A Classification Taxonomy for Public Services in Iran

Fereidoon Shams Aliee

1

, Reza Bagheriasl

2

, Amir Mahjoorian

3

, Maziar Mobasheri

2

, Faezeh Hosieni

2

and Delaram Golpayegani

1

1

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

2

Information Technology Organiztion of Iran, Tehran, Iran

3

Service-Oriented Enterprise Achitecture Laboratory, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

d.golpayegani@mail.sbu.ac.ir

Keywords:

Business Reference Model, Public Services, Classification, National Enterprise Architecture Framework.

Abstract:

These days public sector provides numerous services to citizens. Identifying and managing these services is

needed for establishing a national Business Reference Model (BRM). Classifying services according to their

functionality provides a great view of the current state of public services and facilitates the government policy-

making. This classification taxonomy can be considered as a part of the BRM. In this paper, we propose a

functional classification taxonomy of the Iranian public services including government-to-government (G2G),

government-to-business (G2B), and government-to-citizens (G2C) services. All of the services provided by

Iranian public agencies fit into this classification. Up to now, more than two thousand of these services are

classified.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past few years, countries adopted Enterprise

Architecture at a national level have increased in num-

ber. In fact, National Enterprise Architecture (NEA)

has become an essential part of e-government plans as

the governments have found out the positive correla-

tion between NEA programs and e-government suc-

cess (Saha, 2009; Ojo et al., 2012).

Business Reference Model (BRM) is an important

component of most of NEA frameworks and it pro-

vides a classification taxonomy of business functions

and services (CIO Council, 2013; Australian Govern-

ment Information Management Office, 2011). From

the government perspective, BRM can have a great

impact on public sector transformation which has had

a crucial role in e-government success (Saha, 2009).

Every government provides a vast range of public

services to its citizens either in a traditional or elec-

tronic way. These services are designed and devel-

oped by different public agencies with different struc-

tures and business areas. This results in duplicated or

fragmented business services and the cross-agency in-

teroperability cannot be guaranteed (Saha, 2010). A

BRM helps the government have a holistic view of

public services which results in making informed e-

government decisions.

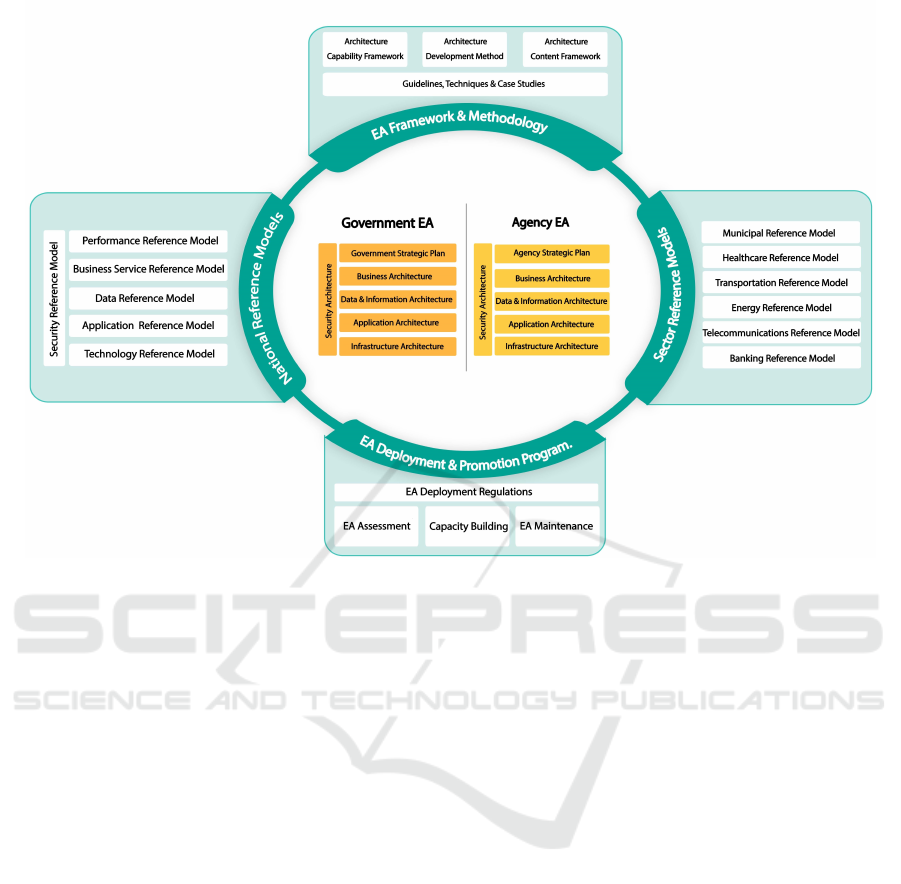

In Iran, the public sector is extremly complex and

dynamic. Thus, one of the biggest challenges of the

government is understanding the current state of busi-

ness processes and services. To overcome this chal-

lenge, Iran’s National Enterprise Architecture Frame-

work (INEAF), shown in Figure 1, considers a busi-

ness service reference model (Shams Aliee et al.,

2017). The national BRM is derived from FEAF

(CIO Council, 2013) and is customized in way that

the government is able to effectively manage public

services and deliver them to citizens. The most dis-

tinctive feature of the national BRM is that it does not

only classify the services according to the sector they

belong to but also it provides a classification which

categorizes public services based on their functional-

ity. Iran’s first foray to implement EA at the govern-

ment level is using this classification to comprehend

the current state of public services in order to make

new policies to achieve the future state.

In this paper, we focus on functional classification

of public services in Iran. In section 2, we have a

brief look at related work on BRM. In section 3, we

discuss that why public services should be classified

based on their functionality and what we expect to

achieve from this classification. Next, we introduce

10 categories of public services that we have identi-

fied. Section 5 provides some information about how

712

Shams Aliee, F., Bagheriasl, R., Mahjoorian, A., Mobasheri, M., Hosieni, F. and Golpayegani, D.

A Classification Taxonomy for Public Services in Iran.

DOI: 10.5220/0006789307120718

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2018), pages 712-718

ISBN: 978-989-758-298-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Figure 1: The Iran’s national EA framework (Shams Aliee et al., 2017).

we have applied this classification to Iranian public

services and we discuss the results. Finally, the con-

clusion is drawn in section 6.

2 RELATED WORK

Since business architecture is an inseparable part of

EA, having a BRM promotes collaboration and con-

sistency. BRM provides a common tool for business

architecture, which can be shared between organiza-

tions (Adams et al., 2014). In this section, we have

a brief look at the structure of BRMs in well-known

NEA frameworks.

FEAF provides a three-layer BRM that represents

classification taxonomy for describing the Federal

governments business functions and services. At the

highest level called mission sector,10 business areas

of the government are identified. The next layer de-

fines what government does by introducing 40 busi-

ness functions each of which related to a specific busi-

ness area. Ultimately, the service layer describes busi-

ness functions at a component level (CIO Council,

2013).

The Australian Government Architecture (AGA)

defines a BRM in addition to a service reference

model. The former describes government business

functions and is structured into three layers: business

areas, lines of business, and sub-functions. The latter

provides a classification taxonomy of services based

on the business they support and their performance

objectives. According to AGA, the service reference

model is also a three-layer hierarchy: service domain,

service type, and component (Australian Government

Information Management Office, 2011).

Similarly, the Korean Government Enterprise Ar-

chitecture (KGEA) considers both business and ser-

vice reference models and underlines that their com-

bination improves the government services integra-

tion and reuse (Lee et al., 2013).

The NewZealand (GEA-NZ) BRM classifies both

government products and services and government

business functions. Business domain, business area,

and business category are levels of the BRM (Deleu

and Clendon, 2015).

So far, we have reviewed the structure of BRM

in some of NEA frameworks and none of them rep-

resents a functional classification taxonomy of public

services. In the following, we will mention some pa-

pers that focused on e-government services classifica-

tion.

(Fonseca and Corr

ˆ

ea, 2014) suggests using

service patterns for modeling and developing e-

government services. In the proposed method, the

A Classification Taxonomy for Public Services in Iran

713

patterns are extracted from existing e-government ser-

vices, classified according to government areas, and

cataloged in a repository. The authors also recom-

mend a template for service pattern description. In

another work, service patterns in public healthcare are

presented and used for designing G2G enterprise ser-

vice bus (Nazih and Alaa, 2011).

3 REASONS BEHIND

FUNCTIONAL

CLASSIFICATION

Service is a well-established concept in different do-

mains of agencies and is a language being compre-

hended by both IT and business people. Service-

orientation also has a positive effect on interoper-

ability, reusability, cost, and agility (Lankhorst and

Bayens, 2009). Therefore, business service is consid-

ered as the key element in the national BRM. To initi-

ate NEA implementation, the Iranian ministry of ICT

asked a number of Iranian public agencies to provide

a catalog of their services. Each service was repre-

sented using a specific service description template.

By analyzing the catalogs, we have noticed four com-

mon errors:

• The agency provided some services that should

have been provided by another agency.

• The agency did not have a clear understanding of

service concept and counted everything it does as

a service.

• The agency has ignored a number of services that

should have provided according to its duties and

responsibilities.

• The agency has ignored some of its online ser-

vices.

These services fit into 14 mission sectors identified

in Figure 2. Although these mission sectors define

business operations of the government, they are not

sufficient for analyzing the current state of business

functions and services for delivering efficient public

services. Classifying public services based on their

functionality may help the government to deliver an

integrated and valuable set of public services. In ad-

dition, classifying public services based on their func-

tionality will expose Achilles heels of the government

in service delivery. The government can use this clas-

sification for policy-making, budget allocation, mon-

itoring agencies performance, and measuring IT im-

provement.

Figure 2: The Iranian government mission sectors.

4 FUNCTIONAL

CLASSIFICATION TAXONOMY

OF PUBLIC SERVICES

By studying a majority of the public services, we fig-

ure out that although different vocabulary is used to

describe them, they share commonalities and can be

classified into 10 categories which fit nearly all of

the government-to-government (G2G), government-

to-business (G2B), and government-to-citizens (G2C)

services. This classification is the result of combined

efforts of experts in different business areas and is

based on the constitution of the Islamic Republic of

Iran. It is worth mentioning that reviewing other gov-

ernments’ services to citizens helped us form the clas-

sification. In the following, we are going to explore

each category in-depth.

1. Establishing laws, regulations, tariffs, and stan-

dards

Description: includes a set of public services that

lead to formation and establishment of new laws, reg-

ulations, tariffs, and standards. These services are

usually provided by legislative agencies.

Type: Governance

Level: National

Examples:

• Codification of law and legislation

• Formulation of a new law

• Levy healthcare tariffs

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

714

2. Validation and qualification assessment

Description: includes services which lead to veri-

fication of a legal or natural person and qualification

assessment of goods or services.

Type: Governance

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Issuing a trading license

• Degree approval and conferment

• Issuance of passport for refugees

3. Monitoring, auditing, and conducting trials

Description: matches the public services that

monitor compliance with laws, policies, or standards

through monitoring, auditing, and conducting trails.

Type: Governance

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Monitoring enterprise architecture laboratories

• Handling customer complaints

4. Enforcing the law

Description: includes services designed for carry-

ing out criminals sentences and imposing fines.

Type: Governance

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Imposing driving fines and penalties

• Confiscating properties

5. Registering public records

Description: consists of a set of services that en-

ables the applicant to submit information or records

in person or by electronic means.

Type: Supportive

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Issuing birth certificate

• Filing price of goods and services

• Keeping birth, marriage, and death records

6. Publishing information, statistics, and records

Description: includes services that generate re-

ports, produce statistics, and provide analysis based

on collected information. Services in this category

may also provide searchable online databases.

Type: Supportive

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Publishing census data

• Looking up birth records

7. Providing funds and benefits

Description: matches the services that provide

grants, funds, or loans to a legal or natural person.

Type: Supportive

Level: National, local

Example:

• Providing funds for university students

• Granting mortgage loans

• Providing concessional loans

8. Training and cultivating culture

Description: includes a set of services that provide

training and education for citizens. Public services in

this category are considered as a complementary for

services in other categories.

Type: Supportive

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Holding academic conferences and symposiums

• Offering online courses

9. Infrastructure investment, development, and

maintenance

Description: consists of a set of services that lead

to development and maintenance of urban, road, com-

munication, etc. infrastructures.

Type: Supportive

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Road maintenance

• Developing railway infrastructure

10. Service operator

Description: includes services that directly pro-

vide services to citizens.

Type: Direct services

Level: National, local

Examples:

• Opening a new account (Banking services)

• Providing vehicle insurance (Insurance services)

• Medical and healthcare services

5 PUBLIC SERVICES

CLASSIFICATION IN

PRACTICE

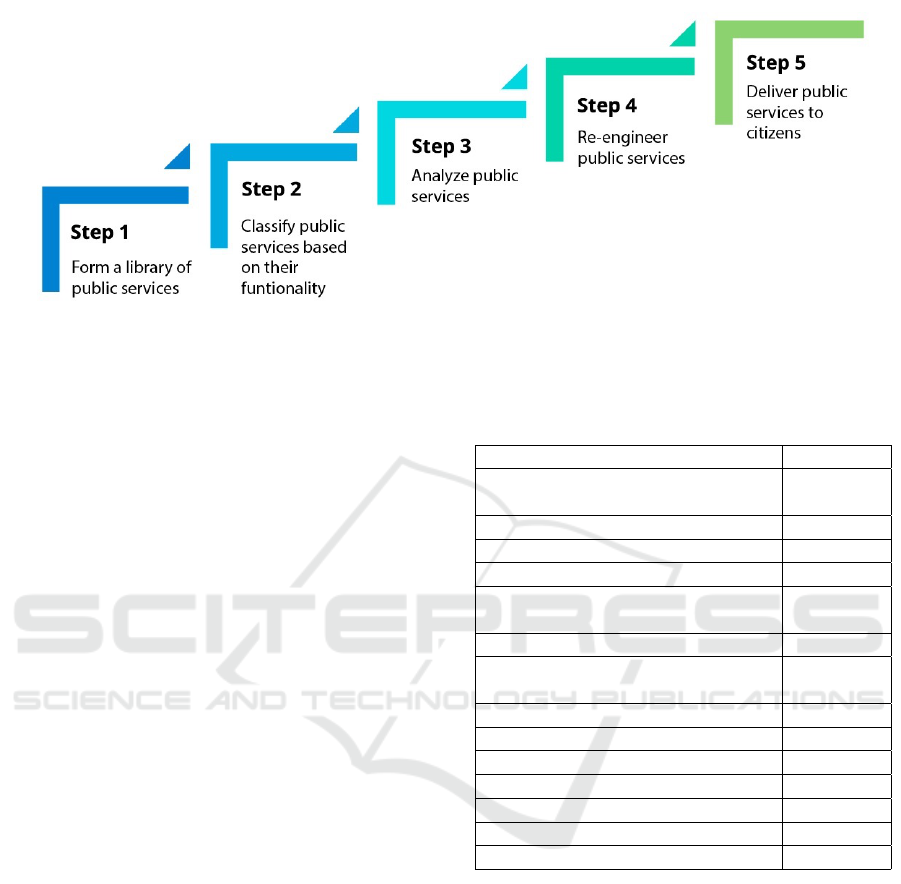

the ultimate goal of the national BRM is to make a

holistic view of public services. The public services

should be accessed and used easily by citizens regard-

less of their location or time. To achieve this, we con-

sider five steps depicted in Figure 3.

A Classification Taxonomy for Public Services in Iran

715

Figure 3: Steps to achieve a holistic view of public services.

Forming a library of public services including ser-

vice catalogs of 95 public agencies is the first step in

achieving a holistic view of public services. All of

the services delivered by an agency are presented us-

ing a predefined service description template. In the

next step, joint meetings of ICT and public agencies

are held to discuss each service in order to identify the

category it falls into. Next, the result of the previous

step is used for discovering the gap between current

and target state of business services not only in a sin-

gle agency but also in the government as a unified en-

tity. Therefore, each agency should re-engineering its

processes and services to narrow the gap and the gov-

ernment has to make new policies and standards based

on the results of the classification process. After ap-

plying the changes, services delivered to citizens. As

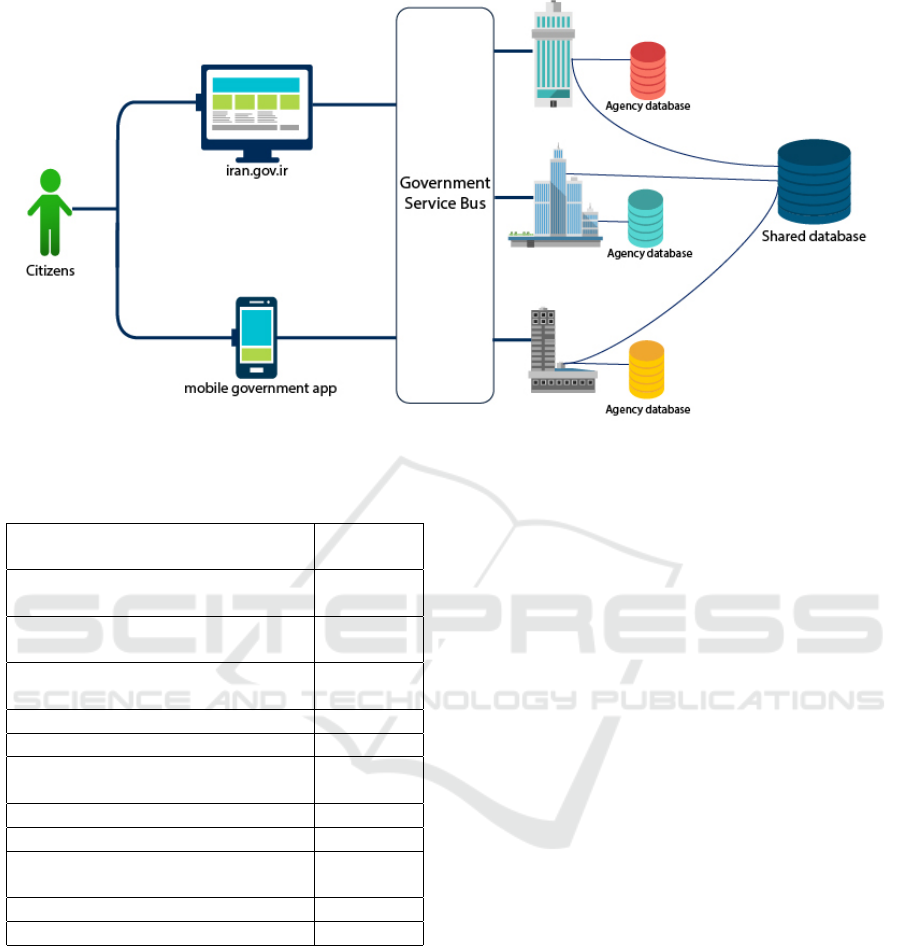

it is shown in Figure 4, the citizens can access the ser-

vices provided by different public agencies through a

single portal (ira, 2018b) or via a mobile application

called mobile government (ira, 2018a).

Up to now, more than two thousand public ser-

vices provided by 95 public agencies are classified.

Table 1 illustrates the result of classifying public ser-

vices according to mission sectors.

Table 2 lists the number of services that match

each category. The results show that the government

is facing a tough challenge managing public services.

A great number of services provided by different pub-

lic agencies but they belong to a limited number of

mission sectors and functional categories. For exam-

ple, almost a half of public services fall into validation

and qualification assessment category which means

that the government provides a variety of services for

people to get permission. But is it necessary to have

more than a thousand services for only giving permis-

sion? Are all of the validation and quality assessment

services being used frequently?

Table 1: Number of public services in each mission sector

in percentage.

Mission sector Percentage

Environment, agriculture, and natu-

ral resources

22%

Cultural and social affairs 11%

Health and well-being 10%

Education and research 10%

Transportation and urban develop-

ment

8%

Industries and businesses 7%

Communication and information

technology

6%

Economic affairs and finance 6%

Energy 6%

Internal affairs 5%

Social security and welfare 4%

International affairs 3%

Judiciary 2%

Security and disaster management 1%

The classification is beneficial for agencies as

well. Typically, services provided by an agency

belong to a limited number of categories as each

agency has a scope of duties and responsibilities.

for example, Communication Regulatory Authority

services fit into three classes namely: establishing

laws, regulations, tariffs, and standards, validation

and qualification assessment, and monitoring, audit-

ing, and conducting trials (rca, 2018). It shows that

services are aligned with the organization’s goals

and responsibilities. On the other hand, Ports and

Maritime Organization services belong to all cate-

gories except service operator. In this case, probably

the organization is providing some irrelevant services.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

716

Figure 4: Delivering public services to citizens.

Table 2: Number of public services in each category.

Category Number

of services

Establishing laws, regulations, tar-

iffs, and standards

95

Validation and qualification assess-

ment

1243

Monitoring, auditing, and conduct-

ing trials

285

Enforcing the law 14

Registering public records 104

Publishing information, statistics,

and records

130

Providing funds and benefits 224

Training and cultivating culture 192

Infrastructure investment, develop-

ment, and maintenance

73

Service operator 234

All 2594

Classifying public services reflects the current

state of the government services. It assists the govern-

ment and IT managers in making informed judgments

and decisions and facilitates management.

Future work concerns deeper analysis of public

services to gain accurate information about the cur-

rent state of the e-government. In addition, another

direction for future work includes using public service

classification in ITIL implementation as we think that

the agencies can take a great advantage of using the

classification especially in service design phase.

6 CONCLUSION

This paper introduces ten categories for classifying e-

government services in Iran as a part of the national

BRM. Using this classification is a catalyst for mon-

itoring and verification of public services. This clas-

sification does not only help us to verify the services

but also benefit public agencies. In addition, making a

decision about the appropriate level of service granu-

larity will be easier. It should be noted that our experi-

ence with classifying public service shows that at first

identifying the service category was time-consuming

but by gaining more experience this process speeds

up.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Information Technology

Organization of Iran. We thank our colleagues from

SOEA lab. We would also like to thank Mr. Jahangard

for his kind support.

REFERENCES

(2018). Communications regulatory author-

ity (cra) of the i.r. of iran services.

https://www.cra.ir/Portal/View/Page.aspx?PageId=

a787c384-01f6-4ef5-a2dc-9fc74f4c9e0b&t=47.

(2018a). Iran e-government services mobile application.

https://mob.gov.ir/.

A Classification Taxonomy for Public Services in Iran

717

(2018b). Iran e-government services portal.

https://iran.gov.ir/.

Adams, M., Clasen, D., Haviland, P., Jimenez, Y., Lazar, K.,

Noon, R., Panaich, N., and Turner, M. (2014). World-

class ea: Business reference model (white paper).

Australian Government Information Management Office

(2011). Australian government architecture reference

models. www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/aga-

ref-models.pdf.

CIO Council (2013). Federal enterprise architecture frame-

work.

Deleu, R. and Clendon, J. (2015). Gea-nz v3.1

business reference model and taxonomy.

https://www.ict.govt.nz/assets/Guidance-and-

Resources/GEA-NZ-v3.1-Business-Reference-

Model-and-Taxonomy.pdf.

Fonseca, W. R. and Corr

ˆ

ea, P. L. (2014). Use of service pat-

terns as an approach to modelling of electronic gov-

ernment services. In Enterprise Interoperability VI,

pages 113–124. Springer.

Lankhorst, M. M. and Bayens, G. (2009). A service-

oriented reference architecture for e-government. Ad-

vances in Government Enterprise Architecture, pages

30–55.

Lee, Y.-J., Kwon, Y.-I., Shin, S., and Kim, E.-J. (2013).

Advancing government-wide enterprise architecture-

a meta-model approach. In Advanced Communication

Technology (ICACT), 2013 15th International Confer-

ence on, pages 886–892. IEEE.

Nazih, M. and Alaa, G. (2011). Generic service patterns for

web enabled public healthcare systems. In Next Gen-

eration Web Services Practices (NWeSP), 2011 7th In-

ternational Conference on, pages 274–279. IEEE.

Ojo, A., Janowski, T., and Estevez, E. (2012). Improving

government enterprise architecture practice–maturity

factor analysis. In System Science (HICSS), 2012 45th

Hawaii International Conference on, pages 4260–

4269. IEEE.

Saha, P. (2009). Architecting the connected government:

practices and innovations in singapore. In Proceed-

ings of the 3rd international conference on theory

and practice of electronic governance, pages 11–17.

ACM.

Saha, P. (2010). Enterprise architecture as platform for con-

nected government: Advancing the whole of govern-

ment enterprise architecture adoption with strategic

(systems) thinking.

Shams Aliee, F., Bagheriasl, R., Mahjoorian, A., Mobash-

eri, M., Hoseini, F., and Golpayegani, D. (2017). To-

wards a national enterprise architecture framework in

iran. In ICEIS 2017 - Proceedings of the 19th Interna-

tional Conference on Enterprise Information Systems,

Volume 3, Porto, Portugal, April 26-29, 2017, pages

448–453.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

718