Generalized Primary Anetoderma: A Rare Case

Dina Fatmasari, Reti Hindritiani, Kartika Ruchiatan, R. M. Rendy Ariezal E.

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran - Dr. Hasan Sadikin Hospital,

Bandung 40161 Indonesia

Keywords: Anetoderma, autoimmunity, generalized, primary

Abstract: Anetoderma is a rare elastolytic disorder characterized by localized areas of slacks skins, that are reflection

of a marked reduction or absence of dermal elastic fibers, that can appear as round or oval atrophic lesions,

and wrinkling or sac-like protrutions. The predilection of lesions are on the trunk, thigh, and upper arms,

and rarely occur on generalized distribution,. Primary anetoderma occur when there is no underlying

cutaneous diseases, but could be associated with autoimmune diseases such as antiphospholipid syndrome

and autoimmune connective tissue diseases. The aim of this report was to present a rare case of generalized

primary anetoderma. A 19-year-old female had asymptomatic, multiple, small, circumscribed, round and

oval atrophic lesions and sac-like protrution on almost all part of the body since 6 years ago without

preceding cutaneous diseases. Histopathological examination with Verhoeff-Van Gieson elastin stain

revealed fragmented and decreased of elastic fibers from superficial dermis until mid-dermis, and loss of

elastic fibers in mid-dermis that confirmed the diagnosis of anetoderma. Laboratory test for autoimmune

connective tissue diseases and antipospholipid syndrome were negative. Anetoderma is a benign disease,

but can remain active for many years resulting in considerable aesthetic deformity, moreover in generalized

distribution. Although no autoimmunologic abnormalities, long term follow-up is mandatory as an early

warning signs of future symptoms of autoimmunity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Anetoderma is an uncommon disease characterized

by focal loss of elastic tissue, resulting well-

circumscribed areas of atrophic skin or sac-like

protrutions (Bilen et al., 2003). The pathogenesis of

anetoderma is still unknown (Staiger et al., 2008;

Maari and Powell, 2012). Due to its low frequency,

only isolated reports and series with few cases have

been published (Staiger et al., 2008). The

characteristic of lesions are circumscribed areas of

slack skin with the impression of loss dermal elastic

tissue forming round or oval atrophic lesions, and

wrinkling or sac-like protrutions (Maari and Powell,

2012). The lesions commonly occur in young adults

with the usual locations on the trunk, thighs, and

upper arms, less commonly on the neck and face and

rarely elsewhere (Burrows et al., 2010). According

to author knowledge, there are only two cases of

generalized anetoderma have been reported (Emer et

al., 2013; Inamadar et el., 2003). Anetoderma

lesions classified into primary and secondary types

(Emer et al., 2013). Primary anetoderma develops in

clinically normal skin and have been related to a

variety of pathologies, mainly autoimmune diseases

(Staiger et al., 2008). Primary anetoderma may be as

a cutaneous sign of autoimmunity, whereas

autoimmune diseases may develop later after the

onset of anetoderma (Al Buainain and Allam, 2009).

Secondary anetoderma arises on previous skin

diseases, although not always in relation to the

lesions, and could be associated with syphilis and

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Bilen et al.,

2003). There is no effective treatment for

anetoderma (Maari and Powell, 2012), the new

lesions often continue to develop for many years as

the older lesions fail to resolve (Maari and Powell,

2012). The aim of this report was to present a rare

case of generalized primary anetoderma.

2 CASE

A 19-year-old female was noticed to have had

asymptomatic, multiple, small, circumscribed, round

and oval atrophic lesions and sac-like protrution on

446

Fatmasari, D., Hindritiani, R., Ruchiatan, K. and Ariezal E., R.

Generalized Primary Anetoderma: A Rare Case.

DOI: 10.5220/0008159404460450

In Proceedings of the 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology (RCD 2018), pages 446-450

ISBN: 978-989-758-494-7

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

almost all part of the body. The lesions started on

elbows without history of skin lesion on the areas of

the lesions and spread to almost all part of the body

in 6 years duration. Skin lesions consisted of

scattered, well-circumscribed, round and oval, skin

color and white lesions, atrophic and some lesions

raised above the surrounding skin level (sac-like

protrutions). On palpation, a hernia orifice could be

fell under the finger, and the content of the hernia

sac could be pressed through this orifice, producing

the “button-hole sign”. Size of lesions are 0,5 until 2

centimeter in diameter with central protrusion, that

were distributed on almost all part of the body with

sparing in scalp, palms, and soles (figure 1). No

sensory changes associated with the lesions. She did

not have any history of medication consumption. No

family history with the same symptoms. Skin biopsy

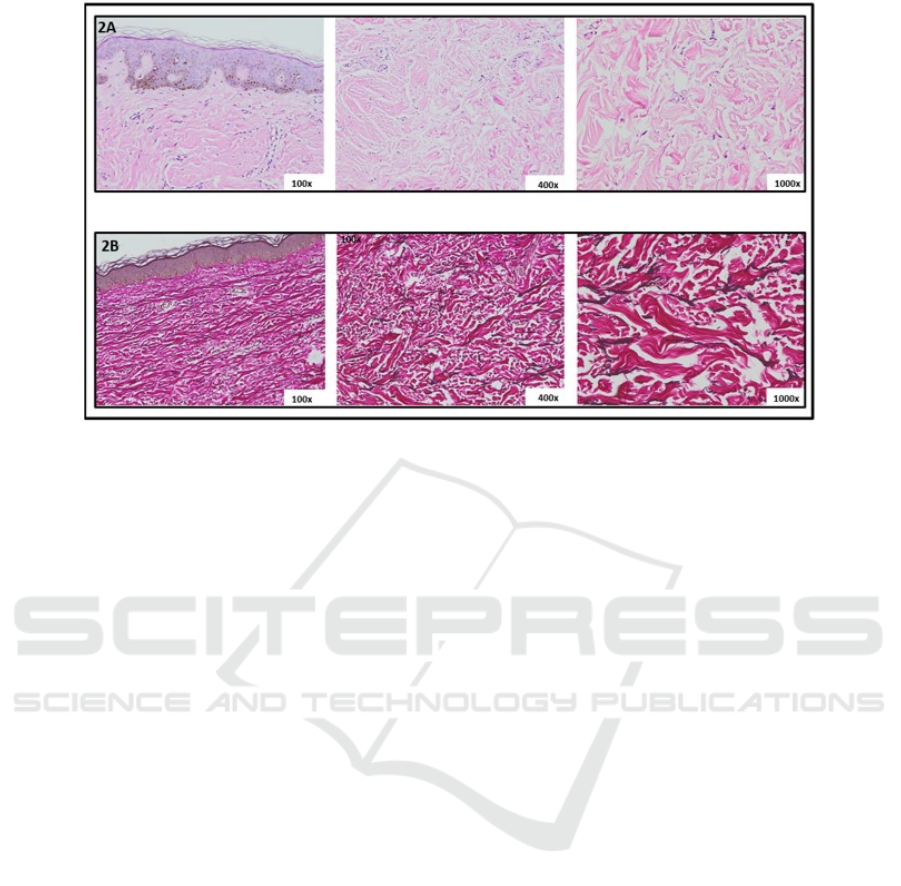

was taken from atrophic and protruding lesions for

histopathological examination and both revealed

perivascular and periadnexal lymphocyte

inflammatory cell infiltrate (figure 2A). Verhoeff-

Van Gieson elastin stain showed fragmented and

markedly decreased of elastic fibers in the

superficial dermis until mid-dermis and loss of

elastic fibers in mid-dermis (figure 2B) supported

the diagnosis of anetoderma. Direct

immunofluorescence (DIF) did not performed.

Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation

rate, and routine chemistry were normal. The patient

did not have any symptoms or show any signs of

antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and screening for

antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin IgG and

IgM) were negative. Bleeding time and clotting time

were within normal range. Antinuclear antibody

(ANA) and ANA profile were negative. Thyroid

panel test did not performed. Venereal disease

research laboratory (VDRL) test, Treponema

pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA), anti-

HIV were all non-reactive.

3 DISCUSSION

The term “anetoderma” is derived from anetos, the

Greek word for slack, and derma for skin (Maari and

Powell, 2012). This disease favors young adults

between 15 (Maari and Powell, 2012) and 40 years

(Aghaei et al., 2004). and occurs more frequently in

women than men (Maari and Powell, 2012; Aghaei

et al., 2004). The characteristic lesions of

anetoderma are flaccid circumscribed areas of slack

skin that are reflection of a marked reduction or

absence of dermal elastic fiber and can appear as

depressions, wrinkling or sac-like protrusions (Maari

and Powell, 2012). The lesions appear as

circumscribed round or oval areas of the skin with

atrophic aspect (Staiger et al., 2008) and protrude

from the skin and on palpation have less resistance

than the surrounding skin, producing the “button-

hole” sign. (James et al., 2016). The lesions can vary

in number from less than five (Burrows et al., 2010)

to hundreds, and they typically measure 0,5 (Aghaei

et al., 2004) -2 cm in diameter (Maari and Powell,

2012). The color varies from skin color, blue, white

(Maari and Powell, 2012); Burrows et al., 2010), and

grey (Burrows et al., 2010). The surface skin may be

slightly shiny, white, and crinkly. The patient may

be totally asymptomatic or refer pruritus on the

lesions (Staiger et al., 2008). In our case, the patient

is a 19 years-old female, presented with

asymptomatic, multiple, small, circumscribed, round

and oval atrophic lesions and sac-like protrution on

almost all part of the body. The lesions are 0,5 until

2 centimeter in diameter with central protrusion,

skin color and white, with some had slightly shiny

and crinkly surface.

The usual locations of anetoderma are the trunk,

especially on the shoulder, the upper arms, and thigh

(Maari and Powell, 2012; Burrows et al., 2010), less

commonly on the neck and face and rarely

elsewhere. The scalp, palms, and soles are usually

spared (Burrows et al., 2010). There were only few

reported cases of anetoderma with generalized

distribution (Emer et al., 2013; Inamadar et al.,

2003). Emer et al. (2013) reported one case of

generalized anetoderma in a patients with secondary

syphilis after being treated with intravenous

penicillin. Inamadar et al. (2003) reported a case of

generalized secondary anetoderma in a patient with

HIV infection, pulmonary tuberculosis and

lepromatous leprosy. The new lesions often continue

to form for many years as the older lesions fail to

resolve (Maari and Powell, 2012. The distribution of

the lesions in this report are generalized, affecting

almost all part of the body, and sparing on scalp,

palms, and soles. The lesions started on elbows

without history of skin lesion on the areas of the

lesions and spread to almost all part of the body in 6

years duration.

The pathogenesis of anetoderma is still unknown

(Staiger et al., 2008; Maari and Powell, 2012). The

loss of dermal elastin may reflect an impaired

turnover of elastin, caused by either increased

destruction or decreased synthesis of elastic fibers.

There are a number of proposed explanations for the

focal elastin destruction such as the release of

elastase from inflammatory cells, the release of

cytokines such as interleukin-6, an increased

Generalized Primary Anetoderma: A Rare Case

447

production of progelatinases A and B, and the

phagocytosis of elastic fibers by macrophages

(Maari and Powell, 2012).

The diagnosis of anetoderma is based on an

association of clinical features, and the

histopathological examination. In the routinely

stained sections, the collagen within the dermis of

affected skin appears normal. A perivascular

inflammatory infiltrate is present that lymphocytes

were the predominant cell type. There are usually

some residual abnormal irregular and fragmented

elastic fibers. Plasma cells and histiocytes with

occasional granuloma formation can be seen (Emer

et al., 2013). The predominant abnormality is a

focal, more or less complete loss of elastic tissue in

the papillary and/or mid-reticular dermis as revealed

by elastic tissue stain such as Verhoeff-Van Gieson

stain (Staiger et al., 2008; Maari and Powell, 2012).

Direct immunofluorescence sometimes shows linear

or granular deposits of immunoglobulins and

complement along the dermal-epidermal junction or

around the dermal blood vessels in affected skin.

However, these findings are not helpful

diagnostically (Maari and Powell, 2012). In this

patient, the histopathologic examination revealed

perivascular and periadnexal lymphocyte

inflammatory cell infiltrate. Elastic stain (Verhoeff-

Van Gieson) showed fragmented and markedly

decreased of elastic fibers in the superficial dermis

until mid-dermis and loss of elastic fibers in mid-

dermis and the diagnosis was consistent with

anetoderma. We did not perform direct

immunofluorescence (DIF) examination in this

patient.

Figure 1. Multiple, small, circumscribed, round/oval, skin color and white, atrophic lesions and sac-like protrutions on

almost all part the body with “button-hole sign” on palpation.

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

448

Figure 2. Histopathological examination. 2A. Hematoxilin-Eosin stain 2B. Verhoeff-Van Gieson elastin stain

Two forms of anetoderma are traditionally

distinguished, primary and secondary (Staiger et al.,

2008; Persechino et al., 2011). The lesions of

primary anetoderma occur in clinically normal skin

(Maari and Powell, 2012; Persechino et al., 2011)

although there could be an association with other

dermatological or systemic diseases or conditions,

without a well-established relationship (Persechino

et al., 2011). Some author classified primary

anetoderma into two major forms, Jadassohn-

Pellizzari type which is preceded with inflammatory

lesions, and Schweninger-Buzzi type without

preceding inflammatory lesions. This clinical

classification is primarily of historical interest, since

the two types of lesions can coexist in the same

patient and their histopathology is often the same

and not related to prognosis (Maari and Powell,

2012). In the secondary anetoderma the lesions can

occurs on the same site as another skin lesions

(Persechino et al., 2011), including acne, insect

bites, varicella, syphilis, leprosy, tuberculosis,

granuloma annulare, and urticarial pigmentosa, but

no always in relation to the lesions (Emer et al.,

2013). The diagnosis of primary anetoderma can be

established only by excluding the presence of any of

the diseases known to be associated with secondary

atrophy (Burrows et al., 2010). We diagnosed this

patient as primary anetoderma because the patient

did not noticed any signs of inflammatory lesions or

skin diseases preceded the lesions. We performed

laboratory test for syphilis and HIV infection which

could be the etiology of secondary anetoderma, and

the results were all non-reactive.

Primary anetoderma has been related to multiple

diseases. For some time, its association with

autoimmune pathologies has been highlighted,

mainly systemic lupus erythematosus and

antiphospholipid syndrome (Staiger et al., 2008).

There are some evidence to consider primary

anetoderma as a cutaneous sign of positive

antiphospholipid antibodies with or without

fulfilling the criteria antiphospholipid antibodies

syndrome (Al Buainain and Allam, 2009). Several

studies have subsequently linked anetoderma with

concurrent Grave’s disease (autoimmune

thyroiditis), autoimmune hemolysis, systemic

sclerosis, and alopecia areata (Emer et al., 2013).

Xia et al. (2016) reported a case of anetoderma in a

patient with SLE, who around the time of

anetoderma presentation was negative for

antiphospholipid antibody but who later went on to

develop antiphospholipid antibody (IgM

anticardiolipin). They suggest that anetoderma can

precede antiphospholipid antibody serologic

conversion and continued monitoring of

antiphospholipid serology regardless of initial

serology will be important. Bergman et al. (1990)

described a case of primary hypothyroidism that

developed 3 years after the onset of anetoderma.

From some literature suggested to think of primary

anetoderma as a cutaneous sign of autoimmunity and

patients should be examined and carefully tested for

autoimmune diseases, especially for

antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus erythematosus

and also thyroid antibodies. Patients should also be

followed up because associated autoimmune

Generalized Primary Anetoderma: A Rare Case

449

diseases may develop later in the course of the

disease (Al Buainain and Allam, 2009). Evaluation

for the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies

should be performed before patients with idiopathic

anetoderma are labeled as having true primary

anetoderma (Maari and Powell, 2012). Laboratory

examinations for autoimmune connective tissue

diseases and antipospholipid syndrome in this

patient were negative. There were no sign and

symptoms of autoimmunity diseases confirmed the

diagnosis of idiopathic primary anetoderma. In this

patient, we plan long-term follow-up to monitor if

there will develop any signs and laboratory

abnormalities suggest to autoimmunity diseases.

Anetoderma is a benign condition (Persechino et

al., 2011), and the disease can remain active for

many years resulting in considerable aesthetic

deformity (Zaki et al., 1994). Venencie et al. (1984)

studied 16 patients and found that no treatment was

beneficial once the depressed lesions had developed.

Various therapeutic modalities have been tried, but

have not resulted in improvement of existing

atrophic lesions, these include intralesional

injections of triamcinolone and systemic

administration of aspirin, dapsone phenytoin,

penicillin G, vitamin E, and inositol niacinate.

Surgical excision of limited lesions may be helpful,

with consideration the possibility of scars formation

(Maari and Powell, 2012).

4 CONCLUSION

Anetoderma is rarely occur in generalized

distribution. In each case of anetoderma, it is

important to determine the case of primary or

secondary, and patients should be examined,

carefully tested, and followed up for autoimmune

diseases. This is a benign condition, no effective

treatment, and the new lesions often continue to

form as the older lesions fail to resolve results in

aesthetic deformity.

REFERENCES

Aghaei S, Sodaifi M, Aslani FS, Mazharinia N. An

unusual presentation of anetoderma: a case report.

BMC Dermatol. 2004;4(1):9.

Al Buainain H, Allam M. Anetoderma: Is It a Sign of

Autoimmunity? Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1(1):100-4.

Bergman R, Friedman‐Birnbaum R, Hazaz B, Cohen E,

Munichor M, Lichtig C. An immunofluorescence

study of primary anetoderma. Clin Exp Dermatol.

1990;15(2):124-30.

Bilen N, Bayramgürler D, Şikar A, Ercin C, Yilmaz A.

Anetoderma associated with antiphospholipid

syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus.

2003;12(9):714-6.

Burrows NP, Lovell CR. Anetoderma. In: Burns T,

Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's

textbook of dermatology.8

th

ed. Oxford: Willey-

Blackwell; 2010. h. 45.17-45.18.

Emer J, Roberts D, Sidhu H, Phelps R, Goodheart H.

Generalized Anetoderma after intravenous penicillin

therapy for secondary syphilis in an HIV Patient. The

Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology.

2013;6(8):23.

Inamadar AC, Palit A, Athanikar S, Sampagavi V,

Deshmukh N. Generalized anetoderma in a patient

with HIV and dual mycobacterial infection. Lepr Rev.

2003;74(3):275-8.

James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, Isaac MN.

Anetoderma (macular atrophy). In: James WD, Berger

TG, Elston DM, Isaac MN, editors. Andrews' diseases

of the skin clinical dermatology.12

th

ed. Philadelphia:

Elsevier-Book Aid International; 2016. p. 507.

Maari C, Powell J. Atrophies of connective tissue. In:

Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, Editors.

Dermatology. 3

rd

ed. New York: Elsevier Saunders;

2012. p. 1631-40.

Maari C, Powell J. Antoderma and other atrophic

disorders of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI,

Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffel DJ, Wolff K, editors.

Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine.8

th

ed.

New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. p. 718-24.

Persechino S, Caperchi C, Cortesi G, Persechino F, Raffa

S, Pucci E, et al. Anetoderma: evidence of the

relationship with autoimmune disease and a possible

role of macrophages in the etiopathogenesis. Int J

Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24(4):1075-7.

Staiger H, Saposnik M, Spiner RE, Schroh RG, Corbella

MC, Hassan ML. Primary anetoderma and

antiphospholipid antibodies. Dermatología Argentina.

2008;14(SE):2008; 14 (5): 372-378.

Venencie PY, Winkelmann R, Moore BA. Anetoderma:

clinical findings, associations, and long-term follow-

up evaluations. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120(8):1032-9

Xia FD, Hoang MP, Smith GP. Anetoderma before

development of antiphospholipid antibodies: delayed

development and monitoring of antiphospholipid

antibodies in an SLE patient presenting with

anetoderma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;23(3).

Zaki I, Scerri L, Nelson H. Primary anetoderma:

phagocytosis of elastic fibres by macrophages. Clin

Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(5):388-90.

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

450