The Evaluation of Community Participation in Basic Education

Management

Laurens Kaluge

1

1

Graduate Program of Social Studies Education, Universitas Kajuruhan.

Jalan S Supriadi 48, Malang. Indonesia

laurens@unikama.ac.id

Keywords: Community Participation, Educational Management, Mainstreaming, Program Evaluation, Basic Education.

Abstract: Community participation as an important component of educational practices had been taken place in many

projects for Indonesian basic education. This study attempted to examine how well was the community

participation in innovation programs based on projects and educational levels since the beginning of the 21st

century. Data from seven provinces, consisted of 2415 teachers and 1785 parents were analyzed

descriptively. The findings revealed that good practices of such participation covered the intensity of

involvement, community needs, community satisfaction, communication systems, and partnership between

school and community. The participation degree of these components varied among the nine projects in two

level of the basic education. While changes kept on going in education, the components never fade away,

and the findings would be of benefit as lessons learnt for the future school improvement.

1 INTRODUCTION

School is in the middle of society and can be said to

have double functioning. First, is to preserve the

positive values that exist in the community, in order

to inherit the community values that take place

properly (Bundu, 2009). Secondly, it is as an

institution that can change the values and traditions

according to the progress and demands of life and

development (Epstein, 2009). Both functions seemed

contradictory, but actually are done in the same

time. Values that are in accordance with the needs of

development remain sustainably preserved, while

the unsuitable ones must be changed. Implementing

these functions of school become the foundation of

community expectations for their progress. To be

able to perform the functions of the school

community relationship, it is expected to be in

harmony (Dreikurs, 1970). Thus, the cooperation

and mutual help between school and community are

encouraged. In addition, education emerged shared

responsibilities between schools, government, and

societies.

There are ample evidences to confirm that good

practices take place everywhere. As is known, there

are sets of good practices that have been or are being

developed by various projects, including those

funded by donors at the Ministry of Education and

Culture. At the school level, the idea of community

participation in education development and

implementation can be forms of local wisdom and

excellence (ADB 2001, ADB 2004, World Bank,

2000; Sanders, 2001; Cohen-Vogel et al., 2010;

Tunison, 2013; Cuellar and Theriot, 2017).

Since the beginning of the XXI century there had

been at least nine basic education programs in

Indonesia. These nine programs were arguably the

mainstream innovation for a number of large and

small-scale projects. These programs were known by

their unique names (Muljoatmodjo, 2000, Anam,

2006): Science Education Quality Improvement

Project (SEQIP), Creating Learning Community for

Children (CLCC), Nusa Tenggara Timur Primary

Education Partnership (NTT-PEP), Basic Education

Project (BEP), Contextual Teaching and Learning

(CTL) program, Managing Basic Education (MBE),

Decentralized Basic Education Project (DBEP),

Study on Regional Education Development and

Improvement Program sponsored by JICA (REDIP-

JICA), and Study on Regional Education

Development and Improvement Program sponsored

by Indonesian Government (REDIP-G). All the

170

Kaluge, L.

The Evaluation of Community Participation in Basic Education Management.

In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities (ANCOSH 2018) - Revitalization of Local Wisdom in Global and Competitive Era, pages 170-176

ISBN: 978-989-758-343-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

programs alluded their success and best practices,

even though none could be proclaimed as the best.

The purpose of this article to evaluate how best the

community participation in separate program that

would be the exemplar for others.

2 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

With regard to community involvement, there were

three things needed to be emphasized. First, in

general, all programs or projects developed

components of community participation. Basically,

community participation was integrated in every

element of the program (Anam, 2006, Bandur,

2011). Second, some programs explicitly mentioned

community participation, for example in MBE,

REDIP JICA and REDIP-G, DBEP, CLCC, BEP,

and NTT-PEP (Muljoatmodjo, 2004; Bandur, 2012;

USAID-Prioritas, 2016; RTI-USAID, 2004). While

in SEQIP and CTL programs, community

involvement was included in the learning process

development and was not specifically developed

through training (Zürcher, 2013; Sunarsih, et al.,

2017). Third, the forms of community participation

in each program were not exactly similar (Anam,

2006). The similarities among programs were the

establishment and operationalization of school

committee including school implementation team

(task force), community participation in developing

school development plan and budgeting, in

implementing school activities, and in monitoring

school performance. The activities were initiated

such as workshops for developing community

monitoring, regular meetings for designing

schedules, and public accountability system.

The distinctive evidences considered to be the

good practices of community participation in both

REDIP-JICA and REDIP-G were the availability of

special community supports to school through

special institution like Sub-District Educational

Development Team (SDEDT), and true ownership

of education and its quality improvement,

involvement of all types of Junior Secondary

Schools (JSS), synergic approach conducted by the

school and the SDEDT in achieving the same

objectives through different programs conducted by

each party (school and SDEDT). Whereas in MBE,

CLCC and NTT-PEP the community supported the

children development through direct interaction in

the teaching learning process, raising the community

awareness, protecting children rights, and focusing

teaching learning on health and nutrition for the

lower level of primary school in NTT-PEP (Bandur,

2011; Firman and Tola, 2008).

3 DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES

Capacity building to involve communities from the

national to the school level was reviewed as follows.

At the national level, MBE and CLCC have

similarities in the preparation of trainers to lower

levels (district level on MBE, and provincial level at

CLCC). Both covered the same content and

duration, which were six days for community-based

community participation-PAKEM. Both used a

couple of national expert trainer and facilitator.

MBE trained participants from the district. While

CLCC trained teachers, principals, supervisors and

education officials from each district and province.

The provincial level had little effect on

educational practices at lower levels due to

decentralization or district autonomy regulations.

CLCC and BEP began in the centralized era of the

country. Therefore, in the MBE and NTT-PEP

projects, capacity building at the district level was

more valuable than that at the provincial level. At

CLCC, training was consistent from national to

provincial and district levels regarding the

objectives, contents, duration, trainers, participants,

and methods. While BEP, which specifically

rehabilitated the physical parts of the schools,

organized capacity building at the provincial level

which then went down to a lower level. Community

participation in BEP dealt with the selection of

eligible school selection criteria, and established

community partnerships for school rehabilitation.

At the district level, there appeared to be some

uniqueness in terms of training goals and emphasis.

MBE concerned with school budget development

plans, but CLCC focused on TOT (training of

trainers) on school clusters, BEP on school

committee and community participation in school

management functions, and NTT-PEP on

collaboration between schools and communities

while using minimum service standards (MSS) to

prepare school plans. Consequently, the objectives

and contents of capacity building itself varied among

projects; MBE on drafting school plans and budgets;

CLCC on the capabilities and competence of

trainers; BEP on regulation, partnership, knowledge

and skills in school development; NTT-PEP on MSS

by introducing school-based management and

transparent and inclusive school committees.

Training itself spent different lengths of time.

There were held 3 days in MBE, 5 days in BEP, 6

The Evaluation of Community Participation in Basic Education Management

171

days in CLCC and NTT-PEP. The duration of time

reflected how broadly the contents were embodied

into their respective project activities. MBE was

most efficient at using time but other projects tended

to take longer to convince people for participating in

educational matters. Perhaps MBE had its own

formula for approaching the community without

losing the main points of objectives relating to local

conditions. Trainers and participants at the district

level also varied among MBE, CLCC, BEP and

NTT-PEP. The diversities were shown as follows.

The MBE trainers at the district level were district

coordinators and district facilitators supported by

national trainers, while the trainees were principals,

teachers, and supervisors. The CLCC trainers were

those who had passed the TOT at the provincial

level, and the participants were teachers. In BEP, the

trainers were technical assistants from Jakarta, and

educational management experts from the district,

district manager, head of district education office,

head of district education council, subdistrict MBS

team leader, and a secretary facilitated by the

district. In NTT-PEP, the trainers were international

MBS advisors, local MBS advisors, and gender

advisors. Participants were members of the school

committee, parents, and community leaders. The

methods used in the training were lectures, group

discussions (including focus group discussions),

simulations, modelling, participatory approaches.

At the school cluster level, BEP gave special

attention. The goals were to increase the knowledge

of school rehabilitation teams in planning and

managing school rehabilitation grants and providing

technical assistance to field coordinators in directing

physical work. The contents were: eligible school

selection criteria, regulations for implementing

school rehabilitation through school-community

partnerships, job descriptions of the school

rehabilitation team and field consultants, community

roles in rehabilitation and maintenance, the trainers

were national consultants (financial management,

procurement, construction). They trained Provincial

Project staff and District Project officers and related

units through participatory lectures and discussions.

For the school level, CLCC had a special

capacity building. The goal was to provide technical

assistance (extended training) to teachers in schools.

Provincial and district trainers trained teachers

during school hours through monitoring of teaching

practice, discussing and providing feedback. It was

organized by the Office of the District Office and the

Sub-District Branch Office.

4 METHODS

The purpose of this study was evaluation of

community participation in basic education schools.

The main question was how well the degree of

performance each participation aspects of the

community in schools that have experienced

educational innovation programs in terms of

education and project level.

Relevant tools needed for further study were

guideline for focus group discussion and

questionnaire. These were used in order to get the

data from the field.

Selected samples from 8 districts and 7 cities

from seven provinces based on four criteria. First,

the availability of programs that offered good

practices in the nine programs discussed in previous

sections, in the province and district respectively.

Second, the number of projects offered in certain

provinces, districts and subdistricts. Third, the

availability of schools where good practices, from

the nine programs were implemented. And fourth,

the preparedness of provinces, districts, subdistricts,

and schools to be visited.

The provinces that were decided to visit were

Central Java (Magelang City and Pekalongan

Regency), West Java (Sukabumi, Bekasi, and Kota

Bogor), West Nusa Tenggara (Central Lombok and

Mataram), Nusa Tenggara Timur (Ende Regency

and Kupang City), South Sulawesi (Bantaeng

Regency and Makassar City), South Kalimantan

(Barito Kuala District and Banjarmasin City), North

Sumatra (Deli Serdang District and Medan City).

From each district/city, 10-20 elementary schools

and about 10 junior secondary schools were picked

up.

Samples for questionnaires in 364 schools (264

elementary and 116 junior secondary schools)

consisted of 2415 teachers (1435 primary and 980

junior secondary teachers), 1785 parents/

community members (1289 in primary and 496 in

junior secondary). In each district, 80 people

(teachers and parents/community members) were

included in the Focus Group Discussion.

The quantitative data obtained were analyzed

descriptively and presented in graphs and supported

by qualitative data. Basically, comparisons between

projects were very useful in answering research

questions by taking into account the prominent good

practices of related projects.

ANCOSH 2018 - Annual Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities

172

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The five components of community participation,

obtained through focus group discussions (FGDs)

were: the form and intensity of community

involvement, community needs, community

satisfaction, communication systems, and

community-school partnerships. These five

components were accepted as a reflection of the

involvement under investigation (Barnett and

O'Mahony, 2007; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 1995;

Sylva and Siraj-Blatchford, 1995). Each component

was elaborated into questionnaire form to obtain

data for the following analysis.

The first component was regarding the activities

and their intensities. The community participation in

various school activities was not apart from school

initiatives to invite them in various meetings. It was

important to the principals to accommodate teacher

and community participation in wide variety of

forms including questions, information, suggestions,

and objections. The high level of accommodation

by principal in primary level came from MBE, NTT-

PEP, and BEP. In addition, community or parents as

well as school committee were involved in

formulating school policies and plan.

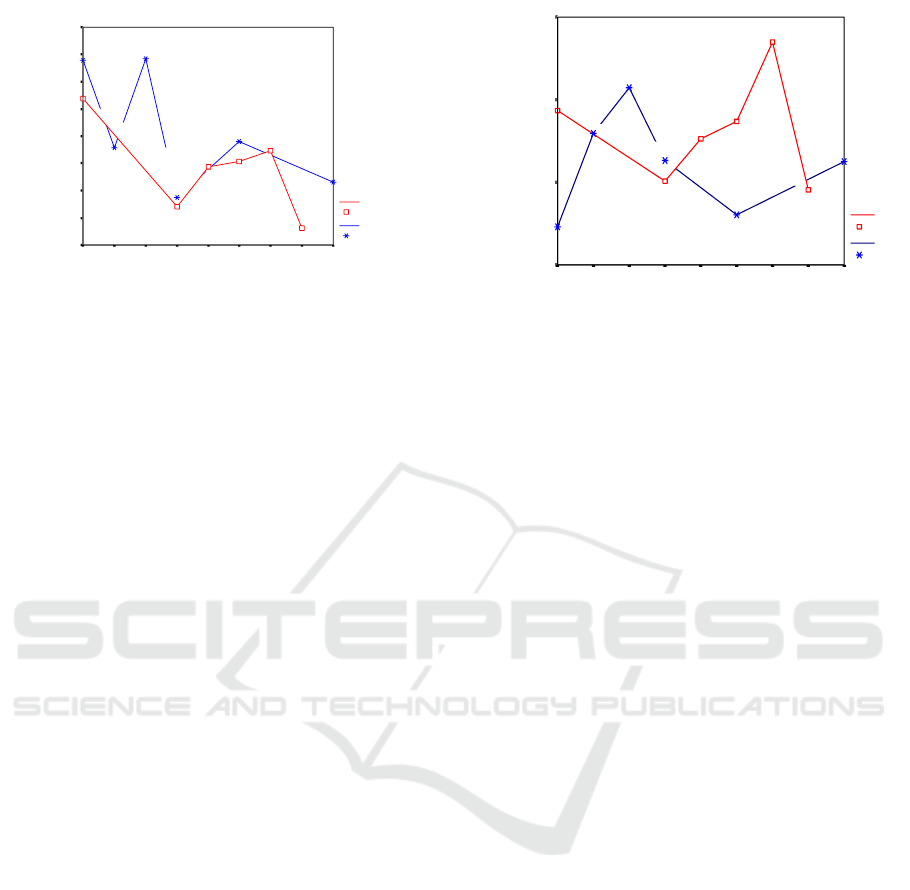

Potential good practices of community

participation, as in Figure 1, were viewed based on

education level, i.e. primary and junior secondary

schools. In primary level, the prominent potential

good practices for this sub-component were in NTT-

PEP, MBE and CLCC; while in junior secondary

level were in DBEP, MBE and REDIP-G.

The evidences of such good practices based on

local characteristics in primary level prominently

emerged at District of Bekasi, Bantaeng and Ende;

whereas in junior secondary level these emerged in

District of Ende, Barito Kuala and Bantaeng. There

was significant difference of community

participation by education level in several

district/kotas as shown in Kota Kupang, District of

Bekasi, and Kota Banjarmasin. It seemed that some

projects may have influenced the others. For

instance, District of Bekasi, which junior

secondaries are developing good practices under

REDIP-G, also has the same potential good practices

in their primary level developed under BEP. Hence

community participation succeeded in different

places and programs as part of education in terms of

caring children and the degree of fulfilling their

needs (Epstein, 1995; Osterman, 2000; Henderson

and Map. 2002).

Proyek/program

CTL

SEQIP

NTT PEP

BEP

CLCC

DBEP

REDIP G

REDIP JICA

MBE

Keterlibatan masy

2.7

2.6

2.5

2.4

2.3

SEKOLAH

SD

SLP

Figure 1: Programs by education level.

The second component was on community

needs. Potential good practices of community needs

emerged with the indicators including community

aspiration of education, collaboration level among

parents to support education programs at school, and

the communities knew their children performance at

the school without asking to the school. The

following Figure 2 showed the community response

to their aspiration in education based on education

level.

The figure illustrated that community aspiration

generally emerged in each project with varied

intensities. Based on education level, the response to

community needs in junior secondary level was

higher than those in primary. For primary level,

potential good practices in accommodating

community needs emerged in MBE, NTT-PEP, and

BEP; meanwhile in junior secondary level such

potential good practices emerge in REDIP-G, MBE

and BEP.

In view of local characteristics (district/kota)

potential good practices for the component of

community needs seemed to be varied among

regions in line with the existence of project in each

district/kota. As shown in Kota Mataram, Kota

Bogor, Barito Kuala, and District of Deli Serdang,

accommodation to community needs in primary

level and junior secondary level was significantly

different to each other; while in other districts/kotas

were relatively the same. The community needs

were fulfilled as affected by the programs which

start from the upper level of schools related to the

policies (Henderson and Map, 2002; Osterman,

2000; JICA, 2013).

Figure 3. Community Satisfaction

The Evaluation of Community Participation in Basic Education Management

173

Proyek/program

CTL

SEQIP

NTT PEP

BEP

CLCC

DBEP

REDIP G

REDIP JICA

MBE

Mean NO8ABC

3.7

3.6

3.5

3.4

3.3

3.2

3.1

3.0

2.9

SEKOLAH

SD

SLP

Figure 2: Community Needs.

The third component was related to the

community satisfaction. The development and

existence of the school would highly depend on the

trust and satisfaction of consumers (community).

The community satisfaction in school could be

identified in several aspects, including satisfaction in

school performance covering student performance

and preparation of student to face occupation

demand.

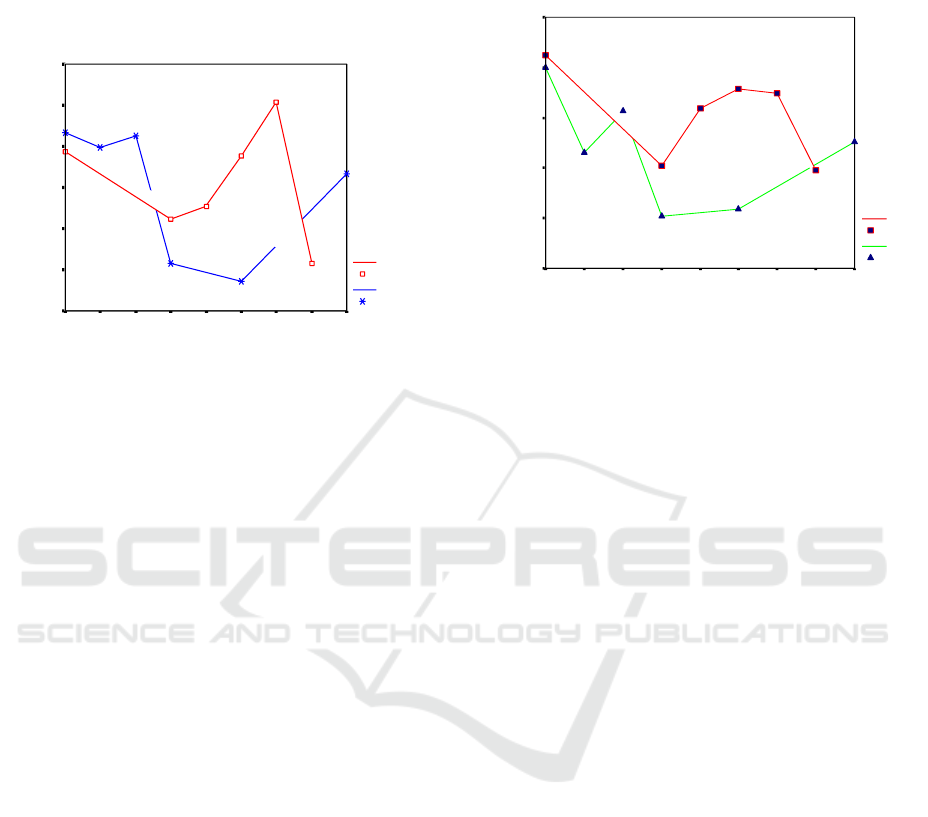

In view of education level, Figure 3, the

prominent good practices of community satisfaction

in primary level were shown in NTT-PEP, MBE and

BEP. Under NTT-PEP regular reporting of student

performance by the school had been the aspect

highly needed by the community dealing with the

children performance. In junior secondary level, the

prominent potential good practices for sub-

component of community satisfaction appeared in

REDIP-G, REDIP-JICA, and BEP. The schools

under REDIP-G the community satisfaction was

particularly related to the preparation of student to

face occupation challenge in the future. For instance,

several junior secondary schools developed

computer laboratory and internet network with

support from LG Electronics and in cooperation with

PT Telkom.

The community satisfaction in view of condition

of district/kota seemed to be consistent in both

education levels, primary and junior secondary, in

the same region. The most potential good practices

of this sub-component in primary level in Kota

Kupang were the contribution of CLCC and SEQIP;

on the other hand, for junior secondary level were

shown in REDIP-G, REDIP-JICA, and CTL. The

results revealed that for being satisfied, there were

no need to elaborate it in detail since it was

consequence of good performance (Dutta-Beergman,

2005; Zürcher, 2013; Panduprodjo, 2015).

Figure 3: Community satisfaction.

The fourth component was on communication

systems. Emerging potential good practices of the

communication systems were the efforts to initiate

the relationship within the school and stakeholders

effective and accurate. Of course, the systems itself

opened to be assessed by principal, teacher, staff,

and stakeholders, and to enable adequate resolution

of school problems.

Figure 4 clearly showed that between the

primary and junior secondary, the potential good

practices of system communication in primary level

were shown in NTT-PEP, MBE, and BEP.

Particularly the systems under NTT-PEP was

developed through radio, which was a cooperation

between NTT-PEP and local radio stations;

however, for junior secondary level such potential

emerged in MBE, REDIP-G, and REDIP-JICA. For

MBE, the communication system was developed

through various media such as MBE Voice, website,

and other communication media.

In view of local characteristics, the potential

good practices on communication sub-component in

primary level was better in average compared with

those in junior secondary level. This because of

better relationship between parents and schools

happened. Even CLCC had developed an association

of parents for one classroom, which is able to act as

the bridge between student and parent needs, even,

in fact, the parents sometimes act as the teaching

learning resources. In view of local characteristics,

most potential good practices for the sub-component

of communication system in primary level came

from District of Bekasi, District of Deli Serdang,

and District of Pekalongan; while in junior

secondary level the most potential good practices

emerge in District of Ende, District of Bantaeng, and

Kota Bogor/District of Barito Kuala. Building the

system of communication not only requires the

participation of all people inside and outside the

Proyek/program

CTL

SEQIP

NTT PEP

BEP

CLCC

DBEP

REDIP G

REDIP JICA

MBE

Mean NO2

3.3

3.2

3.1

3.0

SEKOLAH

SD

SLP

ANCOSH 2018 - Annual Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities

174

Proyek/program

CTL

SEQIP

NTT PEP

BEP

CLCC

DBEP

REDIP G

REDIP JICA

MBE

Mean NO6

3.4

3.3

3.2

3.1

3.0

2.9

2.8

SEKOLAH

SD

SLP

school but also adjusts the programs to the local

conditions in different cultural background (Fitriah

et al., 2013; Cuellar and Theriot, 2017; Berger,

1991).

Figure 4: Communication system.

The last component pertaining the school-

community partnership was described. The potential

good practices of partnership were emerging in the

projects include community aspiration in education,

level of parental cooperation to support education

programs in school level, and parent’s assistance to

the children doing homework.

The illustration in Figure 5 expressed the

potential good practices of partnership sub-

component in primary level was better than those in

junior secondary level. For primary level, the most

potential good practices of this sub-component

emerge were shown in MBE, BEP, and NTT-PEP,

while in junior secondary level the contribution of

MBE, REDIP-G, and REDIP-JICA was significant.

Local characteristics (district/kota) did not

always appear in line with education level as shown

in Figure 5. It was found that in District of Kupang

and Bekasi, the potential good practices of

partnership in primary level was better than those in

junior secondary level, while in District of

Banjarmasin the potential good practices of this

component was better than those in primary level.

The District that had equal prominent good practices

of this sub-component in both primary and junior

secondary levels was District of Bantaeng. The

significant gap of potential good practices between

primary and junior secondary levels within one

region was shown in Kota Kupang, District of

Bekasi, and Kota Banjarmasin. The genuine and

healthy participation is constructed when the

partnership exists (Brian and Griffin, 2010; Sanders,

2001; Chrispeels, 1996). Those conspicuous

programs had proved how to take care of partnership

in order to achieve such kind of participation.

Proyek/program

CTL

SEQIP

NTT PEP

BEP

CLCC

DBEP

REDIP G

REDIP JICA

MBE

Mean NO4

3.3

3.2

3.1

3.0

2.9

2.8

SEKOLAH

SD

SLP

Figure 5: Partnership.

6 CONCLUSIONS

All programs revealed that levels of education

interwoven community participation with varying

intensity. Although having a large variety in project

designs the involvement of community still appeared

as part of the overall development of education. The

strengths of NTT-PEP included aspects of

community involvement in planning and

implementation, community satisfaction, and

communication systems with communities; the MBE

on the partnership aspect; the REDIP-G on

community needs and community satisfaction; the

REDIP-JICA's strengths on communication system

and partnership; and the DBEP on community

involvement in school planning. The capacity that

made the success of implementation at

district/municipality level and schools depending on

the conditions of both providers’ and education

stakeholders’ commitment, the availability of

various supporting regulations, and the availability

of adequate human resources.

REFERENCES

ADB, 2001. Completion Report on the Junior Secondary

Education Project. (Loan 1194-INO). ADB PCR:

INO 24332. May.

ADB, 2004. Second Junior Secondary Education Project.

Loan 1573/1574-INO: Main Project Completion

Report. May.

The Evaluation of Community Participation in Basic Education Management

175

Anam, S., 2006. Sekolah Dasar: Pergulatan Mengejar

Ketertinggalan, Wajatri. Solo.

Barnett, B. G., O’Mahony, G. R., 2007. Developing a

Culture of Reflection: implications for school

improvement. Reflective Practice, 7(4), 499-523.

Bandur, A., 2011. Challenges in Globalising Public

Education Reform: Research-Based Evidence from

Flores Primary Schools, Global Journal of Human

Social Science Research, 11(3).

Bandur, A., 2012. Decentralization and School-Based

Management in Indonesia. Asia Pacific Journal of

Educational Development, 6(1), 33-47.

Berger, E. H., 1991. Parent Involvement: Yesterday and

Today, Elementary School Journal, 91(3), 209-219.

Bergmann, H., Whewell, E., 2001. Report of SEQIP

Project Progress Review 2001. 21-31 August.

Brian, J., Griffin, D., 2010. A multidimensional study of

school-family-community partnership involvement:

School, school counselor, and training factors,

Professional School Counseling, 14(1), 75-86.

Bundu, P., 2009. Partisipasi Masyarakat dalam Pendidikan

Dasar dan Menengah, Journal Pendidikan dan

Kebudayaan, 15(3), 451-468.

Chrispeels, J., 1996. Effective schools and

home‐school‐community partnership roles: A

framework for parent involvement, School

Effectiveness and School Improvement, 7(4), 297-323

Cohen-Vogel, L., Goldring, E. Claire Smrekar, E. C.,

2010. The Influence of Local Conditions on Social

Service Partnerships, Parent Involvement, and

Community Engagement in Neighborhood Schools,

American Journal of Education, 117 (1) , 51 – 78.

Cuellar, M. J., Theriot, M. T., 2017. Investigating the

Effects of Commonly Implemented School Safety

Strategies on School Social Work Practitioners in the

United States, Journal of the Society for Social Work

and Research, 8(4), 511–538.

Dreikurs, R. C. M., 1970. Parents and Teachers: friends or

enemies? Education, 91(2), 147-154.

Dutta-Beergman, M. J., 2005. Access to the Internet in the

Context of Community Participation and Community

Statisfaction. New Media and Society, 7(1), 89-109.

Epstein, J. L., 1995. School/Family/Community

Partnerships. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701.

Epstein, J. L., 2009. School, Family, and Community

Partnership: caring for the children we share. In

School, Family, and Community Partnership: Your

Handbook for Action (pp 1-56). Edited by J.L.

Epstein Et Al. Corwin Press – Sage Company.

Thousand Oaks, CA

Firman, H., Tola, B., 2008. The future of schooling in

Indonesia, Journal of International Cooperation in

Education, 11(1), 71-84.

Fitriah, A., Sumintono, B., Subekti, N.B., Hassan, Z.,

2013. A Different Result of Community Participation

in Education: an Indonesian case study of parental

participation in public primary schools, Asia Pacific

Education Review, 13(4), 483-493.

Henderson, A. T., Mapp, K. L., 2002. A New Wave of

Evidence: the impact of school, family, and

community connections on student achievement –

annual synthesis 2002. National Center for Family

and Community Connections with Schools – SEDK.

Austin, TX.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Bassler, O. C., Burow, R., 1995.

Parents’ Students” Homework: strategies and

practices, The Elementary School Journal, 95(5),

435-450.

JICA, 2013. Program for Enhancing Quality of Junior

Secondary Education. (Downloaded from

https://www/JICA.go.jp/project/English/Indonesia/08

00042/index.html, accessed on April 11, 2018).

Ministry of Education and Culture, 2013. Overview of the

Education Sector in Indonesia: Achievement and

Challenges. Jakarta.

Muljoatmodjo, S., 2004. Task1 Most Critical and

important capacity gaps in basic education. Progres

Report 1 for UNICEF. Jakarta, June. (Unpublished).

Osterman, K. F., 2000. Students’ Need for Belonging in

the School Community, Review of Educational

Research, 70(3), 323-367.

Panduprodjo, P., 2015. SEQIP. Kapan lagi ada Program

Sejenis. (Downloaded from

https://www.kompasiana.com/mintadi/seqip-kapan-

lagi-ada-program-

sejenis_5528096df17e61a7068b4591, accessed on

April 10, 2018).

RTI-USAID, 2004. Managing Basic Education:

developing local government capacity (an

introduction to the program). Bulletin. May.

Sanders, M. G., 2001. The Role of "Community" in

Comprehensive School, Family, and Community

Partnership Programs, The Elementary School

Journal, 102 (1), 19 – 34.

Sunarsih, A., Sukarmin, and Sunarno, W., 2017. The

impact of natural science contextual teaching through

project method to students’ achievement in MTsN

Miri Sragen, International Journal of Science and

Applied Science: Conference Series, 2(1), 45-50.

Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., 1995. Bridging the Gap

Between Home and Schol: improving achievement in

primary schools. Unesco. Paris.

Tunison, S., 2013. The Wicehtowak Partnership:

Improving Student Learning by Formalizing the

Family-Community-School Partnership, American

Journal of Education, 119 (4), 565 – 590.

USAID-Prioritas, 2016. Managing Basic Education

(MBE). Downloaded from

http://www.prioritaspendidikan.org/en/pages/view/re

ad/decentralized-basic-education, accessed on April

10, 2017).

World Bank, 2000. Implementation Completion Report on

Indonesia Primary Education Quality Improvement

Project. Loan 3448-IND. Report No. 20435-IND. 20

April.

Zürcher, D., 2013. Ex-post Evaluation of SEQIP in

Indonesia (2013). On

http://www.kek.ch/en/kunden/mandate/145 (retrieved

on 10 April 2018).

ANCOSH 2018 - Annual Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities

176