Cadenza: The Evolution of a Digital Music Education Tool

Rena Upitis

1

and Philip C. Abrami

2

1

Faculty of Education, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

2

Centre for the Study of Learning and Performance, Concordia University, Montreal, Québec, Canada

Keywords: Music, Self-regulation, Technology Transfer.

Abstract: This paper describes the evolution of Cadenza, a digital music tool designed to inspire and assist students with

practising between music lessons. Cadenza was developed using an evidence-based research and design

model, supported by funding for both the research and software design. The focus of the present case study is

on how Cadenza has continued to thrive after the research funding period ended, through a community-based

not-for-profit organizational structure housed within the auspices of the host research institution. In an era

where technology transfer has become a goal for many post-secondary institutions, this case study illuminates

both the advantages and pitfalls of creating a start-up enterprise under the umbrella of an established university.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital tools for music teaching and learning can

enrich and even transform students’ musical worlds.

There is extraordinary potential for music technology

to engage students in their musical practice, link them

to their teachers and musician peers, and help them

develop the kinds of habits they need to make music

for the duration of their lives (Gouzouasis and Bakan,

2011; Ruthmann and Mantie, 2017). Further, digital

tools and online communities have the potential to

help teachers form collaborative professional

networks (Burnard, 2007; Savage, 2017) which is of

considerable importance in a profession that is largely

unregulated and has been identified as being marked

by professional isolation (Feldman, 2010).

But using digital tools, especially where the aim

is to develop self-regulated musicians, is not without

challenges. The tools themselves need to be powerful

and appealing in a sustained way—they need to do

much more than engage the students initially, only to

be dropped for the next tool or app that comes along.

The teachers using the tools also need to have

technological and pedagogical savvy, or at least the

willingness to learn, in order for such tools to be

effective. And the tools also need to continue to

evolve and develop, in a sustained manner, in order

to continually improve the teaching and learning

environments in which they are used.

With these considerations in mind, in this paper

we describe a digital tool that was expressly designed

for the independent music studio. The evolution of the

development of this tool, based on an evidence-based

research approach and the self-regulation learning

theory, is also described. Next, we discuss how this

iterative evolution, based on research findings, was

transitioned to a new university-based organizational

structure, allowing for the continual evolution of the

technologies once the formal funding for research and

development ended.

2 LITERATURE

In many countries, world-wide, where the Western

musical canon prevails, millions of young people take

weekly music lessons from independent or studio

music teachers, often in addition to their school music

instruction. In Canada alone, it is estimated that over

2 million students are involved in this particular form

of music education annually (Upitis and Smithrim,

2002). Increasingly, these students are using digital

music technologies to support their music teaching

and learning, some of which have been designed with

the explicit aim of developing independent self-

regulating lifelong musicians (Upitis et al., 2013).

2.1 Developing Self-regulated Learners

A vast array of studies has demonstrated that learning

is more enduring and effective when students take

control over their learning through processes of self-

Upitis, R. and Abrami, P.

Cadenza: The Evolution of a Digital Music Education Tool.

DOI: 10.5220/0007704201610168

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 161-168

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

161

regulation (Dignath et al., 2008; Zimmerman, 2011).

Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning model defines

self-regulated learning (SRL) as an incremental

process, where self-generated thoughts, feelings, and

actions are planned and adapted to achieve personal

learning goals. At the beginning, novice learners

require a considerable amount of scaffolding and

social support to emulate expert learners. Over time,

learners develop forms of scaffolded self-control, and

ultimately, self-regulation. Zimmerman (2011)

claimed that fully self-regulated learners continually

engage in an iterative three-phase cyclical process

comprised of forethought, performance/volitional

control, and self-reflection. These phases are

interactive and comprise a wide array of cognitive,

social, and motivational variables.

2.1.1 Forethought

The self-regulatory cycle begins with the forethought

phase (Zimmerman, 2011), which involves task

analysis and self-motivational beliefs. Goal setting

and strategic planning are part of task analysis, while

self-motivational beliefs encompass self-efficacy

beliefs, expectations in terms of outcomes, and the

intrinsic value placed on the learning. Goal setting

and strategic planning often take place in music

lessons with the teacher’s guidance (McPherson et al.,

2012).

2.1.2 Performance

Performance/volitional control refers to the activities

that learners undertake to describe and reach their

goals (Zimmerman, 2011). These processes might

include self-instruction, imagery, attention focusing,

and various specific task strategies to help ensure that

music practice sessions, between lessons, are efficient

and effective.

2.1.3 Self-reflection

In the third phase, learners engage in a process of self-

reflection, made up of self-judgment and self-reaction

(Zimmerman, 2011). Self-judgment involves an

evaluation of the learning activities and causal

attribution, where learners ascribe reasons for their

successes or failures, as well as factors that they can

address in the next phase of their learning

(McPherson and Renwick, 2011). The process of self-

reaction includes affective responses to the learning,

which can be adaptive or otherwise, thus influencing

the student’s development, both as a musician and as

a self-regulated learner.

2.2 Self-regulation, Music Learning,

and Digital Tools

Intense commitment is required to learn an

instrument, and it can be extraordinarily difficult to

sustain such commitment over extended periods of

time. Self-regulation holds promise as a way of

ensuring that learners develop the processes persist

with music study over many years (McPherson et al.,

2012; Varela et al., 2016).

Self-regulation is of particular importance during

the time between music lessons. While the lesson

setting consists primarily of the teacher responding to

and directing the singing or playing of the student, the

practice setting involves the student managing and

responding to his or her own singing or playing.

Students who become long-term and independent

musicians do so as a result of developing effective

habits of self-regulation (McPherson and

Zimmerman, 2011) including deliberate and effective

practice strategies (Hallam et al., 2018). Deliberate

practising involves the identification of goals,

receiving meaningful feedback through a supportive

social network, and having opportunities for mindful

repetition (Hallam et al., 2018). This kind of

deliberate practising does not come easily for many

students, and teachers use a variety of methods to

support their students between lessons (Pike, 2017;

Upitis et al., 2015).

Further, as the student implements what has been

learned at the lesson, he or she must be able to assess

whether the practising is leading to the desired

outcomes (Pike, 2017; Hallam et al., 2018). This type

of critical reflection can be difficult, as students are

required to simultaneously produce sounds and

reflect on the sounds that they produce.

Consequently, students may rely on parental

oversight, along with practice aids developed by their

teachers (Upitis et al., 2013; Upitis et al., 2015).

Students may also use digital resources to ensure that

their practice sessions are enjoyable and productive

(Partii, 2014; Savage, 2017).

2.2.1 Cadenza

Cadenza is a web-based practice tool designed on the

model of self-regulated learning. It was designed to

motivate and guide students to take responsibility for

their practising and overall music learning. In

accordance with self-regulated learning theory,

Cadenza provides the scaffolding required for

students to become self-regulated musicians by

providing features that support forethought, volitional

control, and self-reflection—the three pillars that

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

162

mark the self-regulated learning cycle (Zimmerman,

2011). There is a teacher version of Cadenza as well,

which enables teachers to streamline their record-

keeping, by quickly accessing information on

particular students or locating past lessons. The

teacher can also create group lessons, so that tasks

that are common to several students can be easily

shared, without needing to re-invent or re-type those

common tasks.

Students are encouraged to set goals, with the

guidance of their teacher(s), and during the lesson, the

teacher records the strategies that students can use to

achieve those goals. These strategies are contained

both in the task descriptions as well as in a nuanced

check-list feature, where teachers and students

together negotiate the volitional stage of their

learning. Using this sophisticated check-list feature,

the teacher can specify, for example, the total number

of repetitions for a given task, the number of correct

repetitions, or the length of time to devote to a task

for each practice session. The student then refers to

the lesson plan during the practice sessions, recalling

the directions given by the teacher during the lesson.

Cadenza tracks targets and goals as the week

progresses, and the teacher can see student progress

and check on particular aspects of practice sessions

when notified by the student.

Figure 1: Cadenza Lesson Student View.

Students and teachers can create, archive, and

display work by writing text, or uploading text, audio,

video, links, and images on either the teacher or

student version of Cadenza. Finally, students are

invited to reflect on their work to assist them in

planning for the next learning cycle. The reflection

features also enable teachers to comment on student

work in dynamic ways. One of the sharing features is

a video annotation tool, where students can upload a

sample of their playing and receive feedback from

their teacher before the following lesson. Online

teaching materials support teachers using Cadenza,

and workshops and webinars are conducted regularly

to help teachers use Cadenza effectively in their

studios. Cadenza also supports communication

between teachers and students during the week, so

that teachers are aware of the work that students have

completed between lessons, and students can seek

help as required.

2.2.2 Developing Cadenza

Cadenza is one of four digital music tools developed

by the Music Tool Suite project, a multi-institutional

partnership that was first established in 2010. The

partnership was initially comprised of a Canadian

team of researchers, studio teachers, curriculum

developers, and software designers from Queen’s

University, the Centre for the Study of Learning and

Performance (CSLP) at Concordia University, and

The Royal Conservatory of Music (until February

2017). In 2017 two new institutions joined the

partnership, the Canadian Coalition for Music

Education, a national advocacy and education group,

as well as the UK based Curious Piano Teachers, an

online professional development organization

supporting piano pedagogy.

Cadenza was created over many years using an

evidence-based approach to software design and

development, an approach that was consonant with

our university-based project. Since the development

of Cadenza was supported by several substantial

research grants, including a Canadian Social Sciences

and Humanities Research Council Partnership Grant,

the development of Cadenza and other related tools

benefited from considerable research in its evolution.

This meant that the research and development took

place in a more measured way than the fast-paced

development that characterizes the protocol of

continuous software engineering that takes place

outside of the academy (Avila et al., 2017; Fitzgerald

and Stol, 2017). However, in 2018, an outside

developer was also hired to continue development of

Cadenza, leading to the most recent release (V. 3) in

October of 2018, and thus, Cadenza, while initially

developed using an evidence-based university led

research model, is now evolving through an agile

industry approach as it transitions from its research

base to a not-for-profit organizational structure.

Cadenza was first released in April 2016 and was

made available without charge. Another tool in the

Music Tool Suite is Notemaker, an iOS app first

released in December 2015. It is an effective tool for

making real-time comments on video and audio

recordings, sharing the same type of functionality as

the video annotator in Cadenza. A third tool in the

Cadenza: The Evolution of a Digital Music Education Tool

163

suite, DREAM (Digital Resource Exchange About

Music) was initially released in September 2014 and

was designed to provide teachers easy access to

digital resources related to music education. DREAM

is no longer supported, as the project does not have

the resources to continue to curate the site. Finally,

iSCORE, a web-based practice and communication

tool, was released in 2012 and re-released in 2013. It

continues to available in both English and French and

has a limited number of users in Canada and Europe.

All of these tools are supported by instructional

videos to help teachers, parents, and students

implement them effectively at home and in the music

studio. Videos can be accessed through our website

(www.musictoolsuite.ca) or on our YouTube

channel.

2.3 Post-development: What Next?

It is not uncommon for academic research projects to

wind down completely when the funding period ends.

As a result, a number of universities have recently

developed structures to increase the likelihood of the

commercialization of research activity through the

spinoff of new companies (Fitzgerald and Stol, 2017;

O’Shea et al., 2007). The host institution for the

Music Tool Suite project, Queen’s University, is one

of many universities that is now learning to adopt this

approach, devoting both financial and human

resources to knowledge mobilization and technology

transfer, as well as embedding supporting structures

into the university itself. The central purpose of this

paper is to describe the initial phases of the post-

development journey of the Cadenza tool.

3 METHODOLOGY

A case study methodology was used to characterize

the evolution of Cadenza from a university research

project to a social entrepreneurship start-up

community organization (Yin, 2017). The case study

was bounded by a 20-month time frame, beginning in

March of 2017. The organizations involved included

the founding universities (Concordia and Queen’s),

the newly acquired industry developer (Troon

Technologies), and the two new partnering

organizations (Canadian Coalition for Music

Education and Curious Piano Teachers). The research

was carried out in accordance with the Canadian Tri-

Council Policy Statement governing research with

human participants (Canadian Tri-Council Policy

Statement 2, 2010). Data sources included interviews

with key informants, reflective field notes of the first

author, meeting notes involving the various partners

and staff involved in the Cadenza transition, and

electronic surveys of teachers using Cadenza. Data

were coded according to standard protocols for

analysing qualitative data (Yin, 2017), and results

were grouped into six overarching themes, as

described in the section that follows.

4 RESULTS

The transition from a university research-based

project to a self-sustaining business enterprise has

resulted in a number of challenges as well as new

opportunities that were not previously available to the

project team. These challenges and opportunities are

delineated below under six major categories,

including a set of false starts which ultimately led to

the structure that has been adapted for Cadenza.

These include (a) identifying a suitable structure, (b)

legal documentation and operational logistics, (c)

finding an industry partner, (d) hiring a Project

Manager within the university structure, (e)

negotiating with senior university administration, and

(f) marketing and communications.

4.1 Organizational Structure

The first conceptual task in moving to a self-

sustaining enterprise was the identification of an

organizational and governance structure. To this end,

several avenues and approaches were explored

without success. These included but were not limited

to: (a) making pitches to start-up local companies, (b)

attempting to merge with another company that

created digital tools for music education, (c)

partnering with software and book publishers, (d)

identifying higher education music partners, such as

conservatories, to mobilize the software, (e) licensing

Cadenza to organizations in China (e.g., the Shanghai

Symphony Orchestra, based on an initiative

spearheaded and financed by the senior

administration of Concordia University), (f) creating

an open source structure, and (g) forming a new

company.

For various reasons, these routes were abandoned,

as it became clear after meetings and negotiations that

the fit was not ideal for promoting Cadenza.

Ultimately, at the suggestion of the Office of

Innovation, the founding partners along with the two

new partners determined that creating an open

community structure, housed as a not-for-profit

within the university, was the most likely avenue to

success. By housing what is essentially a small

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

164

business within the university, located at the Faculty

of Education where the research project was also

hosted, the Cadenza Community Project could take

advantage of university resources at a time when the

university was also interested in promoting this kind

of knowledge mobilization—a form of technology

transfer involving a type of social entrepreneurship.

4.2 Legal Documentation

Once the governance structure was determined,

namely, a self-governing Steering Committee made

up of the founding institutions as well as community

partners, the process of developing the legal

documentation began. Here we were aided by being

part of a university system, as the host university took

on the task of creating both the governance structure

as well as the contributor agreements, necessary to

acknowledge the past contributors of Cadenza and to

release any future claims on the tool. In addition, a

Research Amendment agreement needed to be

formulated between the two universities, in order to

move forward from the research-based structure to

the independent Cadenza Community Project. These

documents were first drafted in May of 2017. At the

time of writing the present paper, the documents had

not yet been signed by the two institutions but were

in the final stages of negotiation. Legal

documentation not only considered the issues

associated with intellectual property, but also any

future licensing arrangements that might be

undertaken, outside of the scope of the Community

Project itself.

In addition to the development of the legal

documents, there were a number of logistical issues

encountered on the financial side in terms of a

revenue-generating enterprise within the University

that was not part of an existing structure (e.g., tuition

for courses). Several issues were encountered and

resolved, including the integration of a payment

system for Cadenza that would involve credit card

payments, the creation of a tracking system for

banking, and the negotiation of a tax on revenue. The

University’s policy of a 40% tax on external revenue

was re-negotiated to 4% for the purposes of the

Cadenza Community Project.

4.3 Industry Partner

Early in the evolution of the Cadenza Community

Project, it became crucial to identify a new software

developer, outside of the university context. We were

aided by the Director of Partnerships and Innovation

at Queen’s University in identifying such a partner.

Troon Technologies began working on Cadenza in

April 2018, and delivered two new versions, the most

recent of which was released in October 2018. The

new versions feature a contemporary homepage and

login, replacing the functional but less appealing

university design (see Figure 2), as well as several

new types of functionality, including a feature to

allow the creation of group lessons and the addition

of the video annotation tool to the teacher view. These

changes, among others, have been embraced by our

student and teacher users.

Figure 2: Cadenza homepage.

The research literature suggests that industry

software development often from a lack of integration

of planning, development and implementation

(Fitzgerald and Stol, 2017). Researchers claim that

what can be a lack of integration in industry is further

complicated by problems in coordinating testing

timing of releases. These types of problems were not

encountered in our transition to Troon Technologies,

as we have not experienced any discontinuities

between development and deployment. That said,

there were several striking differences between

working with an industry partner and a university

partner in software development. For example, in our

experience, the university-based software

development excelled at the integration of planning,

development, and integration, but with the

consequence that releases were infrequent, an often a

year apart. Also, the ways in which the two

organizations approached needs assessment and

Cadenza: The Evolution of a Digital Music Education Tool

165

design, as well as debugging the penultimate versions

prior to release differed considerably. That said, the

combination of the two approaches has led to a

version of Cadenza that our users have embraced

wholeheartedly, as indicated by post-release survey

responses, the growth of new users, and the decrease

in user queries regarding technical and pedagogical

concerns.

4.4 Project Manager

The identification of a suitable Project Manager was

a relatively easy task, as one of the teacher advisors

who had been part of the Music Tool Suite since its

inception was both capable and willing to take on the

task. She was an ideal candidate, as she was already

extremely familiar with the tool, having helped guide

its development, and her large music studio practice

made her an ideal person to interface with the users

of Cadenza. In addition, as a music studio teacher, she

had considerable expertise in running a small

business, and this background has been essential to

the start-up of the Cadenza Community Project. At

the time of writing, the Project Manager had just

finished her fourth month in the position.

It proved to be more difficult to hire such a person

within the university staffing structure. Our Project

Manager, in fact, has assumed the duties of an

Executive Director, and would be named as such were

this organization to be housed outside of the confines

of the University. However, the moniker of Executive

Director has specialized meaning within the

University and could not be used in the present

situation. It remains to be seen whether the title of

Project Manager is properly understood outside of the

university context.

4.5 Senior University Administration

Several layers of university administration were

involved in the establishment of the Cadenza

Community Project. At the central level of

administration, there was both support and

encouragement in establishing the organization.

Senior staff from the Office of the Vice-Principal

(Research) devoted countless hours consulting with

the research team in order to make the transition. In

addition, the Dean of the Faculty of Education made

many tangible commitments to the project, including

the provision of office space as well as agreeing to

underwrite the project until August 31, 2021. This

agreement gave the Cadenza Community Project a

three-year window to show a profit and to begin to

create a reserve fund.

4.6 Marketing and Communications

An effective marketing plan will be essential to the

ultimate fate of the Cadenza Community Project. We

were able to identify an independent marketer to help

with the initial phases of the Cadenza Community

Project. The first six-week campaign was successful

by industry standards, as measured by organic growth

in terms of Facebook posts, the list of teachers

subscribing to the Cadenza mailing list, and the open

rates and click rates for newsletter items. In terms of

the latter, the open rates for our newsletters averaged

40% (industry standard 15.8%) and click rates

averaged 3.5% (industry standard 1.5%).

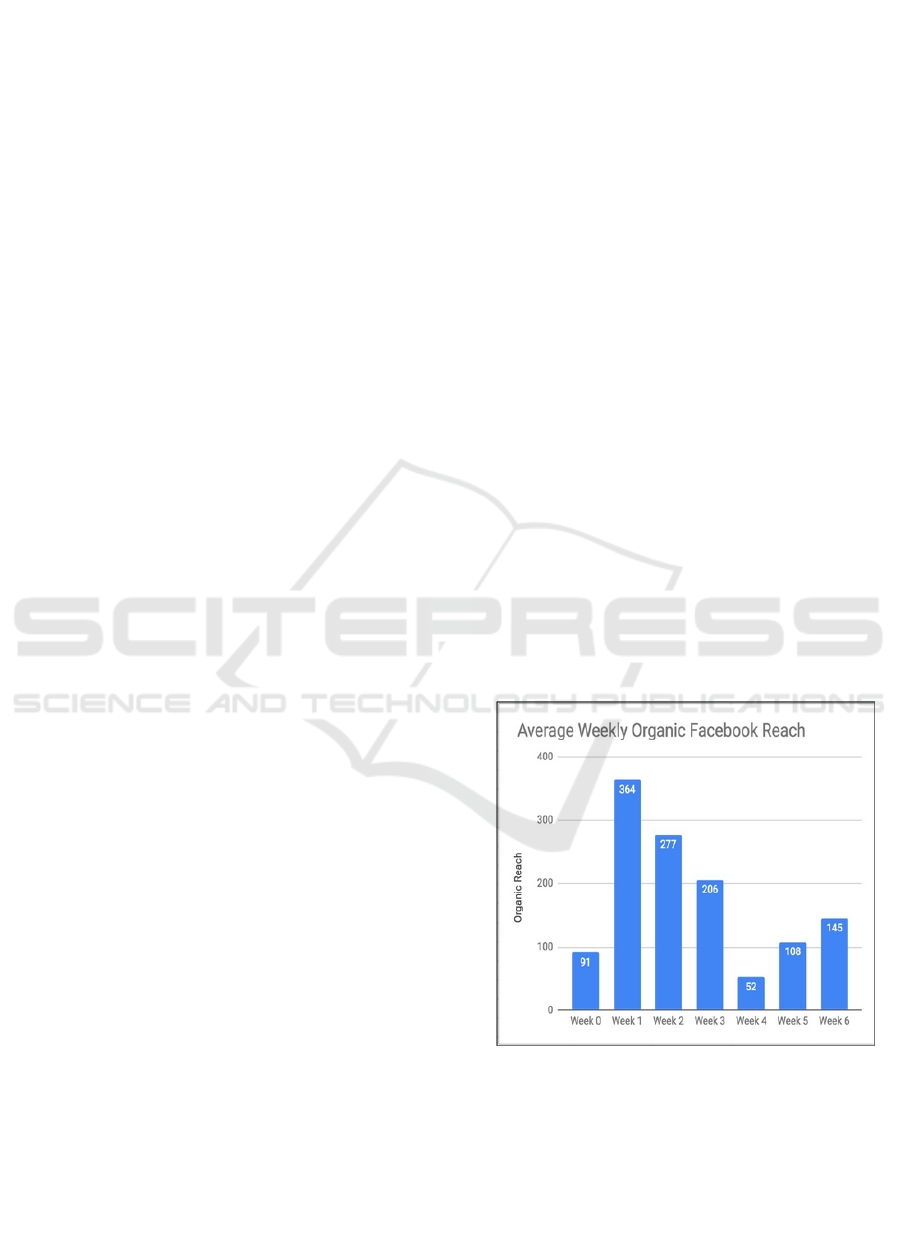

The organic Facebook reach is depicted in Figure

3. Analysis of Facebook users showed that audience

members who engaged with two or more posts a week

were most engaged by those posts that promised to

teach them something about their profession—music

education—for free. So, for example, posts about

how to set up a lesson using Cadenza were

particularly effective. Looking deeper at the posts, the

posts that showed images of the tool, used “how to”

language, and explained how the tool would help

teachers and students, resulted in the highest

engagement rates. The analysis of the campaign also

showed that diversity in post topics was crucial, as

well as the approach of addressing “pain points,” that

is, aspects of the profession that teachers found to be

particularly challenging.

Figure 3: Facebook Reach.

From the analysis of the first six-week marketing

campaign, it is predicted that the growth will be slow,

but consistent, with 300 teachers joining in the next

academic year on a base of 3,500 users. This growth

should be more than ample in terms of meeting our

revenue projections, where we require 50 subscribers

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

166

in the first year for a break-even scenario. As with the

development of the Cadenza tool itself, we will

monitor the effectiveness of the marketing campaign

and make iterative adjustments accordingly.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The initial challenges involved in moving Cadenza

from a university research-based setting to a stand-

alone enterprise have been considerable. The

difficulties have been compounded by being the first

social entrepreneurship project in the Faculty of

Education: we expect that, if we are successful, future

groups will encounter fewer logistical difficulties,

given that the way will have been paved, at least in

part, by the Cadenza Community Project. There are

also the challenges associated with any start-up,

namely, learning to operate so that the enterprise

breaks even and continues to evolve so that further

developments to the initial products can be made and

new products can be developed. Given that at the time

of writing the Community Project was still in its

infancy, it is difficult to say whether the project will

take root and flourish. However, even the

documentation to date is of academic interest at the

very least: case studies such as this one can be fruitful

for business schools interested in analysing this

evolution of university-based entrepreneurship

enterprises. Ultimately, in the spirit of honouring the

research that went into the development of Cadenza,

attempting to make this new structure work feels like

a moral imperative, to honour not only the research

investment, but also, the dedication of the students,

parents, and teachers who invested so much in the

development of Cadenza.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the music teachers who took part

in the research that was undertaken to develop

Cadenza and the other tools in the Music Tool Suite,

as well as the team members of the Music Tool Suite

and the Cadenza Community Project. This work was

supported by a partnership grant from the Social

Sciences and Humanities Research Council of

Canada (SSHRC), the Canada Foundation for

Innovation (CFI), the Centre for the Study of

Learning and Performance at Concordia University,

and Queen’s University. Special thanks to the Office

of Partnerships and Innovation at Queen’s University.

REFERENCES

Avila, L. V., Filho, W. L., Brandii, L., Macgregor, C. J.,

Molthan-Hill, P., Ozuyar, P., Moreira, R. M., 2017.

Barriers to innovation and sustainability at universities

around the world. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol.

164, No. 15, pp. 1268–1278.

Burnard, P., 2007. Reframing Creativity and Technology:

Promoting Pedagogic Change in Music Education.

Journal of Music Technology and Education, Vol. 1,

No. 1, pp. 196–206.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences

and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social

Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada,

Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for

Research Involving Humans (TCPS2), December 2010.

Dignath, C. et al., 2008. How Can Primary School Students

Learn Self-Regulated Learning Strategies Most

Effectively? A Meta-Analysis on Self-Regulation

Training Programmes. Educational Research Review,

Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 101–129.

Feldman, S., 2010. RCM: A Quantitative Investigation of

Teachers Associated with the RCM Exam Process.

Susan Feldman and Associates, Toronto, CA.

Fitzgerald, B., Stol, K. J., 2017. Continuous software

engineering: A roadmap and agenda. Journal of

Systems and Software, Vol. 123, pp. 176–189.

Gouzouasis, P., Bakan, D., 2011. The Future of Music

Making and Music Education in a Transformative

Digital World. UNESCO Observatory E-Journal. Vol.

2, No. 2. Retrieved from http://education.unimelb.

edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1106229/012_GO

UZOUASIS.pdf

Hallam, S., Papageorgi, I., Varvariagou, M., Creech, A.,

2018. Relationships between practice, motivation, and

examination outcomes. Psychology of Music,

doi.org/10.1177/0305735618816168

McPherson, G. E., Davidson, J. W., Faulkner, R., 2012.

Music in Our Lives: Redefining Musical Development,

Ability and Identity, Oxford University Press. Oxford,

UK.

McPherson, G. E., Renwick, J. M., 2011. Self-regulation

and mastery of musical skills, in Handbook of Self-

Regulation of Learning and Performance, eds. B. J.

Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk, Routledge, New York,

pp. 327–347.

O’Shea, R. P., Allen, T. J., Morse, K. P., O’Gorman, C.,

Roche, F., 2007. Delineating the anatomy of an

entreprenurial university: The Massachusetts Institute

of Technology experience. R and D Management, Vol.

33, No. 1, pp. 1–16.

Partii, H., 2014. Cosmopolitan musicianship under

construction: digital musicians illuminating emerging

values in music education. International Journal of

Music Education, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 3–18.

Pike, P., 2017. Self-regulation of teenaged pianists during

at-home practice. Psychology of Music, Vol. 45, No. 5,

pp. 739–751.

Ruthmann, A., Mantie, R., 2017. Oxford Handbook of

Technology and Music Education, Oxford, New York.

Cadenza: The Evolution of a Digital Music Education Tool

167

Savage, J., 2017. Where Might We Be Going? In Oxford

Handbook of Technology and Music Education, eds. S.

A. Ruthmann and R. Mantie, Oxford, New York, pp.

149–156.

Upitis, R., Varela, W., Abrami, P. C., 2013. Enriching the

Time Between Music Lessons with a Digital Learning

Portfolio. Canadian Music Educator, Vol. 54, No. 4,

pp. 22–28.

Upitis, R., Varela, W., Abrami, P. C., 2015. Exploring the

Studio Music Practices of Independent Music Teachers.

Canadian Music Educator, Vol. 56, No. 4, pp. 4–12.

Upitis, R., Smithrim, K., 2002. Learning Through the

Arts

TM

: National Assessment—A Report on Year 2

(2000–2001). The Royal Conservatory of Music,

Toronto, CA.

Varela, W. Abrami, P. C., Upitis, R., 2016. Self-Regulation

and Music Learning: A Systematic Review. Psychology

of Music, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 55–74.

Yin, R. K., 2017. Case Study Research and Applications:

Design and Methods. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Zimmerman, B. J., 2011. Motivational Sources and

Outcomes of Self-Regulated Learning and

Performance, in Handbook for Self-Regulation of

Learning and Performance, eds. B. J. Zimmerman and

D. H. Schunk, Routledge. New York, USA, pp. 49–64.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

168