21st Century Skill Building with Web-based Games

William DeRusha

1

and Timothy Hickey

2

1

EdX, Cambridge MA, U.S.A.

2

Computer Science Department, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Keywords:

21st Century Skills, Game-based Education.

Abstract:

Financial knowledge has a tangible impact on an individual’s ability to make positive financial decisions in

their life. It has been estimated that the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile of the financial

literacy index is equivalent to approximately an 80,000 euro difference in net worth and has significant impact

on financial decisions made throughout one’s working life and into retirement. The need for quality financial

education is clear, but many studies show that personal finance classes offered today do not seem to have

significant impact on the financial literacy of the students who take them. One hypothesis of this paper is

that traditional instruction methods, which do not force students to exercise the financial tools they need to

be fluent with as adults, hinder their ability to improve their financial literacy. We also argue that analysis of

game interactions may be a more effective assessment mechanism than traditional academic tests. There is

a growing body of evidence that the immersive elements of particular styles of games can have a significant

impact on learning outcomes. This paper offers a potential starting point from which an immersive game,

which leverages real world financial decision-making as its main mechanic, can be born. We will discuss

the underlying design of such a game and how it lays the foundation for a game that could achieve financial

literacy outcomes. Such outcomes would empower students with the skills to make positive financial choices

in their lives and better achieve personal financial goals.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2005 at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, David

Foster Wallace gave a commencement speech which

began with a joke where one fish asks, “How’s the

water?” to which another fish replies “What is wa-

ter?”. This is an apt metaphor for the role that finances

and financial concepts play in our lives. Some people

are aware of them and their ubiquity, while others are

less conscious of finances and their impact. However,

regardless of awareness, finance is a topic that per-

meates modern day life. The vast majority will be

forced to manage liabilities such as credit cards, stu-

dent loans, and mortgages throughout their life. They

will make financial decisions in the midst of interest

rate data, depreciation schedules, and tax-favorable

savings vehicles. Their understanding of the financial

system will have a real, measurable impact on how

well they are able to navigate that world and the suc-

cess they are able to find on the other side of those

decisions.

One study by van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie on

financial literacy in the Netherlands found that the dif-

ference between the 75th and 25th percentile of peo-

ple on the financial literacy index is approximately

e80,000 in net worth, close to $100,000 USD at the

time of this writing (van Rooij et al., 2012). Other

analyses of the current literature by Mandell have

concluded that “results suggest that financial knowl-

edge is related to self-beneficial financial practices”.

Mandell also notes that “25 percent of undergraduate

college students have four or more credit cards and

about 10 percent carry outstanding balances between

$3,000 and $7,000.” The imperative of financial edu-

cation is not lost on educators. They see the differ-

ence education makes and understand that they must

arm students with the knowledge they need to handle

these commonplace scenarios.

The term “21st Century Skills” is used to describe

the wide-ranging body of skills, knowledge areas, and

core competencies required to succeed in 21st cen-

tury society and workplaces. There is still debate as

to exactly how to define and categorize the skills ex-

actly. However, most frameworks include financial

literacy among the required competencies, including

The Partnership for 21st Century Skills Framework.

196

DeRusha, W. and Hickey, T.

21st Century Skill Building with Web-based Games.

DOI: 10.5220/0007673201960203

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 196-203

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

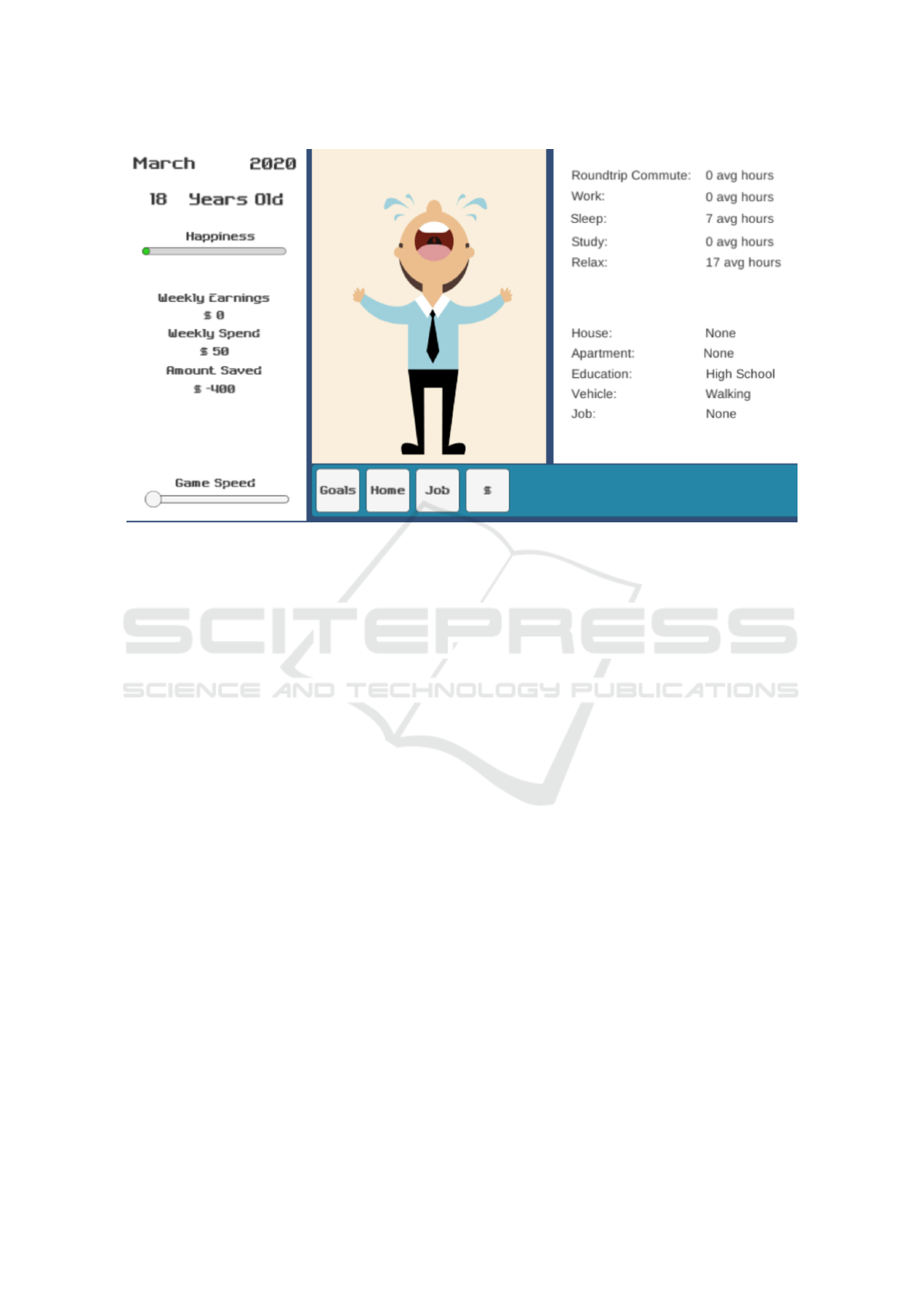

Figure 1: Simulation Screen. The left panel shows the current weekly status with a slider to adjust simulation speed. The

center panel is an visual representation of their current level of happineness. The right panel provides details about their

quality of life. The buttons on the bottom enable them to make life choices.

While there are multiple organizations pushing educa-

tors to adopt different 21st Century skill frameworks,

P21’s conceptualization of 21st Century skills is more

detailed and more widely adopted than any of the al-

ternatives (Dede, 2010). To further define this set of

skills, we can also look to The Jump$tart Coalition

for Personal Financial Literacy, which defines a set

of financial literacy standards in their publication of

“National Standards in K-12 Personal Finance Edu-

cation” (k12, 2015). It is from here that we can find

more granular definitions of financial skills to focus

on building and assessing.

With regard to assessment, one interesting find-

ing by Mandell (Mandell, 2009) on financial literacy

acquisition is the observation that personal finance

courses in college and high school don’t have a strong

impact on the student’s long term financial literacy

as assessed by traditional testing, but they do have a

positive impact on some areas of financial behavior.

This suggests that assessment using traditional multi-

ple choice and short essay questions may not be the

most effective way to measure the long term impact

of a financial literacy intervention.

It is the responsibility of educators to adapt and

create new content and pedagogies for ensuring the

success of students. Educators do not need to train

the next generation of students how to use the lat-

est technology, but as Marc Prensky says, they do

need to move away from the “old” pedagogy of teach-

ers “telling”, to the “new” pedagogy of kids teach-

ing themselves with a teacher’s guidance (Prensky,

2008). Game-based learning is one of the pedagogi-

cal approaches that fit this vision (Malone, 1980; Gee,

2003). It is the intent of this paper to propose that ed-

ucational games are an appropriate activity for K-12

classroom instruction and that they are potentially a

very effective medium for teaching financial concepts

and increasing desired financial literacy learning out-

comes.

In this paper we present an initial version of a

game to teach students to make effective financial de-

cisions in their lives. Fig. 1 shows the initial screen af-

ter the student starts the game when they are 18 years

old with no job and no housing.

2 RELATED WORK

There is a rich body of existing research on edu-

cational games ((Malone, 1980; Gee, 2003; Man-

dell, 2009; Kafai, 2006; Allery, 2004; Habgood and

Ainsworth, 2011) and the game this paper proposes

leverages many of these general educational game de-

sign concepts. Habgood discusses the value of intrin-

sically integrated games which fully engage the stu-

dent and in which the learning is intrinsically embed-

ded within the structure of the game itself. As the

player explores the gaming world they are also explor-

21st Century Skill Building with Web-based Games

197

ing the conceptual world of the learning domain, and

their interactions with the game correlate to deepen-

ing their understanding of these educational concepts

(Habgood and Ainsworth, 2011). This type of game-

play seems ripe for financial skills as it puts their ap-

plication at the forefront of the game strategy rather

than as an ancillary detail, thus encouraging more in-

teraction with the skills.

Understanding what makes a game effective is im-

portant in design. Gunter proposes a unique rubric

(RETAIN) for scoring educational games on their

ability to engage learners and affect learning out-

comes using the following six weighted factors: rel-

evance, embedding, transfer, adaptation, immersion,

and naturalization. (Gunter et al., 2008). This work

informed many of the choices made during the game

design phase and informs many of the proposed im-

provements to be made to the gameplay experience

in the future. In particular the initial game focuses

heavily on some of the highest weighted factors of

naturalization and adaptation, forcing players to syn-

thesize the multi-faceted financial impact of their de-

cisions on concepts that they are already familiar with

from everyday life. Sweetser and others have also

proposed models for evaluating player enjoyment in

games (Sweetser and Wyeth, 2005; Sweetser et al.,

2012) and this is an active and important area of re-

search in educational games.

Another important concept in game-based learn-

ing is the difference between instructionist and con-

structionist games. Kafai, in discussing technolog-

ical literacy (Kafai, 2006), argues that fluency in a

domain is more than just being able to recall defi-

nitions and solve standardized problems, it requires

the ability to use these skills and concepts to impact

the world in significant ways. For technological lit-

eracy this entails building computational artifacts, for

financial literacy it corresponds to making effective

life choices in a real or a game-based context. By

leveraging constructivist principles this game hopes

to empower learners to develop and transfer in-game

skills to the real world.

The importance of feedback cycles in gameplay

has been well-documented. Linehan notes that ef-

fective games provide players with a variety of dif-

ferent rewards whose effects on the player are easily

evaluated (Linehan et al., 2011) and computer games

are well-suited to deliver because they can continu-

ously monitor the player’s interactions with the game

and estimate which rewards are most effective, ed-

ucationally. While this particular type of dynamic

feedback cycle was deemed out of scope for the ini-

tial game, providing clear visual feedback to rein-

force positive behaviors certainly plays a role in guid-

ing learners through their decision-making as they ex-

plore the simulation game space. All of this existing

research was taken into account when determining the

exact pedagogical design goals of the pilot game.

3 PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN

GOALS

The overall goal of this project is to merge learn-

ings from existing research around educational game

effectiveness, traditional game design, and personal

finance education to create an education experience

that effectively teaches students the 21st century fi-

nance skills outlined by The Partnership for 21st Cen-

tury Skills Framework and further detailed in “Na-

tional Standards in K-12 Personal Finance Educa-

tion”.

In particular we focus on the following “Spending

and Savings” skills:

• Spending behaviors and habits affect personal sat-

isfaction.

• Use income to meet current obligations and future

goals.

• Every spending and saving decision has an oppor-

tunity cost.

The game is purposefully designed as an “intrinsically

integrated game” as described by Habgood which

means that it ”delivers learning material through the

parts of the game that are the most fun to play”. The

results of their studies provide strong evidence to sup-

port the benefits of such a game, with the children ex-

posed to the intrinsic game making the most learn-

ing gains of any group in the study (Habgood and

Ainsworth, 2011).

Another design goal of this project is to engage

students in a way that they identify as the main char-

acter. This is achieved in the few ways. First, by

forcing the learners to choose their own financial

goals, they can take ownership of helping the char-

acter achieve those goals. We also build some owner-

ship specifically by avoiding common ownership pit-

falls as described by Shirts including “assigning at-

titudes and values along with the role”, “determin-

ing consequences with a model which the participant

feels is inappropriate or inaccurate”, or “making the

choices obvious so the consequences have little mean-

ing.” (Shirts, 2013). Fig. 1 shows the initial screen

shot from the simulation phase when the player has no

job and no housing. It accurately captures the mood

of many students as they transition from high school

to college or a working life.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

198

Figure 2: Welcome screen and First Life Goal Screen. The player is given a general overview of the goal of the game and

must start by choosing life goals which cannot be changed during the game play.

As stated earlier in this paper, traditional college

courses on personal finance do not seem to have a

significant impact on financial literacy, but they seem

to have some impact on financial behavior (Mandell,

2009). We propose that the reason finance courses do

not impact literacy in the same way that they impact

behavior is the lack of application. By creating an

intrinsic game where students must set goals and em-

ploy financial skills to achieve them they will have

more grounded learnings that carry with them into

real world scenarios. We also hypothesize that such

a game can be used for assessment as a better proxy

for real world outcomes than existing financial liter-

acy assessment, which is typically exam-based.

By leveraging these design insights in the pilot

game we hope to see students applying many of the

stated 21st Century finance skills in conjunction with

each other. It was important to ensure that the game

was not simply one in which the student grinds out the

maximum amount of money to win, but instead makes

choices and uses financial tools to achieve their per-

sonal experiential goals while maximizing their aver-

age and final happiness.

4 INITIAL GAME DESIGN

Each game can be completed in a few minutes and

we assume that each user will play the game multi-

ple times. The game

1

is divided into three phases as

follows:

• pregame phase is where the player selects their

personalized life goals for the game,

1

The initial version of this game can be played at

https://21centurygames.github.io/

• simulation phase is where they make decisions

that effect the quality of their life,

• endgame phase is where the salient results of their

simulated life are summarized.

4.1 Pregame

In the pregame screens shown in Fig. 2, the player

is given a light narrative of what’s to come, priming

them for the decisions they will need to make on the

next screen. Once they have started the game they

are immediately asked to set some life goals for their

avatar. The current version has only two types of

goals:

• living style (urban, suburban, rural)

• education (BA, MA, PhD)

There is purposefully little direction here as to the im-

portance of this selection and its impact on the game

to encourage players to select goals that map to their

own goals rather than choosing goals to influence any

in-game objectives. One of the goals of the game is to

help player explore the consequences of real-life de-

cisions. In particular, getting a higher level of educa-

tion increases the opportunities for employment and

the potential for a higher annual salary. Likewise, liv-

ing in the country results in a fewer job opportunities

or longer (and possibly prohibitive) commute times.

The commute times can be ameliorated by purchasing

a car, but this requires savings. These consequences

are not explained in the pregame screens; players will

discover these consequences when they look for a job

and see how their income compares to their expenses.

21st Century Skill Building with Web-based Games

199

4.2 Simulation and Player Agency

After selecting their goals the simulation begins and

the player is shown the Simulation Screen in Fig. 1.

The simulation screen can be divided into 4 sections.

A fluctuating data section on the left, an avatar sec-

tion in the middle, a decision result section on the

right, and an action section along the bottom. In

the fluctuating data section the player can see the

current date and the avatar’s current age, as well as

what things happens as time passes. The amount

they earn and spend impacts how much savings they

have. Their overall happiness monitor ebbs and flows

as they make decisions in the game and attempt to

achieve their financial goals. In the avatar section a

simple avatar reflects the current mood of the player

as shown in Fig. 3. The image changes in concert with

the happiness bar to provide an emotional indicator to

the player as to how they feel about their situation.

Figure 3: Three visual levels of avatar satisfaction. The

sad figure indicates life threatening situations such as home-

lessness or working/commuting with no time to sleep. The

happy figure indicates that the avatar’s lifegoals have been

achieved.

In the decision result section the player can see

the current state of their choices, some features are

directly in their control and some indirectly. For ex-

ample, they can choose to own a vehicle and live in

a certain place (direct choices). This section will also

show things like time spent commuting (an indirect

outcome of their transportation choice, home location

choice, and work location choice).

Finally, the action section consists of a series of

buttons that allow the player to make their in-game

decisions about where to live, what jobs they want to

have, and what items they want to purchase. They

can also control the speed of the game, slowing down

gameplay to make a handful of decisions and then

speeding it up to see how those decisions impact their

avatar over time.

The simulation ends when the avatar passes away.

The precise time of death for the player’s avatar is

based on the latest statistical data about average lifes-

pans in the United States(nat, 2006), wealth is not fac-

tored in to the lifespan calculation, though it might be

more accurate to include poverty as a negative impact

factor on lifespan.

4.3 EndGame

When the avatar’s simulated life is over, the game

displays a summary screen which the player can use

to judge whether they have lived a successful life.

A sample screen is shown in Fig. 4. The summary

screen currently shows average and final happiness as

well as the number of goals met, but does not indi-

cate how much money, if any, they had saved. After

playing the game a few times, it becomes clear that

the goal is to meet your goals and attain the highest

average and final happiness.

Figure 4: Summary Screen showing results of the simulated

life.

5 GAME ARCHITECTURE

We decided to use an industry standard game engine,

Unity3D, to encourage future improvements to the

game’s visual aesthetic. By using a fully featured

game engine we have the flexibility to take the un-

derlying simulation code and map it to any number of

visual representations. For this initial pilot the visu-

als are simple, but the path to future UI enhancements

is straightforward using the Unity framework. Each

object in the simulation has a corresponding display

object that is 2D for this pilot game, but to create and

integrate 3D objects would not alter the backing sim-

ulation in any way.

Under the hood the simulation leverages a consis-

tent interface pattern, which allows future developers

to register new types of game objects and integrate

them easily into the simulation. The most prevalent

example of this is that each game object implements

its own “onTick” function that is called each time the

simulation moves forward in time. This allows each

game object to manage its own simulated state. What

that means for development is that each object’s sim-

ulation can be made as complex or simple as desired

without altering the rest of the system.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

200

The final major architecture choice that enhances

our ability to improve upon the game design is the

use of Unity3’s scriptable objects. By designing ob-

ject templates it is trivial to test many variations of the

game using new values. It is possible to have people

not familiar with the underlying code generate these

objects and put them into the game. This is an effec-

tive way to test difficulty levels when tuning the game

for general use or for a particular player demographic.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The existing research shows that there are key strate-

gies that can be employed in game design to enhance

learning outcomes and keep players engaged with the

game content. There are also many standards bodies

designing skill-based outcomes to be used assess stu-

dents abilities to learn new skills for which there is no

standard curriculum. However, since current assess-

ments of financial literacy are not strongly impacted

by traditional teaching methods it is reasonable to ap-

ply findings in effective educational game design re-

search to 21st century financial literacy skills in an

attempt to give students alternative ways to exercise

financial skills and potentially to evaluate financial lit-

eracy. The pilot game designed is one such attempt

that can be iterated upon with user feedback to ap-

proach achieving those outcomes.

7 FUTURE WORK

In the future our plan is to run a pilot study to assess

the effectiveness of this approach in producing posi-

tive learning outcomes, and to expand the scope of the

game play to include additional 21st Century Skills

7.1 Gameplay Tuning

A critical phase of game development is the playtest

phase. This helps to tune many of the nuances of

game mechanics. Allowing the designers to adjust

and tweak small things like the cost of items, scor-

ing mechanisms, and game tempo. It can also result

in larger changes like redesigning the user interface.

Since the game has yet to enter this phase of devel-

opment it should be expected that there are many im-

provements to be made which are not yet known and

will be discovered through playtesting and user feed-

back.

It is important to consider the balance of tradi-

tional playtesting and expected learning outcomes.

That is one area where having the financial skills as an

integrated game mechanism helps ease some of this

tension. One does not need to sacrifice educational

content to increase playability. Also, in terms of bal-

anced gameplay, a financial game is unique in that it

can draw much of its data from the existing markets

that are naturally balanced. Using up-to-date salary,

housing, and commercial goods pricing data ensures

the proper balance but also increases the realism of

the game and the likelihood that skills are transferable

outside of the game.

The biggest area where the game, in its current

state, feels to be lacking is the level of immersion.

This is probably the most challenging part of design-

ing a game around an abstract concept such as finance.

With other simulation games like SimCity, the visual

construction integrated into the gameplay experience

effectively immerses players in the game. With ab-

stract simulations there is no natural immersion so it

is up to the game designer to determine how to incor-

porate the gameplay elements in an immersive way.

The game could, in theory, be played inside of a ro-

bust excel spreadsheet. It is paramount that playtest-

ing phase garners feedback in how to make the game

more immersive to keep players engaged long enough

for learning to take place.

7.2 The Challenge of Assessment

A valid assessment of skills is paramount to under-

standing the educational value in playing this game. It

is not clear from the literature exactly what financial

literacy assessments were used in evaluating financial

literacy claims discussed by Mandell, but if financial

courses are not significantly impacting financial lit-

eracy scores but are, however, positively impacting

some financial habits of individuals then it is not an

unreasonable conclusion that we may be evaluating

based on the wrong criteria. Using a more traditional

pre-test and post-test method may still be a reason-

able approach but more investigation would be neces-

sary to ensure that we do not fall into the same trap of

evaluating literacy skills as having not improved de-

spite observing the positive application of those skills

(which is the true intent of the instruction).

Since the game itself requires players to exercise

financial skills and understand financial concepts it is

possible that the results a player achieves in the game

can be a reasonable proxy for skill and knowledge ac-

quisition. Let’s take a look at the three granular finan-

cial concepts targeted by the game and how gameplay

could be used to evaluate them.

The players ability to increase the happiness of

their avatar requires an understanding of how “spend-

ing behaviors and habits affect personal satisfaction”.

21st Century Skill Building with Web-based Games

201

The richer and more complex the spending and life-

action options that are made available to the player,

the more connections to this skill they will be forced

to make. Assessing the players’ final happiness scores

as well as how quickly they are able to leverage

spending and habits to get such scores will indicate

a mastery and understanding of that skill.

Similarly, achieving goals is a main mechanism of

the game and the primary way to build in-game hap-

piness. Thus, measuring how quickly players are able

to achieve certain in-game goals is a very good proxy

for their development of the skill of “using income to

meet current obligations and future goals”.

The last piece of understanding, where “every

spending and saving decision has an opportunity cost”

is not as directly integrated into the game mechanics

as the first two. The game does require certain mile-

stones to be met before some actions are available,

for example needing a bachelors degree before get-

ting access to certain jobs. Players are forced to make

the trade-offs between spending money on education

to access those jobs and saving money for items like

vehicles to help them commute faster to jobs. As a

matter of course players engage with these decisions

and players who do well in the game are those who are

able to manage opportunity costs appropriately. One

way in which using gameplay results as an assessment

of this skill could be correlated more strongly would

be giving the players differently balanced games and

seeing if they still make the same trade-offs. Players

who do well in all versions of the game could be said

to understand this financial concept.

While the assessment of skills and understanding

is one thing, an open question remains as to the trans-

ferability of in-game skills to real life. Using more

longitudinal observations of players real life financial

activities would allow for even stronger evidence that

the game itself and the virtual application of real fi-

nancial tools is an effective method for teaching and

evaluating the understanding of those tools.

7.3 Feature Enhancement

There are many future improvements that would be

interesting to explore in this field. The decision to

pursue any of these should be informed by the initial

results of the pilot study. However, some possible ar-

eas of exploration that likely make sense are:

• The usage of closed loop feedback systems to

keep learners in the zone of proximal develop-

ment.

• Using socio-economic status starting situations to

build empathy for others as well as to be able to

better reflect the student in the avatar.

• Using existing data and statistics to more accu-

rately simulate market conditions and provide a

more realistic experience for the players.

• Include more immersive game elements, both au-

ral and visual, to make the student more engaged

with the content.

• Leaning on the RETAIN model, including more

immersive game elements, both aural and visual,

to make the student more engaged with the con-

tent.

• Focusing on improving the transferability of in-

game skills (another improvement born of the RE-

TAIN model).

REFERENCES

(2006). Life table for the total population: United states,

2003. National Vital Statistics Reports, 54(14).

(2015). National standards in k-12 personal finance educa-

tion.

Allery, L. A. (2004). Educational games and structured ex-

periences. Medical Teacher, 26(6):504–505.

Dede, C. (2010). Comparing frameworks for 21st century

skills. 21st century skills: Rethinking how students

learn, 20:51–76.

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about

learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment

(CIE), 1(1):20–20.

Gunter, G. A., Kenny, R. F., and Vick, E. H. (2008). Taking

educational games seriously: using the retain model

to design endogenous fantasy into standalone educa-

tional games. Educational technology research and

Development, 56(5-6):511–537.

Habgood, M. J. and Ainsworth, S. E. (2011). Motivating

children to learn effectively: Exploring the value of

intrinsic integration in educational games. The Jour-

nal of the Learning Sciences, 20(2):169–206.

Kafai, Y. B. (2006). Playing and making games for learn-

ing: Instructionist and constructionist perspectives for

game studies. Games and culture, 1(1):36–40.

Linehan, C., Kirman, B., Lawson, S., and Chan, G. (2011).

Practical, appropriate, empirically-validated guide-

lines for designing educational games. In Proceedings

of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in com-

puting systems, pages 1979–1988. ACM.

Malone, T. W. (1980). What makes things fun to learn?

heuristics for designing instructional computer games.

In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SIGSMALL sympo-

sium and the first SIGPC symposium on Small sys-

tems, pages 162–169. ACM.

Mandell, L. (2009). The impact of financial education in

high school and college on financial literacy and sub-

sequent financial decision making. In American Eco-

nomic Association Meetings, San Francisco, CA, vol-

ume 51.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

202

Prensky, M. (2008). The role of technology. Educational

Technology, 48(6).

Shirts, R. G. (2013). Ten ’mistakes’ commonly made by

persons designing educational simulations and games.

Sweetser, P., Johnson, D. M., and Wyeth, P. (2012). Re-

visiting the gameflow model with detailed heuristics.

Journal: Creative Technologies, 2012(3).

Sweetser, P. and Wyeth, P. (2005). Gameflow: a model for

evaluating player enjoyment in games. Computers in

Entertainment (CIE), 3(3):3–3.

van Rooij, M. C., Lusardi, A., and Alessie, R. J. (2012).

Financial literacy, retirement planning and household

wealth*. The Economic Journal, 122(560):449–478.

21st Century Skill Building with Web-based Games

203