Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Aborigine

Children in Kampung Ulu Gerik, Perak

Anita Talib

1

, Adibah Hanum Sahari

2

and Nazar Mohd Zabadi B. Mohd Azahar

2

1

School of Distance Education, Biology Section, Universiti Sains

M

alaysia, Minden, Penang 11800. Malaysia

2

Department Faculty of Health Science, University Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Bertam, Penang, Malaysia

Keywords: Ethnobiology, intestinal parasitic infections, helminths, indigenous children, polyparasitism

Abstract: Intestinal parasitic infections among indigenous children have been identified as one of the

important public health problems among the disadvantaged population. The prevalence of these

infections causes significant illnesses and diseases among children. This cross-sectional study

was conducted to determine the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and their associated

risk factorsamong children aged 2 to 14 years in Perkampungan Orang AsliUluGerik, Perak. A

total of 75 faecal samples were obtained in this study. Results from our study showed that the

intestinal parasitic infections were prevalent among indigenous children. Infection by

Trichuristrichiura was the most common infection (65.3%), followed by Hookworm (46.7%),

Ascarislumbricoides (42.7%) and Entamoeba spp. (16.0). Only 1.3% of children had Giardia

spp. infection. More than half of the children in this study hadpolyparasitism representing 54.7%.

Social and environmental factors such as Father’s occupation (p=0.019), water sources

(p=0.039), type of toilet (p=0.026) and intake of the supplement (p=0.021) were significantly

associated with polyparasitism. Promotion of preventive measures such as deworming, increase

of awareness on healthy lifestyle and improvement in housing facilities are urgently needed to

reduce the intestinal parasitic infections in this community.

1 INTRODUCTION

Intestinal parasitic infection among indigenous

people is one of the critical public health problems

(Hartini et al., 2013). The World Health

Organization (WHO, 2015) has highlighted that 24%

of people have been infected with intestinal parasitic

infections such as protozoan infections and soil-

transmitted helminths (STH). Majority of infected

people are residing in the developing countries

(Hartini et al., 2013). Demographic changes and

rapid socio-economic development in Malaysia have

resulted in high endemic of intestinal parasitic

infection among indigenous communities especially

among children (Chin et al., 2016). In Peninsular

Malaysia, indigenous communities are minority

groups of people separated into three main tribal

groups: Semang (Negrito), Senoi and Proto-Malay

(Aboriginal Malay) consisting of 19 ethnicities

(Chin et al., 2016). They have various lifestyles,

having unique languages, knowledge systems and

invaluable knowledge of practices for the

sustainable management of natural resources

(Tarmiji et al., 2013).

The high prevalence of parasitic infection is

associated with poverty, poor environmental

conditions, lack of clean water, lack of proper faecal

disposal, growth impairment, school performance

and cognitive function of children (Norhayati et al.,

2003). Transmitting of intestinal parasites by faecal-

oral route and infection can be severe if left

untreated and if the immune system is weak

(Norhayati et al., 2003). The main presenting

symptoms for intestinal parasitic infections are

diarrhoea, fever, nausea and vomiting (Sinniah et al.,

2012). The most common STH found in Malaysia

are Ascarislumbricoides, Trichuristrichiura and

hookworm (Norhayati et al., 2003). The most

predominant intestinal protozoan infections are

giardiasis caused by Giardia duodenalis, followed

by amoebiasisand caused by Entamoebahistolytica

(Romano et al., 2011).

There are three methods of STH transmission:

direct, modified direct and through penetration of

Tallib, A., Sahari, A. and Azahar, N.

Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Aborigine Children in Kampung Ulu Ger ik, Perak.

DOI: 10.5220/0008882400970102

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research (ICMR 2018) - , pages 97-102

ISBN: 978-989-758-437-4

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

97

the skin (Sina et al., 2012). Intestinal parasitic

infections are still prevalent among indigenous

children, ranging from 66.2% to 79.8% (Rahmah et

al.,1997; Yusof and Abd. Ghani 2011; Leroy and

Chua, 2016). In 2003, the World Health

Organization (WHO) revealed that soil-transmitted

helminthiasis had an adverse effect on growth and

development of children aged 2-14 years old. Thus,

the parasitic diseases will continue to threaten the

people’s health especially among communities from

rural areas if no appropriate actions are taken to

diminish the transmission of the parasites (Hartini et

al.,2013). Since the 1930s, numbers of research have

been conducted on intestinal parasitic infection

mainly soil transmitted helminths as they are

believed to be one of the tremendous medical

importance among children living in remote areas.

Intestinal parasitic infections are significantly

associated with environmental and personal hygiene

practices (Lim et al., 2009). This study highlights the

prevalence and risk factors for intestinal parasitic

infection among aborigine children in Malaysia.

Such information is important for the respective

parties to implement strategies or intervention to

reduce the risk of getting intestinal parasitic

infection among children.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Study Site

The present study was conducted within the area of

HuluGerik, an area located in the north-eastern state

of Perak; on the east side of the state, a boundary

with the state of Kelantan, while in the north west,

with PengkalanHulu. In the south of this area is the

district of Lenggong. Bordering with Thailand on

the northeast, this area is also one of the gateways

between Malaysia and Thailand. The south-western

part of the area is Larut, Matang and Selama.

Participants from this study were children aged 2 to

14 years old residing in Perkampungan Orang Asli,

UluGerik. Data collection was started on December

2017 and ended in March 2018.

2.2 Sampling Techniques

A clean, wide-mouth screw-cap container pre-

labeled with the individual’s name and code for the

collection of faecal sample, 10% formalin, 15ml

Falcon tube, applicator wood stick, distilled water,

centrifuge, ethyl acetate, iodine 0.05 MOL/1(0.1N),

transfer pipette 3ml, microscopic slide frosted end,

microscopes coverslips and light microscope.

Stool specimens were collected from children

aged 2 to 14 years old. For children aged under 4

years, the stool collection was done by assistance

from their parents or guardians. The samples were

collected on the following day. The fresh stool

samples were added immediately with 10% formalin

and placed into the ice box before transported back

to the Parasitology laboratory, Faculty of Health

Sciences, UniversitiTeknologi MARA (UiTM)

Bertam, Penang on the same day of collection. Each

stool sample was fixed with 10% formalin and

stored at 4°C to 10°C until further analysis.

2.3 Formalin-ethyl ether Sedimentation

Techniques for Detection of

Intestinal Parasites

Stool sample fixed with 10% formalin was mixed

well using wood applicator stick. Approximately

5ml of each formalinized specimen was strained

through one layer of wet gauze into a 15ml Falcon

tube. Distilled water was added to a volume of 10ml.

The suspension was mixed well and centrifuged at

1500 rpm for 2 minutes. Then, the supernatant was

decanted using Pasteur pipette and distilled water

was added again to a volume of 10ml. By using a

micropipette, 3ml of ethyl acetate was added to each

tube. The tube was screwed with cap and shake

vigorously for 30 seconds. Then the mixture was

centrifuged with a table model centrifuge at 1500

rpm for 2 minutes. After centrifugation, it became

four layers: ether, debris, formalin and faeces. The

supernatant was discarded. The pellet was suspended

in residual water and homogenized with gentle

stirring. Slide for observation was labelled with

respondent’s identification code. A small drop of

pellet and iodine was placed on the slide for

examination.

ICMR 2018 - International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research

98

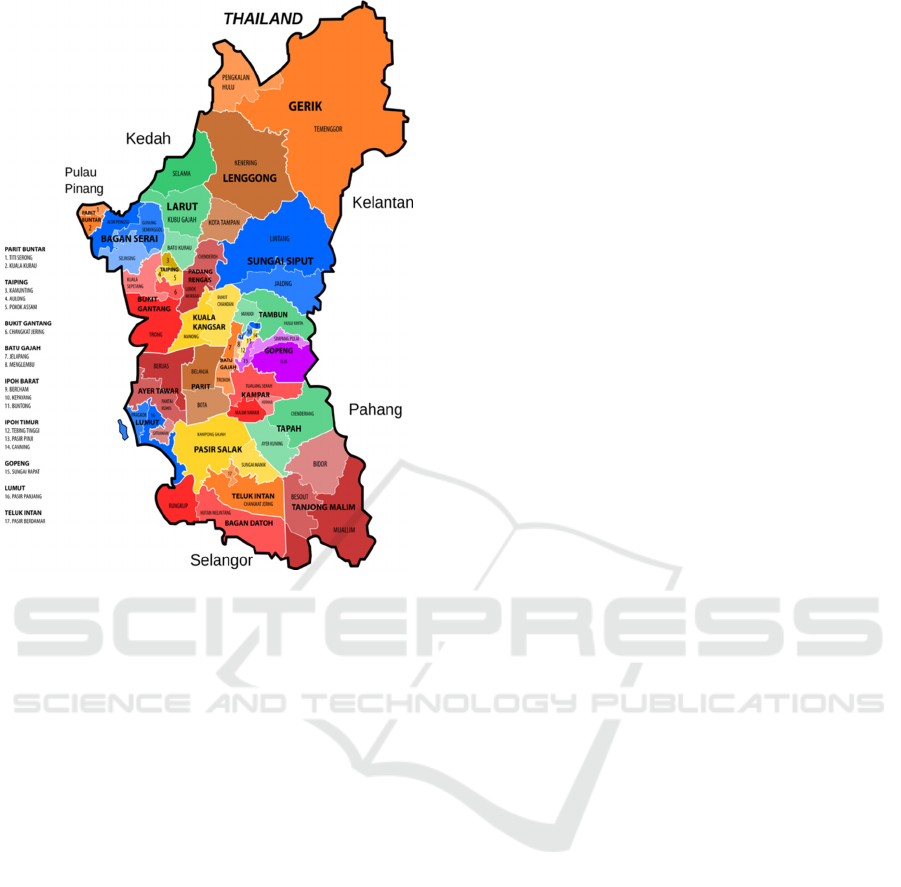

Figure 1 : The map of Perak showing the location of Gerik

(Pejabat Tanah dan Daerah Hulu Perak).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

In this cross-sectional study there were 75 children

aged 2-14 years old participated. The mean age of

children was 6.4±3.4 years. Almost half of the

children were aged 4 to 8 years (45.3%) and

majority was female representing 54.7%. A third of

children (35.7%) in this study wear shoes when they

were outside house. Almost all (96.0%) of children

in this study received complete vaccination from the

nearest government health clinics. Parental

information among children was assessed in this

study. A majority of the fathers work as rubber

tapper (54.7%) and 41.3% of them did not have any

formal education. Meanwhile, most of the mothers

were housewives (65.4%) and 53.3% of them did

not have any formal education. The mean age of

father was 40.6±9.4 years while 34.2±8.9 years for

mothers. With regards to monthly household

income, the mean was reported as RM309.3±121.0.

In reference to the family size of participants, the

mean total of kids in a family was 3.19±1.6 kids.

Meanwhile, more than half of the respondents

(53.3%) did not receive any financial assistance to

support their daily life. With regards to their housing

facilities, 45.3% of the respondents used treated

water sources, 58.7% have television and 48% had

radio. About two-thirds of the respondents (69.3%)

did not have toilet facilities in their home while 68%

of the respondents did not have proper defecation

place status. Only 40% of the respondents had pet at

their home. Nearly half of the respondents (46.7%)

took supplement as their additional food. All

respondents received antihelminthic agents and did

not have any systematic garbage disposal (Table 1).

There were five intestinal parasites identified in

this study: Trichuristrichiura, Ascarislumbricoides,

Hookworm, Giardia spp. and Entamoeba spp. In

total, 65.3% of children were infected by

Trichuristrichiura, followed by Hookworm (46.7%),

Ascarislumbricoides (42.7%) and Entamoeba spp.

(16.0%). Only one child was infected by Giardia

spp. and, 12.0% of children did not have any

intestinal parasitic infection. Intestinal parasitic

infection by Trichuristrichiurawas the highest

among male and female children representing 64.7%

and 65.9% respectively. In total, there were 33.3%

of children withmonoparasitism, 30.7% two

parasites, 18.7% three parasites and 5.3% four

parasites. The prevalence of children with

polyparasitism (having at least two types of

infection) in this study was 54.7%. The prevalence

of intestinal parasitic infection by gender in this

study was presented in Table 2. Our results showed

that Trichuristrichiura was the highest intestinal

parasitic infection among children. Similar to studies

done by previous researchers in other sub-ethnic

groups (Chin et al, 2016; Delaimy et al., 2014; Nasr

et al., 2013; Ngui et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2014;

Anuar et al., 2014; Sinniah et al., 2012). Delaimy et

al., (2014) found that almost all children were

positive for Trichuristrichiura infection (95.6%).

One of the factors for the high prevalence of

Trichuristrichiura infection might be due to

occurrence of super infection. This occured when

the children harboring the parasite was re-infected

with similar parasite especially due to ineffective

treatment against this infection (Ng et al., 2014). Our

results also showed that Hookworm was the second

highest intestinal parasitic infection. This finding is

contradictory with studies done by other researchers

(Chin et al., 2016; Nasr et al., 2013; Ngui et al.,

2015; Anuar et al., 2014) whereby the infection by

Ascarislumbricoides is the second most common

intestinal parasitic infection among indigenous

population followed by Hookworm infection. This

might be due to the fact that the current study was

conducted among Temiar sub-ethnic group

meanwhile the previous studies were conducted

Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Aborigine Children in Kampung Ulu Gerik, Perak

99

among Temuan and MahMeri sub-ethnic groups.

Since the prevalence of infection by

Trichuristrichiura, Hookworm and

Ascarislumbricoideswere high, this study

hypothesized that the soil contamination with these

parasites was higher in this indigenous community.

In addition, most of the children in this study did not

wear shoes (64.3%) and 68% of them did not have

proper defecation place status. This will increase the

rate of intestinal parasitic transmission in the

community. However, this hypothesis should be

further confirmed with soil analysis. The finding of

the present study showed that most of the children

had polyparasitism (54.7%). Only a third of the

children had monoparasitism. The prevalence of

polyparasitism in this study was lower compared to

that reported by Delaimy et al., 2014 (71.4%). In

another study a much higher prevalence of

polyparasitism was found among respondents in

western Cote d’Ivoire (Raso et al., 2014). However,

the prevalence of polyparasitism in the current study

was slightly higher compared to a study conducted

by Chin et al., 2016. They found that the prevalence

of polyparasitism among Temuan and Mah-Meri

was 41.5% and 32.5% respectively. Current findings

indicate that the environment among indigenous

population is heavily contaminated with the

parasites. It is important findings because children

with polyparasitism may suffer from multiple

morbidity due to each species infection (Booth et al.,

1998).

Table 1: Socio-demographiccharacteristics of respondents.

Socio-

demographic

characteristics

Frequency

(n)

Percentage

(%)

Age groups (n=75)

- Less than 4 years

- 4-8 years

- 9-12 years

20

34

21

26.7

45.3

28.0

Sex (n=75)

- Female

- Male

41

34

54.7

45.3

Wear shoe (n=70)

- Yes

- No

25

45

35.7

64.3

Father’s occupation

(n=75)

- Farmer/Hunter

- Rubber tapper

34

41

45.3

54.7

Mother’s occupation

(n=75)

- Rubber tapper

- Housewives

26

49

34.7

65.3

Father’s educational

level (n=75)

- No formal education

- Primary school

- Secondary school

31

29

15

41.3

38.7

20.0

Mother’s educational

level (n=75)

- No formal education

- Primary school

- Secondary school

40

29

6

53.3

38.7

8.0

Completed

vaccination (n=75)

- Yes

- No

72

3

96.0

4.0

Received financial

assistance (n=75)

- Yes

- No

35

40

46.7

53.3

Water sources (n=75)

- Treated

- Not treated

34

41

45.3

54.7

Own television

(n=75)

- Yes

- No

44

31

58.7

41.3

Own radio (n=75)

- Yes

- No

36

39

48.0

52.0

Type of toilet (n=75)

- No toilet facilities

-Proper toilet facilities

52

23

69.3

30.7

Defecation place

status =(n=75)

- Other places

- Proper toilet

51

24

68.0

32.0

Own pet (n=75)

- Yes

- No

30

45

40.0

60.0

Garbage disposal

(n=75)

- Systematic

- Not systematic

0

75

0

100

Antihelminthic drugs

(n=75)

- Yes

- No

75

0

100

0

Supplement (n=75)

- Yes

- No

35

40

46.7

53.3

Mean respondent’s

age

6.4±3.4

Mean father’s age 40.6±9.4

Mean mother’s age 34.2±8.9

Mean household

income (RM)

309.3±121.0

ICMR 2018 - International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research

100

Table 2: Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection by

gender.

Intestinal

parasitic

infection

Male Female Total

n % n % n %

Helminth

infection

- Trichuristric

hiura

- Ascarislumbr

icoides

- Hookworm

22

10

15

64.7

29.4

44.1

27

22

20

65.9

53.7

48.8

49

32

35

65.3

42.7

46.7

Protozoan

infection

- Giardia

spp.

- Entamoeba

spp.

1

4

2.9

11.8

0

8

0.0

19.5

1

12

1.3

16.0

No intestinal

parasitic

infection

4 11.8 5 12.2 9 12.0

Monoparasitism 15 44.1 10 24.4 25 33.3

Two parasites 10 29.4 13 31.7 23 30.7

Three parasites 3 8.8 11 26.8 14 18.7

Four parasites 2 5.9 2 4.9 4 5.3

Polyparasitism 15 44.1 26 63.4 41 54.7

4 CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study show the existence

of intestinal parasitic infection among aborigine

children. The prevalence of Trichuristrichiura

infection is the highest in this study and there are

54.7% of respondents withpolyparasitism.

Significant risk factors for polyparasitismare father’s

occupation, water sources, type of toilet facilities

and intake of supplement. Findings from this study

provide information for the responsible agencies to

promote strategic plans to reduce the rate of

intestinal parasitic infection among aborigine

community. Our study highlights the possibility that

polyparasitism could be affecting the health of

young children especially in indigenous

communities, hence Malaysian government should

put on more efforts on preventive measures such as

socio-economic development programmes to

increase knowledge and awareness and to educate

the aborigine community about disease control such

as periodic chemotherapy, provision of safe water

and improvement in hygienic practices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Acknowledgements to School of Distance

Education, USM for the support granted to this

research in collaboration with Department of Faculty

of Health Science, University Teknologi MARA

(UiTM) Bertam, Penang. Gratitude is extended to

the staff ofJabatanKemajuan Orang Asli (JAKOA) ,

and Head of Department of Faculty of Health

Science, University Teknologi MARA (UiTM)

Bertam, Penang, En. Amir Herberd B Abdullah at

Clinical Research Laboratory for their support and

assistance.And to Head of Villages atPerkampungan

Orang AsliUluGerik, Perak and their respective

committees for their assistance in data collection.

REFERENCES

Anuar, T.S., Salleh, F.M., Moktar, N., 2014. Soil-

transmitted helminth infections and associated risk

factors in three Orang Asli tribes in Peninsular

Malaysia.Sci Rep 4:4101.

Booth, M., Bundy, D.A.P., Albonico, M., Chwaya, H.M.,

Alawi, K.S., Savioli, L., 1998. Associations among

multiple geohelminth species

Chin, Y. T., Lim, Y. A. L., Chong, C. W., The, C. S. J.,

Yap, I. K. S., Lee, S.C., Tee, M. Z., Siow, V.W.Y and

Chua, K. H., 2016. Prevalence and risk factors of

intestinal parasitism among two indigenous sub-ethnic

groups in Peninsular Malaysia. Infectious Disease of

Poverty 5: 77.

Delaimy, A.K., Al-Mekhlafi, H.M., Nasr, N.A., Sady, H.,

Atroosh, W.M., Nashiry, M., et al.,

2014.Epidemiology of intestinal polyparasitism among

Orang Asli school children in rural

Malaysia.PLoSNegl Trop Dis 8:e3074.

Hartini, Y., Geishamimi, G., Mariam, A.Z., Mohamed-

Kamel, A.G, Hidayatul, F.O. and Ismarul, Y.L., 2013.

Distribution of Intestinal Parasitic Infections Amongst

Aborigine Children at Post Sungai Rual, Kelantan,

Malaysia. Tropical Biomedicine 30(4): 596-601.

Lee, S.C., Ngui, R., Tan, T.K., Muhammad Aidil, R., Lim,

Y.A.L., 2014. Neglected tropical diseases among two

indigenous subtribes in peninsular Malaysia:

highlighting differences and co-infection of

helminthiasis and sarcocystosis. PLOS One

9:e107980.

Leroy, A.L., Chua, T. H., 2016. Worm infection among

children in Malaysia.Borneo journal of medical

sciences. 10(1) :59-74

Lim, Y.A.L, Romano, N., Colin, N., Chow, S.C. and

Smith, H.V., 2009. Intestinal parasitic infections

amongst Orang Asli (indigenous) in Malaysia: Has

socioeconomic development alleviated the problem?

Tropical Biomedicine 26(2): 110-122.

Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Aborigine Children in Kampung Ulu Gerik, Perak

101

Nasr, N.A., Al-Mekhlafi, H.M., Ahmed, A., Roslan, M.A.,

Bulgiba, A., 2013.Towards an effective control

programme of soil-transmitted helminth infections

among Orang Asli in rural Malaysia. Part 1:

prevalence and associated key factors. Parasit Vectors

6:27.

Ng, J.V., Belizario,J.r. V.Y, Claveria, F.G., 2014.

Determination of soil-transmitted helminth infection

and its association with hemoglobin levels among

Aeta schoolchildren of Katutubo Village in Planas,

Porac, Pampanga. Phil SciLett. 7: 73–80.

Ngui, R., Aziz, S., Chua, K.H., Aidil, R.M., Lee, S.C.,

Tan, T.K., et al., 2015. Patterns and risk factors

Norhayati, M., Fatmah, M.S., Yusof, S. and Edariah, A.B.,

2003. Intestinal parasitic infection in man: A Review.

Medical Journal of Malaysia 58: 296-305

Pejabat Tanah dan Daerah Hulu Perak.Geografi Daerah.

http://pdtgerik.perak.gov.my/profil/informasi-

daerah/geografi-daerah. Access on 30 September 2017

Rahmah, N., Ariff, R.H., Abdullah, B., Shariman, M.S.,

Nazli, M.Z. and Rizal, M.Z., 1997. Parasitic infections

among aborigine children at Post Brooke, Kelantan,

Malaysia.Medical Journal of Malaysia 52: 412-414.

Raso, G., Luginbu¨hl, A., Adjoua, C.A., Tian-Bi, N.T.,

Silue´, K.D., et al., 2004.Multiple parasite infections

and their relationship to self-reported morbidity in a

community of rural Coˆte d’Ivoire.Int J Epidemiol 33:

1092–1102.

Romano, N., Saidon, I., Chow, S.C., Rohela, M. and

Yvonne, A.L.L., 2011.Prevalence and Risk Factors of

Intestinal Parasitism in Rural and Remote West

Malaysia.PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 5(3):

e974.

Sina, H., Akre, M.A., Alia, T. and Neil, A., 2012.Soil-

transmitted helminths.Global Health Education

Consortium.

Sinniah, B., Sabaridah, I., Soe, M.M., Sabitha, P., Awang,

I.P.R., Ong, G.P. and Hassan, A.K.R., 2012.

Determining the prevalence of Intestinal Parasites in

Three Orang Asli (Aborigines) communities in Perak,

Malaysia.Tropical Biomedicine 29(2): 200-206.

Tarmiji, M., Fujimaki, M., Norhasimah, I., 2013. Orang

Asli in Peninsular Malaysia: Population, Spatial

Distribution and Socio-Economic

Condition.www.ritsumei.ac.jp/acd/re/k-

rsc/hss/book/pdf/vol06_07.pdf. Access on 11

November 2017.

World Health Organization : Soil-transmitted helminth

infections. Fact sheet no. 366 updated May 2015.

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs366/en/

Accessed 09 February 2018.

Yusof, H. and Abd.Ghani, M.K., 2011. Intestinal parasitic

infections among Orang Asli children at PosLenjang,

Pahang.First Regional Health Sciences and Nursing

Conference 2011.

ICMR 2018 - International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research

102