Case Report: A Case of Full Expressivity Piebaldism

Itrida Hadianti

1

, Prasta Bayu Putra

1

, Sekar Sari Arum Palupi

1

, Hanggoro Tri Rinonce

2

, Irianiwati

2

,

Hardyanto Soebono

1

, Sunardi Radiono

1

1

Department of Dermatology & Venereology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada / Dr. Sardjito General

Hospital, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2

Departement of Anatomical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada / Dr. Sardjito General Hospital,

Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: piebaldism, full expresivity, new mutant.

Abstract: Piebaldism is a rare inherited disease with a specific clinical manifestation. Here with, we reported a case

of piebaldism in a 17-year-old boy with the feature of a severe phenotype (full expressivity). White

forelock, poliosis, and depigmented patch observed on midline forehead and neck along with ventral and

lateral trunk, mid-arms, thighs, knees, and the lower leg area were found. Hyperpigmented macule between

depigmented lesions were found in all the lesions. The patient was a new mutant since his both parents were

normal. The diagnosis was established based on clinical appearance, histopathological examination, and

immunohistochemistry staining with S100, HMB45, and Fontana-Masson.

1 INTRODUCTION

Piebaldism (OMIM #172800) is an rare autosomal

dominantly inherited pigment anomaly characterized

by a congenital white forelock and leukoderma on

the frontal scalp, forehead, ventral trunk and

extremities (Oiso,2012). Its first descriptions date

back to early Egyptian, Greek and Roman writings

an it has been observed throughout history in

families with a distinctive, predictable congenital

white forelock (Spritz,1994). Although piebaldism is

a skin condition which occurs in limited and fixed

areas, it remains a social problem in patients so that

piebaldism therapy becomes a challenge to date

(Thomas,2004). The absence of melanocyte in

affected areas of the skin and hair is due to mutation

of the KIT protooncogenes, which affects the

differentiation and migration of melanoblast.

Piebaldism can also be caused by heterozygous

mutation in the gene encoding the zinc finger

transcription factor SNAI2 (Sanchez,2003)

(Taieb,2016).

The incidence of piebaldism is estimated to be

less than 1 among 20,000 people. Piebaldism

reported in all races with equally number between

women and men. The incidence of such cases is

estimated to be less than 1 among 20,000 people

(Agarwal,2012).

Medical record data of Dr. Sardjito

General Hospital showed that no case of piebaldism

were recorded for last 5 years and this is the first

case report of full expressivity piebaldism in

Indonesia.

Here with, we reported a case of piebaldism in a

17-year-old boy with the feature of a severe

phenotype. Piebaldism is a rare case, so this paper

may add some knowledge in giving a differential

diagnosis of skin disorders in the form of patch

depigmentation. Piebaldism become a challenge for

the dermatologist in diagnosis and therapy.

2 CASE

A 17-year-old boy from Purbalingga, Central Java,

came to the Dermatology and Venereology

Outpatient Clinic of Dr. Sardjito General Hospital

Yogyakarta, with the chief complaint of white

patches on his face and almost the entire body. He

had a white patches on the forehead and neck along

with white hair on the frontal part of the head.

Leukoderma appearance was also found in the chest,

abdomen, mid-arms, thighs, knees, and the lower leg

area. There were no complaints of visual

impairment, hearing loss, or expansion of the skin

Hadianti, I., Putra, P., Palupi, S., Rinonce, H., Irianiwati, ., Soebono, H. and Radiono, S.

Case Report: A Case of Full Expressivity Piebaldism.

DOI: 10.5220/0008160004730476

In Proceedings of the 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology (RCD 2018), pages 473-476

ISBN: 978-989-758-494-7

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

473

lesion areas of the patient. He never had any therapy

for the compaints before and no history of atopy and

drug allergy. Both of his parents were reported

without pigmentary disorders. The patient denied

any previous similar history of complaints, atopy,

drug allergy nor diabetes in the family members.

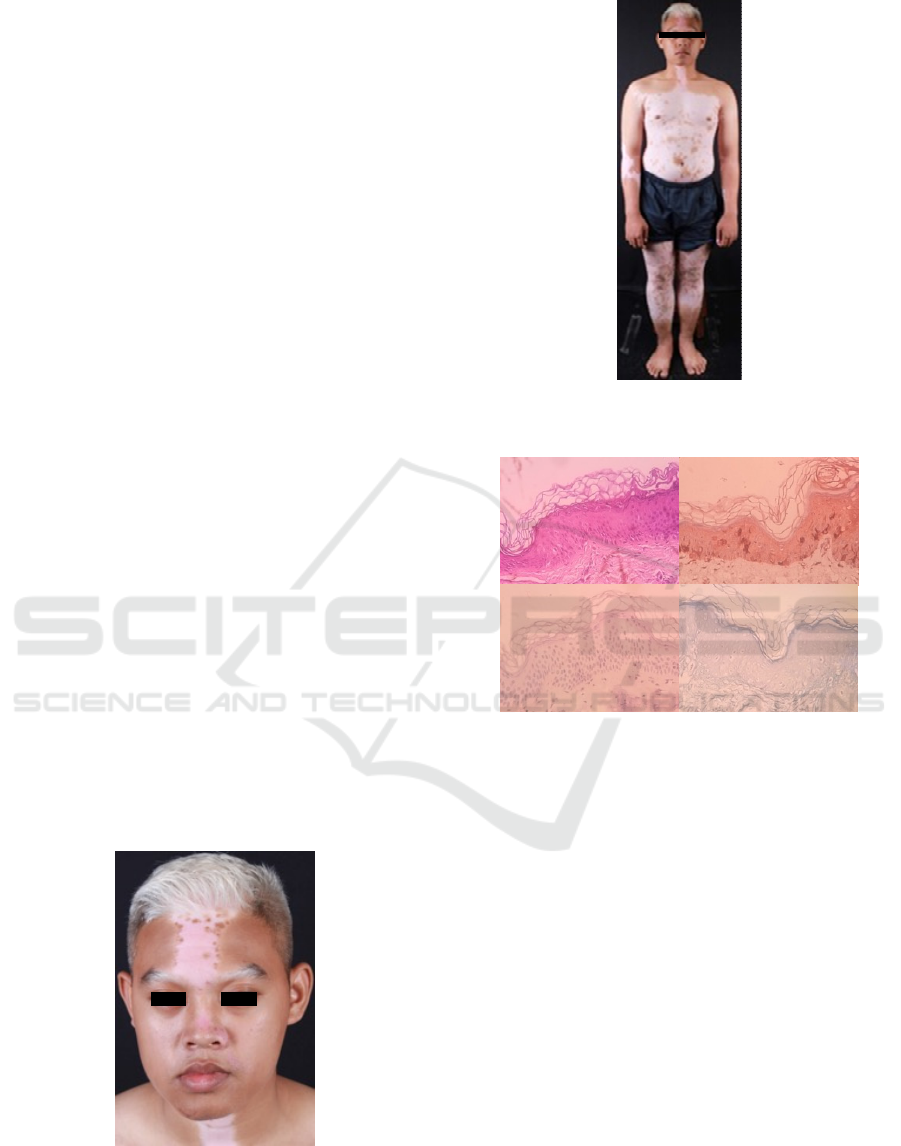

The general condition was good and dermatology

status showed a white forelock and poliosis on the

hair and medial eyebrow (Figure 1). There was

depigmented patch along the forehead until the nose

with hyperpigmented macule on the border area.

There were similar lesions on the neck, chest,

abdomen, the extensor sides of upper extremities,

thighs, knees, and up to the lower limbs in the form

of depigmented patches with edges and those of

which are hyperpigmented and normal pigmentation

macules (Figure 2). There was white hair on the

depigmented lesion. On the upper right and left back

showed ill-defined border of hypopigmented patches

and multiple hyperpigmented macules spread among

them. No skin lesions were found in the vertebral

area, hands, and feet. The differential diagnosis

presented for the patient was piebaldism, vitiligo and

Waardenburg syndrome.

Skin biopsy of depigmented area in the chest was

performed. Histopathologic examination revealed

basket weave type orthokeratosis, focal spongiosis,

and basal epidermal cell vacuolization. Melanocyte

and melanin were not found in the basal layer. There

was mild infiltration of inflammatory cells in the

perivascular and peri-appendicular area of the

dermis (Figure 3A). We also performed

immunohistochemistry staining with s100 and

Human Melanona Black 45 showed no positive

expression on melanocyte (Figure 3B&C). No

epidermal melanin were observe in Fontana-Masson

staining (Figure 3D).

Figure 1. White forelock and poliosis on the hair and

medial eyebrows.

Figure 2. Depigmented patch on neck, chest, abdomen,

and extremities in simetrically distribution.

Figure 3. Hematoxylin Eosin (A), S100 (B), HMB 45

(C), and Fontana-Masson (D) staining (x40)

The diagnosis of piebaldism was established by

clinical appearance, histopathological examination,

and immunohistochemistry staining with S100,

HMB45, and Fontana-Masson. The therapy was not

given to the patient due to family consideration of

the possibility for healing, the extent of the area of

the body involved, and also the transportation

problem.

3 DISCUSSION

Piebaldism is a pigmentation disorder that is

inherited by autosomal dominant means and rarely

occurs. It is mainly due to mutation in the KIT gene

(Xu,2016). KIT protooncogene encodes the cell-

surface receptor transmembrane tyrosine kinase for

the steel factor, an embryonic growth factor

(Thomas,2004). The formation of color of the skin,

A

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

474

hair, and eyes is determined by a multistep process:

(i) melanoblast migration to the skin of the embryo;

(ii) proliferation and survival of the melanocytes in

the basal layer of the epidermis; (iii) biogenesis of

the melanosomes in the melanocytes; (iv) production

of melanin granules in the melanosomes in the

melanocytes; (v) translocation of melanosomes from

the perinuclear region to peripheral region of the

melanocytes ; (vi) transfer of the melanosomes from

the melanocytes to the keratinocytes; and (vii)

translocation of the transferred melanin granules

from peripheral region to the supranuclear region of

the keratinocytes. Damage during the initial step

bring migration of the melanoblast in embryo and

induces most or all of the loss of the melanocytes in

the ventral skin and hair after birth. This is due to

melanoblasts originating from neural crest located in

the dorsal area and then migrating to the ventral area

(Oiso,2012).

The term piebald stems from the Latin word for

“magpie” and is used to describe animals whose

bodies are covered in blck and white patches

(Huang,2016). Piebaldism has a clinical picture of

white forelock and leucoderma in the scalp of the

frontal region, forehead, ventral trunk, and

extremities. Patients with piebaldism have hair and

skin depigmentation that is visible since birth, which

is relatively stable and persistent. White forelock

would often form a triangle shape and might result

as the only one manifestation in 80-90% of cases,

although the involvement can also be found on the

hair and skin in the area of the forehead that occurs

altogether (Oiso,2012). The description of poliosis is

based on the presence of localized patch on the

white hair. Poliosis can also affect the eyebrow and

eyelashes. There is a depigmented patch on the skin

with an irregular shape found on the face, trunk, and

extremities with symmetrical distribution. In

general, there are hyperpigmentation islands within

and at the border of the depigmentation area

(Thomas,2004). Patients with piebaldism may

develop café-au-lait spots (Oiso,2012). Pigmentary

anomalies in piebaldim are typically restricted to the

hair and skin. Some patients may get spontaneous

repigmentation, either partially or completely,

especially after injury (Thomas,2004).

Genetic analysis revealed that there was a

consistent relationship between genotype and

phenotype of piebaldism. Clinical manifestations

and phenotypic severity of piebaldism strongly

correlate with the site of mutations within the KIT

gene. Dominant negative missense mutation of the

intracellular tyrosine kinase domains appear to yield

the most severe phenotypes, while mutations of the

amino terminal extracellular ligand binding domain

result in haploinsufficiency and are associated with

the mildest forms of piebladism. Intermediate

phenotype are seen with mutation near the

transmembrane region (Thomas,2004). The severe

form shows a tipical white forelock on the frontal

scalp and relatively larger leukoderma on the chest,

abdomen, arms, and legs. The mild type may only

show relatively smaller leukoderma on the ventral

trunk and / or an extremity without a white forelock.

The moderate phenotype has an intermediate

appearance between the mild and severe form

(Oiso,2012)(Spritz,1994). In our patient, there was a

complaint of white patches on the body and white

hair on the front of the head that appeared from the

moment of birth. The stable depigmentation of the

patch depigmentation in the patient is suitable for

the description of piebaldism. This patient was

considered as severe phenotype and full expressivity

based on skin involving area and and location of the

lesion.

Melanocytes were not found or considered to be

diminished on the histopathologic examination taken

from the depigmentation patch. While in the

hyperpigmentation area, there is a normal number of

melanocytes found (Spritz,2009) (Thomas,2004)

(Treadwell,2015). Immunohistochemistry staining

with s100 is expressed un neural crest-derived cell

(melanocyte, Schwann cells, glial cells),

chondrocytes, fat cells, macrophages, Langerhans

cells, dendritic cells, some breast epithelial cells and

sweat glands. Another staining used in this case is

Human Melanoma Black 45 which expressed in

melanocyte that are synthesizing melanin. To

revealed melanin pigment in the basal layer that

usuallu not discernible in Hemathoxylin-Eosin-stain

section, requires a Fontana-Masson Stain for

confirmation (High,2012). We performed routine

histopathological examination and immuno-

histochemistry staining with S100, HMB45, and

Fontana-Masson thus proving that no melanocytes

nor melanin pigment in the basal layer.

Piebaldism therapy is still a challenge. Sunscreen

treatment is recommended to prevent burns and to

reduce carcinogenic potential

(Thomas,2004)(Milankov,2014). Facial makeup

application or pigmentation agents might be used to

disguise the area involved, even though it may only

be temporary. Various surgical techniques have been

performed, such as a combination of dermabrasion

and skin grafting with normal pigmentation to the

area of depigmentation, with or without

phototherapy, of which it may be of benefit to some

patients (Oiso,2012) (Thomas,2004)(Maderal,2017).

Case Report: A Case of Full Expressivity Piebaldism

475

In our patient, we planned a skin grafting for

treatment but the patient and family considerate to

not given the therapy regarding the healing

possibility, the extent of the body area involved,

including also the transportation problems.

4 CONCLUSION

A case of piebaldism in a 17-year-old boy with

full/complete phenotype expressivity was reported.

Routine histopathological examination with

hematoxylin-eosin staining cannot distinguish the

depiction of piebaldism, vitiligo, and Waardenburg

syndrome. The diagnosis of piebaldism in this

patients is based on anamnesis and physical

examination in accordance with the severe

phenotype, of which a typical white forelock

appearance was found on the scalp of the frontal

region and broad leukoderma on the chest, abdomen,

both arms, and legs. There are various alternative

therapies in the case of piebaldism, but the patient

rejected any therapy due to considerations of healing

possibility, the extent of the body area involved, and

also the patient's transportation problem.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, S., Ojha, A., 2012. Piebaldism: A Brief report

and review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J.

3, 144-147.

High, W.A., Tomasini, C.F., & Argenziano, G.Z. I., 2012.

Basic Principles of Dermatology. In Dermatology 3

rd

ed. London, Elsevier. 0:29-33.

Huang, A., & Glick, S.A., 2016. Piebaldism in history-

“The Zebra People”. JAMA Dermatol. 152:1261.

Maderal, A. D., & Kirsner, R. S., 2017. Use of Epidermal

Grafting for Treatment of Depigmented Skin in

Piebaldism. Dermatologic Surgery, 43(1), 159-160.

Milankov, O., Savić, R., & Radulović, A., 2014.

Piebaldism in a 3-month-old infant: Case

report. Medicinski pregled, 67(3-4), 109-110.

Oiso, N., Fukai, K., Kawada, A., & Suzuki, T., 2012.

Piebaldism. Journal of Dermatoogy, 39, 1-6

Sánchez‐Martín, M., Pérez‐Losada, J., Rodríguez‐García,

A., González‐Sánchez, B., Korf, B. R., Kuster, W., ...

& Sánchez‐García, I., 2003. Deletion of the SLUG

(SNAI2) gene results in human piebaldism. American

Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 122(2), pp. 125-

132.

Spritz, R. A., 1994. Molecular basis of human

piebaldism. Journal of investigative dermatology, 103,

137-140.

Taïeb,. A, Morice‐Picard, F., Ezzedine, K., 2016. Genetic

disorders of pigmentation. In Rook’s Texbook of

Dermatology 9

th

ed.; London, Wiley Blackwell, 70, 3.

Thomas, I., Kihiczak, G. G., Fox, M. D., Janniger, C. K.,

& Schwartz, R. A., 2004. Piebaldism: an

update. International journal of dermatology, 43(10),

pp. 716-719.

Treadwell, P. A., 2015. Systemic conditions in children

associated with pigmentary changes. Clinics in

dermatology, 33(3), pp. 362-367.

Xu, X. H., Ma, L., Weng, L., & Xing, H., 2016. A novel

mutation of KIT gene results in piebaldism in a

Chinese family. Journal of the European Academy of

Dermatology and Venereology, 30(2), 336-338.

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

476