The Proliferation of Smartphones and their Effects on Improving the

Vocabulary of Indonesian Learners of Arabic

Yusring Sanusi Baso

1

, Rusnadi Padjung

1

and Prastawa Budi

1

1

Institute of Quality Assurance and Educational Development, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

Keywords: Smartphone, disruption era, vocabularies, learners of Arabic.

Abstract: This article aims to describe the use of the smartphone as a media to improve the mastery of students’ Arabic

vocabulary (mufradat). The participants in this study are students who are studying Arabic for the second and

the third years of the Arabic at Hasanuddin University. The number of participants is 32 and 33 students for

the respective batch. The researcher has created a mufradat database in an html-based interactive application,

which is easily accessed to via a smartphone or tablet. The testing of media effectiveness in improving

mufradat mastery is done through two experimental and control groups. Both groups can use PC facilities

available at the computer lab to access mufradat database. Both groups can also use their smartphones to

access the online interface. The difference is only in the memorization report of the mufradat and the

competency test. Experimental group uses smartphone media to report their memorization, while control

group reports theirs through a daily vocabulary record and was tested by using written test. The results show

that experimental group indicates better mastery than control group. The average memorization of the

experimental group is 1432 words while control group only reaches an average of 532 words.

1 INTRODUCTION

Arabic learning systems in Indonesia are like endemic

diseases. This crisis shows poor learning

performance, low quality of teaching and lack of

educational resources to support the learning process.

This can be seen from the number of students who can

have proper Arabic language knowledge and skill.

This condition is not much different from Arabic

education in the Middle East (UNESCO, 2012).

Arabic learning is also currently dealing with the

4.0 technology era. This era of disruption has shown

a tremendous gap between the way of life of the

Indonesian learners of Arabic and how educators

(teachers and lecturers) expect them to learn. This sort

of disruption requires changes in the attitudes and

responsibilities of the Arabic language instructors, the

skills needed, and their professional role.

It is undoubtedly said that the teaching of Arabic

in Indonesia in the last few decades has not been able

to improve Arabic learning system significantly. One

of the data that supports this statement is that the

number of study programs (Arabic) with an A

accreditation status is still 16.35% or 26 of the total

159 S1 (Bachelor Degree) study programs recorded

at the Indonesian National Higher Education

Accreditation Board or BAN-PT (BANPT, 2018).

The condition of an accredited study program is still

less experienced by other study programs. Arabic

study program accredited A is 16.35% or 26 of 159.

English Study programs accredited A are 8.92% or 44

of 493, Japanese study programs are 21.95% or 9 of

41, and Chinese study programs reach 12.50% or 2 of

16 recorded in BAN-PT. This can be seen in table 1:

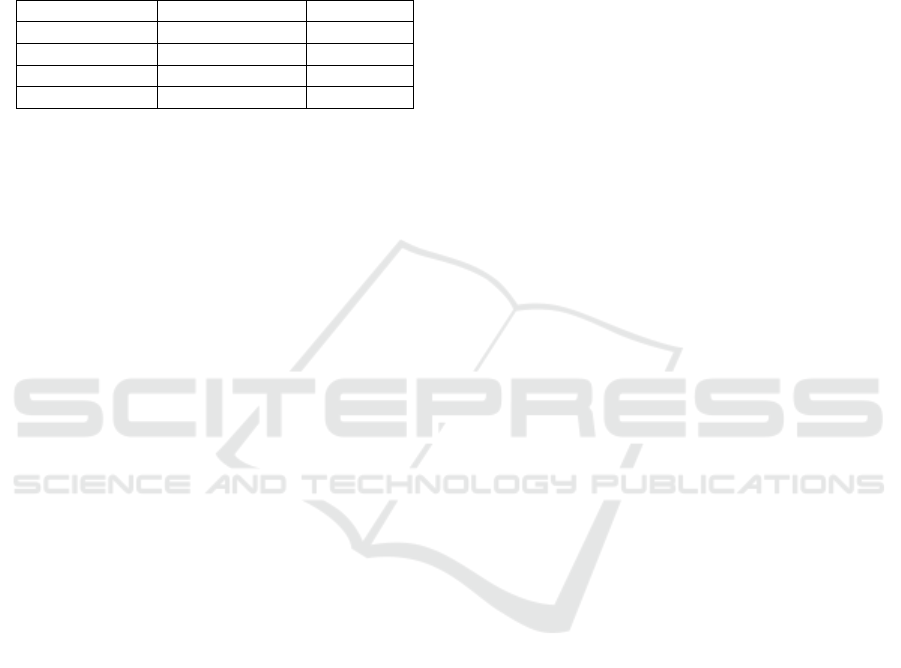

Table 1: Accereditation of Language Study Program.

Study

Programs

Total

Percentage

A

B

C

Arabic

159

16,35

47,80

35,85

Ducth

2

50,00

50,00

0,00

English

493

8,93

62,68

28,40

Japanese

41

21,95

70,73

7,32

Germany

15

46,67

46,67

6,67

Chinese

16

12,50

68,75

18,75

Source: BAN-PT, July 2018

Along with the pace of civilization development,

knowledge and technology, teachers of Arabic and

other foreign languages in Indonesia should be aware

of the rapid development and the use of mobile

phones. Internet user behavior in Indonesia should be

used as study material associated with Arabic

Baso, Y., Padjung, R. and Budi, P.

The Proliferation of Smartphones and their Effects on Improving the Vocabulary of Indonesian Lear ners of Arabic.

DOI: 10.5220/0008681701430147

In Improving Educational Quality Toward International Standard (ICED-QA 2018), pages 143-147

ISBN: 978-989-758-392-6

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

143

learning media. A survey conducted by the

Indonesian Internet Service Providers Association

(APJII) in 2016 and 2017 shows that 132,7 and

143.26 million people are internet users from 257 and

262 million Indonesian population (APJII, 2017).

Penetration of internet users, the devices used and

the browser used is noteworthy as shown in table 2:

Table 2: Devices Used for Browsing.

Devices

Total (million)

Percentage

Smartphone

89,9

68,57

PC

19,5

14,87

Laptop

16,7

12,74

Tablet

5

3,81

Source: APJII, 2016

Based on this data, the writer has not yet obtained the

information on how many teachers use smartphones

and the internet as one of the learning media. This is

one side of the community's potential learning age

and lifestyle using a smartphone. This data is

interesting to study especially the study of Arabic.

Data on smartphone and internet usage in

Indonesia is a challenge for teachers of Arabic at

Hasanuddin University (Unhas). We are challenged

to make it one of the Arabic learning media. We have

to attract the attention of teachers in our institution to

find ways to make this smartphone to be used

efficiently and effectively as one of the learning

media.

This effort is an initiative to attract and improve

the interest of students learning Arabic while facing

the demands and challenges of people living in the

technology era 4.0. The use of cellular technology as

an educational device can no longer be avoided

(Clough et.al., 2008; Sachs and Bull, 2012). Some 4.0

technology features including mobile phones have

provided many benefits in language learning,

including a) portability of smartphone devices that

can be taken to different locations; b) social

interactivity for users of this mobile device who can

collaborate and exchange information with others; c)

context sensitivity that allows mobile phone owners

to use it to collect real data or simulations that are

appropriate to a particular location, environment and

time; d) connectivity that enables users to connect to

data collection devices, other devices, and to network;

and e) individuality for users who can provide

scaffolding for learning tailored to their needs

(Klopfer, 2002). In other words, the comfort,

usefulness, and currentness of this mobile device

allow students to learn the right things at the right

time in the right place Seppälä & Alamäki, 2003;

Peng et.al., 2009)

The writer is constrained by a lack of study or

research that discusses the difficulties of using

smartphones as a medium of learning Arabic. Indeed,

an article was found that discussed the obstacles to

integrating smartphones in learning. The constraints

in question include small screen size, high costs,

speed of access, smartphone intelligence level,

technical difficulties for the owner, and lack of

integration of existing smartphones with e-learning

(Chen-Chung et.al., 2009; Tai & Ting, 2011; Gong &

Wallace, 2012).

Another challenge in using smartphones as

learning supporting media is the impact of this

technology regarding interaction. The interaction

referred to in this article is a reciprocal relationship

that requires at least two objects and two actions.

Interactions occur if objects and events influence each

other (Wagner, 1997). Moore (1989) mentions three

types of interactions are often discussed, namely the

interaction between the instructor and students, the

interaction between students and students and the

interaction between students and teaching material.

The interaction between instructors and students is

intended to strengthen students' understanding of

teaching material including the meaning of the

teaching material Thurmon (2003). The interaction

between instructors and students is the main factor or

key factor in motivating students to learn and

maintain students' interest in learning any material

(Moore, 1989). Moreover, the interaction between

students and students is interpreted as the relationship

between students and students with and or without

instructors (Thurmond, 2003). The study of peer

interaction becomes important especially about the

application test and evaluation of learning material

(Moore, 1989).. The interaction between students and

learning content is the attitude and behavior of

students in understanding teaching material

(Thurmond, 2003).

The writer identifies that there is still less research

or study on the impact of smartphone technology on

interaction (as discussed earlier). That is why this

article is presented to bridge the scarcity in this study.

In connection with this, this study has two

fundamental questions, namely:

1. How do Arabic teachers use a smartphone in

teaching to improve students' Arabic vocabulary

mastery?

2. What challenges were experienced by the

Arabic language teachers and students in doing

the interception through smartphones as a

learning medium?

ICED-QA 2018 - International Conference On Education Development And Quality Assurance

144

2 METHODS

The participants in this study are students of the

Arabic Study Program and who are enrolled in the

academic year 2015 and 2016. Students of 2016

programmed the Arabic Language Proficiency course

and those of 2015 scheduled Translation courses.

Students of 2015 used smartphones as one of the daily

learning media while those of 2016 either they used it

or not. The department has prepared a computer

laboratory that facilitates students’ access to the

Learning Management System (LMS).

In this study, two methods of data collection were

used, namely interviews and analysis of participants

statements uploaded on the LMS discussion forum

menu. Both of these techniques were carried out to

compare the results of the vocabulary memorization

of the participants of these two courses. This

technique is also intended to explore the relationship

or interaction between fellows, between lecturers and

students, and between students and learning

materials.

Data from interviews were analyzed by using a

verbal analysis method (Chi, 1997). Data collected

from interviews, was arranged according to the same

characteristics, ideas, concepts, arguments and

discussion topics. Data that was considered

unnecessary was then removed from the database.

This data was used to see the relationship between

the achievement of students' Arabic vocabulary test

results (quantitative data) and their statements in

interviews (qualitative data). This was done to assist

the writer in interpreting the results of the

participants' vocabulary test and their statements in

the interview.

To enrich the validity of the interpretation of the

interview results, the sharpness of analysis is needed.

To strengthen this argument, of course, we need

quotations for various statements obtained in the

interview. The writer used interview citation

techniques (Merriam, 1998).

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The learning materials for these two subjects were

uploaded on the Unhas LMS. This LMS is prepared

as an official media supporting lectures. All Unhas

students, including this participant, have an account

to log in to at Unhas LMS. Students have access to

download lecture materials, do assignments, work on

closed questions, send in assignments, conduct class

discussions and group discussions both

synchronously and asynchronously.

The writer prepared lecture materials, especially

lists of vocabulary that must be mastered by the

participants of both courses. Regarding the material

for mastering Arabic vocabulary, students of 2015

were directed to optimize smartphones. Lecturers

prepared special applications for daily vocabulary

input. Translation course participants were advised to

upload at least 15 memorized vocabularies per day.

They input this vocabulary through their respective

smartphones.

The list of vocabulary that must be mastered by

the participants was also prepared in an interactive

form. The participants chose the theme of Arabic

vocabulary, for example, vocabulary relating to the

house and its contents, the theme of food, fruit and

vegetables, and so on. Lecturers provided this Arabic

vocabulary test using the Hot Potatoes application

(Baso, 2009).

The evaluation of vocabulary mastery skills

between 2015 and 2016 class participants is different.

In the 2016 class, the vocabulary mastery ability was

tested with oral test through the layout. While in 2015

class participants, it was tested through interactive

test using smartphones. Class participants were

required to input a minimum of 15 Arabic vocabulary

per day.

The lecturer prepared an Arabic vocabulary input

application through Google Application Form. The

vocabulary inputted was the vocabulary memorized

that day. So only the memorized vocabulary was

allowed to be input in this application.

The 2015 class participants also sometimes tested

their vocabulary skills about 15 minutes before the

translation class began. Lecturer displayed pictures or

words in Indonesian followed by choice of Arabic

vocabulary. The participants got unique cards each.

When the questions were displayed on the LCD, the

participant raised and showed his/he unique card.

This unique card was given letters A, B, C, and D on

each side. If a student wanted to answer the letter D

for the question displayed by the lecturer on the LCD,

then the D side of the unique card must be shown

upright. The lecturer then raised his smartphone also

to record the unique card of the lecturers. This

recording was directly stored in the lecturer database

folder.

In this way, it was expected that the participants

would always maintain memorization of their

vocabulary at least 15 words per day. This process

also shows that both 2015 and 2016 class participants

must always access LMS and practice mastering their

Arabic vocabulary. Following this stage, they had to

The Proliferation of Smartphones and their Effects on Improving the Vocabulary of Indonesian Learners of Arabic

145

try to memorize the vocabulary. At this stage, there

are differences between the two academic years. 2016

class tried to memorize the vocabulary and at the

same time prepared to be tested face to face. 2015

class students had to do another stage that was

different from that of 2016 class, which inputted a

minimum of 15 vocabularies memorized per day

through smartphones and prepared to be tested per

week through a unique card and lecturer’s

smartphone.

The answer to the second question consists of two

parts, namely the challenge for the teacher and the

students in 2015 and 2016 classes. For the challenges

of students, the two academic years also experienced

different levels of challenges.

The implementation of learning involving media

in networks and smartphones is related to three main

things, namely brainware, hardware, and software.

Lecturers are a part of brainware of this research. The

writer, as well as lecturer in these two subjects,

experienced several challenges including challenges

in preparing lecture materials which were expected to

improve vocabulary of participants, conduct

interaction processes with, revise vocabulary content

and challenges in conducting tests or evaluating the

achievement of students Arabic vocabulary mastery.

The preparation of teaching materials, especially

Arabic vocabulary training material in an interactive

network drained the energy, time and mind of the

course leader of this subject. Time must be arranged

to adjust with a family schedule where they are

usually ignored to have a sort of recreation and leisure

moments. This schedule must be discussed with

family members and had to be posted on the wall at

home. This schedule was posted so the rest of the

family members understood the schedule and agreed

to it. This schedule would act as the reference in

arranging family leisure time.

Teachers must have extra time, energy and

patience in preparing this course material. They must

be connected to the LMS network all the time. They

must follow the semester learning plan and prepare

exercises to support the improvement of the Arabic

vocabulary of the participants. Uploading this course

material must sometimes be carried out at home. This

is done because the material cannot be completed on

campus because of other schedules that also require

time. This is where the challenge is when the time

provided to prepare this material is insufficient and

collides with family schedules.

The interaction between lecturer and participants

was done in several ways, including through the LMS

discussion forum and smartphone menus. Students

felt more comfortable communicating via

smartphones than through the LMS forum menu. In

response to this, participants were directed to install

telegram social media applications on their

smartphones. The reason is that telegram application

is very light to access, either through smartphones or

laptops. Data is stored either in cloud, text or video

based. Each telegram group was created.

At this stage of interaction, sometimes the

participants sent messages regardless of the time for

example in the morning or midnight. The instructor

of the course has warned them from the beginning of

the class about the times that properly to send

messages. However, because of worries and

anxieties, some participants forget the time

agreement.

Their worries or anxieties are caused by failure to

access the LMS or late inputting memorized

vocabulary per day. This condition made the

participants less concerned about sending messages,

primarily through their telegram. The other side

learned in this condition was that the participants

could learn about when was the proper time to send

messages to their lecturers. This process teaches

many lessons not only to lecturers but also to the

participants or students especially in writing ethics

using correct and proper Indonesian language.

Another challenge was the revision of learning

material and interactive questions on the network and

revision of smartphone-based questions. Often

learning material has been prepared. However,

because there were other references considered better

to support the vocabulary mastery skills of the

participants, it took times to upload the information

on the LMS.

Memorizing achievement of participants (n = 29)

of 2015 class which involves smartphones as the main

media in the learning process is better than the

achievement of Arabic vocabulary memorization of

the participants (n = 31) in 2016 class. The

comparison of the achievement of these two

vocabulary memorization on average (1436: 532

vocabulary).

Other data shows that 62.07% of the 2015

participants had memorized vocabulary above 1750

words for one semester. This achievement has

exceeded the minimum target limit of 1560 words

(one month is only 26 inputting days). On the

contrary, 2016 participants have not achieved the

minimum vocabulary memorization in one semester.

This condition can be seen in the following graph.

The name of the participant was removed to maintain

confidentiality.

The duration of the study was not analyzed. The

study duration might affect the mastery level of

ICED-QA 2018 - International Conference On Education Development And Quality Assurance

146

Arabic vocabulary. 2015 students took more than a

year to study Arabic compared to those of 2016.

However, in the Arabic Language proficiency

courses, there were three students of a previous

academic year who, despite re-taking the subject,

found themselves in the very low level of mastery in

2016 class .

The factor that needs to be observed is the

treatment of the access to LMS between the two

academic years, which was not much different. They

could access learning materials and interactive Arabic

exercises at any time. The only difference was the

frequency of smartphone usage in the memorization

of at least 15 vocabularies per day. As for 2016 class

, it was only recommended to memorize at least 15

words per day, but they were not obliged to input their

memorization every day via a smartphone.

4 CONCLUSION

The use of smartphones as learning media is quite

effective and efficient. The use of smartphones to

improve the ability to master Arabic vocabulary is

sufficient enough as an evidence. The design of the

use of smartphone media is also quite easy for the

instructor in conducting evaluations and tests of

vocabulary mastery skills.

The preparation of interactive training for vocabulary

mastery course materials takes a lot of energy,

tenacity and patience from the lecturers. Teachers

must consider supporting facilities, especially

hardware and software supporting the smooth use of

this media. In addition, the lecturers must also

consider whether or not students afford smartphones.

This article advises educators and instructors to be

keen in addressing the development of current 4.0

technology. The era of disruption can no longer be

avoided. This condition seems to force educators and

teachers to utilize 4.0 technology, including

smartphones.

REFERENCES

APJII, 2017. Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet

Indonesia. [Online]

Available at: https://apjii.or.id/survei2017

[Accessed 15 May 2018].

BAN-PT, 2018. Direktori Hasil Akreditasi Program Studi.

[Online] Available at:

https://banpt.or.id/direktori/prodi/pencarian_prodi

[Accessed 04 Juli 2018].

Baso, Y. S., 2009. Cara Mudah Membuat Latihan Interaktif

Pembelajaran Bahasa. 1 ed. Malang: Mayskat.

Chen-Chung, L., Chen-Wei, C., Nian-Shing, C., & Baw-

Jhiune, L., 2009. Analysis of Peer Interaction in

Learning Activities with Personal Handhelds and

Shared Displays. Journal of Educational Technology &

Society, 12(3), pp. 127-142.

Chi, M., 1997. Quantifying Qualitative Analyses of Verbal

Data: A Practical Guide. The Journal of the Learning

Sciences, 6(3), pp. 271-315.

Clough, G., Jones, A., McAndrew, P., & Scanlon, E., 2008.

Informal Learning with PDAs and Amartphones.

Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24(5), p. 359–

371.

Gong, Z., & Wallace, J., 2012. A Comparative Analysis of

iPad and other M-Learning Technologies: Exploring

Students’ View of Adoption, Potentials, and

Challenges. Journal of Literacy and Technology, 13(1),

pp. 2-29.

Klopfer, E., Squire, K., & Jenkins, H., 2002. Environment

Detectives: PDAs as a Window into a Virtual Simulated

World. Proceedings of IEEE International Workshop

on Wireless and Mobile Technologies in Education, 19

Dec, pp. 95-98.

Merriam, S., 1998. Qualitative research and case study

applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

M.

Moore, M., 1989. Three Types of Interactions. The

American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), pp. 1-7.

Peng, H., Su, Y., Chou, C., & Tsai, C., 2009. Ubiquitous

Knowledge Construction: Mobile Learning Redefined

and a Conceptual Framework. Innovations in Education

and Teaching International, 46(2), pp. 171-183.

Sachs, L., & Bull, P, 2012. Case Study: Using iPad2 for a

Graduate Practicum Course. [Online]

Available at:

https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/40057/

[Accessed 14 June 2018].

Seppälä, P., & Alamäki, H., 2003. Mobile Learning in

Teacher Training. Journal of Computer Assisted,

Volume 19, pp. 330-335.

Tai, Y., & Ting, Y., 2011. Adoption of Mobile Technology

for Language Learning: Teacher Attitudes and

Challenges. The JALT CALL Journal, 7(1), pp. 3-18.

Thurmond, V., 2003. Defining Interaction and Strategies to

Enhance Interactions in Web-based Courses. Nurse

Educator, 28(5), p. 237.

UNESCO, 2012. Mobile Learning for Teachers in Africa

and Middle East: Exploring the Potential of Mobile

Technologies to Support Teachers and Improve

Practice. 2, June ed. Paris: United educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Wagner, E., 1997. Interactivity: From Agents to Outcomes.

New Directions for Teaching and Learning, Volume

71, pp. 19-26.

The Proliferation of Smartphones and their Effects on Improving the Vocabulary of Indonesian Learners of Arabic

147