Tourism Vocational Education Versus Tourism Industry

Elni Jeini Usoh, Linda Lambey, Daniel Adolf Ohyver, Parabelem Tinno Dolf Rompas, Julyeta

Paulina Amelia Runtuwene, and Mercy Maggy Franky Rampengan

Universitas Negeri Manado

Keywords: Vocational Education, Tourism Industry, Tourism Indonesia

Abstract: The tourism vocational education has provided qualified human resources to meet the tourism industry

requirements. However, there is a big gap exist between the graduates, curriculum design and the demands

from tourism industry because of the dynamic nature and shifted trends in it. The paper’s objective is to

present a review of current tourism vocational education in Indonesia, examined the curriculum of tourism

vocational education and compare to tourism industry requirements. The method of this study used

qualitative methodology through comprehensive literature review on curriculum, supporting documents and

regulations. Interviews were conducted with educators from tourism vocational education and relevant

stakeholders in tourism industry which involved 15 respondents. The data were analysed by using thematic

content analysis through NVivo software analysis and manual system. The results of this research indicated

that the tourism vocational institutions should collaborate with stakeholders to recognize the industry’s

requirements to develop relevant curriculum. In relation to provinces in Indonesia which has unique culture

and abundant natural resources, the graduates need some specific skills to cater the relevant demands in

tourism industry. The vocational institutions should be proactive to develop their curriculum, improve

graduates’ quality and added specific skills required.

1 INTRODUCTION

Education is a crucial thing for nation’s development

and act as a strong pillar to build the nation welfare.

Therefore, it is a need to elevate education quality

and keep it up to date with the global trends. The

quality improvement of education may give an

impact to many sectors related. It is evident that

education have an important role to human capital.

Education is a fundamental aspect of a human, and

act as a central point to reveal human capabilities.

Education is a powerful tool which can boost human

capital, productivity, incomes, employability, and

economic growth. Human capital and education are

accepted as significant factors in economic growth

(Romer, 1986, Lanzi, 2007).

Thus, it is noticeable that education builds

human capital which lead to economic growth.

Human capital may lift the economic growth, first,

in improving the capability to absorb and adapt new

technology and second involvement in rapid grow of

advanced technology (Romer 1986). Burgess (2016)

also confirms that there are several reasons why

education quality is critical, first, because education

may become a nation’s stock of skills which so

potential to economic growth to lead the highly

competitive international environment. Second,

human capital is the factor to determine income

inequality, moreover the high payment of expertise

in certain skills. Third, the relation between human

capital and their background is a vital determinant of

social mobility and endurance of difficulty.

Human capital is a main factor which

differentiate countries and as important aspect to

compete both in regional or global arena (Sipilova,

2013). As a member of ASEAN Economic

Community which begin in 2015, Indonesia is

racing to compete with other ASEAN countries in a

free market, generally in the context of capital,

goods and services and labour. In the World

Economic Forum (WEF) ranking, Indonesia

experienced a big leap from 50 to 38. This was a

huge leap for Indonesia and only surpassed by

Ecuador and Lesotho. However, Indonesia’s ranking

still under the ratings of other ASEAN countries,

especially Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and Brunei

Darussalam. This situation put a big question for

public whether Indonesia could compete among

488

Usoh, E., Lambey, L., Ohyver, D., Rompas, P., Runtuwene, J. and Rampengan, M.

Tourism Vocational Education Versus Tourism Industry.

DOI: 10.5220/0009013404880494

In Proceedings of the 7th Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and Application on Green Technology (EIC 2018), pages 488-494

ISBN: 978-989-758-411-4

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

ASEAN countries. Currently the Human

Development Index (HDI) Indonesia was ranked

121st out of 187 countries. Based on the report of

the World Economic Forum (WEF, 2016),

Indonesia’s competitiveness in ranked 37 and still

lower compared to some neighborhood countries

such as Singapore (ranked 2nd), Malaysia (ranked

18th) and Thailand (ranked 32nd). In refer to the

global talent competitiveness index 2015–16

Indonesia in ranked 90 for low middle-income

countries. In fact, the structure of the Indonesian

workforce pointed at a total of 55.3 million (46.8%)

only graduated from elementary school (Taty,

Possumah, Razak, 2017).

The tourism industry in Indonesia is developing

rapidly and presents a great contribution to

Indonesia’s national revenue. In recent time The

Indonesian Ministry of Tourism has been awarded as

the best National Tourism Organisation in TTG

(Travel Trade Gazette) Travel Awards 2018 in

Bangkok. Moreover in 2018, Indonesia ranked in

second position in Global Moslem Travel Index as

the nation has raised 14,000 foreign tourists in 2017

(Kurniawan, 2018).

The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC)

Integration in 2015 has the movement of

employment for skilled tourism labor. The main

purpose is to recognise of skills and qualifications

required for working tourism professionals in

ASEAN countries. The 2002 ASEAN Tourism

Agreement (ATA) also guaranteed to upgrade

tourism education, curricula and skills through the

setting up competency standards and certification

procedures, which lead to a mutual recognition of

skills and qualifications in the ASEAN region

(Batra, 2016).

There are a lot of opportunities in the tourism

industry and needs to be maintained very well so

that we can keep or upgrading the achievement. In

terms of tourism vocational education, the graduates

should be ready and qualified for this rapid changing

in tourism industry. This urge Indonesia to provide

tourism education in order to have the qualified

graduates from tourism education and modify the

curriculum to enhance the competitiveness in

ASEAN countries and in global arena.

This paper attempts to describe the gap between

the tourism school graduates and industry, examine

the current tourism curriculum by taking the key

perspectives from tourism schools or tourism higher

education in Indonesia and compare to the tourism

industry requirements.

2 ROLE OF TOURISM

VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

Technology and Higher Education Ministry reported

that there are 1,238 state and private polytechnic

education institutions in 2017. It is noticeable that

vocational higher education has progressed with the

establishment of more state polytechnics in the past

two decades. Recently, the target for vocational

education is to equip graduates to have competence

and professionals so they can compete at a regional

and global level.

Polytechnic education and vocational school play

an important role in human resource development of

a country by creating professional and skilled

manpower, enhancing industrial productivity and

improving the quality of life. Indonesia has tourism

vocational training schools and academies in most

provinces and some tourism polytechnic under the

authority of Tourism Ministry in several provinces.

Tourism vocational education has significant

contribution to tourism industry in Indonesia.

The Indonesian Qualification Framework is

regulated by the Directorate General of Higher

Education, Ministry of Education and Culture,

Republic of Indonesia, and based on Presidential

Decree No. 8/2012. The framework comprises nine

levels of qualifications, starts from Level 1 to Level

9. The nine qualifications are clustered into three

components: operator (Levels 1–3), technician or

analyst (Levels 4–6), and expert (Levels 7–9). The

vocational and the academic bachelor programs are

both categorized as Level 6. The lower level

emphasise the development of practical skills,

whereas the upper level on knowledge and science

(Oktadiana & Chon, 2014; Silitonga, 2013).

The vocational bachelor, as ruled by the

Directorate General of Indonesian Higher Education,

is equivalent to the traditional academic bachelor in

terms of the levels approach. The bachelor’s degree

requires a total number of credit units between 144

and 160 to be completed within 4 years of study

(DIKTI, 2011). There were approximately 25

hospitality and tourism institutions offering

vocational and/or academic bachelor programs.

However, the development of the institutions grows

slowly because of several issues, such as a lack of

strategic initiatives; regulations changes; a lack of

integration among tourism and hospitality educators;

academic regulations, accreditation system,

nomenclature, and inadequate research activities

(Oktadiana & Chon, 2014; Sofia, 2013).

The vocational education in Indonesia has been

modified several times to fit the political and other

Tourism Vocational Education Versus Tourism Industry

489

environment changes (Galam, 1997). Indonesian

government conducted programs to enhance tourism

instructors’ knowledge, skill, and professionalism in

massive education trainings (Park, 2005).

Despite the slow progression of tourism

institutions in Indonesia, it is noticeable that the

purpose of tourism vocational education is to

provide the professional graduates to work in

tourism and hospitality industry.

2.1 Gap between Graduates,

Curriculum and Industry

Although tourism curriculum has been established

decades ago and evolved for improvement, a gap

still occurs between the graduates, curriculum and

tourism industry.

Many Indonesian polytechnic graduates remain

unemployed. There is also a mismatch of skills

between what vocational graduates offer and what

employers need. Furthermore, there is still the

problem of making vocational higher education

attractive to Indonesians. (Ayuningtyas, 2017).

To some extent, the tourism curriculum is

insufficient to fit in the industry’s demands because

of some differences between the results provided by

hospitality and tourism institutions and the

requirements from industry (Ernawati, 2003). In

addition, this area of study is still considered as less

academic and prestigious compare to other

traditional subject areas. Students opted hospitality

and tourism study because they assume it as a course

with many practical activities and requires

nonmathematical skills (Oktadiana, 2011).

The skilful graduates and curriculum are the

essential things that need to be addressed in the

changing employment market and technology

advances. The gap between graduates, curriculum

and industry still occurs because of several issues

identified such as: the existing tourism curricula do

not adjust with the changes of the tourism industry;

courses in tourism institutions are too broad or lack

focus; insufficient practical experience for students;

ineffectiveness English/foreign language training;

inability to apply theory courses to the actual

tourism industry work-place environment;

instructors are more focused on teaching material

that cover their main interests, teaching material not

updated regularly; textbooks are very expensive

especially from international publishers or written

by international instructors who focus on issues and

environments which different from tourism

perspectives in their own areas (Batra, 2016).

2.2 Review of Tourism Vocational

Education Curriculum

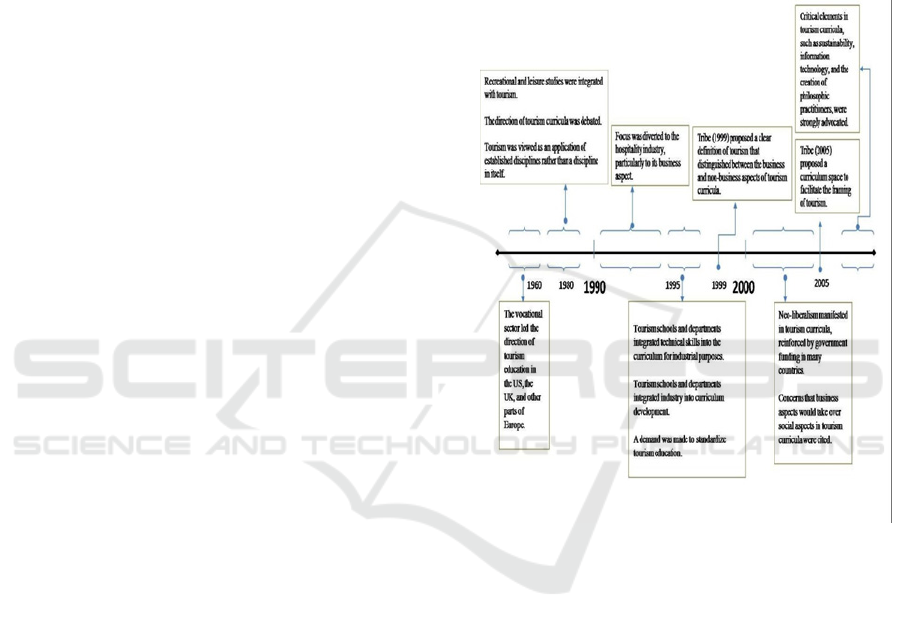

Tourism curriculum development, as showing in

Figure 1 can be divided into three main period; first,

before 1990, second, between 1990 and 2000, and

third from 2000 to the present. The development

timeline of tourism studies embodies the dynamic

views of the educational tourism community during

these periods (Wattanacharoensil, 2014).

Figure 1: Key events of tourism curriculum development

in each period (Adapted from Wattanacharoensil, 2014).

The arguments about curriculum content and the

balance of courses in hospitality and tourism

education have been continuing. The Tribe’s

perception suggested that the tourism and hospitality

curriculum should consist of “vocational,

professional, social science and humanities

knowledge and skills that promote a balance

between satisfying the business demands and those

required to operate within the wider tourism world”

(Dredge et al, 2012; p. 20).

The hospitality curriculum should emphasise not

only on technical skills but also on the general

management skills which are significant for the

graduates’ long-term careers. The conceptual skill is

needed to cope with the complexity of hospitality

operations. The balance of liberal arts and

specialized education is required is required (Lin,

EIC 2018 - The 7th Engineering International Conference (EIC), Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and

Application on Green Technology

490

2002). Both of generic skills and vocational skills

are fundamental for tourism and hospitality

education curriculum. Generic skills may consist of

communication, numbers application, problem

solving, teamwork, information technology, personal

values, and attitudes in example: leadership,

motivation, initiative, and discipline) (Rimmington,

1999).

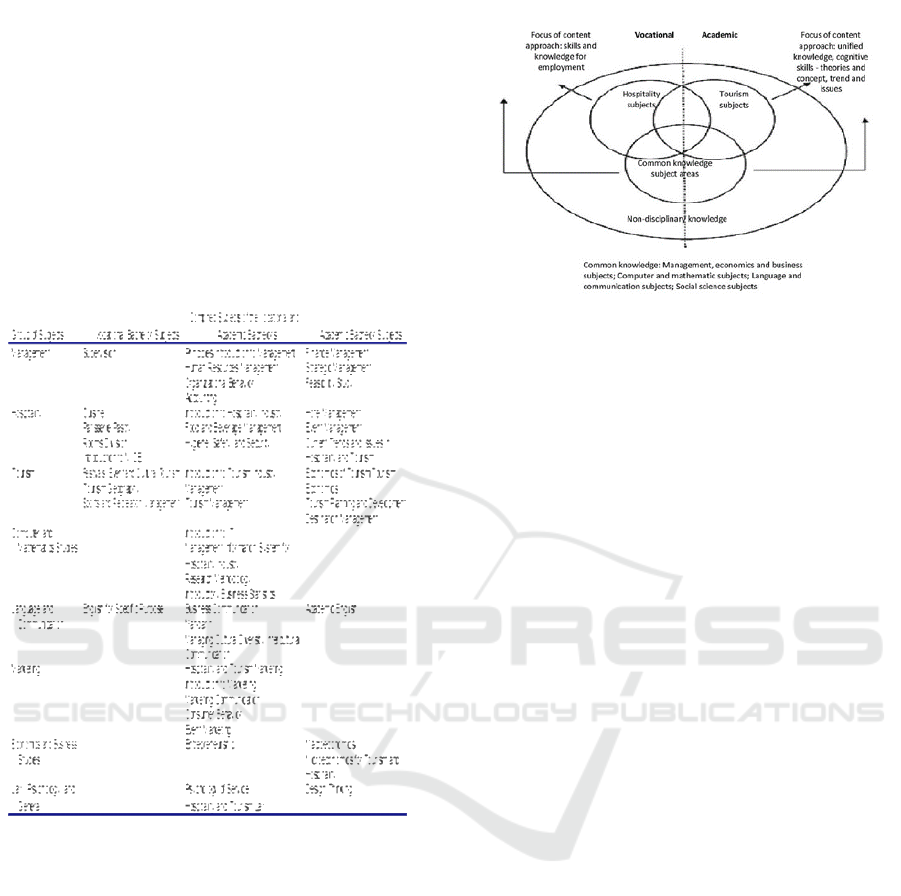

The study of Oktadiana and Chon, 2017

summarised the combined subject that can be

thought in tourism and hospitality curriculum for

Bachelor degree which is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Course content of vocational and academic

bachelor programs (Adapted from Octadiana & Chon,

2017).

The content-specific focus of the vocational

bachelor program is on the hospitality subjects

whereas the academic bachelor highlights the

tourism subjects. A proposed course contents can be

seen at Figure 3.

Figure 3: A proposed model of vocational and academic

bachelor course content (Adapted from Oktadiana and

Chon, 2017).

In summary, the focus courses for the vocational

mode is on skills and knowledge for employment,

whereas for the academic mode it is on integrated

knowledge and cognitive skills that emphasis on

theories, concept, trends and issues in tourism

(Oktadiana & Chon, 2017).

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research used exploratory qualitative research

method. The data obtained from the in-depth

interview result, literature about curriculum in

tourism education, collecting the relevant documents

and observation.

3.1 Data Collection Technique

Data collection techniques are through interviews,

documents and research notes from observations

(field notes) (Zhang, 2008a, Zhang 2008b).

1. Interview

Interviews generate direct quotes from

respondents about the experiences, opinions,

feelings and knowledge of respondents (Patton,

2005). The interview was conducted in the form

of in-depth interviews. This technique is a

qualitative research that include intensive

individual interviews with a small number of

respondents to explore their perspectives on a

specific idea, program or situation (Boyce &

Neale, 2006). The interview conducted in the

form of semi-structured interviews. The semi-

structured interview considered to be the most

appropriate for this study because it can explore

the perceptions and opinions of the respondents

and to obtain further information or clarification

of the questions. In addition, semi-structured

interview form can be implemented on the

respondents who are professional and educated

as well as the appropriate standard interview

schedule (Barriball & While, 1994)

Tourism Vocational Education Versus Tourism Industry

491

2. Documentation

The relevant documentation related curriculum,

tourism curriculum, rules and regulations

concerning the curriculum in Indonesia.

3. Observation

Researchers did observations by noting the

important and relevant data to the purpose of

research.

3.2 Data Analysis Technique

In this study, interview results were analysed using

thematic content analysis. Thematic content analysis

is an analytical method to describe phenomena

commonly used in qualitative business,

psychological and health research (Downe-

Wambolt, 1992; Elo & Kyngas, 2008; Hsieh &

Shannon, 2005). The data generated from this

research is the result of semi-structured interviews in

the form of audio-tape recordings, documents and

field notes. Documentation and observation results

(field notes) analysed and selected based on

relevance to the interview results. Interview

transcripts are coded and partially processed using

NVivo software and some were done manually.

NVivo data analysis software can assist researchers

in transcribing interviews, coding and organizing

data from interviews to generate concepts of

research results (O'Donoghue, 2007). The researcher

recorded each interview process, issues related to

interview answers and other additional information.

The transcript was read, and the narrative meanings

were identified with the codes. The codes were

reviewed again and developed in the form of

"themes". The codes are then developed with

NVivo. Some notes were written manually, and

transcript interviews were made in hardcopy. This

study has the possibility of inaccurate data collection

and interpretation. In addition, researchers have

limitations in the presentation of research results in a

comprehensive and precise. Recognising these

possibilities, researchers applied triangulation

protocols, which include triangulation of data

sources, research and theories, and methodologies,

so the validity and reliability of the research can be

maintained.

3.3 Respondents and Selection Criteria

Interviews were conducted to the tourism educators

and other tourism stakeholders, who have experience

and involved in tourism teaching activities and

tourism industry. Respondents were selected

randomly. The number of respondents in this study

were 15 respondents with the duration of the

interview for 45 minutes - 1 hour.

Interview conducted with guidance of research

instrument containing questions. After the interview,

respondents had the opportunity to read the

transcript of the interview and respond if necessary

before the researcher concludes the interview.

4 RESULTS

There should be a system to build the connection

between tourism curriculum and tourism industry.

This can be conducted when all the tourism

stakeholders can communicate and engage all the

aspect to minimise the gap between curriculum, the

graduates and industry. The interview result from

80% of respondents also show the agreement to

involve all stakeholders in designing and reviewing

the tourism curriculum.

This result is aligned with the study conducted

by Batra, 2016 who asserts that the discrepancy

between tourism education and tourism industry can

be encountered through these following approaches:

1. The studies of tourism industry requirement

should be conducted to create platform for

educational institutions with employers.

2. The program provided by tourism institutions

should meet industry requirements and

expectations.

3. The revitalization of tourism curriculum should

be conducted regularly to match the graduates’

skill with the industry demands.

4. Tourism industry representative should be

invited in advisory meeting board in supporting

the academics with the specific knowledge and

skills needed for their managerial and

administrative responsibilities. Moreover, to

assist in developing curriculum with

recommendation, revision, design, and the

inclusion of industry case studies.

5. To connect beginners, students and graduates’

students for workforce entry, the tourism

industry should be invited in panel discussion

and career fair.

6. Universities which provided tourism courses

should have on the job training programs to

provide students with the application of theory

to actual work.

7. To enhance the opportunity for employment the

education institutions should integrate their

curriculum with the skills required by the local,

regional and global market.

EIC 2018 - The 7th Engineering International Conference (EIC), Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and

Application on Green Technology

492

8. Expansion of the institutions to have

memorandum of understanding with national/

international tourism organisations.

9. Courses in curriculum should consider in

including studies on arts and culture as well as

foreign languages.

The result of the study also shows that there are

some specific skills needed to adjust with the

regional tourism industry requirement. The tourism

fascinate in Indonesia is mostly because of the

richness of natural resources and Indonesian culture,

therefore some tourism types are focused on

maritime tourism, eco-tourism, recreational/sport

tourism and historical tourism.

Institutional education should provide related

course to have the professional graduates who can

fill these areas. In maritime tourism, courses that can

be added such as: diving skill, marine environment;

in eco-tourism: environmental awareness, guide for

trekking; in recreational/sport tourism; surfing

course, paragliding course; in historical tourism;

arts, history, and local cultural knowledge.

The study of Yusuf, Samsura, Yuwono (2018)

also confirmed that another important issue that

appears in proposing curriculum is the consideration

of distinctive features of the Indonesian tourism

curriculum based on local culture, characteristics,

needs, and aspirations.

The most important thing in tourism curriculum

is to add the subject foreign language. Through the

open access of transportation and internet, traveling

become a trend and can be easily accessed. The

number tourists from Asian countries for example

China and Korea are increasing every year. The

respondents also confirmed that tourism nowadays is

in needed of foreign languages other than English,

for example Mandarin and Korean language. As one

of the respondents stated:

“Our city is swarmed by the tourists from China and

Korea every year yet is so difficult to find a local

guide who can speak Mandarin and Korean”

(Respondent 10/travel agent owner).

Therefore, adding foreign languages other than

English in curriculum is an urgent need for

institutions to deal with with the industry

requirements.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This research indicated that the tourism vocational

institutions should collaborate with stakeholders to

recognize the industry’s requirements to develop

relevant curriculum. In relation to the provinces in

Indonesia which has unique culture and abundant

natural resources, the graduates need some specific

skills to cater the relevant demands in tourism

industry. The vocational institutions should be

proactive to develop their curriculum, improve

graduates’ quality and added specific skills required.

To cope with the gap of tourism vocational

education and tourism industry, the institution

should thoroughly understand the concept of Penta

helix elements for stakeholders in tourism. The

stakeholder’s elements consist of Academics,

Business, Community, Government and Media. All

elements should synergise together in connecting the

tourism vocational education and tourism industry.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Appreciation is given to Universitas Negeri Manado

(Unima), especially to Prof. Juleyta P.A. Runtuwene

as the Rector of Unima and the Research and

Community Service Center (LPPM-Unima). Special

thanks to Prof. Revolson Mege as the Head of

LPPM Unima for the support to present the paper in

EIC Conference Semarang on 18 October 2018.

REFERENCES

An, M., Chen, Y. & Baker, C. J., 2011. “A Fuzzy

Reasoning anf Fuzzy-Analytical Hierarchy Process

Based Approach to the Process of Railway Risk

Information: A Railway Risk Management System”,

Information Sciences, Vol. 181, pp. 3946-3966.

Attaway, S., 2009. MATLAB: A Practical Introduction to

Programming and Problem Solving, Oxford - UK:

Bitterworth – Heinermann - Elsevier Inc.

Andric, J. M. & Lu, D. G., “Risk Assessment of Bridges

Under Multiple Hazards in Operation Period”, Journal

of Safety Science, Vol. 83, pp. 80-92.

Carbonari, S., Morici, M., Dezi, F., Gara, F. & Leoni, G.,

2017. “Soil-Structure Interaction Effect in Single

Bridge Piers Founded on Inclined Pile Groups”, Soil

Dynamics and Earquake Engineering, Vol. 92, pp. 52-

67.

Cook, W., Barr, P. J. & Halling, M. W., 2015. “Bridge

Failure Rate”, Journal of Performance of Constructed

Facility, Vol. 29, pp. 1-8.

Corotis, R. B., 2015. “An Overview of Uncertainty

Concepts Related to Mechanical and Civil

Engineering”, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in

Engineering System, Vol. 1, pp. 1-12.

Craig, R. F., 2004. Soil Mechanics, 7

th

edition, New York

– USA: Spon Press.

Duncan, J. M. & Stephen, G. W., 2005. Soil Strength and

Slope Stability, New Jersey – USA: John Wiley &

Sons Inc.

Tourism Vocational Education Versus Tourism Industry

493

Fagundes, D. F., Almeida, M. S. S., Thorel, L. & Blanc,

M., 2017. “Load Transfer Mechanism and

Deformation of Reinforced Piled Embankment”,

Geotextiles and Geomembranes, Vol. 45, pp. 1-10.

Kusumadewi, S., Hartati, S., Harjoko, A. & Wardoyo, R.,

2006, Fuzzy Multi-Attribute Decision Making (Fuzzy

MADM), Yogyakarta – Indonesia: Penerbit Graha

Ilmu.

Kusumadewi, S., 2002. Analisis & Desain Sistem Fuzzy

Menggunakan Toolbox Matlab, Yogyakarta –

Indonesia: Penerbit Graha Ilmu.

Kusumadewi, S. & Purnomo, H., 2010., Aplikasi Logika

Fuzzy Untuk Pendukung Keputusan, 2

nd

edition,

Yogyakarta – Indonesia: Penerbit Graha Ilmu.

Lee, S., 2015. “Determination of Priority Weight Under

Multi-Attribute Decision-Making Situation: AHP

versus Fuzzy AHP”, Journal of Construction

Engineering and Management, Vol. 141, pp. 1-9.

Marwoto, S., 2014. “Pemodelan Sistem Pendukung

Keputusan Untuk Pemeliharaan Jembatan Beton”,

Jurnal Teknik Sipil, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1-5.

Maula, B. H. & Zhang, L., 2011. “Assessment of

Embankment Factor of Safety Using Two

Commercially Available Programs in Slope Stability

Analysis”, Procedia Engineering, Vol. 14, pp. 559-

566.

Nezarat, H., Sereshki, F. & Ataei, M., 2015. “Ranking of

Geological Risks in Mechanized Tunneling by Using

Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP)”,

Tunneling and Underground Space Technology, Vol.

50, pp. 358-364.

Ossama Y & Barakat, W., 2013. “Application of Fuzzy

Logic for Risk Assessment using Risk Matrix”,

International Journal of Emerging Technology and

Advanced Engineering, Vol. 3, pp. 49-54.

Patel, D. A., Kikani, K. D. & Jha, K. N., 2016. “Hazard

Assessment Using Consistent Fuzzy Preference

Relation Approach”, Journal of Construction

Engineering and Management, Vol. 142, pp. 1-10.

Senouci, A., El-Abbasy, M. S. & Zayed, T., 2014. “Fuzzy-

Based Model for Predicting Failure of Oil Pipelines”,

Journal of Infrastructure System, Vol. 20, pp. 1-11.

Zadeh, L. A., 2008. “Is There a Need for Fuzzy Logic”,

Journal of Information Sciences, Vol. 178, pp. 2751-

2779.

Zatar, W. A., Harik, I. E., Sutterer, K.G. & Dodds, A.

2008. “Bridge Embankment. I: Seismic Risk

Assessment and Rating”, Journal of Performance of

Constructed Facility, Vol. 22, pp. 171-180.

EIC 2018 - The 7th Engineering International Conference (EIC), Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and

Application on Green Technology

494