Towards Aligning GDPR Compliance with Software Development:

A Research Agenda

Meiko Jensen

1

, Sahil Kapila

1

and Nils Gruschka

2

1

Kiel University of Applied Sciences, Kiel, Germany

2

University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Keywords:

GDPR, DPIA, Data Protection Impact Assessments, Privacy.

Abstract:

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) caused several new legal requirements software systems in

Europe have to comply to. Support for these requirements given by proprietary software systems is limited.

Here, an integrative approach of combining software development with GDPR-specific demands is necessary.

In this paper, we outline such an approach on the level of software source code. We illustrate how to annotate

data in complex software systems and how to use such annotations for task like data visualization, data ex-

change standardization, and GDPR-specific consent and purpose management systems. Thereby, we outline a

research agenda for subsequent efforts in aligning software development and GDPR requirements.

1 INTRODUCTION

The advent of the new European General Data Pro-

tection Regulation (GDPR, (European Parliament and

Council, 2016)) has led to multiple new legal require-

ments for organizations operating in Europe and be-

yond. It demands for precise information concerning

all data processing of personal data happening within

organizations, along with their purposes and specific

conditions. This demand currently causes a lot of

challenges with organizations that struggle with the

challenging task of gathering the required informa-

tion from their own software systems. Most propri-

etary software today does not offer any insights into

how it processes data, which of that data is of per-

sonal or even sensitive nature w.r.t. the GDPR, and

how that data passes through the processing systems

implemented.

In this paper, we envision a software development

approach that incorporates GDPR-based demands at

the very early software development stages. The aim

being to bolster the compliance process and hasten in-

dustry alignment with the current state of the GDPR.

We illustrate the different ways a GDPR-supportive

software development approach may be implemented

and utilized. We also briefly discuss some approaches

on how to mine processes for GDPR-relevant in-

formation, how to support the creation of GDPR-

demanded documentation of processing of personal

data at the software development level, and we high-

light some subsequent concepts for visualizations,

tools and exchange standards to ease the work with

and exchange of GDPR-relevant information among

stakeholders. Altogether, we therefore outline a re-

search agenda on how to align the task of software

development with the specific needs caused by the

GDPR.

The paper is organized as follows: The next sec-

tion defines some of the important concepts and terms

of the GDPR, necessary to understand the subsequent

sections. Then, Section 3 debates issues of implemen-

tation of the GDPR and the impacts on software de-

velopment. Section 4 then introduces our approach

of data annotations at source code level, which is dis-

cussed in terms of visualizations in Section 5 and in

terms of standardization, integration and management

in Section 6. The paper concludes in Section 7.

2 GDPR BASICS

The GDPR defines several terms and concepts nec-

essary for understanding the remainder of this paper.

The reader familiar with the GDPR terminology may

skip this section.

A data subject in GDPR terms refers to the hu-

man individual whose data is processed within a data

processing system (e.g. a software implementation).

The data controller is the organization (or the mul-

Jensen, M., Kapila, S. and Gruschka, N.

Towards Aligning GDPR Compliance with Software Development: A Research Agenda.

DOI: 10.5220/0007383803890396

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2019), pages 389-396

ISBN: 978-989-758-359-9

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

389

tiple organizations, in case of a joint controllership,

cf. (European Parliament and Council, 2016, Article

26)) that decides how the data processing system is

designed, what data types are collected from the data

subject, how that data is processed, and what other

organizations (data processors) may be hired to par-

ticipate in this processing. In order to legally collect

data from the data subject, the most commonly used

approach in private sector industries consists in the

consent: a data subject is asked to explicitly allow

for data processing of a certain type for a certain pur-

pose. That data may then not be used for other pur-

poses than those the data subject has consented to (un-

less some exceptional conditions apply, cf. (European

Parliament and Council, 2016, Articles 8 and 10)). A

data subject may withdraw consent of data process-

ing, in whole or in part, e.g. just for some purposes or

for some data types, at any time, resulting in the data

controller(s) having to cancel processing of that data

as soon as possible.

Data according to the GDPR is effectively catego-

rized in three relevant groups:

Non-personal data is not directly linkable to a per-

son, and hence can be processed arbitrarily,

Personal data is somewhat directly linkable to a per-

son, and hence must be processed in accordance

with the regulation’s articles, and

Sensitive personal data is typically directly linkable

to a person and poses a severe threat to that person

if the data is lost or misused. Such data may only

be processed under specific conditions, utilizing

advanced precautions and protection mechanisms

(cf (European Parliament and Council, 2016, Ar-

ticle 9)).

One of the major requirements posed in the GDPR

is that of performing a data protection impact assess-

ment (DPIA, cf. (European Parliament and Council,

2016, Article 35)). The task here is to identify, list,

and handle all potential risks to privacy and data pro-

tection that may be caused by the processing of per-

sonal data of a data subject at a data controller or

data processor. Obviously, this task requires exact in-

formation concerning what data is processed in what

places and for which purposes at which organizations

participating in a data processing system.

3 THE GDPR LANDSCAPE

In order to comply with the 99 articles of the GDPR,

it becomes necessary to extract and document a large

array of information concerning one’s data process-

ing operations, such as purposes and legal grounds for

processing of personal data. In this effort, many com-

panies and government institutions face a dilemma:

though the text of the new regulation is public for

more than two years, it is still not clear how it will

be enforced in real-world scenarios. Here, the ma-

jor data protection authorities in Europe still need to

provide more precise details as to how its paragraphs

will be enforced. For organizations, this means that

they can not easily determine which tasks they need

to perform in order to comply, and which tasks may

be optional.

However, it is already evident that the major focus

of the GDPR and its enforcement concerns process-

ing of personal data, which is also labeled as per-

sonally identifiable information (pii, (Schwartz and

Solove, 2011)) in the literature. Hence, it can already

be seen that the data collected, stored, processed, for-

warded or otherwise dealt with within the processes

running inside an organization are of eminent impor-

tance when it comes to GDPR compliance check-

ing. At the same time, tools and techniques to ex-

tract and visualize the flow of data within processes

typically do not focus on GDPR relevance of the data

flows. Though multiple data and process modeling

standards exist (such as UML (Object Management

Group, 2015) or BPMN (Object Management Group,

2014)), few of them provide explicit support for secu-

rity or privacy assessments as required by the GDPR.

Here, a demand for GDPR-specific tools for pro-

cess mining, visualization, and documentation, with

a strong focus on processing of personal data within

these processes and linked to the GDPR requirements

became evident.

4 DATA ANNOTATIONS

The most important task to solve when it comes to

validating GDPR compliance of a complex, inter-

organizational data processing system consists in

elaborating the set of personal data that is actually

processed within an organization. Only data that is

actually processed is in scope for the GDPR, and only

if it is of personal nature. Here, many organizations

face the struggle to determine which data they actu-

ally process, in which processes that data is actually

processed, and which of the data is of personal or even

sensitive personal nature.

To overcome this shortage, a set of techniques

have already been developed in research to extract

data and data flows from existing process models,

source code, log files, or even full-text documentation

reports (cf. (Accorsi and Stocker, 2012; Van der Aalst,

2016; Accorsi et al., 2011; Valdman, 2001; Sharir and

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

390

Pnueli, 1978; De and Le M

´

etayer, 2016)). However,

none of these approaches is immediately suited for

dealing with GDPR compliance. Especially the char-

acterization of data being personal has not yet been

incorporated into any of these efforts. This also stems

from the fact that this characterization itself is a chal-

lenging one, as will be explained next.

4.1 The Problem of Determining

Sensitivity of Personal Data

Imagine a system that utilizes a customer’s name

and taxation ID (where we assume the latter to be a

government-issued, unique identifier of each citizen,

such as the Danish CPR numbers (Pedersen et al.,

2006)). Both data items clearly are of personal na-

ture, as both serve to identify the person behind the

data easily. Intuitively, the taxation ID is even “more

personal” than the name, as it uniquely identifies ex-

actly one human being, whereas a name (as a string

of characters) could be shared by many individuals of

the same name, and therefore is not unique.

Without a doubt, the taxation ID is also a sensitive

personal information. When knowing the taxation ID

of an individual, it is possible to find out some addi-

tional information concerning the individual, such as

its financial situation (based on tax reports), its prob-

able age (the Danish CPR is based on the birthdate)

and gender (coded into the Danish CPR again). Out

of these, the financial situation can clearly be misused

to harm an individual to the point of social ostracism,

therefore it clearly fulfils the definition of a sensitive

personal data item as defined in Article 9 GDPR.

The sensitive nature of the name is not that obvi-

ous, and many lawyers and data protection activists

will argue that a name is not a sensitive personal in-

formation. First, it is typically not directly possible to

gather critical, harmful information from a person’s

name. Second, a name is publicly used to identify a

person in society, therefore it is not considered a “se-

cret” in any context. Nevertheless, a name contain-

ing “Muhammad” can directly be linked to a religious

background, with a high probability of the person (or

its parents) following a certain religion. Therefore,

it may count as a sensitive information itself as well.

From this example another fact becomes apparent, a

determination of sensitivity would require a call to

be placed on evaluating multiple dimensions such as

usage of the data, inheritance from parent data types

(if applicable), context, level of anonymization and/or

generalization, among others. However, for the sake

of this example, we will treat a name as non-sensitive

personal data from now on.

4.2 The Problem of Determining the

Status of Derived Data

If we now assume that a software system collects and

stores both these data items, name and taxation ID, for

every customer, we already have identified two possi-

ble sources of risks to a customer’s privacy (if the data

gets lost) and two objects of interest when implement-

ing a customer’s data access rights (cf. (European Par-

liament and Council, 2016, Article 15)). Thus, in-

formation concerning these data items and their pro-

cessing is of clear interest to anyone trying to validate

GDPR compliance for the system in consideration.

Now let’s assume the system utilizes both data

items in combination to generate a unique identifier

per customer, for use as a unique yet speaking refer-

ence for subsequent processes

1

. Here, the system uti-

lizes both name and taxation ID as input to generate a

new data type: a customer ID. This new data item is

thus derived from the two inputs of name and taxation

ID, and thus may inherit the values and some of the

properties associated with these inputs. Especially, it

obviously is personal data itself again. This is due to

the fact that both the inputs were personal data, the

resulting data item is used for identification of human

individuals (here: customers), and the processing of

these inputs did not include any sort of anonymiza-

tion techniques. Both input data are clearly visible

and extractable from the newly generated data item of

customer ID. Hence, it is easy to see the inheritance

of this property to the “child” data item born from the

two previous ones.

A more complex question is whether the result-

ing customer ID also is a sensitive personal data item.

One of the inputs was sensitive, whereas the other was

not (see discussion above). Hence, the decision of

whether the resulting item is of sensitive personal na-

ture or not depends on the type of processing. Here,

a major challenge lies in the determination as to what

extent the sensitivity of the input data items is trans-

ferred to the newly created data item. If the customer

ID contains the complete taxation ID verbatim, that

latter can easily be extracted from the former, and

therefore the customer ID can easily be linked to a

customer’s taxation data and financial situation, ren-

dering it a sensitive personal data item. If only part of

the taxation ID is used in the customer ID, or if some

other method of anonymization or pseudonymization

is applied (such as hashing of inputs or generaliza-

tion of data, see e.g. (Zhou et al., 2008; Pfitzmann

and Hansen, 2010)), the resulting customer ID may

1

We omit the debate on whether this is a reasonable way

to create a customer identifier in the light of the GDPR here.

In short: it is not!

Towards Aligning GDPR Compliance with Software Development: A Research Agenda

391

Figure 1: Example of data annotations in a common IDE.

not that easily be linkable to the taxation context of a

customer, and thus the status of sensitivity of the new

data item is different. To subsume, the sensitivity sta-

tus of the derived data items depends on the sensitivity

status of the input data items and the type of process-

ing applied to the newly created data item.

The same holds true for the status of “personal”:

if one input is of personal nature and another input

is not personal, the result may be personal or non-

personal, depending on the processing. However, if

none of the inputs is personal, newly generated data

items will never be personal themselves. Similarly,

if none of the inputs is of sensitive nature, the newly

created data items will not be of sensitive nature them-

selves as well.

4.3 Annotating the Status to the Data

As can be seen, it is of eminent importance to deter-

mine and trace the status of “personal” and “sensitive”

data items throughout the processing of data within

a complex software system. Hence, it is necessary

to document the assumed status of each and every

data item utilized within a processing environment.

This information can be documented in multiple dif-

ferent ways when dealing with real-world process de-

velopment scenarios. For instance, the relevant data

items could be collected in a separate, hand-written

text document, explaining the data item, its status and

assumed conditions. However, this approach is error-

prone and complex, and does not allow for subsequent

automated processing of that list itself. Thus, we pro-

pose a different approach: to annotate the GDPR-

relevant information (like personal/sensitive status)

directly to the data item in question within the source

code of the processing software itself. Similar to the

commonly used frameworks for automation of source

code documentation (e.g. JavaDoc (Oracle Inc., 2004;

Kramer, 1999)), we suggest to define source code

level annotations to data items that can be used to im-

mediately define the assume status of data items uti-

lized within the source code.

An example is shown in Figure 1. As can be

seen, the method getCustomerID uses the two in-

puts of name and taxID to create the new data item

of CustomerID. Thus, we have two inputs and one

output. Using the annotations seen above the code it-

self, a programmer can now directly annotate the sta-

tus of the inputs and also declare the name and status

of the newly created data item of CustomerID. These

annotations, which follow the common approach for

source code annotations for other purposes, can then

be used by subsequent source code evaluation tools

for subsequent uses (see next section).

As can be seen from the example, this annotation

approach in our test environment already supports the

use of the following annotation tags:

Data allows for annotating an input data item (that

must be named equal to the corresponding vari-

able name) with its status of being personal or

even sensitive.

dataCreated defines the newly created data items

from this method invocation. This may be the re-

turned result value (as shown in the figure), but

may also be any other data item that is newly cre-

ated within the code of the method invocation, e.g.

if it is added to some exteral database or sent to

some other software component within the source

code. As with the input data, the programmer can

directly utilize this tag to annotate the assumed

status of these newly created data items w.r.t. per-

sonal or sensitive status.

Purpose is a free-text field allowing to briefly de-

scribe the purpose of processing of the personal

data in this method along the definitions of Article

6 of the GDPR. It can be extended for use in com-

bination with a full-featured purpose management

system (see Section 6.3).

More annotations will be added in later revisions

of the toolset, but the approach should be obvious.

Obviously, such annotations are only put into the

source code for data items that are of personal or sen-

sitive nature themselves. Non-personal data, such as

counting variables or other implementation-specific

method parameters that are not of personal nature will

not be annotated at all, thereby will become omitted

for subsequent processing of the annotations.

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

392

Once these annotations are available and used

by the programmer in real-world environments, this

allows for multiple subsequent ways of processing,

ranging from visualizations (see next section) to data

exchange standardizations (see Section 6.1) to con-

sent and purpose management systems (see Sec-

tions 6.2 and 6.3).

5 DATA VISUALIZATIONS

Once the data fields, along with their status, interrela-

tion and properties is annotated, it becomes feasible to

automatically process such annotations—along with

the annotated source code itself—to support various

tasks around data protection and GDPR enforcement.

These are to be discussed in this section.

5.1 The Data and Purpose Spreadsheet

The most obvious way to make use of the annotations

of data items is to automatically compile lists of data

items of same status. No matter how big the source

code of an application gets, the task of searching for

all @data and @dataCreated annotations and aggre-

gating them into a simple list, sorted by status (per-

sonal/sensitive), is straight-forward, easy, and fast.

Thus, at all future points in time, everyone with ac-

cess to the source code can easily determine which

data items are processed by the particular software (or

parts thereof), which of those are of personal nature,

and which are of sensitive personal nature. Those

lists then can be used as a basis for all subsequent

tasks of GDPR enforcement, such as disclosure to-

wards the data subjects (cf. (European Parliament and

Council, 2016, Article 15)) or towards the data protec-

tion authorities (cf. (European Parliament and Coun-

cil, 2016, Article 57)), assessment of risks associated

with the data types processed, execution of a data pro-

tection impact assessment (cf. (European Parliament

and Council, 2016, Article 35)), and many more.

Similarly, apart from the data annota-

tions, it is possible to compile a list of all

@purpose annotations—along with the @data

and @dataCreated annotations used in the same

scope—to identify the purposes of data processing

relevant for a process. This list of puposes then can

be used as input for subsequent steps like compiling

a valid consent form to show and get signed off by

the data subjects, which must explicitly state all the

purposes relevant on why a system needs to process

a certain category of data items (cf. (European

Parliament and Council, 2016, Article 6.1(a))).

Another use of this map of purposes to data items

Figure 2: Visualization example for a single derived-from

relation.

may lie in the case that a data subject selectively

withdraws consent of processing of his/her data

for a specific purpose. In that case, the map can

easily be used to exactly pinpoint every single data

item associated with that purpose, along with the

exact locations of source code that handles such

data items. Thus, implementing such a selective,

separated-by-purpose processing system is made

way more easy as compared to the task of manually

searching for all potential data items assigned to a

certain purpose by hand.

However, the risk of this approach is that the lists

of data items and purposes may get lengthy and hard

to handle manually, especially if the same data is

listed multiple times under different names. To over-

come such issues of multiple entries of identical data

items or purposes, a mandatory preparational step is

to preprocess and unify the annotations, eliminating

different names for such identical data items, and

thereby reducing the size of the compiled lists. This

again is a straight-forwards process that can easily be

automated as well, and thus is not detailed here. Still,

the remaining list of data items is expected to rapidly

become lengthily in real-world processing systems.

5.2 The Data Subway Map

Visualization

In order to allow for better understanding of how the

data flows within the process, it is even more relevant

to not just list all data items as plain text, but to uti-

lize a suitable visualization for the data items, their

interrelation, and the resulting dependencies. Such a

visualization makes it more easy for a human asses-

sor to understand the way data is handled, processed,

stored, or forwarded within a system. A good dia-

gram makes every spreadsheet more comprehensible,

and the same holds true for the interdependencies of

data items in complex environments, especially when

focusing on their specific properties w.r.t. the GDPR.

Here, the approach used in the classification of data

comes in handy, as it directly separates input data

items from newly created data items. This allows

for precisely determining a relation among data items,

which we will dub the derived-from relation. A data

item X is derived from another data item Y iff Y is an

input data item to a source code method that annotates

data item X as being newly created by that method.

Towards Aligning GDPR Compliance with Software Development: A Research Agenda

393

Obviously, every data item can be derived from a sin-

gle to arbitrary many input data items, and can again

be used as input data to the creation/derivation of sub-

sequent data items. However, this relation allows for

a direction of data dependencies, which allows for

a suitable visualization of the creation flow of data

items performed by a processing system.

Figure 2 shows an example of a possible visualiza-

tion of such a derived-from data set. As can be seen,

the data item X is derived from Y, such that Y is the

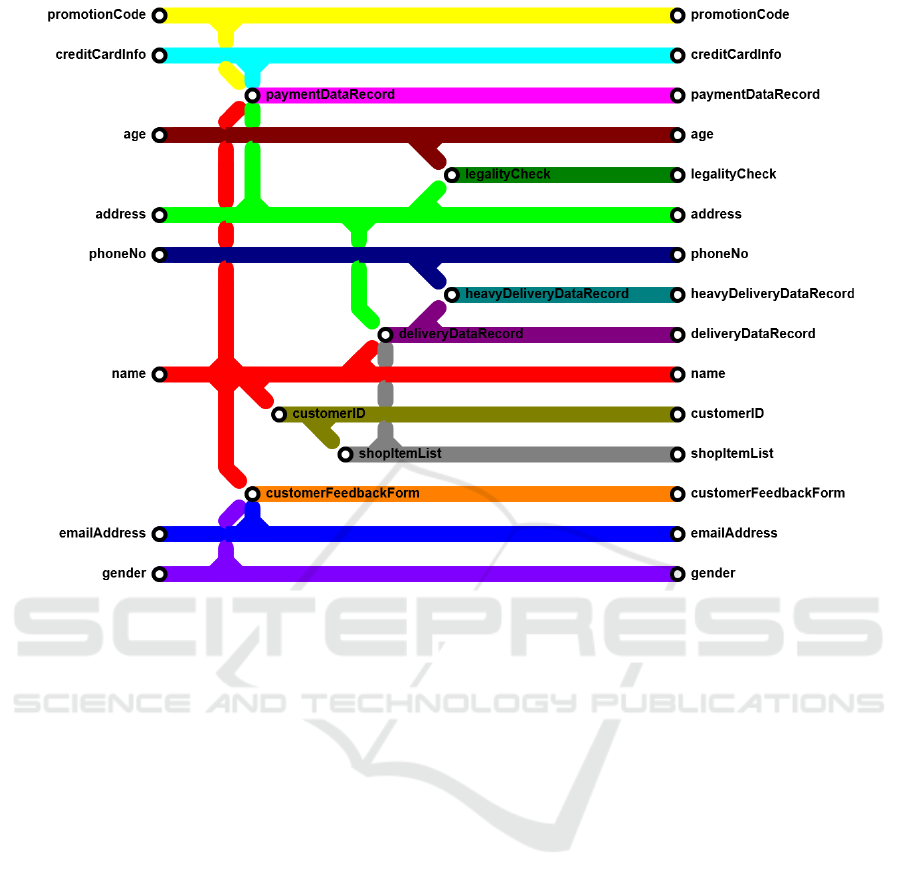

(only) input and both X and Y are outputs. Figure 3

illustrates this visualization approach in a more com-

plex scenario, with multiple inputs and derived data

items. The visualization used here has similar seman-

tics to a subway map, indicating points of intersection

(=derivations), but with a direction from left to right.

Thus, the left-most input data items of a system are

inputs gathered from the outside world (e.g. via user

input forms), and the right-most data items illustrate

the total set of data items used in the system.

The immediate purpose of such a visualization is

to easily get an impression of the flow of personal data

throughout a complex software system, and since it is

compiled automatically, it is no longer necessary to

understand the underlying source code at all. For a

quick assessment of personal data processed within a

system, this view thus is ideally suited to be used by

data protection assessors, e.g. in the context of per-

forming a data protection impact assessment (cf. (Eu-

ropean Parliament and Council, 2016, Article 35)).

Moreover, if a data subject decides to selectively

withdraw consent of processing for certain (input)

data items, this type of visualization immediately al-

lows to determine which other data items may be af-

fected by that decision as well. Vice versa, if an as-

sessor is interested to see what data is used as input to

create a certain data item, the visualization allows for

an easy determination when read from right to left.

Colored animations in the visualization editor could

even allow for more easy determination of such data

interdependencies in real-world usage scenarios, and

may e.g. be useful to highlight the flow of data of

sensitive personal nature.

6 DATA ANNOTATION

UTILIZATIONS

Beyond data visualization, which by itself is purely

intended to support a human mind in understanding

certain properties of a data processing system, there

are other major approaches for utilization of the data

annotations discussed in Section 4. Some of these are

outlined and briefly debated here, but obviously, there

is a large set of other approaches imaginable. Thus,

the set given here just reflects some very high-level

walk-through of some of the approaches that need to

be investigated in more detail in subsequent research

efforts.

6.1 Standardization of GDPR Metadata

Exchange Formats

A major issue of performing data flow assessments

e.g. in the context of a data protection impact assess-

ment according to Article 35 of the GDPR consists

in handing inter-organizational business processes. If

data is processed by external collaborators, such as

cloud providers or external data analytics services,

it becomes challenging to gather all information rel-

evant for determining the full data flows, purposes,

and processing conditions in a sound, complete, and

reasonable way. This process always requires direct

bilateral interaction between all collaborating orga-

nizations, something that can hardly be expected to

be achieved e.g. between a minor university’s IT

department and a major cloud provider. Hence, the

task of performing an overarching data protection im-

pact assessment for the full data processing of stu-

dent data, including the processes implemented and

privacy risks arising at the cloud provider, becomes

challenging if not impossible to manage.

A first step towards a solution of this challenge

consists in standardization: if organizations share

their particular GDPR-relevant information, such as

data flow visualizations and purpose lists, in a stan-

dardized, public, commonly understandable data for-

mat, that could help solving the issues of such

overarching DPIAs, risk assessments, transparency

requests, and consent withdrawal challenges im-

mensely. Hence, the development of a single, all-

inclusive, probably XML-based data format for ex-

change of GDPR-relevant metadata (data types, anno-

tations, purposes, etc.) is a promising venue to sup-

porting inter-organizational GDPR compliance im-

plementations. This is an ongoing work in our current

research efforts.

6.2 Consent Management

The challenges around the common practice of gath-

ering explicit consent for processing of personal data

from the concerned data subjects are numerous. If

a data processing system changes, does that imply

that all given consent forms for the old system be-

come outdated? Do they need to be updated? Do

the data subjects need to re-sign a new consent form?

If so, is it an incremental form, just highlighting the

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

394

Figure 3: Visualization example for a complex derived-from map of a larger system.

changes, or is it a complete consent form, covering

mostly things that the data subject has already con-

sented to in a previous consent-giving event?

In order to answer such questions, organizations

need to implement a sound consent management

framework, operated by the legal experts along with

the software developers, to address and react to all

types of (minor or major) changes in the design of the

data processing system. Especially in the age of ag-

ile software development, where new processing steps

and purposes can be added to a system on a weekly

basis, this task becomes even more challenging. Gr-

uschka and Jensen (Gruschka and Jensen, 2014) have

already started this debate, but the conjunction of that

issue with the data annotation system described in this

work looks promising for future research efforts.

6.3 Purpose Management

Similar to the consent management challenge, the

task of keeping track which data processing is nec-

essary for fulfilling which purpose, and to make sure

that no data is used outside of the purposes it is col-

lected and consented for, is a major issue when it

comes to GDPR compliance of organizations. Again,

given that the data annotation system already pin-

points the mapping of data items and purposes, it

tends to become very useful in supporting this task,

even to the point of complete automation. If a new

purpose annotation is set in the source code, the sys-

tem may—at deployment time—automatically update

the purpose database, validate the existing consent

to properly cover the combination of purpose and

data item, and alert the software developer in case

of a mismatch—or even decide to automatically up-

date the consent form and ask the data subject to re-

consent accordingly. Again, this task of purpose man-

agement indicates a lot of promising potential for fu-

ture research options.

6.4 Determination of Data Sensitivity

Factors

Another interesting avenue in the ”Data sensitivity”

challenge, is the determination of the factors effecting

sensitivity, further determining the degree of effect of

these factors on data type specific sensitivity. This

issue would also heavily influence continued compli-

ance to the GDPR in future. With the rise of Big Data

and Machine Learning techniques, derived data types

pose a significant threat to privacy. These secondary

and tertiary levels of data (In some cases far more)

must therefore have a schema in place to propagate

the sensitivity, post determination of the first level. As

Towards Aligning GDPR Compliance with Software Development: A Research Agenda

395

the complexity of the inheritance grows the determi-

nation of sensitivity would become a significant chal-

lenge to Privacy by Design approach as most often

data types could be automatically derived for a sub-

process which might not specifically be intended by

the original designers. Previous work by ULD (Con-

ference of the Independent Data Protection Authori-

ties of the Bund and the L

¨

ander, 2016) does begin to

give some insight on heuristics for factors, but there

are yet more factors that could be inferred depending

on the complexity of data; Data visualization support

should go a long way in combating this issue. Ap-

plying machine learning techniques to determine the

extent of effect and the factors themselves also pro-

vides an interesting research opportunity.

7 CONCLUSIONS

In the challenge of aligning the software develop-

ment process with the requirements introduced by the

GDPR, we have illustrated an initial data annotation

approach along with its utilization for data visual-

ization, standardization, and management. Based on

this observation, we outline several fields of appli-

cation, and call for an in-depth investigation of the

many research challenges arising from these. We

hope that future solutions in the envisioned research

areas will help organizations to achieve GDPR com-

pliance by using standardized, properly annotated, ag-

gregated, integrated data flow architectures that work

even in complex inter-organizational data processing

systems.

REFERENCES

Accorsi, R. and Stocker, T. (2012). On the exploitation of

process mining for security audits: the conformance

checking case. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual

ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, pages 1709–

1716. ACM.

Accorsi, R., Wonnemann, C., and Stocker, T. (2011). To-

wards forensic data flow analysis of business process

logs. In IT Security Incident Management and IT

Forensics (IMF), 2011 Sixth International Conference

on, pages 3–20. IEEE.

Conference of the Independent Data Protection Authorities

of the Bund and the L

¨

ander (2016). The standard data

protection model v1.0. Technical report.

De, S. J. and Le M

´

etayer, D. (2016). Privacy risk analysis.

Synthesis Lectures on Information Security, Privacy,

& Trust, 8(3):1–133.

European Parliament and Council (2016). Regulation (eu)

2016/679 – regulation on the protection of natural per-

sons with regard to the processing of personal data and

on the free movement of such data, and repealing di-

rective 95/46/ec (general data protection regulation).

Gruschka, N. and Jensen, M. (2014). Aligning user con-

sent management and service process modeling. In

GI-Jahrestagung, pages 527–538.

Kramer, D. (1999). Api documentation from source code

comments: a case study of javadoc. In Proceedings

of the 17th annual international conference on Com-

puter documentation, pages 147–153. ACM.

Object Management Group (2014). Business process model

and notation. Technical Report 2.0.2, Object Manage-

ment Group.

Object Management Group (2015). Unified modeling lan-

guage. Technical Report 2.5, Object Management

Group.

Oracle Inc. (2004). Javadoc 5.0, https://docs.oracle.com/

javase/1.5.0/docs/guide/javadoc/index.html.

Pedersen, C. B., Gøtzsche, H., Møller, J. Ø., and Mortensen,

P. B. (2006). The danish civil registration system. Dan

Med Bull, 53(4):441–449.

Pfitzmann, A. and Hansen, M. (2010). A terminol-

ogy for talking about privacy by data minimization:

Anonymity, unlinkability, undetectability, unobserv-

ability, pseudonymity, and identity management.

Schwartz, P. M. and Solove, D. J. (2011). The pii problem:

Privacy and a new concept of personally identifiable

information. NYUL rev., 86:1814.

Sharir, M. and Pnueli, A. (1978). Two approaches to inter-

procedural data flow analysis.

Valdman, J. (2001). Log file analysis. Department of Com-

puter Science and Engineering (FAV UWB)., Tech.

Rep. DCSE/TR-2001-04, page 51.

Van der Aalst, W. M. (2016). Process mining: data science

in action. Springer.

Zhou, B., Pei, J., and Luk, W. (2008). A brief survey on

anonymization techniques for privacy preserving pub-

lishing of social network data. ACM Sigkdd Explo-

rations Newsletter, 10(2):12–22.

ICISSP 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

396