The Impact of Mobile Devices

on Indonesian Men’s Sexual Communication

Dédé Oetomo

1

, Tom Boellstorff

2

, Kandi Aryani Suwito

3

and Khanis Suvianita

4

1

GAYa NUSANTARA Foundation, Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Department of Anthropology, University of California Irvine, USA

3

Communication Department, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

4

Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies, UniversitasGadjahMada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: sexuality, identity, gay, men who have sex with men, mobile devices, social media

Abstract: This paper aims to explore the impact of mobile devices on Indonesian men’s sexual communication. Gay

men need to express their homosexual feelings despite resistance from society. The paper is based on

qualitative and quantitative research used to describe and assess the current use of social media in Indonesia,

paying specific attention to how it is transforming sexual negotiations among gay men and other MSM. Its

objective is to gain an understanding of how online social interactions are transforming gay and MSM

Indonesians’ experience of sexuality, identity and community. The findings demonstrate how the

participants are very committed to social media as shown by the degree of openness in declaring their sexual

orientation. Specifically, this research discovered that social media is used mostly by youths to find partners

and to connect to other gay men as a means to construct a sense of community and belonging. Interestingly,

one of the results also revealed the favourable reception of gay men toward women when it comes to sexual

relations.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the fourth most populous nation (after China,

India, and the United States), it is unsurprising that

Indonesian has a sizeable percentage of social media

users. Nevertheless, the data on Indonesia is almost

absent from the existing literature. The research

reported here employed qualitative and quantitative

methods to describe and assess the current use of

social media in Indonesia, paying specific attention

to how it is transforming sexual negotiations among

gay men, other men who have sex with men (MSM),

and warias (trans women). The aim is to gain an

understanding of how online social interactions are

transforming gay and MSM Indonesians’

experiences of sexuality, identity, and community.

The research was conducted primarily using surveys

and interviews.

The researchers based in the city of Surabaya

(East Java Province) explored how gay, MSM, and

waria Indonesians use social media to negotiate their

sexual encounters, experiences, identities, and

communities. The research included a survey of the

types of devices, apps, and other social media used.

Online and offline surveys were used to explore how

internet-mediated forms of communication are used

in everyday interactions, and their consequences

related to their understanding of selfhood, sexuality,

and community.

Most of our understandings and theories of the

internet are based on data from the United States,

Europe, and East Asia (Japan, China, and South

Korea). Given Indonesia’s size and importance, this

research not only gives us a better understanding of

contemporary social transformations in the

archipelago, but it also gives us a more

comprehensive and robust understanding of how the

internet can influence social relations worldwide,

and how these influences are reworked in specific

local contexts. Given that the HIV/AIDS epidemic

remains a serious concern in Indonesia, with

infection rates among gay, MSM, and waria

Indonesians ranging from 15% to over 50%, another

primary outcome of this research is insights for use

Oetomo, D., Boellstorff, T., Suwito, K. and Suvianita, K.

The Impact of Mobile Devices on Indonesian Men’s Sexual Communication.

DOI: 10.5220/0008818501670172

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs (ICoCSPA 2018), pages 167-172

ISBN: 978-989-758-393-3

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

167

related to improved HIV prevention interventions

that effectively make use of online technologies.

2 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The over-arching research questions that guide this

research as listed below:

How are sexual transactions for gay men,

MSM, and warias taking place via online

cultures?

How are forms of male sex work being

transformed via online cultures?

How are gay men, MSM, and waria online

cultures shaped by differences in age,

ethnicity, class, profession, and religion?

How are the norms of sexuality, friendship,

and romance among gay men, MSM, and

waria being transformed by online cultures?

(For convenience’s sake, in the discussion that

follows, we use the phrase “online cultures” to refer

broadly to social interactions online via devices like

laptops, tablets, and smartphones, via apps,

programs, and websites and via social networking

sites (like Facebook) and SMS services (like Twitter

and WhatsApp).

3 RESEARCH METHODS

The research was designed as a community-based

research since it made use of the established

connections in Surabaya’s gay, MSM and waria

communities maintained by the GAYa

NUSANTARA (GN) Foundation over the years.

While Boellstorff and Oetomo are academics,

they have also been close to community work. The

other co-author, Suvianita, also straddles the

academic and community worlds as an ally and

counsellor to people from the community. Suwito is

the only one that is purely academic.

The ideas for the research design, methods and

techniques were work-shopped with core activists of

GN and other academics and graduate students who

are close to the communities in August 2015.

Brainstorming sessions were organised to come up

with possible issues to research. The rest of 2015

saw the team developing the issues further,

continually checking with the realities in the

communities that the GN activists know very well.

By April 2016, a final draft survey questionnaire

was discussed and tried out on GN volunteers and

community members. This year happened to be one

where moral panic type statements from politicians,

social and religious leaders were bombarding the

“LGBT” communities, so we added a few questions

to see how life in online cultures (and offline

cultures) may have changed.

In September to October 2016, the survey

questionnaire was uploaded onto SurveyMonkey,

and its link was announced in all of GN’s social

media channels. 151 fully answered questionnaires

were obtained. In November 2016, the research team

decided to also conduct an offline survey using the

questionnaire. 50 additional respondents were

obtained.

The research team held a workshop in early 2017

to analyse the answers to the questionnaire. Some of

this analysis forms the basis of the following

findings.

4 FINDINGS

4.1 Gender and Sexuality: Identity,

Relationships and Religious

Significance

Sexual identity as perceived by the respondents is

not a stable category with distinctive qualities. In

contrast, most of the respondents believe that

identities are always multifaceted as they are

constructed as a compound selfhood where different

features such as individual preferences, social

background and personal beliefs are reworked and

performed at once in each human being. Given with

four clear options, the vast majority of respondents

chose the label ‘gay’ by 68.85%, whereas less than a

fifth (19.12%) opted for ‘men who have sex with

men’ (MSM). This means that the respondents did

not automatically identify their sexual orientation as

simply being gay, seeing that there are other

alternatives selected, even though by only a few,

such as under the label of ‘bisexual’ (22.79%).

Even though this range of identities seems

sufficient enough to capture the variety in the

sexuality of a gay person, there were diverse

answers provided by the respondents when they

were offered the opportunity to present any response

in addition to the available choices. Surprisingly,

there were 11 different answers written in the

respondents’ own words which were: 1) Gay who

still loves and wants to get married to a woman, 2)

LSW, 3) Pansexual, 4) Bi-curious, 5) Asexual, 6)

Pro-LGBT, 7) Straight, 8) Lesbian, 9) Women who

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

168

like men, 10) Normal, and 11) Individuals who like

masculine men. Some words are quite familiar and

are common terms used when defining one’s sexual

orientation but several descriptions are a very unique

way to reveal an otherwise undetermined label for

specific sexual attraction and experiences.

This result clarifies what du Gay and Hall (1996)

have said in that the term identity is not a natural in

itself, but a constructed form of closure and that

identity naming, even if silenced and unspoken, is an

act of power. A community is a social unit that

stabilises the deep-rooted identity classification with

the play of differences as the only point of origin.

Identity is a cultural site where particular discourses

and practices are entwined and shattered at the same.

The historical route taken by LGBT Indonesians

shows that the homosexual identity first emerged in

urban centre in the early twentieth century. Before

then, it was preceded by the LGBT movement in the

late 1960s when waria, transgender women, came

into view (UNDP, 2014). Considering the fact that

homosexuality is a predominantly Western

discourse, LGBT Indonesians have persisted in order

to secure their local and cultural distinctiveness as a

means to acknowledge how sexuality is highly inter-

related with race, ethnicity, class and other aspects

of identity. The term ‘waria’ as an Indonesian

specific phenomenon demonstrates how language

shapes reality. Boellstorff (2005) refers to male-to-

female transvestites (best known by the term banci)

as waria, which he used to name both female (she)

and male (he). This means that biological foundation

for sexuality is misleading because it is and through

language that one’s subjectivity is produced across

historical and cultural contexts.

Amongst all options, waria scores zero, which

means that none of the respondents associated

themselves with the characteristics of waria as a

specific gender identity. They used another way to

describe their identities which can be put into one of

the 11 categories above. Since almost all of the

respondents are male (92.65%), it is easily

understood that sexual orientation represents the

interests of those who call themselves male. It

explains why only a minority stated ‘bi-curious’,

‘lesbian’, and ‘individuals who like masculine men’

which is language used to represents women’s

discourse on sexuality. However, the sexual identity

of the respondents who says ‘pro-LGBT’ is hard to

properly know as they could only be showing their

support for LGBT individuals who are still

experiencing discrimination and repressive acts

physically, psychologically and verbally. Although

the numbers are very small, its significance brings a

great magnitude to the campaign for the human

rights of LGBT people in the public sphere and

throughout social media.

However, only 80.88% of respondents admit that

they had sex with men while only 19.12% say the

opposite. The number is greater than the 68.85%

respondents who confess that they are gay with a

12.03% difference in percentage. This means that

diversity in sexual orientation is becoming more

extensive, which breaks the long-established

perception that sexual intercourse between men must

be labelled ‘gay’ which leaves no room for other

sexual expressions. This explains the prior outcome

that highlights the variety of sexual identity as

proposed by respondents. The argument that can be

brought to light for this observable fact has been

explained by Hall (1996), who said that difference

matters because it is essential to meaning, and

without it, meaning could not exist. The wide range

of identities breaks not only the existed binary

opposition that separates feminine from masculine in

extreme poles, but also defies the

‘heteronormativity’ as being the ideological force

that works behind all prejudices and violent acts

against LGBT people who stands for the right to be

different. It also dismantles the belief that sexual

subjects should fall into one distinct category and

cannot transgress the boundary without being

marked as deviant, dissonant, disturbing and above

all, subversive.

In spite of the LGBT people’s will to challenge

the traditional norms that marginalise and put them

in an already heterosexual relationship of

subordination, they cannot escape from a discursive

mechanism that requires them to have a ‘husband

and wife relationship’ as a means of survival. It

means that those who are married (13.11%) are not

committed to a monogamous relationship but have

an open relationship. It appears that a sense of

freedom that liberates them from the cultural

expectation to be ‘normal’ conflicts with the need to

express their homosexuality. It affects how the

respondent will decide on their sexual openness to

others and how it brings significance to them.

The degree of sexual openness as illustrated in

the diagram below exemplifies identity as a source

of worry rather than as a place of belonging. Even

though quite a lot of the respondents do not hesitate

to declare their sexuality, there are still considerable

number of people who show reluctance in revealing

their sexual identities for the reason that LGBT are

believed to be a type of illness and taboo for

Indonesian society. The figure confirms that the

community has silenced LGBT people and made

The Impact of Mobile Devices on Indonesian Men’s Sexual Communication

169

their sexuality a secret. There were 18.18% of

respondents hiding their sexuality from view which

again strengthens the idea that acceptance is really a

luxury. Butler (1995; p.29) argues that transgender

and transsexual persons and other LGBT identities

make us not only question what is real and what

must be, but they also show us how the norms that

govern contemporary notions of reality can be

questioned and how new modes of reality can

become instituted. She ensures that gender and

sexual affirmation should be the defining features of

the social world in its very intelligibility.

It needs to be rethought how the concepts such as

‘coming out’ and ‘liberation’, which are very

Western in orientation, should take the local society

into account in view of the fact people are marching

against homosexuality in Indonesia. The Pew

Research Global Attitudes Project reported on

attitudes towards homosexuality and their report

showed that 93% of those surveyed in the country

reject homosexuality and only 3% accept it. Cultural

assumptions on LGBT people are mostly influenced

by the dominant discourse in Indonesian society

which is religion. Contemporary discourse holds that

LGBT sexuality and religion are incompatible, thus

LGBT individuals participate less in religion than

heterosexuals, which has led to a process of

abandonment and being abandoned by their religious

traditions (Henrickson, 2007).

While the vast majority of respondents hold as

having the traditional religion of Islam as the

dominant religious group (56.62%), amongst

Christians (8.82%), Catholics (10.29%), Konghucu

(0.74%), Buddhists (2.94%), and Hindus (0.74%), it

can be perceived that a number of respondents

decided on being Agnostic (11.76%) or Atheist

(6.62%). Atheism, in the broadest sense, refers to the

absence of belief in God(s) by looking for the

answer to the question of meaning in ethical and

philosophical viewpoints. Agnosticism, strictly

speaking, is a doctrine that states that humans cannot

know the existence of anything beyond the

phenomenon of their experience. The scepticism

about religious questions in general and the rejection

of traditional Christian beliefs under modern

scientific thought has so much to do with the notion

of knowing. LGBT people have been objectified and

treated as the object of knowledge by the masculine

hegemony and the heterosexist power. Communities

commonly led by religious conservative clerics that

internalise homophobia and transphobia makes

LGBT people who live in that surrounding find it

hard to fully accept their own sexual orientation and

gender identities (UNDP, 2014). At the same time,

the act of uttering an oppressive view toward LGBT

people in public has created a sense of social

separation. However, there is also a growing

movement among progressive religious leaders and

believers with the relentless endeavour to offer an

alternative reading of the holy text.

4.2 Being Online: Negotiating Sexuality

and Performing Identity

Urban areas with visible gay and lesbian

communities provide expanded opportunities to

meet potential partners. In addition, the internet has

rapidly become a way for gay men and lesbians to

meet one another. There is some evidence that

lesbians and gay men, like their heterosexual

counterparts, rely on fairly conventional scripts

when they go on dates with a new partner

(Klinkenberg & Rose, 1994). This is proven by the

diagram below, which shows that gay men are very

keen to make use of online media for their social

life. There are a considerable number of respondents

who find their life-partner online (74.47%) as

opposed to others who are still looking for

companion in a more traditional way (23.53%).

Specifically, the furthest chart distinguishes a life-

partner from a sex-partner, wherein the results show

that 75% of respondents were looking for a sex-

partner online.

Figure 1: Are you also looking for sexual partners online?

Some scholars have heralded the emergence of

‘the global gay,’ the apparent internationalisation of

a certain form of social and cultural identity based

upon homosexuality. This “expansion of an existing

Western category” is seen to be the result of what

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

170

Altman calls ’sexual imperialism’, which is the

reshaping of local understandings of homo-

sexuality, largely influenced by the development of

global media systems and increasing popular access

to so-called new media (from mobile-phones to the

internet), in order to align them with Western

conceptions of what it means to be gay or lesbian

(Barry, Martin, Yue, 2003). Almost all respondents

use a smart-phone regularly with a reading of

95.08%, followed by laptops and tablets by 72.95%

and 32.79% respectively

For those who use their gadgets to do online

activities, there is an evenly balanced proportion

amongst respondents that go online for 2-4 hours

(30%), 5-7 hours (23.33%), 8-10 hours (22.50%)

and more than 10 hours (20%) in a day. There are

only 4.17% of respondents who said that they

accessed the internet for less than an hour a day.

This upshot is not unexpected, knowing that the

internet which came to Indonesia during the early

phase of the political crisis in the 1990s has risen

both economically and politically to become an

alternative medium that has found its way out of the

control of the state (Hill and Sen, 2000; Lim 2002).

Even if this medium was initially deemed as elitist

due to the unequal access especially amongst the

marginal groups, the impacts are believed and

forecast to increase in the forthcoming years,

considering the advancement of technology in

complying with the most fundamental needs of

individuals as a part of society, which is about being

connected.

Figure 2: On average, how many hours per day you spend

online?

The social space where the access was made is

also vital to analyse since it demonstrates the social

dynamics that occur in gay communities. It is

worthy noticing that building an intimate

relationship, for gay people, can be very problematic

because visibility leads to consequences that can

potentially put gay people at risk. They are

frequently harassed or intimidated and moved on by

security forces that do not hesitate to do violence

when they appear publicly and hang out to find a

sex-partner. Having said this, it is comprehensible

that respondents mostly retrieve a website page or

their social media account on their leisure time,

especially when they are having a walk with their

family (48.84%) and friends (41.86%). The number

of people that access the internet at home is the

lowest, with 18.60% with the difference of 18.61%

from the quantity of those who log on to the internet

at their office.

This end result suggests that the respondents are

comfortable seeking a sex-partner while they are in a

public space as long as they do not have to be

noticeable physically. The timeline does matter for

61.63% of respondents, but does not make any

difference for the rest.

Figure 3: Since what age have you started to look for

sexual partner online?

The most visited social media platforms are

Grindr, Facebook and Blued, which are believed to

be advantageous for the respondents to get a

preferable sexual experience. They start to seek out a

sexual partner at the age of 17-25 with the most

notable figure of 70.93%. This number is followed

by the category of 26-35 years old (16.28%), under

17 years old (8.14%) and over 36 years old (4.65%).

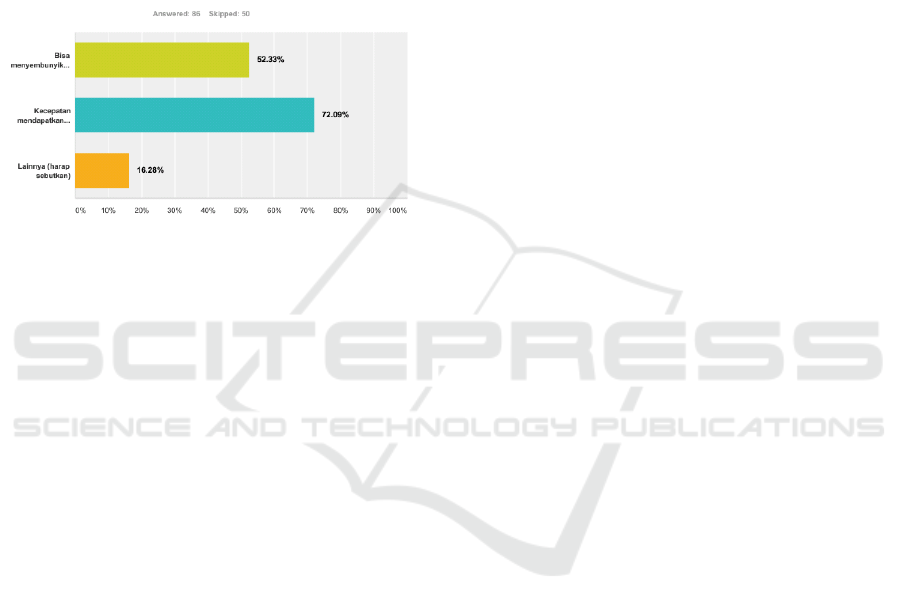

In terms of ease, the majority (72.09%) agree

that social media is the best medium to use to find a

The Impact of Mobile Devices on Indonesian Men’s Sexual Communication

171

sex-partner instantly and 52.33% of respondents

think that the idea of staying hidden and being

unseen is a critical point for them. There were

16.28% persons surveyed who have other answers to

offer. Some says that they can identify people

nearby that are suitable either as a sex-partner or as a

companion. They can also be certain that the

intended persons have the same sexual orientation.

The adequate information can also be collected from

the online account before they actually get involved

with other social media users.

Figure 3: What kind of conveniences that you get from

using online media in looking for sexual partners?

5 CONCLUSIONS

Many of the findings of the research confirm what is

already stated in the literature on topics such as

gender and sexual diversity. The interconnection

with the dominant heteronormative culture of

Indonesian society is also apparent from the

findings.

Regarding online cultures, they have made a

difference in the ease of finding sexual partners or

friends, and serve as a safe space for gay men and

MSM to interact with each other. It is such a safe

space that many respondents are quite open about

their identities and desires, which means that online

cultures are becoming sub-cultures in Indonesia. In

future research, it would be interesting to compare

the issue of subversive sexual identity to other

subversive online cultures or sub-cultures such as

punk, child-free, erotic animation and the like.

Another finding that is worth noting is the fact

that young gay men and MSM form a significant

percentage of the respondents. This corroborates

with surveys on sexual behaviour conducted within

HIV programs that found that increasingly younger

gay men and MSM start their sexual experiences

early and some are diagnosed with HIV at an early

age (in their teens).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the core activists at

GAYa NUSANTARA Foundation who took part in

the discussions on the issues to be explored, on the

questions to be included in the questionnaire and on

the try out of the draft questionnaire. We particularly

thank Rafael H. Da Costs (Vera Cruz), (Sam)

Slamet, SardjonoSigit and PurbaWidnyana. Along

the way we were joined by Astrid Wiratna,

LastikoEndiRahmantyo, Kathleen Azali, the late

MaimunahMunir. We thank the community

members who readily filled in both the online and

the offline questionnaires and thereby shared their

lives. We finally thank volunteers and staff of GAYa

NUSANTARA Foundation who have been involved

in the different steps of the research.

REFERENCES

Berry, C, Martin, F and Yue, A, 2003. Mobile Cultures:

New Media in Queer Asia. In Canadian Journal of

Communication, Vol. 29 (2) NC: Duke University

Press

Boellstorff, T, 2005. The Gay Archipelago: Sexuality and

Nation in Indonesia, Princeton University Press.

Princeton and Oxford.

Butler, J. 2004. Undoing Gender, Routledge. New York &

London

Hall, S & du Gay, P (eds), 1996. Questions of Cultural

Identity, SAGE Publications. London, New Delhi

Hill, D.T &Sen, K, 2005. The Internet in Indonesia’s New

Democracy, Routledge. London & New York

Henrickson, M, 2007.A queer kind of faith: Religion and

spirituality in lesbian, gay and bisexual New

Zealanders, Aotearoa Ethnic Network Journal

Klinkenberg D & Rose S, 1994.Dating scripts of gay men

and lesbians. Journal Homosex. 26:23–35

Lim, M, 2002.CyberCivic Space in Indonesia: From

Panopticon to Pandemonium?. In International

Development and Planning Review Journal, special

edition, November

UNDP. 2014. Being LGBT in Asia: Indonesia Report.

Bangkok.

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

172