Social and Political Climbing, Elite Capture, and Democracy in the

Current Indonesian Village

Bejo Untung

1

and Semiarto A. Purwanto

2

1

Program Manager, PATTIRO;

2

Department of Anthropology, Universitas Indonesia

Keywords: village law, social mobility, local political actors, West Java, Indonesia

Abstract: The paper will describe the history of inequality of state-society relations in Indonesia through case studies

on current village politics and governance. For decades, during the New Order, the villages became

subordinate to the state. The forms of leadership, recruitment, and succession, for example, are regulated by

the state through the Village Law No. 5/1979. When the law was changed by the new Village Law No.

22/1999, the villager’s participation in village administration was rising, among others through village council

or Badan Permusyawaratan Desa. Five years later the Law was amended by the newer Village Law No. 6/2004

which is believed will make village democracy better. Through ethnographic observations, we finds out how

the state agenda outlined in the formal rules govern the existing political structure at the village level. Our

study in Pabuaran Village, Sukamakmur District, Bogor Regency, West Java, shows the rise of elite capture,

elite control, and the dynamics of actors that are often different from the formal regulations. The political

situation at the national level and the interconnection of villages with urban areas we consider very

instrumental in promoting vertical mobility at the village level.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the early days of and during the New Order

characterized by strong state centralism (Rais 1986),

the cases of rural democratic and government in

Indonesia were frequently discussed by social and

political science researchers. The studies showed

diverse directions. Some said that there is a tendency

to show that democratic practices have been carried

out through the traditional order inherent in rural

communities (Mattulada 1977, Suparlan (1977).) In

contrast, Prijono and Tjiptoherijanto (1983) present a

study of 'democracy traditional' village that has been

replaced by 'guided democracy.' Another study shows

how modern political institutions are responded

differently in various regions (Sundhaussen 1991,

Husken 1994).

At the end of the New Order period, in the 1990s,

Antlöv (2002) studied village democracy from state-

society relations. He presents the fact that the village

is in a challenging position to practice democracy

because of the influential role of the state in

exercising control through leaders and community

leaders who are recruited as formal leaders. The

inauguration of state power over the village through

its leaders was carried out through various structural

efforts such as "decarbonization" by forcing people to

be faithful to Golkar and its subordinate

organizations, as well as the militarization of villages

by placing an army called by Bintara Pembina Desa

(Babinsa). These structural efforts are strengthened

through the legitimacy of Law Number 5 the Year

1979 on Village Governance.

When the Reformasi 1998 took place, many

wished for the new arrangement of political life,

including in the rural side, to change towards a more

democratic phase. Observers believe that the new

village legislation will bring the growth of rural

democracy. Finally, the enactment of Law No. 6/2014

on Villages, in this paper will be shortly called

Village Law, is believed to be able to achieve village

democracy because it has provided sufficient norms

for the functioning of Badan Permusyawaratan Desa,

shortly known as BPD, as a democratically elected

representative body (Lucas 2016; Antlöv, Wetterbeg,

and Dharmawan 2016: 166). Nevertheless, experts

caution that romanticism in traditional leadership

structures is prone to cause deviations from the basic

principles of democracy (Antlöv 2003a: 210; Benda-

Beckman 2001; Bräuchler 2010). Another threat to

348

Untung, B. and A. Purwanto, S.

Social and Political Climbing, Elite Capture, and Democracy in the Current Indonesian Village.

DOI: 10.5220/0009930303480355

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Recent Innovations (ICRI 2018), pages 348-355

ISBN: 978-989-758-458-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

the village democracy process after the new law is the

strengthening of elite capture due to the ineffective

control function by BPD. Lucas (2016) saw the

monopoly of village officials in the planning and

management stages of development projects that

should be carried out accountably.

Given the importance of low politics as an

indicator of grassroots democracy (Antlöv 2003b:

74), the social dynamics and social mobility of the

people in the rural area becomes interesting to note.

This paper will describe the movement of rural people

as political actors, the emergence of new elites, elite

control, and elite capture in a village in Bogor

regency, West Java, Indonesia. We believe that

various laws on village and village governance have

opened up opportunities for diverse actors to play

different roles in various situations.

2 METHODS

The research seeks to explain the everyday political

practices at the village level using a qualitative

approach. This approach would be able to disclose

implicit meanings, variations of actors' interpretation,

and untold arguments (Have 2004). We conducted

ethnographic research, in which the researcher

conducted participant observation in the village to

explore information about the experiences, feelings

and also the expectations of the villagers. This

observation was conducted for four months, from

March to April, continued August to September 2017.

In addition to conducting observations in the village,

we also engaged in some discussions at the national

level, by approaching the Ministry of Home Affairs

(Kemendagri), and the Ministry of Village,

Development of Disadvantaged Regions and

Transmigration (Kemendes PDTT) as two

government bodies that have authority to implement

the Village Law. The study also comes with data from

relevant document studies.

3 RESULTS

3.1 The Studied Village

This study was conducted in Pabuaran Village,

Sukamakmur District, Bogor Regency, West Java.

Located on the eastern side of the Bogor district, the

village is located approximately 40 km from

Cibinong, the capital of Bogor Regency. This village

is located on the path of the district road that connects

Cibinong with Jonggol, Sentul and Cipanas. Based on

the Village Profile (2016), Pabuaran Village is

inhabited by 11,038 people with the composition of

the male population of 5,575 people and the female

population of 5,463. They mostly work as farmers;

but some also are traders, factory workers, and

informal workers in the field of transportation.

The total area of Pabuaran is 2,400 hectares,

almost half of it is shifting cultivation area which is

1,101 hectares; then residential areas covering an area

of 250 hectares, 655 hectares of rice fields, 300

hectares of forestry, and the rest is the area of roads,

ponds, government facilities, educational facilities

and facilities of worship.

Pabuaran Village is divided into four hamlets

consist of 7 RW and 28 RT. Village head is the

highest authority in the village assisted by a village

secretary, treasurer, and some managers called

Kepala Urusan. Besides, aside from the village

administration, there are some institutions legitimized

by Village Head’s decrees, such as Program

Kesejahteraan Keluarga or PKK (family welfare

program) and Lembaga Pemberdayaan Masyarakat or

LPM (Institute for community empowerment). The

LPM is given the mandate to manage infrastructure

development in the village. The leadership in

Pabuaran equipped with a legislative called Badan

Permusyawaratan Desa or BPD (village council)

consist of representatives from the four hamlets.

There some BPD members who are directly elected,

but there are others who are chosen by the existed

members of BPD.

2.3 Changes in Village Laws an Its

Implications

The launching of Village Law in 2014 is considered

an essential momentum for better village

management. Previously, the village government was

regulated by Undang-Undang Pemerintahan Daerah

or the regional law government, namely UU no.

22/1999 which was later changed into UU no.

32/2014. The impact is that the village has no

autonomy but more as an extension of the local

government at the Kabupaten (region) level. With the

enactment of the Village Law, the village gained its

autonomy through recognition of the indigenous right

and authority at the village level.

As a consequence of the recognition of village

autonomy, through the implementation of village

laws, villages are encouraged to run more democratic

governance. The Village Law mandates the village to

organize village meetings, as a place of decision

making involving as many people as possible. The

Social and Political Climbing, Elite Capture, and Democracy in the Current Indonesian Village

349

Village Law also mandates the village to establish a

BPD as an institution that performs checks and

balances functions. Beyond that, the Village Law also

gives villagers the right to participate in the direct

supervision of the village administration. Thus, in

addition to the BPD, actually, checks and balances

function can also be done directly by villagers.

Kemendes PDTT (2016) calls this village condition a

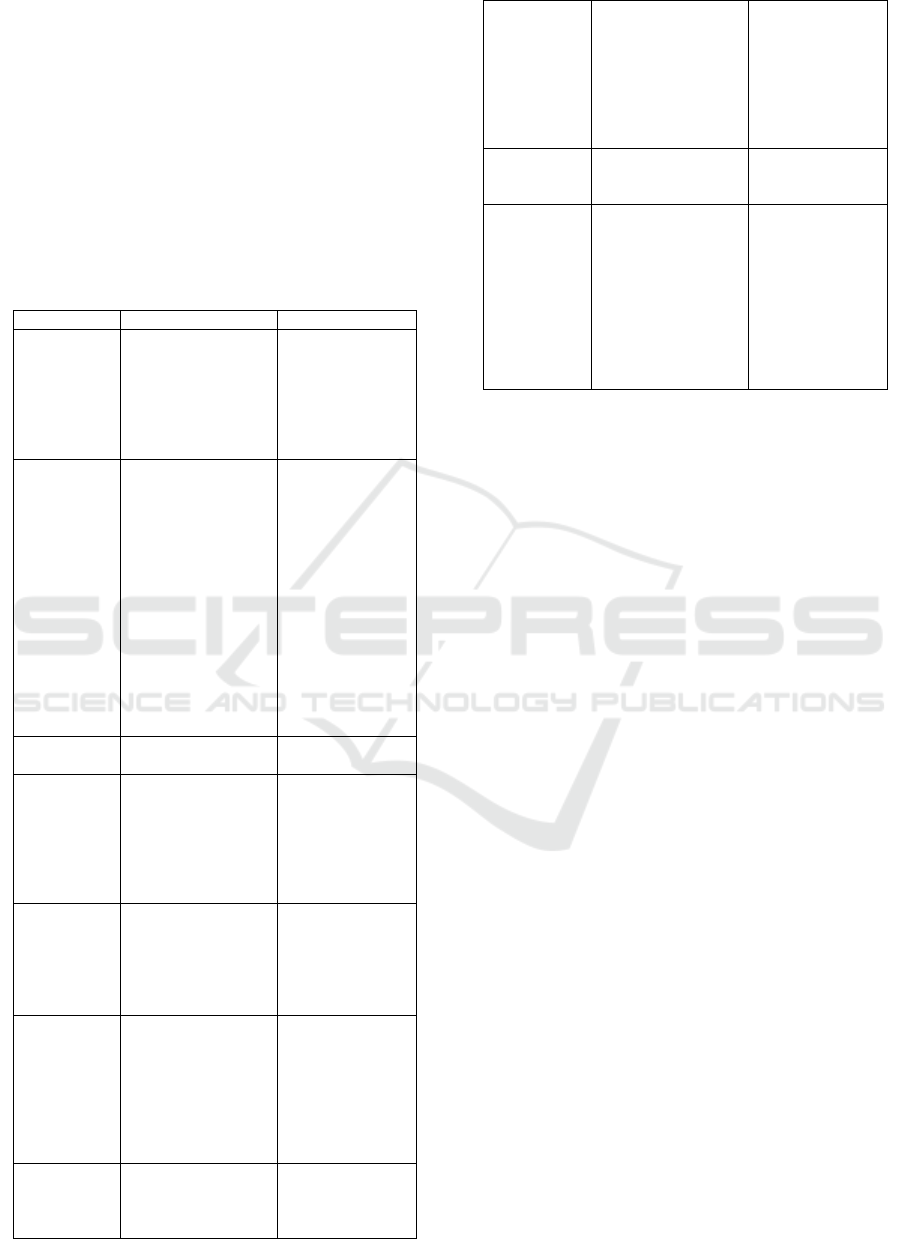

"new village." Below is the comaparison table of old

and new style of villages according to the Kemendes

PDTT

Table 1: Old and new style of villages

Elements Old villages New village

Legal

standing

1945 Constitution

Article 18 paragraph

7

Law no. 32/2004

and Government

regulation No.

72/2005

1945 Constitution

Article 18 B

paragraph 2 and

Article 18

paragraph 7

Law no. 6/2014

Vision Not clearly stated The state protects

and empowers the

village to be

strong, advanced,

independent and

democratic so as

to create a strong

foundation in

implementing

governance and

development

towards a just,

prosperous, and

prosperous

society.

Basic ideas Decentralization

Residuality

Recognition

Subsidiarity

Position Villages as

government

organizations in the

district / city

government system

(local state

government)

As a community

government, a

mixture of self

governing

community and

local self

government.

Delivery

of authority

and

programs

Target: the

government sets

quantitative targets

for building villages.

Mandate: the

state gives the

mandate of

authority,

initiative and

development.

Political

orientation

related to

place

Location: Village as

the project location

from above.

Arena: Village as

an arena for

villagers to

organize

government,

development,

empowerment

and community.

Position in

the

development

program

As an object of

development

As subject of

development

Development

model

Government driven

development or

community driven

development.

Village driven

development, with

an emphasis on

capacity building,

ownership of

economic assets

and revitalization

of village culture.

Political

characteristic

Parochial village,

and corporate

village.

Inclusive Village

Idea of

democracy

Democracy does not

become a principle

and a value, but an

instrument. Establish

elitist democracy

and participation

mobilization.

Democracy

becomes

principle, value,

system and

governance.

Establish

inclusive,

participatory and

participatory

democracy.

Source: PATTIRO Training Module 2016

Antlov considers that the enactment of the Village

Law is a sign of a better start of the village democracy

process. The law has provided the basis for the

functioning of BPD as a democratically elected

representative body and the direct involvement of

villagers (Antlöv et al. 2016: 166). Village’s

democracy is important because it is one of the

mechanisms that enable the sounding of vulnerable

and needed voices, a mechanism that allows equal

decision-making among citizens, and mechanisms

that allow anyone from diverse backgrounds to be

actively involve in politics (Antlöv 2003b: 73).

Village’s democracy is then considered as "grassroots

democracy" because it is genuinely a deliberative

space at the lowest level of government and is

believed to sustain the democracy at the national level

(Antlöv 2003b: 74).

2.3 The Case of Pabuaran Village

In practice, the Village Law does not entirely produce

a "new village" as envisaged. In Pabuaran, the village

consultation mechanism was not implemented, the

BPD also did not function properly. Village decisions

are made without involving BPD or villagers. In other

words, the village government has closed the village

democracy arena mandated by the Village Law.

Villagers then attempted to create another arena that

could be used as a means to engage in checks and

balances against village administration. This paper

presents a case example of how citizens create

channels of aspiration through some persons

considered competent to represent their interests. We

learned during the research that in fact, they were

Ucok and Haji Iding.

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

350

Although typically sound like a name of the Batak

people, Ucok is an original Pabuaran citizen aged

about 40 years. He often criticizes the Pemerintah

Desa (village government), shortly known as pemdes

if he finds something that he deems inappropriate.

Various cases have been advocated by Ucok. For

example, he once managed to dismantle the evasion

of financial aids from the Kabupaten of tapioca flour

mill by the chairman of the Gabungan Kelompok Tani

(Association of Farmers Group). These advocations

have caused Ucok to be regarded as a problem for

Pemdes and become an identical figure of resistance

to Pemdes.

Ucok's critical stance derives from his experience

as an NGO activist based in the district capital, where

he is then appointed as the subdistrict leader. With the

mandate to oversee the government budget, Ucok

then actively supervise various development

activities conducted in the villages. In Pabuaran, he

found that the use of village funds for betonisasi

(concrete road program) is not transparent. The

request for the document of development budget plan

to Pemdes is not fulfilled. Ucok wants to know the

amount of the actual development fund, to be

compared with the implementation in the field. He

found the concrete road section using an appropriate

machine was just a road past the kampung

(neighborhood) where the village head lived.

According to Ucok, this is unfair, and he seeks to stop

the betonisasi. This effort was foundered because

Pemdes called police personnel from the sub-district

sector to crack down on Ucok.

Unlike Ucok, Haji Iding is a senior figure of about

70 years old. Known for his experience of defending

the citizens involved in legal cases, Haji Iding then

became the person who was asked for advice on all

the problems faced by the citizens. We observed

when Haji Iding facilitated the complaints of

residents who felt harmed by the Lembaga

Pemberdayaan Masyarakat/LPM (Institute for

village empowerment) because they were asked to

pay Rp 50,000 per household to finance the village

road. The LPM Chairman considers it necessary to

levy because the costs provided from DPRD at

kabupaten level are not sufficient. Haji Iding suspects

the LPM Chairman is taking advantage of the

development fund. Through the team he formed, Haji

Iding conducted an investigation and found that in

fact, the funds provided were enough to build the

whole village road. Based on this data he then forced

the LPM to continue development without collecting

any further fees from the citizens, and this effort paid

off.

Pemdes is uncomfortable with these criticisms

and attempts to counter them. As in the case of Ucok,

pemdes invites police personnel to block Ucok's

actions. However, in the case of Haji Iding, Pemdes

understands that Haji Iding is an experienced person

in presenting legal cases so that they will not be afraid

of confronting the police. Thus Pemdes make other

efforts such as "black campaign," by continuously tell

about the negative side of Haji Iding.

In Pabuaran, the role of village government is

mostly run by Sekretaris Desa/Sekdes (village

secretary) rather than kepala desa/kades. It seems that

Kades prefers to avoid the criticisms, rarely goes to

the Village Office, and prefer to have an office at

home. Inevitably, this then creates an impression that

she does not want to interact with citizens, does not

represent the aspirations of citizens, and considered

selfish. Residents feel disappointed to have chosen it

for her at Pemilihan Kepala Desa/pilkades

(village

election) two years earlier. According to our

informants, at first, the residents were also doubtful

about her. Approximately 25 years old, she is

considered a junior citizen. Moreover, female kades

is unusual in Pabuaran. She was elected because the

villagers consider his father who was a kades in the

previous period. He did not dare to run again because

the case of his fake elementary school’s certificate

was revealed. At the time of his office, he is very

responsive to the villagers’ aspirations, especially

when it comes to physical infrastructures. Even the

villagers considered him as the most successful

kadesa when he managed to build a village office.

Not interact closely with the residents, Kades

more often approached the government offices in the

district level. This method is considered useful for

obtaining information and access to government aids.

According to her, the more villagers get assistance

with the programs, the more advantage they will be.

She mentioned some of financial assistance that was

obtained from the district, among others, free electric

installation assistance for underprivileged residents,

poor house renovation, and the establishment of some

posyandu (monthly clinic for children and pregnant

women). Her last deal with the district government

that will soon be realized is the distribution of clean

water to villagers’ homes. Kades assumes that by

these efforts, she still cares about the villagers

although she does not always physically present.

2.4 Eligibility and the Emergence of

the Elites

In addition to the effort to win and got prize as a goal,

political competition requires the eligibility of

Social and Political Climbing, Elite Capture, and Democracy in the Current Indonesian Village

351

personnel (Bailey 1969). Not everyone can be

involved in competition, because competition

requires certain requirements. Some components that

can determine eligibility for example are age - related

to seniority, gender, ability or certain qualifications,

ownership of resources, etc. In the political arena in

Pabuaran eligibility is clearly evident in the Ucok and

Haji Iding cases. In this case there is a kind of self-

limitation from citizens to not be included in the

village political arena because there are limitations on

eligibility. They entrust their political aspirations to

the two people.

One of our informants said the reason why he did

not want to be involved in village development

disputes, even though he felt annoyed that he still left

a piece of village road that had not been concreted.

He did not want to complain to the village

government. For him, making a living to meet the

needs of everyday life is more important than

interfering in village development. He works as a

motorcycle taxi everyday. Even though he has a rice

field but the field is limited so that the yield is just

low. According to him, the economic conditions in

Pabuaran are increasingly difficult, the poor are

getting poorer and the rich are getting richer. In this

case, he did not have the qualifications, so he did not

fit to be involved in development.

Examples of cases related to gender feasibility

can be seen in Kiki's story, posyandu cadres who wish

to express their aspirations to the village government

are related to many things: the establishment of less

strategic postal locations, the quarterly salaries that

are not liquid, and the village head's lack of attention

to the cadres. Unfortunately, Kiki felt it was

inappropriate to intervene in the affairs of the village

because she felt she was only a subordinate of the

village head who was also a woman. Therefore, Kiki

prefers to convey her aspirations to the community

head with the hope that he will be conveyed to the

village head.

In addition to qualifications and gender, seniority

can also be used as a reference for someone's

eligibility in competing in an arena. The example is

the story when Haji Iding was immediately appointed

to represent the citizens facing LPM. Haji Iding was

appointed by the residents because he was already

regarded as senior by the people in Kampung

Ciherang Peuntas. In addition to the case of the

village road development, the villagers have been

accustomed to conveying their problems to Haji

Iding.

The development of the Haji Iding qualification

has been going on for quite a long time, which was

around the 1980s when he was still living in Jakarta.

At that time Haji Iding became a spiritual adviser to

the Defense and Security Department. In this position

Haji Iding then had the opportunity to interact directly

with the army on an officer level. This closeness is

used by Haji Iding to explore law: learning court

terms and studying the chapters of the book of

criminal law. This knowledge was then applied by

becoming an unofficial legal adviser to acquaintances

who were involved in matters with the police.

Gradually the news of his expertise arrived at

Pabuaran residents in general and Ciherang Peuntas

Village in particular.

Unlike the senior Haji Iding, Ucok is still young.

He is only around 40 years old. But Ucok has been

trusted by the citizens to solve the problems faced.

Similar to Haji Iding, Ucok has a qualification that is

considered appropriate to enter the village political

arena in Pabuaran. As with Hajj Iding, Ucok's

qualifications are also built from experience.

Regarding the qualification development process,

Ucok said that at the beginning he entered an NGO

where he was trained by his seniors to participate in

critical activities, which forced him to engage in

debate with state officials. For six months as a

volunteer, the Ucok was not accompanied by a

member card, ID, or uniform. Not infrequently he

received resistance from officials whom he criticized.

But this process indirectly made Ucok more skilled in

dealing with state officials.

Surviving as a volunteer, Ucok was later

confirmed as a permanent member. As a permanent

member of Ucok, he was more free to conduct social

criticism on several government institutions

throughout Bogor Regency, including the village

government in Pabuaran. This work is based on the

organization's mandate to oversee the implementation

of the APBD and move according to the public report.

In this position, many cases were handled by Ucok.

The many cases handled by Ucok can be said to

be a process for the development of qualifications in

the political arena. In Pabuaran, several cases were

handled by Ucok. A village officer told us that Ucok

had investigated the involvement of the community

head who allegedly collected fees from residents who

received assistance from the National Disaster

Management Agency (BNPBD) due to a cyclone

disaster. This case had appeared in a local newspaper

report and had also been reported to the police.

Ucok also protested to the Chair of the LPM

because he considered the aid fund for the

construction of uninhabitable houses was cut. Ucok

then reported the Head of LPM to the village head.

The LPM chairman was then called by the village

head and had to clarify his policy to the public.

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

352

4 DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

Referring to Hartmann (2004), elites can be

interpreted as a group of people who emerge from the

masses, small in numbers but can be parties who

govern or regulate the masses because they usually

control some things that are not owned by the masses,

namely material, intellectual, and psychological

capacities. Etymologically, the elite is derived from

French elire, which means "to choose". Based on this

understanding, it can be said that the elite is the

chosen person (Hartmann 2006: 2-19).

In the Pabuaran case, the emergence of the elite is

more by consent (with agreement) than coercive.

Referring to Hartmann's understanding, actually the

elite in Pabuaran were not only Ucok and Haji Iding,

but also village heads. The process of the village head

being an elite is also through agreements such as

Ucok and Haji Iding. The difference is that the village

head becomes an elite because he is elected in formal

elections called Pilkades, while Ucok and Haji Iding

are chosen through informal consensus. Both the

village head, Ucok and Haji Iding, were equally given

the authority by the masses to regulate, in this case

regulating village affairs.

In various studies on community-driven

development, including village studies, elites are

suspected of taking advantage of the development

agenda run by the central government and donors.

The actions of the elites were then interpreted as "elite

capture" (Dutta 2009). Development funds that

should provide benefits to citizens but are captured by

the elites.

Bardhan and Mookherjee (2000) said that elite

capture is always there despite a democratic and

decentralized development process. This

phenomenon according to them needs to be overcome

by approaching the elites so that the delivery process

of development from the center to the regional level

can be carried out properly. Mansuri & Rao (2004)

suggest that the participation process that

accompanies the mechanisms of democracy and

decentralization is dominated by local elites who

generally have a better level of education. This

dominance then led to the management of public

resources to only benefit the elite. According to

Mansuri and Rao, elite capture is still rather difficult

to use as instrument to measure corruption because

there are also benevolent capture, although appear

less then malevolent capture.

However, Dasgupta and Beard (2007) provide

confirmation that elite existence does not always

capture, but there are also those who exercise control.

If elite capture is the practice of elites in utilizing

public resources for their interests, then the elite

control is the practice of elites in controlling public

resources to remain delivered to citizens who are the

target of development. Referring to this study, it

seems that the actions of Ucok and Haji Iding showed

the phenomenon of elite control rather than elite

capture. Ucok and Haji Iding tried to ensure that the

development resources provided by the central

government were truly felt by the villagers.

The separation of capture elites and control elites

as described above is, certainly, only apply to

scientific categorization. In practice there is no strict

separation between the two. Although at a glance the

actions of Haji Iding and Ucok appear to be elite

control rather than capture elites, in practice it is not

possible that there are attempts from both of them to

capture. This cannot be denied because after all the

actions of Haji Iding and Ucok in this context are

included in political actions that are not free from

certain interests or interests. In this thesis, interest or

interest is a form of victory that is to be achieved in

the political actions of citizens.

Our findings indicate that the channeling of

aspirations to specific figures has enabled the

emergence of new elites outside of formal figures

such as village heads, Sekdes, LPM leaders, and so

on. Bailey (1969) states that in order to be able to

compete, one must meet specific criteria or eligibility.

Some indicators that can be used as a reference for

someone eligibility include age, gender, and

qualifications.

The games performed by Kades, Haji Iding, and

Ucok in the political arena in Pabuaran can be

explained by the concept of eligibility. Village heads,

although age and gender are not worth playing in the

arena, but fulfill formal qualifications as Head of the

village in pilkades so that she fulfills eligibility.

Ucok, although regarding age and formal

qualifications appears not eligible, but concerning

qualifications himself has much experience in

advocating citizens. Likewise, Haji Iding, although

already old, but still able to compete in the arena

because of his qualifications as a person who can

solve the problems of citizens through informal ways.

Through this study, we can see the process of

elites' emerging at the local level. Elites can be

interpreted as a group of people emerging from the

crowd, but they can be a party that can govern or

govern because they usually have privilege. Thus the

elite is the chosen person (Hartmann 2006: 2-19). In

the case of Pabuaran, the elite's appearance is more

by consent than coercive. Their status as an elite

through the consent of citizens both formally and

informally.

Social and Political Climbing, Elite Capture, and Democracy in the Current Indonesian Village

353

In community-driven development studies,

including village studies, the elite is suspected to be

taking advantage of development agendas run by

governments and donors. The actions of the elites are

then interpreted as elite capture (Dutta 2009).

Development funds that should benefit citizens are

grabbed by the elite. Mansuri & Rao (2004) suggests

that the process of participation that accompanies

democratic mechanisms and decentralization is

dominated by local elites who generally have better

levels of education. This dominance then causes the

management of public resources to benefit only the

elites. According to them, elite capture is somewhat

challenging to be considered as a corrupt practice

because in elite capture there is benevolent capture in

addition to malevolent capture.

However, Dasgupta and Beard (2007) provide an

assertion that the existence of the elite does not

always do capture, but there is also a control. If the

elite capture is a practice in utilizing public resources

for their benefit, then the elite control is a practice in

controlling public resources to keep delivering to the

targeted citizens. Referring to this study, it seems that

Ucok and Haji Iding's actions are more of an elite

control than elite capture. Both are trying to ensure

that the villagers can enjoy the development resources

provided by the central government. They control

their heads and staff who perform the elite capture.

The village apparatus are suspected of taking

development funds from the central government and

district governments.

The separation of elite capture and elite control as

described above is indeed limited to scientific

categorization. In practice, there is no strict separation

between the two. Although it looks like the elite

control, in practice, there is a possibility that Haji

Iding and Ucok perform the elite capture. As their

actions are filled with political interests, what

performed by Haji Iding and Ucok were undeniably

an elite capture. The other case, when kades, instead

of performing as a leader. In other cases, when kades

do not perform as a leader but a project dealer, she is

doing an elite capture. She tries to get the sympathy

of villagers by ensuring their village get program

assistance from the government. Thus she gets

political legitimacy and may benefit from the

development program in the village.

5 CONCLUSION

The cases of Pabuaran villagers that we presented are

a response to changes in the Village Law and the

implications that some of the requirements of the Act

are not working properly. When the control channel

gets stuck, the villagers look for other figures and

channels to compensate for the behavior of the formal

elite. With his experience as an NGO activist, Ucok

then became the villager's hope to control the

progress of the development program. He entered the

higher stratum as an alternative leader in the village

and became a balancer of formal leaders. Meanwhile,

the senior figure who was originally a religious

figure, with experience dealing with various legal

cases has caused villagers to place him as the

preferred figure to channel their aspirations.

Unlike Mansuri & Rao (2004) which refers to

higher education as a character of the elite, the cases

in Pabuaran show that the experience of the figures is

more important. Education does not always play an

important role although it will not always be the case.

We also find that the process by which actors enter

the political arena in many cases does not mean that

they are conducting formal political actions. In the

case of Haji Iding and Ucok, they are facilitating the

villagers to channel their aspirations; on the other

hand, they are like being in opposition that controls

the formal elite in the village.

REFERENCES

Antlöv, H. 2002. Negara Dalam Desa: Patronase

Kepemimpinan Lokal. (P. Semedi, Trans.) Yogyakarta:

Lappera.

Antlöv, H. 2003. Not Enough Politics! Power, Participation

And The New Democratic Polity In Indonesia. In H.

Antlöv, & G. F. Edward Aspinall (Ed.), Local Power

And Politics In Indonesia. Singapore: Institute of

Southeast Asian Studies.

Antlöv, H. 2003. Village Government and Rural

Development in Indonesia: the New Democratic

Framework. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies,

39(2), 2003.

Antlöv, H., A. W. 2016. Village Governance, Community

Life, and the 2014 Village Law in Indonesia. Bulletin of

Indonesian Economic Studies, 52(2).

Bailey, F. 2001. Stratagems And Spoils: A Social

Anthropology pf Politics. Colorado: Oxford: Westview

Press.

Benda-Beckmann, F. v.-B. 2001. Recreating the Nagari:

Decentralisation in West Sumatra. In Max Planck

Institute For Social Anthropology Working Papers

Series.

Bräuchler, B. 2010. The Revival Dilemma: Reflections on

Human Rights and Self-Determination in Eastern

Indonesia. In Asia Research Institute Working Paper

Series.

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

354

Dasgupta, Aniruddha V. A. 2007. Community Driven

Development, Collective Action and Elite Capture in

Indonesia. Development and Change.

Dutta, D. 2007. Elite Capture and Corruption: Concepts

and Definitions. National Council of Applied Economic

Research.

Have, P. Ten. 2004. Qualitative Methods in Social

Research, Understanding Qualitative Research, and

Methodology. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi:

Sage Publication.

Hüsken, F. (1994). Village Elections in Central Java: State

Control or Local Democracy? (S. C. Hans Antlov, Ed.)

Leadership on Java: Gentle Hints, Authoritarian Rule.

Lucas, A. 2016. Elite Capture and Corruption in two

Villages in Bengkulu Province, Sumatra. Journal Hum

Ecol Interdiscipline, 44, 287-300.

Mansuri, Ghazala V. R. 2004. Community-Based and

Driven Development: A Critical Review. 19(1).

Mattulada. 1986. Demokrasi dalam Tradisi Masyarakat

Indonesia. In A. Rais (Ed.), Demokrasi dan Proses

Politik. Jakarta: LP3ES.

Prijono, Yumiko M. P. 1983. Demokrasi di Pedesaan Jawa.

Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Indonesia.

Rais, A. M. 1986. Demokrasi dan Proses Politik. LP3ES.

Suparlan, P. 1977. Demokrasi dalam Tradisi Masyrakat

Pedesaan Jawa. In A. Rais (Ed.), Demokrasi dan Proses

Politik. Jakarta: LP3ES.

Social and Political Climbing, Elite Capture, and Democracy in the Current Indonesian Village

355