The Sunset of Gotong Royong in Village of Olak Alen

Dwi Wulandari, Thomas Soseco*, Bagus Shandy Narmaditya, Ni’matul Istiqomah, Nur Anita

Yunikawati, Emma Yunika Puspasari, Agus Sumanto, Magistyo P. Priambodo

Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Malang

Keywords: Gotong Royong, Social System, Rural

Abstract: Social capital is commonly found in villages of Indonesia in the form of gotong-royong. Nowadays,

modernization has potentially reduced the existence of gotong-royong. This research aims to explore the

existing situation of gotong-royong in Village of Olak Alen and investigate causing factors. This research

employed qualitative research. The findings showed that social capital that reflected in the tradition of

gotong-royong in the Village of Olak Alen is currently wiped out from the community.

JEL Classification: P25, O18, O15

1 INTRODUCTION

Social capital has played important role in people’s

activities in Indonesia (Iskandar, 2016). People

activities will be led by social capital which was

commonly known as gotong-royong inherited from

their ancestors. Several studies showed that activities

that led by social capital will play role in gain higher

welfare, for example Dharmawan (2007); Bowen

(1986). Dharmawan (2007) found that farmers

community that intensively interacted with nature

create some collective-based-associational-ties

which functioned as a safety net to farmers’

livelihood. Indigenous livelihood institution, which

represented in associational-ties like patron-client, is

the most important part of social security net in

villages. That net exists for centuries to provide

economic security of households collectively.

One measurement for economic security is

through wealth accumulation. Success households,

in the economic term, will able to accumulate

wealth. Besides higher income earned, households

must able to accumulating assets (whether liquid, for

example bullion and jewelry or non-liquid assets, for

example house and land area). Unfortunately, the

capital accumulation tends to be weakened by losing

of social capital ties. Recent studies show that losing

social capital ties in villages may lowering people

welfare, for example Wetterberg (2004);

Dharmawan (2007); Mavridis (2015).

Wetterberg (2004) found one factor that causes

the losing in social capital ties is less of state

assistance. Dharmawan (2007) also found that

agricultural transformation may result in the

diminishing role of social system and ecology in

villages. Mavridis (2015) found that Indonesian

ethnic diversity increases tolerance but may lower

social capital outcomes, such as trust, perceived

safety, participation in community activities, and

voting in elections. In the Village of Olak Alen,

most of its population work in the agriculture sector.

This economic activity is inherited from their

ancestors, together with various social capital.

Nowadays, the situation is changed. Because of

modernization and previous economic crises

potentially change or even delete social capital in

that village. The change or diminish of social capital

potentially bring numerous consequences, both for

the economic and social condition. Thus, it is

important to reveals how the inexistence of social

capital in one village may change population living

condition. This research is aimed to investigate the

existence of social capital in Village of Olak Alen,

Indonesia and to find how changes in social capital

will affect population welfare.

Wulandari, D., Soseco, T., Narmaditya, B., Istiqomah, N., Yunikawati, N., Puspasari, E., Sumanto, A. and Priambodo, M.

The Sunset of Gotong Royong in Village of Olak Alen.

DOI: 10.5220/0008784101430148

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Research Conference on Economics and Business (IRCEB 2018), pages 143-148

ISBN: 978-989-758-428-2

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

143

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Bowen (1986) constructed social interaction in

Indonesia into koperasi (cooperatives;

constitutionally the basis of the economy),

musyawarah (consensus; technically the basis for

legislative decision making); and, underlying all the

others, gotong royong (mutual assistance). Bowen

(1986) stated that gotong royong as a mutual and

reciprocal assistance, as in the traditional Javanese

village where labor is accomplished through

reciprocal exchange, and villagers are motivated by

a general ethos of selflessness and concern for the

common good.

Bowen (1986) stated that even though the term

gotong royong is generally perceived by Indonesians

to be a long-standing Javanese expression (and this

perception is part of its status as a bearer of

tradition), it is more likely an Indonesian

construction of relatively recent vintage. The root of

the expression is probably the Javanese verb

ngotong (cognate to the Sundanese ngagotong),

meaning "several people carrying something

together," plus the pleasantly rhyming royong.

Although some newer Javanese dictionaries include

royong as a separate lexical item with the same

meaning as gotong he has been unable to find any

Javanese who recognized the word royong by itself.

The nature of reciprocity and collective labor in

gotong royong tradition can be separated into three

forms (Bowen, 1986): labor mobilized as a direct

exchange, generalized reciprocal assistance, and

labor mobilized on the basis of political status.

Firstly, labor exchange, either between individuals

or involving rotating work parties, involves a

calculation of the amount of work to be

accomplished by each participant. Such work

arrangements are particularly common for major

agricultural tasks, notably hoeing, plowing, planting,

and harvesting.

Secondly, generalized reciprocity. The second

type of mutual assistance is based on an idea of

generalized reciprocity. The villager, by virtue of his

or her status as a member of a community, is obliged

to help out in events such as the raising of the roof

of a house, the marriage of a child, or the death of a

relative. Generalized reciprocity involves both a

general obligation and the idea of an eventual return.

The result is that within a particular circle of kin or

neighbors one feels a general obligation to help, but

one also remembers how much the needy person

helped in the past.

Thirdly, the mutual assistance that is nationally

called gotong royong consists of labor that is

mobilized on the basis of political status or

subordination. Such labor appears as "assistance"

when it is contributed, for example, toward the

repair of an irrigation system, but it begins to

resemble corvee when it is commandeered by a local

official for the construction of a district road.

Rural welfare can be influenced by accessibility

(Soseco, 2016). He found that better accessibility

leads to better income earned by villagers. Income

inequality also plays role in affecting rural welfare

(Soseco, et al., 2017). They found that rural welfare,

indicated from their ability to obtain a house, is

influenced by the existence of income inequality.

Moreover, rural welfare can be affected by savings

accumulation (Singh, 2011). Savings are the

unconsummated earning of individual consumption

and capital formation including investment (Singh,

2011). National savings constitutes the sum of net

changes in the net worth of all economic units in an

economy. With many financial sources and given

assets, in addition their own income, new families

should be easier to accumulate wealth. However,

this does not exist in our study area. Most of the new

families still live in persistent level.

Singh (2011) stated that majority of people living

in rural and semi-urban parts of India lack

knowledge of the financial markets and fail to

understand them. Gold, either in primary or in

jewelry form, still remain the second most preferred

option among the Indian public after deposits in the

banks. Rural households saved their income in both

monetized as well as non-monetized forms.

Moreover, some of the monetized savings are held in

financial assets of the informal rural financial market

can be considered as potentially mobilizable by the

financial agencies.

In rural areas, savings and investment are

influenced by occupation, expenditure, assets, and

saving. While the number of dependents, age

composition, nature of work, and education level did

not have a significant effect on saving (Odoemenem,

2013). Some important factors that influencing

investment pattern based on Kalidoss and

Jenmarakkini (2012) are monthly income, monthly

expenditure, family size, monthly savings, the

reason of savings, the source of savings, and source

of information.

IRCEB 2018 - 2nd INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH CONFERENCE ON ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS 2018

144

3 METHOD

This study applied qualitative research. Three

informants are involved in this research. All of them

are male, working in the agriculture sector, and have

a relatively same socio-economic status. Also, we

employ supporting data from related institutions

such as the Indonesian Statistics Bureau and Local

Government and local government. The study area is

in the village of Olak Alen, Regency of Blitar,

Province of Jawa Timur, Indonesia. this village is

situated on main roads connecting two big cities in

Jawa Timur, Malang and Blitar. This village is not

far from two tourism objects (Karangkates Dam and

Lahor Dam). Those spots are originally coming from

a hydroelectric power plant which later developed as

tourism objects.

We asked three villagers to participate in our

research. All of our respondents are male, with the

age between 30-40 years old. All of them are have

senior high school (year 16-18) as their highest

educational attainment. In their families, both of

parents are workers. Husband work in farmland,

while their wives help them in farmland.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Our focus area is based on rural typology from Lowe

and Ward (2009). Their simplified typology can be

seen in table 1.

Table 1: Rural Area Types Generated by the Cluster

Analysis

No

.

Type

Description

1.

Dynamic

commuter

areas

Socially and economically

dynamic and affluent

2.

Settled

commuter

areas

Share characteristics with the

first type, but tend to be less

vibrant, more settled and more

provincial, often associated

with other city regions,

commuter hinterlands of

regional hubs,

3.

Dynamic

rural areas

Have a high density of

professional and knowledge

workers, sometimes being

associated with universities or

other research centers.

4.

Deep rural

areas

The countryside that still

dependent on farming but with

increasingly important tourism

element and less reliance on

commuting. Sparsely

populated farming

communities.

5.

Retirement

retreat

areas

Comprise popular retirement

destinations and have ageing

populations.

6.

Peripheral

amenity

areas

Located in economically

marginal zones, particularly on

the coast, that may have

suffered structural economic

decline and are now propped

up by tourism or retirement-

related services.

7.

Transient

rural areas

Situated close to struggling

urban centres, associated with

commuting, but also

associated with low incomes.

Near to declining market

towns, former mining areas,

etc.

Source: Lowe and Ward (2009); Gallent and Robinson

(2012)

Based on table 1, Village of Olak-Alen is

considered as ‘deep rural areas’. Lowe and Ward

(2009) explained deep rural areas below:

Deep rural areas would resonate most closely

with popular perceptions of the ‘traditional’

countryside. Conventional livestock farming is more

prominent, together with rural tourism. Population

density is way below the rural mean, creating a

pervading sense of tranquility. In other respects,

though, Deep Rural areas seem to lack sufficient

symbolic resources to attract in those socio-

economic classes that are underpinning the vibrancy

of the ‘commuter’ categories. Population change is

only at the rural average, there being neither

significant in-migration nor much commuting.

Physical remoteness and poor infrastructure (for

example, of information and communication

technology networks or motorways) explain some of

the situations.

In Olak Alen, most of its population work in the

agriculture sector. Majority of them plant paddy and

corn, These commodities are different in the suitable

season to be planted. In rainy seasons, farmers plant

paddy, while in dry seasons they plant corn. Besides,

they also have cattle in their yard. Commonly, they

have cows, chickens, or ducks. This activity is

needed to support households’ finance. Our

respondents said that majority of farmers in the

Village of Olak Alen are depended on their harvest.

They get a fluctuactive earning. By depend on crop,

they get a periodical earning, usually 3 or 4 months.

Thus, to overcome the financial problem, most

farmers has cattle in their backyards. Also, while

waiting for harvesting period, some of them work in

The Sunset of Gotong Royong in Village of Olak Alen

145

non-agricultural sectors such as drivers, construction

workers, or pedicab drivers.

In the past, the atmosphere in the Village of Olak

Alen is full of local wisdom gotong-royong

(working together to solve one problem). This action

does not only exist in social aspect but also in

economic aspect. In social aspect, gotong-royong is

intended to solve one or more social problems. For

example, lack of infrastructure (e.g. poor road

condition or irrigation system) is solved by working

together to overcome the problem. The participants

work with no payment. Furthermore, some families

voluntarily provide food and drinks for them. In the

economic sector, gotong-royong is conducted to

overcome some economic problems. People who

need additional labor usually ask their neighborhood

to help them, usually with no or little gratification.

To pay the labor cost, the employee also conducts

reciprocal action in other farmlands.

In our field visit in the Village of Olak Alen, the

tradition of gotong-royong is partially swiped out

from villagers’ tradition. Gotong royong still exist

only to overcome social problems, whereas in to

solve economic problems, people tend to use the

capitalist method, i.e. by pay the workers. The

inexistence of gotong-royong to overcome economic

problems in Village of Olak Alen is started from

1997-1998, where the economic crisis peaked in

Indonesia. This situation worsened people welfare.

Thus, they tend to avoid work voluntarily but work

by salary. On the other hand, the crisis boost created

additional unemployment. They, who are

unemployed, would work any jobs with any level of

salary. This moment created the tradition of paid-

workers in all economic aspects. Gotong royong still

exist in solving social problems. After a period of

1997-1998, the cultural ties are weakened by the

financial crisis. It allowed people to move to another

village. Also, it drove to higher mobilization among

people. Thus, villagers seemed to give a big effort to

preserve their ancient tradition through gotong-

royong in solving social problems.

There are several causes of diminishing spirit of

gotong-royong in Village of Olak Alen. First, people

tend to place money as their first priority. This

mindset drives people to find other financial sources.

For example, people who feel that their income is

not sufficient to pay their needs will find side jobs or

work in other cities. Their insufficient income also

leads to a poor condition where almost all aspects in

life are measured in money.

Second, people will feel that their neighborhood

as competitors, not a partner. This situation drives to

unacceptable ways conducted by some farmers to

increase their production. In the Village of Olak

Alen, there is a kelompok tani (a group of farmers)

who accommodates them in agriculture issues. This

kelompok tani is aimed to provide inexpensive

seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. Also, kelompok

tani is used to introduce better farming methods and

cures. Insufficient income drive to some farmers

cheats by approaching the leaders of kelompok tani

to gain privilege. As a result, only they who have an

exclusive connection to kelompok tani can access for

inexpensive seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. Other

farmers will lose the opportunity to gain those

inexpensive items.

Third, the income inequality in the Village of

Olak Alen created additional pressure on poorest

people. Rich families have bigger opportunity to

enhance their living standard through many

channels, e.g. gain wider access to the market,

bigger capital to operate their farmlands, and apply

new farming techniques. On the other hands, poorer

families tend to stuck in their living condition. To

solve their financial problems, some families sell

their farmland to richer families. The peasant lives in

poor condition and will to work at any wage level.

Fourth, there are differences in investment

pattern among a different group of farmers. Richer

families will have the capacity to invest in some

investment instruments. Majority of them buy

jewelry and land area as their investment tools.

Jewelry is easily bought and sold, even in their

nearest jewelry stores in their village. Besides, land

area is usually sold at a low price by poorer families

to fulfill their needs. They, especially who are

trapped in debt, sell their farmland at a low price to

get fresh money. In contrary, poorer families will

have no adequate investment. Their low income is

only sufficient to pay their daily needs.

Fifth, an agricultural transformation that provides

benefit only for a few people. Our respondents stated

that their living condition is lower than before the

1997/1998 crisis. They argued that it is difficult to

find high income nowadays. They have to struggle

with their relatively constant earnings from their

farmland. Otherwise, they must find other jobs or

move to other cities. In the previous period, people

feel safe and easy to gain income. Everything is

considered guaranteed by the government. Obtaining

money has not a big concern for them. Thus, people

enjoy sharing their time and force for their

community, which was called gotong-royong. In that

era, gotong-royong was conducted in almost all

aspects of community: social, economic, religious,

etc. As a result, nowadays, people who do not enjoy

IRCEB 2018 - 2nd INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH CONFERENCE ON ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS 2018

146

Livelihood Base in

Agricultural Sectors

Livelihood Base in Non-

agricultural Sectors

Capital and Human Capital

Capital and Human Capital

Extensification,

Intensification,

Farm-worker,

Share-

cropping, Child

Labor, Female

Worker

Livelihood

Strategy

Informal Sector,

Small and Medium

Trading, Rural

Industry,

Agricultural

Product Industry,

Craft Livelihood

Strategy

Migratio

n and

Multi-

Liveliho

od

Strategy

the progress of modernization will distract

themselves from the social system.

The sunset of local wisdom, reflected in gotong-

royong, is also described by Dharmawan (2007). He

found that agricultural reformation in Java Island

destructed existing social system and ecology in

villages. Not only that, agricultural transformation

gave some implications: (1) poor inequality of

agricultural resources and (2) the diminishing of

traditional income sources and at the same time

there were new non-agricultural income sources,

which unfortunately, those new income sources

could not guarantee an increase of welfare of poor

people. In the end, Dharmawan (2007) stated that

the agricultural transformation could end in (1)

higher degree of livelihood insecurity and (2) the

inability for institutional tools to provide sufficient

income for the population.

In Olak Alen, there is a shift of livelihood

sources from agriculture to non-agriculture sectors.

This situation is similar to Bogor Stream that

initiated by Sajogjo (Dharmawan, 2007). This

stream is distinctively different from Western

Stream (commonly from experts from Institute of

Development Studies, Sussex, UK) e.g. Chambers

and Conway, de Haan, Scoones, Bebbington and

Batterbury, and Ellis. The idea of Bogor Stream

emphasizes on the assumption of the work of two

economic sectors, which reflected in figure 1.

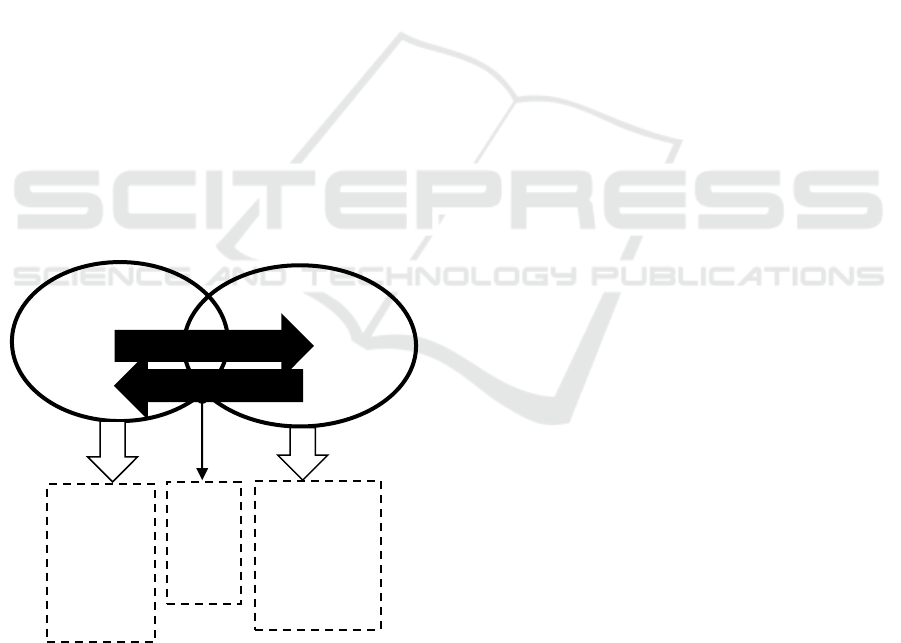

Figure 1: Rural Capital and Human Capital Mobilization

in Two Livelihood Bases based on Bogor Stream.

Source: Dharmawan (2007)

In figure 1, income sources in rural areas are

from agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. Then

the livelihood strategy has developed the work of

two economic sectors (agricultural and non-

agricultural) and also influenced by local socio-

cultural pattern or tradition. There are three elements

which significantly influence the pattern of

livelihood strategy in rural areas: (1) Social

infrastructure, which includes institution and social

norm settings, (2) Social structure, which includes

social layers, agricultural structure, demographic

structure, local ecosystem exploitation pattern, local

knowledge and (3) Social supra-structure, which

include ideology, moral-ethics economic, and value

system.

The existence of two livelihood bases in the

village (agricultural and non-agricultural sectors)

create community involvement into those two

sectors. This can be seen from activities conducted

by each social class in the village. Each people can

use hard capital (land, finance, and physical tools)

and also soft capital (intelligence, skill) to create

some livelihood strategies. The combination of hard

capital and soft capital is majorly influenced by the

previous three socio-culture elements that exist in

the village.

Dharmawan (2007) found that every social

relationship among the population in a village not

only have a neutral connotation but also create an

asymmetrical relationship (and also power). This

relationship always benefits one party only. Most

small farmers are trapped in this relationship.

Majorly, they trapped because of livelihood net that

“push” them and at the same time allow them to

“breathe” especially in the crisis period. This

situation makes a condition where pengijon and

rentenir (loan-shark) freely operates in a village.

Even though farmers realize that they have to pay

very high-interest rate from loan received from

rentenir and pengijon give the low price of their

harvest but they feel that costs rose from pengijon

and rentenir cannot substitute “safe feeling” for

farmers.

The agricultural transformation is responded

differently by the social system in a village. They

who cannot adapt to structural change will force the

community to live in poor condition, in financial and

economic aspects. This situation provides very

limited income sources for them. Sometimes, that

sources cannot provide adequate income for them.

Thus, farmers will retract themselves from an

existing social system in a village. In reality, this can

be seen from the fade of gotong-royong.

Many agenda can be scheduled to provide

sustainable social system, including gotong-royong

(Dharmawan, 2007): (1) there is an urgency to

provide livelihood system and livelihood-oriented

The Sunset of Gotong Royong in Village of Olak Alen

147

community development, (2) it is important to create

rural social-safety net, and (3) it is important to

stipulate rural livelihood access and rights.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Social capital, that reflected in the tradition of

gotong-royong in the Village of Olak Alen is

currently wiped out from the community. Gotong

royong is only implemented in solving many social

problems, not in economic ones. Villagers conduct

various economic activities through wage-earnings

practices. This fade of gotong-royong is caused by

several factors: Firstly, people tend to put money as

their first priority. Secondly, the shift of people’s

role from partners to competitors. Thirdly, income

inequality that multiplies the negative effects.

Fourthly, differences in investment pattern among

different groups of farmers. Fifthly, an agricultural

transformation that benefits only a few people. This

situation creates many people who cannot adapt to

changes will be kicked out from the community.

They will withdraw themselves from the social

system. Many agenda can be scheduled to provide

sustainable social system, including gotong-royong

(Dharmawan, 2007): (1) there is an urgency to

provide livelihood system and livelihood-oriented

community development, (2) it is important to

create rural social-safety net, and (3) it is important

to stipulate rural livelihood access and rights.

REFERENCES

Bowen, J.R. (1986) On the Political Construction of

Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia. The Journal of

Asian Studies, 45(3), 545-561.

Dharmawan, A.H. (2007) Sistem Penghidupan dan Nafkah

Pedesaan: Pandangan Sosiologi Nafkah (Livelihood

Sociology) Mazhab Barat dan Mazhab Bogor. Jurnal

Transdisiplin Sosiologi, Komunikasi, dan Ekonologi

Manusia, 1(2), 169-192.

Gallent, N., and S. Robinson. (2012). Neighbourhood

Planning: Communities, Networks and Governance.

Bristol: Policy Press

Iskandar, M.D. (2016) Social Capital: A Perspective on

Indonesian Society. Retrieved from http://i-

4.or.id/social -capital-a-perspective-on-indonesian-

society/.

Kallidos, K., and Jenmarakkini, E. (2012). A Study on The

Investment Pattern of Rural Investors with Special

Reference to Nagapattinam District. International

Journal of Management Focus, 2(3), 1-4.

Lowe, P., and Ward, N. (2009). England’s Rural Futures:

A Socio-Geographical Approach to Scenarios Analysis,

Regional Studies, 43(10), 1319-1332.

Mavridis, D. (2015). Ethnic Diversity and Social Capital

in Indonesia. World Development. 67,376-395.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.028

Odoemenem, I.U., Ezihe, J.A.C., and Akerele, S.O.

(2013). Saving and Investment Pattern of Small-Scale

Farmers of Benue State, Nigeria. Global Journal of

Human Social Science Sociology and Culture, 13(1), 6-

12.

Singh, E. N. (2011). Rural Savings and its Investment in

Manipur (A Case Study of Formal Finance vis-a-vis

Marups). Management Convergence, 2(2), 10-30.

Soseco, T. (2016). The Relationship between Rural

Accessibility and Development. Jurnal Ekonomi dan

Studi Pembangunan, 8(2), 31-40.

Soseco, T., Sumanto, A., Soesilo, Y.H., Mardono, Wafa,

A.A., Istiqomah, N., Yunikawati, N.A., and Puspasari,

E.Y. (2017). Income Inequality and Access of Housing.

International Journal of Economic Research, 14(5).

Wetterberg, A. (2004). Crisis, Social Ties, and Household

Welfare: Testing Social Capital Theory with Evidence

from Indonesia. Working Paper 34223. New York:

World Bank.

IRCEB 2018 - 2nd INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH CONFERENCE ON ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS 2018

148