Unobtrusive Psychological Profiling for Risk Analysis

Adam Szekeres and Einar Arthur Snekkenes

Department of Information Security and Communication Technology,

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Gjøvik, Norway

Keywords:

CEO, Psychological Profiling, Unobtrusive Measures.

Abstract:

The main objective of this exploratory study is to present how publicly observable variables reflecting indi-

vidual choice can be used to construct psychological profiles suitable for predicting behavior in the context

of risk analysis. For the purpose of demonstration, this study aimed at testing the hypothesis that there is a

selection bias among chief executive officers (CEOs), which is manifested in their personal value structures.

Values capture motivational forces that serve as guiding principles in people’s life when making decisions.

From a risk management perspective, it is crucial to understand key decision maker’s motivation in order to

be able to prepare against potentially undesirable behavior. Therefore the second objective of this study re-

lates to a detailed characterization of the observed value structures among a group of CEOs. To accomplish

these goals a non-obtrusive data collection method is utilized that requires no direct access to individuals - the

Watson Personality Insights service provided by IBM - which infers value profiles based on written or spoken

text by the subjects. Results show that CEO value profiles differ from the general population in several ways.

Furthermore, slight differences were identified between the profiles of CEOs associated with moral hazard and

CEOs not associated with it. These findings indicate that there is a meaningful selection bias and these results

contribute to the real-world applicability of the CIRA method of risk analysis.

1 INTRODUCTION

A great amount of evidence suggests that key decision

makers can have a major impact (positive or negative)

on the safety and security of organizations and infor-

mation systems spanning across the entire range of

the corporate hierarchy (Cohan, 2002; Van Peursem

et al., 2007; Soltani, 2014). Within the economics

and management literature the tension between man-

agement interests and governance objectives is rec-

ognized as the principal-agent problem within agency

theory. Agency theory addresses the situation where

one party (principal) delegates work to another party

(agent) who is responsible for performing that work

on behalf of the principal. According to Eisenhardt

the theory is concerned with resolving two problems

that may arise in any agency relationship (Eisenhardt,

1989). The first problem relates to the possibility that

the agent’s and the principal’s desires and goals are in

conflict, and it is difficult or expensive for the princi-

pal to verify what the agent is actually doing (i.e. it is

difficult to verify that the agent’s behavior is appropri-

ate). The second problem arises from the difference

between the parties’ attitude towards risk, where the

principal and the agent might prefer different actions

due to different risk preferences.

As more and more critical infrastructures are un-

dergoing a radical change by the introduction of the

Internet of Things (IoT), social and economic stability

is increasingly dependent upon the decisions that peo-

ple in key positions make (Fosso et al., 2014). These

aspects of risks are often neglected within informa-

tion security risk analyses, as they mostly focus on

the technical aspects, while largely ignoring the cru-

cial human influence. It is suggested by Anderson

and Moore that information security problems should

be addressed from a broad range of perspectives

(e.g. economics, psychology, etc.), since stakehold-

ers might face various misaligned incentives, while

various psychological factors can be utilized to reveal

the ways in which people pose threat to information

systems (Anderson and Moore, 2009).

The Conflicting Incentives Risk Analysis (CIRA)

developed by Rajbandhari and Snekkenes aims to

bridge the existing gap by focusing on decision mak-

ers’ motivation when addressing risks (Rajbhandari

and Snekkenes, 2012). In order to enhance the exist-

ing method and make it applicable to real-world cases

it is necessary to update the method with relevant in-

sight about human behavior. To this end this study

210

Szekeres, A. and Snekkenes, E.

Unobtrusive Psychological Profiling for Risk Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0006858802100220

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2018) - Volume 2: SECRYPT, pages 210-220

ISBN: 978-989-758-319-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

focuses on leader characteristics within an organiza-

tion and its consequences as the CEO role offers the

biggest potential to exert influence over the entire or-

ganization. However, the principles of the analysis

are applicable for the study of any type of stakehold-

ers (i.e. not limited to the CEO role). It is acknowl-

edged that people might be reluctant to be explicitly

subjected to risk analysis activities, which poses a ma-

jor obstacle in conducting the work, therefore in such

highly data-sparse environments, the analysis must

rely on publicly observable features as much as pos-

sible.

1.1 Problem Statement

The CIRA method investigates how a misalignment

between stakeholders’ motivation can result in var-

ious forms of risk. For the development of the

method, it is necessary to quantify and characterize

the strength of an individual’s motivation without di-

rect access to the subject, since subjects might be re-

luctant to reveal their real motivations or would be

tempted to mislead an analyst. Therefore for the en-

hancement of the method the objective is:

• to select a suitable framework that captures a com-

prehensive set of human motivations,

• to derive the motivational structure without direct

access to the individuals,

• to use the knowledge derived from groups of in-

dividuals in settings where data about an individ-

ual’s past choices is scarce.

1.2 Research Questions

Based on the aforementioned requirements, the pri-

mary research question that is addressed in this study

was formulated as: can publicly observable variables

reflecting individual choice be used to construct psy-

chological profiles suitable for predicting behavior in

the context of risk analysis?

The following sub-questions are addressed in or-

der to answer the main research question:

1. Is it feasible to derive motivational characteristics

of CEOs using unobtrusive measures?

2. Is there a significant difference between the basic

human value structure of CEOs in comparison to

the general population?

3. Is there any significant difference between the

value profiles of CEOs associated with moral haz-

ard and the profiles who have no association with

it?

This work contributes to the literature of risk anal-

ysis by presenting how publicly observable decisions

from individuals can be utilized for the purpose of

information security risk analysis. The presented

method builds on an existing application, while the

purpose of the analysis differs significantly from cur-

rent domains of application. In order to illustrate

the method’s practicality, the study focuses on orga-

nizational leaders due to the fact that other classes

of stakeholders might not be allowed to interact offi-

cially with the public, due to company policies, how-

ever the approach can be applicable to any class of

key stakeholders (e.g. CFO, COO, CIO, CISO).

2 RELATED WORK

This section provides an overview about the psy-

chological theories, constructs and applications that

served as the foundations of this study.

2.1 Sources of Bias

There are several research perspectives that aim to

provide an explanation about how people with certain

traits or characteristics are self-selected to leading po-

sitions, how these characteristics are desirable on one

hand and how they might have a negative impact on

the organization’s objectives, and can have greater so-

cietal impacts. This section introduces two mecha-

nisms that could contribute to a selection bias in ex-

ecutive roles (i.e. personal attraction to a specific role

and selection of candidates by relevant stakeholders).

2.1.1 Bias by Personal Motivations

Boddy defines Corporate Psychopaths “as people

working in corporations who are self-serving, oppor-

tunistic, ego-centric, ruthless and shameless but who

can be charming, manipulative and ambitious” who

are drawn to corporations as they provide sources of

power, prestige and money (Boddy, 2005). There is

a distinction between the popular image of criminal

psychopaths, and corporate psychopaths. While the

former group is pictured as insane, suffering from

mental delusions, Corporate Psychopaths are out-

wardly charming, and engaging, skillful at manipu-

lating others to their own advantage, with a lack of

concern for the consequences of their actions, and

give a high priority for the pursuit of their own goals

and ambitions. The prospects of power, prestige and

money are assumed to be the main motivators that

draw individuals with psychopathic traits to the cor-

porate world. The ability to demonstrate desirable

Unobtrusive Psychological Profiling for Risk Analysis

211

traits that the organization values for a certain position

is easily exploited by such individuals by presenting

a charming facade and appear to be an ideal leader.

The risks that such individuals pose to the corpora-

tions they work for can take various forms e.g. acting

on the basis of pure self-interest, that may hamper or-

ganizational goal achievement, when self-interest and

greater corporate interests are misaligned. The link

between an organization’s questionable practices (e.g.

exploiting sweatshop labor, environmental pollution,

etc.) in pursuit of profit is the decision-maker, who

authorizes such activities. According to the argument,

these leader characteristics contribute to a less-than

desirable social responsibility by the organization.

Babiak, Neumann and Hare empirically investi-

gated a sample of 203 corporate professionals who

were selected by their companies to take part in a

management development program for indications of

psychopathic tendencies (Babiak et al., 2010). Ac-

cording to the authors, the lack of available coop-

erative subjects is a major obstacle when the aim

is to understand how a key decision maker’s per-

sonal characteristics can negatively influence others.

However there is a “growing public and media in-

terest in learning more about the types of person

who violate their positions of influence and trust, de-

fraud customers, investors, friends, and family, suc-

cessfully elude regulators, and appear indifferent to

the financial chaos and personal suffering they cre-

ate”. Large-scale Ponzi schemes, embezzlement, in-

sider trading, mortgage fraud, and internet frauds and

schemes, are some of the activities where psychopa-

thy was invoked as one explanation for such socially

destructive behavior. The study aimed at investigat-

ing the prevalence, strategies and consequences of

psychopathy in the corporate world. According to

the results very high psychopathy scores were ob-

tained from high potential candidates who held senior

management positions. An interesting finding of the

study had to do with how the corporation viewed in-

dividuals with many psychopathic traits. High psy-

chopathy scores were associated with perceptions of

good communication skills, strategic thinking, and

creative/innovative ability and, at the same time, with

poor management style, failure to act as a team player,

and poor performance appraisals (as rated by their

immediate bosses). The findings shed some light on

the complex association between situation-congruent

self-presentation and how psychopathic traits (al-

though not classified as Antisocial Personality Disor-

der) can be adaptive in corporate environments.

An empirical study investigated the link between

the Dark Triad personality traits and the Schwartz ba-

sic human values (Kajonius et al., 2015). The Dark

Triad (Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopa-

thy) is a popular grouping of individual differences

that represent antisocial personality traits below clini-

cal threshold. The antisocial aspect of the triad comes

from the shared underlying attitudes and modes of

behavior that characterize these traits. Entitlement,

superiority, dominance, manipulativeness, lack of re-

morse, impulsivity are among the key features of the

triad. The study found in two different cultures (i.e.

Swedish and American) that Hedonism, Stimulation,

Achievement and Power values were the most impor-

tant values held by individuals high on Dark Triad

traits. The authors conclude that those character-

ized by high scores on the Dark Triad traits, hold

values that imply the exclusion of others and self-

enhancement, viewing others as means toward self-

ish gains. The connection between Self-enhancement

values and the Dark Triad traits is referred to as dark

value system that has further moral implications.

2.1.2 Selection Bias by Requirements of the Role

Person-organization fit is a specialized area of inquiry

within the broader Person-environment fit studies that

aims to investigate how certain personality character-

istics influence the fit of the individual within organi-

zational settings. Morley (Morley, 2007) discusses a

recent shift in the recruitment process where the tra-

ditional focus on knowledge, skills, abilities (KSAs),

has shifted toward seeking an optimal fit between the

candidate’s personality, beliefs and values and the or-

ganization’s espoused culture, norms and values. Fur-

thermore, others suggest that work values are a core

means by which individuals judge their fit, and candi-

dates are attracted to organizations that exhibit char-

acteristics similar to their own, and in turn organiza-

tions tend to select employees who are similar to the

organization, which is a similar idea to Schneider’s

Attraction-Selection-Attrition (ASA) framework, that

identifies a similar fit at the personal level between

the candidate and the organization (Schneider et al.,

1995). Value congruence has become widely ac-

cepted as the defining operationalization of P-O fit

(Kristof-Brown et al., 2005).

On a more fine-grained level however the specific

roles within an organization pose a variety of specific

requirements (e.g. managerial role requirements are

very different from the requirements of a production

line worker). Using a large sample Lounsbury et al.

looked for a distinctive managerial profile that differ-

entiated them from workers in other occupations. The

investigation revealed a distinctive managerial per-

sonality profile in terms of the Big Five and other

measures of personality. In the following 9 person-

ality trait facets managers reached higher scores than

SECRYPT 2018 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

212

non-managers: Extraversion, Assertiveness, Consci-

entiousness, Emotional Stability, Agreeableness, Op-

timism, Work Drive, Customer Service Orientation,

Openness. These results have practical implications

from the personnel selection perspective to guide the

search for candidates who possess the necessary traits

to increase the person-organization fit required for

specific job types (Lounsbury et al., 2016).

Knafo and Sagiv examined the relationship be-

tween several occupations and the value profiles of

the individuals working in the respective roles. From

the different work environments, the enterprising en-

vironment is the one that is mostly characterized by

material and concrete goals, and requires one to lead,

convince or manipulate others in order to achieve de-

sired organizational and financial goals. According

to the hypothesis Power and Achievement values are

most compatible with these requirements, while the

enterprising environment would inhibit the expres-

sion of Benevolence and Universalism values. The

occupations that were examined and most closely re-

sembled the enterprising environment were: manager,

banker, financial advisor. The results showed a strong

positive correlation between the enterprising occupa-

tion and both Power and Achievement values, while a

negative correlation was observed in relation to Uni-

versalism values. The study successfully differenti-

ated occupations based on the dominant values that

are required in each particular field, thus providing

further evidence about a selection bias in place.

In summary these research results suggest some

of the mechanisms by which individuals with certain

traits or characteristics are selected for specific jobs,

first by their own attraction to these positions, and fur-

thermore by the active involvement of the recruiters.

2.2 Conflicting Incentives Risk Analysis

The relevance of focusing on the motivation of

stakeholders is recognized in the Conflicting Incen-

tives Risk Analysis (CIRA) method (Rajbhandari and

Snekkenes, 2013). The method identifies stakehold-

ers (i.e. individuals), the actions that can be taken

by these stakeholders and the consequences of the ac-

tions. A stakeholder is always an individual who has

interest in taking a certain action within the scope of

the analysis. The procedure distinguishes between

two types of stakeholders: Strategy owner (the per-

son who is capable of executing an action) and the

Risk owner (whose perspective is taken - the person at

risk). At the core of the method is the economic con-

cept of utility, which captures the benefit by imple-

menting a strategy for each stakeholder. The cumula-

tive utility encompasses several utility factors, each

representing valuable aspects for the corresponding

stakeholders, thus modelling an individual’s motiva-

tion. Two types of risks are identified in the method:

Threat risk relates to the perceived decrease in the to-

tal utility for the risk owner, and Opportunity Risk re-

lates to the lack of potential increase of utility because

the strategy owner is not motivated to take actions that

would be beneficial for the Risk owner. Therefore

risk is conceptualized as a misalignment of incen-

tives between these two classes of stakeholders, and

risk identification is concerned with uncovering activ-

ities that would be beneficial for the Strategy owner

while being potentially harmful for the Risk owner

(Snekkenes, 2013). Therefore, threat risk closely re-

sembles the concept of moral hazard as it captures

a wide range of behaviors that are beneficial for one

party and detrimental for another (i.e. strategy owner

inflicting negative externalities on the risk owner - in-

creasing one’s utility, while causing a decrease in the

utility of someone else) (Dembe and Boden, 2000).

This study focuses on Threat risks that can be at-

tributed to the motivation of key decision makers.

2.3 Theory of Basic Human Values

The theory of basic human values by Schwartz

(Schwartz, 1994) identifies 10 distinct values that

are universally recognized across various cultures and

provide a unified and comprehensive view on the mo-

tivation of individuals. Values both represent desir-

able end goals and prescribe desirable ways of acting.

Schwartz summarizes the six core features that char-

acterize values:

• Values are beliefs linked to affect.

• Values refer to desirable goals that motivate ac-

tion.

• Values transcend specific actions and situations.

• Values serve as standards or criteria.

• Values are ordered by importance.

• The relative importance of multiple values guide

action.

Furthermore, all 10 distinct values in the theory

capture one of the three key motivational aspects that

are grounded in universal requirements of human ex-

istence: needs of individuals as biological organisms,

requisites of coordinated social interaction, and sur-

vival and welfare needs of groups. Values serve as

an internal compass guiding behavior, given that the

decision context or situation activates the relevant val-

ues. The values form a circular structure which cap-

ture a motivational continuum, where adjacent values

Unobtrusive Psychological Profiling for Risk Analysis

213

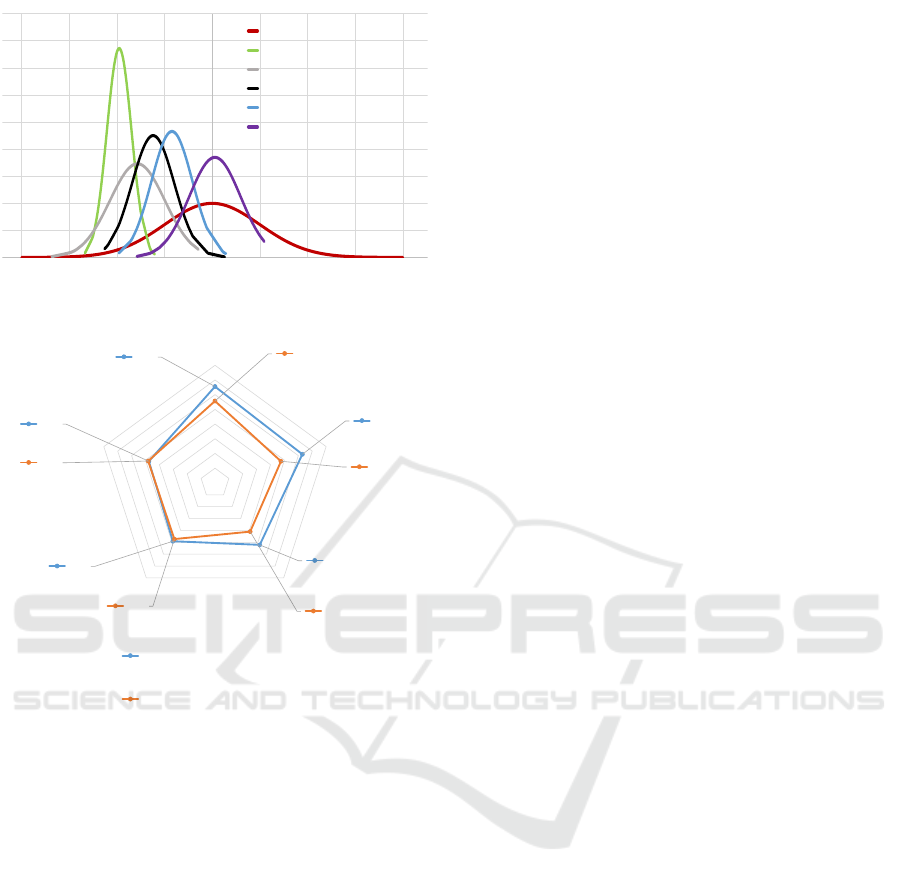

Figure 1: Circular value structure, with 4 higher dimensions

comprising of the 10 basic human values.

are compatible with each other, while opposing val-

ues are in conflict. The ten values are grouped under 4

higher dimensions as represented by Fig 1 (Schwartz,

2012).

The link between values and specific individ-

ual behaviors is a surprisingly neglected area of in-

quiry, and researchers show little agreement about

the strength of the value-behavior relationship. On

one end of the spectrum are researchers claiming that

values guide behavior (Rokeach, 1973), while others

claim that values rarely guide behaviors and not for

most people (McClelland, 1987). The behavior guid-

ing aspect of values was investigated by Bardi and

Schwartz in order to clarify the role of values in the

expression of behaviors (Bardi and Schwartz, 2003).

Their results suggest that values guide a range of be-

haviors, when the frequency of value expressive be-

haviors are investigated. A detailed analysis showed

that Stimulation and Tradition values correlate highly

with corresponding behaviors, while Hedonism, Self-

direction, Universalism, and Power values showed di-

minishing associations. Security, Conformity, Benev-

olence and Achievement values showed only weak

correlations with the behaviors that are expressive of

them. Based on these findings the predictive utility of

values is limited in a few ways: values are useful for

predicting the behavior when value-expressive behav-

iors are clearly defined and a selection is made from

a predefined set of options (e.g political party prefer-

ences and choosing university courses (Schwartz and

Bardi, 2001)). However, it is acknowledged in the

theory that most actions are expressive of more than

one value, and that the value structure that an indi-

vidual holds modifies his/her perception giving rise

to ambiguous interpretations of the same situation.

Therefore, the correspondence between values and

actions is expected to be highest in case of single de-

cisions expressing Tradition and Stimulation values,

and lower in other cases.

2.4 IBM Watson Personality Insights

Personality Insights (PI) is part of IBM’s artificial in-

telligence platform called Watson. Previously known

for defeating the top human players in Jeopardy, the

service these days is a comprehensive set of artificial

intelligence solutions available for the consumer mar-

ket. The service is utilized in a wide range of fields

including health care, weather forecast, electric load

optimization, etc. The PI utilizes advanced machine

learning solutions to uncover an individual’s psycho-

logical characteristics based on texts produced by the

person. The PI service’s main use cases involve tar-

geted marketing, customer care services, automated

personalized interactions, among several others. The

service produces profiles based on four different mod-

els of individual differences:

1. Big five personality model - one of the most

widely investigated and accepted model of per-

sonality that captures five major dimensions about

one’s personality. These characteristics describe

relatively stable behavioral tendencies and modes

of experiences.

2. Needs - based on the earliest investigations into

human motivation capturing an individual’s high-

level desires.

3. Basic human values - values capture both desir-

able goals that people pursue and standards of act-

ing, thus providing a summary about what are the

underlying motivations behind one’s actions.

4. Consumption preferences - optimized for predict-

ing the user’s likelihood for buying a certain prod-

uct or engaging in different activities.

In terms of the Value profiles, the service cal-

culates the four higher-level profiles: Conserva-

tion, Openness to change, Self-enhancement, Self-

transcendence and Hedonism as separate values,

whereas the original formulation by Schwartz iden-

tifies four major ones, with Hedonism being part of

either Openness to change or Self-enhancement. For

each personality characteristic the PI computes two

scores: percentile scores and raw scores. “To compute

the percentile scores, IBM collected a very large data

set of Twitter users (one million users for English,

200,000 users for Korean, 100,000 users for each of

Arabic and Japanese, and 80,000 users for Spanish)

and computed their personality portraits. IBM then

SECRYPT 2018 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

214

compared the raw scores of each computed profile to

the distribution of profiles from those data sets to de-

termine the percentiles. The service computes nor-

malized scores by comparing the raw score for the

author’s text with results from a sample population”

(IBM, 2017). While the percentile scores can provide

insights about the value distributions of a sample in

relation to the original sample it is not well-suited to

characterize an individual’s profile for the purpose of

choice predictions, because the value structure rela-

tive to a sample population does not necessarily cor-

respond to the individual’s own value priorities. To

allow comparison between different populations and

scenarios the service also provides raw scores that re-

flect a score the person would get when completing a

personality test. Therefore, raw scores are more suit-

able to compare with populations with existing means

and standard deviations, and to analyze value priori-

ties within and among individuals.

3 METHODS

3.1 Participants

The convenience sampling method produced the fi-

nal sample that consisted of 116 CEOs (105 male, 11

female), aged between 34-95 years (M = 59.41, SD =

9.23) with sufficient amount of texts for running accu-

rate analysis by the IBM Watson service. The amount

of text available for the individuals ranged between

264-11384 words (M = 3830.98, SD = 1672.28). The

majority of the subjects were born in the USA (N

= 52.6%), followed by India (N = 12.9%), United

Kingdom (N = 6.9%) and 21 other countries (N =

27.6%). 84.4% of the sample had at least bache-

lor or equivalent level degrees. The total compen-

sation for the CEOs in year 2016 ranged between

$45,936 - $46,968,924 (M = $15,988,276.78, SD

= $10,600,982.56) according to publicly available

sources (Salary.com, 2004).

3.2 Data Collection

In order to answer the Research Questions it was nec-

essary to run an initial pilot study to assess the feasi-

bility of the data collection activity. During the pilot

study the first step involved the identification of rele-

vant sources of data. To this end the Wikipedia article

on the List of chief executive officers of notable com-

panies was used that contains CEOs with diverse na-

tional and industrial backgrounds (Wikipedia, 2004).

At the time of the start of the data collection the list

consisted of 174 subjects. The second step involved

the identification of suitable sources of information

that could be linked to the individual and provided

sufficient input to the Watson service for achieving

it’s maximum precision (3000 words/subject is rec-

ommended by the service description). In this phase

we relied on video interviews, interviews published in

online newspapers, news articles, company commu-

nications and social media profiles. Although it was

possible to collect the necessary amount of data from

the individuals, the procedure was not feasible due to

high diversity of contexts, the uncertainty related to

the actual author of the texts and the time needed to

collect the data, so in the final data collection phase

this procedure was modified in the following way:

• The search was restricted to videos published on

YouTube that (a) were in English, (b) the sub-

ject could be clearly identified while providing

his thoughts, and (c) were supplemented with cap-

tions.

• The search then was executed by using the sub-

ject’s name with the following additional terms (in

the same order): - interview, talk, presentation. In

case the first search term did not provide sufficient

amount of text the next one was used.

• In order to achieve as high validity as possible for

the analysis we aimed at collecting mainly inter-

views and discussions that are more spontaneous

and reflective in content (thus we aimed at min-

imizing the reliance on well-rehearsed communi-

cations or texts written by other parties for presen-

tation purposes).

• Each video was carefully observed in real time

to check the accuracy of the captions and to en-

sure that only the subject’s utterances are ex-

tracted for analysis, while omitting any noise (in-

terviewer/audience questions, false transcriptions,

etc.)

• A fresh install of Google Chrome was utilized in

incognito mode, to keep personalized search re-

sults to a minimum and to maximize the repro-

ducibility of the search results.

After a sufficient amount of text was collected

from the subjects, the texts were submitted to the Wat-

son PI service, that produced a profile for each indi-

vidual.

For the purpose of a more fine grained analysis,

CEOs that have been associated with various deci-

sions leading to moral hazard have been identified

in the current sample. To this end extensive web

searches were conducted with the name of the individ-

ual and the additional search term (e.g. fraud, scandal,

corruption). The first 20 search results were screened

Unobtrusive Psychological Profiling for Risk Analysis

215

for each subject in order to identify possible associa-

tions with moral hazard. Using a broad sense of the

moral hazard concept, any behavior was eligible for

inclusion when it had a negative effect on the repu-

tation of the organization by drawing public attention

to the underlying misconduct (irrespective of the na-

ture of the misconduct) and the behaviors were con-

ducted under the administration of the CEO in focus.

The included activities covered a wide range of be-

haviors (e.g. bribery of public officials, tax evasion,

accounting fraud, insider deals, ethical misconduct,

etc.). The procedure resulted in the identification of

31 CEOs (26.7% of the sample) associated with un-

desirable behavior, and enabled the value profile com-

parisons between the two classes of CEOs.

4 RESULTS

4.1 A Note on the Concept of Difference

It is important to note that the term ‘difference‘ can

have several meanings. In order to characterize the

differences we utilized several approaches. In the first

approach the percentile scores derived from the Wat-

son PI service were used, that inherently contains a

comparison between the subject’s results and the orig-

inal sample’s distribution, on which the service was

validated (N = 1 million users) (IBM, 2017). This

view provides an understanding about the CEO sam-

ple’s overall position for each value dimension. Due

to the meaning of percentile scores certain, expecta-

tions can be calculated on the number of value profiles

that are expected to fall within 1 SD from the means.

These assumptions were tested in the first procedure.

A second approach utilizes the raw scores derived

from the PI service, which are suggested to be equiv-

alent to the scores one would get when completing an

actual psychometric test (in this case any variant of

the several existing Schwartz value surveys (Schwartz

et al., 2001)). These scores can be compared to re-

sults established in different populations, therefore

are more suitable for comparing results obtained by

other researchers. The second procedure followed

this line of reasoning, and was mainly concerned in

identifying a difference in the rank ordering of val-

ues between CEOs and the general population. In this

sense, any difference in the ordering of the values (to

most important to least important) would be indicative

of a marked difference between the group of CEOs

and the general population.

However, rank orders in isolation do not provide

all the necessary information about and individual’s

trade-off decisions, since a preference reversal (i.e.

choice of different strategies with the same value or-

ders among individuals) is possible, while maintain-

ing the same value order. In light of this fact and in

accordance with the theory’s concepts it is the relative

importance of values that should be analyzed when

certain decisions are weighed against each other. Fur-

thermore, since many studies use different instru-

ments and methodologies for assessing value profiles

or use different levels of analysis, it was necessary

to enhance the compatibility and comparability of re-

search findings (Lindeman and Verkasalo, 2005). To

this end, in the third procedure the raw scores were

summed across all values, and each score was multi-

plied by the Sum

−1

, to quantify each value’s contri-

bution to the overall utility (=1). The same procedure

was carried out for research results that served as ref-

erence for the comparisons. This approach provides

the assessment of an individual’s value structure in-

dependent of the instrument used for conducting the

profiling.

4.2 Comparison with Watson PI Sample

The first procedures aimed at detecting the existence

of a bias among the percentile scores among the five

higher level values. The percentile scores were trans-

formed by mapping them to a standard normal dis-

tribution, then for each value Kolmogorov-Smirnov

tests were conducted with a reference standard nor-

mal distribution (M = 0, SD = 1) to assess whether

the value score would be drawn from the same distri-

butions. The results indicate that all distributions are

significantly different from the reference normal dis-

tribution. All five, one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov

tests rejected the null hypothesis that the data fol-

lowed the normal distribution for variables: Conser-

vation (D = .741), Openness to change (D = .194),

Hedonism (D = .916), Self-enhancement (D = .657)

and Self-transcendence (D = .534), N = 116 each, and

p > .05 each). Fig 2 shows the distribution of all the

values based on the transformed percentile scores.

4.3 Comparison with National

Representative Samples

In the following procedure the raw scores have been

transformed to match with the original scale’s scoring

system used in the studies conducted by Schwartz and

Bardi (Schwartz and Bardi, 2001). The representative

or near-representative samples provide the necessary

comparison that allows for a more detailed descrip-

tion of the value profiles. Fig 3 shows the general

population’s value priorities compared with the CEO

value priorities based on the raw scores.

SECRYPT 2018 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

216

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5

Standard normal distribution

Hedonism

Conservation

Openness to change

Self-enhancement

Self-transcendence

Figure 2: Distribution of CEO value percentiles relative to

reference standard distribution.

5.55

5.29

4.22

3.91

3.76

4.57

3.75

3.10

3.73

3.81

-1.00

0.00

1.00

2.00

3.00

4.00

5.00

6.00

7.00

Self-transcendence

Openness to change

Self-enhancementHedonism

Conservation

Adjusted CEO mean raw scores

Mean scores based on 13 national

representative samples

Figure 3: Value profile comparison between sample of

CEOs and representative samples covering 13 nations.

4.4 Analysis of CEO Value Profile

For the purpose of individual level choice prediction

it is the relative importance among the values guiding

the actions, therefore for each behavior the relation of

all the values has to be considered. To this end the

CEO group’s average profile is analyzed in terms of

the relative importances among values based on the

procedure previously described. Additionally, based

on the previous classification of individuals with their

association with moral hazard, five independent sam-

ples t-tests were conducted on the raw scores to com-

pare the importance of each value for the two classes

of CEOs to detect any difference that might be in-

dicative of negative organizational outcomes. Table

1 shows the results of the performed t-tests. Open-

ness to change and Conservation values were signifi-

cantly different between the two groups. Specifically,

a slight decrease in both of these two values is associ-

ated with a value profile corresponding to undesirable

behaviors. Fig 4 illustrates the relative importance

scores among the CEO sample, the CEO sub-sample

associated with moral hazards and the general popu-

lation. Rank order of the values is marked above the

bars where the CEO sample’s ranking is followed by

the general population’s rank for each value. The *

symbol marks the values which have been identified

to be significantly different among the CEO groups,

based on the previous analysis.

5 DISCUSSION

This study aimed at exploring the basic human value

structure of CEOs by using text-based personality in-

ferences using the IBM Watson PI service. Our re-

sults suggest that there is a selection bias that mani-

fests itself through the individual value profiles. Ac-

cording to the results there are clearly identifiable

differences among the universally established value

structures in the general population and the sample of

CEOs. This marked difference is interpreted as an ev-

idence of the selection bias within leading positions

and the consequences of this distinct value structure

are discussed in this section, additionally identifying

further research directions.

The first remarkable difference among the value

profiles is manifested in the difference between the

rank order of values among CEOs and the general

population. While Self-transcendence values (i.e.

care for the welfare of closely related others, as well

as care for all the people and for nature) are most im-

portant for both groups the similarities between CEOs

and non-CEOs end at this point.

Openness to change (i.e. self-direction, indepen-

dence, creating, stimulation and seeking out chal-

lenges) ranks as the second most important value

in case of corporate leaders, while it is the sec-

ond least important motivational factor for the pop-

ulation. Openness to change and Conservation val-

ues can be found at opposing sides of the moti-

vational circumplex, which reflects that decisions

that promote the obtaining of a particular value in-

hibit the simultaneous fulfillment of the competing

value. Therefore a high priority given to Openness

to change values would result in choices increas-

ing novelty and chances for expressions of indepen-

dent action at the expense of maintaining stability

and stability. Self-enhancement values (i.e. expres-

sion of competence, achievement of status and con-

trol over others) rank at the third position for CEOs,

while it is the least important motivational force in

the general population. Although one might expect

that leaders of world-leading organizations (express-

Unobtrusive Psychological Profiling for Risk Analysis

217

Table 1: Results of the independent samples t-tests among two CEO groups.

CEO raw scores associ-

ated with moral hazard

(n = 31)

CEO raw scores not as-

sociated with moral haz-

ard (n = 85)

M SD M SD t-test

Values

Self-transcendence 0.82 0.01 0.82 0.01 ns

Openness to change 0.78 0.02 0.79 0.02 2.20*

Self-enhancement 0.65 0.02 0.65 0.02 ns

Hedonism 0.61 0.01 0.61 0.02 ns

Conservation 0.59 0.02 0.60 0.03 2.07*

*p < .05; two-tailed.

Note. M = Mean. SD = Standard Deviation

0.236

0.227

0.188

0.177

0.172

0.237

0.226

0.188

0.178

0.170

0.241

0.198

0.164

0.197

0.201

0.000

0.050

0.100

0.150

0.200

0.250

0.300

Self-transcendence Openness to change* Self-enhancement Hedonism Conservation*

CEOs not associated with moral hazard CEOs associated with moral hazard Cross cultural group

Value priorities: (1) CEO - (2) General population

1. 1. 2. 4.

3. 5. 4. 3. 5. 2.

* significant difference between the two CEO groups

Figure 4: Comparison between the relative importance of values among two groups of CEOs and general population.

ing power and achievement values) would be mainly

motivated by Self-enhancement values at the expense

of Self-transcendence values, these results contradict

this expectation. The rank order difference of Self-

enhancement values between non-CEOs (5.) and

CEOs (3.) however clearly expresses their preference

for high social status and prestige.

While for non-CEOs, the second most important

motivational tendencies relate to Conservation values

(i.e. security, safety of self and of society, restraint

of actions likely to harm others, respect for customs),

these aspects of behavior seem much less important

to leaders, as it ranks the lowest on the their mo-

tivational hierarchy, indicating that actions promot-

ing Conservation values have a much lower intrinsic

motivational effect (e.g. in order to make an action

appear at least as rewarding as an action expressing

Openness to change values it has to be incentivized

much more externally).

The relative importance of values matches closely

with the various Enterprising value profiles identified

by Knafo and Sagiv, placing CEOs close to other

occupations characterized by material and concrete

goals, leading and manipulating people (occupations

within the category that have similar value profiles:

financial advisor, banker, manager) (Knafo and Sagiv,

2004).

The final analysis uncovered differences in the

SECRYPT 2018 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

218

value profiles of two CEO groups when their associa-

tion with moral hazard is taken into account. Specif-

ically, a slight, but significantly lower relative impor-

tance attributed to Openness to change and Conser-

vation values was associated with various undesirable

behaviors that can be detrimental to the reputation of

the organization lead by the particular CEOs.

A limitation of the present study is the small sam-

ple size, which can be extended in further studies,

since the method of analyzing value profiles by using

the Watson PI service is a feasible method for gather-

ing information about the motivation of decision mak-

ers for the purpose of risk analysis.

Furthermore, a more detailed description and clas-

sification of the various forms of moral hazard would

have the potential to elaborate on the connection be-

tween the particular value profile displayed by a strat-

egy owner and the level of impact that was inflicted

upon the organization, to have a better assessment of

the risks relating to particular individuals.

Future work will focus on the issue of how other

observable features (e.g. gender, age, occupational

choice (Dohmen et al., 2011), consumer preferences

(Kassarjian, 1971) or various forms of online behav-

ior with digital footprints (Kosinski et al., 2013), etc.)

can be utilized for the construction of psychological

profiles suitable for predicting behavior in the context

of risk analysis. In particular, it is crucial to identify

observable features that can significantly reduce the

uncertainty associated with an observable’s ability to

convey information about a specific motivational trait.

6 CONCLUSION

In summary, this exploratory study is the first one pre-

senting how publicly observable traces of individuals

can be used for constructing a psychological profile

suitable for risk analysis. The study presented a de-

tailed description of the procedures necessary for un-

covering the motivational structure of leaders of vari-

ous organizations utilizing an unobtrusive psycholog-

ical profiling method. The procedure was conducted

by means of textual analysis based on publicly avail-

able written or spoken statements by the subject, and

the results supported the hypothesis that key decision

makers’ motivation is significantly different from that

of the general population that is interpreted as evi-

dence of a meaningful selection bias. Presenting the

motivational structure in terms of basic human values

in a form that is independent of the instruments uti-

lized provides an useful input for comparing different

stakeholder’s motivation, and for analyzing a poten-

tial candidate’s similarity with the profiles established

here. Finally, the distinct value profile associated with

undesirable behaviors can be helpful during the selec-

tion of candidates for a leading position by the board

of directors in determining the potential risks result-

ing from the employment of a specific individual.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by the project IoT-

Sec – Security in IoT for Smart Grids, with number

248113/O70 part of the IKTPLUSS program funded

by the Norwegian Research Council.

REFERENCES

Anderson, R. and Moore, T. (2009). Information security:

where computer science, economics and psychology

meet. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Soci-

ety of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engi-

neering Sciences, 367(1898):2717–2727.

Babiak, P., Neumann, C. S., and Hare, R. D. (2010). Corpo-

rate psychopathy: Talking the walk. Behavioral sci-

ences & the law, 28(2):174–193.

Bardi, A. and Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Values and behavior:

Strength and structure of relations. Personality and

social psychology bulletin, 29(10):1207–1220.

Boddy, C. R. (2005). The implications of corporate psy-

chopaths for business and society: An initial exam-

ination and a call to arms. Australasian Journal of

Business and Behavioural Sciences, 1(2):30–40.

Cohan, J. A. (2002). " i didn’t know" and" i was only doing

my job": Has corporate governance careened out of

control? a case study of enron’s information myopia.

Journal of Business Ethics, 40(3):275–299.

Dembe, A. E. and Boden, L. I. (2000). Moral hazard:

a question of morality? New Solutions: A Jour-

nal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy,

10(3):257–279.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp,

J., and Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk at-

titudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral

consequences. Journal of the European Economic As-

sociation, 9(3):522–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assess-

ment and review. Academy of management review,

14(1):57–74.

Fosso, O. B., Molinas, M., Sand, K., and Coldevin,

G. H. (2014). Moving towards the smart grid: The

norwegian case. In Power Electronics Conference

(IPEC-Hiroshima 2014-ECCE-ASIA), 2014 Interna-

tional, pages 1861–1867. IEEE.

IBM (2017). The science behind the service. [Online; ac-

cessed 14-February-2018].

Kajonius, P. J., Persson, B. N., and Jonason, P. K. (2015).

Hedonism, achievement, and power: Universal values

Unobtrusive Psychological Profiling for Risk Analysis

219

that characterize the dark triad. Personality and Indi-

vidual Differences, 77:173–178.

Kassarjian, H. H. (1971). Personality and consumer behav-

ior: A review. Journal of marketing Research, pages

409–418.

Knafo, A. and Sagiv, L. (2004). Values and work environ-

ment: Mapping 32 occupations. European Journal of

Psychology of Education, 19(3):255–273.

Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., and Graepel, T. (2013). Pri-

vate traits and attributes are predictable from digital

records of human behavior. Proceedings of the Na-

tional Academy of Sciences, 110(15):5802–5805.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., and Johnson,

E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’fit at work:

A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization,

person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel

psychology, 58(2):281–342.

Lindeman, M. and Verkasalo, M. (2005). Measuring val-

ues with the short schwartz’s value survey. Journal of

personality assessment, 85(2):170–178.

Lounsbury, J. W., Sundstrom, E. D., Gibson, L. W., Love-

land, J. M., and Drost, A. W. (2016). Core personality

traits of managers. Journal of Managerial Psychol-

ogy, 31(2):434–450.

McClelland, D. C. (1987). Human motivation. CUP

Archive.

Morley, M. J. (2007). Person-organization fit. Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 22(2):109–117.

Rajbhandari, L. and Snekkenes, E. (2012). Intended ac-

tions: Risk is conflicting incentives. Information Se-

curity, pages 370–386.

Rajbhandari, L. and Snekkenes, E. (2013). Using the con-

flicting incentives risk analysis method. In IFIP Inter-

national Information Security Conference, pages 315–

329. Springer.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free

press.

Salary.com (2004). Executive compensation it starts with

the ceo. [Online; accessed 14-February-2018].

Schneider, B., GOLDSTIEIN, H. W., and Smith, D. B.

(1995). The asa framework: An update. Personnel

psychology, 48(4):747–773.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the

structure and contents of human values? Journal of

social issues, 50(4):19–45.

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the schwartz theory

of basic values. Online readings in Psychology and

Culture, 2(1):11.

Schwartz, S. H. and Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierar-

chies across cultures: Taking a similarities perspec-

tive. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 32(3):268–

290.

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S.,

Harris, M., and Owens, V. (2001). Extending the

cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human

values with a different method of measurement. Jour-

nal of cross-cultural psychology, 32(5):519–542.

Snekkenes, E. (2013). Position paper: Privacy risk analy-

sis is about understanding conflicting incentives. In

IFIP Working Conference on Policies and Research in

Identity Management, pages 100–103. Springer.

Soltani, B. (2014). The anatomy of corporate fraud: A com-

parative analysis of high profile american and euro-

pean corporate scandals. Journal of business ethics,

120(2):251–274.

Van Peursem, K. A., Zhou, M., Flood, T., and Buttimore,

J. (2007). Three cases of corporate fraud: an audit

perspective.

Wikipedia (2004). List of chief executive officers

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. [Online; accessed

06-December-2017].

SECRYPT 2018 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

220