Innovation Governance in Chinese Family Business: A Case Study

Thomas Menkhoff and Ong Geok Chwee

Lee Kong Chian School of Business, Singapore Management University, Singapore

Keywords: Innovation Governance, Chinese Family Firms, Qian Hu, Singapore.

Abstract: Corporate innovation governance can be defined as a systematic approach to align goals, allocate resources

and assign decision-making authority for innovation, across the company and with external parties. While

the dos and don’ts of innovation governance approaches in non-Asian firms are fairly well researched, little

is known about the Chinese way of governing innovation in Asian family firms. This paper provides

insights into the innovation management capabilities of Qian Hu, an integrated ornamental fish service

provider incorporated in Singapore in 1998. Based on half-structured interviews with its Executive

Chairman and MD Mr. Kenny Yap, we exemplify the key components of Singapore’s Innovation

Excellence Award (I-Award) and how Qian Hu made them work. The paper attempts to shed light on some

of the unique innovation management approaches in Chinese family-owned enterprises, e.g. with regard to

‘family involvement in boards’ which divert to some extent from formal business excellence standards. The

paper is part of an on-going research project aimed at examining the specifics of innovation governance in

Asian enterprises.

1 WHAT IS INNOVATION

GOVERNANCE AND WHY

DOES IT MATTER

One approach to encourage more innovation in

business and beyond is to effectively govern it. In

contrast to the word innovation which refers to the

implementation of a new or significantly improved

product, service or process that creates real value,

the term governance is a bit more complex due to its

connotations of authority, control and influence. The

word itself derives from the Greek word kubernáo

with the connotation of steering a ship

(metaphorically, it refers to the challenges of

steering Men).

Broadly speaking, governance is about the nature

of authority relationships in a country or an

organisation as well as the degree of formality of

associated rules, norms, and actionable procedures -

which can vary widely (Deschamps, 2013; 2014;

2015). Corporate innovation governance can be

defined as a systematic approach to ‘align goals,

allocate resources and assign decision-making

authority for innovation, across the company and

with external parties’. Innovation governance is a

“top management responsibility” that cannot be

delegated to any single function or to lower levels of

an organisation (Deschamps, 2008).

Corporate innovation contexts are characterised

by uncertainty (How will our customers react?);

complexity (How best to manage diverse groups of

internal and external knowledge experts from

different disciplines?); low degree of predictability

(Who might disrupt us and what changes will occur

within our organisation when we develop a new

innovation strategy); and creativity (How to nurture

a climate where creativity can flourish?). Therefore,

business leaders need governance frameworks, tools

and techniques to effectively strategise innovation

efforts with a clear focus and a balanced portfolio of

innovation initiatives to make innovation work

(Adams et al., 2010).

While many would agree that winning firms are

characterised by strong innovation governance

approaches, empirical research about this topic in

Asia is rather poor. Anecdotal evidence suggests that

there are many organisations here where formal

innovation governance systems are completely

lacking. But there are also a couple of real

champions where innovation is effectively governed

via solid innovation management frameworks, top

leadership support and capable managers aimed at

creating sustainable business and societal value.

Examples include Defence Science Technology

Agency (DSTA), Sheng Siong Group and

158

Menkhoff, T. and Chwee, O.

Innovation Governance in Chinese Family Business: A Case Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0006851501580165

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2018) - Volume 1: DCNET, ICE-B, OPTICS, SIGMAP and WINSYS, pages 158-165

ISBN: 978-989-758-319-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Biosensors Interventional Technologies Pte Ltd - all

of which recently won the SPRING Innovation

Excellence Awards. Their summary reports are

available on the website of Enterprise Singapore and

provide valuable insights into key components of

innovation governance systems such as a compelling

strategic innovation vision and mission (to

determine the goals of innovation efforts), a system

of supportive values, ‘the right’ sources of

innovation, innovation process-related details and so

forth.

A good innovation governance system not only

clearly states the vision and intended goals of

innovation efforts, it also helps to clearly define

roles and responsibilities related to the innovation

process, including decision power lines (e.g. with

regard to innovation budgets) and the nature of

relationships with both internal and external

collaborators, e.g. in the context of open innovation.

It sheds light on the desired innovation culture and

specifies how the organisation intends to create and

sustain a climate in where new ideas are encouraged

and rewarded, and where failure is indeed an option

and not a shameful defeat.

Innovation governance ensures that the right

innovation metrics (e.g. ratio of incremental to

game-changing innovation in the portfolio,

measured in the number of initiatives and/or

expenditures) are used (Adams et al., 2006), and it

establishes proper management routines regarding

innovation project management, information sharing

and timely decisions with reference to the stages of

the product innovation process, such as ‘Go to

Development’, ‘Go to Testing’ and ‘Go to Launch’

(Cormican and O'Sullivan, 2004). Without a well-

balanced portfolio of incremental and radical

innovation initiatives, organisations may become too

product centric and/or too revenue impatient.

2 ENTERPRISE SINGAPORE’S

BUSINESS EXCELLENCE

FRAMEWORK

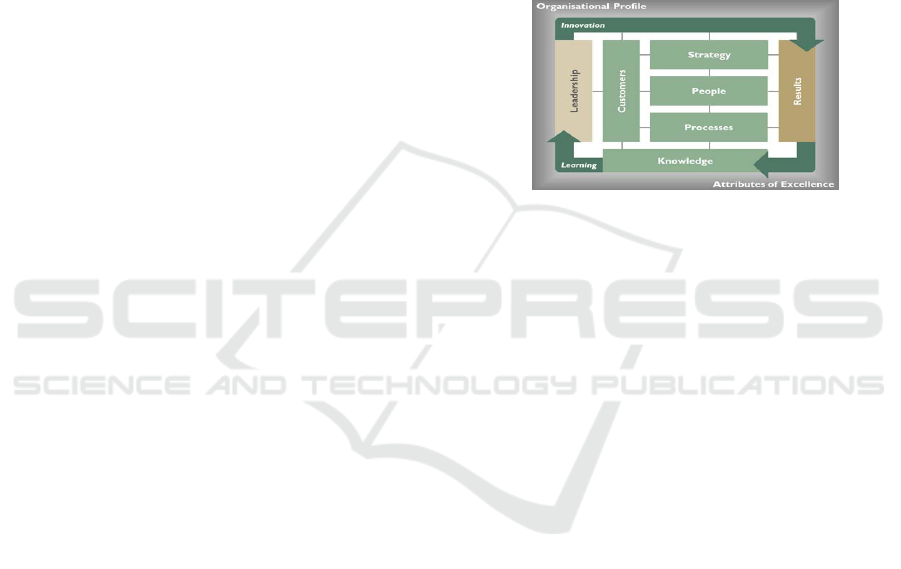

A useful tool to develop a governance system for

innovation is Enterprise Singapore’s business

excellence framework. Enterprise Singapore is a

government agency championing enterprise

development (https://www.enterprisesg.gov.sg)

under the Ministry of Trade and Industry. Its

Business Excellence Framework helps companies

build their business capabilities, improve their

organisational strengths and identify areas for

improvement. The Business Excellence (BE)

initiative was launched in Singapore in 1994 to help

organisations assess which stage they are at on the

excellence journey and what they need to do to

achieve a higher level of performance. This is done

by an assessment of organisational performance

against the requirements of the BE framework which

provides a holistic standard that covers all critical

drivers and results for business excellence. It

illustrates the cause and effect relationships between

the drivers of performance, what the organisation

does, and the results it achieves. It covers the

following areas:

Figure 1: Areas Covered by the Business Excellence

Framework.

The organisational profile sets the context for the

way the organisation operates and serves as an

overarching guide for how the framework is applied.

So-called “attributes of excellence” describe key

characteristics of high performing organisations and

are embedded throughout all critical drivers of the

framework. These are: 1. Leading with Vision and

Integrity, 2. Creating Value for Customers, 3.

Driving Innovation and Productivity, 4. Developing

Organisational Capability, 5. Valuing People and

Partners, 6. Managing with Agility, 7. Sustaining

Outstanding Results, 8. Adopting an Integrated

Perspective, and 9. Anticipating the Future.

Together, the organisational profile and the

attributes of excellence form the context and

foundation that encapsulate the entire framework as

shown in the diagram above. To achieve excellence,

an organisation needs strong leadership to drive the

mind-set of excellence and to set a clear strategic

direction. Customer-centricity is positioned after

leadership to demonstrate the focus on anticipating

customer needs and creating value for them.

Strategy is developed based on understanding

internal and external stakeholder requirements to

guide people and process capabilities required to

drive desired results. To sustain excellent

performance, organisations need to continually

learn, improve and innovate. Continuous learning

and innovation is demonstrated through acquiring

Innovation Governance in Chinese Family Business: A Case Study

159

knowledge from the lessons learned and the

measurement of results, and using them in a closed

feedback loop to support decision-making and drive

improvements.

The so-called Singapore Innovation Class is one

of four standards and certification programmes

based on the BE framework interested companies

can choose from (based on the same seven

dimensions of excellence, namely, Leadership,

Planning, Information, People, Processes, Customers

and Results). Singapore Innovation Class (I-Class)

offers certification for business excellence in

innovation aimed at helping organisations to develop

their innovation management capabilities. There

were 107 I-Class certified organisations as of

October 2016.

Launched in 2001, the Innovation Excellence

Award (I-Award) recognises organisations for

outstanding innovation management capabilities

resulting in breakthrough or impactful innovations

observed in areas such as business models,

processes, and products and services (Mcgrath,

2010).

3 MANAGERIAL AND

ORGANIZATION FEATURES

OF CHINESE FAMILY FIRMS

Asian enterprises are dominated by Chinese family

businesses, i.e. both small and large business

organizations owned and managed by ethnic

Chinese business leaders (Menkhoff et al., 2008;

Menkhoff and Gerke, 2004). Despite prevailing

notions about their growth restrictions due to

cultural characteristics such as familism (nepotism)

or lack of professionalism, many of them have

developed into globalised MNCs as exemplified by

firms such as the Oversea-Chinese Banking

Corporation (OCBC), the Hong Leong Group or Eu

Yan Sang International. Contrasting ‘traditional

Chinese’ vs. ‘modern Western’ organisations and

their ‘typical’ attributes does not always reflect

empirical reality in fast changing Asia because of

growth dynamics and intergenerational transitions as

stressed by Fock (2009) or Menkhoff et al., (2014).

A typical example of a local Chinese family firm

is integrated ornamental fish service provider Qian

Hu which was incorporated in 1998 (Menkhoff,

2008). Since 2000, it is listed on the Singapore

Exchange. The firm’s business activities include the

breeding of Dragon Fish as well as farming,

importing, exporting and distributing of over 1,000

species and varieties of ornamental fish. The

company under the leadership of Kenny Yap also

produces and distributes several aquarium and pet

accessories (http://www.qianhu.com/about-qian-

hu/corporate-profile). In 2013, Qian Hu won the

Innovation Excellence Award (I-Award).

3.1 Comment on Research Method

In the following, we will present selected insights

from an ongoing study on the innovation governance

specifics of Asian family firms based on the

grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) and case

study approach (Yin, 2014; Bernard, 2000) to

uncover what makes innovation tick in Asian

enterprise.

4 INNOVATION GOVERNANCE

AT QIAN HU

4.1 Visionary Innovation Leadership

According to Kenny Yap, innovation is extremely

important in the changing business environment,

especially in Singapore with its continuous emphasis

on improving productivity:

“How do you increase your productivity? It's

only through innovation. There's no other way. You

say ‘you save a little bit here and there’. That’s not

significant. You've got to create some significant

and impactful kind of productivity increase. You

have to go for innovation because innovation is

about finding new things to do, which you can do to

increase the value added…It's extremely important

for any company, especially for SMBs, because the

impact of the disruptions of technology is going to

make them die faster than the bigger company”.

The CEO “must be the key driver” of innovation

efforts because the management staff may not

always have the complete picture about finance and

other resources:

“If the CEO does not have the heart and the

belief in making innovation work, I don't think that

the organization can do that. Who are those groups

of people that are heavily involved? Usually all the

top management members … and then you have to

empower all the other people to try, you know, to

come up with new things. This is why I say

innovation is broad-based. Of course, you have to

have a certain kind of hierarchy and chain of

command. But basically, I want to involve

everybody. Every project small or big must make a

ICE-B 2018 - International Conference on e-Business

160

difference”.

4.2 Strategy as Driver of Customer

Satisfaction, Innovation and

Productivity

Since its ISO 9002 certification in 1996, Qian Hu

has put emphasis on value creation through quality

products and processes. Through Qian Hu’s new e-

shop, for example, customers have easy access to the

firm’s quality products at competitive prices. Qian

Hu started to innovate internal processes in 1997 by

semi-automating their packing processes while most

of the other fish farms still relied on manual

processes: “But we semi-automated. We also

integrated the weighting machine, computers, and all

these to generate packing orders or the invoice. We

started the whole thing back in 1997. There was a

government agency called Productivity Board which

helped us”.

In 2009, a strategically integrated R&D division

was formed to spearhead the firm’s research and

development efforts. For Kenny technology is a key

innovation driver:

“No matter what kind of new things you do, you

have to involve technology. So technology is

something that I wanted to put in. Before I retire, I

want people to call Qian Hu a technology company.

Not a fish company because, regardless of what we

do, we use technology to enable what we are doing”.

Over the years, Qian Hu has implemented

numerous innovative projects, automated processes

and increased efficiency, for example, by developing

a new filtration system called HydroPure as part of

its R&D driven technology innovation efforts:

“Conventionally we used filter material but now

we use current electrolytes to break down the things

that we don't want like ammonia. We retain all the

minerals. So that’s new. Of course, we have to spend

a lot of money on it. During the past few years, Qian

Hu was not doing too well but is profitable - not as

profitable as before. I always tell my shareholders,

‘if I stop doing innovative projects or invest in R &

D, I can show you the numbers; but Qian Hu will die

after I leave the company’. So this is why I always

say, ‘a CEO’s job is to think beyond the current

generation kind of business’”.

R&D is critical for further differentiating Qian

Hu from its competitors. Recently, the firm has

moved into edible fish:

“Innovation helps us to diversify into other

things. This is why it is extremely important for

Qian Hu. We have been doing a lot of innovative

things, and we invested a lot in R&D. We are able to

diversify quite smoothly. The learning process of

going into edible fish is slightly shorter than any of

the things that we attempted before”.

To ensure business continuity and successful

strategy execution, a long-term business perspective

is important. A short-term business perspective

based on quarterly reporting can hurt the business

quite badly:

“I'm lucky because nobody can fire me because

my family owns the business so I can think long

term. Just imagine an employed CEO, the bonus tied

to annual results and he not being ethical, the

company will collapse. So I say, ‘sometimes I do not

know what shareholders want’… When they buy a

share today, they expect that it appreciates by 10%

the next day. They never have the heart, and so I

say, ‘I will care for my employee more than you.

Because I'm the bigger shareholder. I know how to

take care of the shareholders already. You are the

short term ones. I'm the long term one. And my

employees actually create value for you’. This is the

truth but nobody wants to say that. But I dare to tell

my shareholders that. I say, ‘whether you like it or

not, it's a free market, free will, you can always sell

Qian Hu share’”.

With regard to the importance of formalizing

innovation strategy per se, Kenny has a dualistic

view. On the one hand, Qian Hu has implemented a

strategic, formalised approach towards innovation

based on a 5-year plan which has helped the firm to

clinch the SPRING innovation award:

“We have all the systems of doing innovative

things. The whole process is being audited and we

got the Singapore SQA award. We are also a people

excellence award winner. We also got the

innovations award. We have the whole systems of

getting all the people involved in place”.

But on the other hand, Qian Hu’s boss believes

that it is important to maintain a more organic, less

structured approach towards innovation management

driven by an innovation-friendly environment:

“Structuring innovation is so unreal. I remember

in the army we had these work improvement teams,

a structured work improvement approach. The HQ

forced us to come up with an innovation and then, if

you did not, you had issues. You know innovative

ideas can just suddenly appear. So we give our staff

a good environment - whenever they have a good

idea, when they propose it to us, and we think its

good, we will implement it, and we'll recognize

them by giving them a plaque or a monetary award.

So we have this system of asking all the people, the

ground people, to be innovative. And, of course,

during top management meetings we always talk

Innovation Governance in Chinese Family Business: A Case Study

161

about the new things that we do that can create an

impactful outcome”.

With regard to budget-driven, strategic R&D

management approaches, a flexible approach works

better according to Qian Hu’s leader: “Budgeting R

& D does not really make sense because you never

know when a good idea comes out. Between 2011

and 2017, our expenditures for R&D were higher

than our annual net profit. The R & D budget

fluctuates. Besides my revenues, it's based on what

kind of good ideas come up every year. You don't

wait or say, ‘oh, I don't have a budget - let's wait.

No, no, no’. This year I have three projects on hand.

I know it's going to eat into a lot of my expenses and

all that. But I say, ‘do it now’. I mean, like, why do I

have to schedule it. Just do it. Unless you say you

can't because you do not have the right people.”

4.3 Differentiation and Impact:

Criteria for Project-related R&D

Decisions

Asked how he determines and decides whether a

project is worth investing into, Kenny stressed that

important criteria include its impact and whether it

helps Qian Hu to further differentiate itself from

other companies. At the moment the firm is doing a

project with NUS (National University of

Singapore) to produce high value fish albino. It

involves two Ph.D. researchers: “We had to sponsor

them for four years. Their Ph.D. projects focus on

this technology. Later, I might employ them if I

think they are good and if they can strengthen my

R&D”.

Sometimes he uses his gut feelings when it

comes to decisions about innovative R&D projects:

“You can not always put numbers on the paper

and do all the changes because those really stifle

your decision making process. You have to look at a

person. Can I trust you? Yes, I think I can. Because

the way you talk. Okay, anyway, I know this

professor X for several years already. So I know his

character. All these kinds of things will come

together and help to form my opinion to say ‘yes

we'll do this project’”.

Minor decisions about potential new projects are

delegated to his Deputy Directors and the MDs of

the firm’s subsidiaries:

“Only when it comes to major ones involving

millions of dollars or half a million or so that are

going to drag down profit, they have to inform me.

And then I will approve or not. Minor ones, you

know, as long as they are below hundred thousand

Singapore dollars they can go and do that so they

don't go bothering me”.

4.4 Valuing and Rewarding People

Kenny puts great emphasis on building a robust

culture of innovation:

“You must have a culture of doing these kinds of

things. It's all about culture anyway. The identity of

any company is determined by the culture and the

behaviour of the upper management”. One way of

endorsing this is to put it into the mission statement

so that employees know that the company tries to be

different.

In terms of staff participation and innovation

efforts, management tries to involve everyone by

making people “a little bit more creative” and by

creating an environment to try things without getting

penalized when mistakes are made:

“Making a mistake twice is a stupid mistake.

They must learn from the first mistake. How do

people get wisdom? You make a lot of mistakes.

You have a lot of experiences, and when you come

to a certain age you become wiser because of these

experiences. Without all the mistakes do you think

you can have the experience? I don't think so”.

As Kenny pointed out, responsible employees do

care about the survival of the company and its

sustainability:

“If the company can survive, they will bring

good things to other people. Responsibility is a

must. The other thing is attitude. The attitude

towards life and towards what is right and what is

wrong also determines how you want to run the

company. Try to bring good things to other people.

When I employ an employee, we look at attitude

first of all”.

Qian Hu has a system to reward staff for

suggesting good ideas: “Every month or any week,

staff can come up with some things that we think are

fantastic, and immediately we will reward them

during that month rather than drag it to the end of

the year... Innovation things cannot have KPIs.

Innovation is a feel. Innovation is a behavioural

thing. Creativity is about certain daily behaviors and

certain actions that define certain kinds of outcomes.

You don't go and measure this. When they do all the

things right, eventually the outcomes will show. You

don't have to specifically reward certain types of

ideas because you stifle the way you come up with

new ideas… Let them try everything. Think outside

the box”.

To generate innovative ideas through external

collaborations Qian Hu has recently invested into a

start-up:

ICE-B 2018 - International Conference on e-Business

162

“We have one project which is a start-up. A few

years ago it was struggling but I really believe they

have a good product, and they have knowledge that

we need… We might want to acquire the company. I

think the best way to assess that is to do a project

first and then see whether the management people

are comfortable with it. If we are, then we might

acquire the company. We have attempted to do that

before, e.g. acquiring medical plant-based formula.

You know, we tried to go into aquaculture but we

refused to use antibiotics. But we must have some

things to treat them when they get sick, right? We do

acquire herbal formula or other kind of things

because it would take us years to develop that on our

own”.

4.5 Innovation Governance at Board

Level

Asked about the role of the board in the area of

innovation (Zahra and Pearce, 1990; Liang et al.,

2013; Zhou and Li, 2016), Kenny stressed that this is

contingent upon the stage of business development,

the importance of technology as innovation lever

and the required expertise. Board members may

change according to the needs of the company:

“Initially we only had lawyers, accountants or

consultants. Some of my ex-consultants became my

board members. The IPO lawyer became my board

member. A few years ago I started replacing some of

the board members or added in new board members

with more emphasis on innovations or technology.

Two or three years ago I asked a retired AVA

expert, head of fisheries with a PhD in fish disease

and other things, to become a board member. I

believe that if NUS has no problem with the lecturer,

after the albino project I might invite him to become

my board member. So I develop board members

according to the needs of the company”.

Kenny doesn’t want to have “all the politics”

which are typical for larger organizations:

“A small company can be controlled by me or by

my family. I know exactly what the company needs.

We hate politics. I told my people ‘if you want to

play politics, become a politician. Don't become a

Qian Hu family member. We don't do this’. If you

have anything, put it on the table. Address it. Move

on. Life should be like that. Life should not, you

know, be about back stabbing or having grievances

or grudges against someone. Just be a happy ... I

want Qian Hu to be a happy company, and in a

happy company employees are happy… Not happy

in terms of financial results but whether I'm also

doing some things that are beneficial to other people.

One of the greatest things I told my brothers, my

friends and during some other open occasions, the

greatest satisfaction for me is not because I'm the

CEO of Qian Hu, it's because when I look at my

brothers and I look at my employees, Qian Hu has

made many millionaires over the years. If they know

how to save and if they don't spend it all”.

4.6 Family Matters

Most of Qian Hu’s shares are owned by the Yap

family (over 50% according to Kenny). Top

management comprises 30% family members while

70% are outside professionals.

Kenny puts strong emphasis on family values:

“Actually, you know, when I created Qian Hu, when

we listed the company, I was aware of the

importance of corporate culture and values. So this

is why you have to put in something to tell people

what we believe in and what we care about. So the

kind of behavior dictates our attitude. How do I

come up with all these kinds of things? It's because I

pick and choose from my Yap family values and

culture and I just put it there and I said, ‘we call it

Qian Hu family members’ so there are family

elements of all the people involving in this entity.

This is what you see right now, whatever you can

sense in terms of culture and values, its part of the

Qian Hu family values. Regardless of race, sexual

preferences, gender, you know, religion and all that,

if you concur with my values and you agree with my

culture, right, you're part of the Qian Hu family. So

we expanded the definition of the Qian Hu Family”.

Kenny is proud that the Qian Hu business has

helped its staff to provide their families with a

brighter future:

“We came from a poor family … Maybe I have

helped society to keep certain families well-off by

working. That’s one of the biggest incentives for me

to come to work, rather than anything else. I think

maybe Qian Hu has created something good in the

broader sense of it”.

5 CONCLUSION AND

IMPLICATIONS

In this paper, we provided insights into the

innovation management philosophy of Kenny Yap,

the leader of a Chinese family-based enterprise

(Qian Hu) in Singapore with reference to innovation

governance. The term corporate innovation

governance refers to a systematic approach to align

Innovation Governance in Chinese Family Business: A Case Study

163

goals, allocate resources and assign decision-making

authority for innovation, across the company and

with external parties (March, 1991; Waldman et al.,

1991; Deschamps, 2008). Key capabilities include

Kenny Yap’s visionary and values-based innovation

leadership cum strategic innovation approach as

exemplified by the emphasis on family continuity,

value creation through R&D and product

innovations beyond existing ones such as the Lumi-

Q fish tank. Qian Hu’s innovation governance

approach can be described as both explorative and

exploitative. ‘Yap family values’ serve as guidance

system for managing both people and partners while

business processes are optimised through IT and

strategic L&D approaches with a view towards

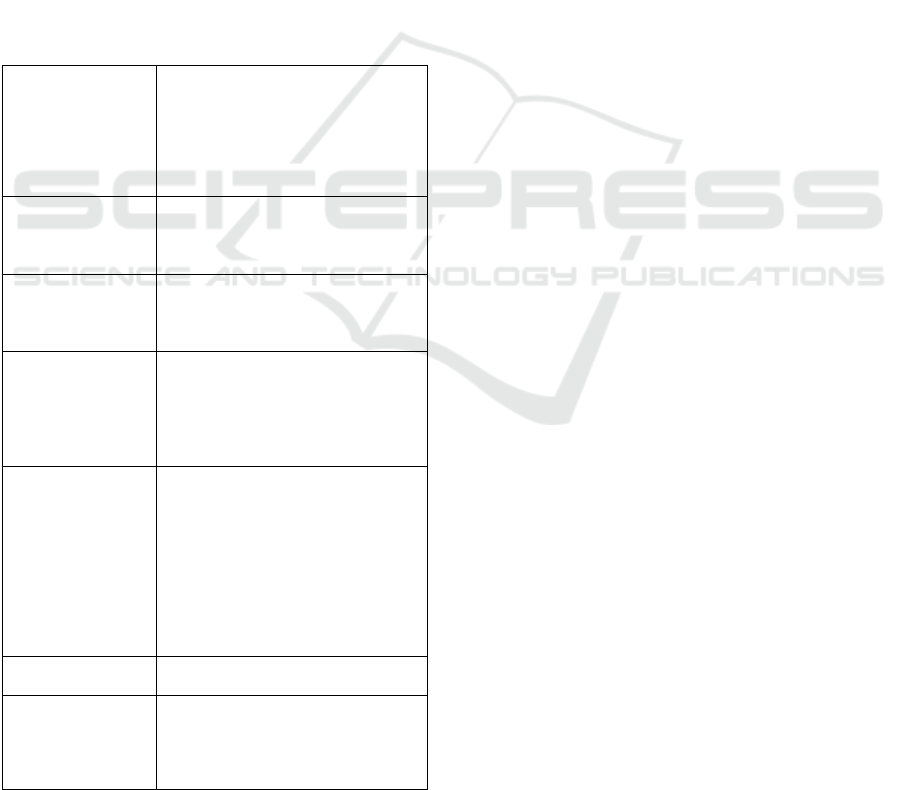

achieving greater business results. Table 1

summarizes key components of Qian Hu’s

innovation governance capabilities.

Table 1: Features of Qian Hu’s Innovation Management

Capabilities.

Leading with Vision

and Integrity

Values-based leadership with a focus

on quality, innovation, technology

and productivity improvements

combined with bottom-up staff

participation (e.g. based on the

‘creating value from mistakes’

approach)

Creating Value for

Customers

Value creation through quality

products and processes

Improved customer satisfaction index

Fas

t

(er) on-time delivery

Strategy as Driver of

Innovation and

Productivity

5-year product and process innovation

plan

Technology and business model

innovation

Valuing People and

Partners

Staff dialogues, open channels,

project teams, career development

Increasing support for innovation

learning

Improved staff innovation index and

length of service

Managing Processes

with Agility

Harvesting creative ideas and

implementing them to create value for

the organization

Use of patented HydroPure

technology to provide optimum

healthy water conditions for the fish

Leveraging IT to increase process

efficiency, e.g. zero error in

shipments

e-shop (e-commerce)

Knowledge and

Learning

KM system and strategic human

capital developmen

t

Sustaining

Outstanding Results

Improved sales turnover for

innovative, patented accessories,

trademarks, R&D investments vs.

sales, operational improvements (e.g.

lobster quarantine), patents

Not surprising perhaps if one scans the literature

on Chinese family firms and innovation (e.g. Roed,

2016), the study revealed that the innovation

governance at Qian Hu corporation is driven by the

Executive Chairman himself (rather than other

people appointed by him or the Board). ‘Family

involvement’ in Qian Hu’s board seems to

strengthen the relationship between R&D investment

and the firm’s innovation performance. The role of

Qian Hu’s Board in innovation governance turned

out to be skewed towards providing expertise that

the firm needs (again, that seems to be directed by

‘the boss’ as well) while Kenny himself stands out

as the company’s ‘Innovation Czar’. Decisions about

major innovation investments are mainly made by

Kenny himself while smaller ones are delegated to

those managers who are responsible for the business

units. As a result, innovation governance in this

dynamic Chinese family firm is arguably very

different compared with large, non-family owned

organisations (Hendry and Kiel, 2004) and the

premises of the Anglo-American corporate

governance model.

Besides this key hypothesis, the interview data

point to a couple of other important components

such as proactive innovation leadership with a clear

vision towards innovation and productivity

improvements, a robust organisational culture and

inclusive family values beyond the immediate

family as drivers of intra-organizational innovation

efforts as well as disdain for a codified (rigid)

innovation strategy. The entire management

approach at Qian Hu comes across as being organic

and contingent rather than inorganic-mechanistic

which arguably is well aligned with the current

VUCA environment.

Challenges ahead include the search for novel

business model components beyond ornamental fish,

accessories, plastics and e-retail (in a bearish

operating environment) as well as continuous

technology innovation in order to create and capture

new value.

REFERENCES

Adams, R., Bessant, J., & Phelps, R., (2006). Innovation

management measurement: A review. International

Journal of Management Reviews, 8(1), 21-47.

Adams, R.B., Hermalin, B.E., Weisbach, M.S., (2010).

The role of boards of directors in corporate

governance: A conceptual framework and survey.

Journal of Economic Literature 48, 58–107.

ICE-B 2018 - International Conference on e-Business

164

Bernard, R., (2000). Social research methods: Qualitative

and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage publications.

Cormican, K., & O'Sullivan, D., (2004). Auditing best

practice for effective product innovation management,

Technovation, Volume 24, Issue 10, October 2004,

819-829.

Crossan, M., & Apaydin, M., (2010). A multi-dimensional

framework of organizational innovation: A systematic

review of the literature. Journal of Management

Studies, 47(6), 1154-1191.

Deschamps, J.-P., (2008). Innovation Leaders: How

Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain

Innovation. Chichester, Wiley/Jossey-Bass.

Deschamps, J.-P, (2013): What is innovation governance?

– Definition and scope, Organization & Culture, May

3.

Deschamps, J.-P., (2014). Innovation governance: How

top management organizes and mobilizes for

innovation (co-authored with Beebe Nelson).

Wiley/Jossey-Bass - April 2014.

Deschamps, J.-P., (2015). Innovation governance: How

proactive is your board? Asian Management Insights,

2, (2), 74-77.

Dong I. Jung, Chee Chow and Anne Wu, (2003): The Role

of Transformational Leadership in Enhancing

Organizational Innovation: Hypotheses and Some

Preliminary Findings, The Leadership Quarterly 14,

525–544.

Fock, S.T., (2009). Dynamics of Family Business: The

Chinese Way. Singapore: Cengage Learning.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A., (1967). The Discovery of

Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research.

New York: Aldine Publishing Co.

He, Z.-L., Wong, P.-K., (2004). Exploration vs.

exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity

hypothesis. Organization Science 15(4) 481–494.

Hendry, K., Kiel, G.. (2004). The role of the board in firm

strategy: Integrating agency and organisational control

perspectives. Corporate Governance: An International

Review, 12(4), 500-520.

Liang, Q., Li, Xinchun, Yang, X., Lin, D., Zheng, D.

(2013). How does family involvement affect

innovation in China? Asia Pacific Journal of

Management, 30(3), 677–695.

March, J. G.. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in

organizational learning. Organization Science, 2: 71–

86.

Mcgrath, R. G., (2010). Business models: A discovery

driven approach. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 247-

261.

Menkhoff, T., Gerke, S., (2004). Chinese

Entrepreneurship and Asian Business Networks,

London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon.

Menkhoff, T., (2008). Case Study Knowledge

Management at Qian Hu Corporation Limited, Asia

Productivity Organization (APO), Knowledge

Management in Asia: Experience and Lessons. Report

of the APO Survey on the Status of Knowledge

Management in Member Countries. Tokyo: APO,

2008, pp. 177-192 (ISBN: 92-833-2382-3).

Menkhoff, T., Chay, Y.W., Evers, H.-D. and Hoon, C.Y.

eds. (2014). Catalyst for Change - Chinese Business in

Asia. World Scientific Publishing.

Ramanujam, V., Mensch, G., (1985). Improving the

strategy‐innovation link. Journal of Product

Innovation Management, 2(4), 213-223.

Roed, I., (2016). Disentangling the family firm’s

innovation process: A systematic review. Journal of

Family Business Strategy, 7, 185-201.

Schmidt, S., Brauer, M., (2006). Strategic governance:

How to assess board effectiveness in guiding strategy

execution. Corporate Governance: An International

Review, 14(1), 13-22.

Tushman, M. L., O'reilly, C. A., (1996). The ambidextrous

organizations: Managing evolutionary and

revolutionary change. California Management Review,

38(4), 8-30.

Urquhart, C., (2013). Grounded Theory for Qualitative

Research: A Practical Guide, Los Angeles, Calif.;

London: SAGE.

Waldman, D. A., Bass, B. M., (1991). Transformational

leadership at different phases of the innovation

process. The Journal of High Technology Management

Research, 2(2), 169-180.

Wong, R., (2008). A New Breed of Chinese

Entrepreneurs? Critical Reflections, in: Wong, R.

(ed.), Chinese Entrepreneurship in Global Era.

London: Routledge, pp. 3-22.

Yin., R.K., (2014). Case study research: Design and

methods (5th Edition). Sage Publications. California.

Zahra, S.A., Pearce, J.A., (1990). Determinants of board

directors' strategic involvement. European

Management Journal, 8(2), 164-173.

Zhou, T., Li, W., (2016). Board governance and

managerial risk taking: Dynamic analysis. The

Chinese Economy, 49(2), 60-80.

Innovation Governance in Chinese Family Business: A Case Study

165