Optimising the Services Capacity Operation with Service Supply

Chain and Option Theories for Elderly Healthcare Systems in China

Jun Zhao and L. K. Chu

Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Systems Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Keywords: Elderly Healthcare Services, Service Supply Chain, Community Governance, Government Purchase of

Services, Option Contract.

Abstract: Traditional elderly healthcare service modes already can hardly meet the rapidly growing demand and high

customer expectations. The community-based elderly service mode (CESM), as a new mode merging with

the advantages of home-based and institution-based elderly service modes, is not yet widely applied in China.

We first analyse the problems of CESM in terms of the government purchase of services (GPS) policy,

governance theories and community elderly services coordination management. Then, we conclude the

research in the fields of the GPS, community governance and service supply chain coordination, and study

the experience of Hong Kong’s community care services system. On the basis, we propose an innovative

structure of community-based elderly healthcare service supply chain (EHSSC), and define the connotation

of EHSSC and its operational processes. Further, we optimise the operational mode for the EHSSC by using

the option contract and service voucher scheme, define the roles and functions of government, community

elderly service integrators, community elderly service providers and the elderly in EHSSC. The operation

processes of community elderly services capacity are illustrated to systematically address the issues of ‘who

participates in’ and ‘how to operate’ in CESM and coordinate the services capacity between the upstream and

downstream. Finally, we put forward some constructive suggestions for the implementation of EHSSC with

the option contract and service vouchers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Aggravated by the increasing demand and higher

customer expectations in China, the community-

based elderly service mode (CESM) has become

popular in China, providing new ideas to meet the

elderly service needs (Lin, 2014). The CESM

originated from the community care mode in the

United Kingdom. As one part of the community

works, the community care mode refers that

professional community workers mobilise

community resources and use formal and informal

support networks to cooperate with governmental and

non-governmental institutions, to help the needy in

the community (Zhang, 2002, Akjiratikarl et al.,

2007). In view of elderly healthcare service systems

in developed countries, China puts forward a brand

new CESM based on the government dominance,

social organizations participation and market

operation, to gradually establish a family-centred and

community-based professional services system to

provide life care, physical care, spiritual consolation,

culture and entertainment for the elderly in the

community. The CESM can not only meet the

elderly’s emotional demand of family attachment

living in their own familiar environment, but also let

them enjoy specialised services in the community,

which effectively integrates the family and society

resources. However, the CESM in China has not

taken satisfactory effects, there are still some issues

needed to be overcome and improved in terms of the

government purchase of services policy, governance

theories and community elderly services coordination

management.

To our knowledge, there is still not a unified

definition of ‘Government Purchase of Services

(GPS)’ in China and abroad (Song, 2013, Petersen et

al., 2015). The means of GPS in China and abroad

mainly include direct procurement, authority to

purchase, contracting out, vouchers, government

subsidies; and different countries may have different

means because of different national circumstances.

Some scholars reviewed the experience of GPS in

China and summarised the main obstacles to the

Zhao, J. and Chu, L.

Optimising the Services Capacity Operation with Service Supply Chain and Option Theories for Elderly Healthcare Systems in China.

DOI: 10.5220/0007249802130220

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES 2019), pages 213-220

ISBN: 978-989-758-352-0

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

213

development of GPS including the poor construction

and organization ability, low efficiency, over-

administration and undeveloped supervision (Nai,

2014). Others put forward different measures to

improve the performance of GPS, such as the

extension of services scope, consideration of service

satisfaction, the elderly’s economic levels, third-party

assessment, trust-building, and independence of

social service organizations (Wen, 2017). Currently,

the implementation of CESM in China is mainly

through direct government purchase of services

(GPS) by which the government pays for some basic

elderly services to meet the community elderly

service demand. Services due to GPS mainly come

from grass-root elderly service organisations, which

are responsible for the final implementation and

delivery. However, the CESM in China has not

achieved the desired effects, major failings, amongst

others, are summarised as follows: (i) Various

government sectors/departments may not (or

incapable of) reach any consensus on the elderly

service demand and functions of community elderly

service organisations; thus resulting in confusion in

policy (Li and Dahl, 2015); (ii) There is not any

specialised and standard legal basis for making GPS,

thus leading to poor GPS decisions or even corruption

(Ramesh et al., 2014, Nai, 2014); and (iii) Those

grass-root service providers often pay lip service to

relevant management advice from government as

formality, and most elderly in communities can

hardly enjoy the benefits from the policy of GPS (Xu,

Wu, and Zeng, 2014). To improve the status quo in

China, we study the case of Hong Kong community

care service system, and analyse the advantages and

disadvantages between the China and Hong Kong

community elderly service systems.

In making GPS by the Chinese government, the

control is mostly responsible by the authority and

authorisations are given to departments

hierarchically. The grass-root community elderly

service institutions or providers are only responsible

for implementation. Such over-administration by the

government undermines the autonomy of community

elderly service institutions (Liu et al., 2008, Wang

and Salamon, 2010). Over time, this results in the

complacency of the service providers, loss of

enthusiasm of the stakeholders (especially the end

users), and the generally low regard and approval

rating of the CESM (Liu, 2006). Therefore, it is

desired that some form of intermediate entity in the

CESM, which can not only share the management

responsibilities with the government, but can also

enhance proactive management awareness and the

efficient use of government resources for elderly

services. We consider the transformation of the

government’s role in the CESM by introducing the

concepts polycentric governance and meta-

governance. Briefly, the proponents of the former

opine that the centre of power to manage the society

is diverse, putting the government, the market and the

society on the same position rather than that

prescribed by the state-centred theory (McKieran et

al, 2000). Polycentric uses cooperation and

consultations to resolve disagreements and conflicts

in the diverse and decentralised social environment.

On the other hand, meta-governance pays more

attention to the role of government in public service

administration (Jessop, 2015). The government still

plays the main role in the case of meta-governance,

and it is regarded as ‘the senior’ in the social

management network. However, the government

does not assume the highest authority but bears the

responsibilities of establishing common guidelines to

govern social organisations and stabilising the

general direction of the main players. For CESM, the

designed way of a governance framework is mainly

based on environmental factors, not least the specific

social and political environments in which it operates

(Meuleman, 2011).

With demand uncertainties due to market

fluctuations or operation changes, the government is

unable to adjust and update the purchasing decisions

in time, resulting in the supply-demand information

asymmetry and waste of community elderly services

capacity (Guo et al., 2013, Nelson and Sen, 2014). In

practice, this operational mechanism is lack of

centralised management as well as the coordination

between the demand and services capacity supply.

The community elderly service institutions have no

rights to supervise the elderly service providers

(ESPs) who cooperate with the government by

contracts, so they cannot directly coordinate price,

costs, service capacity ordering quantity and

relationships. Also, the performance evaluation made

by the elderly for the ESP is not paid attention, so that

the elderly services market is a lack of appropriate

incentives and competition (Yang and Hwang, 2006).

Gradually, the government-led community elderly

institutions lose the risk aversion consciousness.

The tremendous development of the service

industry has motivated the research in service supply

chain (SSC); and the resulting SSC concepts and

theories have been successfully applied to the fields

of logistics, tourism, finance, healthcare (Akkermans

and Vos, 2003; Hong et al, 2011; Huemer, 2012),

amongst others. A more comprehensive definition of

SSC is given by Song and Chen (2009), who describe

SSC as a form of service-oriented integration supply

ICORES 2019 - 8th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

214

chain that, once the downstream customer has

decided on the service demand, the service integrator,

as the core manager, will devise a solution to satisfy

the demand requirements. However, the study in SSC

is still evolving. Few studies have so far sufficiently

elaborated the features of services when developing

the understanding of SSC. Furthermore, the study in

the elderly service supply chain is still nascent. To

address China’s problems of its under-developed

CESM and supply-demand mismatch, there exist

enormous opportunities for exploring the

organisational structure of CESM from the

perspective of SSC. With regard to the coordination

and optimization for the SSC, most scholars have

proved the essence of SSC coordination was the

complementation and cooperation of services

capacity (Anderson and Morrice, 2000). And the

supply contracts are effective tools in SSC, mainly

including the quantity discounts and rebates, option

contract, flexible quantity contract, buyback contract,

compensation contract and so on. Many studies have

illustrated that the option contract could effectively

address the investment and risk-sharing issues on

production capacity as well as the purchase of

services capacity for the service integrator and the

subcontractor. Therefore, this study identifies this

research opportunity and aims at developing a CESM

to address China’s case. The proposed CESM will

embody modern SSC concepts and its coordination

mechanism will base on a set of option contracts.

Based on this research, a set of new methods can be

developed to obtain optimal solutions for elderly

service capacity coordination for the CESM.

2 CASE STUDY OF HONG

KONG’S COMMUNITY CARE

SERVICES SYSTEM

The CESM in Hong Kong is called the ‘community

care services’ (CCS), which is one important part of

Hong Kong’s developed elderly healthcare services

system with outstanding performance. The CCS

system in Hong Kong is more similar to the CESM

promoted in mainland China. Thus, the experience of

Hong Kong’s CCS is more valuable for us to learn.

2.1 Diversified and Integrated

Community Care Services for the

Elderly

The CCS in Hong Kong is mainly classified into two

categories based on the elderly’s physical and mental

status, including the ‘Day Care services for the

Elderly’ and ‘Enhanced Home and Community Care

Services’. The two types of CCS are designed

according to the elderly’s demand with a series of all-

round surveys. And the CCS centre, as the service

manager and implementer, carries out the case

management to track and update the elderly’s

healthcare information. Generally, all the care

services are provided by the third party that are the

non-governmental institutions and non-profit

institutions.

2.2 The Tripartite Cooperation of

Services Supply with Contracts

The supply of community care services capacity has

formed a tripartite cooperation mechanism among the

government, the business and the third party

institutions with contracts. The government refers to

the Hong Kong social welfare department and related

welfare sectors, the business includes the private

service institutions and philanthropists, and the third

party institutions involve the non-governmental

institutions and non-profit institutions.

The government plays the purchase of services,

fund-supporting, policy-making, supervision and

guidance roles in the services capacity supply. The

business works as an indispensable contributor to

make up for the capacity limitations of the

government and non-profit institutions and bring a

huge boost in sponsoring different charity

organizations. The third party institutions are the

executor of policies and services, to some extent

sharing the burden of the government and private

institutions.

2.3 The Pilot Scheme on Community

Care Service Voucher for the

Elderly in Hong Kong

Recently, the mode of community care service

voucher (CCSV) in Hong Kong has aroused

widespread concern (Social Welfare Department of

Hong Kong SAR, 2016b). The pilot scheme on CCSV

for the elderly launched by the Hong Kong Social

Welfare Department in 2013 aimed to provide service

vouchers of about six thousand and five hundred-

dollar monthly value for each elderly with moderately

impaired physical status to subsidise them to freely

select and use suitable care services or service

portfolios. Moreover, the pilot scheme employs the

‘money-follows-the-user’ means, whereby the

government provides subsidy directly to the elderly

(instead of service providers) in the form of service

Optimising the Services Capacity Operation with Service Supply Chain and Option Theories for Elderly Healthcare Systems in China

215

vouchers. Monthly, the government would pay the

ESP for voucher amounts which the ESP receives

from the elderly. During the implementation of the

first-phase CCSV scheme, the performance resulted

well, and now the second phase is in progress.

The CCSV mode is designed to change the

traditional care services capacity operational mode of

‘Government—Care Service Institutions’ into the

customer-centred resource flowing mode of

‘Government—the Elderly—Care Service

Institutions’. It is helpful to promote the public-

private partnership by offering the elderly more

choices of selecting private care services to relieve

pressure on the public care system. Thus, the CCSV

scheme can not only enable the elderly to become

sovereign consumers with government subsidies and

choose care services with freedom, but also stimulate

care institutions to improve their service levels for

competition, contributing to strengthening the

contacts among the elderly and social service

institutions.

2.4 Comparisons and Implications

based on the Practices in China and

Hong Kong

In China, the current services capacity supply and

demand model in the CESM works under an

uncoordinated circumstance without core operators,

where the services capacity flow, information flow

and capital flow can hardly be controlled centrally.

The government works as the policy-maker, capital-

supporter and services buyer, while the community

service institutions mainly serve as the subsidiary of

our government actually without autonomous

operation. Thus, the elderly services capacity

providers work independently for their own profits.

See Figure 1.

However, considering the typical cases of CESM

in China and Hong Kong, we can find that even

though the CESM may be different externally due to

the local governance, they can be mainly classified

into two types based on the means of GPS, in which

one type (Type I) is that the government authorises

the community centres to purchase elderly services

capacity, such as the Beijing Xuanwu District mode,

Nanjing Gulou District mode and Guangzhou Feng

Yuan Street mode (Lin, 2016); the other type (Type

II) is the government directly purchases elderly

services capacity from the ESP, such as the Hefei

mode (Zhao, 2016) and Hong Kong mode (Social

Welfare Department of Hong Kong SAR, 2016a). See

Figure 2.

Figure 1: The current services capacity supply and demand

in China’s CESM.

Figure 2: Two types of CESM based on the GPS modes in

China and Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s CCS system has taken significant

effect on the social welfare (Social Welfare

Department of Hong Kong SAR, 2016a), which is

extremely instructive for the development of CESM

that we are currently implementing in mainland

ICORES 2019 - 8th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

216

China. First, the responsibilities of the core manager

(e.g. the community elderly services centres) in

elderly services should be highlighted with a

dominant role in the execution and coordination of

care services capacity, helping alleviate the

government’s burden. Second, the cooperation

among the government, the community service centre

(i.e. the elderly service integrator, namely ESI) and

the ESP can be reinforced by contracts and

supervision mechanisms. Also, we should encourage

the qualified ESP to participate in community-based

elderly services supply scheme, and introduce

competition mechanism to stimulate the ESP to

improve their service quality and efficiency. Third,

the role of government in elderly services cannot be

ignored, furthermore, we should improve the

government’s abilities on fund-supporting, planning,

supervision and guidance in the whole social elderly

services market, and advocate the government to

purchase elderly services. Finally, it is a creative

measure to offer more rights for the elderly to select

services and to make the elderly as the third party to

help regulate the service provides. However, the

CCSV is now limited to the specific group of aged

people in Hong Kong, and cannot be distributed to all

the elderly as a general welfare. Therefore, it is also

the starting point of this paper to explore how to

overcome the drawbacks of the CCSV mode, perform

the service voucher’s effect of promoting

competition, optimise service capacity allocation and

render the elderly the right to vote for suitable

providers in China.

3 THE OPERATION

MECHANISM OF CESM WITH

THE OPTION CONTRACT

BASED ON THE SSC

3.1 The Innovative Mode of

Community-based Elderly

Healthcare Service Supply Chain

Based on the above theoretical and practical analysis,

we propose a brand new system for the CESM based

on the SSC and governance theories. Zhang et al.

(2011) first studied the elderly service supply chain

(ESSC), and defined it as a type of functional chain

structure, which was oriented towards the

requirements of the elderly. Based on the study,

Zhang et al. (2013) completed a survey and

evaluation about the ESSC’s performance by

applying the ESSC mode into the Guangzhou Feng

Yuan Street community, and they demonstrated its

remarkable effect on improving the CESM. However,

they did not uncover the specific structure of ESSC

and studied further its operation. Considering their

research, we focus on the elderly services in

communities, propose and define that the community-

based elderly healthcare service supply chain

(EHSSC) is a community-centred ESSC in which the

government, the ESP and the elderly service

integrator (the ESI) work collaboratively and

interdependently by a series of contracts to provide

diversified elderly services including physical care,

housekeeping, accommodation, culture, business,

travel, finance and so on, to realize the centralised

management of service flow, capital flow and

information flow.

Figure 3: The mode of community-based EHSSC.

Specifically, the ESI serves as the core institution

in the EHSSC, such as the community elderly service

centre and the community information service centre,

to purchasing the elderly services capacity,

coordinate the supply-demand between the upstream

and the downstream and control the service quality

and risks. The ESPs, including the healthcare

Optimising the Services Capacity Operation with Service Supply Chain and Option Theories for Elderly Healthcare Systems in China

217

institutions, housekeeping services institutions,

accommodation and culture institutions and so on,

directly provide services to the elderly based on the

service solutions made by the ESI. The government

plays an indispensably important role in funding,

supervising the supply chain contracts, promoting

efficient operation and providing related supports.

See Figure 3.

3.2 The Operation Mechanism of

EHSSC with the Option Contract

and Service Vouchers

Considering the drawbacks of CCSV mode, we

design a kind of universal service voucher for all the

elderly in communities, and propose the contract

governance mode aiming to unify the four parties

including the government, the community ESI, the

ESP and the elderly.

Combing the advantages of CESM in China and

Hong Kong, we design a community-based elderly

services capacity operation framework with the

option contract and service vouchers, in which the

option contract is the agreement between the ESI and

the ESP, and the service vouchers are also one kind

of contract between the government and the elderly.

The service vouchers are designed with the

consideration of the elderly’s physical and economic

conditions, and the elderly may afford part of the

services fee by themselves. Thus, the service

vouchers can not only stimulate the elderly to use the

community care services, but also introduce the

competition and voting mechanism.

Figure 4: The operational mode of community-based

elderly services capacity supply-demand.

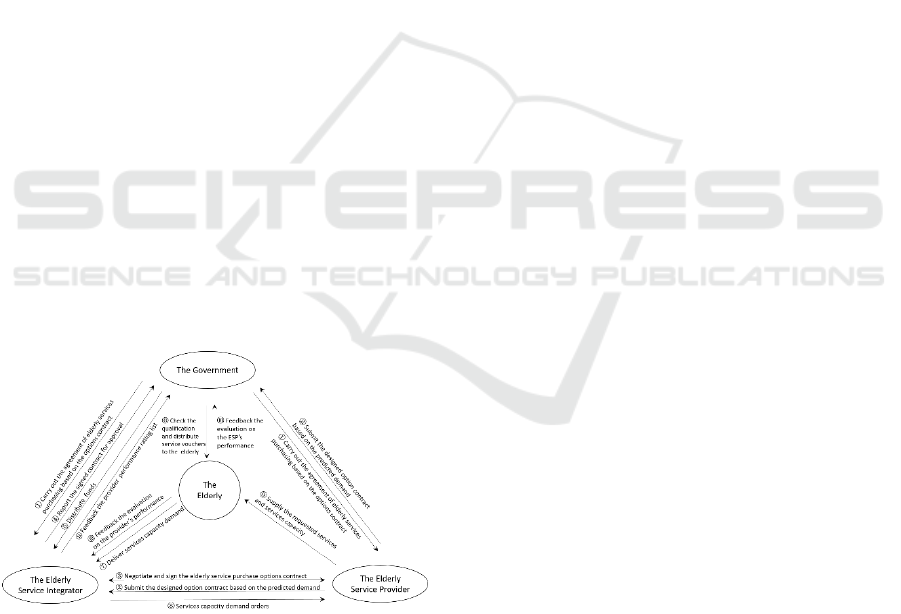

Specifically, the new mode works as follows (see

Figure 4). The government is responsible for

organizing the community ESI and the ESP, and

enacts the negotiation framework of elderly service

capacity option contracts and service voucher

scheme. Then, the ESP submits their service capacity

option contracts to the government and community

ESI. After the first examination and approval by the

government, the community ESI begins to evaluate

the potential ESPs and sign the community-based

elderly service capacity option contracts with the

candidate ESPs. Once the ESP accepts the service

option premium, they should provide requested

elderly services and services capacity with the agreed

price. When the option contract takes effect, the

community ESI would feedback the services capacity

pricing to the government. Then, the government

takes charge of approving and archiving the contracts,

subsequently authorises and funds the ESI to

purchase services capacity and pay related

expenditure. After launching the service voucher

scheme, the government will deliver different valued

service vouchers to the elderly based on the service

capacity pricing and the elderly’s conditions. The

elderly can use the service vouchers to buy favourite

services. Those ESPs, who receive the vouchers, can

redeem equal-valued cash from the government. In

summary, the four parties in the contract governance

mode have the independent operating autonomy,

which means they are interdependent with each other

and share a common interest. All of them have the

resources which are necessary for others to achieve

mutual benefits, but they are also independent to

control the resources, that is, the government holds

the capital, the elderly have the vouchers, the ESPs

have the services capacity, and the ESI has the

responsibilities to coordinate the demand and service

capacity. The participation of four governance parties

in the operational mode promotes the coordination

and cooperation among all stakeholders.

4 SUGGESTIONS ON THE

IMPLEMENTATION OF EHSSC

WITH THE OPTION

CONTRACT AND SERVICE

VOUCHER SCHEME

Thus, it should be a forward-looking method to build

up the CESM with option contract and SSC under the

policy of GPS. There are some suggestions needed to

be adopted to further improve the implementation of

EHSSC with the option contract and service voucher

scheme in practice.

First, it is a must for the government and the ESI

to change their behaviour means in order to

implement the EHSSC with the option contract. With

the transformation of government functions, the

relationships among the government, market and

ICORES 2019 - 8th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

218

society should be reframed objectively. Specifically,

the responsibilities undertaken by the government are

turned over to the community ESI and the ESP in

form of contracts, building up a three-level

cooperation framework within an option contract

system.

Second, it is a need to further improve the

construction of related regulations for the

implementation of EHSSC with the option contract

and service vouchers. The EHSSC with option

contract is a new governance mode to purchase

community-based elderly services capacity and

collaborate the upstream and downstream of SSC,

which is completely different from the traditional

government-led CESM. A new set of regulations and

corresponding measures, undoubtedly are need to be

worked out, such as the specification of funding and

policy support, standards of GPS and rules of

community ESP introduction.

Finally, it is significant to strengthen supervision

for EHSSC. As the executive of the community

elderly services capacity option contract and the core

enterprise in SSC, the community ESI needs to accept

the supervision from the government and the elderly,

in order to ensure the elderly services quality and the

overall interests of the EHSSC. The community ESP,

as the key carrier of the option contract, needs to be

supervised by ESI and the elderly, to unify the overall

goal of EHSSC and facilitate the standard and

sustainable operation.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the current situation and problems on the

CESM, we optimise the CESM systematically from

the perspective of community governance theories,

SSC and option contracts. First, we introduce the

polymeric governance and Meta governance to

reframe and define the relationships and functions

among the government, community ESI and the

elderly. Second, we apply the concept of SSC to put

forward an innovative community elderly services

operation structure——EHSSC, and define the

connotation of EHSSC and its operational processes.

The new mode highlights the core role of ESI, who

strengthens the coordination between the upstream

and downstream, integrates services capacity from

various ESPs, and provides personalized and diverse

service solutions for the elderly. Furthermore, we use

the option contracts and service voucher scheme to

build up the four-dimensional supervision and

cooperation mechanism framework among the

government, the ESI, the ESP and the elderly, and

further propose the operational mode of EHSSC with the

option contract. Finally, we propose some suggestions for

the implementation of EHSSC with the option contract and

service vouchers in terms of the behavioural changes of the

government and ESI, regulations for the EHSSC and its

supervision system, to provide guidance for the

development of EHSSC.

REFERENCES

Akjiratikarl, C., Yenradee, P. and Drake, P. R., 2007. PSO-

based algorithm for home care worker scheduling in the

UK. Computers and Industrial Engineering, 53, 559-

583.

Akkermans, H. and Vos, B., 2003. Amplification in SSCs:

An Exploratory Case Study from the Telecom Industry.

Production and Operations Management, 12, 204-223.

Anderson, E. G. and Morrice, D. J., 2000. A simulation

came for teaching service-oriented supply chain

management: Does information sharing help managers

with service capacity decisions? Production and

Operations Management, 9, 40-55.

Bowles, S. and Gintis, H., 2002. Social Capital and

Community Governance. The Economic Journal, 112,

419-436.

Cai, E., Liu, Y., Jing, Y., Zhang, L., Li, J. and Yin, C., 2017.

Assessing Spatial Accessibility of Public and Private

Residential Aged Care Facilities: A Case Study in

Wuhan, Central China. ISPRS International Journal of

Geo-Information, 6, 304.

Guo, M., Li, B., Zhang, Z., Wu, S. and Song, J., 2013.

Efficiency evaluation for allocating community-based

health services. Computers & Industrial Engineering,

65, 395-401.

Hong, T. K., Zailani S., 2011. SSC Practices from the

Perspective of Malaysian Tourism Industry. In IEEE

International Conference on Industrial Engineering

and Engineering Management (IEEM), 539-543.

Singapore, SINGAPORE: IEEE.

Huemer, L., 2012. Unchained From the Chain: Supply

Management From A Logistics Service Provider

Perspective. Journal of Business Research, 65, 258-

264.

Jessop, B., 2000. The rise of governance and the risk of

failure: A Case Study of economic development, Social

Sciences Academic Press.

Jessop, B., 2015. Governance and Meta Governance: On

Reflexivity, Requisite Variety and Requisite Irony.

Foreign Theoretical Trends, 5, 14-22.

Li, S. and Dahl, J., 2015. Are Chinese Seniors Ready for

Nursing Home Care? [Online]. BEUJING REVIEW.

Available:

http://www.bjreview.com/Nation/201511/t20151102_

800041721.html [Accessed 26 Sep 2018].

Lin, W., 2014. Community service contracting for the

elderly in urban China. Doctor of Philosophy PhD

thesis, City University of Hong Kong.

Lin, W., 2016. Community service contracting for older

Optimising the Services Capacity Operation with Service Supply Chain and Option Theories for Elderly Healthcare Systems in China

219

people in urban China: a case study in Guangdong

Province. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 22,

55-62.

Liu, X., Hotchkiss, D. R. and Bose, S., 2008. The

effectiveness of contracting-out primary health care

services in developing countries: a review of the

evidence. Health Policy and Planning, 23, 1-13.

Liu X. J., 2006. Comparison and Choices of Urban

Community Governance Modes in China. Socialism

Studies, 2, 59-61.

Mckieran, L., Kim, S. and Lasker, R., 2000. Collaboration:

Learning the Basics of Community Governance.

Community, 23-30.

Meuleman, L., 2011. Metagoverning Governance Styles-

Broading Public managers Action Perspective, Jacob

Torfingand Peter Triantafillou. Interactive policy

making Metagovernance and Democracy. Colehester:

ECPR Press, 101-106.

Nai, Y. W., 2014. Several Important Problems of

Government Purchase of Public Services. China

Institutional Reform and Management, 38-41.

Nelson, M. L. and Sen, R., 2014. Business rules

management in healthcare: A lifecycle approach.

Decision Support Systems, 57, 387-394.

Petersen, O. H., Houlberg, K. and Christensen, L. R., 2015.

Contracting Out Local Services: A Tale of Technical

and Social Services. Public Administration Review, 75,

560-570.

Ramesh, M., Wu, X. and He, A. J., 2014. Health

governance and healthcare reforms in China. Health

Policy and Planning, 29, 663-672.

Social Welfare Department of Hong Kong SAR, 2016a.

2016-17 Estimates of Expenditure [Online]. [Accessed

7 Nov. 2016].

Social Welfare Department of Hong Kong SAR, 2016b.

Pilot Scheme on Community Care Service Voucher for

the Elderly [Online]. Hong Kong: Social Welfare

Department of Hong Kong SAR. Available:

http://www.swd.gov.hk/tc/index/site_pubsvc/page_eld

erly/sub_csselderly/id_firstphase/ [Accessed 05

December 2016].

Song, G., 2013. Government Purchase Services:

Mechanism Innovation of the Social Governance.

Journal of Beijing Polytechnic University(Social

Sciences Edition), 10-16.

Song, H. and Chen, J. L., 2009. The Impact of Strategic

Interaction and Value Co-creation to Legitimacy in

SSC. Management Sciences in China, 2-11.

Wang, P. and Salamon, L. M., 2010. Study on government

purchase of public services from social organizations:

lessons from China and abroad, Beijing, Peking

University Press.

Wen, Z., 2017. Government purchase of services in china:

Similar intentions, different policy designs. Public

Administration and Development, 37, 65-78.

Xu S. M., Zhang, J. P., 2014. The Logic and Path of Hub--

type Social Organizations’ Participation in Government

Purchase of Services Contracting --Taking the

Communist Youth League as an Example. Chinese

Public Administration, 9, 41-44.

Yang, W.-S. and Hwang, S.-Y., 2006. A process-mining

framework for the detection of healthcare fraud and

abuse. Expert Systems with Applications, 31, 56-68.

Zhang, X., 2002. Community-based care for the frail

elderly in urban China. Doctor of Philosophy PhD, The

University of Hong Kong.

Zhang, Z. Y., Shi, Y. Q. and Zhao, J. Analysis of the Elderly

Service Supply Chain Management Strategy based on

Service Quality Control and Cooperative Relationship.

COINFO '11, 2011 Hangzhou, China.

Zhang, Z. Y., Zhao, J. and Shi, Y. Q., 2013. Innovation

mode of elderly service supply chain: Performance

evaluation and optimization strategy: An investigation

on liwan district guangzhou city. Commercial Research

(Chinese), 55, 107-115.

Zhao, X. F., 2016. Study on the government purchase of

public service from the social organizations in China

[Online]. Institute of Economic System and

Management National Development and Reform

Commission. Available: http://www.china-

reform.org/?content_501.html [Accessed 05 December

2016].

ICORES 2019 - 8th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

220