Crypto-democracy: A Decentralized Voting Scheme using Blockchain

Technology

Gautam Srivastava

1

, Ashutosh Dhar Dwivedi

2

and Rajani Singh

2,3

1

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Brandon University, Brandon, Manitoba, Canada

2

Institute of Computer Science, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland

3

Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics, and Mechanics, University of Warsaw, Poland

Keywords:

Blockchain Voting, Graphs, Voting Schemes, PHANTOM, Distributed System, Cryptocurrency.

Abstract:

A fraudulent election is one of the biggest problems of the contemporaneity in most countries. Even the

world’s largest democracies like India, United States, and Japan still suffer from a flawed electoral system.

Vote rigging, hacking of the EVM (Electronic voting machine), election manipulation, and polling booth

capturing are the major issues in the current voting system. This fallacious election process calls voting

systems into question. With the current Cambridge Analytica scandal a hot topic around the world, it brings

the validity of current voting systems into question. In this paper, we investigate the problems in the election

voting systems and propose a novel voting model which can resolve these issues. We use a recently introduced

blockchain based protocol called PHANTOM, which uses a directed acyclic graph of blocks, also known as

blockDAG, to generalize the initial blockchain technology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Some countries have already taken the initiative to im-

prove their voting system by using blockchain tech-

nology (Nakamoto, 2008) — a decentralized peer to

peer network accompanied by a public ledger. The

inability to change or delete information from blocks

makes the blockchain the best technology for vot-

ing systems. However, questions surrounding se-

curity and scalability of the voting system using

blockchain methodology still need to be answered.

In a blockchain protocol, when a miner (responsible

node for maintaining the blocks) extends the chain

with a new block, it propagates in time to all hon-

est nodes before the next one is created. The prop-

agation of these long, data and electricity intensive

blockchains brings on the problems of the proto-

col that we have seen with many cryptocurrencies.

Namely, large electricity usage, large blockchains,

and very slow computational speeds. In the more than

likely case when block creation rates are sped up or

block size increased, we will most definitely see these

problems grow in an exponential nature. Therefore, to

apply classic blockchain techniques to voting appli-

cations for larger democratic countries with massive

populations is not by any means efficient or viable.

Apart from the technical considerations, vote count-

ing strategies also play an important role in any elec-

tion process. Game theorists have suggested various

types of voting schemes, each of them having their

benefits and drawbacks. Vote counting schemes that

are currently widely used are:

1. Plurality voting — where each voter is allowed to

vote for only one candidate and whoever gets the

most votes is elected.

2. Ranked voting — Instead of selecting only one

candidate, voters rank all the candidates according

to their preferences from most preferred to least.

Each country has different political and local en-

vironment.

Moreover, the process to actually choose a good

vote counting scheme based on country of election is

another challenge altogether. Recently we have seen a

major scandal hit the worldwide press involving Cam-

bridge Analytica (Greenfield, 2018). The data ana-

lytic firm used personal information harvested from

more than 50 million Facebook profiles without per-

mission to build a system that could target US vot-

ers with personalised political advertisements based

on their psychological profile. This scandal has

brought the voting system of a major international

democracy, the U.S.A., into question. The worldwide

scandal eventually led to the firm having to declare

bankruptcy.

508

Srivastava, G., Dwivedi, A. and Singh, R.

Crypto-democracy: A Decentralized Voting Scheme using Blockchain Technology.

DOI: 10.5220/0006881905080513

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2018) - Volume 2: SECRYPT, pages 508-513

ISBN: 978-989-758-319-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Related Work

In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto invented the basis

for what we now know as blockchain technology

(Nakamoto, 2008). The core concepts for this system

were used in many cryptocurrencies and other appli-

cations, with the reach of its applicable side still not

fully known. Built on the blockchain technology of

Nakamoto was a protocol called PHANTOM, which

we build on here (Sompolinsky and Zohar, 2018).

PHANTOM has been proven to be secure under any

throughput that the network itself can support, which

makes it prime for use in voting systems where voters

can number in the millions.

Many digital voting system are currently in use

around the world. In 2005, Estonia started the first on-

line voting system for municipal elections. In 2007,

internet voting was also used in the Estonian parlia-

mentary election. In 2015, they used an i-voting sys-

tem (Valimised, 2015) for the parliamentary election

system and 30.5% votes were made through i-voting.

In 2015, the state of Virginia in tne United States

of America also implemented a blockchain based so-

lution to vote using Follow My Vote (Vote, 2017).

In this blockchain implementation, voters installed a

”voting booth” on a computer or smartphone. But

there were too many flaws in this implementation and

therefore the Follow My Vote project is still active but

has lost funding.

In 2016, Kaspersky Labs and Economist newspa-

per (Jennifer Bondarchuk, 2017) organized a com-

petition where teams from the United States and

United Kingdom had to implement voting system us-

ing blockchain. The Votebook team from New York

University, U.S.A. came in first place who offered the

most effective case study on how a blockchain voting

system might look.

In 2014, Lalley and Weyl proposed that

blockchain lowers disorder and dictatorship costs of

the voting and electoral process (Lalley and Weyl,

2014). In addition to efficiency gains, this techno-

logical progress has implications for decentralized

institutions of voting. One application they proposed

is Quadratic Voting (QV), which was further studied

by (Posner and Weyl, 2015). Voters making a binary

decision purchase votes from a centralized clearing

house, paying the square of the number of votes

purchased. They show that this process is both

efficient and applicable to modern voting. Last year,

it was suggested that

Quadratic voting is the most important idea

for law and public policy that has emerged

from economics in (at least) the last ten years

(Allen et al., 2017)

We will further some of the initial ideas revolving

around blockchain voting in this paper to a decentral-

ized system that is efficient, secure, and most impor-

tantly realizable for large democracies.

1.1 Drawbacks and Security Issues

Security of digital voting is always a big problem in

voting systems. During these digital voting elections,

researchers identified many potential security risks.

Such risks could be malware in the client machine

that can change a vote for a different candidate or,

another possibility is an attacker can directly infect

servers. However, a model with a blockchain voting

system could prevent these issues but for larger demo-

cratic countries having massive populations and large

geographical area, blockchain alone is not enough of

a solution because of its slow computational speed.

Some countries are also fighting with other prob-

lems in voting systems like illiteracy, threatening vot-

ers, and booth capturing. Therefore, using a current

blockchain voting model is not enough to fight against

a flawed election system.

2 OUR SYSTEM

We break down our system into the following two

contributions:

1. In this paper, we introduce a more advanced

blockchain voting management system. Instead

of using the classic blockchain protocol, we

use the PHANTOM protocol — a protocol for

transaction confirmation that is secure under any

throughput that the network can support. PHAN-

TOM, unlike some of its predecessors, enjoys

very large transaction throughput, which is a ma-

jor downfall of many cryptocurrencies. PHAN-

TOM utilizes a Directed Acyclic Graph of blocks,

aka blockDAG, a generalization of blockchains

which better suits a setup of fast or large blocks.

PHANTOM uses a greedy algorithm on the

blockDAG to distinguish between blocks mined

properly by honest nodes and those mined by non-

cooperating nodes that deviated from the DAG

mining protocol.

2. To help alleviate the problems of booth capturing

or voter threatening, we consider the Borda count

method for vote counting which is a ranked based

voting scheme (Emerson, 2013).

Crypto-democracy: A Decentralized Voting Scheme using Blockchain Technology

509

2.1 Proposed System

We propose a model that does not replace the present

digital voting model but rather integrates new tech-

nology and other modifications in the current system.

2.2 System Requirements

1. Authentication: Votes can only be made by au-

thentic voters. In our system we do not need a

registration process. Many countries provide a

unique national identity card by using biometric

and demographic data of people. As governments

already have biometric information of people, we

use fingerprint authentication to ensure an honest

voter identity.

2. Accuracy: Every vote should be counted, must be

accurate and cannot be changed. For this purpose

we are using the PHANTOM protocol which is

more secure than blockchain. To reduce the ef-

fect of problems like polling booth capturing or

threatening voters we adopted the special voting

schemes called the Borda count method.

2.3 The PHANTOM

The basis for PHANTOM protocol is blockchain

which was invented by Satoshi Nakamoto in

(Nakamoto, 2008). Bitcoin is considered the first ap-

plication of blockchain that allows currency transac-

tions over the internet without relying on third party

financial institutions. Blockchain is an ordered data

structure consisting of blocks of transactions. The

blocks are connected with each other in the form of

chain. The first block of the chain is known as Gen-

esis. Each block consists of a Block Header, Trans-

action Counter and Transaction. The structure of

blockchain follows:

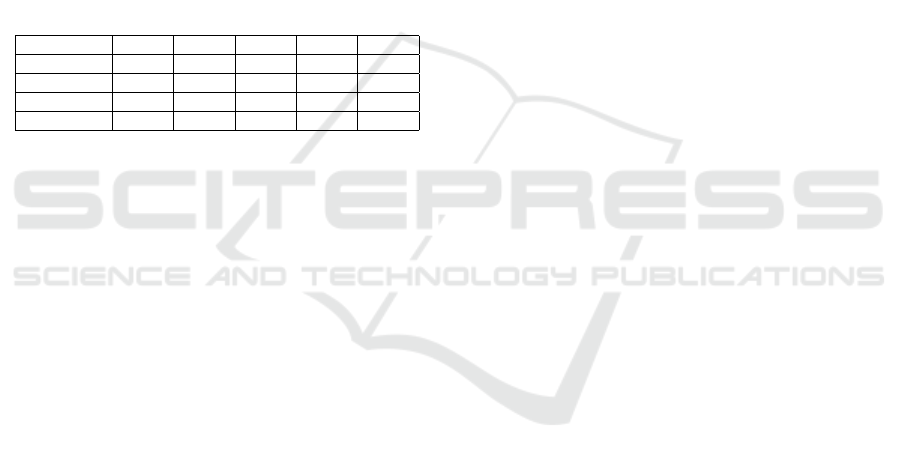

Table 1: Structure of the Blockchain.

Field Size

Block Header 80 bytes

Block Size 4 bytes

Transaction Counter 1 to 9 bytes

Transaction Depends on the transaction size

Each block in the chain is identified by a hash

in the header. The hash is unique and generated by

Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA-256). SHA takes any

size plaintext and calculates fixed size 256-bit cryp-

tographic hash. Each header contains the address of

the previous block in the chain. In blockchain, each

new transaction block is created by “miners”. Min-

ers solve difficult mathematical problems based on

hash algorithms. The solution found by this prob-

lem is called “Proof-Of-Work”. Miners could be an

honest node or dishonest node. It might also be pos-

sible that a new fake block is mined by a dishonest

node. But this requires a lot of computer efficiency to

solve proof of work, which is possible but not easy.

When a miner extends the chain with a new block,

it propagates in time to all honest nodes before the

next one is created. On average, a block is mined ev-

ery 10 minutes. So, if you perform a transaction, it

will take approximately 10 minutes to complete. The

propagation of these long, data and electricity inten-

sive blockchains bring on the problems of scalability

of the protocol and slow computational speed. There-

fore for the purpose of distributed voting for large

population countries blockchain is not a good option.

For the above reasons instead of blockchain we

are using more advance version of blockchain called

PHANTOM protocol in our model which is more se-

cure against dishonest blocks as well as fast. PHAN-

TOM, first introduced by Yonatan Sompolinsky and

Aviv Zohar in 2018, utilizes the Directed Acyclic

Graph of blocks (blockDAG) (Sompolinsky and Zo-

har, 2018). PHANTOM uses a greedy algorithm

on blockDAG to distinguish between properly mined

blocks by honest nodes and the blocks mined by non-

cooperating or dishonest nodes. These nodes are

identified as they deviate from DAG mining proto-

col. In blockDAG structure, rather than extending

a single chain, miners are instructed to reference all

blocks in the graph (that were not previously refer-

enced, i.e., leaf-blocks). PHANTOM resolves the

scalability, trade-off, security issues and guarantees a

fast voting process which makes it more general and

scalable than the classic blockchain protocol.

In PHANTOM protocol, instead of a chain the

blocks are in the form of tree structure. When cre-

ating a new block, miners only reference the tip of the

longest chain in the tree and ignore the rest.

We have divided the blocks in the form of a clus-

ter. We created 3-cluster of blocks within a given

DAG: A,B,C, D,F,G, I,J (colored blue). The prop-

erty of this cluster is, each block has at most 3 blue

blocks in an anticone. If we talk about E,H,K (col-

ored red), these blocks have more than 3 elements in

anticone. Therefore if we set parameter k = 3, this

means 4 blocks can be created within each unit of de-

lay. This is the reason PHANTOM enjoys large

transaction throughput as rather than extending a

single chain, miners in PHANTOM reference all

blocks in graph.

SECRYPT 2018 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

510

Figure 1: 3-cluster of block DAG.

2.4 Voting Mechanism and Architecture

We use a multi-tiered, decentralized distributed ledger

by dividing the protocol network into three tiers:

Figure 2: Three tier node structure.

1. National: The national tier (level 1) is the set of

nodes which are not tied to any location. At this

node, we apply the PHANTOM protocol. These

nodes are only responsible to mine transactions

and add blocks in the form of blockDAG instead

of a long chain of blocks, as shown in Figure 2.

All national nodes are connected with each other

and can communicate.

2. Constituency: The constituency also known as

electoral area is a territorial subdivision for elect-

ing members. The constituency tier (level 2) con-

tains all the nodes that are deemed to be at the

constituency level. These nodes would be di-

rectly connected to each other and to a subset of

polling stations under that constituency. A state

or province of a given country would make for a

good example of this tier.

3. Local: The local tier (leaf nodes) is a set of all

polling stations across the country. A local node

is setup to only communicate with the other lo-

cal nodes under the associated constituency node

and the constituency node itself. B1, B2...B9 rep-

resents the vote transactions by individual voters

which is transferred to upper level nodes after en-

cryption.

We are using an encryption method which is based

on public and private keys as in Figure 3. Each con-

stituency level nodes generate the key pairs. Each

constituency node has different public key. The pub-

lic key are distributed to all lower level connected

polling station nodes in Local tier under the given

constituency node. These nodes use public keys to

encrypt votes made by polling stations. As each con-

stituency has a different public key, chunks of data

under a given constituency are encrypted differently

than the other chunk of data in other constituencies.

In such case if a hacker manage to recover private

key of a particular constituency then he/she will only

be able to decrypt data under current constituency.

He/she will not be able to recover all data in other

constituency. Once the voting deadline passed, con-

stituency nodes publish the private key to decrypt the

data and count vote.

We do not encourage voting through mobile apps

or web-browsers in our model because client side

machines could be infected with malware or other

viruses. Since our voting system model also focuses

on rural areas where literacy rates may be low and vot-

ers may not be familiar with the most current modern

technologies, allowing the use of modern technology

may become detrimental. Therefore, in our model,

we emphasize that the voting should be performed by

using polling booths which will prevent such attacks.

During the voting process, the voter requires a

national identification card which includes a unique

identity number, biometric information and other re-

lated data. For example, India provides a 12-digit

unique identity number issued to all Indian residents

based on their biometric and demographic data, called

UIDAI (Unique Identification Authority of India). As

government has all the biometric and demographic in-

formation of the voters, we use fingerprint authentica-

tion to ensure an honest voter identity. Once the sys-

tem identifies that user fingerprints match, he/she is

allowed to vote.

Some countries are also facing the problem of

threatening voters to vote a particular candidate or

booth capturing. Such problems can not be com-

pletely avoided but among the various voting schemes

we suggest a particular vote counting scheme which

can avoid a complete loss of honest candidates.

Crypto-democracy: A Decentralized Voting Scheme using Blockchain Technology

511

Figure 3: Key Pair Encryption.

3 VOTE COUNTING SCHEME:

BORDA COUNT

The Borda count voting scheme is a particular type

of voting where voters rank candidates in order of

preference. This method is currently used to elect

members of the Parliament of Nauru and also by the

National Assembly of Slovenia. The Borda count

is treated as a ranked or preferential voting system.

In this method candidates score one point for being

ranked last, two for being next-to-last and so on. The

candidate who receives the most points is declared

the winner. In such cases when a voter is forced to

vote for a particular candidate, he could give the sec-

ond preference to the candidate which he/she actually

wanted. Therefore, it will not be considered a com-

pletely wasted vote of his/her candidate in the elec-

tion. If there are n number of candidates, the can-

didate with 1st preference will receive n points, can-

didates with 2nd preference will receive n − 1 points

and so on.

Table 2: Borda’s system.

Ranking Candidate Formula Points

1 A n 5

2 B n − 1 4

3 C n − 2 3

4 D n − 3 2

5 E n − 4 1

Borda count is also treated as a positional vot-

ing system as candidates receive a certain number of

points. This method is useful for problems like booth

capture. Of course, it can be understood that dishon-

est candidates can still get full points in selected areas

of election where booths have been captured by in-

fluential locals. But on the other hand, people tend

to know about such candidates and therefore he/she

will get last priority in other booths which are not

captured. The honest candidate is not getting full

points in case of captured booth but voters can choose

him/her as 2nd preferred candidate.

3.1 Borda Count Example

Let us take a real example of Borda Count Method.

Consider there are 5 voters and 4 candidates A, B, C,

D. Voters have to give votes in preferential order as

shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Borda’s voting.

Borda count Voter1 Voter2 Voter3 Voter4 Voter5

3 A B D A D

2 C C A B A

1 D D C D C

0 B A B C B

Candidate A receives 10, B receives 5, C receives

6 and D receives 9 points. Therefore A wins the

election. To calculate the points we use the following

formula:

The Borda count for A is given by: (number 1st

place votes) ∗3+(number 2nd place votes) ∗2+ (num-

ber 3rd place votes) ∗1+ (number 4th place votes)

∗0 = 2 ∗ 3 + 2 ∗ 2 + 0 ∗ 1 + 1 ∗ 0 = 6 + 4 + 0 + 0 = 10.

The Borda count for B is given by: (1st place

votes) ∗3+(2nd place votes) ∗2+ (3rd place votes)

∗1+ (4th place votes) ∗0 = 5.

The Borda count for C is given by: (1st place

votes) ∗3+(2nd place votes) ∗2+ (3rd place votes)

SECRYPT 2018 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

512

∗1+ (4th place votes) ∗0 = 6.

The Borda count for D is given by: (1st place

votes) ∗3+(2nd place votes) ∗2+ (3rd place votes)

∗1+ (4th place votes) ∗0 = 9.

Now let us take the scenario when some booths

have been captured by people or, say 3 out of 5 vot-

ers are threatened by influential candidate B to vote

for him/her. In such case if we follow the normal vot-

ing system, B will surely win the election as he will

get 3/5 votes. But, if we apply Borda count method

then he might lose the election. Consider that Voter 1,

Voter 2, Voter 3 are influenced to vote for candidate

B while they actually wish to give their vote to A. In

such cases these three voters give full points to B but

as a second choice they will give some points to A as

given in Table 4.

Table 4: Borda’s voting.

Borda count Voter1 Voter2 Voter3 Voter4 Voter5

3 B B B A D

2 A A A C C

1 D D C D A

0 C C D B B

Now in such case, candidate A receives 10, B

receives 9, C receives 5 and D receives 6 points.

Therefore, A again wins the election.

The Borda count for A is given by: (number 1st

place votes) ∗3+(number 2nd place votes) ∗2+ (num-

ber 3rd place votes) ∗1+ (number 4th place votes)

∗0 = 1 ∗ 3 + 3 ∗ 2 + 1 ∗ 1 + 0 ∗ 0 = 3 + 6 + 1 + 0 = 10.

The Borda count for B is given by: (1st

place votes) ∗3+(2nd place votes) ∗2+

(3rd place votes) ∗1+ (4th place votes)

∗0 = 3 ∗ 3 + 0 ∗ 2 + 0 ∗ 1 + 2 ∗ 0 = 9 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 9.

The Borda count for C is given by: (1st

place votes) ∗3+(2nd place votes) ∗2+

(3rd place votes) ∗1+ (4th place votes)

∗0 = 0 ∗ 3 + 2 ∗ 2 + 1 ∗ 1 + 2 ∗ 0 = 0 + 4 + 1 + 0 = 5.

The Borda count for D is given by: (1st place

votes) ∗3+(2nd place votes) ∗2+ (3rd place votes)

∗1+ (4th place votes) ∗0 = 1∗ 3+ 0∗ 2+ 3∗ 1+ 1∗ 0 =

3 + 0 + 3 + 0 = 6.

4 CONCLUSION

Our model provides an ideal voting system for those

places where voting system is suffering from the

problems plaguing today’s democracies like EVM

hacking, election manipulation and polling booth cap-

turing. This model is also ideal for rural areas

where literacy rates are low. Our system does not

use browsers, tablets or mobile devices, making it

free from virus or malware attacks. When energy

consumption and slow computational speed are ma-

jor problems, our model provides a fast, secure and

high throughput voting system compared to tradi-

tional blockchain voting schemes. Since booth cap-

turing or threatening voters are still major problems

in few countries that can not be completely solved by

any technology, we propose the vote counting scheme

Borda count which helps the preferred candidate to

win the election. As a complete package we have pro-

posed a system that is easy to implement. It will be of

interest to see how blockchain technology fits into its

many proposed applications in the years to come, and

how it can be used to further the needs of the many

people that rely on technological advancement to help

further our needs as a society.

REFERENCES

Allen, D. W., Berg, C., Lane, A. M., and Potts, J. (2017).

The economics of crypto-democracy. Linked Democ-

racy: AI for Democratic Innovation, 26th Interna-

tional Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 19

August, 2017.

Emerson, P. (2013). The original borda count and partial

voting. Social Choice and Welfare, 40(2):353–358.

Greenfield, P. (2018). Cambridge analytica: The story so

far. ”https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/

26/the-cambridge-analytica-files-the-story-so-far”.

Jennifer Bondarchuk, Alexis Serra, C. Z. (2017). Cy-

ber security case study competition- kaspersky.

”http://www.economist.com/sites/default/

files/drexel.pdf”.

Lalley, S. P. and Weyl, E. G. (2014). Quadratic voting. arXiv

preprint arXiv:1409.0264.

Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic

cash system.

Posner, E. A. and Weyl, E. G. (2015). Voting squared:

Quadratic voting in democratic politics. Vand. L. Rev.,

68:441.

Sompolinsky, Y. and Zohar, A. (2018). Phantom: A scalable

blockdag protocol. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive,

2018:104.

Valimised, I. (2015). Estonia voting systems. ”https://

www.valimised.ee/en”.

Vote, F. M. (2017). Blockchain voting:

The end to end process. follow my

vote. ”https://followmyvote.com/

blockchain-voting-the-end-to-end-process”.

Crypto-democracy: A Decentralized Voting Scheme using Blockchain Technology

513