Marital Quality: An Empirical Comparison of Two Unidimensional

Measures

Soerjantini Rahaju

1,2

, Nurul Hartini

1

and Wiwin Hendriani

1

1

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga

2

Faculty of Psychology, University of Surabaya

Keywords: Quality Marital Index, Relationship Assessment Scale, Indonesian Form

Abstract: Marital quality is a construct that is often interchangeably used with other constructs such as marital

satisfaction, marital adjustment and marital happiness. This condition brought impact to the variations in its

measurement. This research intended to validate the two most frequently used marital quality inventories,

the Quality Marital Index (QMI) and Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) in the Indonesian version using

factorial structure and psychometric properties. The participants of this study were 81 heterosexual couples

(N═162) with average marriage duration 16.6 years, and all had a minimum of one child. Confirmatory

Factor Analysis using Lisrell 9.3 revealed that RAS Indonesian form had better internal structure than QMI

Indonesian form. The model of QMI was a poor fit, and the model of RAS with only 5 items was a close fit.

RAS-Indonesian form had two items with low standardized factor loadings. Cultural bias in wording and

other reasons for these findings are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

The quality of marriage is a factor that has an

important role in the success of a marriage, as being

a major predictor of long-lasting marriage (Karney

and Bradbury,1995). It affects the wellbeing and life

satisfaction of individuals (Fincham and Beach,

2010; Robles, 2014) and also affects the wellbeing

of children in a marriage through better parenting

(Malinen, et al., 2010). Poor marital quality has

negative effects on individual wellbeing (Proulx,

Helms, and Buehler, 2007), individual health (Smith

and Baucom, 2017). Poor marital quality for those

not yet divorced had more severe negative impact

than marriage that ended in divorce (Gustavson,

2013). It led marital quality to become a topic in

many marriage researches.

Marital quality has two form constructs, a

multidimensional construct and a unidimensional

construct. As a multidimensional construct, marital

quality referred to a marriage condition

characterized by good criteria including good

adaptation, adequate communication, high marital

happiness, integration, intimacy, consensus,

pleasure, mutual companionship, and marital

satisfaction (Spanier and Lewis, 1980; Johnson, et

al., 1986; Hassebrauck and Fehr, 2002; Schneider,

2007; Chonody, et al., 2016). As a unidimensional

construct, marital quality emphasized the individual

global evaluation of the conditions of marriage,

dyadic relationships, and their overall functioning

(Spanier and Lewis, 1980; Norton, 1983; Fincham

and Bradbury, 1987; Sabatelli, 1988; Schneider,

2007). Since it was a global subjective evaluation,

the term marital quality was also used for marital

satisfaction and marital happiness (Jackson, et al.,

2014).

The extensive coverage from the marital quality

construct brought an impact to the measurement of

marital quality. There were many scales that could

be used to measure marital quality, named Kansas

Marital Satisfaction (KMS), ENRICH, Quality

Marital Index, Relationships Assessment Scale,

Couples Satisfaction Inventory, and many others.

Each scale has its unique characteristics, and should

be considered when using it.

There were two main categories in marital

quality construct. The first was the unidimensional

and the second was the multidimensional. Each

approach had pros. The multidimensional construct

of marital quality covered the complexity of the

marital conditions that contributed to the quality of

the marriage (Fowers and Owenz, 2010). The

unidimensional construct was more useful for theory

180

Rahaju, S., Hartini, N. and Hendriani, W.

Marital Quality: An Empirical Comparison of Two Unidimensional Measures.

DOI: 10.5220/0008587001800186

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 180-186

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

and research development because it avoided

overlapping with other variables such as

communication, conflict and others (Fincham and

Bradbury, 1987).

The condition of marriage in Indonesia is

indicated by some problems, which were related to

poor marital quality. Data from the High Court of

East Java Province (2017) showed that most divorce

cases happened because of couples’ disharmony and

too many disputes in marriage relationships. Almost

31.5% of problems that made couples divorce in

2014-2016 were due to poor marital quality. Other

problems in marriage and family that also increased

recently such as infidelity and domestic violence

could be indicated in poor marital quality, since

there was no happiness in couples’ relationships.

1.1 Marital Quality Measurements

Two scales of marital quality that had been used

widely in many researches because of their pros in

the number of items were Relationships Assessment

Scale (RAS) and Quality Marital Index (QMI).

These scales contained 6-7 items. It was more

practical in the operationalizations, compared to

MSS, which had 73 items (Schneider, 2007).

Another marital quality scale was the Kansas

Measurement Scale, which had the fewest items,

only three items, and meant confirmatory factor

analysis could not be performed. Therefore, this

research focused on comparison of the two marital

quality measurements, which were QMI and RAS

Indonesian version.

QMI and RAS English version both had good

psychometric properties, such as strong reliability,

and had already been used widely in many

researches. Chonody, et al. (2016) reported that

QMI had strong reliability (α = .94), and RAS also

had good reliability (α = .86). Heyman, Sayers, and

Bellack (1994) identified that the two scales (RAS

and QMI) both had excellent correlations with

relevant variables such as dyadic adjustment. But

Chonody, et al. (2016) also mentioned that it still

needed further testing to determine its applicability

with a diverse sample, as the original sample was

drawn from Midwest backgrounds. Therefore, this

study aimed to compare the validation of the two

measurements using Indonesian wording and

Indonesian subjects.

1.2 Marital Quality Measurements in

Indonesia

Identifying underlying causes and factors that affect

marital quality requires a robust and culturally

appropriate measurement, as marital quality is a

cultural topic (Shen, 2015). In doing so, an adapted

version of the marital quality scale is needed.

Only few researches exist on adaptation of

marital quality measurement Indonesian version, e.g.

research by Rumondor (2013), and Wahyuningsih,

et al. (2013). The tool developed by Rumondor

(2013) measured marital satisfaction for young

adults. It was built by combining three marital

measurements already developed: Dyadic

Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976), ENRICH marital

satisfaction (Fowers and Olson, 1993) and the

Marriage Satisfaction Questionnaire (Sadarjoen,

2004). It had 58 items and covered 9 dimensions

(communication, balance of role sharing, openness,

agreement, intimacy, social intimacy, sexuality,

financial, spiritual). The other marital measurement

that developed in Indonesia was Indonesian Moslem

Marital Quality Scale (IMMQS). This scale focused

on measuring marital quality in Muslim marriage.

The 13-item IMMQS consisted three sub-scales: the

7-item friendship, the 3-item satisfaction with

children, and the 3-item harmony.

The two marital measurements explained above

used a multi-dimensional construct of marital

quality, and had specific utilization. The one from

Rumondor (2013) was for early adulthood stage, and

the other from Wahyuningsih (2013) for Muslim

couples. Therefore, this research intended to analyze

marital quality measurement as a unidimensional

construct for general use, since the unidimensional

construct of marital quality is more useful for

research than a multi-dimensional construct

(Fincham and Bradbury, 1987).

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

The population of this study was married couples,

who were not in commuter marriage, were still in

their first marriage, and already had at least one

child. All couples lived in the city of Surabaya.

Samples were obtained through the snowball

sampling method.

The participants used in this study were 81

Indonesian heterosexual married couples (N=162

Marital Quality: An Empirical Comparison of Two Unidimensional Measures

181

subjects). Couples were still married, not in

commute marriage, and already had at least one

child. Participants were recruited through

information from various friends who had access to

ask participants for willingness to join the research.

Husbands and wives filled in the questionnaires

separately and only questionnaires filled in

completely were used in this study. Husbands’ mean

age was 44.1 years old (SD = 7.341) and wives’ was

40.5 years old (SD = 8.74). Average marriage’

duration was 15.38 years (SD = 7.85). Husbands’

education, 64.2% had Bachelor’s, Master’s or

Doctoral degree. Wives’ education, 66.6% had

Bachelor’s, Master’s or Doctoral degree. All

husbands were fully employed, and 81.5% of wives

were fully employed. Most participants were

Muslims (66.7%). Most participants (70%) had 1-2

children and many of their first children were above

12 years old.

2.2 Measurement

2.2.1 Quality Marital Index

The Quality Marital Index created by Norton (1983)

was a 6-item scale measuring the conditions of the

marriage based on global subjective evaluation

about the condition of marriage through the use of

global semantic words such as “good” and “strong”

(Norton 1983). Items scored using a seven-point

scale anchored at 1 = strongly disagree and 7 =

strongly agree. The sixth item was measured on a

10-point Likert type scale, anchored with 1 = very

low and 10 = very high. For data analysis the 10-

point scale of item six was converted to 7-point, so

all items had the same scale.

QMI correlated very strongly with Dyadic

Adjustment Scale and had high internal consistency,

good convergent and discriminant validity

correlations (Heyman et al., 1994; Chonody et al.,

2016).

In this study, QMI measured unidimensional

marital quality (N = 162, M = 38.83, SD = 4.60).

2.2.2 Relationship Assessment Scale

The Relationship Assessment Scale created by

Hendrick (1988) was 7-item scale as a unifactorial

measure of global relationship satisfaction focusing

on how well the partner meets their needs, how well

the relationship compares to others, and regrets

about the relationship. All items scored using a

Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (e.g. how well does

your husband/wife fulfill your needs?) All items

were favorable items, except item number 4 (e.g.

how often you wish you were not involved in

relations with your spouse) and 7 (e.g. how many

problems in your relationships with your spouse),

which were unfavorable.

RAS measured unidimensional marital quality

(N=162, M= 26.59, SD = 2.87)

2.3 Procedure and Data Analysis

The procedure of test adaptation in this study was

done through the process of selecting a translator,

doing the forward-backward translation, evaluating

if the content of the test and the wording in a second

language could measure the same construct as the

first language checking the equivalence of the test in

the second language and culture, and conducting

validation analysis. These processes were conducted

based on International Test Commission Guidelines

for Translating and Adapting Tests (2017). For

validation analysis this study used a contemporary

approach in which all validities should be

conceptualized under one framework and construct

validity included content, internal structure and

relations to other variables (Cook and Beckman,

2006; Brown, 2010; Rios and Wells, 2013).

Data was analyzed using confirmatory factor

analysis (CFA) to test the internal structure and run

with Lisrell 9.3 student’s version.

3 RESULT

The result of this study is described in contents,

internal structure, and relations to other variables.

3.1 Content Analysis

Evidence for content in this research was collected

based on expert judgment evaluation related to

construct definition, the clearance of the tools’

purpose, and the wording of items. In this research,

there were three experts in clinical and marriage

research. There was some input from the experts

related to wording, such as a suggestion to use the

words “Mr. and Mrs.” replacing the word “you”, in

both scales. Other suggestions from experts on the

QMI scale were changing the word “harmony” to

“stable” (item number 2, e.g. My relationships with

spouse is very stable), “one team” to “part of team”

(item number 5, e.g. I feel part of a team with my

spouse). For RAS scale, the experts’ suggestions for

wording were using the word “relasi” not

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

182

“hubungan” (Indonesian language) for translation of

“relationships”.

There were notes from experts related to the

word “good” in item number 1 of QMI (e.g. we have

a good marriage), as it could be interpreted by

Indonesian subjects too widely. Another note from

an expert for item number 4 of RAS (e.g. how often

do you wish you were never involved in relations

with your spouse) as using the word “often” and

“never” in one sentence could be confusing when

answering.

3.2 Internal Structure

The confirmatory factor analysis for the Quality

Marital Index Indonesian form was a poor fit for the

theoretical model (X

2

/df = 82.43/9, RMSEA = .227,

GFI = .843, CFI = .928).

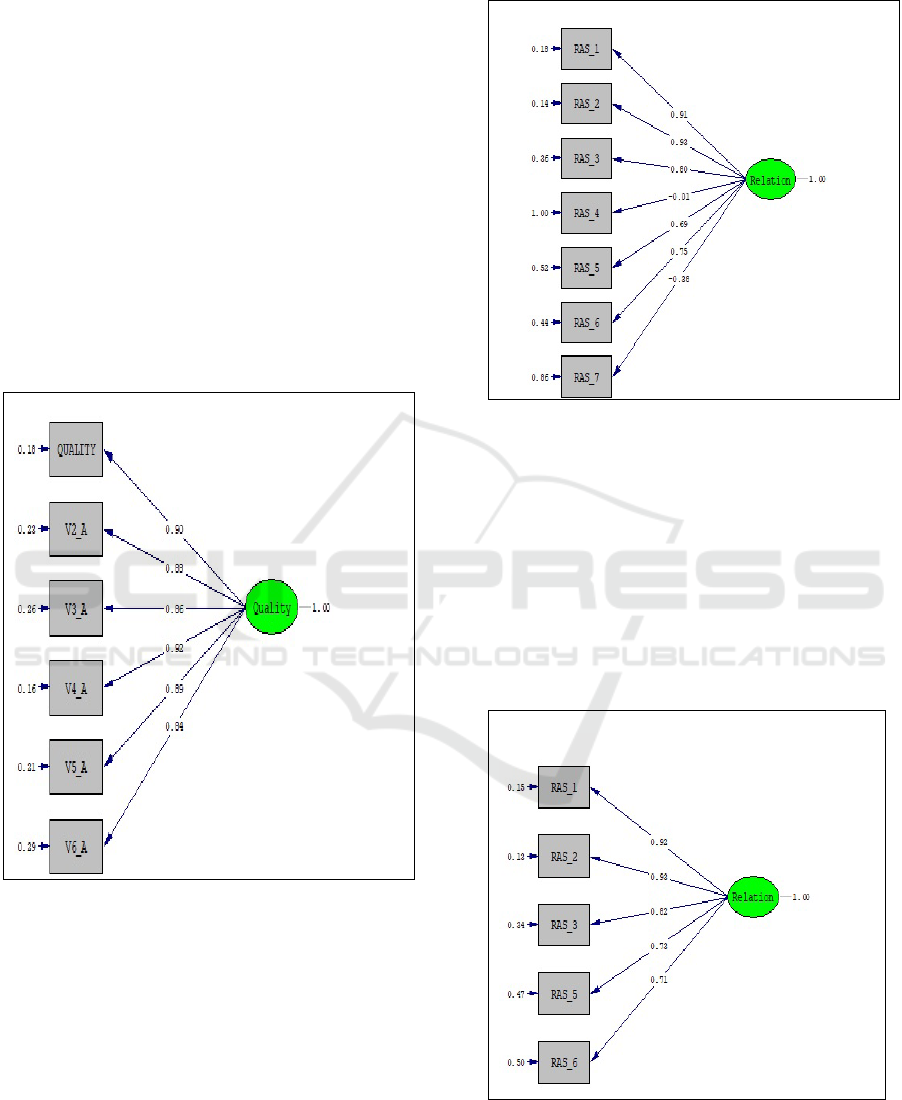

Figure 1: CFA of Quality Marital Index.

As illustrated in Figure 1, even though all items

had strong factor loadings for marital quality, the

model was not fit. For reliability, this scale had

strong composite reliability (α = .955).

For Relationships Assessment Scale (RAS)

Indonesian form the confirmatory factor analysis

was run twice. The first trial was using all items (7

items) as the original RAS. The second trial was

using only 5 items for RAS Indonesian form with

only items that had strong factor loadings.

Result for CFA of RAS Indonesian form in the

first trial showed a poor fit (X

2

/df = 76.14/14,

RMSEA = .17, GFI = .881, CFI = .897) (see Figure

2).

Figure 2: CFA of Relationship Assessment Scale (7 items)

As illustrated in Figure 2, standardized factor

loadings for relationship quality for items number 1,

2, 3, 5 and 6 ranged from .75 – .92 meaning these

five items had high contribution to latent variable,

and were recommended for use in the scale without

any revision at all. However, items number 4 and 7

had low factor loadings (see Figure 2). These two

items showed a weak contribution to the latent

variable. Especially, item number 4 showed not only

weak but reverse correlation to the latent variable.

Figure 3: CFA of Relationship Assessment Scale (5 items)

Since there were two items with low factor

loadings, item number 4 and item number 7 (see

Marital Quality: An Empirical Comparison of Two Unidimensional Measures

183

Figure 2), then we did the second trial. The second

trial was using only five items. Item number 4 and

item number 7 were dropped.

Results for CFA of RAS Indonesian form with

only 5 items in the second trial showed a moderate

fit (X

2

/df = 11.5/5, RMSEA = .09, GFI = .973, CFI =

.989) (see Figure 3).

The score of composite reliability also showed

improvement (first trial α = .842, second trial α =

.912). It meant that Relationship Assessment Scale

Indonesian form could use only 5 items. Using the

whole 7 items of Relationship Assessment Scale

needed revision on item number 4 and item number

7.

3.3 Relation to Other Variables

Since QMI and RAS were the same global

measurement of marital quality, so for the evidence

of relations to other variables the two measurements

would be correlated. The correlation score of QMI

and RAS would be the evidence of validation for the

relations to other variable aspects. QMI Indonesian

form and 7-items RAS Indonesian form had

significant positive correlation (r = .499, ρ = .00).

QMI Indonesian form and 5-items RAS Indonesian

form had significant positive correlation (r = .752, ρ

= .00).

4 DISCUSSION

Results from the confirmatory factor analysis

showed that both scales (QMI Indonesian form and

RAS Indonesian form) fit poorly to the theoretical

model. It meant that the data did not give the same

model as the English version. The QMI Indonesian

form and RAS Indonesian form could not measure

the marital quality as the original one did.

These weaknesses could come from many factors

such as the meaning of wording and relevancies

within an Indonesian context. QMI Indonesian form

measured global evaluation about marriage using

semantic words (e.g. we had a good marriage). The

word “good marriage” in this item could be biased in

interpretation, because it covered too many

dimensions of marriage. Other semantic words in

QMI items could be biased such as stable (e.g. my

relationship with my spouse is very stable), and the

word strong (e.g. our marriage is strong). Stable and

strong could be understood in many different

conditions by each subject. It might also be

culturally different.

The confirmatory factor analysis of RAS

Indonesian form with the 7 items, as in the original

one, revealed that the model was also a poor fit. It

found that there were two items with weak

contribution to the latent variable. The weak items

were items number 4 and number 7 (see Figure 2).

These weaknesses could come from the negative

statement of these two items. The wording in item

number 4 was confusing because it used

contradiction in a word in one item (often and

never). One of the expert judgements had already

mentioned it too. Item number 4 (How often do you

wish you hadn’t gotten into this relationship?) was

difficult to answer because it could be biased in its

meaning.

Item number 7 (How many problems are there in

your relationship?) was also not a good item,

because of its weak contribution to the latent

variable. It asked about marital problems evidence,

and it had weak factor loadings. It could be

interpreted that marital problems could not always

be indicators of poor relationship quality. A good

marriage would have problems too.

In the second trials of CFA for RAS Indonesian

form with only 5 items (dropping items 4 and 7) it

seemed to support the fitness of this scale. The

reliability of this scale was also improved. Even

though not giving a good fit, this 5-item RAS

Indonesian form showed a close fit. It could

conclude that a 5-item RAS Indonesian form

measured marital quality better than the 7-item RAS

Indonesian form, and the QMI Indonesian form. For

future research, using a complete RAS Indonesian

form still needs revisions for items number 4 and 7.

QMI Indonesian form and 7-item RAS

Indonesian form correlated only moderately, but

became strong when correlated with a 5-item RAS

Indonesian form. These findings could be related to

the improvement of internal structure of a 5-item

RAS Indonesian form. The moderate correlation of

QMI Indonesian form and RAS Indonesian form

could indicate that each had a specific focus. Both of

these scales measure unidimensional marital quality,

but in QMI, marital quality is measured globally by

using semantic words (e.g. good marriage, strong

relationships, stable marriage). In RAS, marital

quality was evaluated in more specific aspects (e.g.

fulfillment need, love, satisfaction). Using these

scales should consider the specific characteristics of

each scale.

This study was done only with participants

already married for mostly 15 years and who not

need marriage interventions. Therefore, it did not

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

184

result from discrimination scores from these two

measures.

REFERENCES

Brown, T., 2010. Construct Validity: A Unitary Concept

for Occupational Therapy Assessment and

Measurement. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational

Therapy, [e-journal] 20(1), pp. 30-42.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-1861(10)70056-5

Chonody, J.M., Gabb, J., Killian, M., and Dunk-West, P.,

2016. Measuring Relationship Quality in an

International Study: Exploratory and Confirmatory

Factor Validity. Research on Social Work Practice, [e-

journal] 28(8), pp. 1-11.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516631120

Cook, D.A., and Beckman, T.J., 2006. Current Concepts

in Validity and Reliability for Psychometric

Instruments: Theory and Application. The American

Journal of Medicine, [e-journal] 119, pp. 166.e7-

166.e16.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.036

Fincham,F.D., and Bradbury,T.N., 1987. The Assessment

of Marital Quality : A Reevaluation. Journal of

Marriage and Family, [e-journal] 49(4), pp.797-809.

https://doi.org/10.2307/351973

Fincham, F.D., and Beach, S.R.H., 2010. Marriage in the

New Millennium : A Decade in Review. Journal of

Marriage and Family, [e-journal] 72, pp. 630-649.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00722.x

Fowers, B.J., and Owenz, M.B., 2010. A eudaimonic

theory of marital quality. Journal of Family Theory &

Review, [e-journal] 2(4), pp. 334–352.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00065.x

Ghozali, I., and Fuad, 2014. Structural Equation

Modeling. Teori, Konsep dan Aplikasi dengan

Program Lisrel 9.10. 4th ed. Semarang : Badan

Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro.

Gustavson, K., Nilsen, W., Ørstavik, R., and Røysamb, E.,

2014. Relationship quality, divorce, and well-being:

findings from a three-year longitudinal study. The

Journal of Positive Psychology, [e-journal] 9(2),

pp.163–174.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.858274

Hassebrauck, M., and Fehr, B., 2002. Dimensions of

Relationship Quality. Personal Relationships, [e-

journal] 9(3), pp. 253-270.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.00017

Hendrick, S. S., 1988. A Generic Measure of Relationship

Satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, [e-

journal] 50(1), pp. 93–98.

https://doi.org/10.2307/352430

Heyman, R.E., Sayers, S.L., and Bellack, A.S., 1994.

Global Marital Satisfaction Versus Marital Adjustment

: An Empirical Comparisan of Three Measures.

Journal of Family Psychology, [e-journal] 8(4), pp.

432-446.

High Court of East Java Province Indonesia, 2017. Faktor-

Faktor Penyebab Terjadinya Perceraian. Surabaya :

High Court of East Java Province.

ITC, 2018. International Test Commision Guidelines for

Translating and Adapting Tests. 2

nd

ed. International

Journal of Testing, [e-journal] 18(2), pp. 101-134.

https://10.1080/15305058.2017.1398166

Jackson, J.B., Miller, R.B., Oka, M., and Henry, R.G.,

2014. Gender Differences in Marital Satisfaction : A

Meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, [e-

journal] 76, pp. 105-129.

Johnson, D.R.,White, L.K., Edwards, J.N., Booth, A.,

1986. Dimensions of Marital Quality Toward

Methodological and Conceptual Refinement. Journal

of Family Issues, [e-journal] 7(1), pp. 31–49.

https://doi.org/10.1177/019251386007001003

Karney, B.R., and Bradbury, T. N., 1995. The

Longitudinal Course of Marital Quality and Stability :

A Review of Theory , Method , and Research.

Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), pp. 3–34.

Malinen, K., Kinnunen, U., Tolvanen, A., Jamk, A.R.,

Wierda-Boer, H., and Gerris, J., 2010. Happy Spouses,

Happy Parents? Family Relationships Among Finnish

and Dutch Dual Earners. Journal of Marriage and

Family, , [e-journal] 72(2), pp. 293-306.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00700.x

Norton, R., 1983. Measuring Marital Quality : A Critical

Look at the Dependent Variable. Journal of Marriage

and Family, , [e-journal] 45(1), pp. 141–151.

https://doi.org/10.2307/351302

Proulx, C.M., Helms, H.M., and Buehler, C., 2007.

Marital Quality and Personal Well-Being : A Meta-

Analysis. Journal of Marriage & Family, , [e-journal]

69(3), pp. 576-593.

Rios, J., and Wells, 2013. Validity evidence based on

internal structure. Psicoterma, [e-journal] 26(1), pp.

108-116.

https://doi.org/10.7334/psicoterma2013.260

Robles, T.F., 2014. Marital quality and health :

Implications for marriage in the 21st century. Current

Directions in Psychological Science, , [e-journal]

23(6), pp. 427-432.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414549043

Rumondor, P.C.B., 2013. Pengembangan Alat Ukur

Kepuasan Pernikahan Pasangan Urban. Humaniora, 4

(2), pp. 1134-1140.

Sabatelli, R. M., 1988. Measurement Issues in Marital

Research : A Review and Critique of Contemporary

Survey Instruments. Journal of Marriage and Family,

[e-journal] 50(4), pp. 891–915.

http://doi.org./10.2307/352102

Sadarjoen, S. S., 2004. Model Kualitas Perkawinan

Berdasarkan Kepegasan Pasangan dan Gaya

Penyelesaian Konflik Perkawinan: Studi Eksplanatif

terhadap Pasangan Perkawinan Eksekutif Muda Pada

Usia Perkawinan Sepuluh Tahun Pertama di Kota

Bandung dan Jakarta, Ph.D. University Padjadjaran.

Bandung.

Schneider, B., 2007. Critical Evaluation and Conceptual

Organization of Marital Fucntioning Measures.

Graduate Student Journal of Psychology, [e-journal]

Marital Quality: An Empirical Comparison of Two Unidimensional Measures

185

9, pp. 38-47.

Shen, A.C., 2015. Factors in the marital relationship in a

changing society A Taiwan case study. International

Social Work, [e-journal] 48(3), pp. 325–340.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00208 72805051735

Smith, T. W., and Baucom, B. R. W., 2017. Intimate

relationships, individual adjustment, and coronary

heart disease: Implications of overlapping associations

in psychosocial risk. American Psychologist, [e-

journal] 72(6), pp. 578-589.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000123

Spanier, 1976. Measuring Dyadic Adjustment: New Scales

for Assessing The Quality of Marriage and Similar

Dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family, [e-journal]

38(1), pp. 15-28.

https://doi.org./10.2307/350547

Spanier, G. B., and Lewis, R. A., 1980. Marital Quality : A

Review of the Seventies. Journal of Marriage and

Family, [e-journal] 42(4), pp. 825–839.

https://doi.org./10.2307/351827

Wahyuningsih, H., Nuryoto, S., Afiatin, T., and Helmi, A.,

2013. The Indonesian Moslem Marital Quality Scale:

Development, Validation, and Reliability.: The Asian

Conference on Psychology and the Behavioral

Sciences. Osaka, Japan. The International Academic

Forum

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

186