Learning with Educational Games: Adapting to Older Adult’s Needs

Louise Sauvé

1

and David Kaufman

2

1

Education Department, Université TÉLUQ / SAVIE, 455, du Parvis, GIK 9H6, Québec (QC), Canada

2

Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, V5A 1S6, Burnaby, (BC), Canada

Keywords: Educational Games, Seniors, Validation, Design.

Abstract: Creating effective online educational games for seniors requires adapting these games to the target players

and their specific educational objectives. To improve seniors’ quality of life with games, we must develop

games that adapt to the cognitive and physical requirements of this audience. Using a user-centered design

methodology, we considered ergonomic criteria (i.e., utility and usability) to design an online educational

game for seniors. This paper presents the variables of the study, the way we adapted the design of the game

Solitaire for older adults, and the results of the field test done with 42 seniors. The participants reported a

high degree of satisfaction with the game's design and demonstrated learning. We present recommendations

to guide the development of online educational games for older adults.

1 INTRODUCTION

What do we know about the ergonomic requirements

for creating effective online educational games to

facilitate lifelong learning for older adults?

Researchers (Diaz-Orueta et al., 2012; Astell, 2013;

Marston, 2013, 2014) have pointed out that the

effectiveness of educational games depends on

players’ needs and individual characteristics and that

we need to develop systems that can adapt to the

demands of the target audience.

An inappropriate design can discourage seniors’

use of online educational games, reducing the

physical, cognitive and social benefits these games

can bring and consequently diminishing older adults’

health and quality of life (Whitlock et al., 2011).

Commercially available games present challenges

in terms of their ease of use for many seniors due to a

lack of knowing their needs (De Schutter and Vanden

Abeele, 2010; Hwang et al., 2011). Given the

importance of a well-constructed educational gaming

interface and the costs involved in its development, it

is important to identify the ergonomic requirements

to be considered during the design process to adapt

the game to older adults’ characteristics and needs.

We view an online educational game as effective

when it meets two quality criteria: it must be useful,

i.e., adapted to its users’ learning objectives and prior

knowledge, and usable, i.e., easy to learn and use.

Although extensive literature has recently been

produced on video game ergonomics and ergonomic

standards (Barlet and Spohn, 2012; Game

Accessibility Guidelines, 2012-2015), it is clear that

these discussions have little or no interest in online

games and even less in games with explicit learning

objectives for older adults.

In this article, we first define what we mean by

ergonomic game design. Then, we describe how we

have adapted the design of a well-known game,

Solitaire, for seniors. We then briefly present the

results of a field test of the educational game, "In

Anticipation of Death", made available online for

testing by 42 seniors to determine their degree of

satisfaction with the game's design and their acquired

knowledge. Finally, in the discussion, we offer

recommendations to guide the development of

effective educational games for older adults.

2 THE NOTION OF

ERGONOMICS

In the development of online educational games, the

ergonomist’s job is to implement solutions to inform

and guide the user in order to reduce as much as

possible the cognitive load of information

(effectiveness) (Millerand and Martial, 2001), while

Sauvé, L. and Kaufman, D.

Learning with Educational Games: Adapting to Older Adult’s Needs.

DOI: 10.5220/0007348002130221

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 213-221

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

213

ensuring that the game is easy to play (comfort), safe

(security) and fun for the player.

Our game development approach is rooted in a

User-Centered Design methodology, which

integrates an ergonomic approach into product

development. This approach is based on criteria of

both utility and usability.

Utility refers to the ability of the game to

facilitate specific learning (meeting defined learning

objectives) for a specific target audience. In other

words, the more meaningful the learning, the more

useful the game.

Usability refers to the ability of the game to

adapt to the characteristics of the target user (user-

centered design) and to be intuitive (user-friendly

and readable). In other words, usability will be high

if a game is stimulating (design) and easy to

understand (navigation and display) so that the

player-game interaction is simple and fluid while

maintaining a sufficient level of difficulty

(challenge / competition) in order to maintain a

satisfying gaming experience (Schell 2010; Dinet

and Bastien, 2011).

In this article, we discuss our adaptation for older

adults of the Solitaire game design and its utility as

measured in a field test.

3 CHOOSING THE TYPE OF

GAME AND ITS

EDUCATIONAL CONTENT

We initially relied on a survey of 931 seniors from

Quebec and British Columbia, as part of the project

"Aging Well: Can Digital Games Help?" (2012-

2016), in which the game of Solitaire was identified

as one of older adults’ favorites (Kaufman et al,

2014).

For the game’s educational theme, we

interviewed 167 seniors aged 55 and over in a

second study, "Promoting Social Connectedness

through Playing Together - Digital Social Games for

Learning and Entertainment" (2015-2020). These

participants were interested in the actions to be taken

upon the death of their spouse; more than 72%

expressed a lack of knowledge about putting the

affairs of their spouse in order, recovering what is

due to their spouse, paying debts and fulfilling their

spouse’s wishes concerning the disposition of their

body (Sauvé et al., 2017).

4 THE OBJECTIVES OF THE

STUDY

The study objectives were: (1) to evaluate the

ergonomic design of the educational game in terms of

its suitability for seniors and (2) to investigate

whether the number of games played with a single

educational game can influence the acquisition of

knowledge that is offered in the game.

In order to meet the objectives of the study, the

interface of the Solitaire game was adapted to allow

us to introduce educational content in the form of

quizzes.

Solitaire is a single-user game that is played with

a deck of 52 cards. The first 28 cards are arranged into

seven columns of increasing size, which form the

Board. Only the last card of each column on the Board

is placed face up. The 24 remaining (face down) cards

make up the Stock pile, also called the Deck. Cards

from the Stock pile are discarded, according to the

player’s choice, one or three at a time (Figure 1).

Design adaptations were made to the interface to meet

the ergonomic requirements of the study, as discussed

below.

Figure 1: Basic Solitaire Interface.

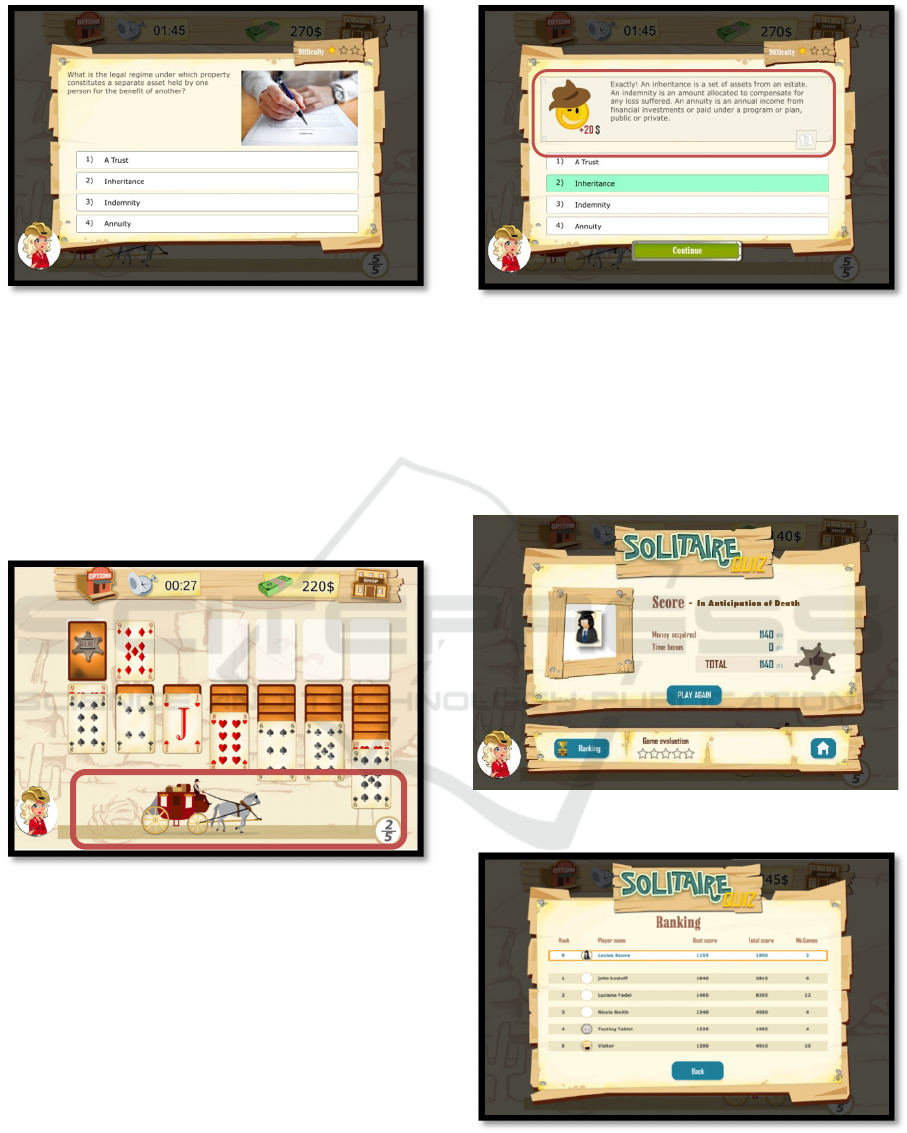

For this study, the Solitaire interface is coupled

with a questionnaire game. At regular intervals,

depending on the number of card displacements, the

player encounters a question. The player’s answer,

right or wrong, affects the player’s accumulated

credits, which correspond to the score and are used

to buy advantages from the online game store. Time

is also important since a bonus or a penalty is given

according to the length of the game.

Finally, the game ends when all the cards are

placed into four places piles for each suit and sorted

in ascending order (from Ace to King), or when a

player declares forfeit because they cannot move

Board

Stock Pile

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

214

any more cards. In the latter case, the player can start

a new game.

5 THE GAME DESIGN FOR

SOLITAIRE

The design of an educational game deals with the

components of the game: gameplay duration,

challenge (game modes, degrees of difficulty, playing

time), score and game materials. It also encompasses

the educational aspects of the game, including how

the learning content and feedback are integrated into

the game (Sauvé 2010, 2017).

5.1 The Game Components

We based our educational game, called Solitaire

Quiz, on Solitaire, which has a short duration to

maintain player motivation and was identified as one

of older adults’ favorites in our initial survey

(Kaufman et al., 2014).

In the "In Anticipation of Death" game, we

incorporated three sets of initial option choices to

vary the sense of challenge: the game mode: turning

over one or three cards (Figure 2); the degree of game

difficulty in relation to the number of credits the

player receives: Easy ($200), Intermediate ($100) or

Difficult ($0) (Figure 3); and playing time to for a

bonus: 0-5 minutes (+$250), 5-10 minutes (+$125) or

10 minutes and more (-$100).

Figure 2: Game Options - Game Mode.

Figure 3: Game Options - Degree of Difficulty.

For scoring related to the movement of cards in

the game, which we found in some online Solitaire

games, we added scoring related to the learning of

educational content. Points either reward or penalize

the player as they respond correctly or not to a

question. The penalty is 50% less than the gain in

order to maintain the player’s interest (Sauvé, 2017),

especially for those who have little knowledge of the

content to be learned.

To augment the game's original materials, we

added privilege cards that a player can buy at any time

if they have enough credits. These privileges allow a

player to finish a game or accumulate money credits;

for example, the Hazardous Freedom card randomly

releases a hidden card from the Board to the Stock

pile.

5.2 The Game Contents

In order to make the game educational, we

incorporated a mechanism to display a question card

(Figure 4) after every five card movements in the

game. If the player answers the question correctly,

they earn points and if they do not answer the question

correctly, they lose points.

For experimental purposes, we split the learning

content into small units, which resulted in 70 closed

questions (true/ false or multiple choice with one or

more answers), divided into three levels of difficulty

(22 easy, 24 medium and 24 difficult) identified by

one, two or three stars. This division ensures that the

questions repeat at least once during a game with the

goal of completing the four piles. Finally, the

questions address the aspects of the will of a person

who dies.

Learning with Educational Games: Adapting to Older Adult’s Needs

215

Figure 4: Displaying a Question.

To ensure a balance between playing and learning,

question cards are displayed after five card

movements. These movements are represented by a

stagecoach that moves on a progression bar, with a

fraction to indicate its progress (Figure 5). The

number of movements needed to display a question

card was determined during the first two tests of the

game (paper and prototype) with older adults.

Figure 5: Movement of the Stagecoach in the Game.

5.3 Feedback

When displaying question cards, we also incorporated

visual feedback on the outcome of the activities in the

form of a smiling or sad face as well as textual and

audible feedback to explain the correct answer

(Figure 6).

As noted above, we added to the game's original

materials, privilege cards that a player can buy at any

time if they have enough credits. These privileges

allow a player to finish a game or accumulate money

credits, for example, the Hazardous Freedom card

which randomly releases a hidden card from the

Tableau to the Stock pile.

Figure 6: Feedback.

Finally, as in other digital Solitaire games, we post

feedback on the player's performance as a score at the

end of the game (Figure 7). This score consists of

money credits earned during the game plus a bonus if

the player has chosen the option of playing with a

time limit.

Figure 7: Ending the Solitaire Game.

Figure 8: Ranking.

In order to motivate seniors to play more often, a

ranking of all players registered for the game is

Feedback

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

216

available at the end of the game by using the Ranking

button (Figure 8).

6 THE METHODOLOGY

In order to assess the design of the educational game

as adapted for seniors 55 and older, we tested the

tablet game on Android and iPad devices with 42

retired older adults.

6.1 The Measuring Instruments

Before the experiment, we administered a

questionnaire on socio-demographic data and

seniors’ habits (12 items) as well as their knowledge

about legal aspects of wills (10 questions). After the

experiment, a self-administered questionnaire on the

game design relating to challenge (six statements),

learning content (three statements) and feedback (five

statements) was given online. The items were

operationalized by a Likert scale of five levels (from

strongly agree to strongly disagree and the option

does not apply). The questionnaire also included a

box to collect written comments from respondents.

We also included 10 questions concerning the

knowledge developed through gameplay and three

items on players’ interest in using educational games

for learning. Finally, we integrated a system to track

players’ responses to the game questions; this is done

for every game in order to measure the degree of

knowledge acquisition by the players during the

experiment.

6.2 The Experiment

The experiment took place over the course of two

months. Participants were invited to play the game at

least five times. This experiment was approved by the

university's ethics committee. Each participant was

made aware of the research purpose and signed a

paper or online consent form.

7 RESULTS

We first describe participants’ demographic data,

followed by an analysis of their participation in

digital games in general. We then present our results

regarding the game design and participant learning.

7.1 Demographic Data

Among the 42 participants in the Solitaire Quiz

experiment, there were 19 women and 23 men. The

sample included 20 participants aged 55 to 60 years

(48%) and 22 subjects aged 61 and over (52%).

Among the sample, nine players said that they did not

have the skills to use digital games, while 18 players

identified themselves as "beginners" and 15 as

"intermediate" participants. Of the 42 participants,

90.5% played the game at least five times for an

average duration of 7.3 minutes, and 42.9% played

between six and nine times for the duration of the

experiment. It should be noted that eight participants

were not included in the analysis because they did not

complete the questionnaires at the scheduled times

(before, during and after the experiment) and three of

them did not play the game five times.

7.2 Participants’ Gaming Habits

Most participants (37 of 42 or 88%) had already

played Solitaire. Some of them (33 of 42 or 78.6%)

had some experience with other digital games: six

players had experience of one year or less, more than

half (19) had between one and five years of

experience, and eight had been playing for more than

six years. Of the 33 players who had some experience

with these type of games, five people (15%) used

them only one day per week. Eleven players (33%)

used digital games two or three days a week, and the

same number of participants played between four and

five days a week, which shows a strong preference

among seniors for the use of technology for

entertainment purposes (66% of participants played

between two and five days per week). Also, of the 33

players who had experience with playing games, 11

played up to 60 minutes a day and, interestingly, 21

people (64%) used them between two and three hours

per day.

7.3 Player Perceptions of the Game

Design

For player perceptions concerning the challenge

presented by the game, all the items had positive

outcomes in that average ratings were are above the

favorable perception threshold (in agreement), that is

to say, 4.00 on all items (Table 1). In addition, the

standard deviations show a low dispersion of

responses, especially when participants commented

on the appropriateness of the game duration (item

QD1), the effect of privileges purchased in the store

for maintain their interest in finishing the game (item

Learning with Educational Games: Adapting to Older Adult’s Needs

217

QD2), and the effect of the scoring system on

motivation (item QD6). In other words, the

respondents' opinions were generally grouped around

the average. The standard deviations of all items are

below 1.00.

Table 1: Perceptions of the Participants of the Challenges

Posed by the Game.

Items Mean SD

Length of Game QD1 4.57 0.91

Privileges and Interest QD2 4.67 0.53

Question Difficulty QD3 4.37 0.89

Limited Time QD4 4.15 0.97

Game Mode QD5 4.34 0.76

System of Points QD6 4.36 0.69

With respect to the game content, participants

expressed a favorable opinion on the elements of this

component (Table 2). The averages of the items

surpassed the threshold of 4.00. In addition, the

standard deviations are below 1.00 in the three Likert

scale items. When asked about the representativeness

of the images in relation to question content (QC9),

the average of this item (4.74) was the highest for the

variable "content of the game" and the standard

deviation (0.50) was the lowest. This supports the

importance of the meaning conveyed by the visual

elements of the game.

With regard to the perception of the

correspondence between prior knowledge and the

accumulation of points (QC7), as well as the

repetition of questions as an effective strategy to

reinforce learning (QC8), respondents showed a very

favorable opinion on these mechanisms for

promoting learning in the game.

Table 2: Participants' Perceptions about Game Content.

Item

Prior

Knowledge

Repetition

of

Questions

Representativeness

of Images

QC7 QC8 QC9

mean 4.55 4.52 4.74

SD 0.67 0.51 0.50

With respect to players’ perceptions about

feedback in the game (Table 3), the average for the

items is very high. Respondents were strongly in

agreement that the feedback for the answers helped

them to progress in the game (item QR10). The

results also show that a smiling or sad face, indicating

whether a question was correctly or incorrectly

answered, conveys the desired meaning (item QR11).

A very favorable perception was also identified in the

QR12 item, which indicated the effect on motivation

of the sound emitted during a good answer. In

addition, respondents strongly agreed that the

automatic audio playback of questions and feedback

facilitates understanding (item QR14). For all these

items, the average was 4.40. Yet, there are some

differences between their standard deviations. In

other words, the dispersion of responses between

these items is variable.

Table 3: Participants' Perceptions about Game Feedback.

Items Mean SD

Game Progression QR 10 4.40 0.63

Smiley Face QR11 4.40 0.59

Sound and Motivation QR12 4.51 0.68

Reinforcing Learning QR13 4.35 0.79

Facilitation of

Understanding

QR14 4.63 0.67

Regarding the learning that was achieved, we

examined the number of questions that were correctly

answered by the players based on the number of times

they played the game (Table 4). The first time the

game was played, respondents answered 24.2% of the

questions correctly. As a result of using the game, the

number of correct answers increased from 24.2% to

88.4% after playing the game for the fifth time,

indicating a progressive learning experience in

relation to the number of times the game was played.

Table 4: Rate of Correct Answers in the Game According

to the Number of Games.

Number

of Respon-

dents

Easy

Questions

Interme-

diate

Questions

Average

Questions 22 6

1st Game 42 31.8% 16.7% 24.2%

2nd Game 42 40.9% 50.0% 45.5%

3rd Game 38 90.9% 83.3% 87.1%

4rd Game 38 91.2% 83.9% 87.5%

5rd Game 37 92.2% 84.6% 88.4%

In addition, the vast majority (92.86%) of the

participants liked to play Solitaire enhanced with a

Quiz (item QI1) and 90.48% of the players wished

they could try a new quiz (item QI2). All participants

would recommend the game to others (item QI3)

(Table 5).

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

218

Table 5: Interests of Participants.

Desire for

Playing

Solitaire

Quiz

Interest

in Trying

New

Quizzes

Would

Recommend the

Game to Others

QI1 QI2 QI3

Yes

39 38 42

92.86% 90.48% 100.00%

No

3 4 0

7.14% 9.52% 0.00%

7.4 Modulation of Responses on the

Ergonomics of the Game

Differences in perceptions by age group (under 60

and 61 or over), gender, computer skills (beginner,

intermediate, expert) and skill level as an online

player (beginner and intermediate) were all examined

with the Student t-test with a bilateral distribution of

unequal variance with two examples

(heteroscedastic). A difference was considered

statistically significant when the associated p value

was less than or equal to 0.05.

These results indicate that the level of ability in

using digital games modulates perceptions in terms of

feedback, especially for beginners. For the aspects of

challenge and content, the age and gender criteria,

and computer skills give substantially the same

results, that is, the differences are negligible.

8 DISCUSSION

Our results confirm the importance of offering games

of short duration to maintain seniors’ motivation,

while integrating allowing players to vary the

duration of the game (Whitlock et al., 2011;

Kickmeier-Rust et al., 2012; Shang-Ti et al., 2012;

Theng et al., 2012; Sauvé et al., 2015; Sauvé 2017).

In terms of the challenges the game brings, the

addition of new elements to the game, including

privileges that can be purchased in the game store,

have helped to maintain players’ interest in finishing

the game. This is consistent with the findings of Al

Mahmud et al. (2012) as well as Mubin et al. (2008),

who suggest incorporating new rules (add-ons) to

maintain a sense of challenge in known games.

Seniors prefer to play games that they know, with

add-ons that engage them.

These results show that players place a high value

on the degree of difficulty of the questions

(represented by ★★ ☆ icons) in relation to the

challenge they pose. Similarly, Lavender (2008),

De Schutter (2010) and Sauvé (2010) note the

importance of how the learning content is treated

(from simple to complex) in the game in order to

offer multiple degrees of difficulties. Marston and

Smith (2012), Shang-Ti et al. (2012) and Sauvé

(2017) recommend that players be informed that the

easy level corresponds to the basic knowledge of the

players, thus encouraging everyone to participate.

Participants confirmed that the option of

"Playing with a time limit”, to gain additional

points, was a motivating challenge. The availability

of two game modes (one-card or three-card) also

represented different challenges in the game,

according to the players' responses. The in-game

scoring system was seen as an additional source of

motivation. These facts align with the findings of

several studies (Sauvé 2010; Rice et al., 2011; Diaz-

Orueta et al., 2012; Senger et al., 2012; Sauvé et al.,

2015) whereby one should incorporate different

difficulty levels or challenges to the user to foster

competition, facilitate learning, build self-

confidence and concentration, and better engage

older adults in the game.

Relative to game content, using closed questions

facilitates the use of prior knowledge in order to

accumulate points and progress in the game. In two

previous studies (Sauvé et al., 2015; Sauvé 2017), we

concluded that it is crucial to analyze the learning

content and to break it down into small units of

information; this makes it possible to formulate

simple questions in order to avoid cognitive overload

in seniors. These findings were verified by the results

of this study.

Players emphasized the importance of question

repetition for reinforcing learning. Indeed, limiting

the number of learning activities in a game allows

seniors to recognize them and consider them useful

for their progression in the game (Sauvé 2010; Sauvé

et al., 2015). The results also reveal that it is important

to ensure the representativeness of images used in the

questions (Lopez-Martinez et al., 2011; Shang-Ti et

al., 2012; Sauvé et al., 2015).

Breaking up the learning content is of primary

importance in order to balance learning time and

playing time (Sauvé 2010) so that not all game

activities require learning success. In a previous study

(Sauvé 2017), we recommended leaving room for

actions related to the pleasure of playing. In this

sense, participants emphasized the fact that Solitaire

Quiz is an original way to learn more about certain

topics.

Learning with Educational Games: Adapting to Older Adult’s Needs

219

The players in this study highlighted the

usefulness of question feedback for progressing in the

game. This agrees with observations of Sauvé (2010),

Callari et al. (2012), Gerling et al. (2011) and Sauvé

(2017) who emphasize the importance of integrating

mechanisms that reinforce the results of learning

activities with visual or audible feedback. For

example, seniors who participated in our study

commented that the face that accompanied each

feedback comment, and the sound emitted for a

correct response, made it easy to quickly identify

whether the question was answered correctly or not.

This is consistent with the results of Lopez-Martinez

et al. (2011), Marston and Smith (2012), Senger et al.

(2012) and Wu et al. (2012).

Finally, the results show that seniors achieved a

significant amount of learning from the use of the

game, while also having the pleasure of playing.

9 CONCLUSIONS

Although the perceptions observed in this study relate

to a specific game (Solitaire Quiz), the results can be

applied to different types of games. Our study shows

that in order to make an educational game easier to

use by seniors, it is important to provide an

appropriate level of difficulty and be adapted for this

audience. It is important to reduce the risk of

frustration by proposing an interesting challenge.

The results of this study suggest several aspects to

consider, such as an appropriate game duration, a

clear way to finish the game, displaying game

progression and the graphical representation of the

level of difficulty of the questions related to lifelong

learning.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

These two research studies were funded in part by

grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities

Research Council of Canada and from AGE-WELL

NCE, Inc., a member of the Networks of Centres of

Excellence of Canada. We would like to thank

Gustavo Adolfo Angulo Mendoza for the statistical

analysis of the data of the study, Curt Ian Wright for

the translation and Alice Ireland for the revision. We

would also like to thank the development team, Pierre

Olivier Dionne, Jean-Francois Pare and Louis

Poulette, for the online educational game.

REFERENCES

Al Mahmud, A., Shahid, S., Mubin, O., 2012. Designing

with and for older adults: experience from game design.

In Human-Computer Interaction: The Agency

Perspective (pp. 111-129). Springer Berlin Heidelberg,

Berlin.

Astell, A.J., 2013. Technology and fun for a happy old age.

In A. Sixsmith and G. Gutman (eds.), Technologies for

Active Aging (pp. 169-187). Springer, New York.

Barlet, M. C., Spohn, S. D., 2012. Includification: A

practical guide to game accessibility. The Ablegamers

Foundation, Charles Town. http://www.includification.

com/AbleGamers_Includification.pdf.

Callari, T. C., Ciairano, S., Re, A., 2012. Elderly-

technology interaction: accessibility and acceptability

of technological devices promoting motor and

cognitive training. Work, 41(Supplement 1),

pp. 362-369.

De Schutter, B., 2010. Never too old to play: The appeal of

digital games to an older audience. Games and Culture,

(62), pp.155-170.

De Schutter, R., Vanden Abeele V., 2010. Designing

meaningful within the psycho-social context of older

adults. In V. V. Abeele, B. Zaman, M. Obrist, W.

IJsselsteijn (eds.), Fun and Games 2010: Proceedings

of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games

(pp. 84-93). ACM, New York, NY, September.

Diaz-Orueta, U., Facal, D., Herman Nap, H., Ranga, M.-M.,

2012. What is the key for older people to show interest

in playing digital learning games? Initial qualitative

findings from the LEAGE Project on a Multicultural

European Sample. Games for Health, 1(2), pp. 115-

123.

Dinet, J., Bastien, C., 2011. L’ergonomie des objets et des

environnements physiques et numériques [The

ergonomics of objects and of physical and digital

environments]. Lavoisier, Hermès, Paris.

Game accessibility Guidelines, 2012-2015. Game

accessibility guidelines. Full list. http://game

accessibility guidelines.com/full-list.

Gerling, K. M., Schulte, F. P., Masuch, M., 2011.

Designing and evaluating digital games for frail elderly

persons. In Proceedings of the 8th International

Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment

Technology (pp. 62). ACM, November.

Hwang, M. Y., Hong, J. C., Hao, Y. W., Jong, J. T., 2011.

Elders' usability, dependability, and flow experiences

on embodied interactive video games. Educational

Gerontology, 37(8), pp. 715-731.

Kaufman D, Sauvé L, Renaud L, Duplàa E., 2014. Enquête

auprès des aînés canadiens sur les bénéfiques que les

jeux numériques ou non leur apportent [Survey of

Canadian seniors to determine the benefits derived from

digital games]. Research report, TELUQ, UQAM,

Quebec, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver (BC),

University of Ottawa, Ottawa.

Kickmeier-Rust, M., Holzinger, A., Albert, D., 2012.

Fighting physical and mental decline of the elderly with

adaptive serious games. In P. Felicia (ed), Proceedings

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

220

of the 6

th

European Conference on Games Based

Learning (pp. 631-634). Conferences international

Limited, October 4-5.

Lavender, T. J., 2008. Homeless: It’s no game – Measuring

the effectiveness of a persuasive videogame.

Unpublished Master's thesis. School of Interactive Arts

and Technology. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver

(BC).

López-Martínez, Á., Santiago-Ramajo, S., Caracuel, A.,

Valls-Serrano, C., Hornos, M. J., Rodríguez-Fórtiz, M.

J., 2011. Game of gifts purchase: Computer-based

training of executive functions for the elderly. In 1st

International Conference on Serious Games and

Applications for Health (SeGAH), (pp.16-18). IEEE

Computer Society, Washington, November. doi:

10.1109/SeGAH.2011. 6165448

Marston, H.R., Smith, S.T., 2012. Interactive videogame

technologies to support independence in the elderly. A

narrative review. Games for Health Journal, 1/2, pp.

139-152. doi:10.1089/g4h.2011.0008

Marston, H. R., 2013. Design recommendations for digital

game design within an ageing society. Educational

Gerontology, 39(2), pp. 103-118. doi:10.1080/036012

77.2012.689936

Marston, H. R., 2014. The future of technology use in the

fields of gerontology and gaming. Generations Review,

24(2), pp. 8-14.

Millerand, F., Martial O. (2001) Guide pratique de

conception et d'évaluation ergonomique de sites Web

[Practical guide for designing and evaluating websites

ergonomically]. Centre de recherche informatique de

Montréal, Montréal. http://fse.blogs.usj.edu.lb/wp-

content/blogs.dir/31/files/2011/08/CRIM-Guide-

ergonomique.pdf

Mubin, O., Shahid, S., Al Mahmud, A., 2008. Walk 2 Win:

Towards designing a mobile game for elderly's social

engagement. In D. England (ed), Proceedings of the

22nd British HCI Group Annual Conference on People

and Computers: Culture, Creativity, Interaction-

Volume 2 (pp. 11-14). BCS Learning & Development

Ltd, Swindon, Royaume-Uni, September 1-5.

Rice, M., Wan, M., Foo, M. H., Ng, J., Wai, Z., Kwok, J.,

Lee, D., Teo, L., 2011. Evaluating gesture-based games

with older adults on a large screen display. In TL Taylor

(ed), Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGGRAPH

Symposium on Video Games (pp. 17-24). ACM,

Vancouver, BC, August 7-11.

Sauvé, L., 2010. Les jeux éducatifs efficaces [Effective

educational games]. In L. Sauvé and D. Kaufman

(eds.), Jeux et simulations éducatifs : Études de cas et

leçons apprises [Educational games and simulations:

Case studies and lessons learned] (pp. 43- 72). Presses

de l’Université du Québec, Saint-Foy, Québec.

Sauvé, L., Renaud, L., Kaufman, D., Duplàa, E., 2015.

A digital educational game for older adults: “Live Well,

Live Healthy!”. In 9th International Technology,

Education and Development Conference - INTED2015

Proceedings (pp. 842-851). Madrid, Espagne, March 2-

4.

Sauvé, L. 2017. Online educational games: Guidelines for

intergenerational use. In M Romero, K. Sawchuk, J.

Blat, S. Sayago and H. Ouellet (eds.), Game-Based

Learning across the Lifespan. Cross-generational and

age-oriented digital game-based learning from

childhood to older adulthood (pp. 29-45). Springer

International Publishing Switzerland, Switzerland.

Sauvé, L., Plante, P., Mendoza, G.A.A., Parent, E.,

Kaufman, D., 2017. Validation de l’ergonomie du jeu

Solitaire Quiz: une approche centrée sur l’utilisateur

[Validation of the ergonomics of the game Solitaire

Quiz: A user-centered approach]. Research Report,

TÉLUQ, Quebec, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver

(BC).

Schell, J., 2010. L’art du Game design: 100 objectifs pour

mieux concevoir vos jeux [The art of game design: 100

objectives for creating better games]. Pearson

Éducation France, Paris,

Senger, J., Walisch, T., John, M., Wang, H., Belbachir, A.,

Kohn, B., Smurawski, A., Lubben, R.-Z., Jones, G.,

2012. Serious gaming: Enhancing the quality of life

among the elderly through play with the multimedia

platform SilverGame. In R. Wichert and B. Eberhardt

(eds.), Ambient Assisted Living (pp. 317-331), Springer,

Berlin Heidelberg.

Shang-Ti, C., Huang, Y. G., Chiang, I. T., 2012. Using

somatosensory video games to promote quality of life

for the elderly with disabilities. In IEEE Fourth

International Conference on the Digital Game and

Intelligent Toy Enhanced Learning (DIGITEL) (pp.

258-262). IEEE, Takamatsu, Japon, March. doi:

10.1109/DIGITEL. 2012.68

Theng, Y. L., Chua, P. H., Pham, T. P., 2012. Wii as

entertainment and socialization aids for mental and

social health of the elderly. In CHI'12 Extended

Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing

Systems (pp. 691-702). ACM, Austin, Texas, May 5-10.

doi:10.1145/2212776. 2212840

Whitlock, L. A., McLaughlin, A. C., Allaire, J.C.,

2011, Video game design for older adults: Usability

observations from an intervention study. In

Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics

Society Annual Meeting, 55(1), 187-191. September.

doi:10.1177/1071181311551039

Wu, Q., Miao, C., Tao, X., Helander, M. G., 2012. A

curious companion for elderly gamers. In Network of

Ergonomics Societies Conference (SEANES), 2012

Southeast Asian (pp. 1-5). IEEE, Langkawi, Kedah,

Malaysia, July. doi: 10.1109 / SEANES.2012.6299597.

Learning with Educational Games: Adapting to Older Adult’s Needs

221