Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu):

Development and Evaluation of a Self-assessment Instrument for

Teachers' Digital Competence

Mina Ghomi

1

and Christine Redecker

2

1

Department of Computer Science, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany

2

European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Seville, Spain

Keywords: Self-assessment, Teachers’ Digital Competence, DigCompEdu Framework.

Abstract: Based on the European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu), a self-

assessment tool was developed to measure teachers’ digital competence. This paper describes the

DigCompEdu reference framework, the development and the evaluation of the instrument, and analyses the

results of the study with 335 participants in Germany in view of the reliability and validity of the tool. To

determine internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha is considered for the entire instrument as well as separately

for the six competence areas. To investigate the validity, hypotheses based on groups with known attributes

are tested using the Mann-Whitney-U test and the Spearman rank correlation. As predicted, there is a

significant, albeit small, difference between STEM and non-STEM teachers, and computer science and non-

computer science teachers. Furthermore, there is also a significant difference between teachers with negative

attitudes to the benefits of technologies compared to those with neutral or positive attitudes. Teachers who

are experienced in using technologies in class have significantly higher scores, which further confirms the

validity of the instrument. In sum, the results of the analysis suggest that the survey is a reliable and valid

instrument to measure teachers’ digital competence.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Internet and digital technologies have become an

integral part of everyday life in the 21st century. It is

therefore imperative that all citizens develop digital

competence as a key competence of lifelong learning,

facilitating personal fulfilment and development,

employability, social inclusion and active citizenship

(Council of the European Union, 2018). The

European Digital Competence Framework

(DigComp) published in 2013 and revised in 2016

and 2017 describes the digital competence of citizens

(Ferrari, 2013; Carretero et al., 2017). European

member states have used the DigComp framework as

a reference framework, e.g. in Germany the

Kultusministerkonferenz (KMK) refined it for their

own framework for students' digital competence

(KMK, 2016). The need to equip citizens with the

corresponding critical and creative skills places new

demands on educators at all levels of education, who

must not only be digitally competent themselves, but

must also promote students' digital competence and

seize the potential of digital technologies for

enhancing and innovating teaching.

The European Framework for the Digital

Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu) published

in 2017 describes the digital competences specific to

the teaching profession (Redecker, 2017). This

framework is based on extensive expert consultations

and aims to structure existing insights and evidence

into one comprehensive model, applicable to all

educational contexts. To allow educators to get a

better understanding of this framework and to provide

them with a first assessment on their individual

strengths and learning needs, an online self-

assessment instrument has been developed, freely

accessible in a number of languages.

The aim of this study is to validate the German

version of this instrument for teachers in primary,

secondary and vocational education. Once validated,

the self-assessment tool will help teachers to reflect

on their digital competences and identify their need

for further training and professional development.

Ghomi, M. and Redecker, C.

Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu): Development and Evaluation of a Self-assessment Instrument for Teachers’ Digital Competence.

DOI: 10.5220/0007679005410548

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 541-548

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

541

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

According to Redecker (2017) the European

Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators

(DigCompEdu) details 22 educator-specific digital

competences organised in six areas.

Applied to the context of school education Area 1

Professional Engagement describes teachers'

efficient and appropriate use of technologies for

communication and collaboration with colleagues,

students, parents and external persons.

The core of the DigCompEdu framework is

represented by the areas 2 to 5, in which technologies

are integrated into teaching in a pedagogically

meaningful way. Area 2 Digital Resources focuses on

the selection, creation, modification and management

of digital educational resources. This also includes

the protection of personal data in accordance with

data protection regulations and compliance with

copyright laws when modifying and publishing

digital resources. The third area (Teaching and

Learning) deals with planning, designing and

orchestrating the use of digital technologies in

teaching practice. It focuses on the integration of

digital resources and methods to promote

collaborative and self-regulated learning processes

and to guide these activities by transforming teaching

from teacher-led to learner-centred processes and

activities. Area 4 Assessment addresses the concrete

use of digital technologies for assessing student

performance and learning needs, to comprehensively

analyse existing performance data and to provide

targeted and timely feedback to learners. With Area 5

being centred on Empowering Learners the

framework emphasises the importance of creating

learning activities and experiences that address

students' needs and allow them to actively develop

their learning journey.

Area 6 (Facilitating Learners’ Digital

Competence) completes the framework by

highlighting that a digitally competent teacher should

be able to promote information and media literacy

and integrate specific activities to enable digital

problem solving, digital content creation and digital

technology use for communication and cooperation.

Each individual competence of the DigCompEdu

framework is described along six proficiency levels

(A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2) with a cumulative

progression, linked to the Common European

Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

Teachers at the first two levels, A1 and A2, have

started to use technology in some areas and are aware

of the potential of digital technologies for enhancing

pedagogical and professional practice. Teachers at

level B1 or B2 already integrate digital technologies

into practice in a variety of ways and contexts. At the

highest levels C1 and C2, teachers share their

expertise with peers, experiment with innovative

technologies and develop new pedagogical

approaches.

According to this approach, a teacher’s general

digital competences (as described in DigComp) is a

prerequisite for developing the teacher-specific

digital competences as described in DigCompEdu.

Further prerequisites are the teacher's subject-

specific, pedagogical and transversal competences.

Hence, DigCompEdu agrees with the TPACK

framework published by Mishra and Koehler in 2006,

which postulates that three knowledge areas -

technological, pedagogical and content knowledge -

need to be effectively integrated for teachers to use

digital technologies with added value in their

teaching. However, where TPACK falls short of

explaining how this connection is established,

DigCompEdu aims to identify pedagogical and

professional focus areas for the integration of

technology into teaching and professional practice.

To be able to supply such detail and still be applicable

across all subjects and in a continuously changing

technological landscape, the focus of DigCompEdu is

clearly on the pedagogical element. DigCompEdu

describes how technological competence (as

described in DigComp) and subject-specific teaching

competence (as described by curricula) can be

pedagogically integrated by teachers to provide more

effective, inclusive, personalised and innovative

learning experiences to students. DigCompEdu

furthermore acknowledges that to transform

education in such a way a wider approach, including

the professional environment and the integration of

learning into the overall social and societal context is

needed. Areas 1 and 6 cover these aspects.

3 METHODOLOGY

Based on the DigCompEdu framework and its

proficiency levels an online self-assessment tool was

developed that allows teachers to assess their digital

competence. The tool development was guided by

three principles: (i) to condense and simplify the key

ideas of the framework, (ii) to translate competence

descriptors into concrete activities and practices, and

(iii) to offer targeted feedback to teachers according

to their individual level of competence for each of the

22 indicators. Following these principles, 22 items

were developed, so that each competence is

represented by one item. Each item consists of a

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

542

statement describing the core of the competence in

concrete, practical terms, and 5 possible answers,

which are cumulatively structured and mapped onto

the proficiency levels. The teacher is asked to select

the answer that best reflects his or her practice.

Instrument Development

The instrument development followed an iterative

process of expert consultations, pre-piloting and item

revision. A first version of the self-assessment

instrument using a frequency scale for answer options

was made available via EUSurvey, an online survey

tool, in March 2018. This English-language version

was tested, by independent experts, with 160 English

teachers in Morocco (Benali, Kaddouri and

Azzimani, 2018). The data analysis showed an

excellent internal consistency for the whole

instrument, with a Cronbach's alpha of .91. In April

2018, the German translation was tested by 22

teachers in Germany and evaluated with the help of

comment fields as well as orally afterwards.

However, these trials also revealed that some

answer options were not selected by users and the

feedback collected on the user experience indicated

that some items did not meet user expectations. The

subsequent consultations with 20 experts (researchers

and teachers) in a workshop in May 2018 and through

involvement of the DigCompEdu community led to a

collaborative redesign of the answer options. As a

first step, the 20 subject-matter experts supervised the

item revision process by discussing the relevance and

representativeness of the items to the framework.

After each revision made, all items were made

available to the DigCompEdu community on the

European Commission website so that the community

members, consisting of interested teachers, lecturers,

researchers and experts, could comment on the items

and test the survey. The review process was repeated

until no more comments or remarks were made.

In October 2018 a new version was made

available in English and German. The main changes

with respect to the early version published in March

2018, concern the creation of different versions for

different educator audiences and the stronger

alignment of the answer scale with the DigCompEdu

framework progression. The answer options were

more adapted to the descriptors and the progression

foreseen in the DigCompEdu framework. The experts

agreed that, as in the previous version of the tool, each

competence should continue to be represented by

only one item and that the total digital competence

should then consist of all 22 items. Therefore, in some

cases, a choice had to be made between different

aspects crucial to a given competence. However, care

was taken to select the most generic and basic

concept. For example, for competence 2.3 Managing,

protecting, sharing, it was decided to focus on data

protection, rather than on copyright rules or the use of

shared content repositories.

Similarly, the framework's competence

progression in six stages was transformed into a five-

point-scale, which was guided by considerations

about the different implementation stages expected to

be prevalent among current teachers. As the

progression in the framework, the self-assessment

tool assumes that digital competence development

comprises the following stages: no use - basic use -

diversification - meaningful use - systematic use -

innovation.

In some transpositions of the framework into the

self-assessment tool, the categories of meaningful and

systematic use were merged, as it was deemed

difficult for users to differentiate between the two

options. In other cases, where it was expected that

current usage patterns were unlikely to yet display

innovative strategies, the highest competence level,

C2, was left out. Sometimes both strategies were

combined to allow users more choices at the lower

end of the competence range by splitting the "no use"

category into two answer options: a) no experience

with the practice at hand and b) experience with the

practice, but not with using digital technologies

within the practice.

The resulting instrument employs five answer

options for which points ranging from 0 to 4 are

scored. In the feedback report generated, the total

score - ranging from 0 to 88 points - is mapped onto

the six different proficiency levels. For the initial

allocation of score intervals to proficiency levels, the

mapping of answer options onto the proficiency scale

was taken as an orientation. Based on the expert

consultation, the allocation of the total score to the six

levels was discussed and adjusted.

Additionally, the feedback report indicates scores

per area, in order for teachers to determine their

relative areas of strength and their specific needs for

further training. For these, only an indicative

proficiency level was provided as a first orientation.

The instrument also included items addressing

demographic information and information on school

type and equipment, teaching activities and attitudes

towards digital technologies.

3.1 Sample

From 24 September until 29 November 2018, data of

335 teachers were collected online via EUSurvey. At

three German-language conferences during the same

period, posters and flyers were used to promote

Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu): Development and Evaluation of a Self-assessment Instrument for Teachers’ Digital

Competence

543

participation in the online self-assessment survey. In

general, the participation in the study was voluntary.

No rewards or incentives were offered.

In total, 168 (50.1 %) women and 146 (43.6 %)

men took part in the survey; 21 (6.3 %) persons

preferred not to report their gender. The age of 90.4

% of the participants was between 25 and 59 years.

10.1 % of teachers teach in primary schools, 25.4 %

in "Gymnasium" (one type of secondary school) and

the rest in other types of schools. 134 (40 %) of

participants teach STEM subjects, of which 41 (12.2

%) are computer science teachers.

Participating teachers have indicated how many

years they have been teaching and how many years

they have been using digital technologies in class

(Table 1). In total, 24.5 % have been using digital

technologies in class for more than 10 years. Of these,

80.95 % are STEM teachers.

In addition, a multiple-choice question was asked

as to which digital tools they were already using with

their students in class. Presentations (89.9 %),

watching videos or listening to audios (87.5 %),

online quizzes (59.4 %) and interactive apps (54.3 %)

were the most frequently mentioned. On average,

teachers use 4.2 digital tools in class.

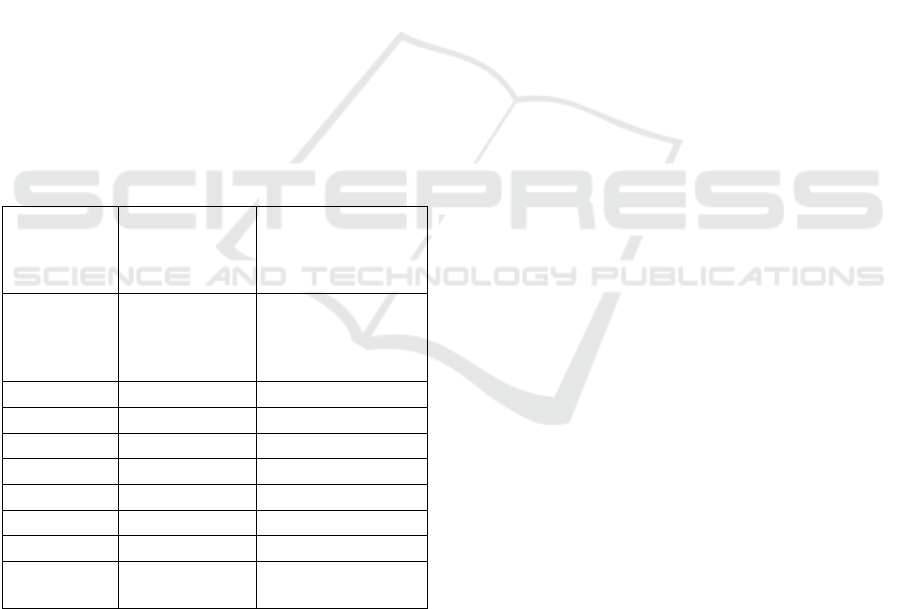

Table 1: Professional and media experience in class.

How many

years have you

been teaching?

How many years

have you been using

technologies in

class?

I have not

used digital

technologies

in class yet

- 1,2 %

Less than 1 20,6 % 21,2 %

1 - 3 9,9 % 18,5 %

4 - 5 8,4 % 13,10 %

6 - 9 8,4 % 16,7 %

10 - 14 14,9 % 13,1 %

15 - 19 14,9 % 8,1 %

20 or more 19,1 % 3,3 %

I do not

want to say.

3,9 % 4,8 %

3.2 Data Analysis

A number of quantitative research methods were

applied to establish evidence for the validity and

reliability of the instrument. We assessed the whole

instrument with 22 items and each of the six

competence areas for internal consistency using

Cronbach's alpha reliability technique. To test the

validity of the instrument we used the known-groups

method (Hattie and Cooksey, 1984). The method

states that as a criterion for validity, test results should

differ between groups which - based on theoretical or

empirical evidence - are known to differ. We

therefore formulated hypotheses about the different

results expected to be obtained by sub-groups of the

sample with known attributes, which, according to

empirical evidence, differ as concerns their level of

digital competence (hypotheses 1a, 1b, 4). We

furthermore investigated hypotheses based on

conceptual assumptions underlying the DigCompEdu

framework (hypotheses 2, 3a, 3b):

Hypothesis (1a): STEM teachers have a higher

total test score than teachers who do not teach STEM

subjects.

Hypothesis (1b): Computer science teachers score

better in the test than teachers who do not teach

computer science.

Hypothesis (2): The more years a teacher already

uses digital technologies in teaching practice, the

higher the teacher's digital competence and thus the

overall test result.

Hypothesis (3a): The number of digital tools used

in teaching correlates with the digital competence of

the teacher, i.e. with his or her overall score in the test.

Hypothesis (3b): Teachers who use more than the

average digital tools in class score better in the test

than teachers who use up to 4 different tools.

Hypothesis (4): Teachers with a negative attitude

towards the benefits and use of digital technologies in

teaching will have a lower overall score in the test

than teachers with a positive or neutral attitude.

To further support the validity of the instrument

participants were asked to assess their digital

competence as teachers based on the six proficiency

levels (A1-C2). We expect a high correlation between

the self-assessed level and the level calculated on the

basis of the total score.

To test the hypotheses, the Mann-Whitney U test

was used and the Spearman's rank correlation

coefficients were calculated.

4 RESULTS

A total of 88 points can be achieved. Looking at the

results of this study, the median of the total score is

45 points (minimum 11 points and maximum 88

points). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that

these data deviate significantly from the normal

distribution and are therefore not normally

distributed.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

544

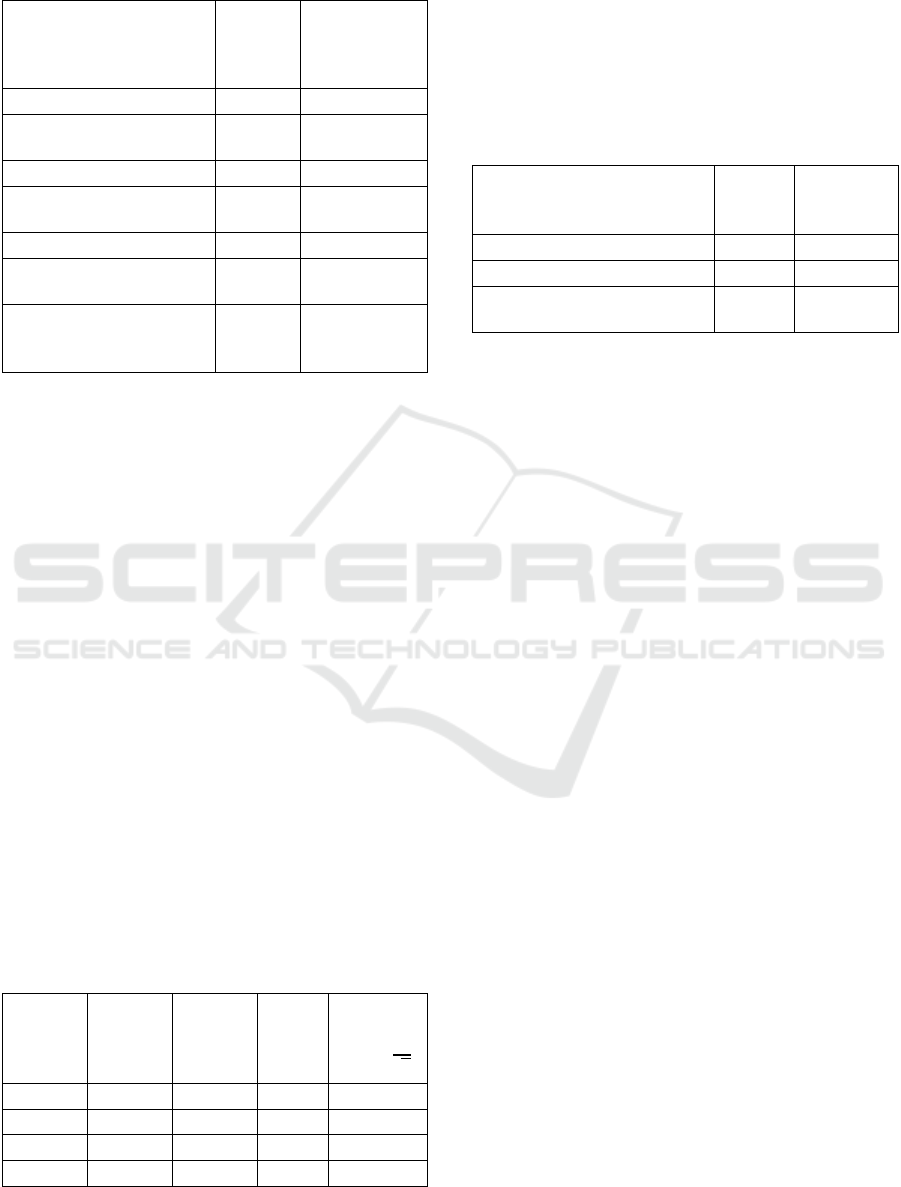

Table 2: Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for internal

consistency.

Number

of items

Internal

Consistency

(Cronbach's

alpha)

Whole instrument 22 .934

Area 1: Professional

Engagement

4 .779

Area 2: Digital Resources 3 .687

Area 3: Teaching and

Learning

4 .798

Area 4: Assessment 3 .690

Area 5: Empowering

Learners

3 .752

Area 6: Facilitating

Learners' Digital

Competence

5 .823

The entire instrument with 22 items has an

excellent internal consistency with a value of .934 for

Cronbach's alpha. Table 2 lists Cronbach's alpha by

area, which range from .687 to .823. According to

George and Mallery (2003), this range is considered

to be acceptable to good with the exception of area 2

and 4, which are lower than .7 and therefore

questionable. Cronbach's alpha of area 4 would

increase from .69 to .716 and the Cronbach's alpha of

the whole instrument would increase from .934 to

.935, if the second item of area 4 (item 4.2) was

omitted. This is the only item that, if omitted, would

lead to an increase of the internal consistency. Also

the Corrected Item-Total Correlation of only this item

is conspicuously low (.413), but nevertheless

acceptable (Gliem and Gliem, 2003). For all other

items the Corrected Item-Total Correlation is above

.50.

To test our hypotheses (1a, 1b, 3b, 4) we used the

Mann-Whitney U test, a nonparametric test which

does not require the assumption of the data being

normally distributed (Mann and Whitney, 1947).

Table 3 summarizes the results of the Mann-Whitney

U test and the respective effect size.

Table 3: Results of Mann-Whitney U test.

Hypo-

thesis

U p

(asymp.

sig. (2-

tailed))

z

Calculated

effect size

r=

√

1a 10889.5 .003 -2.97 .16

1b 3933.5 .000 -3.60 .20

3b 3896.0 .000 -11.27 .62

4 10085.5 .000 -4.347 .24

In order to test the hypotheses regarding the

expected correlations, we have calculated Spearman's

rank correlation coefficients (Spearman's rho), a

nonparametric and distribution-free rank statistic, to

measure the strength of the association (Hauke and

Kossowski, 2011). Table 4 shows the results for

Spearman's rho.

Table 4: Results of Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

Hypothesis p

(sig. (2-

tailed))

Spearman's

rho

r

2 .000 .32

3a .000 .68

Self-assessment compared to

level determined by total score

.000 .71

Our first hypothesis predicted that STEM teachers

would score higher in the test than teachers who do

not teach STEM subjects. We found a significant

difference between STEM teachers compared to

teachers of other subjects. The effect size of r = .16

indicates a weak effect. The calculation of the

quartiles has shown that the first quartile, the median

and the third quartile of the STEM teachers (Q

= 40,

median = 47, Q

= 58, n

= 134) are clearly higher

and over a shorter range than those of the non-STEM

teacher (Q

= 32, median = 42, Q

= 55, n

=

201). We then considered the computer science

teachers separately and compared their overall results

(Q

= 43.5, median = 52, Q

= 64.5, n

= 41) with

those of the non-computer science teachers (Q

= 34,

median = 43.5, Q

= 55, n

= 294). Again, we

found a significant difference with a weak effect size

(r = .2).

To test hypothesis 2, we examine whether the

number of years in which teachers have had

continuous experience and engagement with the use

of technology in teaching practice is related to their

digital competence and thus to their total score in the

test. We found a positive correlation of medium

strength (r

= .32), which is statistically significant.

We furthermore expected (hypothesis 3a) the

number of digital tools used in teaching to correlate

with the teacher's digital competence and thus with

his total score in the test. The analysis shows that this

correlation is significant at a .01 level and Spearman's

rho is r

= .68. According to Cohen (1988), this value

is indicative of a strong correlation. Likewise, for our

hypothesis 3b, which states that teachers who use

digital tools more than average, i.e. who use 5 to 9

different digital tools in class, achieve a higher overall

score than teachers who use 0 to 4 tools, we have

found a significant difference with a strong effect size

Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu): Development and Evaluation of a Self-assessment Instrument for Teachers’ Digital

Competence

545

(r = .62). In this case, STEM teachers were not

dominant in

the group of more than 4 tool users and

only slightly overrepresented when compared to non-

STEM teachers: In total, there were 146 teachers

using more than 5 digital tools, 71 (48.63 %) of them

were STEM teachers.

Hypothesis 4 uses data collected across seven

questions on participants' general attitudes towards

technology and their self-efficacy in using of digital

technologies for general purposes, using a five-point

Likert scale (from "strongly disagree" to "strongly

agree"). To test hypothesis 4, we divided participants

into two groups: Teachers who responded negatively

to at least one of the seven questions are compared to

the remaining teachers. The Mann-Whitney U test

revealed that there is a significant difference between

the two groups. However, the effect size is .24, which

indicates a weak effect.

The comparison between the digital competence

assessed by the participants themselves and the level

determined by the total score showed a strong,

positive Spearman rank correlation, which is

statistically significant (r

= .71, p = .000). A closer

look at the frequencies of self-assessments that are

equal to, underestimating or overestimating the

calculated level shows that 55.5 % and thus the

majority of the participants underestimated

themselves. Only one third of the participants

assessed themselves according to the level calculated

by the total score. 11 % judged themselves to be

better.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that the self-

assessment instrument developed is reliable and valid

and thus suitable for measuring teachers' digital

competence.

As concerns the reliability of the instrument, we

observe an excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's

alpha) of the instrument. However, this finding

should not be taken to imply that teachers’ digital

competence may be considered a unidimensional

construct (Gliem & Gliem, 2003, p. 87). Future

research should investigate the internal structure and

determine the dimensionality.

Compared to the pre-piloting of the English

version with 160 teachers (Benali et al., 2018), the

internal consistency has increased even further after

the items have been revised. Nevertheless, the

analysis has shown that two areas have a lower

internal consistency. In particular, one item would

slightly increase the internal consistency of the

instrument by being omitted. Initial considerations of

the research team suggest that both the item and the

competence differ from the majority of other items

and competences by the fact that they do not focus on

practical digital tool use, but on the interpretation of

data. Additionally, since the competence as it is

described in the framework, presupposes a high level

of digital tool use, for the questionnaire a version with

a slightly less pronounced technological focus was

opted for. To better understand the consequences to

be drawn from the fact that the removal of this item

would lead to an increase in the internal consistency

of the tool it is proposed to involve an expert panel in

a new item revision process, including the reflection

on the focus and scope of the corresponding

competence as it is described in the framework.

When investigating the validity of the instrument,

all hypotheses could be confirmed, suggesting that

the tool is a valid means of ascertaining teachers'

digital competence.

The expectation that STEM-teachers and

especially computer science teacher score higher than

non-STEM and non-computer science teachers was

based on previous studies showing significant

differences between STEM and non-STEM teachers

(e.g. Jang and Tsai, 2012; Endberg and Lorenz, 2017)

and further supported by the fact that due to school

curricula require computer science teachers to

extensively use digital technologies in class. Our

dataset not only confirms the frequent and long-

standing use of technologies in STEM teaching

practice, but also our study hypotheses that these

practices lead to a higher level of digital competence,

as it is measured by the DigCompEdu self-assessment

instrument. STEM and computer science teachers do

have a significantly higher total score in our test.

However, the effect size is weak, which can be

explained by the fact that the DigCompEdu

framework does not focus on technical or general

digital skills. It explicitly puts pedagogical and

methodological considerations that are specific for

teaching processes at the core of the framework,

spelling out how these are transformed when digital

technologies are used. So this effect should not be too

high. Otherwise either the framework or the

instrument developed would put an overly high

importance on STEM-specific or technical digital

skills and not adequately apply to all subjects, which

would be contrary to the framework design. Another

reason for the weak effect size could be explained by

the results of the PISA 2015, which state that the

STEM subjects in Germany, in particular, still have

room for improvement in the way they use digital

technologies (Reiss et al., 2016).

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

546

The second hypothesis postulated a correlation

between the years of experience in using digital

technologies in education with the competence level

obtained. This hypothesis is based on the framework

assumption that digital competence improves with

digital practice, so that teachers who have had more

years of experience in using digital technologies in

teaching should be more fluent in doing so, and

therefore, overall, more digitally competent. The data

confirms this assumption; there is a positive

correlation of medium strength between the number

of years of experience in using digital tools in

teaching with the overall score obtained. However,

the vast majority of long-term technology users are

STEM-teachers, indicating that hypotheses 1 and 2

are interrelated. It is therefore difficult to attribute the

effect observed to either one or the other specific

characteristic considered in hypotheses 1 and 2.

Hypothesis 3a and 3b approaches the effect of

digital practice on digital competence from a slightly

different perspective, not looking at experience and

exposure over time, but at the diversity of digital

strategies employed. Since the DigCompEdu

framework suggests that the digital competence

improves as more and more different digital tools are

included in a reflective practice, if the instrument

correctly reflects the frameworks assumptions, there

should be a high correlation between the total score

achieved and the number of different digital

technologies used. Hence, hypothesis 3 tries to

capture one of the fundamental assumptions of the

DigCompEdu framework that it is the diversity of

digital strategies that contributes to raising educators'

digital competence.

When considering the diversity of digital tool use

in teaching, we obtain a high positive correlation

(hypothesis 3a). This means that teachers who use a

variety of tools more frequently have a significantly

higher total score. It is underpinned by the strong

effect size of the significant difference between the

groups of teachers who use above-average (5-9) and

less than average (0-4) tools in class (hypothesis 3b).

About half of the teachers who use more than 4 tools

are STEM teachers. Hence, this strong effect cannot

be attributed solely to subject profiles, but seems to,

in fact, confirm the assumption that digital

competence increases with the diversity of digital

tools employed. However, this finding is limited by

the fact that the quality or frequency of use of the

various digital tools was not surveyed.

The stipulation of hypothesis 4 is based on results

of previous studies, such as ICILS 2013, which have

shown that the confidence and positive attitude of

teachers towards the use of digital technologies is

linked to the perceived pedagogical value of the

technological tool and the frequency of use (Lorenz,

Endberg and Eickelmann, 2017; Huang et al., 2013;

Petko, 2012). Therefore, teachers with a negative

attitude towards the benefits and use of digital

technologies in teaching should have a lower overall

score in the test than teachers with a positive or

neutral attitude. The results show that this difference,

although with a weak effect size, is significant, which

is another indicator of the instrument's validity.

The fact that the expectations users had on their

competence level is significantly correlated to the

score obtained, with a positive and strong rank

correlation, suggests that the instrument also fulfils

this condition. However, more than half of the

participants consider themselves to be at a lower level

than the level determined by the total score. Possible

reasons could be, on the one hand, a lack of

information for the participants about the meaning of

the proficiency levels or the lack of competence to

assess oneself in this respect, or, on the other hand, a

not yet fully developed calculation of the proficiency

levels from the total score. Further studies and expert

consultations should shed more light on this effect.

In addition to the limitations already mentioned,

there are further limitations of the study that should

be considered. The data collection was not conducted

under a controlled setting. The survey was available

online for anyone to use, so that it is impossible to

ascertain that all participants are, in fact, teachers,

who truthfully filled in the survey. In addition, all

results are based on self-reported data that are known

to be subject to individual and cultural biases. When

assessing teachers' digital competence, for example,

it would also be useful to supplement teachers' self-

reports with knowledge-based tests, student

questionnaires or observation data. This could also

improve the measurement of the quality of the use of

digital technologies in teaching practice.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the DigCompEdu framework we developed

a self-assessment instrument for teachers' digital

competence. The aim of this study was to investigate

the reliability and validity of this instrument. The data

collected on the German version of the self-

assessment tool for teachers with this sample of 335

teachers suggests a high internal consistency. Future

work will consist of further increasing these by

discussing and adapting questionable items. In order

to verify the validity of the instrument, several

hypotheses about theoretically expected differences

Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu): Development and Evaluation of a Self-assessment Instrument for Teachers’ Digital

Competence

547

between subgroups of the sample were formulated

and confirmed by the analyses. From a conceptual

point of view, it was crucial that there are differences

between teachers who have many years of experience

with technologies in teaching or who already use a

variety of tools in practice. The existing but small

difference between STEM and non-STEM teachers or

computer science and non-computer science teachers

confirms that the instrument correctly represents the

key assumption of the DigCompEdu framework as a

framework applicable to all teachers and teaching

contexts. Teachers with more years of experience in

using technologies in teaching tend to have a

moderately higher score and teachers using a greater

variety of digital teaching strategies tend to have a

substantially higher score, indicating that the

instrument reflects the framework's assumption that

digital competence develops with experience and by

diversifying digital strategies. Despite a strong rank

correlation between the self-assessed level and the

level calculated from the total score, the future goal

should be to further increase this correlation.

The instrument provides a promising starting

point for the development of further DigCompEdu

assessment tools. To verify these findings for other

language versions and the contextual adaptations for

higher and adult education, similar studies should be

conducted with the different variants of the tool.

This tool gives teachers the opportunity (1) to

learn more about the DigCompEdu framework, i.e. of

what it means to be a digitally competent educator,

(2) to get a first understanding of their own individual

strength, and (3) to get ideas on how to enhance their

competences. Likewise, teacher trainers could

identify the needs and strengths of their CPD

participants and, e.g. select or design suitable training

courses. Prospectively, we plan to conduct studies to

further validate the instrument and thus also to

evaluate the suitability of the feedback. Especially in

individual feedback we see the potential to help the

educators to further develop their digital competence.

REFERENCES

Benali, M., Kaddouri, M., Azzimani, T., 2018. Digital

competence of Moroccan teachers of English.

International Journal of Education and Development

using ICT, 14(2).

Carretero, S., Vuorikari, R., Punie, Y., 2017. DigComp 2.1:

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with

eight proficiency levels and examples of use (No.

JRC106281). Joint Research Centre (Seville site).

Cohen, J., 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the

Behavioral Sciences, 2

nd

ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Council of the European Union, 2018. COUNCIL

RECOMMENDATION of 22 May 2018 on key

competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of

the European Union.

Endberg, M., Lorenz, R., 2017. Selbsteinschätzung

medienbezogener Kompetenzen von Lehrpersonen der

Sekundarstufe I im Bundesländervergleich und im

Trend von 2016 bis 2017. Schule digital–der

Länderindikator, 151-177.

Ferrari, A., 2013. DIGCOMP: A framework for developing

and understanding digital competence in Europe.

European Commission. JRC (Seville site).

George, D., Mallery, M., 2003. Using SPSS for Windows

step by step: a simple guide and reference.

Gliem, J. A., Gliem, R. R., 2003. Calculating, interpreting,

and reporting Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient

for Likert-type scales. Midwest Research-to-Practice

Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community

Education.

Hattie, J., Cooksey, R. W., 1984. Procedures for assessing

the validities of tests using the" known-groups" method.

Applied Psychological Measurement, 8(3), 295-305.

Hauke, J., Kossowski, T., 2011. Comparison of values of

Pearson's and Spearman's correlation coefficients on

the same sets of data. Quaestiones geographicae, 30(2),

87-93.

Huang, R., Chen, G., Yang, J., Loewen, J., 2013. Reshaping

learning frontiers of learning technology in a global

context. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Jang, S. J., Tsai, M. F., 2012. Exploring the TPACK of

Taiwanese elementary mathematics and science

teachers with respect to use of interactive whiteboards.

Computers & Education, 59(2), 327-338.

KMK, 2016. Bildung in der digitalen Welt. Strategie der

Kultusministerkonferenz. Berlin.

Lorenz, R., Endberg, M., Eickelmann, B., 2017.

Unterrichtliche Nutzung digitaler Medien durch

Lehrpersonen in der Sekundarstufe I im

Bundesländervergleich und im Trend von 2015 bis

2017. Schule digital - der Länderindikator, 84-121.

Mann, H. B., Whitney, D. R., 1947. On a test of whether

one of two random variables is stochastically larger

than the other. The annals of mathematical statistics,

50-60.

Mishra, P., Koehler, M. J., 2006. Technological

pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for

teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6),

1017-1054.

Petko, D., 2012. Teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and their

use of digital media in classrooms: Sharpening the

focus of the ‘will, skill, tool’ model and integrating

teachers’ constructivist orientations. Computers &

Education, 58(4), 1351-1359.

Redecker, C., 2017. European framework for the Digital

Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu (No.

JRC107466). Joint Research Centre (Seville site).

Reiss, K., Sälzer, C., Schiepe-Tiska, A., Klieme, E., Köller,

O., 2016. PISA 2015. Eine Studie zwischen Kontinuität

und Innovation

. Münster: Waxmann.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

548