Using Stigmergy as a Computational Memory in the Design of

Recurrent Neural Networks

Federico A. Galatolo, Mario G. C. A. Cimino and Gigliola Vaglini

Department of Information Engineering, University of Pisa, 56122 Pisa, Italy

Keywords: Artificial Neural Networks, Recurrent Neural Network, Stigmergy, Deep Learning, Supervised Learning.

Abstract: In this paper, a novel architecture of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) is designed and experimented. The

proposed RNN adopts a computational memory based on the concept of stigmergy. The basic principle of a

Stigmergic Memory (SM) is that the activity of deposit/removal of a quantity in the SM stimulates the next

activities of deposit/removal. Accordingly, subsequent SM activities tend to reinforce/weaken each other,

generating a coherent coordination between the SM activities and the input temporal stimulus. We show that,

in a problem of supervised classification, the SM encodes the temporal input in an emergent representational

model, by coordinating the deposit, removal and classification activities. This study lays down a basic

framework for the derivation of a SM-RNN. A formal ontology of SM is discussed, and the SM-RNN

architecture is detailed. To appreciate the computational power of an SM-RNN, comparative NNs have been

selected and trained to solve the MNIST handwritten digits recognition benchmark in its two variants: spatial

(sequences of bitmap rows) and temporal (sequences of pen strokes).

1 INTRODUCTION

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are today among

the most effective solutions for modeling time series,

speech, text, audio, video, etc. (Schmidhuber, 2015).

An RNN is a special type of NN using its internal

state (memory) to process sequences of inputs. This

internal memory makes the RNN able to remember

the relevant information about the previous samples,

in order to model their dynamics.

In contrast to Feed-Forward NN (FFNN), which

does not explicitly consider the notion of sequence, in

the RNN the input information cycles through a loop.

This structure allows the simultaneous processing of

both the current and the recent samples. In the RNN,

the deep learning algorithm tweaks its weights

through gradient descent and backpropagation

through time (BPTT, Mazumdar et al., 2008). In

essence, BPTT is backpropagation (BP) applied to an

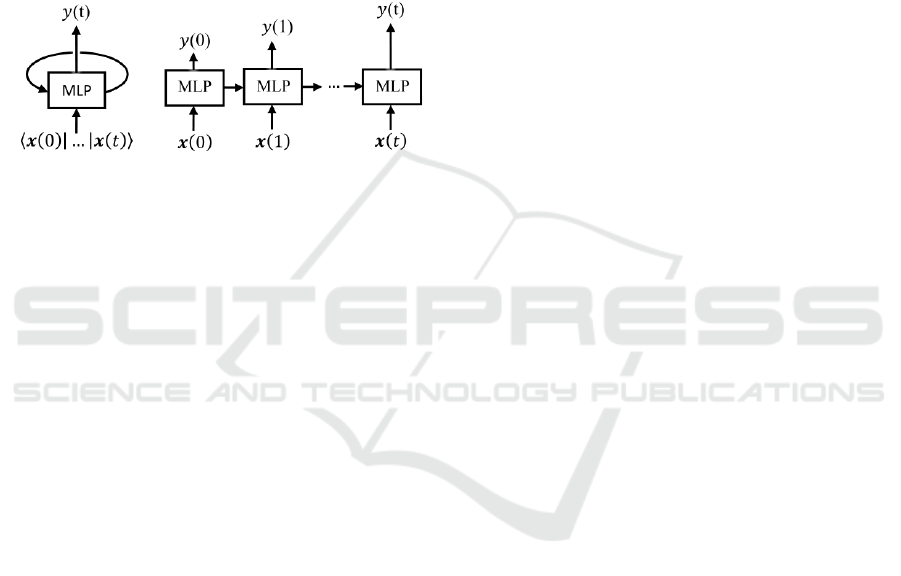

equivalent unfolded FFNN. Specifically, Figure 1a

shows a basic RNN, made by an MLP layer and a

cyclic connection from the output to the input neuron.

An RNN with finite response to finite length settles

to zero in finite time, and can be modelled as a

directed acyclic graph. This RNN can be unfolded

and transformed into an FFNN, i.e., an equivalent

static MLPs chain, with each MLP working at an

instant of time of the finite response, i.e., working

without memory (Figure 1b). Thus, within BBTT the

error is back-propagated from the last to the first time

step. The weights are updated by calculating the error

for each time step. Since the unfolded NN is static, it

can be trained by BP. However, in case of high

number of time steps, the unfolded NN is much

larger, and contains a large number of weights, which

makes BBTT computationally expensive.

A major issue with BP on large NN chains is

related to the gradient descent. In essence, BP goes

backwards through the NN to find the partial

derivatives of the error with respect to the weights, in

order to subtract the error from the weights. Such

derivatives are used by the gradient descent

algorithm, which iteratively minimizes a given

objective function. For better efficiency, the unfolded

NN can be transformed into a computational graph of

derivatives before training (Goodfellow et al., 2016).

A problem when training computational graph is to

manage the order of magnitude of gradients

throughout a large graph (Pascanu et al, 2013). The

exploding gradients problem occurs when error

gradients accumulate during an update. As a result,

very large gradients are produced and, in turn, large

updates to the network weights of long-term

830

Galatolo, F., Cimino, M. and Vaglini, G.

Using Stigmergy as a Computational Memory in the Design of Recurrent Neural Networks.

DOI: 10.5220/0007581508300836

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods (ICPRAM 2019), pages 830-836

ISBN: 978-989-758-351-3

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

components. This may cause network instability and

weights overflow. The problem can be easily solved

by clipping gradients when their norm exceeds a

given threshold (Goodfellow et al., 2016), by weight

regularization, i.e., applying a penalty to the networks

loss function for large weight values (Pascanu et al,

2013).

On the other side, the vanishing gradient problem

occurs when the values of a gradient are too small. As

a consequence, the model slows down or stops

learning. Thus, the range of contextual information

that standard RNNs can access is in practice quite

limited.

(a)

(b)

Figure 1: (a) An RNN (b) The equivalent NN unfolded in

time.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM, Graves et al.,

2009) is an RNN specifically designed to address the

exploding and vanishing gradient problems. An

LSTM hidden layer consists of recurrently connected

subnets, called memory blocks. Each block contains

a set of internal units, or cells, whose activation is

controlled by three multiplicative gates: the input

gate, the forget gate, and the output gate. An LSTM

network can remember arbitrary time intervals. The

cell decides whether to store (by the input gate), to

delete (by the forget gate), or to provide (output gate)

information, based on the importance assigned. The

assignment of importance happens through weights,

which are learned by the algorithm. Since the gates in

an LSTM are analog, in the form of sigmoid, the

network is differentiable, and trained by BP.

In recent years, LSTM networks have become the

state-of-the-art models for many machine learning

problems (Greff et al., 2017). This has attracted the

interest of researchers on the computational

components of LSTM variants.

This paper focuses on a novel concept of

computational memory in RNNs, based on stigmergy.

Stigmergy is defined as an emergent mechanism for

self-coordinating actions within complex systems, in

which the trace left by a unit’s action on some

medium stimulates the performance of a subsequent

unit’s action (Heylighen, 2016). To our knowledge,

this is the first study that proposes and lays down a

basic design for the derivation of Stigmergic Memory

RNN (SM-RNN). In the literature, stigmergy it is a

well-known mechanism for swarm intelligence and

multi-agent systems. Although its high potential,

demonstrated by the use of stigmergy in biological

systems at diverse scales, the use of stigmergy for

pattern recognition and data classification is still

poorly investigated (Heylighen, 2016). As an

example, in (Cimino et al.¸2015) a stigmergic

architecture has been proposed to perform adaptive

context-aware aggregation. In (Alfeo et al., 2017) a

multi-layer architectures of stigmergic receptive

fields for pattern recognition have been experimented

for human behavioral analysis. In (Galatolo et al.,

2018), the temporal dynamics of stigmergy is applied

to weights, bias and activation threshold of a classical

neural perceptron, to derive a non-recurrent

architecture called Stigmergic NN (S-NN). However,

due to the large NN produced by the unfolding

process, the S-NN scalability is limited by the

vanishing gradient problem. In contrast, the SM-RNN

proposed in this paper employs FF-NN as store and

forget cells operating on a Multi-mono-dimensional

SM, in order to reduce the network complexity.

To appreciate the computational power achieved

by SM-RNN, in this paper a conventional FF-NN, an

S-NN (Galatolo et al., 2018), an RNN and an LSTM-

NN have been trained to solve the MNIST digits

recognition benchmark (LeCun et al., 2018).

Specifically, two MNIST variants have been

considered: spatial, i.e., as sequences of bitmap rows,

and temporal, i.e., as sequences of pen strokes (De

Jong, E. D., 2018).

The remainder of the paper is organized as

follows. Section 2 discusses the architectural design

of SM-NNs. Experiments are covered in Section 3.

Finally, Section 4 summarizes conclusions and future

work.

2 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Let us consider, in neuroscience, the phenomenon of

selective forgetting that characterizes memory in the

brain: information pieces that are no longer reinforced

will gradually be lost with respect to recently

reinforced ones. This behavior can be modeled by

using stigmergy. Figure 2 shows the ontology of an

SM, made by four concepts: Stimulus, Deposit,

Removal, and Mark. In essence, the Stimulus is the

input of a stigmergic memory. The past dynamics of

the Stimulus are indirectly propagated and stored in

the Mark. This propagation is mediated by Deposit

and Removal: Stimulus affects Deposit and Removal

which, respectively, reinforces and weakens Mark.

Using Stigmergy as a Computational Memory in the Design of Recurrent Neural Networks

831

Mark can be reinforced/weakened up to a

saturation/finishing level. On the other side, Mark

itself affects Deposit and Removal. This behavior can

be characterized as recurrent.

Figure 3 shows an example of dynamics of a

mono-dimensional SM, i.e., a real-valued mark

variable, generically called 𝑚(𝑡). Specifically, the

mark starts from 𝑚

(

0

)

, and for 𝑡 = 0, … ,4 it

undergoes a weakening by ∆𝑚

−

(

0

)

, … , ∆𝑚

−

(

4

)

,

respectively, up to the finishing level 𝑚. For 𝑡 =

11, … ,13 the mark variable undergoes a

reinforcement by ∆𝑚

+

(

11

)

, … , ∆𝑚

+

(

13

)

,

respectively, up to the saturation level 𝑚.

Figure 2: Ontology of a stigmergic memory.

Figure 3: Example of dynamics of a mono-dimensional

stigmergic memory.

Let us consider a mono-dimensional Stimulus,

i.e., a real-valued variable generically called 𝑠(𝑡). For

each 𝑡, ∆𝑚

+

(

𝑡

)

and ∆𝑚

−

(

𝑡

)

are determined by

Deposit and Removal, respectively, on the basis of

𝑠(𝑡). Thus, 𝑚

(

𝑡

)

is a sort of aggregated memory of

the 𝑠(𝑡) dynamics. The relationship between 𝑚(𝑡)

and 𝑠(𝑡) is not prefixed. By using 𝑚(𝑡) to feed a

subsequent classification or regression unit, this

relationship can be trained via supervised learning.

According to this concept, Figure 4 shows the

structure of an SM-RNN based classification unit.

Here, the Deposit, Removal, and Classification MLPs

are realized by spatial FF-MLPs. The SM is based on

an array of M mono-dimensional mark variables,

where M is also equal to the number of outputs of the

Deposit and Removal MLPs, as well as to the number

of inputs of the Classification MLP.

Figure 4: Structure of an SM-RNN based classification unit.

Specifically, the Linear Layer at the input of

Deposit and Removal MLP is a single layer of linear

neurons, i.e., neurons with linear activation function.

It performs a linear projection of the SM data.

The three MLPs have the same structure,

represented in Figure 5: (i) an Input Linear Layer; (ii)

a PReLU (Parametric Rectified Linear Unit)

activation function, which solves the vanishing

gradient problem; (iii) an Output Linear Layer; (iv) a

ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation function, for

the Deposit and Removal MLPs, or a PReLU

activation function, for the Classification MLP,

respectively.

3 EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES

The architecture of an SM-NN has been developed

with the PyTorch framework (PyTorch, 2018) and

made publicly available on GitHub (GitHub, 2019).

The interested reader is referred to the GitHub

repository for further algorithmic details. The flow of

instructions has been modularized on different

abstraction levels, according to the best programming

ICPRAM 2019 - 8th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

832

practices, and it has been based on high-level

mathematical concepts. As a result, it is similar to

conventional pseudo-code, thanks to the support of

advanced machine-learning libraries, to encourage

open collaboration.

To appreciate the computational power of an SM-

RNN, different NNs have been trained to solve the

MNIST digits recognition benchmark (LeCun et al.,

2018): an SM-RNN, an FF-NN, an S-NN, an RNN

and an LSTM-NN.

Figure 5: Structure of a Deposit, Removal, or Classification

MLP.

The purpose is twofold: to measure the

computational power of SM-RNN with respect to FF-

NN, and to compare the performances of the other

existing temporal NN. For this purpose, the following

two variants of the MNIST benchmark have been

used.

In the Spatial MNIST dataset (LeCun et al., 2018),

the input image is made by 28×28 = 784 pixels, and

the output is made by 10 classes corresponding to

decimal digits. In the case of FF-NN, the handwritten

character is supplied in the form of full static bitmap.

For the other NNs, the handwritten character is

supplied row by row, in terms of 28 inputs, over 28

subsequent instants of time. In this case, once

provided the last chunk, the NN provides the

corresponding output class.

In the Temporal MNIST dataset (De Jong, E. D.,

2018), the handwritten character is supplied as a

sequence of pen strokes. In this case, at each instant

of time 𝑡, the next input is provided as a movement in

the horizontal and vertical directions (𝑑𝑥

(

𝑡

)

, 𝑑𝑦

(

𝑡

)

).

Once provided the last pen stroke, the NN provides

the corresponding output class. As an example,

Figure 6 shows the representation of a handwritten

digit in the Spatial MNIST (a) and Temporal MNIST

(b).

To adequately compare the different NNs, the

following methodology has been used. First, the FF-

NN and the SM-RNN have been dimensioned to

achieve their best classification performance.

Secondly, the S-NN, RNN and LSTM-NN have been

dimensioned to have a similar number of parameters

with respect to the SM-RNN.

Overall, the data set is made of 70,000 images. At

each run, the training set is generated by random

extraction of 60,000 images; the remaining 10,000

images makes the testing set.

(a)

(b)

Figure 6: representation of a handwritten digit in the Spatial

MNIST (a) and Temporal MNIST (b).

Table 1 shows the overall complexity of each NN.

The complexity values correspond to the total number

of parameters. Specifically, the SM is made by M =

15 mark variables. Thus, the Deposit and Removal

MLPs topology is made by 28 (temporal) + 15 (Linear

Layer) inputs, i.e. 43 inputs. The Linear Layer before

the Deposit and Removal MLPs contains 1515

weights + 15 biases = 240 parameters. The

Deposit/Removal MLPs contains the Input Linear

Layer (4320 weights + 20 biases = 880 parameters).

The PReLU contains 20 parameters. The Output

Linear Layer contains 2015 weights + 15 biases =

315 parameters. The Classification MLP contains the

Input Linear Layer (1510 weights + 10 biases = 160

parameters). The PReLU contains 10 parameters. The

Output Linear Layer contains 1010 weights + 10

biases = 110. Thus, the total number of parameter is

2402 + (880+20+315) 2 + (160+10+110) = 3,190.

For a detailed calculation of the complexity of the

other NNs, the interested reader is referred to

(Galatolo et al. 2018).

In addition, Table 1 shows the performance

evaluations, which are based on the 99% confidence

interval of the classification rate (i.e., the ratio of

correctly classified inputs to the total number of

inputs), calculated over 10 runs.

The Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) method

(Kingma et al., 2015) has been used to compute

adaptive learning rates for each parameter of the

gradient descent optimization algorithms, carried out

with batch method.

Using Stigmergy as a Computational Memory in the Design of Recurrent Neural Networks

833

Table 1: Performance and complexity of different NNs

solving the Spatial MNIST digits recognition benchmark.

Neural Network

Complexity

Classification rate

SM-RNN

3,190

.965 ± 0.056

FF-NN

328,810

.951 ± 0.0026

LSTM-RNN

3,360

.943 ± 0.011

S-NN

3,470

.927 ± 0.016

RNN

3,482

.766 ± 0.033

It is interesting to note in Table 1 that the SM-RNN

exhibits a classification accuracy similar to the best

NNs, i.e., LSTM-RNN and S-NN. The FF-NN,

although having a similar accuracy, employs a very

large number of parameters, about two order of

magnitude larger with respect to the others. Finally,

the RNN accuracy is sensibly lower. To assess the

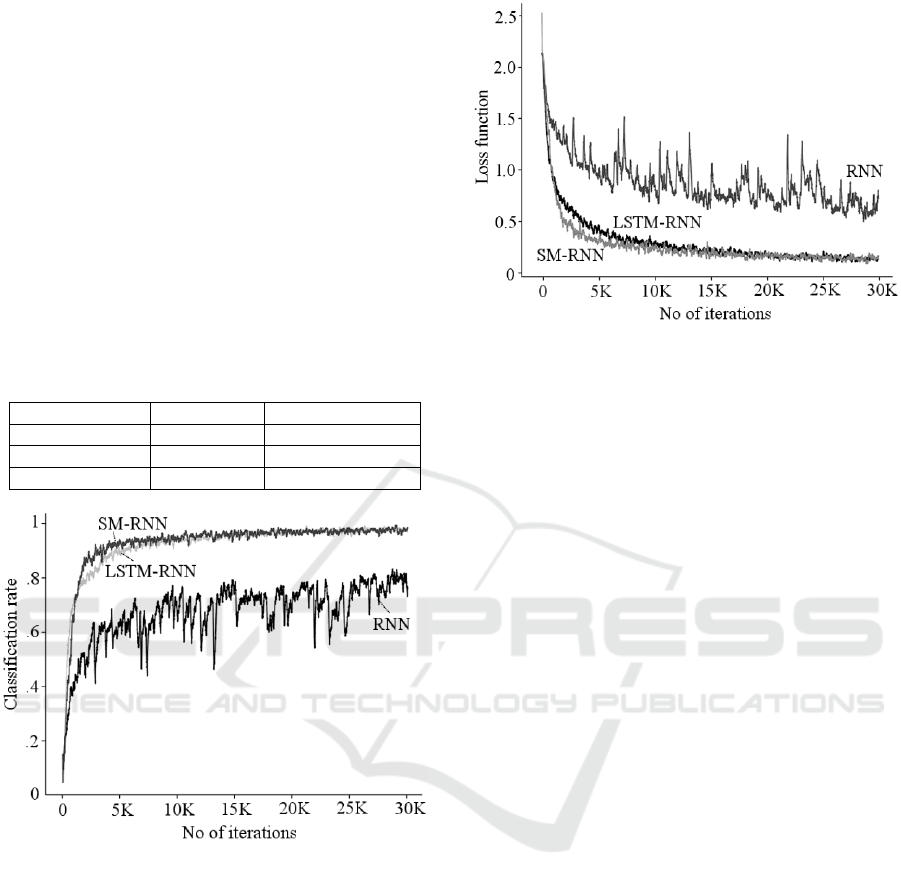

quality of the training process, Figure 7 and Figure 8

show a scenario of classification rate and the function,

on the training set, against the number of iterations,

respectively. The loss function is calculated as the

Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL) using the softmax

activation function at the output layer of the NN,

which is commonly used in multi-class learning

problems.

Figure 7: Scenario of classification rate on training set

against number of iterations, for the Spatial MNIST data

set.

With regard to the Temporal MNIST data set, three

kinds of temporal NNs have been used, i.e., SM-

RNN, LSTM-RNN, and RNN.

Table 2 shows the overall complexity of each NN.

The complexity values correspond to the total number

of parameters. Specifically, the SM is made by M =

30 mark variables. Thus, the Deposit and Removal

MLPs topology is made by 4 temporal inputs (i.e., the

horizontal and vertical directions, the stroke and digit

ends) + 30 (Linear Layer) inputs, i.e. 34 inputs. The

Linear Layer before the Deposit and Removal MLPs

contains 3030 weights + 30 biases = 930 parameters.

The Deposit/Removal MLPs contains the Input

Linear Layer (3420 weights + 20 biases = 700

parameters). The PReLU contains 20 parameters. The

Output Linear Layer contains 2030 weights + 30

biases = 630 parameters. The Classification MLP

contains the Input Linear Layer (3020 weights + 20

biases = 620 parameters). The PReLU contains 20

parameters. The Output Linear Layer contains 2010

weights + 10 biases = 210. The activation ReLU

contains 10 neurons. Thus, the total number of

parameters is 9302 + (700+20+630)2 + (620+20+

210+10) = 5,420.

Figure 8: Scenario of loss function on training set against

number of iterations, for the Spatial MNIST data set.

The Recurrent NN is made by the following layers:

an Input Linear Layer (3450 weights + 50 biases =

1,750 parameters), a PReLU (50 parameters), an

Output Linear Layer (5030 weights + 30 biases =

1,530 parameters), and an activation PReLU (30

parameters). Thus, the total number of parameters is

1,750 + 50 + 1,530 + 30 = 3,360. In the Recurrent

NN, each output neuron has a backward connection

to the input and to the Classification MLP which, in

turn, is made by the following layers: the Input Linear

Layer (3050 weights + 50 biases = 1,550

parameters), the PReLU (50 parameters), the Output

Linear Layer (5010 weights + 10 biases = 510), and

the activation PReLU (10 neurons). Thus, the total

number of parameters of the Recurrent and the

Classification NNs is 3,360+1,550+50+510+10 =

5,480.

The LSTM-RNN fed by 4 inputs. For each LSTM

layer, the number of parameters is calculated

according to the well-known formula 4o(i+o+1),

where o and i is the number of outputs and inputs,

respectively. The topology is made by a 4×20 LSTM

layer, a 20×20 LSTM layer, and a 20×10 Output

ICPRAM 2019 - 8th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

834

Linear layer. Thus, the overall number of parameters

is 420(4+20+1) + 420(20+20+1) + 2010 + 10 =

5,490.

In addition, Table 2 shows the performance

evaluations, based on the same criteria detailed for

Table 1. It is apparent from the table that the SM-

RNN and the LSTM-RNN are equivalent in terms of

classification rate. In contrast, the RNN is not able to

gain a sufficient stability and accuracy. To assess the

quality of the training process, Figure 9 and Figure 10

show a scenario of classification rate and loss

function, on the training set, against the number of

iterations, respectively. The loss function of Figure 10

is calculated as in Figure 8.

Table 2: Performance and complexity of different NNs

solving the Temporal MNIST data set.

Neural Network

Complexity

Classification rate

SM-RNN

5,420

.9467 ± 0.0076

LSTM-RNN

5,490

.9496 ± 0.0027

RNN

5,480

.7295 ± 0.1101

Figure 9: Scenario of classification rate on training set

against number of iterations, for the Temporal MNIST data

set.

Overall, the proposed SM-RNN shows a very good

convergence with respect to the other NNs. In

consideration of the relative scientific maturity of the

other comparative NNs, the experimental results with

the novel SM-RNN looks very promising, and

encourage further investigation activities for future

work.

Figure 10: Scenario of loss function on training set against

number of iterations, for the Temporal MNIST data set.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, the concept of computational stigmergy

is used as a basis for developing a Stigmergic

Memory for Recurrent Neural Networks. Some

important issues in the research field, related to the

gradient descent, are first discussed. The novel

architectural design of the SM-RNN is then detailed.

Finally, the effectiveness of the approach is shown via

experimental studies, carried out on the spatial and

temporal MNIST data benchmarks.

Early experimental results, carried out on different

NN architectures available in the literature for spatial

or temporal data, are promising. In particular, the SM-

RNN can be appreciated for its computational power

with respect to the static FF-NN, compared on the

spatial dataset. Moreover, the SM-RNN exhibits a

classification accuracy and a computational power

similar to the best temporal NN, i.e., LSTM-RNN, on

the spatial and temporal dataset.

In order to achieve more significant results, future

work will focus on further experimentation and

investigation, as well as on a further formalization of

the approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially carried out in the framework

of the SCIADRO project, co-funded by the Tuscany

Region (Italy) under the Regional Implementation

Programme for Underutilized Areas Fund (PAR FAS

2007-2013) and the Research Facilitation Fund

(FAR) of the Ministry of Education, University and

Research (MIUR).

Using Stigmergy as a Computational Memory in the Design of Recurrent Neural Networks

835

This research was supported in part by the PRA

2018_81 project entitled “Wearable sensor systems:

personalized analysis and data security in healthcare”

funded by the University of Pisa

REFERENCES

Alfeo, A. L., Cimino, M. G., Vaglini, G.: Measuring

Physical Activity of Older Adults vian SMartwatch and

Stigmergic Receptive Fields. In Proceedings of the 6th

International Con-ference on Pattern Recognition

Applications and Methods (ICPRAM), 2017, pp. 724-

730, Scitepress.

Cimino, M. G., Lazzeri, A., Vaglini, G.: Improving the

analysis of context-aware information via marker-based

stigmergy and differential evolution. In International

Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Soft

Computing (ICAISC), 2015, pp. 341-352, Springer

LNAI, Cham.

De Jong, E. D., the MNIST digits stroke sequence data,

https://github.com/edwin-de-jong/mnist-digits-stroke-

sequence-data, last accessed 2018/09/03.

Galatolo, F. A., Cimino, M. G. C. A., Vaglini, G. Using

stigmergy to incorporate the time into artificial neural

networks, in Proc. of the Sixth International Conference

on Mining Intelligence and Knowledge Exploration

(MIKE), 2018, pp. 248–258, Springer Nature

Switzerland AG, LNAI 11308.

GitHub platform, https://github.com/galatolofederico/

icpram2019, last accessed 2019/01/16.

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., Courville, A. and Bengio, Y.,

2016. Deep learning (Vol. 1). Cambridge: MIT press.

Graves, A., Liwicki, M., Fernández, S., Bertolami, R.,

Bunke, H. and Schmidhuber, J., 2009. A novel

connectionist system for unconstrained handwriting

recognition. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and

machine intelligence, 31(5), pp.855-868.

Greff, K., Srivastava, R.K., Koutník, J., Steunebrink, B.R.

and Schmidhuber, J., 2017. LSTM: A search space

odyssey. IEEE transactions on neural networks and

learning systems, 28(10), pp.2222-2232.

Heylighen, F: Stigmergy as a universal coordination

mechanism I: Definition and components. Cognitive

Systems Research, 38, 4-13, (2016).

Kingma, D. P., & Ba, J. L. (2015). Adam: a Method for

Stochastic Optimization. International Conference on

Learning Representations, 1–13.

LeCun, Y., Cortes, C., Burges, C.J.C.: The MNIST

database of handwritten digits, http://yann.lecun.com/

exdb/mnist/, last accessed 2018/09/03.

Mazumdar, J. and Harley, R.G., 2008. Recurrent Neural

Networks Trained with Backpropagation Through

Time Algorithm to Estimate Nonlinear Load Harmonic

Currents. IEEE Trans. Industrial Electronics, 55(9),

pp.3484-3491.

Pascanu, R., Mikolov, T. and Bengio, Y., 2013, February.

On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks.

In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp.

1310-1318).

PyTorch, Tensors and Dynamic neural networks in Python

with strong GPU acceleration, https://pytorch.org, last

accessed 2018/09/14

Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An

overview. Neural networks 61 (2015): 85-117.

ICPRAM 2019 - 8th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods

836