Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to Reduce

Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD):

A Literature Review

Gst. Kade Adi Widyas Pranata

1

and A. A.Istri Wulan Krisnandari D.

1

1

ITEKES Bali (Institute of Technology and Health Bali), Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia

Keywords: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Anxiety, Children.

Abstract: Anxiety is the most common problem in children with ASD. Although CBT shown more positive response

in reducing anxiety than pharmacotherapy, the magnitude of effects varies ranging from small to robust

effects. Objective: This review was to summarize the magnitude of CBT’s effects in reducing anxiety in

children with ASD. Methods: Relevant databases including PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Science

Direct, and SCOPUS were searched using PICO question with time limit 5 years from 2011-2016. Of the

781 articles reviewed based on inclusion criteria (articles Systematic Review/ Meta-analysis of RCTs/ RCT,

CBT as the main treatment, anxiety as primary output, article is free and no duplication), only 2 articles

were fit and assessed critically. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2013) was used to assess

systematic review and meta-analysis and Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (CEBM) (2005) was

used to assess RCTs. Results: CBT (length: 6-32 weeks, duration: 60-120 minutes) was statistically

significant treatment to alleviate anxiety in children with ASD (7-17 years old) in moderate (d = 0.79; g = -

0.76) to large effect size (d = 0.94-1.30). Effect size did not significantly differ reported among child, parent

or clinician. Conclusion: CBT is highly recommended for children with ASD.

1 INTRODUCTION

Autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) or commonly

abbreviated as autism are a collection of

neurological disorders with characteristic problems

in social relations and communication that occur in

childhood (Siegel et al., 2014). Lack of interest in

participating in social contacts or activities, as well

as failure in communication or the use of appropriate

language are two common symptoms that occur in

children with ASD. This problem is compounded by

their limitations in making eye contact and facial

expression. Therefore, it cannot be denied if they

prefer to be alone and live in their own world

(March and Schub, 2016).

Although children with ASD generally have

problems in social aspects such as failure to initiate

communication and relationships, psychological

problems, especially anxiety are the main

comorbidities that often arise besides depression,

cognitive impairment and stereotypical behavior

(Storch et al., 2015). According to the results of

various studies and surveys mentioned that anxiety

disorders and specific phobias occur in more than

50% of cases of children with ASD. Followed by

other types of anxiety such as separation anxiety and

generalized anxiety in more than 20% of cases

(Muris et al., 1998; Leyfer et al., 2006; De Bruin et

al., 2007; Simonoff et al., 2008).

ASD is a lifelong disturbance that requires

continuation of medical therapy (Siegel et al., 2014).

Several survey results have revealed that one of the

continuing medical therapies that is widely accepted

by children with ASD is psycho-pharmacotherapy,

especially serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs),

which is almost 90%. Although SSRIs have been

clinically proven to be used to reduce anxiety in

children with ASD, the sustainability of this therapy

needs to be considered since the side effects caused

mainly changes in metabolism such as improper

weight gain with growth and development patterns

in a child's body can be very dangerous

(Sukhodolsky et al., 2013).

One of the best solutions that can be given that

involves interdisciplinary teams with the aim of

improving adaptive behavior and emotional well-

Pranata, G. and A. Istri Wulan Krisnandari D., A.

Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to Reduce Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0008199000050011

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of Indonesian National Nurses Association (ICINNA 2018), pages 5-11

ISBN: 978-989-758-406-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

5

being without side effects is cognitive behavioral

therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy or commonly

known as CBT is a therapy program that in the last

few decades have been an alternative solution to

address the anxiety problems experienced by

children with ASD because of the long-term benefits

offered. This therapy is useful since no previous

single remedy has proven effective in alleviating

anxiety as one of the core symptoms of ASD

(Hanson et al., 2007). The CBT program for anxiety

disorders is specifically designed to help children

with ASD identify the anxiety they experience, train

and encourage the use of adaptive behaviors and

self-awareness in responding to situations or

conditions that are the source of anxiety (Danial and

Wood, 2013). The two main focus and target of the

implementation of this therapy is the improvement

of the two body’s physiological functions, namely

cognitive functions such as anxiogenic cognitive

factors, and behavioral functions such as avoidance,

both of which are triggering factors for anxiety (Ung

et al., 2015).

The implementation of CBT basically rests on

two main assumptions namely behavior can be

influenced by cognitive activity and changes in

cognitive can affect behavior change (Dozois and

Dobson, 2001). Therefore, this therapy uses both

types of cognitive and associative methods as a

complementary approach. In CBT there are six

component methods, which are commonly

implemented. These components are related to one

another and consist of an assessment of the problems

faced both in nature and level, self-reflection,

training to restructure cognitive and affective

functions, management of anxiety, as well as

creating a new cognitive skills training schedule

(Shaker-Naeeni, Govender and Chowdhury, 2014).

Nowadays, studies of CBT for children has

developed rapidly and evaluated for the efficacy. For

example, in children who experience anxiety

disorders but not including children with ASD, CBT

has been applied in nearly 50 studies with a

randomized control trial design. Evaluations of these

studies show that CBT has had a positive effect with a

moderate effect sizes (ESs) on nearly 60% of

participants (Compton et al., 2004). However, in

children with ASD who experience anxiety, the

magnitude of the effect of this therapy varies or

differs from one another. Inconsistencies are seen in

the results of several studies that found small

therapeutic effects, while others found moderate to

strong effects. Hence, the purpose of this review was

to investigate and summarize the magnitude of CBT’s

effects in reducing anxiety in children with ASD.

2 METHODS

2.1 Literature Search

A systematic search on relevant databases such as

PubMed; CINAHL; Cochrane Library; Science

Direct and SCOPUS and reference lists of published

with time limit 5 years, 2011-2016 was conducted

using the keywords based on the PICO Question.

The entered keyword including the patient

population, intervention and the outcome (“autism

spectrum disorder in children” OR “autistic

spectrum disorder children” AND “cognitive

behavioral therapy” AND “anxiety”).

2.2 Selection of Studies

Studies were included in the literature review if they

meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) The design

or study method must be a Systematic Review/

Meta-analysis for RCT/ RCT or randomized

controlled trials or open trials. The design of studies

who do not meet the criteria such as case studies

were excluded; (2) Participants involved must be

children with ASD under the age of 18 years with a

diagnosis of ASD must be established through valid

and reliable measurements; (3) CBT must be the

main therapy; (4) Anxiety becomes the main output

and must be measured by psychometric instruments

that have been proven valid and reliable; (5)

Research articles must be published in English, are

open access and free to download, and there is no

duplication in the database.

2.3 Selection of Treatment Outcome

Measures

Based on the psychometrically sound properties and

the use of common anxiety severity scales in

children with ASD, the preferred list of outcome

measures need to be considered priori. Preferred

rating scales included Pediatric Anxiety Rating

Scale (PARS) (The Research Units On Pediatric

Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group, 2002),

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Child/

Parent or Clinical Severity Rating (ADIS-IV-C/P or

ADIS-IV-CSR) (Silverman and Albano, 1996),

Clinical Global Impression-Severity and

Improvement scale (CGI-Severity, CGI-

Improvement) (Guy, 1976), Multidimensional

Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) or with Parent

(MASC-P) (March, 1998), Revised Child Anxiety

and Depression Scales (RCADS) (Chorpita, Moffitt

and Gray, 2005; Sterling et al., 2015), Revised

ICINNA 2018 - The 1st International Conference of Indonesian National Nurses Association

6

Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS)

(Reynolds and Richmond, 1978), Child and

Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4 Anxiety Scale

(CASI-Anx) (Sukhodolsky et al., 2008), Screen for

Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED)

(Birmaher et al., 1999), and Spence Children’s

Anxiety Scale for Parent or Child (SCAS-P/C)

(Spence, 1998).

2.4 Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g

This study used Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g to measure

the large of treatment effect. For the study that used

Cohen’s d, the values of d = 0.2 indicate small effect

size, d = 0.5 indicate moderate effect size, and d =

0.8 indicate large effect size. Meanwhile, for the

study that used Hedges’ g, the values of g < 0.5

indicate a small effect size, g = 0.5-0.8 indicate

moderate effect size, and g > 0.8 indicate a large

effect size. Hedges’ g was used, as it appropriate for

check biases due to small sample sizes which is not

covered under Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988).

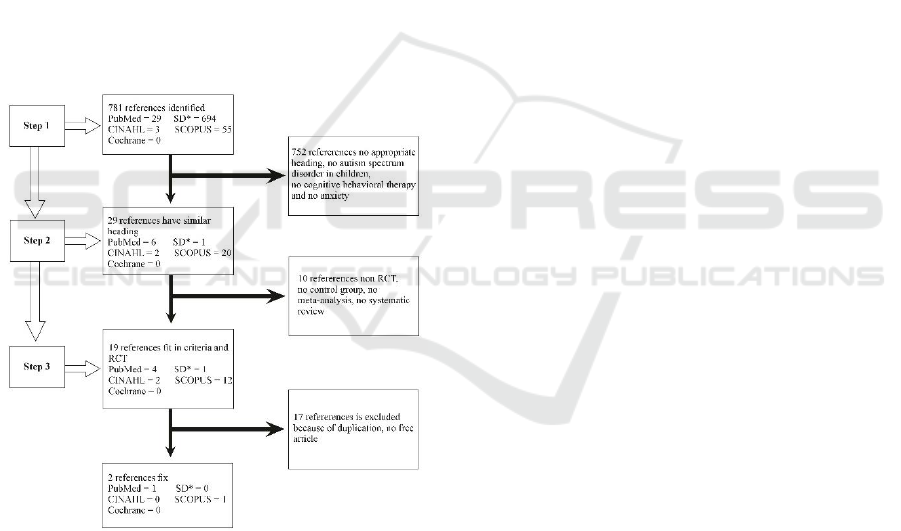

Note: SD* = ScienceDirect

Figure 1: Step-by-step search and selection strategies for

systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT of CBT for

anxiety in children with ASD.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Included and Excluded Trials

A total of 781 articles was identified through

electronic relevant databases of “PubMed”,

“CINAHL”, “Cochrane Library”, “Science Direct”,

and “SCOPUS”. Those articles were reviewed by

read the heading to find articles that fitted to

keyword. Seven hundred and fifty-two articles were

rejected and leaving only 29 articles whose titles

match the keywords. After inspection and check for

the abstract, 27 articles were excluded because they

did not meet the inclusion/ exclusion criteria and

were duplicates (see Fig. 1). The remaining 2

articles then were retrieved for further review. The

title of the articles selected were “a randomized

controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy

versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism

spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety by Storch,

et al. (2015)” and “a systematic review and meta-

analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety

in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum

disorders by Ung, et al. (2015)”. Critical appraisal

tools such as Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

(CASP) (2013) was used to assess systematic review

and meta-analysis article and Oxford Centre for

Evidence Based Medicine (CEBM) (2005) was used

to assess RCTs article. All of the search and

selection processes were carried out by the two

authors for 2 weeks.

3.2 Participants

Collectively, the 15 studies of RCT (2 open trial)

that included had a total of 542 participants. Two

hundred ninety-nine participants received CBT and

243 participants as control group and received the

following: treatment as usual (TAU, n = 52),

waitlisted (WL, n = 172), or enrolled in the Social

Recreational Program (SR, n =34). The sample size

of the studies ranged from 6 to 71 participants with

range of age varies from 7 to 17 or under 18 years

(M = 11.92 years). Of the studies that reported

gender distribution, most of the participants were

male (n = 447, 83.4%) and the remaining

participants were female (n = 89, 16.6%).

Of the studies that reported ASD diagnosis

distribution among its participants, 205 (41.7%)

participants were diagnosed with Asperger’s

syndrome, 159 (32.3%) participants were diagnosed

with autistic disorder, 89 (18.1%) were diagnosed

with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise

specified (PDD-NOS), and 39 (7.9%) participants

were labelled as “high functioning ASD”. In

established a true ASD diagnosis, both of studies

were same in applied a reliable measure of ASD by

used ADI-R, ADOS, or through medical records.

Of the studies that reported anxiety disorder

among its participants, 160 (32.3%) participants

Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to Reduce Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Literature

Review

7

were reported suffer social phobia, 133 (26.9%)

participants were reported suffer generalized anxiety

disorder (GAD), 79 (15.9%) participants were

reported suffer separation anxiety disorder (SAD),

42 (8.5%) participants reported suffer obsessive-

compulsive disorder (OCD), and 81 (16.4%)

participants reported suffer other comorbid disorder

such as specific phobia, panic disorder, attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), etc.

Of the studies that reported medication usage

among its participants, the following medications

were reported: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

(SSRI) or anti-anxiety or anti-depressant (n = 81;

32.9%), stimulant, atomoxetine, or guanfacine (n =

65; 26.4%), atypical anti-psychotic (n = 39; 15.9%),

alpha blocker (n = 6; 2.4%), anti-convulsion (n = 5;

2%), trazodone or mood stabilizer (n = 2; 0.8%), and

other psychotic or non-psychotic medication that

were not specified (n = 48; 19.5%).

3.3 Intervention Characteristic

CBT periods lasted from 6-32 weeks (M = 15.4

weeks) with duration 60-120 minutes. Therapy was

given by therapists who are experienced and highly

trained in CBT, or clinical psychologists or doctoral

psychology students who have clinical experience of

at least 1 year in using CBT to deal with anxiety in

children. Eight studies conducted CBT in individual

child sessions with or without parents, six studies in

group sessions with or without parents, and one

study conducted CBT both, in individual and group

sessions.

In general CBT has a method composed of 6

components. However, in this study there were only

3 reported components, namely cognitive

restructuring, psychoeducation and coping

mechanisms. Specifically, there are themes that are

trained in psychoeducation such as recognition of

anxious feelings in oneself and others, recognition of

anxiety triggers, recognition of somatic reactions to

anxiety, and others. As for coping mechanisms, the

themes being trained include coping skills,

relaxation techniques, creating a hierarchy of fears,

exposure to feared stimuli, and developing social

skills. Sessions of the therapy were often taught

through role play, social stories, structured

worksheets, visual and video modelling, etc.

Treatment protocols used in CBT were based on

manual and/or books that modified CBT to be

appropriate for children with ASD. Of the studies

that reported treatment protocols, the following type

were reported: Cool Kids, Facing Your Fears,

Behavioral Intervention for Anxiety in Children with

Autism (BIACA), Coping Cat, Multimodal Anxiety

and Social Skills Intervention (MASSI), and

Exploring Feeling or Building Confidence.

Meanwhile, for the control group they were only

received treatment as usual (TAU; e.g., psychosocial

or pharmacological treatment or no seek treatment),

social recreational program or even as waitlist.

3.4 Dependent Variables

Two articles were selected and assessed critically

used similar treatment outcome measures. The

primary anxiety outcome measures that were used

included: Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS),

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Child/

Parent or Clinical Severity Rating (ADIS-IV-C/P or

ADIS-IV-CSR), Clinical Global Impression-

Severity and Improvement scale (CGI-Severity,

CGI-Improvement), Multidimensional Anxiety

Scale for Children (MASC) or with Parent (MASC-

P), Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scales

(RCADS), Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety

Scale (RCMAS), Child and Adolescent Symptom

Inventory-4 Anxiety Scale (CASI-Anx), Screen for

Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED), and

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale for Parent or Child

(SCAS-P/C).

3.5 CBT Treatment Efficacy

CBT has proved reducing anxiety in children with

ASD. Of the two evidences, the result showed CBT

was statistically significant treatment to reduce

anxiety in children with ASD in moderate (d = 0.79;

g = -0.71 or -0.76 after removal of the two open trial

studies) to large effect size (d = 0.94-1.30). Effect

size did not significantly differ across anxiety

informant (among child (g = -0.60, 95% CI -1.17, -

0.03, z = -2.05, p < .05), parent (g = -0.82, 95% CI -

1.34, -0.30, z = -3.11, p < .01), or clinician (g = -

1.23, 95% CI -1.19, -0.55, z = -5.29, p < .001)) and

treatment modalities either in group sessions with or

without parents (g = -0.75, 95% CI -1.50, -0.003, z =

-1.97, p = .05) versus individual sessions with or

without parent (g = -0.62, 95% CI -0.92, -0.36, z = -

4.44, p < .01).

Based on the results of the diagnostic status

examination at post-treatment using the ADIS-C/P

instrument in the RCT study it was found that nearly

half (50%) of the participants in the treatment group

who received CBT had no longer experienced

anxiety, whereas in the control group who received

TAU, all participants were still experiencing

ICINNA 2018 - The 1st International Conference of Indonesian National Nurses Association

8

anxiety. Significant changes and improvements in

function were seen mainly in the subscale of

consciousness, cognition and communication. Based

on these results it can be concluded that a significant

effect was observed on the overall function of

autism by considering differences in measurement

results in parents and children after treatment.

Furthermore, significant differences between the

treatment and control groups were also detected in

the reduction in overall impairment of autism

function and the externalization of children's

behavior. However, based on the results of treatment

maintenance and re-examination one month after

treatment, there was no significant reduction

observed in anxiety on any measurement even

though significant improvements were detected in

the subscales of cognition, communication and

mannerism.

4 DISCUSSION

CBT is effective, acceptable and can be applied in

clinical setting since the effect size is moderate to

large. In study with RCTs, CBT was superior to

control waitlist, TAU, and social recreational

program and had a moderate effect size (g = -0.76).

This results were contrary with the previous study

that often reported lower treatment effect size

because of poor parent, clinician and child

diagnostic agreement on anxiety measures for

children (Ishikawa et al., 2007).

CBT as an alternative therapy has been

successful in reducing anxiety in children with ASD.

The success of this therapy in reducing anxiety may

be caused by the following two factors, namely the

CBT procedure which can be modified to match the

anxiety experienced by children with ASD, and the

CBT components implemented that contain high

cognitive and behavioral standards (Ung et al.,

2015). Treatment components adapted to meet the

needs of children with ASD reported by this review

were similar to the components reported by the

previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses (e.g.,

introspection, social skills development, use of

visual aids, systematic reinforcement, exposure to

feared stimuli, and creation of fear hierarchy). This

results suggest that these CBT components are still

commonly used to decrease anxiety in children.

The length of CBT’s session that was administer

until or over 32 weeks also factor that may

contribute to the successful reason of this therapy to

reduce anxiety in children with autism spectrum

disorder, as explained in the previous study (Fujii et

al., 2013). It is possible that the longer period of

CBT, the longer have had time to practice skills

learned, and the more robust effect of treatment. The

results of this review suggest that the length of time

span is an important factor that must be considered if

this therapy is expected to be able to give a positive

effect or even be applied to different settings.

The CBT program can be delivering by group

sessions or individual sessions with or without

parents. Both of this approaches are similarly

efficacious to reducing anxiety in children with

ASD. The results show the overlap in confidence

intervals revealed that they were not statistically

significant different. Ishikawa et al. (2007)

explained that implementation of CBT either

delivered in groups or individually with or without

parents not only provides benefits in the form of

normalization of anxiety symptoms through

increased adaptability. Moreover, the benefits can

also be seen in other aspects such as increased

motivation, acceptance, accountability, self-efficacy,

and support from peers or social. Another study

explained that CBT can help to alleviate impairment

and improving functional social responsiveness,

social skills, daily living skills, awareness, cognition

and communication (Storch et al., 2013, 2015).

CBT also has proved more safe and efficient than

pharmacotherapy. There were no reports that this

therapy is harmful. The cost-effectiveness analyses

results also have shown CBT seems a cost-effective

therapy to treat anxiety disorders in children with

ASD, if decreased anxiety level is used as an output

parameter (Van Steensel, Dirksen and Bögels,

2014).

5 CONCLUSIONS

CBT was statistically significant treatment to reduce

anxiety in children with ASD in moderate (d = 0.79;

g = -0.76) to large effect size (d = 0.94-1.30). Effect

size did not significantly differ reported among

child, parent or clinician. CBT is highly

recommended for children with ASD since this

therapy not only effective but also more safe and

cost effective.

REFERENCES

Birmaher, B. et al. (1999) ‘Psychometric properties of the

screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders

(SCARED): A replication study’, Journal of the

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry,

Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to Reduce Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Literature

Review

9

38(10), pp. 1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-

199910000-00011.

Chorpita, B. F., Moffitt, C. E. and Gray, J. (2005)

‘Psychometric properties of the revised child anxiety

and depression scale in a clinical sample’, Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 43(3), pp. 309–322. doi:

10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the

behavioural sciences, 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Hillsdale.

Compton, S. N. et al. (2004) ‘Cognitive-behavioral

psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in

children and adolescents: An evidence-based medicine

review’, American Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, 43(8), pp. 930–959. doi:

10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf.

Danial, J. T. and Wood, J. J. (2013) ‘Cognitive behavioral

therapy for children with autism: Review and

considerations for future research’, Journal of

Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(9), pp.

702–715. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31829f676c.

De Bruin, E. I. et al. (2007) ‘High rates of psychiatric co-

morbidity in PDD-NOS’, Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 37(5), pp. 877–886. doi:

10.1007/s10803-006-0215-x.

Dozois, D. J. A., and Dobson, K. S. (2001). Historical and

philosophical bases of the cognitive-behavioral

therapies. Dobson, Keith S. Handbook of Cognitive

Behavioral Therapies.

Fujii, C. et al. (2013) ‘Intensive cognitive behavioral

therapy for anxiety disorders in school-aged children

with autism: A preliminary comparison with

treatment-as-usual’, School Mental Health, 5(1), pp.

25–37. doi: 10.1007/s12310-012-9090-0.

Guy, W. (1976). Clinical global impressions, in ECDEU

assessment manual for psychopharm acology.

National Institute for Mental Health, Rockville.

Hanson, E. et al. (2007) ‘Use of complementary and

alternative medicine among children diagnosed with

autism spectrum disorder’, Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 37(4), pp. 628–636. doi:

10.1007/s10803-006-0192-0.

Ishikawa, S. I. et al. (2007) ‘Cognitive behavioural

therapy for anxiety disorders in children and

adolescents: A meta-analysis’, Child and Adolescent

Mental Health, 12(4), pp. 164–172. doi:

10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00433.x.

Leyfer, O. T. et al. (2006) ‘Comorbid psychiatric disorders

in children with autism: Interview development and

rates of disorders’, Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 36(7), pp. 849–861. doi:

10.1007/s10803-006-0123-0.

March, J. (1998). Manual for the multidimensional anxiety

scale for children. Mult-Health Systems, Toronto.

March, P. and Schub, T. (2016) ‘Autism spectrum

disorder: Quick lesson’, Cinahl Information Systems.

Muris, P. et al. (1998) ‘Comorbid anxiety symptoms in

children with pervasive developmental disorders’,

Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 12(4), pp. 387–393. doi:

PII S0887-6185(98)00022-X.

Reynolds, C. R. and Richmond, B. O. (1978) ‘What I

think and feel: A revised measure of children’s

manifest anxiety’, Journal of Abnormal Child

Psychology, 6(2), pp. 271–280. doi:

10.1207/s15327752jpa4303.

Shaker-Naeeni, H., Govender, T. and Chowdhury, U.

(2014) ‘Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety in

children and adolescents with autism spectrum

disorder’, British Journal of Medical Practitioners,

7(3). Available at: http://www.embase.com/search/

results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L600

271161.

Siegel, B. et al. (2014) ‘Autism spectrum disorders’,

Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences, 1, pp.

339–341. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385157-4.01067-8.

Silverman, W. K., and Albano A. M. (1996). The anxiety

disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV—child and

parent versions. Psychological Corporation, San

Antonio.

Simonoff, E. et al. (2008) ‘Psychiatric disorders in

children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence,

comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-

derived sample’, Journal of American Academy of

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), pp. 921–929.

doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f.

Spence, S. H. (1998) ‘A measure of anxiety symptoms

among children’, Behaviour Research and Therapy,

36(5), pp. 545–566. doi: 10.1016/s0005-

7967(98)00034-5.

Sterling, L. et al. (2015) ‘Validity of the revised children’s

anxiety and depression scale for youth with autism

spectrum disorders’, Autism, 19(1), pp. 113–117. doi:

10.1177/1362361313510066.

Storch, E. A. et al. (2013) ‘The effect of cognitive-

behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for

anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A

randomized, controlled trial’, Journal of the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Elsevier, 52(2), p. 132–142.e2. doi:

10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.007.

Storch, E. A. et al. (2015) ‘A randomized controlled trial

of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as

usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders

and comorbid anxiety’, Depression and Anxiety, 32(3),

pp. 174–181. doi: 10.1109/CCDC.2016.7531585.

Sukhodolsky, D. G. et al. (2008) ‘Parent-rated anxiety

symptoms in children with pervasive developmental

disorders: Frequency and association with core autism

symptoms and cognitive functioning’, Journal of

Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(1), pp. 117–128. doi:

10.1007/s10802-007-9165-9.

Sukhodolsky, D. G. et al. (2013) ‘Cognitive-behavioral

therapy for anxiety in children with high-functioning

autism: A meta-analysis’, Pediatrics, 132(5), pp.

e1341–e1350. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1193.

The Research Units On Pediatric Psychopharmacology

Anxiety Study Group (2002) ‘The pediatric anxiety

rating scale (PARS): Development and psychometric

properties’, Journal of the American Academy of Child

ICINNA 2018 - The 1st International Conference of Indonesian National Nurses Association

10

and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(9), pp. 1061–1069. doi:

10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006.

Ung, D. et al. (2015) ‘A systematic review and meta-

analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in

youth with high-functioning autism spectrum

disorders’, Child Psychiatry & Human Development.

Springer US, 46(4), pp. 533–547. doi:

10.1007/s10578-014-0494-y.

Van Steensel, F. J. A., Dirksen, C. D. and Bögels, S. M.

(2014) ‘Cost-effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral

therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety disorders

in children with autism spectrum disorder’, Research

in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(2), pp. 127–137. doi:

10.1016/j.rasd.2013.11.001.

Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to Reduce Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Literature

Review

11