Polycentric Climate Governance and the Amazon Tipping Point

Indigenous Climate Governance in Acre-Brazil and Ucayali-Peru

Fronika Claziena Agatha de Wit

Institute of Social Science, University of Lisbon, Av. Prof. Aníbal Bettencourt 9, Lisbon, Portugal

1 RESEARCH PROBLEM

Due to its high complexity and uncertainty, climate

change is an example of a ´wicked´ problem

(Incropera 2015); there is no silver bullet or one-

size-fits all solution. Next to the climate challenge,

we also face a need to feed an increasing world

population. Land use change for agricultural

expansion has facilitated meeting the increased need,

but it challenges the ecosystem´s capacity to

maintain biodiversity and regulate the climate (Foley

2005). The Earth System is facing boundaries to

high anthropogenic pressures and, in order to create

a safe operation space on earth, the Planetary

Boundary (PB) Framework has estimated nine

global boundaries (Rockstrom et al. 2009). Drawing

upon scientific research, the PB Framework

quantified seven of the boundaries and estimated

that the boundaries for climate change, biodiversity

loss and changes to the nitrogen cycle have already

been passed (Rockstrom et al. 2009). Although the

PB Framework, provides us with a “planetary

playing field”, critics have pointed to the

Framework´s missing “social dimension”: It

describes a safe, but not necessary a just operating

space (Raworth 2012). With the 17 Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015 at the

UN Summit, researchers updated the PB Framework

and placed it into the social context of the SDGs

(Steffen et al. 2015). However, they did not provide

pathways for just development inside the

boundaries.

Related to the PB Framework are the Tipping

Points: planetary thresholds that, when crossed, may

drastically change ecosystems or even lead to

collapse (Lenton et al. 2008). One of the global

tipping elements is the Amazon, where complex

interactions between local land-use change and

global emissions determine potential future

scenarios: forest dieback might turn the forest from

carbon sink to carbon emitter (Nepstad et al. 2008).

Modeling studies show that the Amazon is facing

two different tipping points, one related to global

climate change and one to local land-use change.

The first tipping point happens if the global

temperature increases with 3-4°C; The second if

more than 40% of the forest area is deforested

(Nobre & Borma 2009). Both threats may compound

each other and should therefore be considered

together when planning and implementing climate

policies in the Amazon (Betts et al. 2008).

Deforestation for agricultural purposes is one of

the main drivers of increased emissions and accounts

for three-quarters of all tropical deforestation

(Barker 2007). Reducing emissions from

deforestation, while at the same time keeping up

agricultural production, is a major challenge for

environmental governance. Top-down strategies fail

to align the diverse levels and sectors of government

and exclude local stakeholders from the process

(Ostrom et al. 2010). Nobel Prize winner Elinor

Ostrom introduced a bottom-up form of climate

governance with polycentric patterns (Ostrom et al.

2010). The concept of polycentric governance, a

form of multi-level governance, assumes multi-actor

and multi-sector decision-making under a general

system of rules leading to a productive arrangement.

It highlights the importance of vertical and

horizontal integration as well as learning-by-doing

for effective climate governance.

The future of the Amazon is a topic of global

concern: It sustains about 40% of the world's

remaining tropical rainforests, making it an

important provider of environmental services

(Fearnside 2008). In the recent past the region was

perceived as a “cowboy economy”, symbolic for its

illimitable natural resources and associated with

reckless, exploitative behavior (Boulding 1966).

Studies on the relationship between territory,

development and governance, have changed this

conceptualization of the Amazon as one big

homogenous green space (Becker 2005a). The

Amazon faces an exogenous and endogenous

current: the exogenous current sees the Amazon as a

source of natural resources for Brazilian and foreign

private sector actors, the endogenous current on the

other hand, represents the various local institutions

de Wit, F.

Polycentric Climate Governance and the Amazon Tipping Point.

In Doctoral Consortium (GISTAM 2018), pages 19-26

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

19

in the quest for a form of local development (Abdala

2015). Brazilian geographer Bertha Becker

introduces a new pathway for the Amazon that

strives towards a new development model with an

important role for the Amazonian people (Becker

2013). This PhD-project intends to answer the

question to what extend polycentric climate

governance with spatial justice, can prevent the

Amazon tipping point and lead to more inclusive

and just development.

2 OUTLINE OF OBJECTIVES

The study´s main objective is to analyze the

potentials and pitfalls of polycentric climate

governance towards new pathways for a safe and

just operating field in the Amazon. We look for site-

specific, dynamic forms of climate governance that

are able to provide a more effective response

towards the faced threat of the Amazon tipping

points. This PhD-thesis has four objectives, visually

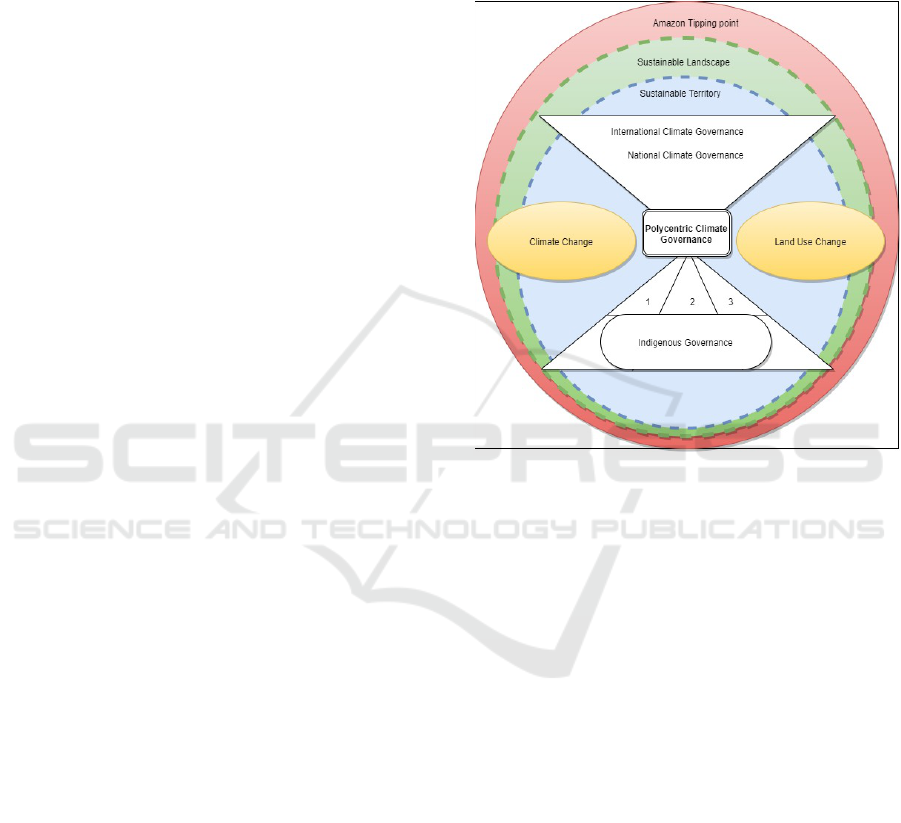

illustrated by Figure 1:

1.) To evaluate the impact of polycentric governance

on preventing the Amazon tipping point, by

analyzing vertical (multi-level) and horizontal

(multi-sector) policy and network integration and

coherence.

The red circle in Figure 1 represents the Amazon

tipping point that is related to global (orange circle:

Climate Change) and local factors (orange circle:

Land Use Change).

2.) To identify a territorial dimension of polycentric

climate governance in the Amazon that is sensitive

to spatial justice.

Climate governance in the Amazon entails

United Nations programs aimed at Reducing

Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation

(REDD). The REDD-discourse focuses on the

concept of “sustainable landscape”, such as a

watershed or ecological unit, rather than “sustainable

territory”, such as a local community (McCall 2016).

Figure 1 shows the different discourses with the

green circle (sustainable landscape) and blue circle

(sustainable territory).

3.) To assess bottom-up policy pathways for safe and

just development, involving local stakeholders.

Figure 1 shows two triangles that represent top-

down and bottom-up governance. The upside-down

triangle represents top-down policy pathways

(international and national level); the other triangle

stands for bottom-up governance (sub-national

level).

4.) To identify local (indigenous) ontologies and

epistemologies for safe and just development and

their incorporation in Amazon climate governance.

Figure 1 shows this study´s focus on indigenous

governance in the oval inside the triangle.

Figure 1: Theoretical framework of this research on

Polycentric Climate Governance, showing the Amazon

Tipping Point (red circle) and its two inter-related factors

Climate and Land Use Change (orange circles); its safe

(green circle) and just (blue circle) planetary boundary;

top-down and bottom-up climate governance (triangles).

This study has direct links with the 17

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and in

particular with SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), SDG

13 (climate action), SDG 15 (sustainable forest

management) and SDG 17 (global partnerships).

Governance must be a crucial part of the SDGs

(Biermann et al. 2014), and this study provides

examples of integrating bottom-up climate

governance into the goals.

3 STATE OF THE ART

Planetary boundaries are of great concern for policy-

making and require a restructuring of governance

arrangements (Folke et al. 2010). Decades of

international environmental conservation efforts

show that national governments alone cannot ensure

conservation; governing climate change is a multi-

DCGISTAM 2018 - Doctoral Consortium on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

20

level and multi-sector process that needs Multi-

Level Governance (MLG) (Ostrom et al. 2010). By

including social dimensions to climate change

adaptation, governance becomes more inclusive,

adding richness and value to the systems (Pelling

2011). Hooghe and Marks (2003) distinguish

between two types of MLG. Type I governance

(nested approach) shows clear vertical linkages

between governance levels with a central role for the

nation-state, whereas Type II governance

(polycentric approach) jurisdictions operate at

numerous territorial scales and are flexible rather

than durable (Hooghe & Marks 2003, p.237).

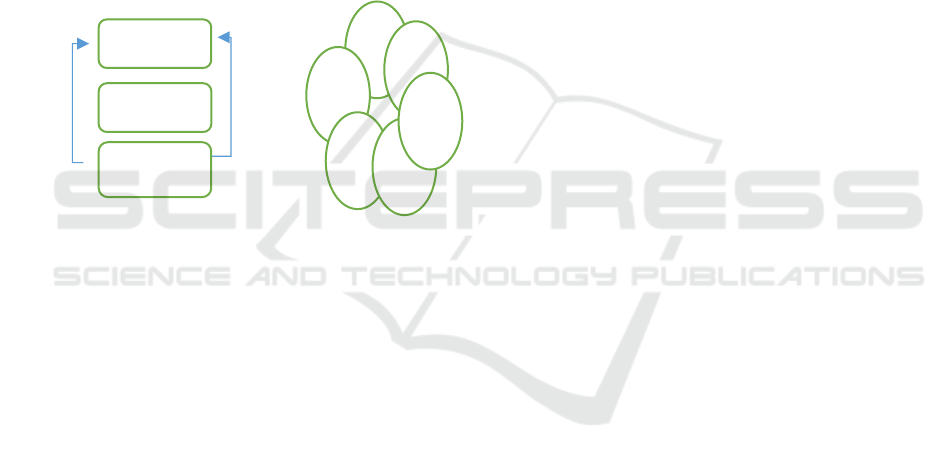

Bulkeley et al (2003) present the two types of MLG

structures, showing the top-down “Russian doll set

of nested jurisdictions” of Type I MLG and the

overlapping crosscutting jurisdictions as well as the

role of civil society in Type II MLG (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparing the structures of Type I-Nested

governance with the arrows representing direct

representation and transnational networks between local

government, national government and international

institutions and Type II-Polycentric governance, operating

at numerous territorial scales, involving transnational

networks (TN), place-based partnerships (PBP), civil

society (CS), subnational government (Sub), nation-state

(State), and supranational institutions (SI) (adapted from

Bulkeley et al, 2003).

The concept of ´polycentric governance´ is used

with different levels of precision, and different

conceptualizations of its vertical and horizontal

forms of differentiation (Dorsch & Flachsland

2017). An example of polycentric patterns for

climate governance are subnational governments

that drive policy change and self-organize into

transnational networks to commit to climate and

energy targets and organize policy transfer

(Hakelberg 2014; Urpelainen 2013; Bulkeley &

Betsill 2016; Hoffmann 2011). Another example is

climate change insurance, where fossil fuels are

insured, based on insurance principles of precaution,

risk assessment and risk sharing, public-private

oversight body (Spreng et al. 2016). Others have

analyzed new global actors, mechanisms, and

interrelations (Biermann & Pattberg 2012) and the

growth of transnational climate change governance

(Abbott 2012; Andonova et al. 2009; Bulkeley et al.

2003; Bulkeley & Betsill 2016).

Dorsch and Flachsland (2017) characterize four

main features of polycentric climate governance:

self-organization, site-specific conditions,

experimentation and learning and a strong emphasis

on trust, which can overcome cooperation dilemmas.

Experimentation and learning can lead to innovation

and flexible adaptation, as well as the production

and diffusion of knowledge and norms. A multi-

scale approach to the problem of climate change is

be more effective and encourages experimentation

and learning (Ostrom et al. 2010). Cole (2015)

shows how in a polycentric approach, the enhanced

direct communication of individuals positively

affects trust levels, which themselves substantially

determine levels of cooperation.

More recently, some authors have started

elaborating different attempts to actively manage

uncoordinated efforts to reduce such potential

inefficiencies, through linking or “orchestration” by

traditional actors such as international organizations

and committed states (Dorsch & Flachsland 2017).

Authors are questioning if the polycentric, multiple

level approach, is really going to lead to a cohesive

response to climate change (Aligica & Tarko 2012).

Strong free-rider incentives for some actors will very

likely continue to exist (Dorsch & Flachsland 2017).

Also, the costs and benefits of an increasingly

polycentric approach to climate mitigation

governance are difficult to estimate, when compared

to top-down approaches (Dorsch & Flachsland

2017). Taking into account a broader group of

potentially relevant actors who can contribute to the

goal of enhanced climate mitigation comes with a

high risk of uncoordinated, or even contradictory,

policies and actions (Dorsch & Flachsland 2017)

Research shows the benefits of the polycentric

approach in urban politics of climate change

(Bulkeley et al. 2014). However, it is crucial to

evaluate the impact and effectiveness of polycentric

governance more thoroughly .Jordan et al (2015)

critically discuss promising strands of the literature

on new, dynamic forms of climate governance, but

call for scientific and political efforts to strengthen

the understanding and effectiveness of these diverse

polycentric patterns. Making polycentric governance

effective requires ongoing research to refine, revise,

and adapt the regime’s rules and practices (Spreng et

al. 2016). In addition, it requires continuous

monitoring to ensure that implementation enables

International

National

I

Local

II

SI

State

Sub

CS

PBP

TN

Polycentric Climate Governance and the Amazon Tipping Point

21

and demands constructive interactions to make the

polycentric governance work properly.

3.1 Moving Beyond

Political science scholars have done extensive top-

down research on new forms of climate governance

and polycentricity in the developed world (Rayner &

Jordan 2013; Jordan et al. 2015; Spreng et al. 2016;

Termeer et al. 2011; Bulkeley et al. 2003; Bulkeley

& Betsill 2016). However, there is a lack of more

people-centered research, to empower the poorest

people and countries in their efforts to fight climate

change. Climate Justice links human rights and

development to achieve a human-centered approach,

safeguarding the rights of the most vulnerable and

sharing the burdens and benefits of climate change

and its resolution equitably and fairly (MRF 2015).

This study will move beyond the current studies of

polycentric governance, and will combine a

geographical and anthropological perspective, for

policy pathways towards spatial climate justice in

the Amazon.

In the analysis of bottom-up pathways for the

Amazon, we will link climate governance with the

concept of territoriality. Research points to the

importance of new emerging territorialities at

different scales, which are not only putting in doubt

the primacy of the macro-region for planning, but

also the nation-state as the only source of power

(Becker 2010). The Amazon´s regional

heterogeneity and bio-socio-diversity represent new

territorialities resistant to expropriation, such as

indigenous people, rubber tappers or family farmers.

For diverse reasons, these actors have the presence

of the state government as a first demand,

highlighting the relevance of sub-regionalization

(Becker 2005b). New Amazonian governance

experiences show the involvement of populations of

different ethnic and geographical origins, using

various social and political productive structures, as

well as diverse partnerships (Becker 2010).

Although its sustainability is still unknown, we can

already point to diverse potentialities, such as

Extractive Reserves (RESEX), Family Farming

Projects, and most important, Indigenous Lands and

its People that have become effective regional actors

(Becker 2010). In her last work "A Urbe

Amazônida", Becker uses the concept of

´sustainable territory´ instead of ´sustainable

landscape´ and thereby stresses the importance of

the different social actors living in the Amazon

(Vieira & et. al 2014).

4 METHODOLOGY

This research consists of five tasks and each task

will lead to a scientific paper on Polycentric Climate

Governance (to be submitted to WoS and Scopus

indexed journals). For a description of the five

tasks/articles and their methods, go to section 4.2.

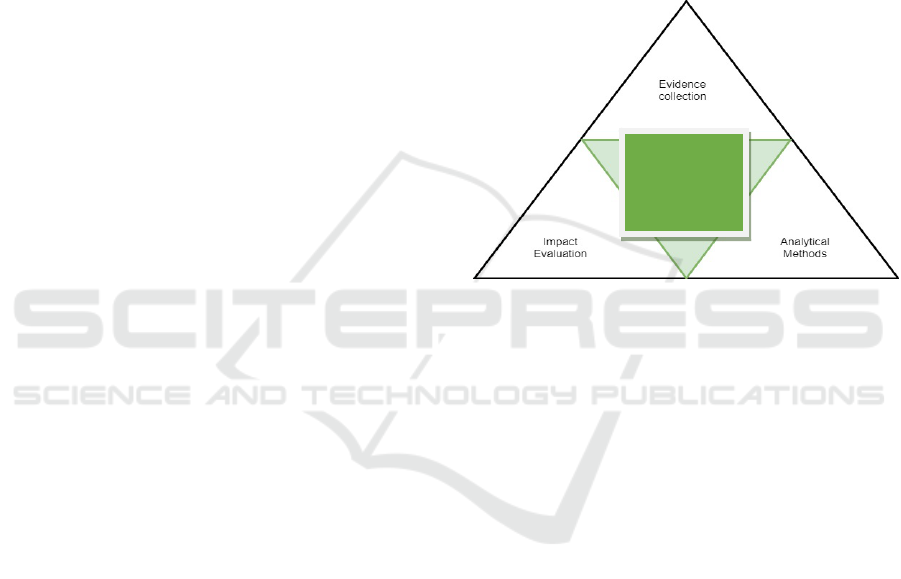

In order to assess polycentric climate

governance in the Amazon, I will use a triangulation

of both qualitative and quantitative methods: a

combination of evidence collection, impact

evaluation and analytical methods (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: This research´s methodology to assess

polycentric climate governance in the Amazon is based on

a triangulation of qualitative and quantitative methods.

The nine countries that make up the Amazon

have very diverse social, political, economic and

institutional characteristics, which complicates the

evaluation of its regional environmental governance

strategies. That is why we will assess polycentric

climate governance by looking at two case studies.

The case study method enables us to capture the

complex institutional context and gain in-depth

understanding of interactions and perspectives of

different stakeholders to be able to interpret a

particular case (Yin & Heald 2016). I will shortly

describe the chosen case studies in section 4.1.

4.1 Case Studies

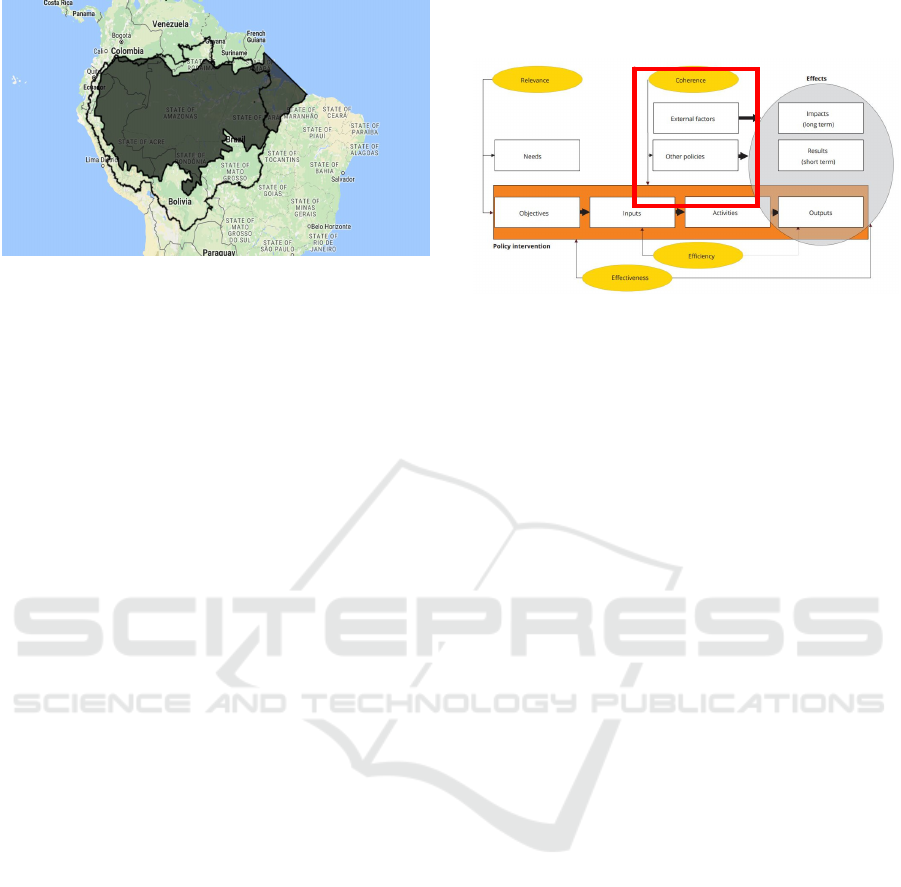

To grasp more of the Amazon´s geopolitical

diversity, we will assess climate governance in the

two countries that hold the largest land area of the

Amazon basin, Brazil and Peru. Brazil holds

approximately 65% of the Amazon, followed by the

Peruvian share that makes up for 10% of the basin

(Global Forest Atlas 2018) (see Figure 4).

Polycentric

Climate

Governance

DCGISTAM 2018 - Doctoral Consortium on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

22

Figure 4: The Amazon is shared by nine South American

countries, with its largest parts in Brazil and Peru. The

region can be classified as the Amazon river basin (outer

line) and Amazon biome (shaded polygon).

Out of Peru´s 24 regional departments, five are

part of the Peruvian selva (Amazon). The Peruvian

department that will serve as our case study for

polycentric climate governance in the Amazon is

Ucayali. Ucayali is an interesting case study,

because research shows the department´s land

conflicts with its indigenous populations and climate

governance structures where untitled communities

are ´hidden´ under investment opportunities(Leal

Pereira et al. 2015).

The Brazilian State of Acre, situated on the

border with Bolivia and Peru, is one of Brazil´s nine

Amazon States. Between 2011 and 2016, I lived in

Acre, and could observe the state´s development of

its State System of Incentives for Environmental

Services: One of the world´s most advanced

statewide programs in low-emission rural

development (Stickler 2014). The State´s

experiments with forest-based development and

forest citizenship have led to a comprehensive

approach that links policies across sectors, involves

civil society and continuously builds institutional

capacity (Schminck et al. 2014).

4.2 General Protocol

In this section, I will provide a short overview of the

five tasks/articles of this PhD-thesis.

4.2.1 Climate Governance and the Future of

the Amazon

Here I analyze the combined impact of global

climate change and local land use change on the

Amazon, by looking at primary data and evaluating

the coherence of climate policies and programs for

the Amazon, using the Climate Policy Evaluation

Framework (EEA 2016) and the Policy Coherence

Tool (Nilsson et al. 2012).

Figure 5: The focus of this article is the coherence of

climate measures in the Amazon, making use of the

Climate Policy Evaluation Framework of the European

Environmental Agency (EEA 2016).

Methods:

Analyzing climate projections for the Amazon

by running simulations from CMIP5

(Coupled Model Intercomparison Project)

models under RCP4.5, RCP6.0, and RCP8.5.

Observing historic change in vegetation cover

via the Normalized Difference Vegetation

Index (NDVI) for the Amazon Biome.

Evaluating the coherence of international,

national and state climate policies using the

European Environmental Agency´s Climate

Policy Evaluation Framework (EEA 2016)

(see Figure 5).

4.2.2 Polycentricity and Territoriality

This article combines the concepts of polycentric

climate governance and spatial justice. Hereby, I aim

to look for site-specific dynamic forms of climate

governance that are able to provide a more effective

response towards the faced threats.

Methods:

Conducting a systematic literature review on

climate governance and spatial justice.

Mapping all indigenous territories and

protected areas in the Brazilian and Peruvian

Amazon and their jurisdictional status, with

the use of Geographical Information Systems

(ArcGIS).

Crossing data on deforestation in the Amazon

(making use of Brazil´s PRODES

deforestation monitoring by satellite) with

spatial planning data in the Amazon

Polycentric Climate Governance and the Amazon Tipping Point

23

4.2.3 Environmental Governance and

Climate Justice

This article will make use of the richness of

available case material on Climate Governance in

the Amazon and use the Case Survey Methodology

(Larsson et al. 1993) to conduct a meta-analysis on

“Amazon Governance” in order to assess its social

and spatial implications.

Methods:

• Selection of cases with a WoS and Science-

Direct search of peer-reviewed articles

related to “Amazon Governance”.

• Coding of selected cases using MaxQDA

coding software.

• Statistical analysis of coded information

using R.

4.2.4 Climate Governance and Indigenous

Ontologies and Epistemologies

This article will focus on the role of local

(indigenous) perspectives and knowledge related to

climate governance in Acre-Brazil and Ucayali-

Peru.

Methods:

Literature review on Indigenous Epistemologies

and Ontologies towards environmental

governance.

Participant observation in the case study area in

April 2018 and August to October 2018.

Semi-structured interviews and focus groups

with local stakeholders and indigenous

leaders in case study area.

Content analysis of the data gathered using

MaxQDA software-program

4.2.5 Climate Policy Network Analysis

This article will focus on climate policy networks in

Acre-Brazil and Ucayali-Peru, using social network

methodologies (Borgatti et al. 2009).

Methods:

Climate policy data and information collection

for Acre-Brazil and Ucayali-Peru

Semi-structured interviews and questionnaires

with actors involved in climate governance in

the study area.

Policy Network Analysis on cooperation and

information sharing, using the software-

program Gephi.

5 EXPECTED OUTCOME

With this study, I expect to provide theoretical

advances to the concept of polycentric climate

change. By looking at bottom-up experiences in the

Amazon, this study will challenge the existing body

of knowledge on the potentials and pitfalls of

polycentric governance It does not only add the

anthropological and geographical perspective to the

discussion, but also sheds a light on the link between

climate governance and climate justice. In addition,

this PhD-thesis adds the “Epistemologies of the

South” (Escobar 2016) – local (indigenous)

knowledge and strategies – towards a more just and

inclusive way of development. It highlights that the

Amazon does not only have a high biological

diversity, but also a high social diversity that needs

to be incorporated in development policy and

planning. The Planetary Boundaries framework

focusses on the ecological limits of our planet,

however thereby it creates another limit; the

boundary between indigenous knowledge and

scientific knowledge. The basis of Indigenous

knowledge are cosmologies that differ from the

Western classic distinction between Nature and

Culture (Coleman 1998). Their perspectives arise

from geographical features mutual recognition,

active communication amongst people, animals,

plants, spirits and the dead conceived as actors in the

same socio-cosmological networks (Viveiros De

Castro 2004; de Castro 1998; Schwartzman et al.

2013). This study aims to look at ways to

incorporate the Amerindian cosmology into climate

adaptation strategies in specific and climate

governance in general.

6 STAGE OF THE RESEARCH

This PhD-research is part of the Doctoral Program in

Climate Change and Sustainable Development

Policies of the University of Lisbon in Portugal. The

research has received funding from the Portuguese

Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT),

which started in September 2017. It is a three-year-

research and entails two fieldwork trips to the study

area: one fieldwork trip in April 2018 and one from

September to November 2018. As this research is in

its initial stage, its current focus on the revision of

literature, testing of methods and initial data

collection.

DCGISTAM 2018 - Doctoral Consortium on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

24

REFERENCES

Abbott, K. W., 2012. The transnational regime complex

for climate change. Environment and Planning C:

Government and Policy, 30(4), pp.571–590.

Abdala, G. (WWF), 2015. The Brazilian Amazon :

challenges facing an effective policy, Brasilia.

Aligica, P. D. & Tarko, V., 2012. Polycentricity: From

Polanyi to Ostrom, and Beyond. Governance, 25(2),

pp.237–262.

Andonova, L. B., Betsill, M.M. & Bulkeley, H., 2009.

Transnational Climate Governance. Global

Environmental Politics, 9(2), pp.52–73.

Barker, T., 2007. Climate Change 2007 : An Assessment

of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Change, 446(November), pp.12–17.

Becker, B. K., 2013. A urbe amazônida : a floresta e a

cidade, Garamond.

Becker, B. K., 2005a. Geopolítica da Amazônia. Estudos

Avançados, 19(53), pp.71–86.

Becker, B. K., 2005b. Geopolítica da Amazônia. Estudos

Avançados, 19(53), pp.71–86.

Becker, B. K., 2010. Novas territorialidades na Amazônia:

desafio às políticas públicas New territorialities in the

Amazon: a challenge to public policies. Bol. Mus.

Para. Emílio Goeldi. Cienc. Hum, (1), pp.17–23.

Betts, R. A., Malhi, Y. & Roberts, J. T., 2008. The future

of the Amazon: new perspectives from climate,

ecosystem and social sciences. Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological

Sciences, 363(1498), pp.1729–1735.

Biermann, F. et al., 2014. Integrating Governance into the

Sustainable Development Goals. POST2015/UNU-IAS

Policy Brief, (3).

Biermann, F. & Pattberg, P., 2012. Global environmental

governance reconsidered,

Borgatti, S. P. et al., 2009. Network analysis in the social

sciences. Science, 323(5916), pp.892–895.

Boulding, K. E., 1966. The Economics of the Coming

Spaceship Earth. Environmental Quality Issues in a

Growing Economy, pp.1–8.

Bulkeley, H. et al., 2003. Environmental Governance and

Transnational Municipal Networks in Europe. Journal

of Environmental Policy & Planning, 5(3), pp.235–

254.

Bulkeley, H. & Betsill, M., 2016. Rethinking Sustainable

Cities : Multilevel Governance and the “ Urban ”

Politics of Climate Change. , 4016(May), pp.37–41.

Bulkeley, H., Edwards, G.A.S. & Fuller, S., 2014.

Contesting climate justice in the city: Examining

politics and practice in urban climate change

experiments. Global Environmental Change, 25(1),

pp.31–40.

Cole, D. H. & Cole, D.H., 2015. Advantages of a

Polycentric Approach to Climate Change Policy

change policy.

Coleman, S., 1998. Nature and Society. Anthropological

Perspectives. Edited by Philippe Descola & Gisli

Pálsson. Pp 310.(Routledge, London, 1996.).

Dorsch, M. J. & Flachsland, C., 2017. A Polycentric

Approach to Global Climate Governance. , (May),

pp.45–64.

EEA, 2016. Environment and climate policy evaluation,

Copenhagen. Available at: http://www.eea.europa.eu/

publications/environment-and-climate-policy-evaluati

on.

Escobar, A., 2016. Thinking-feeling with the earth:

Territorial struggles and the ontological dimension of

the epistemologies of the south. AIBR Revista de

Antropologia Iberoamericana, 11(1), pp.11–32.

Fearnside, P. M., 2008. Amazon forest maintenance as a

source of environmental services. Anais da Academia

Brasileira de Ciencias, 80(1), pp.101–114.

Foley, J. A., 2005. Global Consequences of Land Use.

Science, 309(5734), pp.570–574.

Folke, C. et al., 2010. Resilience thinking: Integrating

resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology

and Society, 15(4).

Global Forest Atlas, 2018. The Amazon Basin Forest.

Available at: https://globalforestatlas.yale.edu/region/

amazon [Accessed February 8, 2018].

Hakelberg, L., 2014. Governance by Diffusion:

Transnational Municipal Networks and the Spread of

Local Climate Strategies in Europe. Global

Environmental Politics, 14(1), pp.107–129.

Hoffmann, M. J., 2011. Climate Governance at the

Crossroads: Experimenting with a Global Response

after Kyoto,

Hooghe, L. & Marks, G., 2003. Unraveling the Central

State, but How? Types of Multi-level Governance.

American Political Science Review, 97(2), pp.233–

243.

Incropera, F. P., 2015. Climate change : a wicked

problem : complexity and uncertainty at the

intersection of science, economics, politics and human

behavior, Cambridge University Press.

Jordan, A.J. et al., 2015. Emergence of polycentric climate

governance and its future prospects. Nature Climate

Change, 5(11), pp.977–982. .

Larsson, R. et al., 1993. Case Survey Methodology:

Quantitative Analysis of Patterns Across Case Studies.

Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), pp.1515–

1546.

Leal Pereira, D. et al., 2015. Journal of Latin American

Geography Ideas cambiantes sobre territorio, recursos

y redes políticas en la Amazonía indígena: un estudio

de caso sobre Perú.

Lenton, T. M. et al., 2008. Tipping elements in the Earth’s

climate system. Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences, 105(6), pp.1786–1793.

McCall, M. K., 2016. Beyond “Landscape” in REDD+:

The Imperative for “Territory.” World Development,

85, pp.58–72.

MRF, 2015. Principles of Climate Justice. Mary Robinson

Foundation – Climate Justice, p.3. Available at:

http://www.mrfcj.org/pdf/Principles-of-Climate-

Justice.pdf.

Nepstad, D. C. et al., 2008. Interactions among Amazon

land use, forests and climate: prospects for a near-term

Polycentric Climate Governance and the Amazon Tipping Point

25

forest tipping point. Philosophical transactions of the

Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological

sciences, 363(1498), pp.1737–46. Available at:

Nilsson, M. et al., 2012. Understanding Policy Coherence:

Analytical Framework and Examples of Sector-

Environment Policy Interactions in the EU.

Environmental Policy and Governance, 22(6),

pp.395–423.

Nobre, C. A. & Borma, L. D. S., 2009. “Tipping points”

for the Amazon forest. Current Opinion in

Environmental Sustainability, 1(1), pp.28–36.

Ostrom, E. et al., 2010. American Economic Association

Beyond Markets and States : Polycentric Governance

of Complex Economic Systems Beyond Markets and

States : Polycentric Governance of Complex

Economic Systems *. American Economic Review,

100(3), pp.641–672.

Pelling, M., 2011. Adaptation to Climate Change from

resilience to tranformation,

Raworth, K., 2012. A Safe and Just Space For Humanity:

Can we live within the Doughnut? Nature, 461, pp.1–

26.

Rayner, T. & Jordan, A., 2013. The European Union: The

polycentric climate policy leader? Wiley Interdiscipli-

nary Reviews: Climate Change, 4(2), pp.75–90.

Rockstrom, J. et al., 2009. Planetary boundaries:

Exploring the safe operating space for humanity.

Ecology and Society, 14(2).

Schminck, M. et al., 2014. Forest Citizenship in Acre ,

Brazil. In Forests under pressure : Local responses to

global issues. IUFRO World Series, pp. 31–47.

Schwartzman, S. et al., 2013. The natural and social

history of the indigenous lands and protected areas

corridor of the Xingu River basin. Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological

Sciences, 368(1619).

Spreng, C. P., Sovacool, B. K. & Spreng, D., 2016. All

hands on deck : polycentric governance for climate

change insurance. Climatic Change, pp.129–140.

Steffen, W. et al., 2015. Article: Planetary Boundaries:

Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet.

Journal of Education for Sustainable Development,

9(2), pp.235–235.

Stickler, C., 2014. Fostering Low-Emission Rural

Development From the Ground Up. , p.36p. Available

at: http://earthinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/

2014/12/Fostering_Tropical_LED-R.pdf [Accessed

June 2, 2017].

Termeer, C. et al., 2011. The regional governance of

climate adaptation: A framework for developing

legitimate, effective, and resilient governance

arrangements. Climate Law, 2(2), pp.159–179.

Urpelainen, J., 2013. A model of dynamic climate

governance: Dream big, win small. International

Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and

Economics, 13(2), pp.107–125.

Vieira, I. C. G. & et. al, 2014. Bertha Becker e a

Amazônia.

Revista Bibliográfica de Geografía y

Ciencias Sociales, Serie Documental de Geo Crítica,

XIX(1103 (4)).

Viveiros De Castro, E., 2004. Perspectival anthropology

and the method of controlled equivocation. Tipiti:

Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of

Lowland South America, 2(1), pp.2–22.

Yin, R. K. & Heald, K. A., 2016. Using the case survey

method to analyze policy studies. Sage Publications ,

Inc . on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of

Management , Cornell University, 20(3), pp.371–381.

DCGISTAM 2018 - Doctoral Consortium on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management

26