Minimizing the Number of Dropouts in University Pedagogy Online

Courses

Samuli Laato, Emilia Lipponen, Heidi Salmento, Henna Vilppu and Mari Murtonen

Department of Education, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

Keywords: Online Education, Distance Learning, Engagement, Retention, University Pedagogy, Staff Development.

Abstract: Students’ engagement and retention in online courses have been found to be in general significantly lower

than in contact teaching. Multiple reasons for this exist, but improving student retention is ubiquitously seen

as a beneficial improvement. We take a look at student engagement in online courses aimed specifically for

university teachers and doctoral students, and use a mixed methods approach to obtain a holistic understanding

of student engagement in our domain. We analyse quantitative data from two cases (n=346 and n=271)

collected from students of three university pedagogy online modules over the course of years 2016-2017. We

identify key moments in our modules where students drop out and, for example, differences in dropout rates

between various demographics (i.e. faculty and whether the student is a university staff member or not). The

main moment where students drop out is found to be in the very beginning of the courses, and the introduction

of a pre- and post-test to the courses improved retention. This study suggests that when all other factors

affecting student engagement are in order, additional focus should be paid to the very beginning of the course

and get as many students to do the first couple tasks as possible in order to reduce the dropout rate.

1 INTRODUCTION

Online courses have become notorious for their high

dropout rates in comparison to contact teaching (Lee

and Choi, 2011; Murhpy and Stewart, 2017). A 2014

study reports most Massively Open Online Courses

(MOOC’s) have a dropout rate higher than 87%

(Onah et al., 2014) or even 90% (Gütl et al., 2014).

The situation is arguably better with Small Private

Online Courses (SPOC’s), but as there is too much

variance in the way SPOC’s are organised, it is

impossible to make an accurate general comparison

between the two. This can be seen in the statistics, as

research in online course engagement and student

retention heavily favors MOOC’s over SPOC’s. For

example, a search on Google Scholar on articles

published in 2017-2018 with the term “SPOC dropout

rates” yields 152 search results, whereas a search on

the same years with “MOOC dropout rates” yields

1430 results. Both types of online courses are still

present in recently published papers of all levels.

Multiple reasons exist why SPOC organisers want

to enhance students’ engagement in their courses. Not

only do more engaged student learn better (Kuh,

2003), but engagement also reduces course dropout

rates and increases retention. Due to the causal

relationship between student’s retention and engagem-

ent, dropout rate can be seen as an indicator of general

student motivation during online courses. Therefore it

is feasible to presume that a MOOC or a SPOC with a

high dropout rate is also not the most engaging and

motivating course for those students who pass it.

In this study we focus on engagement in online

courses, with emphasis on courses aimed for

university employers, researchers and doctoral

students. As a case study we will use data collected

from three SPOC style university pedagogical online

modules organised in the University of Turku

between 2016-2017 (Laato et al., 2018). In our

courses we observed a dropout rate of 55% of

students over 346 course enrollments. We then

introduced a pre and post -test setup in our modules

in order to measure students’ learning, and

unexpectedly recorded an increase in student

retention with the dropout rate falling as low as 34%

with 271 enrollments in autumn 2017. This

observation prompted us to form the hypothesis that

the time consuming “first task” as we named our

pretest, actually increases student retention despite it

creating additional workload for the students.

However, the situation is quite complex and

multilayered. Naturally multiple factors affect student

retention, and a single statistic of the course dropout

Laato, S., Lipponen, E., Salmento, H., Vilppu, H. and Murtonen, M.

Minimizing the Number of Dropouts in University Pedagogy Online Courses.

DOI: 10.5220/0007686005870596

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 587-596

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

587

rates was insufficient in creating an understanding of

the overall student engagement in our case courses.

In order to gain a holistic understanding of student

retention in university pedagogy online courses, using

our case study and previous studies as sources, we

utilize a mixed methods approach and propose the

following research questions to be answered in this

study:

1. How well do our online courses take into account

the factors influencing student engagement and

retention that have been identified in previous

studies?

2. When dividing our online module into small

segments, in which parts do most students drop

out?

3. What then makes the specific segments such

which cause students to yield their participation in

our courses?

4. Are there any statistically significant differences

in student retention between:

a) Faculties

b) Doctoral students and University Staff

c) Student age

d) Our three case study courses.

First, we go through prominent previous studies in the

field, and identify the major factors affecting student

retention that the studies bring forth. Second, we

compare our course and platform design to these

factors, in order to see if and how we have taken them

into account. Thirdly, we analyse quantitative data

collected from our case courses between the years

2016-2017 to find answers to the rest of the research

questions. We finalize this study with a discussion on

the current situation of engagement and retention in

university pedagogy online courses and propose ideas

for future studies.

2 BACKGROUND

Online learning provides flexible studying

possibilities that are not time or place dependent.

Thus, it can be regarded suitable for educating adults

that are already in working life. Online learning is

also considered a cost-effective way of organizing

education, as the only fixed costs for holding an

online course after it is finished are maintenance fees.

A popular criticism on online learning has been that

it is unsocial and lacks the social presence of contact

teaching, but for example Costley and Lange (2018)

show that quality collaborative learning situations can

occur online. Already in 2004 Zhang et al. stated that

e-learning can supplement classroom learning, and at

times be more effective than traditional teaching

methods. Since then, online learning studies have

become numerous. The research on online learning

used to focus on young degree students whereas adult

learners received less attention (Ke and Xie 2009)

although the amount of adult students in online

courses was higher (Kahu et al., 2013). However,

recently a broad range of studies on adult learning

have emerged, for example (Broadbent and Pool

2015; Deming et al., 2015; Hoffman, 2018).

In the early retention studies the focus was on

degree studies (Murphy and Stewart 2017, 4). Some

recent studies have focused on long-term engagement

in studies with the timeframe varying from one

semester to whole degree programme (Yang et al.,

2017; Yoo and Huang 2013). Course-specific

engagement has been examined in past few years

mostly in MOOC courses. The length of these courses

vary between 5 to 12 weeks and they are usually open

for everyone without prerequisites (Henderikx et al.,

2017). Short courses and training have received less

attention. MOOC research has, however, produced

great amount of information that is applicable to

online learning generally.

2.1 Engagement in Online Learning

Engagement can be divided into three types:

behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement

(Henrie et al., 2015). Archambault (2009) carried two

studies using the three above mentioned indices:

behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement in

order to gain insight on which of these three might

have a causal relationship with students’ high school

dropout rates. The findings were, that at least in the

high school context, only the behavioural engagement

affects students’ retention. More specifically, rule

compliance, interest in school and willingness to

learn were identified as factors that indicate an

increased risk for dropping out. Problems with

emotional and cognitive engagement did not seem to

have an effect, however, this cannot be

straightforwardly transferred to the context of online

courses for adult students.

Student’s possibilities to control his/her studies

are also connected to engagement. Control can be

divided into instruction related control and control of

schedule (Karim and Behrend 2015). The more

students can influence teaching (pace, order, content)

the more they have to focus on off-task aspects and

self-regulation, which might be problematic from

engagement and learning perspective. In contrast,

control of schedule can promote engagement.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

588

2.2 Adult Learners Engagement in

Online Courses

The knowledge obtained from retention and

engagement studies with younger demographics

might not straightforwardly transfer to adult learners,

therefore it is important to take a look at adult learners

in online courses specifically (Ke and Xie 2009).

Some studies show that for adult learners the

relevance of studies for individual and professional

needs, possibility to acquire skills and satisfaction

with the courses and learning results are central in

promoting continuing studies (Yang et al., 2017).

Additionally, adult learners can utilize their

professional experience in their studies and

respectively apply their learning in their work (Kahu

et al., 2013). In recent MOOC research the focus has

been on motivating factors of the courses (Watted and

Barak, 2018). Watted and Barak (2018) compared the

perceptions of higher education students and other

course participants in a STEM MOOC regarding the

benefits of MOOC course. They discovered that for

students with higher education background studying

is based on personal and education related reasons,

whereas other participants, e.g. academic researchers’

motives were work and career related in addition to

personal reasons. Studies on SPOC courses have

identified a direct correlation between engagement

and performance (Liu et al., 2018).

For adult learners environmental or external

factors, such as family or organizational support or

lack thereof, are significant reasons for quitting

online learning (Park and Choi, 2009). According to

Vayre and Vonthron (2017), of different types of

social support only teacher’s support has a crucial

role in online learners’ engagement in studies.

Nevertheless, they also stress the importance of a

sense of community and presence for engagement.

The sense of community promotes the development

of academic self-efficacy (ibid.). Creating sense of

social presence in online settings depends both on the

interaction between instructor and students and

between students (Shelton et al., 2017). Interaction

with peers does not necessarily exist in an online

course, even though it has been identified as a major

component in improving student retention (Shelton,

et al., 2017; Costley and Lange 2018; Hew et al.,

2016).

2.3 Dropout Rates in Online Courses

High dropout rates in online courses have been paired

with a low level of engagement (Willging, 2009).

SPOC courses generally record significantly lower

dropout rates in comparison (Kaplan and Haenlein,

2016), but the results are hard to objectively

generalize as there is a large variance in the way

SPOC’s are organized. Some, for example, contain

elements of blended learning (Martínez-Muñoz and

Pulido, 2015) and the dropout rate can also be

influenced by SPOC’s often being compulsory to

educational degrees whereas MOOC’s are not. The

dropout rate in MOOC’s has been recorded to be so

staggeringly high, that it has sparked a numerous

amount of research from various angles trying to

discover the reasons behind students dropping out.

Onah et al., (2014) found 8 reasons in their study of

why people drop out of MOOC courses:

1. No intention to complete.

2. Lack of time.

3. Course difficulty and lack of support.

4. Lack of digital skills or learning skills.

5. Bad experiences.

6. Expectations

7. Starting late

8. Peer review

These reasons have all been explored in further detail.

For example, Stracke (2017) argues that the high

dropout rates in MOOC’s are a natural phenomenon

that we should not attempt to fix. Because enrolling

to online courses gives students access to all the study

materials and because the barriers for entry are so

low, many students join MOOC’s with no real

intention to complete them, or to take a look if the

course seems good enough for them to complete at a

later time. This, however, is not the case in our case

study, as the course material in our case study is open

for everyone at all times regardless of enrolment.

In addition to the 8 reasons listed by Onah et al.

(2014), at least the demographic can have an impact

to student retention and motivation. Cochran et al.,

(2014) analyse the effect of student characteristics on

retention and form a model predicting the probability

of a student withdrawing from an online course based

on their prior study record. Hew et al., (2016) takes a

look at why some MOOC courses were rated better

by students than others, and found out that if the

course is built so that most learning is problem-

centred, students have access to a passionate

instructor, the course utilizes active learning methods

and peer interaction and provides helpful course

resources, then it is much more likely to be found

engaging by students. There is much additional

evidence that certain types of tasks and a certain kind

of a course design is effective than the alternatives in

online courses in general (Fournier, 2015). Fournier

Minimizing the Number of Dropouts in University Pedagogy Online Courses

589

(2015) highlights participant focused and learner

driven processes as the most important factor in

making a MOOC engaging and motivating. These

findings and the motivation to create better online

courses has led to the development of strategies and

frameworks which assist in developing and

implementing an online course in a way that is more

likely to result in high levels of engagement in course

participants.

Fidalgo-Blanco et al., (2016) explored the role of

the course participants profile and the pedagogical

model in attrition from MOOC courses. They

developed a model which combines MOOCs based

on traditional online learning platforms (xMOOC)

and connectivist MOOCs (xMOOC) based on

collaboration and utilization of social media

applications. Their findings were that the model had

stronger impact on course completion rate than

factors related to the learning platform, participants

profile or course theme. In addition, student centred

teaching and collaborative learning were found to

have a positive effect on engagement (Herrmann,

2013; Fidalgo-Blanco et al., 2016). Another example

of an online course design approach is the ELED

framework (Czerkawski, 2016) but as Czekawski et

al., write in their paper: “Student engagement in

online learning environments is a relatively new

problem for instructional designers and requires more

empirical research to advance the knowledge base.”

A previous study by Leeds et al., (2014) show that

many of the attempted and currently used retention

strategies in online courses are on their own

insufficient, or at least the results and effects on

student retention are inconclusive. The call for more

empirical evidence by Czerkawski (2016), is

something this study will answer.

2.4 Case Study: The UNIPS

Environment

Our case study platform is called UNIPS, which is an

acronym from the words University Pedagogical

Support. Since the site launch in autumn 2015 until

spring 2017, the three first courses were completed all

together over 334 times. All courses can be accessed

from the front page https://unips.fi, which is shown in

Figure 1. The courses, or modules as we often refer to

them, are called Lecturing & Expertise, Becoming a

Teacher and How to Plan my Teaching. Each of the

three above mentioned modules consists of an

individual task period and a group study period. In the

individual task period, students are tasked with

studying all the course material, which consist of

videos, scientific articles and small exercises, and

then write an essay of 1000-1500 words on a topic

related to the course. The estimated time required to

complete the first task is 12-14 hours. All students

who return an acceptable essay are then added to the

group study period, where they comment and reflect

on each other’s essays, and embark on discussions.

The teamwork period is moderated by the course

instructor, but the instructor does not participate in the

conversations unless necessary. The time reserved for

the teamwork period is 16 hours, but in reality we

have estimated that students spend no more than 4

hours on average on the discussions.

Figure 1: The frontpage of the UNIPS environment.

In the group work period of the UNIPS modules

the students study collaboratively on Google Drive

where they introduce themselves and attach their

essays for peer feedback and discussion. Sense of

presence affects the way students interact with each

other. According to Meyer (2014) it allows

individuals to speak freely and comfortably in a

discussion, and they are more willing to reveal their

personality. This contributes to increased student

engagement based on previous studies (Herrmann,

2013).

We gathered data on how many students enrolled

to the courses and how many students finally

completed the courses. During pilot testing in 2015

we noticed that adding small and easy tasks had a

positive effect on students’ retention. To test this

further, in autumn 2017 we introduced a pre-course

task called “the first task” to the beginning of the

courses before the individual task, and also a “final

task” to the end of all three courses after the group

study period. We wanted to figure out if this change

had an effect on the numbers on how many of the

enrolled students passed the courses. Our hypothesis

was, that dropout rates were higher in the beginning,

and much lower towards the end of the course. We

suspected that besides students who are initially more

motivated to complete the course, students who

successfully complete tasks during the course are

more engaged.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

590

3 METHOD

This study uses a mixed method approach in order to

obtain a holistic understanding on adult student

motivation and engagement in online courses. Firstly

we summarize the key factors affecting student

engagement from previous studies, and glance

through how well these are taken into account in our

course design. Due to the fact that even our initial

student dropout rate of 55% was significantly lower

than the over 87% from most popular MOOCS (Onah

et al. 2014), our hypothesis is that the case online

courses should be designed quite well according to

the suggestions from literature.

Next we go through quantitative data collected

from three UNIPS modules Lecturing & Expertise,

Becoming a Teacher and How to Plan my Teaching

over the years 2015-2017 to see how student dropout

rates evolved after adding a pre-and post-test to our

courses. Additionally we take a look at differences

between faculties, student age and if the student is a

doctoral student or a member of university staff.

3.1 Case Study Platform Design

Based on our hypothesis that low student retention

indicates lower engagement and hence lower

motivation, we explore how to improve student

retention, as it is the most clearly observable

quantitative statistic. We conclude from previous

studies the following four factors to focus on:

1. Instructors role (Ma et al. 2015; Goh et al.,

2017)

2. Technical aspects: usability of the platform,

quality of the study materials. (Onah et al., 2014;

Swan, 2001)

3. Perceived relevance of the course (Park and

Choi, 2009)

4. Support the learner gets from peers (Costley and

Lange, 2018, 69; Hew et al., 2016)

Using the information we have on our course design,

derived from the existing UNIPS solution

https://unips.fi and previous work (Laato et al., 2018)

we go through each of the four factors and evaluate

how they are present in the actual course

implementation, and also evaluate if and how they

could be improved upon.

3.2 Quantitative Analysis

For the quantitative data collection we create five

checkpoints between course enrolment and course

passing to figure out the instances where students

drop out. These checkpoints are unevenly scattered

across the course in all our three case modules, and

are situations where students are given a strict

deadline to return a task, otherwise they are marked

as dropouts. The five checkpoints are the following:

1. Students who enroll to the course, but never

complete the first task.

2. Students who complete the first task (pre-course

survey), but never sign in to the course Moodle

page.

3. Students who have signed in to Moodle, but who

never return the individual task.

4. Students who have returned the individual task,

but don’t participate in the first part of the

teamwork period.

5. Students who successfully complete the

teamwork period, but who do not complete the

final task.

Students who successfully manage to go through all

five checkpoints passed the course. Data with the

checkpoints was gathered from two instances in

autumn 2017 and spring 2018.

4 RESULTS

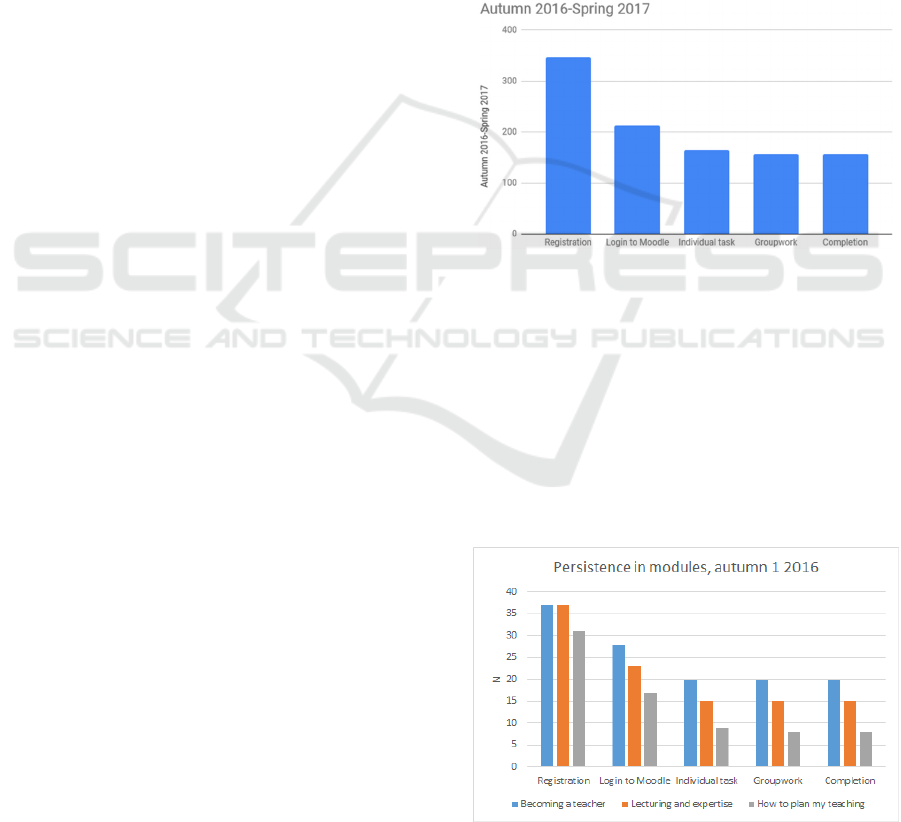

From autumn 2016 until spring 2017 our UNIPS

(previous name UTUPS) modules had a cumulative

dropout rate of 55% across the three modules. These

statistics can be seen in Figure 2. The course clear

rates are significantly better than the reported below

13% pass rate of popular MOOC’s (Onah et al.,

2014). One of the reasons for this is that the courses

are open and visible for everyone to observe, so there

is no need to enrol just to be able to look at the

materials. As for the other reasons, we will now

proceed to presenting our findings on our course

design based on the 4 key factors identified and listed

in the Method-section.

Figure 2: The dropout rates of three UNIPS modules during

the years 2016-2017.

Minimizing the Number of Dropouts in University Pedagogy Online Courses

591

4.1 Course Design Evaluation

(1) The instructors’ role in our modules is always the

same. To accept enrolments, to welcome students to

the course via email, to inform of them how to enter

Moodle, and then use Moodle to communicate

deadlines for each task and to remind students of

approaching deadlines. Hew et al., (2016) stress the

point that the instructor should be passionate about

the course, as the enthusiasm will show through to the

students and encourage them. The enthusiasm,

however, is very difficult to objectively measure or

evaluate. One approach is to measure the frequency

of communication between the instructor and the

students. In our case over the observed period (2016-

2018) the fixed amount of emails sent to students

during the one month course was six without pre-test

and eight with the pre-test. In addition the instructor

contacted students through the Moodle discussion

forums and occasionally reminded students who

failed to meet deadlines that they had been given a

few extra days to complete a task. The instructor also

always replied within a day to all inquiries students

sent regarding the course.

(2) The platform usability and design are discussed

more in depth in our previous work (Laato et al.,

2018). The basic pedagogical principles aimed to

make the user experience as smooth and as engaging

as possible are the following:

• Concise design

• Use of multimedia resources

• Short snippets of information

• Clear categorisation of materials

(3) How the students perceive the relevance of the

course can be measured in multiple stages: the first

impression, during studies and after completing the

course. In our case example the courses were directly

aimed at our university employers and doctoral

students with teaching duties, and also marketed as

such. This probably increased the perceived

relevance.

(4) In our case a teamwork period was included in all

three modules to answer the demand of feeling social

presence during studies. In the realm of higher

education, where students are quite familiar with the

used learning methods, the role of the instructor does

not necessarily have to be a big one in facilitating the

conversations among students.

We can conclude that all the four key factors

identified in previous studies as indicators of a

successful online course are present in our case. In

order to extend our understanding of students’

engagement and motivation, we now continue to the

quantitative analysis of student retention.

4.2 Quantitative Data on Student

Retention

To find out whether the pre- and post-test affect

student retention, we have two data groups. First, we

have data from autumn 2016 until spring 2017

collected from our modules without the pre-and post-

tests. Overall we had 346 students registering to our

courses with 156 students completing them. Figure 3

demonstrates the individual phases where students

forfeited their participation to the courses.

Figure 3: Phases where students withdraw from university

pedagogy online courses.

We observe the clearest spike right after

registration, as from 346 registered students only 213,

roughly 62% came to Moodle. This contradicts our

hypothesis that the most time consuming task

(individual task period) would be the one where

majority of students would leave the course. Instead,

what seems likely in light of this data is that the longer

students participate in the course, the more likely they

are to retain their participation.

Figure 4: Breakdown of student persistence by module in

autumn 1 module of 2016.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

592

Another phenomenon we wanted to take a look at

was if there is an observable difference in students’

engagement between our three modules. Figure 4

shows the case of autumn 2016 modules. The only

difference in student retention can be observed

between the first two phases: registration and signing

up to Moodle. 37 students signed up for both

Becoming a teacher and Lecturing and Expertise, but

28 and 23 students registered in Moodle respectively.

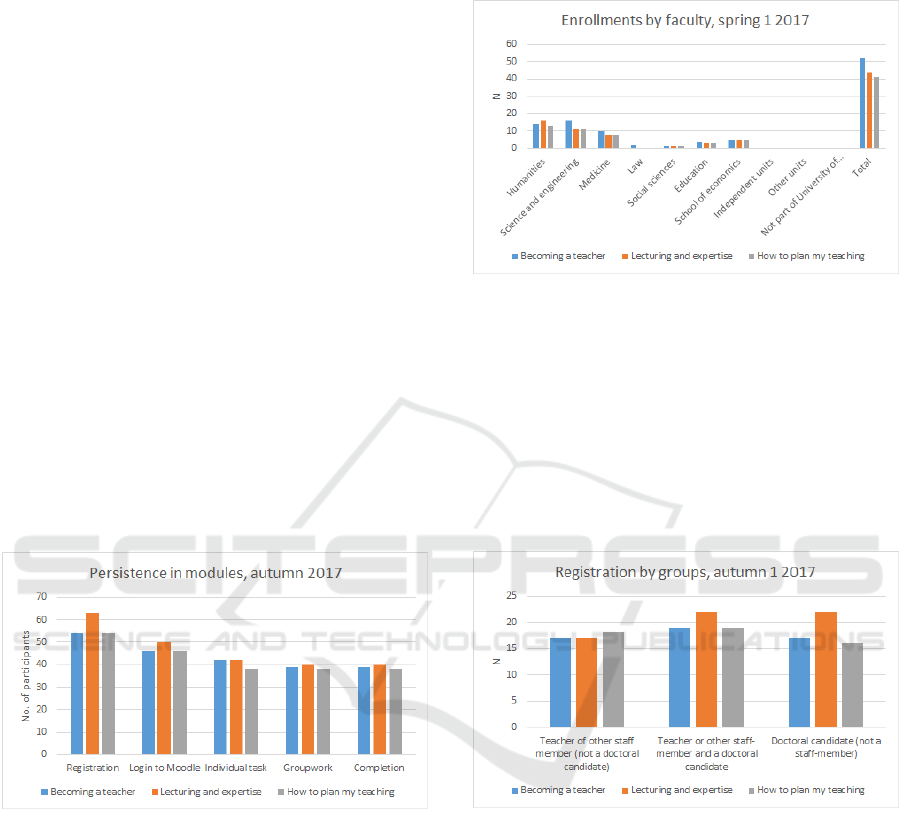

Adding to this data we have Figure 5 showing student

participation in the three modules from autumn 2017,

which is also our first instance with the pre- and post-

tests present. Based on the data presented in Figure 5,

we can conclude that there is no notable difference in

student retention between our three case modules.

Comparing the graphs Figure 3 and Figure 5 we

see a clear difference in the student dropout pattern.

Instead of a huge spike between registration and

joining Moodle, we now observe a much smoother

curve. This is also seen clearly on the overall course

clear rate, as in our first case the clear rate was only

45%, after the introduction of the pre-and post-tests

the clear rate climbed all the way up to 66%! These

results indicate that the very beginning of the course

is extremely important in order to engage students

and increase overall course retention.

Figure 5: Showing student persistence in the three case

modules in autumn 2017 with the pre-and post-tests

enabled.

Next we take a look at the demographics. Each of

our case course participants is either a university

employee or a doctoral student. As we offer the online

courses to all faculties, we had the unique opportunity

of measuring which faculties inside our university

were the most active in participating in the

pedagogical studies. It turns out as we can see from

Figure 6 that Humanities, Science & Engineering and

Medicine were the most active out of the seven main

faculties in our university. The faculty of Law on the

other hand had the fewest participants to the UNIPS

courses, which can partially be explained by the fact

that if measured by the number of employees, it is

also the smallest out of the seven faculties.

Figure 6: Students who enrolled to the UNIPS courses in

spring1, 2017 sorted by faculty.

Finally we take a look at the role of the students

to see sorted by module. No single module seemed to

be significantly popular over others among any group

of students. We could not either see any notable

differences in engagement or dropout rate based on

whether a student was a staff member or a doctoral

student. The role or status of the students is displayed

in Figure 7.

Figure 7: The current status of students who registered to

the UNIPS modules.

5 DISCUSSION

Perhaps the most interesting part in our results was

the improvement observed in student retention after

introducing pre-and post-tests to our courses. This

finding is in line with Evans et al., (2016, 209) finding

that students are more likely to complete a MOOC

course if they have completed a pre-course survey.

According to Evans et al., early engagement in

courses provides a strong predictor of sustained

engagement that leads to course completion. This

study confirms this observation in the realm of

Minimizing the Number of Dropouts in University Pedagogy Online Courses

593

university pedagogy online courses where students

are all either doctoral students or university staff

members.

Other factors like huge tasks, home faculty or the

status of the student did not have an observable

impact on retention. Course design most likely plays

a big role in general as previous studies suggest

(Fournier, 2015; Czerkawski, 2016), but as our 3 case

courses were constructed according to best practises

found in previous studies and were similar to each

other, no notable differences were found in retention

rates among the three case courses. Yang et al.,

(2013) show that at least in some cases social factors

within a MOOC and outside it affect student retention

rates, but in our case we observed only a few rogue

student quitting in the teamwork period with the

outstanding majority completing the course after

passing the individual task period and the half way

mark.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this study we looked up previous studies to find out

factors influencing student engagement and retention

in online courses. We found four key factors and

compared our case course design to these. We then

analysed student persistence during three online

courses and identified the stages when students

withdraw from the course. We did not examine the

possible extrinsic or intrinsic motivations students

have to continue studying the modules. Instead, the

focus was on online behaviour that can be traced in

the UNIPS platform and Moodle. The main

contribution of this study is that it provides empirical

evidence to support the previously stated theory that

the early stages of an online course are the most

crucial to the overall student engagement (Evans et

al., 2016).

In light of findings from this study, the next step

for us to improve our existing courses is to focus on

the beginning of our modules. How can we welcome

all students in a way they feel motivated and engaged

from the very beginning? What factors are there in the

very beginning of an online course that turn some

students away? In addition we are going to expand

our SPOC style courses to MOOC’s, and offer them

to a much larger audience. This will allow us see if

the findings of this case study are transferable to

outside our context. One final aspect that could be

explored in further research is why students decide to

study online. University pedagogy courses are also

available as synchronous, face-to-face teaching at the

University of Turku. However, online modules that

allow complete distance learning are popular among

students.

REFERENCES

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L.

(2009). Adolescent behavioral, affective, and cognitive

engagement in school: Relationship to dropout. Journal

of school Health, 79(9), 408-415.

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Fallu, J. S., & Pagani, L. S.

(2009). Student engagement and its relationship with

early high school dropout. Journal of adolescence,

32(3), 651-670.

Brent J. Evans, Rachel B. Baker, Thomas S. Dee:

Persistence Patterns in Massive Open Online Courses

(MOOCs). The Journal of Higher Education, Volume

87, Number 2, March/April 2016, pp. 206-242

(Article). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2016.0006

Broadbent, J., & Poon, W. L. (2015). Self-regulated

learning strategies & academic achievement in online

higher education learning environments: A systematic

review. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 1-13.

Cochran, J. D., Campbell, S. M., Baker, H. M., & Leeds, E.

M. (2014). The role of student characteristics in

predicting retention in online courses. Research in

Higher Education, 55(1), 27-48.

Costley, J., & Lange, C. (2018). The Moderating Effects of

Group Work on the Relationship Between Motivation

and Cognitive Load. The International Review of

Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(1).

Czerkawski, B. C., & Lyman, E. W. (2016). An

instructional design framework for fostering student

engagement in online learning environments.

TechTrends, 60(6), 532-539.

Kahu, E. R., Stephens, C., Leach, L., & Zepke, N. (2013).

The engagement of mature distance students. Higher

Education Research & Development, 32(5), 791-804.

Deming, D. J., Goldin, C., Katz, L. F., & Yuchtman, N.

(2015). Can online learning bend the higher education

cost curve?. American Economic Review, 105(5), 496-

501.

Evans, B. J., Baker, R. B., & Dee, T. S. (2016). Persistence

patterns in massive open online courses (MOOCs). The

Journal of Higher Education, 87(2), 206-242.

Fidalgo-Blanco, Á., Sein-Echaluce, M. L., & García-

Peñalvo, F. J. (2016). From massive access to

cooperation: lessons learned and proven results of a

hybrid xMOOC/cMOOC pedagogical approach to

MOOCs. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), 24.

Fournier, H., & Kop, R. (2015). MOOC learning experience

design: Issues and challenges. International journal on

E-Learning, 14(3), 289-304.

Goh, W., Ayub, E., Wong, S. Y., & Lim, C. L. (2017,

November). The importance of teacher's presence and

engagement in MOOC learning environment: A case

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

594

study. In 2017 IEEE Conference on e-Learning, e-

Management and e-Services (IC3e) (pp. 127-132).

IEEE.

Gütl, C., Rizzardini, R. H., Chang, V., & Morales, M.

(2014, September). Attrition in MOOC: Lessons

learned from drop-out students. In International

workshop on learning technology for education in

cloud (pp. 37-48). Springer, Cham.

Henderikx, M. A., Kreijns, K., & Kalz, M. (2017). Refining

success and dropout in massive open online courses

based on the intention–behavior gap. Distance

Education, 38(3), 353-368.

Henrie, C. R., Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2015).

Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated

learning: A review. Computers & Education, 90, 36-53.

Herrmann, K. J. (2013). The impact of cooperative learning

on student engagement: Results from an intervention.

Active learning in higher education, 14(3), 175-187.

Hew, K. F. (2016). Promoting engagement in online

courses: What strategies can we learn from three highly

rated MOOCS. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 47(2), 320-341.

Hoffman, M. S. (2018). Faculty Participation in Online

Higher Education: What Factors Motivate or Inhibit

Their Participation?. In Teacher Training and

Professional Development: Concepts, Methodologies,

Tools, and Applications (pp. 2000-2013). IGI Global.

Kahu, E. R., Stephens, C., Leach, L. & Zepke, N. (2013)

The engagement of mature distance students, Higher

Education Research & Development, 32:5, 791-804,

DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2013.777036

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2016). Higher education

and the digital revolution: About MOOCs, SPOCs,

social media, and the Cookie Monster. Business

Horizons, 59(4), 441-450.

Karim, M. N. & Behrend, T. S. (2015) "Controlling

Engagement: The Effects of Learner Control on

Engagement and Satisfaction" In Increasing Student

Engagement and Retention in e-learning Environments:

Web 2.0 and Blended Learning Technologies. https://

doi.org/10.1108/S2044-9968(2013)000006G005

Katrina A. Meyer (2014): Student Engagement in Online

Learning: What Works and Why. ASHE Higher

Education Report, Volume 40, Issue 6, pp. 1–114.

Ke, F. & Xie, K. (2009): Toward deep learning for adult

students in online courses. The Internet and Higher

Education, Volume 12, Issues 3–4, December 2009,

136-145. DOI: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.08.001

Kuh, G. D. (2003). What we're learning about student

engagement from NSSE: Benchmarks for effective

educational practices. Change: The Magazine of Higher

Learning, 35(2), 24-32.

Laato, S., Salmento, H., & Murtonen, M. (2018).

Development of an Online Learning Platform for

University Pedagogical Studies-Case Study. In CSEDU

(2) (pp. 481-488).

Lee, Y. and Choi, J., 2011. A review of online course

dropout research: Implications for practice and future

research. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 59(5), pp.593-618.

Leeds, E., Campbell, S., Baker, H., Ali, R., Brawley, D., &

Crisp, J. (2013). The impact of student retention

strategies: An empirical study. International Journal of

Management in Education, 7(1-2), 22-43.

Liu, Z., Pinkwart, N., Liu, H., Liu, S., & Zhang, G. (2018).

Exploring Students’ Engagement Patterns in SPOC

Forums and their Association with Course

Performance. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics,

Science and Technology Education, 14(7), 3143-3158.

Ma, J., Han, X., Yang, J., & Cheng, J. (2015). Examining

the necessary condition for engagement in an online

learning environment based on learning analytics

approach: The role of the instructor. The Internet and

Higher Education, 24, 26-34.

Martínez-Muñoz, G., & Pulido, E. (2015, March). Using a

SPOC to flip the classroom. In Global Engineering

Education Conference (EDUCON), 2015 IEEE (pp.

431-436). IEEE.

Meyer, K. A. (2014). Student engagement in online

learning: What works and why. ASHE Higher

Education Report, 40(6), 1-114.

Murphy, C. A., & Stewart, J. C. (2017). On-campus

students taking online courses: Factors associated with

unsuccessful course completion. The Internet and

Higher Education, 34, 1-9.

Onah, D. F., Sinclair, J., & Boyatt, R. (2014). Dropout rates

of massive open online courses: behavioural patterns.

EDULEARN14 proceedings, 5825-5834.

Park, J. H., & Choi, H. J. (2009). Factors influencing adult

learners' decision to drop out or persist in online

learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,

12(4).

Shelton, B. E., Hung, J. L., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2017).

Predicting student success by modeling student

interaction in asynchronous online courses. Distance

Education, 38(1), 59-69.

Stracke, C. M. (2017, July). Why we need High Drop-out

Rates in MOOCs: New Evaluation and Personalization

Strategies for the Quality of Open Education. In

Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 2017 IEEE

17th International Conference on (pp. 13-15). IEEE.

Swan, K. (2001). Virtual interaction: Design factors

affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in

asynchronous online courses. Distance education,

22(2), 306-331.

UNIPS (University Pedagogical Support), online learning

platform, https://unips.fi, fetched 7.12.2018

Vayre, E., & Vonthron, A. M. (2017). Psychological

engagement of students in distance and online learning:

Effects of self-efficacy and psychosocial processes.

Journal of Educational Computing Research, 55(2),

197-218.

Watted, A., & Barak, M. (2018). Motivating factors of

MOOC completers: Comparing between university-

affiliated students and general participants. The Internet

and Higher Education, 37, 11-20.

Wiebe, E. & Sharek D. (2016): eLearning. In O’Brien, H.

& Cairns, P. (eds.), Why Engagement Matters. Springer

International Publishing Switzerland.

Willging, P. A., & Johnson, S. D. (2009). Factors that

Minimizing the Number of Dropouts in University Pedagogy Online Courses

595

influence students' decision to dropout of online

courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks,

13(3), 115-127.

Yang, D., Sinha, T., Adamson, D., & Rosé, C. P. (2013,

December). Turn on, tune in, drop out: Anticipating

student dropouts in massive open online courses. In

Proceedings of the 2013 NIPS Data-driven education

workshop (Vol. 11, p. 14).

Yang, D., Baldwin, S. & Snelson, C. (2017) Persistence

factors revealed: students’ reflections on completing a

fully online program, Distance Education, 38:1, 23-36,

DOI: 10.1080/01587919.2017.1299561

Yoo, Sun Joo & Huang, Wenhao David (2013): Engaging

Online Adult Learners in Higher Education:

Motivational Factors Impacted by Gender, Age, and

Prior Experiences, The Journal of Continuing Higher

Education, 61:3, 151-164, DOI: 10.1080/07377363.

2013.836823

Zhang, D., Zhao, J. L., Zhou, L., & Nunamaker Jr, J. F.

(2004). Can e-learning replace classroom learning?.

Communications of the ACM, 47(5), 75-79.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

596