The Users' Perspective on Autonomous Driving

A Comparative Analysis of Partworth Utilities

Christina Pakusch

1

, Gunnar Stevens

1,2

, Paul Bossauer

1

and Tobias Weber

1

1

Department of Management Sciences, Bonn-Rhein-Sieg University, Sankt Augustin, Germany

2

Department of Information Systems, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany

Keywords: Self-driving Cars, Travel Mode Choice, User Acceptance, Relative Added Value, Partworth Utilities.

Abstract: Digitisation has brought a major upheaval to the mobility sector, and in the future, self-driving cars will prob-

ably be one of the transport modes. This study extends transport and user acceptance research by analysing in

greater depth how the new modes of autonomous private cars, autonomous carsharing and autonomous taxis

fit into the existing traffic mix from today's perspective. It focuses on accounting for relative added value. For

this purpose, user preference theory was used as a base for an online survey (n=172) on the relative added

value of the new autonomous traffic modes. Results show that users see advantages in the autonomous modes

for driving comfort and time utilization whereas, in comparison to conventional cars, in many other areas –

especially in terms of driving pleasure and control – they see no advantages or even relative disadvantages.

Compared to public transport, the autonomous modes offer added values in almost all characteristics. This

analysis at the partworth level provides a more detailed explanation for user acceptance of automated driving.

1 INTRODUCTION

Self-driving vehicles (SAE International, 2016) rep-

resent a technological leap forward that can offer so-

lutions to current traffic problems and dramatically

change the way people deal with mobility (Howard

and Dai, 2014; Piccinini et al., 2016). For some years,

fully automated vehicles have been tested in several

pilot projects (Nordhoff, 2014). The leading automo-

tive manufacturers and IT companies in the autono-

mous driving sector assume that full automation

could be ready for series production within the next

five to ten years. Experts expect driverless cars to re-

duce the number of accidents and traffic problems as

well as improve the efficiency of traffic flow

(Fagnant et al., 2015; Kyriakidis et al., 2015; Krueger

et al., 2016). Automated driving technology will also

create new, innovative business models such as vehi-

cle-on-demand (Fagnant et al., 2015; Pakusch et al.,

2016). Additionally, mobility services such as self-

driving taxis or autonomous carsharing could espe-

cially benefit from the self-driving technology: lower

personnel costs mean that driverless taxis can operate

much cheaper (Fagnant et al., 2015), and fully auto-

mated carsharing promises improvements in availa-

bility as the car comes to the user instead of vice versa

(Krueger et al., 2016). In this context, researchers see

a strong convergence of taxi and carsharing (Pakusch

et al., 2016). Various authors expect a significant re-

duction in the number of private cars through

strengthening usage-based mobility services

(Bunghez, 2015; Fagnant et al., 2015; Pakusch et al.,

2016). To gain a better understanding of user ac-

ceptance and to be able to better predict future

changes in mobility behavior due to new autonomous

modes of transport, we performed a study that exam-

ines autonomous travel modes and compares them to

existing modes on the basis of their respective char-

acteristics.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 Travel Mode Choice

To satisfy the human need for mobility (Verplanken

et al., 1994), various travel modes are available to the

user. From the various alternatives, the user chooses

the one that has a relative, often subjectively per-

ceived advantage over the others and thus maximizes

his or her personal benefit (McFadden, 2000). In ad-

dition to user-related and external influencing factors,

Pakusch, C., Stevens, G., Bossauer, P. and Weber, T.

The Users’ Perspective on Autonomous Driving - A Comparative Analysis of Partworth Utilities.

DOI: 10.5220/0006843201390146

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2018) - Volume 1: DCNET, ICE-B, OPTICS, SIGMAP and WINSYS, pages 139-146

ISBN: 978-989-758-319-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

139

product-related influencing variables play a major

role. According to Lancaster (1966), it is not the prod-

uct as a whole but its special characteristics that pro-

vide consumers with a benefit, the so-called part-

worth utilities. In the past, in addition to demo-

graphic, socio-economic, psychographic, geograph-

ical, and situational factors, a number of product-spe-

cific characteristics could be identified that influence

travel mode choice. Those studies come to different

conclusions regarding the ranking of those factors,

but they show that travel time, travel costs, and relia-

bility play a decisive role (Ponnuswamy and Anan-

tharajan, 1993; Johansson et al., 2004; Ding and

Zhang, 2016; Krueger et al., 2016). Further studies

such as that by Steg (2003) have analyzed the charac-

teristics of passenger cars and public transport as the

most frequently used travel modes from a user's point

of view. The ratings reflect the users’ usage patterns

by clearly showing that the car is rated better than

public transport in many respects – e.g. in terms of

convenience, independence, flexibility, flexibility,

driving comfort, speed and reliability.

2.2 User Acceptance of Autonomous

Vehicles

The transformative advantages of the self-driving

technology can only be realized if the majority of us-

ers accept self-driving cars (Howard and Dai, 2014).

Researchers have recently devoted themselves to the

topic of user acceptance. Their studies show that most

people have a positive attitude towards autonomic

driving and can imagine buying and/or using autono-

mous cars (Payre et al., 2014; Rödel et al., 2014;

Schoettle and Sivak, 2014). Thus, many respondents

gave a positive opinion on the technology and had op-

timistic expectations of its benefits (Schoettle and Si-

vak, 2014). Users see added value in improved road

safety, a more efficient traffic flow (Howard and Dai,

2014; Eimler and Geisler, 2015; Zmud et al., 2016),

and the convenience of not having to find parking

spaces and of better use of time while driving (How-

ard and Dai, 2014; Pakusch et al., 2016). At the top of

the advantages’ list, users can imagine autonomous

driving for driving on the motorway, in traffic jams,

and for automatic parking (Payre et al., 2014). At the

same time, the studies report on respondents’ con-

cerns: they fear software hacking and abuse and are

concerned about legal issues, security and reliability

of technology (Schoettle and Sivak, 2014; Kyriakidis

et al., 2015). Many respondents think that humans are

the better driver (Eimler and Geisler, 2015) and are

afraid of handing over control to technology (Howard

and Dai, 2014). From the users’ point of view, the

high acquisition and operating costs (Howard and

Dai, 2014; Eimler and Geisler, 2015) one expects

from autonomous vehicles and the loss of driving

pleasure associated with eliminating the driving task

(Nordhoff, 2014; Eimler and Geisler, 2015) speak

against their use.

Since new modes of transport such as autonomous

private cars, autonomous taxis or autonomous car-

sharing could extend the options for choosing a travel

mode, the question arises as to which travel mode us-

ers prefer and how this choice will change mobility

behaviour as a whole. Although there are many ac-

ceptance studies on autonomous driving, these stud-

ies generally view the autonomous car in isolation. To

our knowledge, transport mode selection analyses

have so far neither included the new modes nor com-

pared these with existing modes of transport. In a pre-

vious complete pair comparison study, we have there-

fore allowed users to choose between the current traf-

fic modes car, public transport, carsharing and the

new modes autonomous car and autonomous carshar-

ing (Pakusch et al., 2018). The results showed that,

from a user's perspective, the autonomous modes of

transport are significantly better than public transport,

while they are almost identical or worse than conven-

tional passenger cars. However, the question re-

mained as to what exactly was the reason for the par-

ticipants’ choices – in which factors they see relative

advantages or disadvantages of the respective modes

of transport. Therefore, this follow-up study analyses

the partworth utilities to obtain more precise infor-

mation on the composition of user acceptance. The

central research questions are

1. How does the decision in favour of or against a

travel mode relate to the relative overall benefit?

2. What relative partworth utilities do automated

travel modes offer?

3 METHODOLOGY

A two-stage survey was conducted to answer the re-

search questions carried out in Germany. In a qualita-

tive preliminary study, the criteria identified in the lit-

erature with regard to their relevance for the new

modes of transport were verified and adapted. To this

end, ten qualitative interviews were conducted in

which the interviewees were asked to assign charac-

teristics to both traditional and new modes of

transport and to explain their relevance. Based on this

preliminary study, a quantitative questionnaire was

created.

The questionnaire began with a comparison of the

ICE-B 2018 - International Conference on e-Business

140

traditional car with the autonomous private car, the

autonomous carsharing and the autonomous taxi. The

participants were asked to identify advantages and

disadvantages of the new modes in relation to the con-

ventional car with respect to 13 characteristics: driv-

ing time, waiting time, availability, flexibility, driv-

ing pleasure, driving comfort, ease of use, control of

the vehicle, safety, transport of objects, reliability,

costs and time utilization. Similarly, public transport

was compared with autonomous travel modes. Subse-

quently, respondents should indicate which travel

mode they would use or own regularly in the future.

Traditional and automated travel modes were availa-

ble. Finally, demographic data and information on

current mobility behaviour were collected.

A total of 172 people took part in the survey, 49%

of whom were female. The age range was 17 to 79

years (average 35.6). 64.7% lived (rather) urban, the

other 35.3% (rather) rural. Almost all participants

(95%) had a driving licence and 80% owned a car. Of

those surveyed, 71% were employed, 26% were pu-

pils or students and 3% were retired. About 63% of

respondents used the car as their main travel mode

and 20% used public transport.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Relative Partworth Utilities

Compared to Private Passenger

Cars

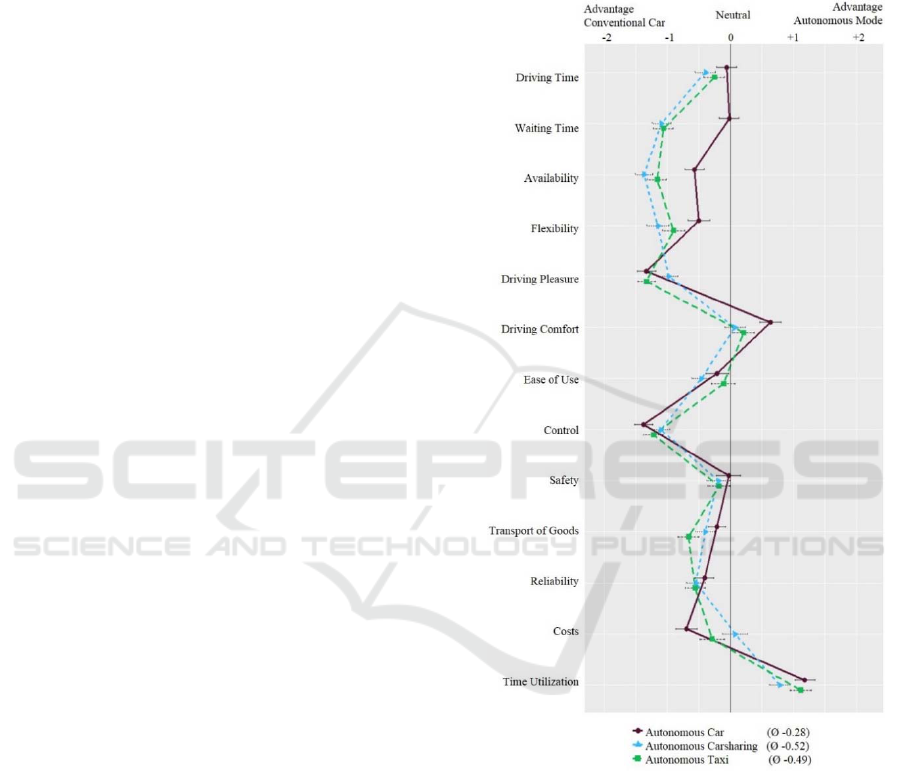

Figure 1 shows the participants’ subjective evaluation

of the individual partial utility utilities. From the re-

spondents' perspectives, the automated modes only

have advantages over traditional cars in terms of driv-

ing comfort and the use of time during driving. In all

other characteristics, the participants saw minor ad-

vantages for the traditional car in terms of driving

pleasure and control. With an (unweighted) average

of -0.28 for the autonomous car, -0.52 for autono-

mous carsharing and-0.49 for autonomous taxis, the

direct comparison showed the relative advantage of

traditional cars in each case: users would be expected

to go for those when having the choice.

In the following, we investigate in more detail

some of the prominent characteristics and reflect on

why the participants came to their assessments.

Autonomous vehicles offer greater driving com-

fort and greater time saving than traditional cars. Both

benefits are closely linked. Driving comfort is a mul-

tidimensional construct under which almost every

user understands something different (Gorr, 1997). It

includes coziness, comfort, and psychological

hygiene. These characteristics are judged negatively

if a travel mode must be shared with many others (ex-

ternal people) (especially public transport; Knapp,

2015). Autonomous modes of transport offer not only

the private space and comfort of a private car but also

the advantages of public transport.

Figure 1: Comparative assessment of autonomous travel

modes and the conventional car. (n=172, confidence inter-

val = 95%).

The use of time while driving a traditional car is

limited to passive activities such as listening to the

radio or making telephone calls. Because the driving

task is eliminated, self-driving technology makes it

possible to make better use of time in the car (Cy-

ganski et al., 2015). This levels off one of the ad-

vantages of public transport because the driver be-

comes a passenger (Pakusch and Bossauer, 2017). For

this reason, the attested added value in the use of time

for the autonomous car is in line with expectations.

The Users’ Perspective on Autonomous Driving - A Comparative Analysis of Partworth Utilities

141

However, it is surprising that the partial benefits of

time utilization for autonomous carsharing and taxis

are not as high as for autonomous cars. One explana-

tion could be that the private car seems to be more

individualizable so that the time can be used more ef-

fectively than e.g. in a non-private taxi.

In terms of driving pleasure and control, the tradi-

tional car offers significant relative added value over

autonomous modes of transport. This result confirms

the results of studies such as those by Nordhoff

(2014) or Eimler and Geisler (2015), which show that

some respondents fear that automating the car will re-

duce driving pleasure. Driving pleasure for the user

arises from the satisfaction of a personal desire for

nerve-racking thrills by risky driving styles when ac-

tively driving a vehicle. Due to the necessity of active

control, the car does indeed offer users a higher po-

tential for much more driving pleasure than modes

where the user does not actively control. The survey

confirms this assessment: The participants see a clear

added value for driving pleasure in the classic car

compared to all driverless modes. Active steering is

closely linked to control over the vehicle, which also

encompasses the entire physical and organizational

power over a travel mode and is of great importance

to users (Howard and Dai, 2014; Eimler and Geisler,

2015).

Waiting time, reliability, availability and flexibil-

ity are disadvantageous in all autonomous modes

compared to the classic car but more so in autono-

mous vehicle-on-demand services. In the case of au-

tonomous carsharing and taxis, the waiting time is

evaluated significantly worse than in the case of car

variants. This result is not surprising since, from the

moment a user is ready to drive and places an order

for autonomous taxi/carsharing, a waiting time can

arise until the actual start of the journey if the vehicle

has to reach the passenger's location.

The neutral evaluation of the waiting time for the

autonomous private car was to be expected. However,

an explanation is required as to why the assessment

of flexibility/independence and availability is signifi-

cantly lower for the autonomous version of the car

than for the traditional one. Here, the criteria also

seem to depend on reliability. The poor evaluation of

reliability can probably be attributed to the novelty of

the technology that users are still inexperienced with

and in which they do not yet trust. Participants in pre-

vious studies expressed concerns that the technology

could fail (Schoettle and Sivak, 2014; Kyriakidis et

al., 2015). These concerns would explain why it is be-

lieved that autonomous cars are not equally available

and flexible in every situation.

Model simulations assume that data-driven con-

trol, automatic relocation and automatic retrieval

greatly increase the availability, especially compared

to today's carsharing, so that the user has to wait on

average less than one minute (Fagnant et al., 2015).

Users usually lack such knowledge and thus appar-

ently lack the confidence that quick availability can

be guaranteed (e.g. if vehicles are occupied or not in

the immediate vicinity), so that the rating is lower

than with their own cars. The private car on the door-

step creates a feeling of flexibility and independence,

which apparently cannot be achieved in the same way

by a mobility service provider – even with full auto-

mation. The flexibility also includes free and autono-

mous time and route planning. The fully automated

system actually makes the car even more flexible

since autonomous cars can, for example, pick up us-

ers directly in front of the door, drop them off at their

destination, and then park on their own. However, the

survey shows that the traditional car is rated better.

One explanation is that flexibility/independence does

not only include flexible time and route planning, but

also, from the user's point of view, physical control of

the vehicle and freedom over driving style and spon-

taneous decisions (sudden stop or change of direc-

tion). Here, the fear that autonomous technology may

limit users in their own (ad-hoc) decisions may play

a role. Thus, the perceived loss of control (see above)

also has a negative effect on independence and flexi-

bility.

In terms of costs, respondents also saw a disad-

vantage – especially in private autonomous cars. In

contrast to the use-based modes, the latter would not

only incur usage-dependent variable costs but also

fixed costs of ownership. In addition, users also ex-

pect higher start-up costs due to the self-driving tech-

nology as well as higher operating costs due to the

additional technology, which may cause new faults

and require more maintenance (Howard and Dai,

2014; Eimler and Geisler 2015).

Due to the fully-automated system, there are im-

provements especially in carsharing, if the user does

not have to carry the luggage to the pick-up station.

Although it could be assumed that the transport with

similar fully automated vehicles, which always pick

up the user at the front door, is equally possible, the

interviewees still saw a slight advantage in the classic

car. Here, it can only be assumed that users prefer to

transport things in their own vehicle or, in particular,

rate the services less highly, as they transfer their cur-

rent image of taxi and carsharing to the automated

modes. There were no significant differences between

the driving time, ease of use and safety criteria. From

an objective point of view, the criterion ease of use

requires an explanation since driving a car today is

ICE-B 2018 - International Conference on e-Business

142

currently one of the most complex and dangerous cul-

tural skills. Autonomous driving frees the user from

this complex task so that, for example, children, the

elderly and the disabled can use an autonomous car

on their own. However, as almost 95% of the re-

spondents have a driving license, this complexity no

longer seems to be decisive once vehicle control has

become routine. Rather, users fear that they will have

to learn new usage techniques. Although studies of

fully-automated vehicles predict a higher safety than

for the classic car (Howard and Dai, 2014; Eimler and

Geisler, 2015), users are skeptical, have little confi-

dence and often consider themselves to be the better

driver than a machine (Eimler and Geisler, 2015).

These two contradictory arguments lead to a neutral

evaluation in total - this is also supported by the con-

sistently high dispersion in the respondents' response

behavior (standard deviation 1.14 to 1.28).

Overall, it can be seen that the autonomous modes

of transport have (subjectively perceived) relative

disadvantages in almost all characteristics compared

to classic passenger cars. Only the driving comfort

and the use of time during the journey are considered

to be much more positive for autonomic vehicles than

for classic cars.

4.2 Relative Partworth Values

Compared to Public Transport

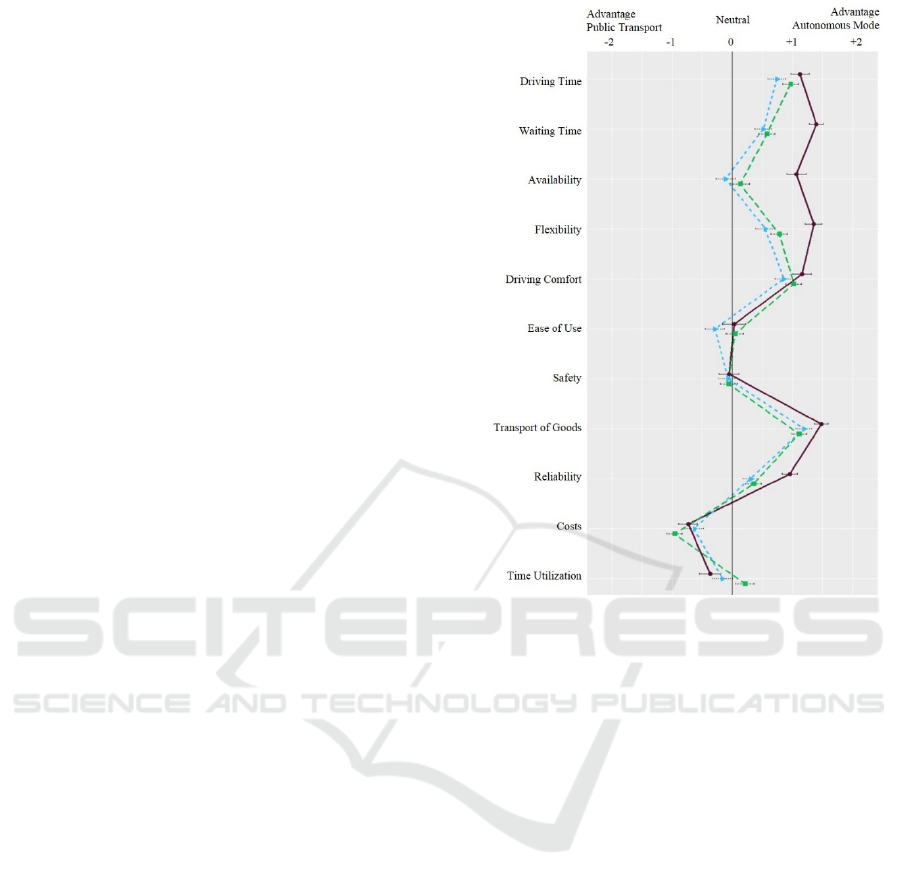

When comparing the profile lines (Figures 1 and 2) it

is noticeable that the relative added value of the fully

automated modes compared to traditional passenger

cars is much lower than when the comparison is be-

tween fully automatic modes and public transport.

While many aspects of the new autonomous travel

modes are seen as worse or equivalent to conven-

tional cars, the opposite is true for public transport.

This confirms the results of our preliminary study,

which showed that users would prefer autonomous

modes of transport over public transport but not over

today's private car (Pakusch et al. 2018).

Compared to public transport, all three autono-

mous modes offer a significant relative advantage (of

+0.68 for the autonomous car, +0.26 for autonomous

carsharing, and +0.38 for autonomous taxis. As Fig-

ure 2 shows not only does the autonomous private car

perform better in almost every aspect but the autono-

mous mobility services taxi and carsharing also do

except for costs, ease of use (only for carsharing), and

time use (for autonomous cars). In all other areas, re-

spondents consistently attest the benefits of autono-

mous modes. In this context, due to its access at any

time, the private autonomous passenger car again out-

performs autonomous mobility services as expected

in the criteria of waiting time, reliability, availability

and flexibility.

4.3 Intention to Use Future Travel

Modes

The answer to the question as to which mode of

transport the respondents could envisage owning or

using regularly in the future shows that private cars

will continue to occupy a central position. Almost

90% of the respondents (very) likely would continue

using private cars, followed by public transport with

about 65%. It is only after these two conventional

modes that the autonomous car (37.5%) follows be-

fore the classic taxi (27.4%), the autonomous taxi

(22%), the autonomous carsharing (16.7%) and the

classic carsharing (14.3%). Carsharing is also re-

jected most strongly – respondents cannot imagine

using either the conventional (65.5%) or the autono-

mous (63.1%) variant in the future.

Although the automation of the car can objec-

tively be expected to bring much added value com-

pared to the conventional car – even more so than to

public transport (Howard and Dai, 2014; Pakusch et

Figure 2: Comparative assessment of autonomous travel

modes and public transport.

(n=172, confidence interval = 95%).

The Users’ Perspective on Autonomous Driving - A Comparative Analysis of Partworth Utilities

143

Figure 3: Intention to use/own a travel mode regularly in the future.

al., 2016; 2018) – the participants preferred the tradi-

tional travel modes, i.e. passenger car and public

transport.

Against the background of the partworth utilities

of the conventional car in comparison to the autono-

mous modes (cf 4.1), it is only reasonable that the pri-

vate car is assigned the highest intention to use. How-

ever, the fact that the intention to use public transport

in the future is higher than the intention to use auton-

omous modes of transport cannot be deduced from

the partworth analysis in Section 4.2. After analyzing

the partworth values, it would have been expected

that the many relative advantages of the autonomous

modes would have led to them being given preference

over public transport. A high relative advantage – as

in the case of those autonomous modes compared to

public transportation – of an innovation or alternative

product increases the probability of a takeover (Rog-

ers, 2003). However, Figure 3 shows that this is not

the case. One explanation is that, for public transport

users, costs are a central aspect. Furthermore, this

contradiction points to the fact that not all relevant

factors have been included in the survey, such as the

factor of environmental friendliness or other non-

product-related properties such as user-related (cus-

tom and mobility socialization (Steg, 2005)) and ex-

ternal influencing factors (Rogers, 2003). The im-

portance of experience and routines in this context

particularly points out that the perceived advantage

will only slowly assert itself in practice - but in prin-

ciple there will be latent, serious competition to pub-

lic transport with the autonomous mobility services.

In the taxi sector, too, respondents placed their

trust in the already familiar conventional version; in

these fully automatic travel modes, skepticism about

innovations and safety prevails over the supposed

added value of automation by making use of familiar

features. Only when it comes to carsharing could

respondents imagine using the autonomous variant

rather than the conventional variant. This finding is in

line with a previous study (Pakusch et al., 2018). In

this mode of transport, the advantages associated with

automation (particularly to be picked up and driven

instead of having to search for the vehicle) outweigh

the disadvantages (uncertainty, complexity of new

technology, appropriation). The change in carsharing

through automation was thus perceived by the inter-

viewees as greater and more positive than in the case

of cars. The evaluation also shows that the traffic

modes taxi and carsharing are converging due to the

self-driving technology, as predicted by Fagnant et

al., (2015) and Krueger et al., (2016) for example.

4.4 Interrelation between Partworth

Utilities and Intention to Use

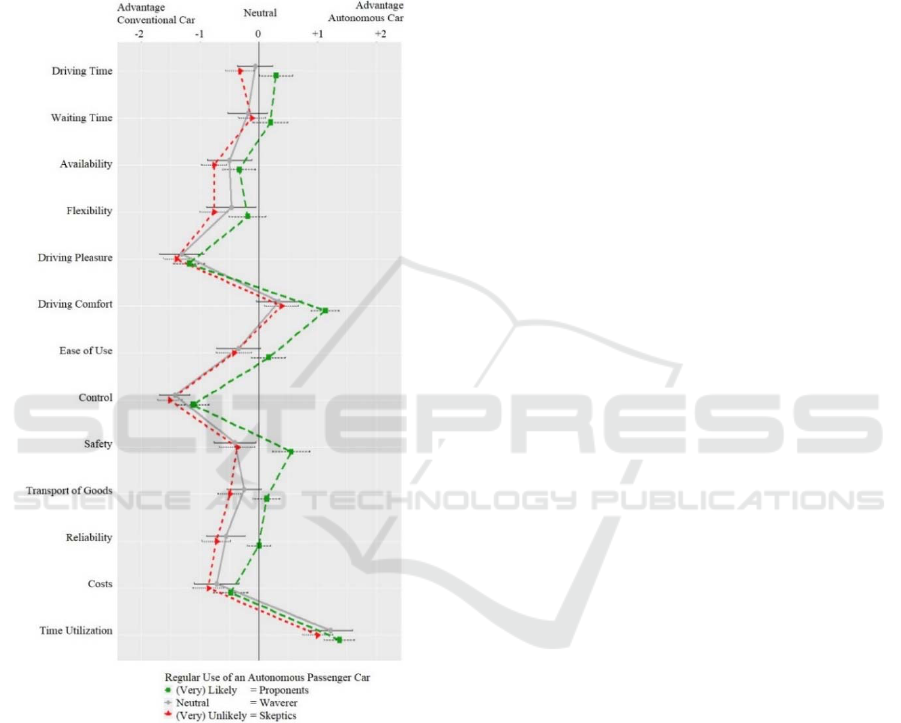

The proponents of autonomous driving rated the au-

tonomous car in all characteristics as being more ad-

vantageous compared to the traditional car than the

skeptics did. We call those users proponents who

could imagine using an autonomous car regularly in

the future (Figure 3: regular use is (very) likely) and

those skeptics who cannot imagine using an autono-

mous car regularly in the future (regular use is (very)

unlikely). It is not clear in which direction the inter-

dependence works. The proponents could have a gen-

erally positive attitude towards autonomous vehicles

and assess the partworth benefits accordingly posi-

tively. Alternatively (according to the order in which

they appear in the survey) they could see relative ad-

vantages in the individual characteristics, which con-

sequently lead to their intention to use the future

travel modes. In particular, the partworth utilities of

waiting time, availability and flexibility are rated

higher. There was also a significant difference in driv-

ing comfort. This evaluation clearly shows that the

ICE-B 2018 - International Conference on e-Business

144

proponents are much more open to the new modes

and anticipate the advantages of the self-driving tech-

nology. There are not only significant differences in

the characteristics of driving time, ease of use, safety,

and the transport of goods; while here skeptics see the

relative advantage of conventional cars, proponents

consider the autonomous car to be generally advanta-

geous.

Figure 4: Partworth assessment of proponents and skeptics

in comparing conventional and autonomous car.

(n=172, confidence interval = 95%).

4.5 Convergence of Taxi and

Carsharing

Although the evaluation of the individual characteris-

tics of the autonomous taxi and the autonomous car-

sharing indicates a convergence of the two modes, in-

dividual partworth utilitiy differences show that users

still see differences between the two modes. Overall,

there was a slight preference for the autonomous taxi.

There are two reasons for this. First, users tend to

prefer a well-known alternative. The carsharing busi-

ness model is generally less well known than the taxi

business model. Second, users prefer non-binding of-

fers. In this respect, the two concepts differ in that one

makes a regular and longer-term commitment (mem-

bership) for the use of carsharing while with a taxi

one pays only for the actual use. This insight should

be taken into account by practitioners when designing

autonomous mobility services.

5 LIMITATIONS

A limit to this study is that the sample is not repre-

sentative nor can any claim be made to completeness

with regard to the selected product characteristics.

Other factors such as habits, symbolism, etc. could

also influence travel mode choice for autonomous ve-

hicles and services. In addition, the subjective rele-

vance (weighting) of the individual criteria was not

included in the evaluation of relative partial and total

benefits. However, the study helps to improve the un-

derstanding of user acceptance of autonomous driv-

ing by taking into account alternative travel modes.

6 CONCLUSIONS

User studies show that the à priori acceptance of au-

tonomous driving is relatively high (Payre et al.,

2014; Rödel et al., 2014; Schoettle and Sivak, 2014;

Becker and Axhausen, 2017). However, they usually

view autonomous driving in isolation so that conclu-

sions about future changes in mobility behavior are

difficult to draw. Initial studies have therefore ana-

lyzed user preferences for the new traffic modes in

comparison with existing traffic modes and have

shown that users continue to prefer private cars, re-

gardless of whether they are traditional or fully auto-

mated. However, in a direct comparison, carsharing

benefits much more from full automation than do in-

dividual passenger cars (Pakusch et al., 2018). The

present survey showed that users see advantages in

the automation of cars, taxis and carsharing in terms

of driving comfort and time utilization, but in many

other areas they fear no added value or even signifi-

cant disadvantages compared to the conventional car.

The opposite is true for public transport: all three au-

tonomous travel modes offer significant relative

added value compared with public transport. From

the user's point of view, public transport only retains

a competitive advantage in terms of costs and ease of

use. The intention to use a travel mode in the future is

The Users’ Perspective on Autonomous Driving - A Comparative Analysis of Partworth Utilities

145

still the highest for traditional passenger cars, ahead

of public transport, autonomous private cars, conven-

tional taxis, autonomous taxis, autonomous carshar-

ing and conventional carsharing. A closer look at the

user ratings shows that the proponents of autonomous

vehicles anticipate a higher partworth utility in all

properties than the sceptics do.

Overall, the results suggest that autonomous driv-

ing will gain acceptance in the short to medium term,

especially for private transport, while usage-based

(sharing) models can only become established in the

long term. It is only through experience and new rou-

tines that the relative advantage of autonomous mo-

bility services will prevail, which could then become

a serious competition for public transport.

REFERENCES

Becker, F., Axhausen, K.W. 2017. Literature review on sur-

veys investigating the acceptance of automated vehi-

cles. Transportation 44:1293-1306.

Bunghez, C.L. 2015. The Future of Transportation-Auton-

omous Vehicles. International Journal of Economic

Practices and Theories 5:447-454.

Cyganski, R., Fraedrich, E., Lenz, B. 2015. Travel-time val-

uation for automated driving: A use-case-driven study.

Proc. of the 94th Annual Meeting of the TRB.

Ding, L., Zhang, N. 2016. A travel mode choice model us-

ing individual grouping based on cluster analysis.

Procedia engineering 137:786-795.

Eimler, S.C., Geisler, S. 2015. Zur Akzeptanz Autonomen

Fahrens. Mensch & Computer, 533-540.

Fagnant, D.J., Kockelman, K.M., Bansal, P. 2015. Opera-

tions of Shared Autonomous Vehicle Fleet for the Aus-

tin, Texas Market. Journal of the Transportation Re-

search Board 98-106.

Gorr H (1997) Die Logik der individuellen

Verkehrsmittelwahl. Focus-Verlag.

Howard, D., Dai, D. 2014. Public perceptions of self-driv-

ing cars. Transp. Research Brd. 93rd Annual Meeting.

Knapp FD (2015) Determinanten der Verkehrsmittelwahl.

Duncker & Humblot.

Krueger, R., Rashidi, T.H., Rose, J.M. 2016. Preferences

for shared autonomous vehicles. Transportation re-

search part C, 69:343-355.

Kyriakidis, M., Happee, R., de Winter, J.C. 2015. Public

opinion on automated driving. Transportation research

part F, 32:127-140.

Lancaster, K.J. 1966. A new approach to consumer theory.

Journal of political economy 74:132-157.

McFadden, D. 2000. Disaggregate behavioral travel de-

mand’s RUM side. Travel behaviour research 17–63.

Nordhoff, S. 2014. Mobility 4.0: Are Consumers Ready to

Adopt Google’s Self-driving Car? University of

Twente.

Pakusch, C., Bossauer, P. 2017. User Acceptance of Fully

Autonomous Public Transport. Proc. of the 14th

International Joint Conference on e-Business and Tel-

ecommunications (ICETE 2017). pp 52-60.

Pakusch, C., Bossauer, P., Shakoor, M., Stevens, G. 2016.

Using, Sharing, and Owning Smart Cars. Proc. of the

13th International Joint Conference on e-Business and

Telecommunications (ICETE 2016). pp 19-30.

Pakusch, C., Stevens, G., Bossauer, P. 2018. Shared Auton-

omous Vehicles: Potentials for a Sustainable Mobility

and Risks of Unintended Effects. Proc. of ICT4S. EPiC

Series in Computing, 258-269.

Payre, W., Cestac, J., Delhomme, P. 2014. Intention to use

a fully automated car. Transportation research part F,

27:252-263.

Piccinini, E., Flores, C., Vieira, D., Kolbe, L.M. 2016. The

Future of Personal Urban Mobility–Towards Digital

Transformation. Wirtschaftsinformatik MKWI, 55-66.

Ponnuswamy, S., Anantharajan, T. 1993. Influence of

travel attributes on modal choice in an Indian city. Jour-

nal of advanced transportation 27:293-307.

Rödel, C., Stadler, S., Meschtscherjakov, A., Tscheligi, M.

2014. Towards autonomous cars: the effect of auton-

omy levels on acceptance and user experience. Proc. of

the 6th Int.l Conference on Automotive User Interfaces

and Interactive Vehicular Applications. ACM, 1-8.

Rogers, E.M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition.

Simon and Schuster.

SAE International 2016. Automated driving levels of driv-

ing automation. Standard J3016.

Schoettle, B., Sivak, M. 2014. A survey of public opinion

about connected vehicles in the US, the UK, and Aus-

tralia. Connected Vehicles and Expo (ICCVE), 2014 In-

ternational Conference on. IEEE, 687-692.

Steg, L. 2003. Can public transport compete with the pri-

vate car? IATSS Research 27:27-35.

Steg, L. 2005. Car use: lust and must. Instrumental, sym-

bolic and affective motives for car use. Transportation

Research Part A, 39:147-162.

Verplanken, B., Aarts, H., Knippenberg, A., Knippenberg,

C. 1994. Attitude versus general habit: Antecedents of

travel mode choice. Journal of Applied Social Psychol-

ogy 24:285-300.

Vredin Johansson, M., Heldt, T., Johansson, P. 2004. Latent

variables in a travel mode choice model. Statens väg-

och transportforskningsinstitut.

Zmud, J., Sener, I.N., Wagner, J. 2016. Consumer ac-

ceptance and travel behavior: impacts of automated ve-

hicles. Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

ICE-B 2018 - International Conference on e-Business

146