Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU

Product Label

Anika Linzenich, Katrin Arning and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57, 52074 Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU), Social Acceptance, Trust, Product Labeling, Purchase Intention and

User Diversity.

Abstract: Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU) is a technological approach to reduce CO

2

emissions and fossil

resource depletion by using CO

2

, e.g., from power plants, as feedstock for the manufacturing of products.

Since CCU products are novel and have a low public awareness, a specific product label might be helpful to

inform the public about and build trust in CCU products. However, product labels should not only target at

the merchantability of novel products but should integrate users’ information needs and their requirements

towards trust and reliability of the product and the production process. In an online survey with 147 German

laypeople, requirements for a trusted CCU label were investigated to derive recommendations for a successful,

trust-building label and certification process design. Results revealed a positive trust in the CCU label. CCU

label trust tended to be higher in persons with higher trust in other people and product labels in general.

Purchase intentions for labeled CCU products were increased by a higher CCU label trust and environmentally

aware behaviors and decreased by a higher technical self-efficacy. Trusted sources informing about the label

were identified as focal point for increasing label trust at this early stage of market entering for CCU products.

1 INTRODUCTION

To address the global challenge of climate change,

various measures are taken worldwide to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions and fossil resource use

(UNEP, 2017). One technological approach to re-use

CO

2

emissions from industrial sources, e.g., power

plants, and decrease fossil resource depletion is

carbon capture and utilization (CCU). There is a large

variety of carbon capture and utilization options, such

as the production of urea, fuels, or plastic products

(Zimmermann and Schomäcker, 2017). A main

advantage of CCU is that the consumption of fossil

resources in plastic product manufacturing can be

reduced because CO

2

is used as a substitute for fossil

carbon sources (Von der Assen and Bardow, 2014).

A decisive factor for the successful market

introduction of CO

2

-derived products will be their

favorable acceptance by the public. This includes not

only a passive tolerance of the CCU technology

infrastructure but also an active willingness to buy

and use CCU products (Jones et al., 2017). To raise

public awareness of CCU and enable laypeople an

informed decision whether or not they want to buy a

CCU product instead of a conventionally produced

alternative, a CCU product label could be used to

mark CCU products and highlight the differences to

conventional manufacturing.

Recently, there have been efforts to develop seals

of approval for products (e.g., Olfe-Kräutlein et al.,

2016). However, these single efforts are mainly

limited to a public discourse of the topic without

substantial empirical base to validate the

appropriateness of such seals. It is mandatory for a

successful and accepted label to include a theoretical

knowledge but also an empirical validation of how

label trust is constituted and how an accepted label

certification process looks like.

Instead of merely focusing on the merchantability

of a product, it is reasonable to understand in a first

step, which information and communication needs

are prevailing at all and how and why the

characteristics of novel products are perceived as

risky or beneficial by the consumers. Thus, prior to

investigating the specific design of a CCU label (how

to display which information, preferred color scheme

and design elements), the framework conditions for a

trusted label design and certification process need to

be determined. Therefore, the present study aims at

identifying requirements for such a trust-building

CCU product label. Using data from an online survey,

the level of trust in a CCU label and the influence of

58

Linzenich, A., Arning, K. and Ziefle, M.

Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU Product Label.

DOI: 10.5220/0007690100580069

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2019), pages 58-69

ISBN: 978-989-758-373-5

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

CCU label trust on the purchase intention for labeled

CCU products are investigated. Moreover, it is

examined which user- and label-related factors

impact CCU label trust and the purchase intention for

labeled CCU products.

The paper is structured as follows: In Section 1.1

and 1.2, an overview is given on the state of research

on CCU product acceptance and on the importance of

trust for a successful product label. Subsequently, the

study’s methodological approach, the sample, and the

procedure of data analysis are presented (Section 2).

In Section 3, the study findings are described. Finally,

results are discussed and recommendations for a trust-

building CCU label are derived (Section 4).

1.1 Social Acceptance and Awareness

of CCU Products

CCU products are innovative products which require

a favorable social acceptance for their successful

market adoption (Jones et al., 2017). Although

previous studies have revealed a positive general

acceptance of the CCU technology and products,

awareness of CCU was found to be low (e.g., Arning

et al., 2019; Offermann-van Heek et al., 2018). One

way to increase the public awareness of CCU

products are tailored information concepts, which

have to be timely integrated to be effective (Bögel et

al., 2018). Especially as CCU products do not

observably differ from conventional products (only

the manufacturing process distinguishes them, Von

der Assen and Bardow, 2014), a possible approach to

both raise the public awareness of CCU products and

foster trust in CCU industry and products is an

adequate product labeling. So far, studies on CCU

acceptance have mainly focused on benefit and risk

perceptions of the CCU technology and products and

on trust and distrust in stakeholders involved in the

implementation of CCU technologies, such as CCU

industry, government, and research institutions (e.g.,

Arning et al., 2019; Offermann-van Heek et al.,

2018). Although past research has identified the need

for raising public awareness of and clearly labeling

CCU products (Offermann-van Heek et al., 2018;

Olfe-Kräutlein et al., 2016; Van Heek et al., 2017), no

study has yet looked into laypeople’s requirements

for a successful and informative CCU product label.

1.2 The Importance of Trust in

Product Label Design

Missing trust in stakeholders has been revealed as

crucial barrier to the successful introduction of energy

technologies and innovative products (Huijts et al.,

2012). Trust is a multidimensional concept with no

uniform definition across research disciplines. The

trust framework of McKnight and Chervany (2001),

originally explaining trust in the ICT- and e-

commerce context, differentiates between trust as

disposition, belief, intention, and behavior: While

trust disposition refers to the general trust a person

has in other people (i.e., the willingness to depend on

general others), trusting beliefs refer to the trustor’s

(= the person who trusts) evaluations of the trustee’s

characteristics (trustee = the person or institution who

is to be trusted). A trustee is evaluated as trustworthy

to fulfill a task if this person is believed to possess the

ability or power to fulfill the task (competence), to be

willing to act in the trustor’s interest (benevolence),

to be truthful and to keep promises (integrity), and to

act consistently (predictability). On the basis of one’s

trusting beliefs, trusting intentions are developed,

which then lead to trust-related behavior. In line with

other previous research (e.g., Van de Walle and Six,

2014), distrust is distinguished from trust as the

opposite, but separate concept: Hence, trust and

distrust can exist to a differing extent at the same

time, depending on the specific evaluation of a

situation.

Past research on credibility of information

sources in the CCU context revealed that trust in CCU

industry and governmental institutions was on a

medium level and received lower trust ratings

compared to research institutions and NGOs

(Offermann-van Heek et al., 2018). Further,

consumers request to be informed whether a product

was manufactured using the CCU or conventional

technology, even if the CCU alternative does not

noticeably differ from the conventional products, and

withholding this information might thus evoke

distrust (Offermann-van Heek et al., 2018; Van Heek

et al., 2017). If tailored to laypeople’s requirements,

a CCU product label could act as a trust-building

measure by transparently informing about CCU

products and their characteristic features.

One approach to make production-related

characteristics “visible” is the eco-label. Eco-labels

inform buyers about a product’s environmental

qualities (Atkinson and Rosenthal, 2014). It was

found that eco-labels can positively impact consumer

purchase decisions for labeled products (e.g., Feucht

and Zander, 2018) and they are the most preferred

source for environmental information about a product

(European Commission, 2013).

As the purpose of a product label is to convey the

most essential information at a glance within a very

limited space, it needs to be carefully designed.

Integrating laypeople’s requirements and wishes in

Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU Product Label

59

the development of product labels is crucial to make

sure the label is comprehensible, unambiguous, and

regarded as trustworthy. Otherwise, a newly

introduced product label might confuse consumers,

get lost in the shuffle of existing labels, or create

distrust (e.g., Moon et al., 2017). Studies on eco-label

acceptance identified argument specificity (i.e.,

detailed information about the environmental

qualities of the product) and additional information

on the label (e.g., about the label meaning and

certification conditions and regulations) as

requirements for an accepted and trusted product

label (Atkinson and Rosenthal, 2014; Emberger-

Klein and Menrad, 2018). Especially for carbon

labels it was difficult for laypeople to comprehend the

presented label information and to put it into

perspective (Upham et al., 2011). In a study by the

European Commission (2013), most respondents

believed that existing eco-labels provided not enough

and/or not sufficiently clear environmental

information about labeled products. Also, unknown

labels were found to elicit low trust (e.g., Sirieix et

al., 2013).

Beyond the specific label design and displayed

information, the process of label certification is a

factor that also needs to be carefully considered.

Particularly when product manufacturers or

supermarket brands award a label themselves,

consumers have been suspicious (particularly in

Germany), whereas governmental certification

evoked higher trust and was preferred to producers’

claims (Atkinson and Rosenthal, 2014; European

Commission, 2013; Sirieix et al., 2013). In a previous

study on CCU acceptance, where a seal of approval

for CCU products was assessed as important for trust

in the CCU industry, interviewees mentioned the

requirement of label source: A certification by

independent sources such as governmental

institutions or specific institutes was preferred

(Offermann-van Heek et al., 2018).

Furthermore, it is important for a successful

implementation of a product label to identify

consumer groups which are responsive to the label

and which are reluctant in trusting the label. Yet, the

impact of user factors (person-related characteristics

such as sociodemographic factors and general

attitudes) on attitudes towards eco-labels is not

sufficiently clear (Waechter et al., 2015). Individual

factors associated with attention to and preference for

eco-labels were, for example, young age, higher

education, pro-environmental attitude, knowledge

about eco-labels, and personal innovativeness related

to eco-labels (e.g., Brécard et al., 2012; Thøgersen,

2000; Thøgersen et al., 2010).

Results on the influence of gender on eco-label

attitudes were mixed: Whereas Brécard et al. (2012)

found that men are more willing to adopt eco-labels,

Sønderskov and Daugbjerg (2011) revealed a higher

eco-label trust for women. Other influence factors for

eco-label trust identified by Sønderskov and

Daugbjerg (2011) were a younger age, a higher

environmental awareness, and a higher general trust

in other people and institutions.

1.3 Research Questions

The present research is the first systematic attempt to

investigate laypeople’s requirements for a trust-

building product label for CO

2

-derived products. In

order to explore trust in a label for CCU products and

to identify requirements for fostering label trust, the

following questions were examined:

RQ1. Do laypeople trust in a CCU label?

RQ2. Does trust in the CCU label affect the

willingness to buy CCU products?

RQ3. Is trust in the CCU label affected by user

characteristics?

RQ4. Which factors related to label and certification

process design build trust in CCU product

labels?

2 METHODOLOGY

In the following section, the structure of the online

questionnaire and the survey sample are described.

2.1 Questionnaire Structure

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. An

overview of questionnaire items can be found in the

Appendix (Table A.1).

In the first part, demographic data (age, gender,

education) and attitudinal characteristics

(environmentally aware behavior, technical self-

efficacy, trust disposition, and self-reported

knowledge about CCU) were assessed. Respondents’

environmentally aware behavior was measured by six

items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) based on a study

conducted for the European Commission (2008) and

on Wippermann et al., (2008). Technical self-

efficacy, i.e., one’s general attitude towards

technology, was assessed by four items (Cronbach’

alpha = 0.90) from Beier (1999). Trust disposition

was measured using the 12-item-scale from

McKnight et al., (2002) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84).

Self-reported knowledge about CCU was covered by

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

60

four items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92) specifically

developed for the research topic: Respondents were

asked to evaluate their familiarity with different

aspects of carbon utilization (storage, utilization,

product spectrum), partly based on the scale used by

Arning et al., (2019). The scale was validated in pre-

studies.

The second part captured participants’ perception

of product labels in general and the CCU label in

particular. General trust in product labels was

measured using the item “I totally trust in product

labels.” To assess trust in the CCU label, a scale was

developed that covered essential trust dimensions

identified in McKnight and Chervany (2001) and

specified them for the topic of CCU labels. The scale

consisted of five items measuring trusting beliefs

(benevolence and integrity) related to the label

certification and the intention to trust a CCU product

label (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81). Items on CCU label

trust were developed based on an interview pre-study

and previous research on label trust (Moussa and

Touzani, 2008) and had been validated in pre-studies.

Also, the purchase intention for labeled CCU

products was measured by five items related to

actively searching for labeled CCU products,

preferring labeled CCU products to conventional

products, and the willingness to buy novel and

unfamiliar products marked by the CCU label

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87).

In the third part of the questionnaire, respondents

had to evaluate conditionals for trust and distrust in a

CCU product label (see Table A.2, Appendix). They

were asked which factors (related to the certification

process, the label design, and the provided

information) would foster their trust or distrust in a

CCU product label. The 14 trust- and 15 distrust

conditional items were derived from interviews with

laypeople and experts conducted prior to the study

and from the current state of research on eco-label

trust (see Section 1.2). Trust and distrust conditionals

were assessed separately since past research

identified trust and distrust to be separate concepts.

All questionnaire items were answered on six-

point Likert scales ranging from “do not agree at

all”(1) to “fully agree”(6). Accordingly, mean values

> 3.5 signify approval to and values < 3.5 indicate

rejection of a statement.

2.2 Sample

Data was collected online in fall 2017. The survey

link was disseminated by e-mail, discussion forums,

and social media. 186 respondents participated in the

study. They were not financially rewarded but

volunteered to participate. Excluding incompletes

and speeders (response time < 10 min), 147 data sets

remained for the analysis (response rate: 79.0%).

Participants’ age ranged between 17 and 70 years

(M = 33.3 years, SD = 13.2). 49.0% were female and

51.0% were male. 56.5% had a university degree or

higher, 27.9% a university entrance certificate, and

14.3% reported a secondary school diploma or lower

secondary school leaving certificate as highest

educational qualification, whereas 1.4% stated to

have another type of qualification.

The sample reported environmentally aware

consumption behaviors (M = 4.03, SD = 0.86), a

positive technical self-efficacy (M = 4.38, SD = 1.19)

and a positive trust disposition, i.e., general trust in

other people (M = 3.80, SD = 0.60). Self-assessed

knowledge about the CCU technology and products

was low (M = 2.27, SD = 1.17): 84.4% felt rather

uninformed (M < 3.5), whereas 15.6% felt (rather)

knowledgeable about the topic of CCU (M ≥ 3.5).

2.3 Data Analysis

Mean values for all constructs with multiple item-

measurement were computed. Data was analyzed

using descriptive and inference statistics. To compare

mean values for label trust ratings (related to the CCU

label and product labels in general) and purchase

intention for labeled CCU products, t-Tests for paired

samples were used. If multiple t-Tests were

conducted, the adjusted value for statistical

significance was considered. A principal component

analysis was conducted to explore the factor structure

in the questionnaire and to identify (dis)trust factors

in the CCU label context. Finally, the influence of

user factors and (dis)trust factors on CCU label

perceptions was investigated using regression

analyses. Regression diagnostics were carried out to

determine if model analysis assumptions were

fulfilled. Multicollinearity (i.e., biasing effects due to

intercorrelating factors, Hair, 2011) could be ruled

out because VIF values were below 10 and tolerance

values above 0.2 for all predictors used in the model.

3 RESULTS

First, results for trust in the CCU label and purchase

intention for labeled CCU products are reported.

Then, the effect of user factors on CCU label trust and

intention to buy CCU products is examined. In a last

step, the impact of label- and certification process-

related factors on CCU label trust is investigated.

Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU Product Label

61

3.1 CCU Label Trust and Purchase

Intention for CCU Products (RQ1)

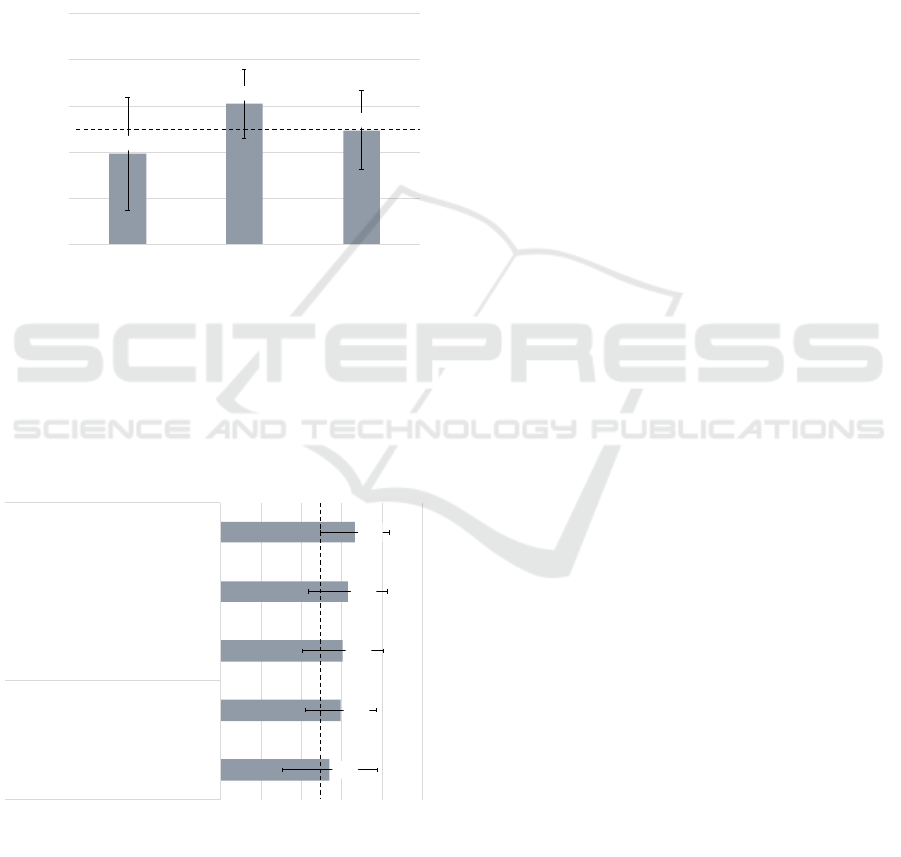

As Figure 1 shows, general trust in product labels was

rather low (M = 2.96, SD = 1.21). In contrast, trust in

a specific label for CCU products was positive and

significantly higher (M = 4.04, SD = 0.74;

t(146) = 12.77, p < 0.001). However, compared to

CCU label trust, the purchase intention for labeled

CCU products was neutral (M = 3.47, SD = 0.86) and

significantly lower (t(146) = -8.75, p < 0.001).

Figure 1: Ratings of general trust in product labels, trust in

the CCU product label, and purchase intention for labeled

CCU products (n = 147).

Examining CCU trust in more detail (see Figure 2), it

can be seen that both trusting beliefs (related to

benevolence and integrity) and trusting intentions

were rather positive.

Figure 2: Ratings of trusting beliefs and trusting intention

related to the CCU product label (n = 147).

In order to analyze whether trusting intention

significantly differed from trusting beliefs, mean

values were calculated over the three belief- and two

intention-items. Results showed that trusting beliefs

(M = 4.17, SD = 0.77) were on average significantly

more positive than the trusting intention related to the

CCU product label (M = 3.85, SD = 0.86;

t(146) = 6.10, p < 0.001).

3.2 Impact of User Factors on CCU

Label Trust and Purchase Intention

(RQ2 and 3)

To investigate how trust in the CCU label and

purchase intention for CCU products are developed,

it is also important to consider which person-related

factors (user factors) influence CCU label trust and

the intention to buy labeled CCU products. Therefore,

a stepwise regression analysis was run to examine

whether trust in a CCU label is impacted by user

factors (i.e., whether some groups are more trusting

of CCU product labels than other groups of persons).

The measured demographic and attitudinal variables

(age, gender, education, environmentally aware

behavior, technical self-efficacy, trust disposition,

self-assessed knowledge about CCU, and general

trust in product labels) were entered as independent

variables and trust in the CCU label as dependent

variable.

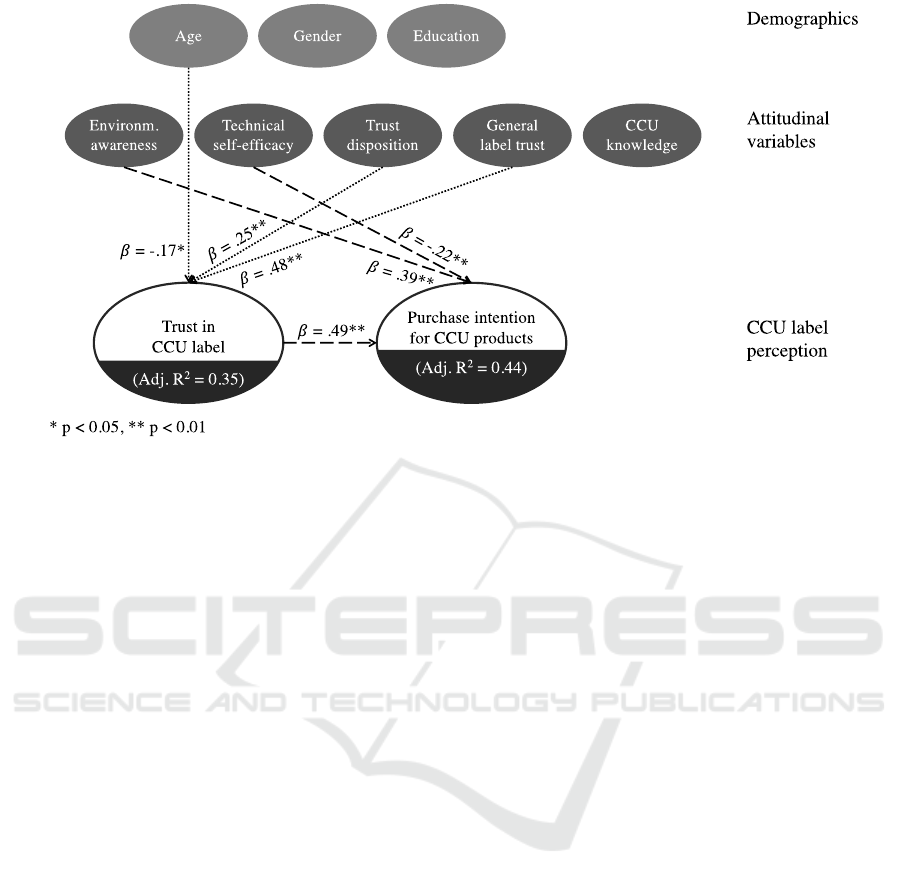

Results are displayed in Figure 3. It was found

that age, trust disposition, and general trust in product

labels significantly affected trust in the CCU label

and explained together 35.4% of variance in CCU

label trust (F(3,143) = 27.64, p < 0.001). All other

factors were excluded from the regression model,

meaning they did not significantly impact trust.

General trust in product labels was identified as

strongest driver of CCU label trust (𝛽 = .48,

p < 0.001), followed by trust disposition (𝛽 = .25,

p < 0.001): A higher trust in general others and in

product labels in general increased specific trust in

the CCU label. Moreover, a younger age was linked

to a higher trust in the CCU label (𝛽 = -.17, p < 0.05).

In a next step, influence factors for the intention

to purchase labeled CCU products were analyzed

using stepwise regression. Alongside demographics

and general attitudes, also the specific trust in the

CCU label was included as predictor and the purchase

intention was entered as criterion. The resulting

regression model (Figure 3) explained 43.8% of

variance in the intention to buy labeled CCU products

(F(3,143) = 38.86, p < 0.001). The sole variables

contributing significantly to purchase intention were

“trust in the CCU label” (𝛽 = .49, p < 0.001),

environmental awareness (𝛽 = .39, p < 0.001), and

technical self-efficacy (𝛽 = -.22, p < 0.001).

2.96

4.04

3.47

1

2

3

4

5

6

General trust

in product labels

Trust in CCU

product label

Purchase intention

for labeled CCU

products

Average trust rating ( min = 1, max = 6)

midpoint

3.71

3.98

4.04

4.16

4.33

1 2 3 4 5 6

Intention to use labeled CCU

products without concerns

Intention to trust

the CCU product label

Integrity - Information

displayed on the label is true

Benevolence - Good intentions

respecting consumers interests

Benevolence - Label shall

inform consumers

Trusting intention

Trusting beliefs

Average rating (min = 1, max = 6)

midpoint

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

62

Figure 3: Regression models for the impact of user factors on CCU label trust and purchase intention for labeled CCU products

(n = 147).

Whereas a higher CCU label trust and a more

environmentally aware behavior increased the

intention to buy labeled CCU products, a more

positive general attitude towards technology tended

to lower the purchase intention.

3.3 Trust and Distrust Factors

Impacting CCU Label Trust (RQ4)

So far, trust and purchase intentions for a CCU label

have been examined and it was analyzed to which

extent they are influenced by user factors. Still, it is

unclear if there are possibilities to increase (or barriers

which lower) the trustworthiness of the CCU label. To

identify trust- and distrust-building factors for CCU

labels, a principal factor analysis (PCA) was conducted

for the 29 (dis-)trust items to determine the factorial

construct structure (see Table A.2, Appendix).

Selection of factors retained in analysis was based

on two conditions: 1) visual diagnostics of the scree

plot (using the point of inflexion in the scree plot as

cut-off point), 2) Kaiser’s criterion (checking for

eigenvalues of factors > 1) (Field, 2009). Due to the

small sample size, only items with a factor loading >

.512 were retained (which is the cut-off for a sample

with n = 100, Field, 2009). Quality criteria for PCA

proved that the data matrix was suitable (Bartlett’s test

of sphericity p < 0.001) and that there was a high level

of sampling adequacy (KMO = .775) (Hair, 2011). The

obtained factorial structure (Table A.2, Appendix)

revealed five (dis)trust factors:

1. Unknown and private certifying organization

(distrust factor, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82)

2. Transparent and independent certification

process (trust factor, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76)

3. Information sources (trust factor, Cronbach’s

alpha = 0.76)

4. Provided label information (trust / distrust factor,

Cronbach’s alpha = 0.66)

5. Unusual label design (distrust factor, Cronbach’s

alpha = 0.80)

The five extracted dimensions explained 46.5% of the

total variance.

The first factor “unknown and private certifying

organization” was related to a private, dependent

organization awarding the label, which was unknown

to respondents and about which no information was

available (“unknown auditor”).

The second factor “transparent and independent

certification process” was comprised of transparent

awarding criteria and regulations for product controls,

transparent information about the CO

2

footprint of the

CCU product, and an independent certifying

organization that awards the label.

The third factor was related to “trusted sources”

informing respondents about the label (meaning how

respondents got in touch with the label, e.g., via

media coverage or friends).

The fourth factor referred to “information,” i.e.,

both the information provided on the label (extent of

information, reference to additional information) but

also available information about the certifying

organization were summarized.

Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU Product Label

63

The fifth factor concerned “label design”

(unusual label shape and design).

Most factors were exclusively trust or distrust

factors (they included only trust or distrust

conditionals). The only factor which consisted of both

trust and distrust conditionals was “provided label

information.”

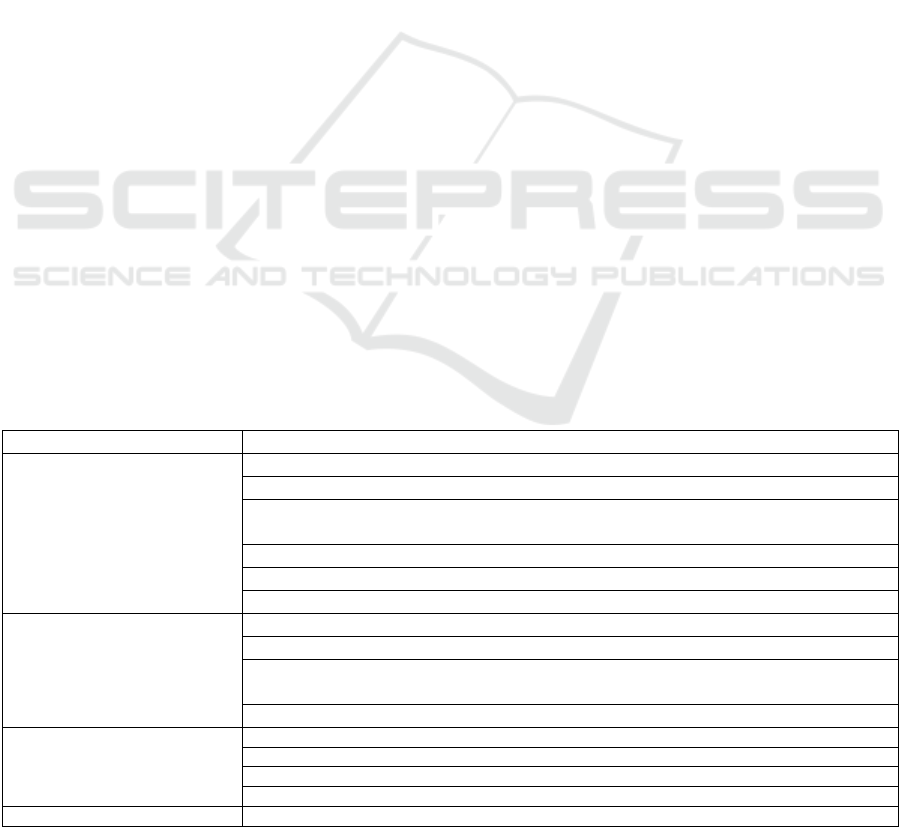

In a second step, mean values were calculated for

the five obtained (dis)trust factors to see which of

these factors participants evaluated as most relevant

for their trust or distrust in the CCU product label

(Figure 4).

Figure 4 shows that on a descriptive level all

factors were assessed as (rather) relevant for trust or

distrust in the CCU label except for the “unusual

label design,” which was rated as rather unimportant.

All differences in relevance ratings for the five factor

levels were statistically significant on a level of

p < 0.001 (except for the difference between

“unknown and private certifying organization” and

“provided label information” with p < 0.01).

Figure 4: Ratings of relevance of (dis)trust factors for

increasing (dis)trust in the CCU product label (n = 147).

To test whether the (dis)trust factors had a

statistically significant impact on CCU label trust and

purchase intention, stepwise regression analyses were

conducted using the five (dis)trust factors as input

factors and CCU label trust and purchase intention for

labeled CCU products as dependent variables.

The regression models (Figure 5) revealed that

both CCU label trust and intention to buy labeled

CCU products were affected by “information

sources” as strongest driver and purchase intention

for CCU products additionally by a “transparent and

independent certification process,” whereas the other

(dis)trust factors had no significant impact and were

excluded from the models. The “information

sources” factor explained 24.4% of variance in CCU

label trust (F(1,145) = 48.08, p < 0.001). With 16.1%,

“information sources” in combination with

“transparent, independent certification” explained a

comparably lower amount of variance in purchase

intention (F(2,144) = 15.01, p < 0.001).

Figure 5: Regression models for the impact of information

sources and transparent, independent certification on CCU

label trust and purchase intention (n = 147).

Given the relevance of information sources for

both CCU label trust and purchase intention, it should

be examined which sources of information are most

appropriate for fostering label trust. Mean values for

trust conditionals related to information sources are

displayed in Figure 6. As shown, respondents

evaluated “media” and “friends and acquaintances”

most positively. On the other hand, “political

information sources” and “famous label

ambassadors” were rather not seen as relevant to

increase one’s trust in the CCU label. All differences

between information sources were statistically

significant with p < 0.001 (except for the difference

between “media” and “friends and acquaintances”

with p < 0.01).

Figure 6: Ratings of relevance of information sources for

increasing trust in the CCU product label (n = 147).

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

4.1 Perception of and Trust in Labels

The present study investigated requirements for a trust-

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

64

building CCU label to raise public awareness of CCU

products and enable consumers an informed decision

whether they want to buy a CCU alternative instead of

a conventional product. Results revealed a positive

trust in the CCU label, but the purchase intention for

labeled CCU products was neutral.

Apart from identified trust levels, the present study

also allowed insights into the factorial structure of the

(dis)trust construct. (Dis)trust factors for CCU labels

were based on the dimensions “unknown and private

certifying organization,” “transparent and

independent certification process,” “sources

informing about the label,” “provided label

information,” and “unusual label design.”

Interestingly, the (dis)trust factors had a lower effect

on CCU label trust and purchase intention than user

factors. On a descriptive level, respondents evaluated

certifying organization, certification process and

monitoring, label information, and sources informing

about the CCU label as (rather) relevant for fostering

trust in the CCU label. However, it was revealed that

only the information sources disseminating

information about and familiarizing laypeople with the

CCU label did significantly impact both CCU label

trust and intention to buy products carrying the CCU

label. The purchase intention for labeled CCU products

was furthermore increased by a transparent and

independent certification process. This might be due to

the (currently) early phase of market entering of CCU

products. In the current study, respondents’ awareness

of the CCU technology and CCU products was very

low, which is in line with results from other recent

research (e.g., Offermann-van Heek et al., 2018). So,

in this early implementation stage characterized by low

public awareness and product availability, the first

spread of information (i.e., how the public comes into

touch with CCU products) is crucial. Because CCU

products and the corresponding product label are

unfamiliar to them and they cannot rely on personal

experience, laypeople might need assurance by a well-

known and trusted information source to develop trust

in a label for novel, innovative products.

The present study identified media coverage and

talks with friends and acquaintances to be the most

preferred information sources for familiarizing

respondents with the CCU product label, whereas

political actors and famous label ambassadors were

rather not evaluated as important to build trust in CCU

labels. Here, a kind of “chicken-and-egg” problem or

“double relevance” of (dis)trust gets apparent:

Previous research on consumer skepticism towards

companies’ claims about their environmental actions

has found that distrust in these claims (e.g., perceived

greenwashing) motivates laypeople to spread negative

word of mouth about the companies’ products in their

circle of friends and acquaintances (Leonidou and

Skarmeas, 2017). This means, if trust in the CCU

product label and CCU products in general fails to be

developed and mistrust is built at the early

implementation stage (e.g., by a misleading,

ambiguous information campaign that ignores

laypeople’s requirements), this might prevent a

successful market adoption of CCU products in later

stages due to dynamics of negative word of mouth.

The findings of this study should be interpreted

with caution: It should not be concluded that

parameters related to the certification process and label

design are unimportant for trust-building in the CCU

label because respondents evaluated certifying

organization and process criteria as most relevant for

their trust and distrust in a CCU product label. When

CCU products become more widely available on the

market, there might be a shift in importance: Once

people know about the products and the label, other

factors like unambiguity and comprehensibility of

presented information, argument specificity of label

claims, label familiarity, and governmental / third-

party certification may come into play since these are

important parameters influencing trust and preferences

for eco-labels (Atkinson and Rosenthal, 2014; Moon et

al., 2017; Sirieix et al., 2013).

From a perspective on trust theory and

conceptualization, the present results corroborate

findings from past research (e.g., McKnight and

Chervany, 2001; Van de Walle and Six, 2014) that trust

and distrust are in a wide array separate concepts

because the obtained factor structure for trust and

distrust conditionals represented mostly pure trust or

distrust factors. There was only one “mixed” factor

containing both, trust and distrust conditionals.

4.2 One Label for All? Or the Impact

of Individual Factors on CCU

Labels

Analyzing the impact of user factors on CCU label

perceptions, it was found that CCU label trust and

purchase intention for CCU products were (directly)

influenced by different antecedents. Whereas CCU

label trust was mainly affected by trust-related factors

(trust disposition and general trust in product labels)

and by age, the purchase intention for labeled CCU

products was increased by a more environmentally

aware behavior and a lower technical self-efficacy.

These findings partly mirror results from

(Sønderskov and Daugbjerg, 2011) on eco-label trust,

which was also found to be affected by general trust

constructs (general social and institution-based trust)

Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU Product Label

65

and to be higher in younger people, but they are not

in line with the influence of environmental awareness

and gender identified in that study. Interestingly, in

the present study environmental awareness came into

play for the purchase intention related to labeled CCU

products, which corroborates findings from past

research on attention to and preferences for eco-labels

(e.g., Thøgersen, 2000). An explanation for the

identified negative influence of technical self-

efficacy on intention to buy labeled CCU products

could be that people who feel generally more affine

to technology do not want or need to rely on a product

label for decision guidance but tend to rely rather on

their individual knowledge and experience for

product selection. This explanation attempt needs to

be investigated in future studies. Although trust

disposition and general trust in labels did not directly

influence CCU product purchase intention, there

might have been an indirect impact of these general

trust attitudes via CCU label trust, which was found

to be the biggest driver for the intention to buy CCU

products. The effect of label trust on purchase

intention mirrors previous research on eco-label

adoption (e.g., Konuk, 2018; Teisl et al., 2008).

4.3 Methodological Considerations

The present study suffers from some methodological

issues that should be addressed by future research.

One limitation is the small, young, and highly

educated sample. Though appropriate for a first

exploration of trust in a CCU label, the study should

be replicated with a census representing sample to

measure the view of the entire German population.

A further methodological consideration is the way

the relevance of trust and distrust factors for building

trust was assessed: If survey respondents are

presented with a list of predefined factors and asked

to indicate if these aspects might raise their trust, their

attention is artificially drawn to these aspects. Thus,

respondents might tend to find every aspect offered to

them important, although they might not have thought

of these factors themselves, leading to an

overestimation of trust-relevance (over-trust, Goel et

al., 2005). Therefore, a strength of the present study

is the additional investigation of impact factors on

trust using regression analysis, which revealed that

only sources informing about the CCU label

significantly affected trust in CCU labels. Future

studies should investigate if trust and distrust are

affected by similar certification-related

characteristics or whether impact factors differ.

The obtained (dis)trust factor structure was not

completely distinct, e.g., in some cases items with a

similar semantic content loaded on different factors.

Therefore, the factorial structure of trust and distrust

in CCU labels should be replicated in future studies

with a bigger and more balanced sample to more

precisely “carve out” the factors and subdimensions.

Moreover, the present research focused

exclusively on the trusting belief dimensions of

benevolence and integrity related to the CCU label

certification. Since the framework of McKnight and

Chervany (2001) also includes trusting beliefs related

to competence and predictability as factors

influencing trusting intentions, these should be

examined in future studies on CCU label trust. The

impact of these missing dimensions might explain the

significant difference between trusting beliefs and

trusting intention in the current study, assuming that

trusting intentions are a function of adding up and

weighing different dimensions of trusting beliefs.

4.4 Recommendations for a

Trust-Building CCU Product Label

Summarizing the study’s results, the following

recommendations (“Do’s” and “Don’ts”) for a trust-

building CCU product label can be derived:

What policymakers and CCU industry should do…

• Integrate the user perspective in early stages of

CCU product development and CCU label design

to achieve user-centered innovations.

• Enable consumers to make an informed purchase

decision for CCU products.

• Assign the awarding decision of the CCU label to

an independent organization.

• Make CCU label awarding criteria and time frame

transparent.

• Provide comprehensible, unambiguous, neutral,

and verifiable information on and about the CCU

label.

• Develop transparent and credible information

campaigns involving trusted information sources

such as the media to raise awareness and

familiarity of the CCU label.

What you should not do (anymore)…

• Do not solely target at the merchantability of CCU

products but include laypeople’s needs and

concerns in the development of novel products

and product labels.

• Do not try to persuade people to accept novel

technology – acceptance is a fragile good which

needs to be donated by consumers.

• Do not include user requirements only out of

moral or social justice reasons but because they

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

66

are valuable information sources for designing

targeted communication strategies and tailoring

products to consumer needs.

• Do not use famous label ambassadors as

testimonials for a CCU product label.

• Avoid misleading label claims that elicit

misconceptions and distrust.

• Avoid a label awarding by CCU industry or a

dependent organization.

From an overarching perspective, trust is only one (but

a very essential) aspect of a successful label design.

Thus, after identifying the trust-building conditions for

the CCU label development, future studies should

expand the scope to consumer requirements for

comprehensibility and preferred label design (i.e., label

wording, color scheme, design elements). This would

help label developers to gain a deeper understanding

on how to create a socially-accepted label, which raises

public awareness of CCU products, assists laypeople in

informed purchase decisions, and subsequently

supports the market adoption of CCU products.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Saskia Ziegler for research support.

This work has been funded partly by the European

Institute of Technology & Innovation (EIT) within the

EnCO2re flagship program Climate-KIC and partly by

the Cluster of Excellence “Fuel Design Center” under

Contract EXC 2186 by the German federal and state

governments.

REFERENCES

Arning, K., Offermann-van Heek, J., Linzenich, A.,

Kaetelhoen, A., Sternberg, A., Bardow, A., Ziefle, M.,

2019. Same or different? Insights on public perception

and acceptance of carbon capture and storage or

utilization in Germany. Energy Policy, 125, 235–249.

Atkinson, L., Rosenthal, S., 2014. Signaling the Green Sell:

The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument

Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer

Trust. Journal of Advertising, 43(1), 33–45.

Beier, G., 1999. Locus of control when interacting with

technology (Kontrollüberzeugungen im Umgang mit

Technik). Report Psychologie, 24, 684–693.

Bögel, P., Oltra, C., Sala, R., Lores, M., Upham, P.,

Dütschke, E., Schneider, U., Wiemann, P., 2018. The

role of attitudes in technology acceptance management:

Reflections on the case of hydrogen fuel cells in Europe.

Journal of Cleaner Production, 188, 125–135.

Brécard, D., Lucas, S., Pichot, N., Salladarré, F., 2012. Con-

Consumer preferences for eco, health and fair trade

labels. An application to seafood product in France.

Journal of Agricultural & Food Industrial Organization,

10(1).

Emberger-Klein, A., Menrad, K., 2018. The effect of

information provision on supermarket consumers’ use of

and preferences for carbon labels in Germany. Journal of

Cleaner Production, 172, 253–263.

European Commission, 2013. Attitudes of Europeans

towards building the single market for green products.

Flash Eurobarometer 367. Retrieved February 8, 2019,

http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/flash

/fl_367_en.pdf

European Commission, 2008. Attitudes of European citizens

towards the environment. Special Eurobarometer

295/Wave 68.2. Retrieved February 8, 2019, from

http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archi

ves/ebs/ebs_295_en.pdf

Feucht, Y., Zander, K., 2018. Consumers’ preferences for

carbon labels and the underlying reasoning. A mixed

methods approach in 6 European countries. Journal of

Cleaner Production, 178, 740–748.

Field, A., 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.).

London: Sage.

Goel, S., Bell, G. G., Pierce, J. L., 2005. The perils of

Pollyanna: Development of the over-trust construct.

Journal of Business Ethics, 58(1-3), 203-218.

Hair, J. F., 2011. Multivariate data analysis: an overview. In

Lovric, M. (Ed.), International encyclopedia of statistical

science. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Huijts, N. M. A., Molin, E. J. E., Steg, L., 2012.

Psychological factors influencing sustainable energy

technology acceptance: A review-based comprehensive

framework. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews,

16(1), 525–531.

Jones, C. R., Olfe-Kräutlein, B., Naims, H., Armstrong, K.,

2017. The Social Acceptance of Carbon Dioxide

Utilisation: A Review and Research Agenda. Frontiers

in Energy Research, 5:11.

Konuk, F. A., 2018. The role of store image, perceived

quality, trust and perceived value in predicting

consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private

label food. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,

43, 304–310.

Leonidou, C. N., Skarmeas, D, 2017. Gray Shades of Green:

Causes and Consequences of Green Skepticism. Journal

of Business Ethics, 144(2), 401–415.

McKnight, D. H., Chervany, N. L., 2001. Trust and Distrust

Definitions: One Bite at a Time. In Falcone, R., Singh,

M., Tan, Y.-H. (Eds.), Trust in Cyber-societies (Lecture

Notes in Computer Science Vol. 2246, pp. 27–54).

Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., Kacmar, C., 2002.

Developing and validating trust measures for e-

commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems

Research, 13(3), 334–359.

Moon, S.-J., Costello, J. P., Koo, D.-M., 2017. The impact of

consumer confusion from eco-labels on negative WOM,

distrust, and dissatisfaction. International Journal of

Advertising, 36(2), 246–271.

Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU Product Label

67

Moussa, S., Touzani, M., 2008. The perceived credibility of

quality labels: a scale validation with refinement. In-

ternational Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(5), 526–

533.

Offermann-van Heek, J., Arning, K., Linzenich, A., Ziefle,

M., 2018. Trust and Distrust in Carbon Capture and

Utilization Industry as Relevant Factors for the

Acceptance of Carbon-Based Products. Frontiers in

Energy Research, 6:73.

Olfe-Kräutlein, B., Naims, H., Bruhn, T., Lorente Lafuente,

A. M., 2016. CO

2

as an Asset – Challenges and Potential

for Society. Potsdam: IASS. Retrieved February 8, 2019,

from http://publications.iass-

potsdam.de/pubman/item/escidoc:2793988:3/componen

t/escidoc:2793989/IASS_Study_2793988.pdf

Sirieix, L., Delanchy, M., Remaud, H., Zepeda, L., Gurviez,

P., 2013. Consumers’ perceptions of individual and

combined sustainable food labels: a UK pilot

investigation. International Journal of Consumer

Studies, 37(2), 143–151.

Sønderskov, K. M., Daugbjerg, C., 2011. The state and

consumer confidence in eco-labeling: organic labeling in

Denmark, Sweden, The United Kingdom and The United

States. Agriculture and Human Values, 28(4), 507–517.

Teisl, M. F., Rubin, J., Noblet, C. L., 2008. Non-dirty

dancing? Interactions between eco-labels and consumers.

Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(2), 140–159.

Thøgersen, J., 2000. Psychological Determinants of Paying

Attention to Eco-Labels in Purchase Decisions: Model

Development and Multinational Validation. Journal of

Consumer Policy, 23(3), 285–313.

Thøgersen, J., Haugaard, P., Olesen, A., 2010. Consumer

responses to ecolabels. European Journal of Marketing,

44(11/12), 1787–1810.

UNEP, 2017. The Emissions Gap Report 2017. Nairobi:

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Retrieved February 8, 2019, from https://www

.unenvironment.org/resources/emissions-gap-report

Upham, P., Dendler, L., Bleda, M., 2011. Carbon labelling of

grocery products: public perceptions and potential

emissions reductions. Journal of Cleaner Production,

19(4), 348–355.

Van de Walle, S., Six, F., 2014. Trust and Distrust as Distinct

Concepts: Why Studying Distrust in Institutions is

Important. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis:

Research and Practice, 16(2), 158–174.

Van Heek, J., Arning, K., Ziefle, M., 2017. Differences

between Laypersons and Experts in Perceptions and

Acceptance of CO

2

-utilization for Plastics Production.

Energy Procedia, 114, 7212–7223.

Von der Assen, N., Bardow, A., 2014. Life cycle assessment

of polyols for polyurethane production using CO

2

as

feedstock: insights from an industrial case study. Green

Chemistry, 16, 3272–3280.

Waechter, S., Sütterlin, B., Siegrist, M., 2015. The

misleading effect of energy efficiency information on

perceived energy friendliness of electric goods. Journal

of Cleaner Production, 93, 193–202.

Wippermann, C., Calmbach, M., Kleinhückelkotten, S.,

2008. Umweltbewusstsein in Deutschland 2008.

Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage.

Berlin: Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und

Reaktorsicherheit (BMU). Retrieved February 8, 2019,

from

https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/me

dien/publikation/long/3678.pdf

Zimmermann, A. W., Schomäcker, R., 2017. Assessing

Early-Stage CO

2

utilization Technologies—Comparing

Apples and Oranges? Energy Technology, 5(6), 850–

860.

APPENDIX

Table A.1: Items used for construct measurement.

Constructs

Items

Environmentally aware behavior

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78)

Item sources:

European Commission (2008);

Wippermann et al. (2008)

When buying household appliances, I pay attention to a low energy consumption.

When buying textiles, I make sure that they do not contain any harmful substances.

I purposefully buy products that cause as little harm as possible to the environment both during their

production and use.

I pay attention that the devices and products I buy are durable and repairable.

I purposefully buy regionally produced fruits and vegetables.

I try to avoid waste caused by unnecessary packaging, unnecessary plastic bags, etc.

Technical self-efficacy

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90)

Item source:

Beier (1999)

I really enjoy solving technical problems.

I can solve many of the technical problems I am confronted with on my own.

Because I could cope well with technical problems so far, I am optimistic about future technical

problems.

I feel so helpless when interacting with technical devices that I rather keep my hands off them.

Self-reported knowledge about

CCU*

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92)

I feel well informed about the topic of CCU.

I feel well informed about CO

2

capture.

I feel well informed about the utilization of CO

2

as feedstock.

I feel well informed about the CCU product spectrum.

General trust in labels*

I completely trust in product labels.

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

68

Table A.1: Items used for construct measurement(cont.).

Trust in the CCU product label*

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81)

I would trust the CCU product label. (trusting intention)

I would use products with a CCU label without any concerns. (trusting intention)

I believe that the idea of a CCU product label is well-intentioned with regard to consumer interests.

(trusting belief – benevolence)

I believe that the CCU product label shall inform consumers. (trusting belief – benevolence)

I trust that the information displayed on the label is true. (trusting belief – integrity)

Purchase intention for labeled CCU

products*

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87)

I would prefer products with the CCU label to conventional products.

The CCU product label would convince me to buy novel / unfamiliar products.

I would actively search for products with the CCU label.

While shopping, I would purposefully look out for the CCU product label.

I would rather like to use products with the CCU label compared to conventional alternatives.

*Items were specifically developed for the topic of CCU labels and validated in pre-studies. Item development was based on results from

an interview pre-study and on research literature (for CCU label trust: Moussa and Touzani, 2008).

Table A.2: Rotated factor loadings of (dis)trust conditionals for a CCU product label on the extracted factors.

Trust /

Distrust

(T/D)

I would (dis)trust a CCU label if...

1

Unknown,

private

certifying

organization

2

Transparent,

independent

certification

process

3

Infor-

mation

sources

4

Provided

label

information

5

Unusual

label

design

D

the product manufacturers awarded the label.

.819

D

it was not awarded by an independent organization.

.795

D

a private organization awarded the label.

.663

D

there was no information about the certifying

organization which awards the label.

.570

D

I did not know the certifying organization.

.520

T

the criteria and conditions for awarding the label

process were transparent to me.

.799

T

it informed me about figures for the CO

2

footprint

compared to conventional products.

.734

T

the guidelines and timeframe of the product

controls were transparent to me.

.604

T

the certifying organization was independent.

.555

T

politicians drew attention to the label and

recommended it.

.808

T

it was disseminated and explained by the media

(newspapers, TV, radio).

.717

T

it was represented by a famous label ambassador.

.689

T

my friends and acquaintances told me about it.

.654

D

there was no reference to additional information

(weblink or QR code).

.797

D

it contained only little information.

.614

T

information about the certifying organization (e.g.,

the organization’s headquarters) was available.

.534

D

it had an unusual design compared to other labels.

.854

D

it had an unusual shape compared to other labels.

.764

Bartlett’s test of sphericity p < 0.001, KMO = .775

Items that did not load on the 5 identified factors with a factor loading > .512 were excluded.

Identifying the “Do’s” and “Don’ts” for a Trust-Building CCU Product Label

69