Travelling with my SOULMATE: Participatory Design of an

mHealth Travel Companion for Older Adults

Lex van Velsen

1

, Marit Dekker-van Weering

1

, Floor Luub

2

, Astrid Kemperman

2

, Margit Ruis

3

,

Judith Urlings

4,8

, Andrea Grabher

5

, Marlene Mayr

5

, Martijn Kiers

6

, Tom Bellemans

7,8

and An Neven

8

1

eHealth Cluster, Roessingh Research and Development, Enschede, The Netherlands

2

Department of the Built Environment, Technical University of Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

3

Coöperatie Slimmer Leven 2020, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

4

Happy Aging | LifeTechValley VZW, Diepenbeek, Belgium

5

GEFAS

STEIERMARK, Graz, Austria

6

Institute of Energy, Transport and Environmental Managenent, FH Joanneum GmbH, Kapfenberg, Austria

7

ABEONAconsult BVBA, Zonhoven, Belgium

8

UHasselt - Hasselt University, Transportation Research Institute (IMOB), Diepenbeek, Belgium

judith.urlings@happyaging.be, grabher@kutz.at, mayr@generationen.at, martijn.kiers@fh-joanneum.at,

tom.bellemans@abeonaconsult.be, an.neven@uhasselt.be

Keywords: Older Adults, Mobility, Travel Aid, mHealth, Cognitive Impairments, Participatory Design.

Abstract: Mobility is an important factor in the coming about of quality of life of older adults. In this article, we discuss

the participatory design process of a mobile mobility aid for older adults (SOULMATE), which resulted in a

service model and functional specifications. We conducted 12 design sessions in Austria, Belgium, and the

Netherlands, in which we involved older adults and other stakeholders. The main values that older adults seek

to satisfy, with respect to mobility, are comfort, speed, and affordability. They also experience a myriad of

problematic situations while travelling, such as complicated ticketing systems for public transport.

Participants’ thoughts on the role of technology and their reactions towards existing applications resulted in

a service model for SOULMATE that consists of four modules: Travel planning, assistance, discovery and

training. Their functioning is detailed in a list of (non)functional requirements. As a next step, prototypes of

the SOULMATE technology will be developed and tested iteratively.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mobility is an important factor in the coming about of

quality of life of older adults. Being mobile allows

one to travel to desired people and places, leads to the

physical and psychological benefits of movement,

allows for involvement in one’s community, and

leads to a sense of self-esteem when knowing that one

is able to travel (Metz, 2000). However, due to

degeneration on the physical and cognitive front, the

mobility of older adults is often hampered over time

(Visser et al., 2005, O'Connor et al., 2010). This

manifests itself in difficulty with planning a trip and

proper navigation and orientation during a trip

(Tournier et al., 2016). For cognitively impaired older

adults, wandering becomes a serious threat (Algase et

al., 2001). In order to cope with the increasing

demand on different forms of travel by an

increasingly larger older population, new service

models and technological innovations need to be

developed (Alsnih and Hensher, 2003).

In recent years, a myriad of travel applications

was launched for mobile devices, such as

smartphones and tablets. The most well-known

application probably being Google Maps. These apps

focus on, for example, travel planning for public

transport, wayfinding while traveling, or sharing

rides. However, the functionality and visual design of

these applications do not cater towards the needs and

(cognitive and visual) disabilities of older adults

(Rassmus-Gröhn and Magnusson, 2014). As a result,

some dedicated applications for planning a trip and

wayfinding on route have been developed. Gomez

and colleagues (2015) created a travel planning and

wayfinding application for older adults with cognitive

impairments: AssisT-OUT. An evaluation showed

38

van Velsen, L., Dekker-van Weering, M., Luub, F., Kemperman, A., Ruis, M., Urlings, J., Grabher, A., Mayr, M., Kiers, M., Bellemans, T. and Neven, A.

Travelling with my SOULMATE: Participatory Design of an mHealth Travel Companion for Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0007680200380047

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2019), pages 38-47

ISBN: 978-989-758-368-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

that the application outperforms standard applications

in allowing these older adults to reach and correctly

identify their final destinations. A different

smartphone application (AssisT-In) was developed to

support people with cognitive impairments with

wayfinding indoors. The app asked users to scan QR-

codes throughout the building, so that an optimal

route could be calculated and presented. A first

evaluation showed that the designated end-users

could indeed find their way while using the

application (Torrado et al., 2016).

Other studies have taken a more fundamental

approach and looked at the conditions that

wayfinding technology for older adults will need to

fulfil, or values it should satisfy. Sorri, Leinonen and

Ervasti (2011) found that older adults with some form

of dementia have difficulties with straying from

predefined routes, finding the right door, and specific

attractions like people or pretty views. They also

found that supporting navigation by showing

landmarks on a handheld device did not turn out to be

as effective as providing precise and correctly timed

advice (e.g., clearly stating “turn left” or “go straight

ahead”). Boerema and colleagues (2017) studied the

topic on a more abstract level and identified the

values that older adults have when it comes to using

mobility aids. Facilitating social interaction, fostering

independence, and relaxation were the most

important values in this.

However, in order to develop wayfinding

technology that can aid older adults (with or without

cognitive impairments) and that can collect the data

that is necessary for identifying cognitive decline,

design processes should highly involve prospective

end-users (Pulido Herrera, 2017). Apart from these

findings, the number of applications for planning a

trip and wayfinding on route for elderly and the

amount of evaluations that are published about these

applications are limited (Bosch and Gharaveis, 2017).

In this article, we discuss the participatory design

process of a mobile mobility aid for older adults,

taking into account their diversity in terms of mobility

profile, country of origin, and living environment.

Section 2 explains the Soulmate project which forms

the context of the development process. In Section 3,

we elaborate on the participatory design methods we

used to develop (1) a service model, and (2)

functional specifications. Results are presented in

Section 4, and discussed in Section 5.

2 THE SOULMATE PROJECT

In the SOULMATE (Secure Old people’s Ultimate

Lifestyle Mobility by offering Augmented reality

Training Experiences) project, a consortium of

research organizations, end-user organizations and

SME’s collaborate to develop a personalised,

customizable smartphone-based mobility solution for

older adults (Neven et al., 2018). The goal of the

Soulmate project is to develop a digital solution that

caters for the different mobility needs that older

adults have fitting their physical and cognitive

abilities. It should evolve alongside the end-user’s life

stages and needs (e.g., starting out as a healthy older

adult that just stopped working, to a senior with some

problems walking which impairs self-confidence, to

an older adult with mild or moderate cognitive

impairments). The SME’s involved bring in a set of

mobility solutions for older adults with a wide range

of mobility-related needs: Route training by means of

a virtual training environment (Memoride), passive

monitoring of trips to enable geofencing and travel

coaching by an informal caregiver from a distance

(Viamigo), indoor and outdoor route planning and

assistance during a trip (Ways4all), and finally, a

panic button for emergency assistance while

travelling.

3 METHOD

During the design phase of the SOULMATE

technology, a participatory approach was used, in

which prospective end-users and stakeholders

collaborated with researchers. In total, 12 design

sessions were held in two rounds. In the first round,

sessions focused on making an inventory of problems

that older adults encounter while travelling, and on

creating a service model for the Soulmate technology.

Sessions in the second round aimed at eliciting

functional and non-functional requirements, and at

assessing end-user acceptance of the individual

Soulmate technologies that the participating SME’s

brought in.

3.1 Participants

Participants of the design sessions needed to be at

least 65 years old, willing to provide informed

consent and able to discuss the topics on the table.

Since older adults of 65 and over is a very diverse

group, we applied a stratified recruitment strategy.

Travelling with my SOULMATE: Participatory Design of an mHealth Travel Companion for Older Adults

39

See Table 1 for the different groups that were

recruited.

Table 1: Participant groups in the design sessions.

Country Group 1 Group 2

Austria Native inhabitants Immigrants

Belgium Mobile Mobility impaired

Netherlands Urban Rural

For each group, a design session was held in the first

round and in the second round, which makes for a

total of 12 design sessions. Mobile participants were

defined as older adults that could travel without

assistance; participants with a mobility impairment

were recruited from an assisted living facility.

Besides older adults, representatives of secondary

end-users (e.g., family members or informal

caregivers) were also invited, as well as

representatives of tertiary end-users like informal

caregivers. These ‘additional’ participants were

treated like the primary end-users and asked to

collaborate in developing technology.

3.2 Round 1

The design sessions in the first round (which focused

on making an inventory of problems that older adults

encounter while travelling, and on creating a service

model for the Soulmate technology) consisted of the

following parts:

1. Introduction of the session moderators and goals

2. Introduction of the participants. They were asked

to state their name, and some basic demographics.

3. Value elicitation. By using the fictitious story of

Martin (who explained what he valued while

travelling), we questioned the participants about

their values and asked them to rate these values on

importance, by placing them on a radar (less

important on the outside, more important near the

center).

4. Inventory of troublesome situations. We provided

the participants with two typical journeys (going

to the grocery store, visiting family) and created a

visual overview of these travels. Different travel

modalities were used in these overviews (walking,

cycling, public transport, car). We asked the

participant to mark where they normally have

problems.

5. Potential role of technology. In pairs, participants

received the same overviews as in part 4, but were

asked to put stickers of different technologies

(e.g., wayfinding app, panic button) on it at the

places where they thought this technology would

be beneficial. They could also think of

technologies, besides the predefined stickers and

write these down on the overviews. Then, the

pairs were asked to present their work in plenary,

and the group discussed the results.

All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed,

except for the Austrian ones, which were transcribed

while being conducted. Pictures were made of the

products that the participants made. Parts 2, 3 and 4

were closely scrutinized and similar answers were

counted. Part 5 served as input for the service model

design. Here, we combined the needs and wishes that

the participants expressed and the technical solutions

that could be, realistically, developed, and the

economic viability of the solution (as viewed by the

participating SMEs).

3.3 Round 2

The design sessions in round 2 (which focused on

eliciting functional and non-functional requirements,

and on assessing end-user acceptance of the

individual Soulmate technologies) consisted of the

following parts:

1. Introduction of the session moderators and goals.

2. Introduction of the participants. Similar to the

introduction round of round 1.

3. Co-design activity. In pairs, participants created

their own mobile travelling companion. More

specifically, they were given handouts of blank

mobile phones, colouring kits, ballpoints, etc. to

create an interface (or set of interfaces) for three

tasks: Preparing a trip, dealing with changes

during a trip (e.g., a delay while travelling by

train), and calling for help during a trip. These

tasks were chosen as they turned out to be

perceived as troublesome by the target population

during round 1. Since this was a creative, and

perhaps difficult task, session moderators helped

the participants continuously (e.g., by asking

questions that could guide design: “What kind of

information do you need here?”, “Which button

would you like to see here?”).

4. Plenary discussions of co-designs. All pairs

showed their designs to the group and explained

their design decisions. Other participants were

encouraged to provide comments or suggest

improvements.

5. Acceptance of Soulmate technology. The

different technologies that are provided by the

Soulmate SME’s were demonstrated. Then,

participants were asked about their first reaction

and whether they thought a technology was useful

or not.

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

40

Again, all sessions were audio-recorded and

transcribed, or transcribed on spot (Austria); pictures

were made of the co-designs. Demographics were

counted. Results of the co-design activity (drawings

and discussion) were scrutinized for relevant

functionalities or interface/interaction attributes and

then translated into a requirement. Prevalence was not

an important issue here, as an idea provided by a

single participant could be just as relevant as a

functionality desired by the far majority. Each

requirement was categorized using FICS

categorization (Functions & events, Interaction &

navigation, Content & structure, Style & aesthetics)

and prioritized via the MoSCoW method (Must have,

Could have, Should have, Won’t have). Furthermore,

the participating SME’s indicated whether each

requirement could be incorporated in the Minimum

Viable Product (MVP), a version 2.0, only in a later

version, or not at all. This way, we could grasp the

technical feasibility of each request.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Round 1

In total, 42 older adults participated in round 1, with

a mean age of 72 years. In the Netherlands, four

persons that lived in a rural area took part, while six

persons that lived in an urban area were present. In

Belgium, 14 mobile persons frequented a session,

followed by four less mobile older adults. In Austria,

finally, six native Austrians were present in a session,

while eight immigrants visited the next session.

Besides these end-users, stakeholders also

participated in the co-design meetings. In Belgium,

one psychologist/gerontologist and one mobility

volunteer were present. In Austria, two

representatives from the participating SOULMATE

SME’s participated in both sessions. Sessions lasted

about two hours.

4.1.1 Values

The values that were mentioned at least five times in

total by the different participants in the different

sessions are listed in Table 2. The table shows that

comfort, speed, affordability, safety, and

independence were mentioned most.

4.1.2 Troublesome Situations

During the workshops the participants were shown

(or asked to create) two trips and asked to indicate

problematic situations that could occur during such

trips. Per mode of transportation, the following

situations were mentioned.

Walking. Not many problems were experienced

while walking. Limited physical fitness was

mentioned in combination with the possible travel

distance and walking uphill.

Table 2: Travel-related values mentioned by participants (at least five times).

Value The Netherlands Belgium Austria Total

Urban Rural Mobile Less mobile Native Migrant

Comfort 3 3 3 1 4 2 16

Speed 3 2 6 1 1 1 14

Affordability 3 7 2 1 1 14

Safety 6 1 4 1 12

Independence 1 4 3 2 1 1 12

Social contact 3 1 3 2 1 1 11

Having information while

travelling

2 3 1 1 2 2 11

Having information

before travelling

1 1 1 2 2 2 9

Reliability, punctuality 5 1 1 2 9

Distance to public

transport

2 2 2 1 1 8

Transportation of luggage 1 3 2 1 1 8

Little physical activity 2 1 3 1 7

Physical activity 3 1 1 1 6

Avoid traffic congestions 1 4 1 6

Not being rushed 3 2 5

Travelling with my SOULMATE: Participatory Design of an mHealth Travel Companion for Older Adults

41

Biking. The participants felt vulnerable and

sometimes unsafe while riding a bicycle. They felt

threatened by cars and other cyclists who do not pay

enough attention. Some persons told of an accident,

which made them avoid cycling. Safety was only

mentioned by participants living in an urban

environment in the Netherlands and by both types of

participants in Austria, not in Belgium. In the

Netherlands an unsafe feeling was also caused by the

inconsistency in priority rules for Dutch roundabouts.

Driving a Car. Traffic congestions were considered

an annoyance while travelling by car. Participants

experienced stress while finding a parking spot or

finding directions on busy roads. When asked about

the possibility of being picked up or dropped off by a

friend or family member, several participants

indicated that they try to avoid this because they do

not want to burden other people.

Public Transport. All participants thought that the

public transport system, and the ticketing system in

particular, was confusing. To them, it was unclear

where or how tickets can be purchased and what the

difference between the types of tickets and pricing is.

Trains and Train Stations. In train stations, the fast

and inaudible information and lack of, or unclear,

signage leads to confusion. In the Netherlands,

problems were experienced with the accessibility of

the stations and platforms. In Belgium and the

Netherlands, the lack of information in general when

travelling by train was often mentioned. Situations

where a trip deviates from the normal, or planned,

itinerary (change of route or platform) were

considered stressful and led to fear of taking the

wrong train. The short transfer times and limited

boarding time gives a feeling of being rushed. Finally,

the crowdedness, possible lack of a seat and anti-

social behaviour of other passengers were also

reasons for concern.

Busses and Bus Stops. The lack of up to date travel

information at bus stops and unreliable schedules

were often mentioned in all countries. The lack of

seating and high entry of the bus were experienced as

troublesome, due to a lack of balance and physical

limitations, caused by older age. The distance to and

from the bus stop was mentioned as being too long,

depending on the preferences and level of physical

fitness of the participant.

4.1.3 Potential Role of Technology

The participants introduced and discussed several

general functionalities of technology that could

support them while travelling.

Route Training. Some participants stated that when

travelling to unfamiliar places, technology like route

training might be helpful to recognize landmarks.

They could imagine checking exits at train stations

and other important places before embarking on a

trip. However, most of the participants thought that

such functionalities would not be very useful, as they

would forget what they have seen while travelling.

Participants liked to view pretty views (like

buildings) or routes on the map, but could not imagine

training a route themselves.

Travel Planning. Travel planning was already used

by a lot of participants (e.g., Google maps, Quando).

It helps to know how long a trip will take, what they

will encounter en route, and what type of transport to

take. People wanted to know how much time they

would have for transferring between trains/ buses,

and to create a forecast of potential difficulties

(roadworks, delays, short transit times), so that they

could be prepared.

Real Time Travel Updates. Participants liked to

receive information about the remaining time a trip

would take and unforeseen events. Technology

should provide practical advice on how to deal with

such events. Besides, participants would like to

receive information about the history of the

destination and its local events. Finally, they would

like to know where the nearest restroom is at all times.

Route Security. Participants indicated that the older

one becomes, the more important it is to have other

people know where you are, as something might

happen. Participants saw the potential of such

services for other older people, but not for them.

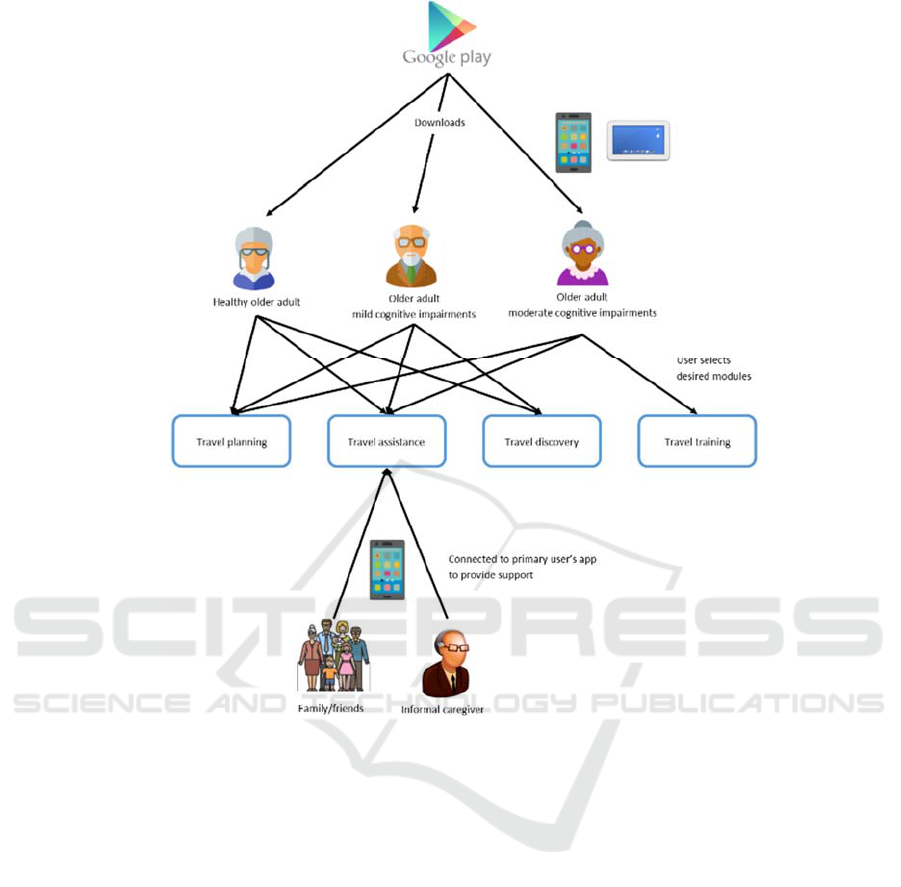

Based on the inventory of troublesome situations

and the participants’ view on the potential of

technology, we created a service model for the

Soulmate service (see Figure 1). This service model

also took into account which technologies the

participating SME’s thought ready and interesting to

the market. The main premise is that the technology

is divided in four modules with a similar look and

feel. The reason for this is that the participants did not

express an overall wish for a set of services, but

linked these towards the physical and cognitive

capabilities of the end user (divided into healthy older

adults, mild cognitive impairments, moderate

cognitive impairments). Each module reflects a

product brought in by an SME, participating in

SOULMATE. The travel exploration and training

modules are the exception here. These modules are

basically the same, but are marketed differently.

Healthy older adults did not feel they need to train

their travelling, but were fine with exploring their

destinations. Each older adult can select the modules

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

42

Figure 1: SOULMATE service model.

that s/he would like to use. Whenever the Travel

assistance module is selected, secondary end-users

(friends, family, care professionals) become relevant

and can be linked to the individual end user, so that

they can assist them during their travels.

4.2 Round 2

In total, 40 older adults took part in round 2, with a

mean age of 71 years. This time, in the Netherlands,

five persons that lived in a rural area participated and

another five persons that lived in an urban area were

present. In Belgium, 13 mobile older adults

participated and six less mobile persons took part. In

Austria, finally, five native Austrians participated, as

well as five immigrants. Next to these potential end-

users, a coordinator of an elderly service center and a

mobility volunteer participated in Belgium. In

Austria, six representatives from one of the

participating SOULMATE SME’s were present. The

sessions lasted about two hours.

4.2.1 Requirements

The participants made a lot of co-designs for the

SOULMATE app to support them in the tasks of

preparing a trip, dealing with changes during a trip,

and calling for help during a trip. Figure 2, 3 and 4

provide examples of such designs. In Figure 2, the

participants created functionality for travel planning.

They wished to insert a destination address, select

their travel modality, and specified what they would

like to see as output (travel duration, distance,

obstacles, etc.). In Figure 3, participants specified

what they would like to receive from the mobile app

during a trip, like a map where the restroom and the

current location of the end-user is specified. Figure 4,

finally, shows that this pair of participants liked to

have a simple alarm function in which a list of names

was available, and that (video)calling a specific

person should be able with one click.

Travelling with my SOULMATE: Participatory Design of an mHealth Travel Companion for Older Adults

43

Figure 2: Co-design of travel planning functionality.

Based on the co-designs and the participants’

presentation of their work, 58 requirements were

drafted. These 58 requirements were prioritized,

based upon the urgency with which the participants

mentioned a wish. Subsequently, the design team

discussed with the participating SME’s which

requirements were feasible for the MVP.

In relation to travel planning, the service must:

allow end-users to choose a location on a map as

the place of destination;

clearly show transfer times when travelling with

public transport;

allow end-users to select different transport

modes when planning a trip (e.g., bike, car, public

transport);

make very clear what the start and the end of a trip

is;

allow the end-user to define a route with multiple

stops;

provide a clear overview of the planned trip.

Wishes that were estimated to be too complicated

for inclusion in the MVP were transferred to version

2.0. These include showing the altitude of a route

(relevant in Austria), providing a checklist of things

that people need to bring on a trip, or indicating when

a trip is made in the dark or not (as the participants

indicated they want to prevent this).

With regard to travel assistance, the service must:

only display real-time travel updates when

travelling by public transport, car, or bike

show alternative routes in case of a calamity

(delay, traffic jam, road closure)

notify an end-user when going the wrong way

Figure 3: Co-design of travel assistance functionality.

Figure 4: Co-design of alarm functionality.

allow an end-user to store where they parked the

car or bike, or where they got off the bus

provide information about the accessibility of the

transport options and destination

not overload the end-user with information

provide a map of stations and airports and their

places of interest (escalators, exits, etc.)

share personal information with a person that is

being called in case of an emergency (including

location)

provide a panic button that can be activated by one

push

allow the end-user to choose between text and

speech feedback

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

44

provide the option to establish a video-chat in case

of an emergency.

Wishes that were transferred to version 2.0

include the option to provide a summary of a trip

when reaching the destination (e.g., kilometres

travelled, height covered), continuously sharing the

current location of the end-user with a predefined

friend or family member, or indicating when a person

needs to get off a bus, tram, or train.

With respect to travel discovery and training, the

co-designs did not generate any input for the

formulation of requirements. The participants thought

that this functionality was not of relevance for them.

As a result, the design team decided to integrate these

modules as a technology push. In general, the service

must have a clear and easy privacy statement, must be

battery-friendly, and must clearly show the current

location of the end-user on a map.

4.2.2 Gauging Acceptance

Finally, we gave demonstrations of the current

versions of the to-be integrated SOULMATE

technologies (i.e., the versions that were available

before the design sessions), and questioned the

participants about their acceptance.

Route Monitoring. This service (Viamigo,

www.viamigo.be) offers real-time monitoring of trips

by a remote coach. In short, it is determined whether

a person strays too far from a predefined route, in

which case the coach is alerted. Reaction to this

solution were mixed. Some participants thought that

if you need such a solution, you should probably not

travel at all. Others said that it would give comfort to

the family of the user, and might motivate people to

go out. Finally, participants were worried that

learning to use such technology might be difficult in

case you need it, due to cognitive impairments.

Route Training. This service (Memoride,

www.memoride.eu) offers people the possibility to

train a route on home trainers or while sitting, by

displaying a route (created from Google street view

images) on a large screen or tablet. Most of the

participants saw this solution as a ‘fun thing’, but not

for real training purposes. They did see the

possibilities for people who are not able to travel

anymore. For them, it could be a fun and health

exercise device. Most participants did not see the

value of this service for training a route. They thought

that the fun of travelling is in the unknown; to see

things for the first time. Even when they would train

the route, they said, they would probably not

remember it when making the actual trip. Finally,

they indicated that if they were in a situation where

they had to train a route, they would probably not

travel at all, as they would feel too insecure.

En Route Assistance. This demo showed the

Ways4all application (ways4all.at), which aims to

support active navigation. It provides indoor and

outdoor navigation, provides route information

(obstacles, elevators, restrooms) and takes into

account personal preferences and characteristics

while navigating (providing the shortest route, or one

without stairs). It can signal help (e.g., to a bus driver

when a person needs to be aided to disembark), and it

also provides a help button, which activates a

connection with a preselected person and conveys the

traveler’s location and planned route. Participants

responded positively towards this solution. Especially

in Austria, participants liked to communicate with

public transport personnel, and would also use the

video help function.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this article, we have discussed the co-design

process of a mobile travel solution for older adults,

either with or without cognitive and/or physical

impairments. This process resulted in a service model

and a set of (non)functional requirements. Together,

they will be the foundation of the SOULMATE

service.

The SOULMATE service model offers older

adults the possibility to select one or multiple travel

modules, focused on travel planning, travel

assistance, and travel discovery/training. The targeted

end-users (and purchasers) of the service are older

adults of 65 years and above. Such a broad target

group was chosen to ease the transition from healthy,

active senior towards a senior with physical and/or

cognitive impairments. An older adult can choose to

use the travel planning module only when in good

shape, but can choose to extend the SOULMATE

service later on with a travel assistance module (and

panic button), when physical and/or cognitive

degeneration leads to a situation in which the traveler

does not feel as secure as s/he used to feel.

Participants in the design sessions indicated that they

thought many options were ‘not for them, but for

people that are actually old’. Previous research has

acknowledged that older adults cannot imagine using

or purchasing an assistive technology when there is

no direct personal need (Peek et al., 2017). And when

there is a need, issues like privacy, costs, stigma, and

factors related to usability and a need of training can

hinder uptake (Yusif et al., 2016). By offering

SOULMATE as a ‘normal’ travel app to older adults

Travelling with my SOULMATE: Participatory Design of an mHealth Travel Companion for Older Adults

45

first, and to extend the service when the need arises,

the barriers of stigma, usability and need for training

can be tackled.

The requirements which were derived from the

design sessions specify how a mobile travel service

for older adults (with or without cognitive

impairments) needs to have specific features to cater

for these end-users. Being able to notify a bus driver

that a person with mobility needs has to disembark,

storing the location where one parked a car, or

information about the nearest restroom are examples

of functionalities that make such a technology

interesting for older adults, and that allow them to

remain mobile when facing the consequences of

becoming older.

The SOULMATE requirements elicitation and

design approach were highly participatory. The use of

these design methods is slowly becoming common

practice when creating innovations for older adults

(e.g., van Velsen et al., 2015, Šabanović et al., 2015).

We found that during our sessions, older adults were

enthusiastic to collaborate. Unlike other projects, we

decided not to use the co-designs that the participants

made as a blueprint for the SOULMATE design.

Instead, we elicited the rationale behind their design

decisions and used these to draft (non)functional

requirements. Then, and in close collaboration with

the participating SME’s, we decided which

functionality to implement or not, also taking account

what is technically feasible and makes sense from a

business perspective.

5.1 Limitations

Like any study, this work has some limitations. First,

the sample of older adults that participated in the

design sessions had a slight overrepresentation of

healthy older adults. As a result, the participants’

views on assistive technology for people with

cognitive decline may be too negative. Or, they might

not have thought they might need or use the

technology at the moment, thereby giving a

somewhat biased image of the participants’ intention

to use the technology. Second, we did not have the

opportunity to conduct a full stakeholder analysis

(including mapping, determining salience). As a

result, we opted for including stakeholders that were

willing and able to participate.

5.2 Future Work

The next step in the SOULMATE project will be to

develop prototypical versions of the technology.

These prototypes will enter a series of iterations in

which technical reliability, usability, and acceptance

will be tested and improved. Then, the MVP will be

evaluated in a real-life study with a focus on mobility,

quality of life and informal caregiver burden. In the

meantime, the participating SME’s will work out a

value proposition, business model and exploitation

strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article is based on the research work conducted

in the SOULMATE project (AAL grant agreement

#2013-6-091); www.soulmate-project.eu. The

SOULMATE project is co-funded by the AAL

Programme of the European Union and by the

funding authorities Agentschap Innoveren en

Ondernemen (Flanders, Belgium), Austrian Ministry

for Transport, Innovation and Technology (Austria)

and ZonMw, the Dutch Organization for Health

Research & Development (The Netherlands).

REFERENCES

Algase, D. L., Beattie, E. R. A. & Therrien, B. 2001. Impact

of Cognitive Impairment on Wandering Behavior.

Western Journal of Nursing Research, 23, 283-295.

Alsnih, R. & Hensher, D. A. 2003. The mobility and

accessibility expectations of seniors in an aging

population. Transportation Research Part A: Policy

and Practice, 37, 903-916.

Boerema, S. T., Van Velsen, L., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.

M. R. & Hermens, H. J. 2017. Value-based design for

the elderly: An application in the field of mobility aids.

Assistive Technology, 29, 76-84.

Bosch, S. J. & Gharaveis, A. 2017. Flying solo: A review

of the literature on wayfinding for older adults

experiencing visual or cognitive decline. Applied

Ergonomics, 58, 327-333.

Gomez, J., Montoro, G., Torrado, J. C. & Plaza, A. 2015.

An Adapted Wayfinding System for Pedestrians with

Cognitive Disabilities. Mobile Information Systems,

2015, 11.

Metz, D. H. 2000. Mobility of older people and their quality

of life. Transport Policy, 7, 149-152.

Neven, A., Bellemans, T., Kemperman, A., Van Den Berg,

P., Kiers, M., Van Velsen, L., Urlings, J., Janssens, D.

& Vanrompay, Y. 2018. SOULMATE - Secure Old

people’s Ultimate Lifestyle Mobility by offering

Augmented reality Training Experiences. The 8th

International Conference on Current and Future

Trends of Information and Communication

Technologies in Healthcare. Leuven, Belgium:

Elsevier.

O'connor, M. L., Edwards, J. D., Wadley, V. G. & Crowe,

M. 2010. Changes in Mobility Among Older Adults

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

46

with Psychometrically Defined Mild Cognitive

Impairment. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B,

65B, 306-316.

Peek, S. T. M., Luijkx, K. G., Vrijhoef, H. J. M., Nieboer,

M. E., Aarts, S., Van Der Voort, C. S., Rijnaard, M. D.

& Wouters, E. J. M. 2017. Origins and consequences of

technology acquirement by independent-living seniors:

towards an integrative model. BMC Geriatrics, 17, 189.

Pulido Herrera, E. 2017. Location-based technologies for

supporting elderly pedestrian in “getting lost” events.

Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology,

12, 315-323.

Rassmus-Gröhn, K. & Magnusson, C. 2014. Finding the

way home: supporting wayfinding for older users with

memory problems. Proceedings of the 8th Nordic

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Fun,

Fast, Foundational. Helsinki, Finland: ACM.

Šabanović, S., Chang, W.-L., Bennett, C. C., Piatt, J. A. &

Hakken, D. 2015. A Robot of My Own: Participatory

Design of Socially Assistive Robots for Independently

Living Older Adults Diagnosed with Depression.

International Conference on Human Aspects of IT for

the Aged Population. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Springer

International Publishing.

Sorri, L., Leinonen, E. & Ervasti, M. Wayfinding aid for the

elderly with memory disturbances. European

Conference on Information Systems, June 9-11 2011

Helsinki, Finland. AIS Electronic Library, paper 137.

Torrado, J. C., Montoro, G. & Gomez, J. 2016. Easing the

integration: A feasible indoor wayfinding system for

cognitive impaired people. Pervasive and Mobile

Computing, 31, 137-146.

Tournier, I., Dommes, A. & Cavallo, V. 2016. Review of

safety and mobility issues among older pedestrians.

Accident Analysis & Prevention, 91, 24-35.

Van Velsen, L., Illario, M., Jansen-Kosterink, S., Crola, C.,

Di Somma, C., Colao, A. & Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.

2015. A Community-Based, Technology-Supported

Health Service for Detecting and Preventing Frailty

among Older Adults: A Participatory Design

Development Process. Journal of Aging Research,

2015, article no. 216084.

Visser, M., Goodpaster, B. H., Kritchevsky, S. B.,

Newman, A. B., Nevitt, M., Rubin, S. M., Simonsick,

E. M. & Harris, T. B. 2005. Muscle Mass, Muscle

Strength, and Muscle Fat Infiltration as Predictors of

Incident Mobility Limitations in Well-Functioning

Older Persons. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A,

60, 324-333.

Yusif, S., Soar, J. & Hafeez-Baig, A. 2016. Older people,

assistive technologies, and the barriers to adoption: A

systematic review. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 94

, 112-116.

Travelling with my SOULMATE: Participatory Design of an mHealth Travel Companion for Older Adults

47