2009. Website

Design Guidelines: High Power Distance and High-

Context Culture. International Journal of Cyber

Society and Education, 2(1), pp.47–60.

Aykin, N., 2005. Overview: Where to Start and What to

Consider. In N. Aykin, ed. Usability and

Internationalization of Information Technology.

New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.,

pp. 3–20.

Aykin, N. and Milewski, A.E., 2005. Practical Issues and

Guidelines for International Information Display. In

N. Aykin, ed. Usability and Internationalization of

Information Technology. New Jersey: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp. 21–51.

Alostath, J., Almoumen, S. and Alostath, A., 2009.

Identifying and Measuring Cultural Differences in

Cross-Cultural User-Interface Design. In N. Aykin,

ed. Proceedings of Third International Conference

on Internationalization, Design and Global

Development, IDGD 2009. San Diego: Springer-

Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 3–12.

Barber, W. and Badre, A., 1998. Culturability: The

Merging of Culture and Usability. In Proceedings

of the 4th Conference on Human Factors and the

Web. Basking Ridge, New Jersey: AT&T Labs.

Callahan, E., 2006a. Cultural Similarities and Differences

in the Design of University Web Sites. Journal of

Computer Mediated Communication, 11(1),

pp.239–273.

Callahan, E., 2006b. Interface Design and Culture. Annual

Review of Information Science and Technology,

39(1), pp.255–310.

Choi, B. et al., 2005. A Qualitative Cross-National Study

of Cultural Influences on Mobile Data Service

Design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Portland,

USA: ACM Press, pp. 661–670.

Cui, T., Wang, X. and Teo, H.-H., 2015. Building a

Culturally-Competent Web Site. Journal of Global

Information Management, 23(4), pp.1–25.

Available at: http://services.igi-global.com/

resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/JGIM.201510

0101 [Accessed November 17, 2017].

Duygu Bedir Eristi, S., 2009. Cultural Factors in Web

Design. Journal of Theoretical and Applied

Information Technology, 9(2), pp.117–132.

Fitzgerald, W., 2004. Models for Cross-Cultural

Communications for Cross Cultural Website

Design, Ottawa.

Ford, G. and Gelderblom, H., 2003. The Effects of Culture

on Performance Achieved Through the Use of

Human Computer Interaction. In J. Eloff et al., eds.

Proceedings of the 2003 Annual Research

Conference of the South African Institute of

Computer Scientists and Information Technologists

on Enablement Through Technology, SAICSIT ’03.

Gauteng: South African Institute for Computer

Scientists and Information Technologists, pp. 218–

230.

Ford, G. and Kotze, P., 2005. Designing Usable Interfaces

with Cultural Dimensions. In M. F. Costabile and F.

Paterno, eds. Proceedings of Human-Computer

Interaction - INTERACT 2005: IFIP TC13

International Conference. Rome: Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 713–726.

Gevorgyan, G. and Manucharova, N., 2009. Does

Culturally Adapted Online Communication Work?

A Study of American and Chinese Internet Users’

Attitudes and Preferences Toward Culturally

Customized Web Design Elements. Journal of

Computer Mediated Communication, 14(2),

pp.393–413.

Gould, E.W. and Zakaria, N., 2000. Applying Culture to

Website Design: A Comparison of Malaysian and

US Websites. In Proceedings of IEEE Professional

Communication Society International Professional

Communication Conference. New Jersey: IEEE

Educational Activities Department Piscataway, pp.

161–171.

Hall, E.T., 1976. Beyond Culture, Anchor Books.

Hall, E.T., 2000. Context and Meaning. In L. A. Samovar

and R. E. Porter, eds. Intercultural Communication.

Belmont, USA: Wadsworth Publishing, pp. 34–43.

Hall, E.T., 1959. The Silent Language, New York, USA:

Doubleday.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J. and Minkov, M., 2010.

Cultures and Organizations: Software for the Mind

Third ed., New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ying, D., 2007. A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study on

Users’ Perception of the Webpage: With the Focus

on Cognitive Style of Chinese, Korean and

American. Korea Advanced Institute of Science and

Technology.

Ying, D. and Lee, K.-P., 2008. A Cross-Cultural

Comparative Study of Users’ Perceptions of a

Webpage: With a Focus on the Cognitive Styles of

Chinese, Koreans and Americans. International

Journal of Design, 2(2), pp.19–30.

Isa, W.A.R.W.M., Nor Laila, N. and Shafie, M., 2007.

Incorporating the Cultural Dimensions into the

Theoretical Framework of Website Information

Architecture. In Proceedings of 12th International

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCII.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

544

Beijing: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp.

212–221.

Jablin, F. and Putnam, L., 2001. Organizational Culture. In

F. Jablin and L. Putnam, eds. The New Handbook of

Organizational Communication. Thousand Oaks:

Sage Publications, pp. 291–317.

Jarvenpaa, S., Tractinsky, N. and Saarinen, L., 2006.

Consumer Trust in an Internet Store: A Cross-

Cultural Validation. Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication, 5(2), p.Not paged.

Kale, S.H., 2006. Designing Culturally Compatible

Internet Gaming Sites. UNLV Gaming Research &

Review Journal, 10(1), pp.41–50.

Kamppuri, M., 2011. Theoretical and Methodological

Challenges of Cross-Cultural Interaction Design.

University of Eastern Finland.

Kang, K., 2009. Supportive Web Design for Users from

Different Culture Origins in E-Commerce. In N.

Aykin, ed. Proceedings of Third International

Conference on Internationalization, Design and

Global Development, IDGD 2009. San Diego,

USA: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 467–

474.

Kim, H., Coyle, J. and Gould, S., 2009. Collectivist and

Individualist Influences on Website Design in South

Korea and the U.S.: A Cross-Cultural Content

Analysis. Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication, 14(3), pp.581–601.

Knight, E., Gunawardena, C. and Aydin, C.H., 2009.

Cultural Interpretations of the Visual Meaning of

Icons and Images Used in North American Web

Design. Educational Media International, 46(1),

pp.17–35.

Kondratova, I., Goldfarb, I. and Aykin, N., 2007. Color

Your Website: Use of Colors on the Web. In N.

Aykin, ed. Usability and Internationalization.

Global and Local User Interfaces. Lecture Notes in

Computer Science. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer

Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 123–132.

Kuljis, J. and Halloran, P., 2010. Is It Important to Study

Cultural Differences? Journal of Computing and

Information Technology, 18(2), pp.121–123.

Leidner, D. and Kayworth, T., 2008. An Overview of

Culture and IS. In D. Leidner and T. Kayworth, eds.

Global Information Systems: The Implications of

Culture for IS Management. Burlington, USA:

Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 1–6.

Li, H., Rau, P.-L.P. and Hohmann, A., 2011. The Impact

of Cultural Differences on Instant Messaging

Communication in China and Germany. In P.-L. P.

Rau, ed. Proceedings of 4th International

Conference on Internationalization, Design and

Global Development, IDGD 2011. Orlando, USA:

Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 75–84.

Marcus, A. and Alexander, C., 2007. User Validation of

Cultural Dimensions of a Website Design. In N.

Aykin, ed. UI-HCII’07 Proceedings of the 2nd

International Conference on Usability and

Internationalization. Beijing, China: Springer-

Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 160–167.

Marcus, A. and Gould, E.W., 2000. Crosscurrents:

Cultural Dimensions and Global Web User-

Interface Design. ACM Interactions, 7(4), pp.32–

46.

Marcus, A. and Gould, E.W., 2001. Cultural Dimensions

and Global Web Design: What? So What? Now

What?, New Jersey, USA.

Marcus, A. and Krishnamurthi, N., 2009. Cross-Cultural

Analysis of Social Network Services in Japan,

Korea, and the USA. In N. Aykin, ed. Proceedings

of Third International Conference on

Internationalization, Design and Global

Development, IDGD 2009. San Diego, USA:

Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 59–68.

Marcus, A. and Rau, P.-L.P., 2009. International and

Intercultural User Interfaces. In C. Stephanidis, ed.

The Universal Access Handbook. Boca Raton,

USA: CRC Press, pp. 156–167.

Matsuda, T. and Nishbett, R., 2001. Attending Holistically

Versus Analytically: Comparing the Context

Sensitivity of Japanese and Americans. Personality

and Social Psychology, 81(5), pp.922–934.

Nielsen, J., 1999. Designing Web Usability, Indianapolis,

USA: Peachpit Press.

Nishbett, R., 2003. The Geography of Thought: How

Asians and Westerners Think Differently...and Why,

New York, USA: The Free Press.

Nishbett, R. and Miyamoto, Y., 2005. The Influence of

Culture: Holistic Versus Analytic Perception.

Trends in Cognitive Science, 9(10), pp.467–473.

Pavlou, P. and Chai, L., 2002. What Drives Electronic

Commerce Across Cultures? A Cross-Cultural

Empirical Investigation of the Theory of Planned

Behavior. Electronic Commerce Research, 3(4),

pp.240–253.

Pfeil, U., Zaphiris, P. and Ang, C.S., 2006. Cultural

Differences in Collaborative Authoring of

Wikipedia. Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication, 12(1), pp.88–113.

Rau, P.-L.P., Plocher, T. and Choong, Y.-Y., 2011. Cross-

Cultural Web Design. In R. Proctor and K.-P. Vu,

eds. Handbook of Human Factors in Web Design.

Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 677–698.

Reece, G. et al., 2010. Identifying Cultural Design

Requirements for and Australian Indigenous

Website. In Proceedings of the 11th Australasian

User Interface Conference: AUIC2010.

Darlinghurst, Australia: Australian Computer

Society, pp. 89–97.

Regan, T., 2005. Cross-Cultural Interface Design:

Determining Design Elements and Considerations

for International Business to Consumer Websites,

Chicago.

Reinecke, K. and Gajos, K., 2011. One Size Fits Many

Westerners: How Cultural Abilities Challenge UI

Design. In Proceedings of the Workshop on

Dynamic Accessibility: Detecting and

Accommodating Differences in Ability and Situation

at CHI’11. Vancouver: ACM Press, pp. 1–8.

Robbins, S. and Stylianou, A., 2003. Global Corporate

Impact of Culture Dimensions Model on Cross-Cultural Website Development

545

Web Sites: an Empirical Investigation of Content

and Design. Information and Management, 40(3),

pp.205–212.

Salgado, L.C. de C., Souza, C.S. de and Leitao, C.F.,

2011. Using Metaphors to Explore Cultural

Perspectives in Cross-Cultural Design. In P.-L. P.

Rau, ed. Proceedings of 4th International

Conference on Internationalization, Design and

Global Development, IDGD 2011. Orlando, USA:

Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 94–103.

Schadewitz, N., 2009. Design Patterns for Cross-cultural

Collaboration. International Journal of Design,

3(3), pp.37–53.

Simon, S.J., 1999. A Cross Cultural Analysis of Web Site

Design: An Empirical Study of Global Web Users.

In Proceedings of 7th Cross-Cultural Consumer

and Business Studies Research Conference.

Cancun: Brigham Young University, pp. 1–12.

Singh, N. and Baack, D., 2004. Web Site Adaptation: A

Cross-Cultural Comparison of U.S. and Mexican

Web Sites. Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication, 9(4), p.Not paged.

Smith, A. et al., 2004. A Process Model for Developing

Usable Cross-Cultural Websites. Interacting with

Computers, 16(1), pp.63–91.

Sondergaard, M., 1994. Research Note: Hofstede’s

Consequences: A Study of Reviews, Citations and

Replications. Organization Studies, 15(3), pp.447–

456.

Takasaki, T. and Mori, Y., 2007. Design and Development

of a Pictogram Communication System for Children

Around the World. In IWIC’07 Proceedings of the

1st International Conference on Intercultural

Collaboration. Kyoto, Japan: Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 193–206.

Vatrapu, R. and Suthers, D., 2007. Culture and

Computers: A Review of the Concept of Culture

and Implications for Intercultural Collaborative

Online Learning. In IWIC’07 Proceedings of the 1st

International Conference on Intercultural

Collaboration. Kyoto, Japan: Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 260–275.

Vishwanath, A., 2003. Comparing Online Information

Effects: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Online

Information and Uncertainty Avoidance.

Communication Research, 30(6), pp.579–598.

Vitols, G., Arhipova, I. and Hirata, Y., 2012. Culture

Colour Preferences for Cross-Cultural Website

Design. In Proceedings of the 5-th International

Scientific Conference on Applied Information and

Communication Technologies AICT 2012. Jelgava:

LUA, pp. 20–26.

Wurtz, E., 2005. A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Websites

from High-Context Cultures and Low-Context

Cultures. Computer-Mediated Communication,

11(1).

Xinyuan, C., 2005. Culture-Based User Interface Design.

In N. Guimaraes and P. Isaias, eds. Proceedings of

the IADIS International Conference Applied

Computing. Algarve: IADIS Press, pp. 127–132.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

546