The Influence of Masculine Ideology and Gender Role Orientation on

Self-esteem of Pastors’ Husbands of the Batak Karo Protestant

Church

Karina Meriem Beru Brahmana

1

, Suryanto

1

and Bagong Suyanto

2

1

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Social Sciences and Political Sciences, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Masculine Ideology, Gender Role Orientation, Self Esteem.

Abstract: This study aimed to examine the influence of masculinity ideology and gender role orientation towards self-

esteem of pastors’ husbands in Batak Karo Protestant Church (GBKP). Being a pastor’s husband in GBKP

community is not easy, as he should maintain relationships with family and congregation. The demands of a

wife’s time-consuming duties mean the husband is taking care of household chores. This demand affects the

husband’s orientation while doing household chores. Moreover, this demand generally affects his self-

esteem as a man. As a man of Karo tribe, the pastor’s husband has been exposed to patrilineal culture since

an early age. In this culture, a man is expected to accomplish his role as a man. Gender role socialization

since childhood by family or community forms the ideology of being a man or so-called masculinity

ideology. A total of seventy-nine pastors’ husbands of GBKP were interviewed, with the following criteria:

having a minimum one year of marriage and having a child, from Karo tribe, not a priest, becoming a

GBKP fellowship since they are single. The study found that masculinity ideology did not significantly

affect the priests’ husbands’ self-esteem, nevertheless gender role orientation significantly affected the

husbands.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

The Karo is one of many tribes found in North

Sumatra that values patriarchal culture, in which

supreme power is pre-dominated by men. As a tribe

with patriarchal culture, the Karo acknowledges and

distinguishes people based on sex, not only because

of physical traits but also their influence on society

(Bangun, 1981). These differences can be viewed

from the rights and responsibilities of each sex. For

example, men particularly work as carpenters, while

women simply become housewives. In Karo culture,

men hold vital roles, as they become powerful

leaders to make decisions, especially in traditional

ceremonies. On the other hand, women traditionally

tend to be inferior to men (Tarigan, 2009).

In Karo culture, performing a less-appropriate

gender-related task can impair one’s dignity. A man

raising children in the midst of ceremony, for

instance, may lose his dignity. A man who often

performs such activity or other women’s duties is

called pa diberu or man who is commanded by his

wife or a womanish man (Bangun, 1981). When a

Karo man is imposed or volunteered to challenge

opposite roles of cultural demands, it will lead to

inner conflicts, including insecure feelings, and even

bring greater impacts such as shame, anger or

contention with others.

The Karo culture generally determines position

in social hierarchy based on sex. The Karo also

places men higher than women. Family, called jabu

in Karo, never used names from the wife, but from

the husband. This reflects how the Karo places man

or husband as a decision-maker (Bangun, 1981).

Man’s position in the social hierarchy applies to

all Karo men, including husbands of GBKP pastors.

A husband in the Karo tribe is expected to be a

leader and bring a positive influence to his family.

Moreover, a patrilineal system encourages men to be

more capable in anything than women (Bangun,

1981).

However, in fact, the condition is different when

a man marries a female pastor of GBKP. As a

230

Brahmana, K., Suryanto, . and Suyanto, B.

The Influence of Masculine Ideology and Gender Role Orientation on Self-esteem of Pastors’ Husbands of the Batak Karo Protestant Church.

DOI: 10.5220/0008587602300238

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 230-238

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

member of Lord’s family, the pastor’s husband is

responsible for assisting his wife during the church

service. Naras (the name of a pastor’s husband) is

expected to show his concern to congregation and

community. He is also expected to fully support his

wife based on his gifts and capability, equip him-self

to support the service provided by his wife in the

spiritual field and daily life, remind his wife as

God’s servant to carry out her service in the

congregation, and not becoming a stumbling block

during the service (PPWG GBKP, 2014).

Consequently, it is assumed that being a husband of

a GBKP priest is not easy and requires

responsibility.

Based on the interview’s results, moral

responsibility given to the pastor’s husband is due to

the wife’s immense services as shepherd, teacher

and leader, and her constantly mobile service duties.

As the congregation needs more attention, it causes

the husband to feel unnoticed. Moreover, a lot of

church duties carried out by the wife lead to their

unproductivity in doing household chores, either as a

wife or housewife, such as cooking, taking care of

the home, raising children, as well as other domestic

chores. Therefore, it is expected that a husband

(naras) would do such chores more often than his

wife, either voluntary or obliged.

This unbalanced condition (where the pastor is

also a wife who has a bustling agenda, and the

husband is hoped to be a chaperone and assist his

wife) is likely to cause difficulties for husbands. In

this case, a husband is required to take their ego

away as a man and be helpful in assisting the wife’s

services by taking care of children, helping in

household chores (cooking, washing, ironing and

others), and willing to deliver his wife.

The differences occurring between cultural

expectation and reality result in the husband being

helpless, passive, having low self-esteem, lacking

confidence, less developed and even feeling

depressed due to being unproductive or jobless. This

is also supported by interviews with several

husbands who reveal that the situation they are

experiencing causes them to be sensitive, irritable,

less willing to engage in the services performed by

their wives, unwilling to assist in household chores

and feeling inferior.

Self-esteem is a positive self-impression,

including positive self-esteem and confidence

(O’Neil, 2008). Man commonly hides his insecure

feeling because it can threaten his power in

relationships and work. Hiding feelings is related to

gender role as expected in society. Wood and Eagly

(2002) argued that men are expected to exhibit their

agentic or masculine traits, such as self-confidence,

superiority, and be active, independent, and able to

face the pressure and optimistic. Nevertheless, the

unexpected gender role would discourage men’s

self-esteem.

Concerning gender role, men’s self-esteem level

is commonly determined by various factors, one of

them is masculinity ideology (Blazina, 2001).

According to Blazina (2001), a feeling of

worthlessness or low self-esteem is caused by

inability to negotiate different gender roles in

different contexts and situations. On the other hand,

Pleck (1995) proposed that masculinity ideology is

men’s belief in adhering to culturally defined as

standard male behavior in order to support the

internalization of a cultural belief system regarding

his masculinity and gender.

Masculinity ideologies are the primary way for

boys and men to culturally live out with patriarchal

and sexist values, which have negative consequences

in interpersonal relationships with the person or

others. This relationship can be disrupted if men find

that their engaged ideology differs from the reality

(O’Neil, 2008). Based on the statement above, this

condition also occurs in the pastor’s husband, in

which the masculinity principle has been

internalized and its practice differs in marriage. His

inability to be a breadwinner and his responsibility

in helping with household chores are factors that

contradict the ideology adopted since childhood.

One of the negative consequences of rigid and

sexist masculinity ideology is when feelings of

worthlessness and low self-esteem occur among men

(Blazina, 2001). Blazina stated that feeling occurs

because men are unable to negotiate diverse gender

roles encountered in different contexts and

situations. Moreover, Pleck et al. (1993) asserted

that masculinity ideology constructed among men

leads to negative consequences towards self-esteem

degradation as well as other psychological aspects.

Besides masculinity ideology, another factor that

leads to a husband’s self-esteem is gender role

orientation (Cate and Sugawara, 1986; Lamke, 1982;

Mullis and McKinley, 1989). Performing new roles

is commonly influenced by worldview or belief

when viewing certain roles. Some people assume

that men bearing children is a common thing, while

others think that this is uncommon for men.

Individual beliefs in performing work and family

duty are generally known as gender role orientation

(Bird, et al., 1984).

For traditional men, being a primary care giver

or doing household chores is inappropriate.

Moreover, men also have a higher level or

The Influence of Masculine Ideology and Gender Role Orientation on Self-esteem of Pastors’ Husbands of the Batak Karo Protestant Church

231

superiority than women. Thus, it is not proper for

men to carry out feminine roles as mentioned.

However, non-traditional men commonly tend to

view this work differently. For them, performing

feminine-related roles is not a taboo, especially

when it can increase happiness and help their wife.

Research on men’s household-related gender

roles suggests that men who perceive household

chores as appropriate work would receive more

responsibility to perform tasks related to a children’s

caregiver, serving meals and other household works,

than men who support gender role diversity between

men and women (Bird, et al., 1984).

Moreover, a study by Helmreich and Spence

(1978) revealed that an individual with an

androgynous gender role generally has a more

positive image than in a masculine, feminine and

undifferentiated gender role. Some researchers (Cate

and Sugawara, 1986; Lamke, 1982; Mullis and

McKinley 1989; Rust and McCraw, 1984) have

proposed that individuals with masculine and

androgynous gender orientations are generally

correlated with high prestige.

This study is not only to provide the different

conditions experienced by the pastor's husband

associated with self-esteem, but also beneficial for

GBKP (Karo Protestant Batak Church) as an

organization. GBKP is expected to arrange and

develop future planning for the husband regarding

the increasing number of women who become

pastors.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

1. Does masculine ideology affect GBKP pastors’

husbands’ self-esteem?

2. Does gender role orientation affect GBKP

pastors’ husbands’ self-esteem?

2 METHOD

A quantitative research was conducted, in which the

collected data was analyzed using SEM-PLS

(Structural Equation Model-Partial Least Squares)

Student version 3.0.

SEM-PLS was used to explore existing theories

and identify key variables or to predict certain

constructs (Sholihin and Ratmono, 2013). This

method was also used for research that uses a

relatively small sample size.

2.1 Research Subjects

A total of seventy-nine husbands of GKBP pastors

were the subjects of this research, with criteria:

having been married at least for a year and having a

child; indigenous people of Karo tribe; and members

of GBKP since they were single and not working as

active pastors, both inside and outside GBKP.

2.2 Techniques of Data Collection

There were three variables used in this research,

namely masculine ideology, gender role orientation

and self-esteem. Each variable was measured using a

different scale. Variable of masculine ideology was

measured using Thompson and Pleck’s The Male

Role Norms Scale (MRNS) (1986). Gender role

orientation variable was measured using the Sex

Role Orientation Inventory (SROI) developed by

Tomeh (1978), which used non-traditional questions

to reflect on a general shift in society's views

(Tomeh, 1978). Meanwhile, self-esteem variable

was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem

Scale (RSE) (Rosenberg, 1979).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Reliability and Validity of Scale

Trial

Before conducting scale tests, the researcher first

prepared the scales according to the variables used

in this research. After finding the suitable scales, the

researcher asked 6 subject matter experts to evaluate

the scales. Before the scales were distributed, the

researcher sent a permit application letter from the

researcher’s home faculty to the Moderamen of the

Karo Protestant Batak Church (GBKP). Then, it was

approved for data retrieval.

The following are the results of reliability and

validity of the scales using Confirmatory Factor

Analysis (CFA) of the three research scales that had

been tested on 40 respondents. The Confirmatory

Factor Analysis was conducted using Lisrel version

8.50. The t-values listed in parameters ( and 1-)

were examined to obtain a reliable value of items in

Lisrel. The parameters were considered significant if

the value of t >1.96.

Based on the test results of masculine ideology

scale using Lisrel 8.50, it was found that 17 out of

26 items of masculine ideology were valid and 9

items were void/invalid, with reliability of 0.733.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

232

The results of gender-oriented scale show that 16 out

of 28 items of gender role orientation were valid,

while the rest were null, with reliability of 0.670.

Meanwhile, 4 out of 10 items of self-esteem were

valid and 6 items were invalid, with reliability of

0.64.

3.2 Descriptive Analysis of Research

Data

According to Ghozali (2014), descriptive analysis is

an technique used to find the description of data.

This technique is not used to test the research

hypothesis, but to present the data along with

statistical calculations in order to clarify the state or

characteristics of data to be processed using the

SPSS program. The researcher created a category of

norms to facilitate in interpreting the scores obtained

from the responses. Azwar (2008) explained that the

categorization is based on the norm distribution

model, with the assumption that the score of

respondents in the group is respondents’ score

estimation in a normally distributed population. The

categorization in this study was divided into three

groups; high, medium and low.

The following table is the result of descriptive

analysis of research variables:

Table 1: Descriptive Analysis of Masculine Ideology

Variable.

N Min Max Mean Std. Dev

MascIdeo 79 45 102 77.2278 11.60675

StatusNorm 79 22 54 41.1899 6.73696

Tou

g

hness 79 8 23 16.6709 3.64699

AntiFe

m

79 11 29 19.3671 4.07990

Valid N 79

The results of statistical calculations showed that

the mean of masculine ideology variable is 77.23.

This suggests that the husbands’ masculine ideology

is categorized moderate.

The indicator of normality status represents the

attitudes and beliefs in carrying out gender roles as

men in accordance with the norms prevailing in the

culture or society. The indicator of toughness

represents how men should display their strong and

tough figure physically and mentally. The last

indicator of anti-femininity represents the

compulsion of men to avoid feminine activities or

roles.

Table 2: Descriptive Analysis of Gender Role Orientation

Variable.

N Min Max Mean Std. Dev

Gender Role O

r

79 40 65 51.89 4.84

Wife

/

Mothe

r

79 12 23 18.19 2.00

Husband

/

Fathe

r

79 7 12 9.76 1.13

Problems 79 7 15 11.94 1.49

E

q

ualit

y

79 9 16 12 1.59

Valid N 79

The results of statistical test showed that the

mean of gender role orientation variable is 51.89.

This indicated that the husbands’ gender role

orientation is high. High level indicates that in

general, the husbands’ gender role orientation is

non-traditional.

Table 3: Descriptive Analysis of Self-Esteem Variable.

N Min Max Mean Std. Dev

HD 79 9 16 12.35 1.41

Valid N 79

The result of statistical test showed that the mean

of self-esteem variable is 12.35. This suggested that

the husbands’ self-esteem is categorized high.

3.3 Description of the Results

This research was analyzed using Smart PLS 3

student version. PLS test is a method of analysis that

is not based on assumptions. The following is the

result of the PLS analysis.

3.3.1 Outer Model Testing

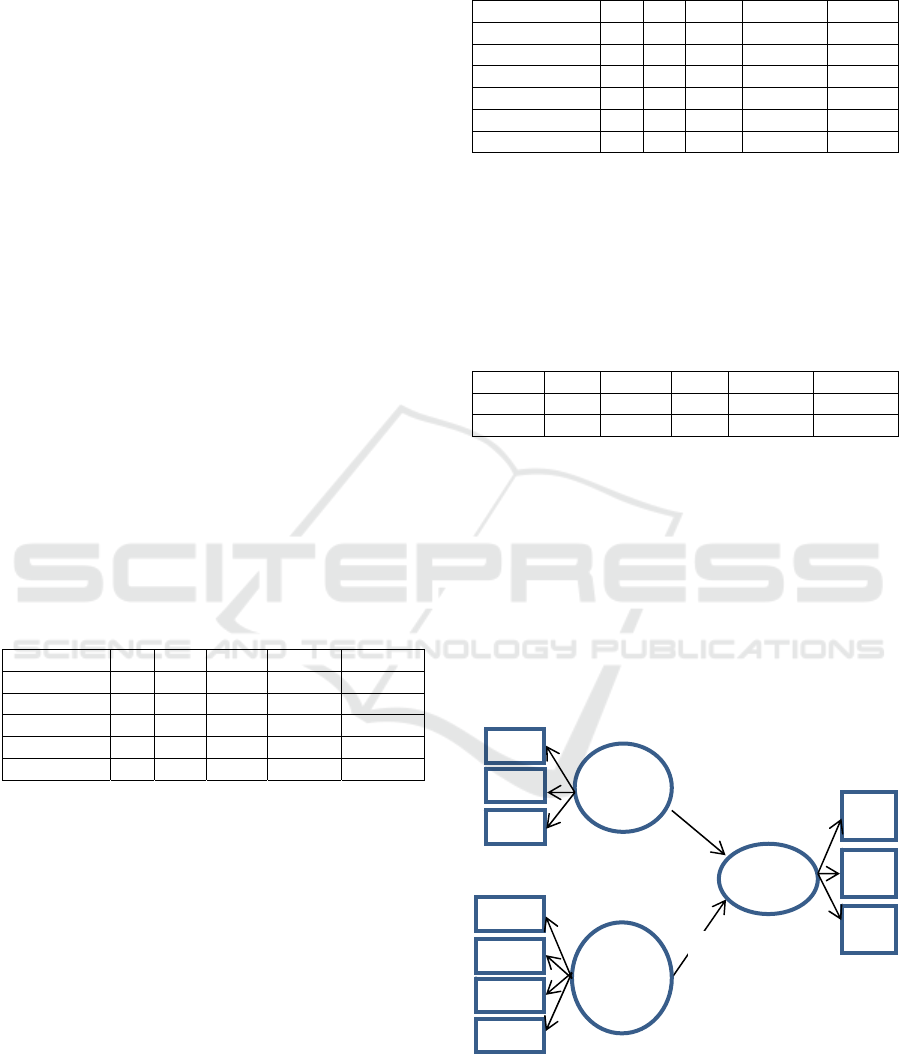

Figure 1: Results of Outer Model.

008

Ideolog

i

Maskul

AF 0 53

SN 0 98

TN

Harga

Diri

065

Ite

m 1

Ite

m 2

Ite

m 3

Orienta

si

Peran

Gender

ISIB

K

S

I

PSI 0 79

SA

0.22

The Influence of Masculine Ideology and Gender Role Orientation on Self-esteem of Pastors’ Husbands of the Batak Karo Protestant Church

233

0.

a. Convergent Validity

The results of convergent validity can be seen from

loading factor and t-test values. The loading factor

value is considered valid if the value is more than

0.5 (Chin, 1998 in Ghozali, 2014: 39).

Table 4: Results of Convergent Validity of Research

Variables.

Variables Indicators/Items Loading

Factors

Results

Masculine

Ideology

AF 0.53 Vali

d

SN 0.98 Vali

d

TN 0.40 Vali

d

Gender

Role

Orientation

Wife. Mothe

r

0.82 Vali

d

Eq. Husband.

Wife

0.75 Valid

Prob. Husband.

Wife

0.79 Valid

Husband. Fathe

r

0.70 Vali

d

Self-

Esteem

SE1 0.94 Vali

d

SE2 0.61 Vali

d

SE3 0.40 Vali

d

According to Hair et al. (1998) the loading factor

of convergent validity above is acceptable.

b. Construct Validity

The next measurement model aims to calculate the

Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which is the

value that indicates the magnitude of indicator

variant contained in its latent variable. The construct

is considered to have ideal construct validity if the

Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value is above

0.5 (Ghozali, 2008).

Table 5: Results of Construct Validity on All Variables.

Variables

Average Variance

Extracted (AVE)

Self-Estee

m

0.47

Masculine Ideology 0.46

Gender Role Orientation 0.59

The table shows that the AVE values in all

variable constructs were ranging from 0.4 – 0.5.

Thus, all latent variables had sufficient validity

(Ghozali, 2008).

c. Discriminant Validity

The results of discriminant validity test (cross

loading value) showed the value of cross loading in

each indicator was ranging from 0.389 - 0.98, where

each indicator had a higher loading construct value

compared to other construct loading values. It

indicated that all indicators in each variable had

greater correlation than those with other variables.

Therefore, the variable passed the discriminant

validity test.

Table 6: Results of Value Discriminant with Cross

Loading of All Variables.

Latent

Const

Indicators

Self-

esteem

Mas.

Ideo

Gender

Role

Orien

Self-

esteem

HD1 0,94 0,11 0,32

HD2 0,61 0,05 0,12

HD3 0,39 0,20 0,05

Gender

Role

Orient

Wife.

Moth

0,26 0,30 0,82

Hus. Fath 0,20 0,24 0,70

Kes 0,25 0,13 0,75

Per 0,14 0,24 0,79

Masc.

Ideology

AF -0,03 0,40 0,13

SN 0,13 0,98 0,29

TN 0,01 0,50 -0,12

d. Reliability (Goodness of Fit)

Table 7: Results of Construct Reliability.

Variables

Cronbach's

Alpha

Composite

Reliability

Masculine Ideology 0.70 0.69

Gender Role Orientation 0.76 0.85

Self-estee

m

0.44 0.70

The results of data reliability obtained composite

reliability value of > 0.6. It can be inferred that all

variables were reliable (Hartono and Abdillah,

2014).

3.3.2 Inner Model Testing

Inner model testing was conducted through two

stages of goodness of fit and research hypothesis

tests. The results can be seen in Figure 2.

a. Goodness of Fit Testing

Analysis of inner model was conducted to ascertain

whether the constructed structural model has been

accurate or not. In evaluating, the inner model can

be seen from several indicators:

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

234

1. Determinant Coefficient (R

2

)

Inner model testing is conducted by referring R-

square, which serves as goodness of fit model test.

Inner model test can be seen from the value of R-

square on the equation between latent variables. The

value of R

2

represents how exogenous

(independent/independent) the variable in the model

is able to explain the endogenous variable

(dependent/bound). Chin (in Jogiyanto, 2011)

explains the criteria of the R

2

value limits in three

categories, namely R

2

=

0.67 (good), R

2

= 0.33

(medium) and R

2

= 0.19 (low).

Table 8: R-Square Value.

Variable R S

q

uare Ex

p

lanation

Self-esteem 0.09 Low

The table shows that the value of masculine

ideology influence and gender role orientation to

self-esteem was 0.09 (9%), while the remaining 91%

was explained by other variables outside the

research scope.

2. Predictive Prevalence (Q2)

In addition to R-square, the model can also be

evaluated by looking at the value of Q-square. The

value of Q-square can be established with the

following calculation: Q2 = 1 - ((1-0.09) = 0.91.

Based on the calculation results, it can be seen that

the value of Q-square was 0.91 (Q2 >0). The result

indicated that masculine ideology and gender role

orientation had a good level of prediction of self-

esteem.

b. Hypothesis Testing

From the results of hypothesis testing it can be

concluded that there is no significant direct influence

of masculine ideology on self-esteem, but there is a

significant direct effect of gender role orientation on

self-esteem.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Masculine Ideology Does Not Affect

Self-Esteem of the Husbands of

GBKP Pastors

This research rejected the hypothesis of masculine

ideology affecting self-esteem of the husbands of

GBKP pastors. It suggests that masculine ideology

does not affect the condition of husbands’ self-

esteem; therefore other factors need to be

investigated. This is, of course, contradictory to

some research results suggesting that masculine

ideology influences self-esteem (Blazina 2001;

Pleck, et al., 1993).

The masculine ideology according to Pleck

(1995) is a belief in the importance of a person

following a predetermined standard of male

behavioral culture, and is engaged to support the

internalization of a cultural belief system of male

masculinity and gender. Masculine ideology is the

0.23

Ideologi

Maskulin

AF0.78

SN2.05

TN0.96

HargaDiri

Item1

Item2

Item3

Orientasi

Peran

Gender

ISIB2.64

K

SI2.02

PSI2.37

SA2.67

2.38

Figure 2: Result of Inner Model.

The Influence of Masculine Ideology and Gender Role Orientation on Self-esteem of Pastors’ Husbands of the Batak Karo Protestant Church

235

main way for boys and men to fulfill the sexist and

patriarchal values that generally have negative

consequences in their interpersonal relationships

with others (O'Neil, 2008; Pleck, 1995).

Masculine ideology, according to Levant (in

Mellinger & Levant, 2014), has been socialized and

instilled by parents, teachers and peers through

social interactions in the form of reinforcement,

punishment and observation. The masculine

ideology informs, encourages and limits boys (and

male adults) to conform to the norms of the

prevailing masculine role by adopting certain

socially approved masculine behaviors and avoiding

prohibited behaviors (Levant, in Mellinger &

Levant, 2014). If a boy or male adult is unable to

fulfill the values of the expected masculine ideology

of his environment or culture, according to Blazina

(2001), it can bring negative consequences of the

emergence of feelings of worthlessness or

inferiority.

Blazina (2001) revealed that feeling of

worthlessness or low self-esteem occurs because

men are unable to negotiate different gender roles in

different contexts and situations. This statement is

also supported by Pleck (in Pleck, et al, 1993), who

argued that the process of a male’s masculine

ideology formation also negatively affects the

decrease of self-esteem and other psychological

aspects.

The results of interviews conducted by

researchers with several husbands of GBKP pastors

showed that there were differences or contradictions

between the existing roles with the values that have

been instilled since childhood. The inability to

become the main breadwinner and the necessity to

assist in domestic housekeeping are contradictory to

the ideology as a man who has been embraced and

socialized by the culture and environment since

childhood. This ultimately raises feelings of

worthlessness or low self-worth. This finding is

consistent with the statement expressed by Good,

Borst and Wallace (1994), that failure to meet

cultural expectations associated with masculine

ideology can generally be detrimental to men

because men generally use cultural expectations as a

standard for the validation of their own masculinity.

However, the results of the research turned out

quite different. According to the results of the study,

masculine ideology embraced by husbands of GBKP

pastors was categorized medium, but their self-

esteem was high. These findings are contrary to the

phenomenon discussed above. In contrast, the

findings of this study are consistent with an

innovative research conducted by Robertson and

Verschelden (in Good, Borst and Wallace, 1994).

The research conducted by Robertson and

Verschelden (in Good, Borst and Wallace, 1994)

involved couples consisting of fathers who stayed at

home and working mothers (a couple with an

inverted role). They found that household fathers did

not tend to feel less masculine and more feminine

than those found in the general population. In

addition, the subjects of Robertson and

Verschelden’s study also did not feel different from

general people associated with self-esteem or

psychological well-being.

The household fathers revealed that they had a

greater satisfaction of life than general people, as the

couples felt that their children would benefit from

their current family structure. Therefore, the children

would be more flexible in carrying out their gender

roles, and it did not distinguish them as adults. From

these descriptions, it can be inferred that the conflict

of gender roles performed by the research subjects

with the prevailing masculine ideology do not lower

the husbands’ self-esteem.

The self-esteem possessed by the Karo tribe,

especially males, is the result of the formation that

has been passed down continuously through every

generation. Men in the Karo tribe have a special and

distinguished position, so any behavior or deed must

reflect such privilege. The patrilineal kinship system

adopted by the Karo tribe means the position of men

is higher than women. Ownership of the clan is

strong evidence of the male identity in the Karo tribe

that has been socialized since childhood by parents.

The results of the Karo Indo's 1977 seminar (in

Brahmana, 2003) revealed that Karo people

generally have special features, such as being honest

and courageous, unwilling to interfere, persevering,

polite in practice, tolerant and upholding self-

esteem. The Karo tribe considers self-esteem as the

most important element. Individuals of the Karo

tribe are generally respected and maintain their pride

greatly. For the sake of defending their self-esteem,

they are willing to go every possible way and suffer.

4.2 Gender Role Orientation Affects

Self-Esteem of the Husbands of

GBKP Pastors

In everyday life, both men and women are often

faced with situations in which they must perform

tasks or jobs that are inconsistent with their gender

roles. For example, women who are supposed to

play roles in taking care of households in fact must

act as a breadwinner in the family because of the

husband’s inability to do so. Or men who are

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

236

supposed to play the role of breadwinner in the

family but in fact carry out many roles of parenting

and other domestic chores.

These gender-contradictory roles can be

perceived differently by each individual. Some think

that it is something normal and some do not. The

perspective or belief of the individual (in this case

the male) in establishing his or her normal role is

known as gender-oriented orientation (Bird, et al.,

1984). According to Raguz (1991) the orientation of

gender roles is defined as a person's perception of

masculinity and femininity within themself. The

orientation of gender roles is seen as a continuum

sequence of traditional gender roles (looking at the

roles of men and women as separate and not

separate) to non-traditional gender roles

(characterized by flexibility in the division of roles

of men and women).

Based on the findings of Bem (1974), individuals

are generally divided into four main categories of

gender role orientation: masculine, feminine,

androgynous and undifferentiated. The androgynous

individual generally exhibits high masculine and

feminine characteristics, whereas in the

undifferentiated individuals the characteristics of the

two traits tend to be low. Research by Bem and his

colleagues found that psychologically individuals

whose gender role orientation is androgynous are

generally better able to adapt to different gender

roles so as to adequately demonstrate adaptive

behavior towards situations regardless of their

masculine or feminine connotations.

Related to gender role orientation, Marcia (1966,

1967, 1976) and his colleagues have developed

Erikson's Bipolar Model by adding a second variable

such as a crisis - in addition to commitment. Crisis

refers to when individuals are actively involved in

choosing alternatives, questioning prior choices and

beliefs. The situation of the crisis cannot be

separated from the various situations in individual

life, especially men who are often faced with roles

that are contrary to their gender roles.

Using a different gender role orientation scale

Spence et al. (1975) and Wetter (1975) found that

individuals with high levels of masculinity and

femininity (androgyny) had the highest levels of

self-esteem, while individuals with no masculine or

feminine orientation (undifferentiated) had the

lowest confidence levels. In addition, Wetter (1975)

found that only masculinity scores were positively

correlated with male and female self-esteem,

whereas femininity values were negatively

correlated with women's self-esteem (r = - .11, p

<.04).

In addition, studies conducted by Helmreich and

Spence (1978) also found that individuals whose

gender role orientation is androgynous generally

have a more positive self-image than men with

masculine, feminine or undifferentiated gender

orientations. Some researchers (Cate and Sugawara,

1986, Lamke, 1982, Mullis and McKinley, 1989,

Rust & McCraw 1984) have shown that in general

individuals with masculine and androgynous gender

role orientations are associated with high self-

esteem.

This is also consistent with the results of this

study, where gender-oriented roles tend to be high in

pastors’ husbands, meaning that husbands of pastors

generally have a non-traditional gender role

orientation. In other words, the pastor's husband is

generally not problematic in carrying out feminine

roles so that his self-esteem also tends to be high.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the research results some conclusions can

be drawn, such as: there is no influence between

masculine ideology and self-esteem on husbands of

pastors in GBKP and there is a significant influence

between gender role orientation and self-esteem on

husbands of pastors in GBKP. The limitations in this

study are related to the context of the research.

Because of the specific context of the research, the

results cannot be generalized to other tribes in

Indonesia.

AKNOWLEDGEMENT

The study was supported by a research grant from

Direktorat Jenderal Penguatan Riset dan

Pengembangan Kementerian Riset, Teknologi, dan

Pendidikan Tinggi Republic of Indonesia, based on

research contract number: 017/K1.1/LT.1/2018.

REFERENCES

Azwar, S., 2008. Penyusunan skala psikologi. Yogyakarta:

Pustaka Pelajar

Bangun, P., 1981. Pelapisan Sosial di Kabanjahe.

Disertasi. Ilmu Antropologi Sosial Universitas

Indonesia: Tidak Diterbitkan

Bem, S. L., 1974. The measurement of psychological

androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 42(2), pp. 155-162.

The Influence of Masculine Ideology and Gender Role Orientation on Self-esteem of Pastors’ Husbands of the Batak Karo Protestant Church

237

Brahmana, P., 2003. Daliken si telu dan solusi masalah

sosial pada masyatakat karo: kajian sistem

pengendalian sosial. Fakultas Sastra Jurusan Sastra

Indonesia: Universitas Sumatera Utara

Bird, G., Bird, G., and Scruggs, M., 1984. Determinants of

family task sharing: A study of husbands and wives.

Journal of Marriage and Family 46, pp. 345-355.

Blazina, C., 2001. Analytic psychology and gender role

conflict: the development of the fragile masculine self.

Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training,

38(1), pp. 50-59.

Cate, R. and Sugawara, A.I., 1986. Self-role orientation

and dimensions of self-esteem among middle

adolescents. Sex-Roles, 1, pp. 145-158.

Ghozali, I., 2008. Aplikasi analisis multivariate dengan

program spss. Semarang: Badan Penerbit Universitas

Diponegoro

Ghozali, I., 2014. Structural equation modeling, metode

alternatif dengan partial least square (pls). Edisi 4.

Semarang : Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro.

Good, G.E., Borst, T.S., and Wallace, D.L., 1994.

Masculinity research: a review and critique. Applied

and Preventive Psychology, 3, pp. 3-14.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., and Black, W.C.,

1998. Multivariate data analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle

River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hartono, J., and Abdillah, W., 2014. Partial least square.

Yogyakarta : Andi.

Helmreich, R.L., and Spence, J.T., 1978. Masculinity &

femininity. their psychological dimensions, correlates,

and antecedents. University of Texas Press, Austin,

TX.

Jogiyanto, H.M., 2011. Metodologi penelitian bisnis. Edisi

empat. BPFE. Yogyakarta.

Lamke, L.K., 1982. The Impact of sex-role orientation on

self-esteem in early adolescence. Child Development,

53, pp. 1530-1535.

Marcia, J.E., 1966. Development and validation of ego

identity status. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 3, pp. 551-558.

Marcia, J.E., 1967. Ego identity status: relationship to

change in self-esteem, "general maladjustment” and

authoritarianism. Journal of Personality, 35, pp. 118-

133.

Marcia, J.E., 1976. Manuscript in preparation for

publication. Simon Fraser University.

Mellinger, C., and Levant, R.F., 2014. Moderators of the

relationship between masculinity and sexual prejudice

in men: friendship, gender self-esteem, same-sex

attraction, and religious fundamentalism. Arch Sex

Behav, 43, pp. 519–530

Mullis, R. L., and McKinley, K., 1989. Gender-role

orientation of adolescent females: effects of self-

esteem and locus of control. Journal of Adolescent

Research, 4, pp. 505-516.

O’Neil, J.M., 2008. Summarizing 25 years of research on

men's gender role conflict using the gender role

conflict scale: new research paradigms and clinical

implications. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, pp.

358-445. doi: 10.1177/0011000008317057

Pleck, J.H., 1995. The gender role strain paradigm: an

update. In: R. F. Levant and W. S. Pollack Eds. A new

psychology of men. New York: Basic Books. pp.11-32.

Pleck, J.H., Sonnenstein, F.L., and Ku, L.C., 1993.

Masculinity ideology and its correlates. In: S. Oskamp

and M. Costanzo Eds. Gender issues in social

psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. pp.85-110.

PPWG GBKP 2014. Bahan Kursus Calon Pertua Diaken

GBKP Periode 2014-2019. Kabanjahe: Percetakan

GBKP Abdi Karya Kabanjahe.

Raguz, M., 1991. Masculinity and femininity: an empirical

definition. Drukkerij Quickprint BV, Nijmegen.

Sholihin, M., and Ratmono, D., 2013. Analisis SEM-PLS

dengan WrapPls 3.0 untuk hubungan nonlinier dalam

penelitian sosial dan bisnis. Yogyakarta: Penerbit

ANDI

Spence, J.T., Helmreich, R.L., and Stapp, J., 1975. Ratings

of self and peers on sex-role attributes and their

relations to self-esteem and conceptions of masculinity

and femininity. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 32, pp. 29-39.

Tarigan, S., 2009. Lentera kehidupan orang karo dalam

berbudaya. Medan.

Thompson, E.H., and Pleck, J.H., 1986. The structure of

the male norms. American Behavioral Scientist, 29,

pp. 531-543.

Tomeh, A.K., 1978. Sex-role orientation: an analysis of

structural and attitudinal predictors. Journal of

Marriage and the Family, 40 (May), pp. 341-354.

Rust, J. O., and McCraw, A., 1984. Adolescence, 19, pp.

359-366.

Rosenberg, M., 1979. Conceiving the self. New York:

Basic Books.

Wetter, R.E., 1975. Levels of self-esteem associated with

four sex role categories. Paper presented at the

Eighty-third Annual Convention of the American

Psychological Association, Chicago.

Wood, W., and Eagly, A., 2002. A cross-cultural analysis

of the behavior of women and men: implications for

the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin,

128, pp. 699–727.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

238