A Service Definition for Data Portability

Dominik Huth, Laura Stojko and Florian Matthes

Chair of Software Engineering for Business Information Systems, Technical University of Munich, Boltzmannstr. 3,

Garching, Germany

Keywords:

GDPR, Privacy Engineering, Soft Privacy, Data Portability, Service Definition, Information Model.

Abstract:

Data portability is one of the new provisions that have been introduced with the General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR) in May 2018. Given certain limitations, the data subject can request a digital copy of

her own personal data. Practical guidelines describe how to handle such data portability requests, but do not

support in identifying which data has to be handed out. We apply a rigorous method to extract the necessary

information properties to fulfill data portability requests. We then use these properties to define an abstract

service for data portability. This service is evaluated in seven expert interviews.

1 INTRODUCTION

After a two-year period of discussion and preparation,

the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Eu-

ropean Union, 2016) is finally being enforced since

May 2018. It introduced updated definitions for per-

sonal data and the territorial scope, enhanced data

subject rights, the adoption of privacy by design and

default, and extended responsibilities for data proces-

sors (Tikkinen-Piri et al., 2017). Even though the first

wave of attention for the GDPR has settled, many

companies still lack the resources (or, in some cases,

the willingness) to become fully compliant. In fact,

the first fines based on the new regulation are now

under way (Allen, 2018) and further incidents are ex-

pected. Research on methods and tools to deal with

GDPR requirements is all but finished.

A new right established with the GDPR is data

portability (Article 20). The data subject now has

the right to ”receive the personal data concerning

him or her [...] in a structured, commonly used and

machine-readable format” and the right to ”trans-

mit those data to another controller” or ”have the

personal data transmitted directly” (European Union,

2016).

Researchers identify a series of challenges for the

implementation of data portability. As a right af-

fecting both privacy legislation and competition law,

companies are hesitant in supporting the migration of

their customers to a competitor (Vanberg and

¨

Unver,

2017) and portability standards are missing (Bistolfi

et al., 2016). However, data portability could also

help in creating a new kind of data economy where

data subjects leverage their data in multiple organiza-

tions (De Hert et al., 2017).

The research goal of this paper is to further ad-

vance the information extraction according to Art. 20

GDPR. We will accomplish this goal with the follow-

ing research questions:

• RQ1: What are the information requirements for

the fulfillment of Art. 20 GDPR?

• RQ2: How can a data gathering service be de-

fined?

• RQ3: How useful or applicable is the approach

proposed in this paper?

2 RESEARCH OUTLINE

In this section, we present our research process for de-

veloping and assessing the service definition for data

portability.

First, we shortly survey prominent work of the Pri-

vacy Engineering field and position our work within

the established frameworks for matching require-

ments and technical approaches in section 3.

To answer RQ1, we apply an established method

called semantic parametrization (Breaux et al., 2006)

to conduct a thorough analysis of the legal provisions

within Art. 20 GDPR. From the resulting semantic

model of the regulation, we conduct a further analy-

sis to extract the necessary properties for identifying

Huth, D., Stojko, L. and Matthes, F.

A Service Definition for Data Portability.

DOI: 10.5220/0007677101690176

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), pages 169-176

ISBN: 978-989-758-372-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

169

data that is subject to data portability. This process is

described in section 4.

Data portability is then defined as an abstract,

platform-independent service fulfilling the require-

ments identified with RQ1. An information model

describes the abstract representation of data structures

with personal data. We specify a process for respond-

ing to data portability requests and demonstrate the

process using a well-known data model in section 4,

answering RQ2.

RQ3 is addressed through seven qualitative, semi-

structured interviews with IT experts in various po-

sitions of multiple organizations. The interviews are

described in detail in section 7.

We discuss our findings and additional outcomes

regarding the experts’ opinion on the GDPR and state

possible future research directions in section 8.

3 POSITIONING IN PRIVACY

ENGINEERING CONTEXT

The field of Privacy Engineering, as defined by

(G

¨

urses and Del Alamo, 2016), focuses on systemat-

ically capturing and addressing privacy issues in sys-

tem engineering processes. This is a particular chal-

lenge, since the word privacy generally serves a an

umbrella term for a set of related problems (Solove,

2007), and thus does not contribute to a clear picture

of the necessary actions. In an engineering context,

eliciting privacy requirements equates to identifying

properties that need to be fulfilled or prevented when

designing a system.

For privacy requirement elicitation, (Notario et al.,

2015) identify two complimentary approaches: the

top-down or goal-based approach, where desirable

privacy properties serve as the starting point; and

the bottom-up or risk-based approach, which analy-

ses a system design for exposure to non-desirable out-

comes or anti-goals.

An example for a top-down approach is the

PriS method (Kalloniatis et al., 2008), which de-

fines the desirable properties Authentication, Autho-

rization, Identification, Data Protection, Anonymity,

Pseudonymity, Unlinkability and Unobservability,

which are addressed by so-called privacy process pat-

terns. This method does not specifically address data

subject rights, such as data portability requests. We

will define a process pattern for such requests later in

this paper, which also refers to the process pattern of

authentication.

On the opposite side, the LINDDUN method

(Deng et al., 2011) is an example for a risk based

approach. It was developed as a privacy analogy to

Microsoft’s STRIDE method for identifying security

threats (Microsoft, 2009) and focuses on anti-goals

in the privacy domain.

1

The authors categorize pri-

vacy goals into hard privacy and soft privacy and as-

sign the corresponding anti-goals to these two cate-

gories. Linkability, Identifiability, Non-repudiation,

Detectability and Information Disclosure are cate-

gorized as hard privacy anti-goals, whereas Content

Unawareness and Policy and consent Noncompliance

belong to the soft privacy category. Similarly, (Spiek-

ermann and Cranor, 2009) distinguish between pri-

vacy by policy and privacy by architecture. After elic-

iting the privacy requirements, countermeasures are

matched to the identified risks.

In this work, we focus on the soft privacy goal of

content awareness. In order to make informed deci-

sions about sharing (or continuing to share) personal

information with a controller, a data subject has to

be aware of which personal information is being pro-

cessed. In some cases, such as credit ratings or health

information, it is important to ensure accuracy of the

data and, subsequently, prevent erroneous decisions.

The right of access and the right to rectification are

crucial for this function.

With the enhancement of data subject rights and

the introduction of data portability in the GDPR,

there is also a need to develop methods to respond to

these privacy requirements systematically. Since we

do not see corresponding countermeasures or mitiga-

tion strategies within the established frameworks, we

would like to advance the view that the implementa-

tion of data subject rights should be included in pri-

vacy engineering frameworks. This work constitutes

the first step in this direction.

Nonetheless, there is already some practical ad-

vice available for how to handle data portability re-

quests. The Article 29 Working Party was established

as an independent advisory body to the European

Union and is formed by European data protection of-

ficers. Their “Guidelines on the right to data porta-

bility” (Article 29 Data Protection Working Party,

2017) discuss under which conditions data portabil-

ity applies, what data must be included and how and

in which formats it should be provided. Although

this document addresses many important questions,

to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no ser-

vice definition available on how relevant data for data

portability can be identified.

1

The acronym LINDDUN, just like the acronym

STRIDE, is composed from the initial characters of the anti-

goals.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

170

4 REQUIREMENT ANALYSIS

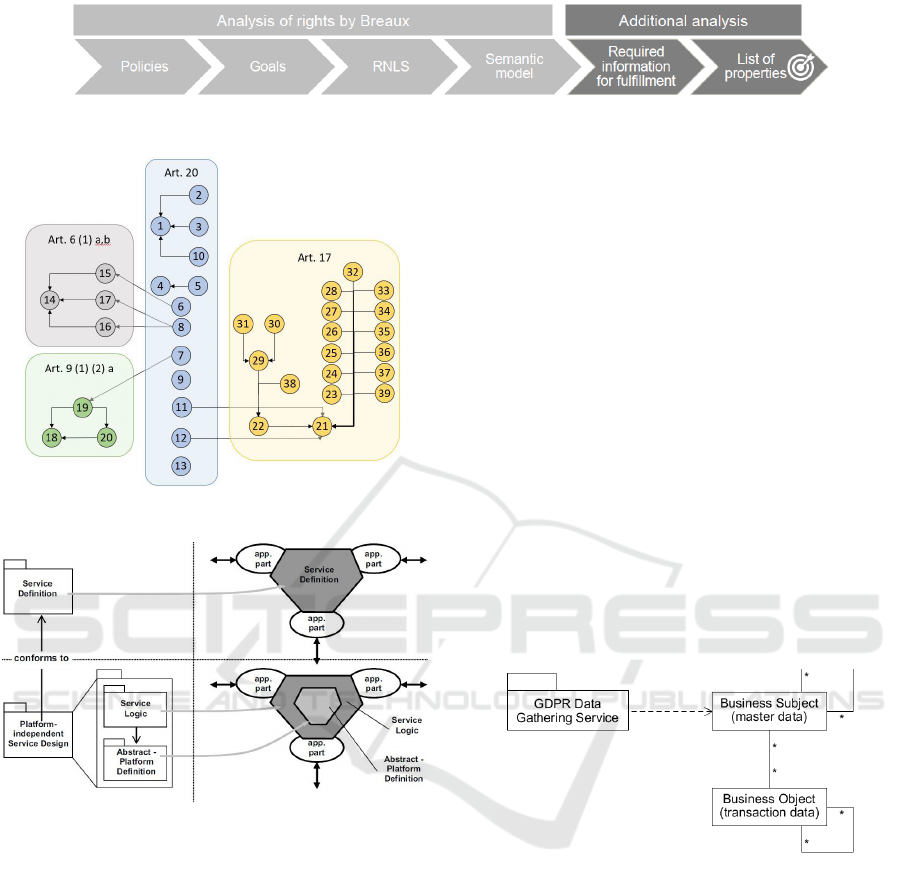

(Breaux et al., 2006) identify a mismatch between re-

quirements specified in legal provisions and actual

system requirements. To bridge this gap, the au-

thors establish a process called semantic parametriza-

tion. It comprises the steps policy selection, goal

mining, identification of restricted natural language

statements (RNLS) and semantic modeling, which we

will describe for Art. 20 in the following paragraphs.

Additionally, we extracted the necessary information

items from the resulting semantic model. These in-

formation items represent the information that needs

to be accounted for when gathering data for a request

pursuing Art. 20 GDPR. The process is visualized in

Figure 1.

The process starts with the policy selection, which

is Art. 20 GDPR in our case. In the goal mining step,

the natural language statements within Art. 20 are

reformulated into single goals, e.g.

“The data subject shall have the right to re-

ceive the personal data concerning him or her,

which he or she has provided to a controller,

in a structured, commonly used and machine-

readable format”

is restated into goals which are exemplified in Ta-

ble 1. This yields a list of 16 unique goals for Article

20. Since some of the goals refer to other articles (i.e.

Art. 6, Art. 9 and Art. 17), semantic parametriza-

tion was applied to these articles as well, but is not

displayed here.

Table 1: Example for goals within Art. 20 GDPR.

Actor Action Subject Type Conditions

DS Receive

Personal

Data

Concerning

him or her

DC Provide

Personal

Data

Provided by

Data Subject

The third step in the semantic parametrization is the

phrasing of RNLS, which are defined to have exactly

one actor, one action and one or more objects. More

complicated goals are split into multiple RNLS with

references to each other. A network of dependencies

among the RNLS of Art. 20 and referenced articles is

shown in Figure 2.

As the final result of the process described by

Breaux, we obtained a semantic model representation.

This semantic model consists of atomic elements, cat-

egorized as rights or obligations for the data subject

or the data controller. Analyzing each of these ele-

ments, we identified the following list of information

requirements for the data controller:

• personal data concerning the data subject

• processing based on consent

• processing based on explicit consent

• processing based on a contract

• special categories of personal data

• erasure date

• processing in the public interest

Note that there are two information items pro-

cessing based on consent and the stronger condition

processing based on explicit consent. This reflects

the distinction the regulation makes between personal

data and special categories of personal data, which are

sensitive in relation to fundamental rights and free-

doms. The special nature of the data has to be pointed

out when obtaining consent.

5 DATA PORTABILITY SERVICE

DEFINITION

In this section, we first briefly explore the concept of

platform-independent service design, which we resort

to for the definition of our data portability service.

We then specify the generalized information model

from which we intend to extract the information items

we identified in section 4. Lastly, we define the data

portability service as a business process.

5.1 Service-orientation

A service is the behavioral description of a system

without limitations on its internal structure (Almeida

et al., 2003). In a setting as diverse as the collection

of personal information, this concept is particularly

well-suited for the data portability requirements. An

example for the platform-independent service design

is given by (Almeida et al., 2003) and displayed in

figure 3 as systematic design approach.

One milestone is the platform-independent ser-

vice design. This phase contains the platform-

independent service logic by using service compo-

nents and abstract-platform definitions. Especially,

the portability requirements of the characteristics of

the platform have to be taken into consideration.

The last milestone is the platform-specific ser-

vice design which contains platform-specific service

components and a concrete platform definition. In

case the abstract platform definition does not differ

A Service Definition for Data Portability

171

Figure 1: Semantic parametrization with additional steps.

Figure 2: Network of RNLS of Art. 20.

Figure 3: Platform-independent Service Description

(Almeida et al., 2003).

from the platform chosen, the transfer from platform-

independent to platform-dependent service design can

be done easily.

5.2 Information Model

For the development of the information model as a

basis for the data portability service, the platform-

independent service design (Almeida et al., 2003) is

used. Thus, an information model should describe

a service which follows the systematic approach of

platform-independent service design. In this case, the

service definition contains the definition of necessary

information to fulfill data portability GDPR Art. 20

and the definition of how this data can be gathered

from an abstract point of view.

Besides the abstraction level, the information model

focuses on business objects which are defined as

“A business object is defined as a passive el-

ement that has relevance from a business per-

spective.” (The Open Group, 2013)

According to (Hess et al., 2006), there should be a

business object type distinction between fast changing

business objects (transaction data) and slowly chang-

ing business objects (master data). An example for

master data is customer data like the name, address,

date of birth, etc. as it is rarely updated by the cus-

tomer. Transaction data is orders and invoices, as this

data is changing and growing steadily - depending on

the users’ behaviour. For the fulfillment of GDPR Art.

20, a distinction of master data and transaction data

of business objects is necessary as it contains differ-

ent efforts of extracting the information to fulfill the

requirements (Lewinski et al., 2018).

Considering the abstraction level and business ob-

ject definition, the information model is displayed in

Figure 4.

Figure 4: Data Gathering Service accessing Data Portability

Information Model at Business Subject.

• Business Subject: A Business Subject is a type

of business object which is stored as master data.

Examples for a Business Subject are product or

customer records. In this paper, Business Sub-

jects which are directly related to a person, such

as a customer’s record, are in focus. We regard

business subject data as master data.

• Business Entity: A Business Entity is a type of

business object which is created by and directly

connected to a Business Subject. In other words

transaction data (e.g. invoices, orders).

• GDPR Data Gathering Service: This service is

an integration layer which requests data sources

of the required information for the data transfer.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

172

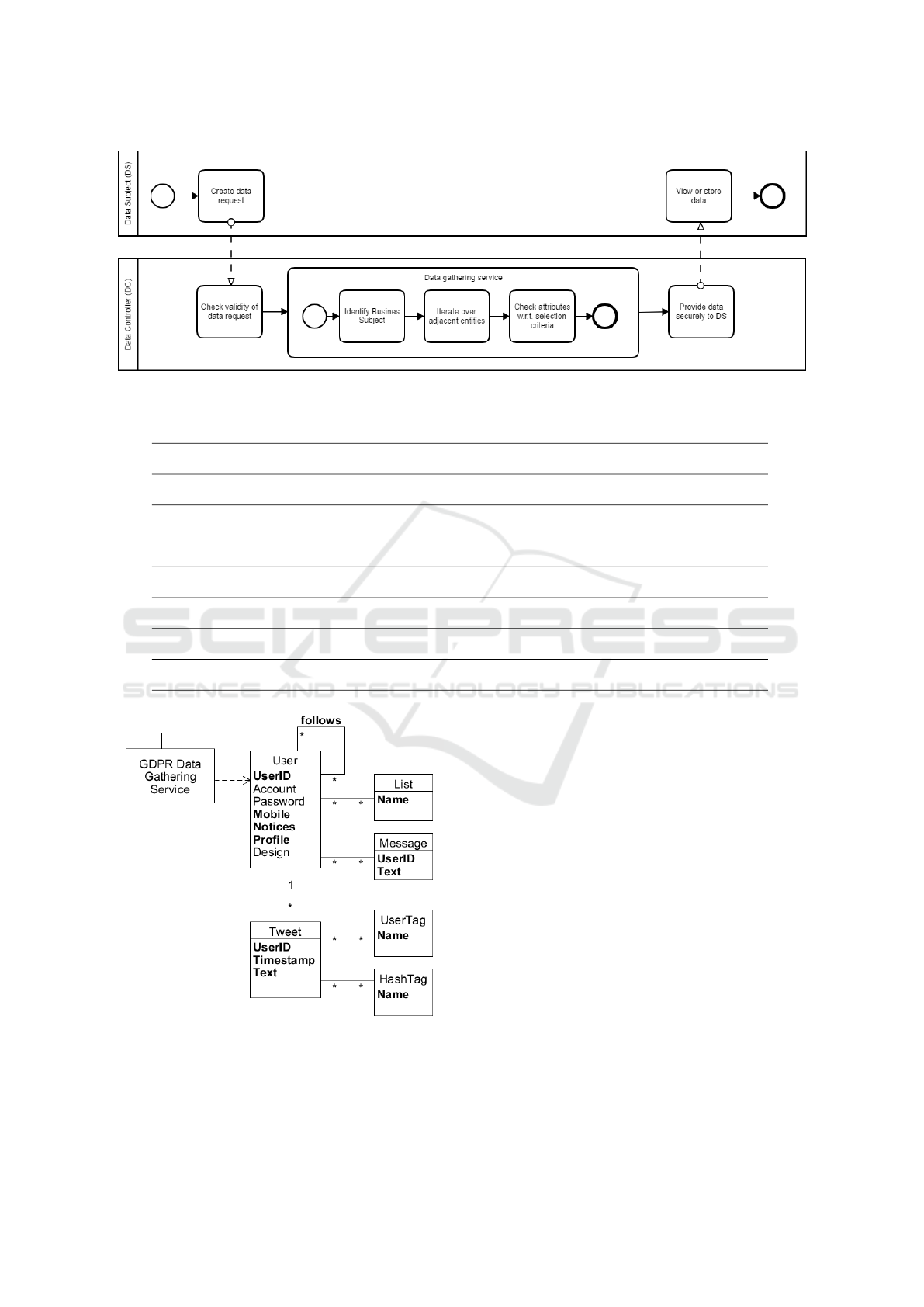

5.3 Data Portability Service

The data portability service is described by a process,

which is displayed in Figure 5 and explained in this

section.

The first step is the creation of a request by the

data subject. Then, this request has to be verified

by the data controller. Therefore, the request will be

valid if it is created on the basis of the GDPR and not

under country-specific regulations. Further, the data

subject has to be authenticated and their request au-

thorized.

If the request is valid, the next step is to iden-

tify the relevant data. For this purpose, the GDPR

data gathering service collects all relevant data. This

data gathering subprocess starts at the business sub-

ject which is related to the requester. Further, it iter-

ates over adjacent business entities. Finally, each en-

tity attribute is verified with respect to the relevance

for complying with data portability (Section 4).

After summarizing the data gathering subprocess

output, the resulting data needs to be returned se-

curely to the requester. With the submission of the

data report to the data subject, the data controller fin-

ishes its required work to comply with data portability

according to Art. 20 of the GDPR.

6 TWITTER EXAMPLE

To ensure the understanding of the proposed process,

we exemplify the approach with the help of the so-

cial network Twitter. In Figure 6, we show how the

GDPR Data Gathering Service accesses the Twitter

data model (Neppelenbroek et al., 2011) at the User

element, which is its root node.

In this case, the business subject is the class User

and the relevant business entities are List, Message

and Tweet. The latter one refers further to the business

entities HashTag and UserTag.

The process starts with a request by a user who

demands a report according to data portability GDPR

Art. 20. In the case of Twitter, this is most done

within an online account.

The next step by the data controller is to verify

this request. Thus, the user has to be authenticated

and the request authorized. In the case of an online

account, the user is already authenticated. In other

cases, the controller might ask for different modes of

authentication.

After verifying the request, the data controller has

to gather the required data to comply with data porta-

bility. Therefore, the data gathering service starts at

the business subject of the identified user. With the

list of properties from section 4, the attributes of User

are checked. UserID, Mobile, Notices and Profile are

identified as relevant for Art. 20 (shown in bold font

in Figure 6). Then, we iterate over the adjacent enti-

ties, i.e. other Users (that are being followed), Lists,

Messages, Tweets and so on. For each entity the crite-

ria from Section 4 are checked again. Combining all

this information yields the data that has to be trans-

ferred to the data subject.

Finally, the data report of the user’s provided in-

formation is returned securely to the data subject. In

the case of Twitter, this is done as a download link for

an authenticated account.

Now, the data subject can use this report for

switching to another data controller or as overview of

the information she provided to Twitter.

7 EVALUATION

For the evaluation of the service for data portability

and the underlying information model, seven expert

interviews were conducted. An overview of the inter-

viewees is displayed in Table 2.

Each interview started with an introduction of the

interviewee and the problem domain. To ensure the

expert’s understanding, an example for the service in-

stantiation was given. Then, the experts were asked to

evaluate the underlying information model according

to Lindland’s criteria (Lindland et al., 1994).

The first quality criterion is the syntactic quality

which discusses the realization of the modeling lan-

guage used within the model. Next, the semantic

quality describes the validity and completeness of the

model with respect to the problem domain. Finally,

the pragmatic quality is about the interpretation of the

model by the stakeholders and the objective of com-

prehensibility.

After the discussion of the information model’s

quality, the experts were asked open questions re-

garding the usage and application within the service

we described. After each interview, the information

model was adjusted according to the reasonable en-

hancements or changes suggested by the experts. The

updated information model was then used in the fol-

lowing expert interview. Using this procedure, the

service definition was developed iteratively.

The following paragraphs summarize the most im-

portant interview outcomes.

How do you evaluate the syntactic, semantic

and pragmatic quality of the information model?

Regarding the information model, the syntactic

and semantic quality improved iteratively as the ad-

dressed suggestions were added to the information

A Service Definition for Data Portability

173

Figure 5: Process of a Data Portability Request.

Table 2: Overview of Interviewees.

ID Current profession Company size Industry

1 Cyber Security Portfolio Manager large enterprise Industrial Manufacturing

2 Head of IT Strategy large enterprise Industrial Manufacturing

3 Co-Founder Compliance Tool Start-Up IT Service & Consulting

4 Corporate Data Privacy Officer large enterprise Industrial Manufacturing

5 Cyber Security Architect large enterprise Industrial Manufacturing

6 Head of Sales for Privacy Management Tool SME IT Service & Consulting

7 Business Intelligence (2) large enterprise Finance

Figure 6: Data Gathering Service applied to the Twitter data

model (information to be extracted in bold font).

model. In the end, the modeling language, syntax

and the validity and completeness with respect to the

problem domain were rated as good. Especially the

distinction between master and transaction data was

mentioned as advantage by experts 1, 3 and 6. An in-

teresting point mentioned by interviewees 2 and 6 is

the advantage regarding the abstraction level as they

agree to the point that a more detailed information

model would not be platform independent. Thus, the

service definition from section 5 is suitable. However,

the abstraction level was regarded as disadvantage to

the pragmatic quality. Due to missing implementation

details, experts 1, 2, 3 and 4 refer to the problem that

it is hard to understand how to take advantage and

realize the information model. Nevertheless, some

experts (5, 6, 7) already mentioned implementation

ideas, e.g. to enhance the Electronic Data Interchange

(EDI) with a plausibility check or connect a query to

the Data Warehouse.

What do you think about the feasibility of a

data gathering service for data portability automa-

tion?

With respect to the application of the data porta-

bility service, the interviewees 2, 3 and 7 recommend

the usage of this service for a greenfield approach

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

174

or in data-driven companies, e.g. social media net-

works. They mention an issue with complex infras-

tructure which would make it difficult to incorporate

an automated procedure for a data portability service.

Notwithstanding, all experts consider the information

model as useful guidance for the application of such

a service. As already mentioned above, the abstrac-

tion level was on the one hand seen as advantage, as it

summarizes the important facts necessary for comply-

ing with data portability, but on the other hand it was

categorized as disadvantage since implementation de-

tails are missing. Further, expert 3 recommends a de-

tailed description of data portability with respect to

one industry. This is one enhancement idea for fur-

ther discussion, as we will discuss in section 8. Inter-

viewees 1, 2, 6 and 7 point out the issue of identify-

ing where the required data is stored. Existing com-

plex IT landscapes or multiple Data Warehouses ham-

per the identification of data location. Thus, the data

flow mapping cannot be done easily, but is required

to comply with the GDPR. For companies with this

issue it is more difficult to apply the data portability

service as described.

How are you handling data portability re-

quests?

According to the experts 1, 2, 4, 5 and 7, they are

managing the requests manually as there are few in-

coming requests for data portability within their com-

pany. Further, there are no existing automated solu-

tions available which can handle their complex infras-

tructure.

8 CONCLUSION & OUTLOOK

In this paper, we have applied the process of semantic

parametrization in order to extract 7 specific informa-

tion for Art. 20 of the GDPR, answering RQ1 from

Section 1.

We then specified a platform-independent service

to respond to data portability requests. The service

makes use of a generalized information model and

takes into account the information requirements that

were identified. This answers RQ2.

To evaluate the usefulness and applicability of our

approach, we conducted 7 expert interviews. The

experts confirmed that a service definition can con-

tribute to the implementation of data portability. In

its current abstract form, it serves as a model to guide

the execution of data portability requests or even as

guidance for implementing an automated solution.

However, according to the experts, economic via-

bility of automated portability largely depends on the

type of business. The companies in our interiews have

to comply with the GDPR and therefore fulfil Art.

20 as well, but since they operate in a B2B context

(industrial and financial sector) or provide services

for SMEs, they are not faced with massive amounts

of data subject requests. This constitutes a limita-

tion of this work, since representatives of companies

whose business models rely heavily on personal infor-

mation were not part of this study. Some companies,

like Facebook and Google, have already implemented

automated solutions to answer data subject requests.

Experts who were involved in these efforts could pro-

vide valuable advice to companies with less public ex-

posure.

The service we defined aligns with current pri-

vacy engineering frameworks, since it addresses the

enhanced requirements in the soft privacy or privacy

by policy area. Definitions and good practices for ful-

filling these requirements can support developers in

implementing compliant architectures.

Further comments from our experts mentioned

that data subjects themselves are generally unaware of

the right to data portability and hence, requests typi-

cally refer to the right of access (Art. 15). Data sub-

jects also lack the knowledge what they have to pro-

vide in order to start a successful data subject request.

Having specified and evaluated a service for data

gathering in compliance with Art. 20 GDPR, we

acknowledge further possible directions of work.

Firstly, the approach could be extended to other ar-

ticles of the GDPR regarding the exercise of data sub-

ject rights. Due to the explicit references in Art. 20

we covered Art. 17 (right to erasure), as well as Art.

6 and Art. 9 (legal bases and preconditions for pro-

cessing special categories of personal data).

Secondly, industry-specific solutions or technical

implementations could be investigated. Such solu-

tions exist in deregulated utilities markets, where con-

sumers port their meter numbers from one utilities

provider to another, and are being developed for sim-

plified data models in social media (Google et al.,

2018). Further studies could investigate the develop-

ment and reasoning of the existing solutions by so-

cial media companies. Another approach led by Tim

Berners-Lee is called Solid, where the goal is to ex-

clusively store personal data in a personal data store.

Applications built on top of Solid never collect per-

sonal data themselves, but are granted access to sub-

sets of this data.

In any case, we expect the importance of data

portability to increase as awareness for the flexibility

it allows in the usage of services gains more attention

among data subjects.

A Service Definition for Data Portability

175

REFERENCES

Allen, T. (2018). ICO issues its first GDPR fine.

https://www.v3.co.uk/v3-uk/news/3063194/ico-

issues-its-first-gdpr-fine.

Almeida, J. P., Van Sinderen, M., Pires, L. F., and Quar-

tel, D. (2003). A systematic approach to platform-

independent design based on the service concept. In

Proceedings - 7th IEEE International Enterprise Dis-

tributed Object Computing Conference, pages 112–

123.

Article 29 Data Protection Working Party (2017). Guide-

lines on the right to data portability. April, pages 1–

11.

Bistolfi, C., Scudiero, L., Bistolfi, C., and Scudiero, L.

(2016). Bringing your data everywhere in the Internet

of ( every ) Thing : a legal reading of the new right

to portability. In 30th International Conference on

Advanced Information Networking and Applications

Workshops, pages 10–13.

Breaux, T. D., Vail, M. W., and Ant

´

on, A. I. (2006). To-

wards regulatory compliance: Extracting rights and

obligations to align requirements with regulations.

Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on

Requirements Engineering, pages 46–55.

De Hert, P., Papakonstantinou, V., Malgieri, G., Beslay, L.,

and Sanchez, I. (2017). The right to data portability

in the GDPR: Towards user-centric interoperability of

digital services. Computer Law and Security Review.

Deng, M., Wuyts, K., Scandariato, R., and Wouter, B. P.

(2011). A privacy threat analysis framework: support-

ing the elicitation and fulfillment of privacy require-

ments. Requirements Engineering, 16(1):1–27.

European Union (2016). Regulation 2016/679 of the Eu-

ropean parliament and the Council of the European

Union.

Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Microsoft (2018). Data

Transfer Project Overview and Fundamentals. Tech-

nical report, DTP Project.

G

¨

urses, S. and Del Alamo, J. M. (2016). Privacy Engi-

neering: Shaping an Emerging Field of Research and

Practice. IEEE Security and Privacy, 14(2):40–46.

Hess, A., Humm, B., and Voß, M. (2006). Regeln f

¨

ur ser-

viceorientierte Architekturen hoher Qualit

¨

at. Infor-

matik Spektrum, 29:395–411.

Kalloniatis, C., Kavakli, E., and Gritzalis, S. (2008). Ad-

dressing privacy requirements in system design: The

PriS method. Requirements Engineering, 13(3):241–

255.

Lewinski, Brink, S., and Wolff, A. (2018). BeckOK Daten-

schutzR - DS-GVO Art. 20. beck-online.

Lindland, O. I., Sindre, G., and Solvberg, A. (1994). Under-

standing quality in conceptual modeling. IEEE soft-

ware, 11(2):42–49.

Microsoft (2009). The STRIDE Threat Model.

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-

versions/commerce-server/ee823878(v%3dcs.20).

Neppelenbroek, M., Lossek, M., and Janssen, R. (2011).

Twitter: An Architectural Review. Scholars paper on

Software Architecture at Utrecht University.

Notario, N., Crespo, A., Martin, Y. S., Del Alamo, J. M.,

Metayer, D. L., Antignac, T., Kung, A., Kroener, I.,

and Wright, D. (2015). PRIPARE: Integrating privacy

best practices into a privacy engineering methodology.

Proceedings - 2015 IEEE Security and Privacy Work-

shops, SPW 2015, pages 151–158.

Solove, D. J. (2007). I’ve got nothing to hide and other mis-

understandings of privacy. San Diego l. Rev., 44:745.

Spiekermann, S. and Cranor, L. F. (2009). Engineering pri-

vacy. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering,

35(1):67–82.

The Open Group (2013). ArchiMate

R

2.1 Specification.

Tikkinen-Piri, C., Rohunen, A., and Markkula, J. (2017).

EU General Data Protection Regulation: Changes and

implications for personal data collecting companies.

Computer Law and Security Review.

Vanberg, A. D. and

¨

Unver, M. B. (2017). The right to data

portability in the GDPR and EU competition law: odd

couple or dynamic duo? European Journal of Law

and Technology, 8(1):1–22.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

176