The Problem with Teaching Defence against the Dark Arts: A Review

of Game-based Learning Applications and Serious Games for Cyber

Security Education

Rene Roepke and Ulrik Schroeder

Learning Technologies Research Group, RWTH Aachen University, Ahornstrasse 55, 52074 Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Cybersecurity Education, Serious Games, Game-based Learning, End-users and Risk Awareness.

Abstract: When it comes to game-based approaches for cyber security education for end-users, similarities can be

drawn to the problem with teaching Defence against the Dark Arts at Hogwarts. While teachers do not last

due to the position’s curse, game-based approaches in cyber security education for end-users often do not

survive the prototype phase and hence, they are not available to the public. In this paper, we review game-

based learning applications and serious games for cyber security education for end-users to respond to two

hypotheses. First, we expect that not many games for end-users without prior knowledge and skills in

Computer Science (CS) are available. Next, we hypothesize that available games do not teach sustainable

knowledge or skills in CS to properly qualify end-users. For review, we use a two-fold approach including a

systematic literature review and a product search. As a result, we falsified the first hypothesis and found

indicators verifying the second. Future work includes a closer look on available games with respect to game

mechanisms, technologies and design principles.

1 INTRODUCTION

Every year, a new teacher attempts to teach Defence

against the Dark Arts at Hogwarts School of

Witchcraft and Wizardry, but due to the position’s

curse they last only one year before leaving and

never returning. It seems like there is a lack of good

teachers for this subject, although many try to

conquer it. When it comes to educational approaches

in cyber security, similarities can be drawn.

In the past 15 years, various game prototypes for

cyber security education were developed and

evaluated. As either game-based learning

applications or so called serious games, these games

try to teach the players about phishing, malware,

encryption and other important topics among the

cyber security landscape.

The term ‘serious game’ was originally defined

by Clark Abt in 1970 (Abt, 1970) but was updated

by Mike Zyda in 2005 (Zyda, 2005). We define it as

a game with a purpose other than pure entertainment

(Hendrix et al., 2016). Synonyms are ‘learning

game’ or ‘educational game’ (short edugame). We

also include the term ‘competence developing

games’ defined by König et al. in 2016 (König and

Wolf, 2016). As for game-based learning, we define

it as learning by playing a game. Often the prefix

‘digital’ is added to highlight the use of digital

learning games, but in its origin it is just about fun

and engagement joined with the serious activity of

learning (Prensky, 2001).

While serious games are often part of research

projects and get developed systematically or rapidly,

after their evaluation they often disappear and are

rarely available to the public.

Another drawback of these games is the target

audience. Very prominent examples are targeted at

Computer Science (CS) or Engineering students at

university level or employees in similar fields. This

target audience seeks learning opportunities in the

area of cyber security due to their interests and field

of study or work. Often, respective games are used

in university courses or as on-the-job training to

gamify learning and serve as an exploratory learning

opportunity.

When it comes to end-users without strong

interests in cyber security, the objectives differ.

Serious games for cyber security should engage end-

users to learn about a rather difficult topic since they

lack foundational knowledge in the field of CS.

58

Roepke, R. and Schroeder, U.

The Problem with Teaching Defence against the Dark Arts: A Review of Game-based Learning Applications and Serious Games for Cyber Secur ity Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0007706100580066

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 58-66

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

They are used to motivate end-users and keep them

entertained while learning about a topic that seems

complicated and too hard to learn. Without

respective knowledge, end-users can find it very

difficult to assess the risks associated with using the

Internet and IT systems. They do not know how to

behave safely. The problem results in end-users

who, of course, continue to use today’s technology

and the Internet but are unaware of potential risks

and measures to secure themselves.

As part of the ERBSE project

1

, which stands for

“Enable Risk-aware Behavior to Secure End-users”,

we look at existing game-based approaches on risk

awareness and cyber security. We focus on the area

of conflict between the high complexity of cyber

security and end-users without previous IT

education. The goal of the project is to implement

and evaluate game-based approaches for cyber

security education to enable end-users in risk

assessment and suitable behaviour when using IT

systems and the Internet.

In this work, we present a systematic review of

game-based learning applications and serious games

for cyber security education. The underlying

hypothesis is that there are not many game-based

learning applications and serious games about cyber

security, which are targeted at end-users without

prior knowledge in CS. In addition, we hypothesize

that those available, existing games for respective

end-users do not teach sustainable skills and

knowledge of CS to properly educate end-users to

behave securely and assess risk suitably.

We are aware of research on serious games for

cyber security education, but we expect that most

work terminate after evaluating research prototypes.

Where one prototype game has proven to be

effective, it seems to disappear afterwards and does

not make it to the public to educate end-users. So,

similar to the teaching problem at Hogwarts,

effective game-based approaches to teach about

cyber security do not last.

The remaining paper is structured as follows:

First, related work and lessons learned are presented.

Next, the methodology of literature review including

stepwise filtering is explained and results are

presented. Last, a discussion of the results and

conclusion with focus on future work follows.

1

https://nerd.nrw/de/forschungstandems/erbse/, last

accessed on 2018-12-10

2 RELATED WORK

Prior to this work, various authors also reviewed

approaches of cyber security education. Some

focussed on game-based learning and compared it to

traditional training approaches. Others compared

different serious games or gamified concepts to give

an overview on the state of the art.

Tioh et al. provide a comparison of traditional

training and hands-on training and emphasize that

game-based learning can combine the characteristics

of both training methods to more effectively educate

users. In the next step, they identified a set of

academic prototypes as well as products available on

the market. For each, they identified game type and

topic. For academic prototypes, Tioh et al. also

reviewed related studies but identified that

effectiveness was not yet empirically shown. (Tioh

et al., 2017)

A similar review by Hendrix et al. confirmed the

same need for training of both public and businesses.

While the results of analysed studies indicate

positive effects, the sample sizes are small and no

effect sizes have been properly discussed. (Hendrix

et al., 2016) In addition, the samples were drawn

from various target groups, which may weaken the

observed effects as well. Hendrix et al. also stated

the research prototypes were either hard to find or

not available at all.

Compte et al. analysed some serious games for

information assurance and stated observations and

suggestions regarding the design of serious games

for cyber security education. A serious game tries to

serve as an immersive experience and often

simulations are chosen to deliver the game content

(Compte et al., 2015). Since most games are used in

educational settings like academia or schools, time

constraints limit the use of the game, although Pastor

et al. argue that players should be able to play a

serious game “in their own environment” (Pastor et

al., 2010) and also, virtually, the time constraint

does not exist (Compte et al., 2015).

In another review of gaming technology for

cyber security education by Alotaibi et al., various

studies were compared. Alotaibi et al. state that the

approach of gaming to raise awareness is relatively

new and needs more extensive research. They

suggest streamlining gaming techniques necessary to

raise awareness to all different kinds of threats. In

the next step, they analysed ten popular cyber

security games available online on the aspects of

game type, target audience and intended learning.

According to their review, most games target

students or teenagers. Depending on the content they

The Problem with Teaching Defence against the Dark Arts: A Review of Game-based Learning Applications and Serious Games for Cyber

Security Education

59

may also be suitable for professionals or employees

in specific fields of work. (Alotaibi et al., 2016)

While most reviews focus on digital games using

simulations, 2D or 3D environments, Dewey and

Shaffer also highlighted available tabletop games,

such as [d0x3D!] or Control-Alt-Hack ® (Denning

et al., 2013). Both games showcase security

concepts related to network and computer security to

end-users, e.g. younger adults (Gondree et al., 2013).

The benefits of tabletop games include accessibility,

modifiability as well as their potential for social

interaction. They are also cheap and easy to set up.

(Gondree et al., 2013)

Another concept which aligns with the strong

trend of simulations are virtual laboratories to gain

hands-on experience and connect theory and practice

(Dewey and Shaffer, 2016; Son et al., 2012).

Even more practice can be enforced in cyber

security competitions such as “Capture The Flag”

(CTF) events or hack-a-thons. These types of games

are often described as open challenges where no

solution might be handed out at the end. Often the

challenge may persist after the competitions

deadline (Gondree et al., 2016). The web site

CTFtime reports more than 140 CTFs alone for 2017

(currently 148 for 2018). More than 70% are

available online and accessible to anyone. (CTFtime,

2018)

Due to the competitive nature of CTFs they often

attract players with background knowledge in cyber

security, e.g. CS students or professionals. In

general, they appear to be open to the public, but the

challenges may be too hard for players without

guidance or proper background knowledge.

Although all reviews try to classify available

games based on their target audience, used

technology, game type or content, they all approach

the concept of game-based learning applications and

serious games somehow differently. While most

research prototypes have been evaluated and

indicate positive effects, the sample sizes were

rather small and from various target groups (Hendrix

et al., 2016; Tioh et al., 2017). Also, many research

prototypes are no longer available or very hard to

find (Hendrix et al., 2016).

In the following, we present a more holistic

review approach where all contributions are divided

by types, target groups and educational contexts.

3 METHODOLOGY

As the field of games develops rapidly, driven by

academic and commercial settings, a systematic

literature review alone does possibly not cover all

available serious games and game-based learning

applications in the field of cyber security. Hence, a

two-fold review process is necessary where on the

one hand a systematic literature on academic

publications is performed and on the other hand, a

product search is executed with a search engine.

For the systematic literature review, we first

chose two keyword sets, one with cyber security

related terms and a second one with terms regarding

game-based learning and serious games. These

keyword sets contain the most suitable keywords in

their category but are not expected to be complete in

coverage of all publications.

The keyword sets are defined as follows:

ITsec = {IT security, cyber security, risk

awareness, security awareness, security

education, cyber education, security}

(1)

LearnTech = {game based learning,

gamification, serious game, learning game,

edugame, teaching game, competence

developing game}

(2)

All combinations of two keywords, one of each

set are used for search requests. For the retrieval

process, the following three digital libraries and/or

search engines are used: IEEE Xplore

2

, Google

Scholar

3

and ACM Digital Library

4

. On each

request, the first 100 results are extracted for further

analysis (if less search results returned, all results are

used). We limit ourselves to the first 100 results

since with an even lower rank the result may be less

suitable to our search queries.

With all retrieved results, a multiple-step

filtering and classification process is performed to

systematically review all extracted publications.

In the first step, all duplicates are removed to

reduce the result set. Afterwards, online availability

and accessibility (via university library access or

open access) is determined and all results that are

not available to read are excluded.

The third step is filtering all results based on the

leading question: whether a publication is about

cyber security education or not. We exclude all off-

topic results to reduce the result set.

With the reduced result set, a categorization is

attempted. All results are sorted into the following

categories: competition, game, gamification, review,

and other. Here, ‘other’ included all publications on

2

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/, last accessed on 2018-11-22

3

https://scholar.google.de/, last accessed on 2018-11-22

4

https://dl.acm.org/, last accessed on 2018-11-22

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

60

frameworks, tools and further cyber security

education content that does not fit any other

category.

In the next step, all results categorized as reviews

are processed and all serious games or game-based

learning applications cited are added to the result set

for further processing. This measure prevents the

non-finding of games already reviewed by other

authors.

For all results categorized as ‘game’,

‘competition’ or ‘gamification’ as well as all games

retrieved from reviews in the previous step we then

analysed further in the next step. For each

publication, we determine the topic with regards to

cyber security, the game name (if applies), the

respective target group and the intended educational

context.

Lastly, for all identified games, their online

availability is checked. Since board games or card

games are by design offline, online availability

refers to online available information or similar.

After completing all steps of the multi-step

filtering approach, the literature review is done.

Next, the product search for serious games and

game-based learning applications on cyber security

is performed using the Google search

5

.

All games found by the product search are added

to the result set of the literature review and the topic,

target group and educational context is determined

to complete the analysis.

4 RESULTS

After the retrieval process using the two keyword

sets ITsec and LearnTech, the initial result set

contained 2636 publications. This set was reduced to

1277 results by eliminating duplicates. Next, all

available results were filtered based on the question

whether they are about cyber security education by

any means. The result set was reduced to 183

publications.

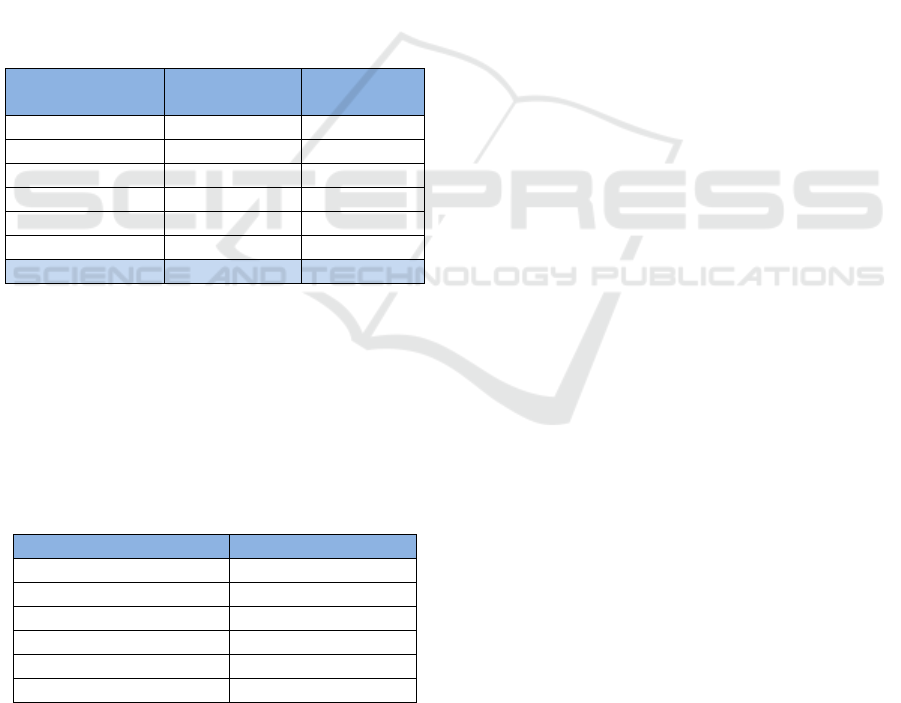

Table 1: Cumulative Overview of Results.

Type

# Results

Game

133

Gamification

24

Competition

24

Σ = 181

Review

14

Other

21

5

https://www.google.com, last accessed on 2018-11-26

Including the games mentioned in other reviews

as well as the product search, the result set got

extended to 216 results. Within this set, 181 results

are of type ‘game’, ‘gamification’ or ‘competition’

(as shown in Table 1).

Next, we started processing the partial result sets

categorized as ‘competition’ or ‘gamification’. Since

competitions are most likely CTFs or other cyber

security challenges which often incorporate game

mechanics but are rather different to game-based

learning applications and serious games, we are

certain that we did not discover a representative

portion of available competitions. Our keyword set

was focussed on serious games and game-based

learning and did not focus on challenges or

competitions.

Also, the nature of CTFs and other cyber security

challenges is more competitive than serious games.

Participants in such competitions are highly

motivated to win and therefore pursue significant

training and research in this domain. Compared to

serious games, where learners play for entertainment

and learn by playing, to succeed in a competition the

participants teach themselves to, e.g., build strong

systems, attack their opponents and defend

themselves. They are encouraged to get a deeper

understanding of cyber security which exceeds the

expected level of education for end-users in this

domain.

Reviewing the 24 results on competitions we

discovered that almost 2/3 are targeted at CS

students, or professionals. While 1/3 may be suitable

for other students or end-users, they still are more

attractive to participants, which are interested in CS

and cyber security topics. The end-users we are

interested in are different and are not likely to take

part in competitions about cyber security. Hence, we

ignore all results categorized as competitions in our

further analysis and discussion. Although, we

strongly suggest looking further into competitions

and used game technologies for end-user education.

24 results were categorized as ‘gamification’ due

to their incorporation of gamification approaches to

educate users. We distinguish gamification and

game-based learning. To our understanding,

gamification is the use of game elements in a rather

traditional learning context, such as scoring,

rankings or avatars. We use the definition of

Deterding et al. that “gamification is the use of game

design elements in non-game contexts” (Deterding

et al., 2011).

Therefore, our further analysis and discussion

will also disregard the results categorized as

‘gamification’ and will instead focus purely on

The Problem with Teaching Defence against the Dark Arts: A Review of Game-based Learning Applications and Serious Games for Cyber

Security Education

61

games. This leaves us with 133 results on game-

based approaches in cyber security education.

For all results categorized as games we

continued the analysis and determined the respective

topics, game names, target groups and the intended

educational context.

We identified 99 different serious games or

game-based learning applications. Possible target

groups are CS students, employees, end-users,

parents/teachers, professionals and students.

While the number of identified games may seem

large, the online availability is a crucial criterion to

interpret the results further. Games which are not

available online (web-based or for download), are

not available to the respective target group. As Table

2 shows, only 48 out of 99 games are available

online. Note that board games and card games are

‘available online’ if they are still sold or available

for download and print.

Table 2: Distribution of target groups among games.

Target Group

# Games

Available

online

CS students

19

5

Employees

12

7

End-users

26

12

Parents/Teachers

1

1

Professionals

9

5

Students

32

18

Σ = 99

Σ = 48

Regarding the educational context, various

contexts appear. We distinguished between Primary

School, Middle School, High School,

College/University, Corporate and Non-formal

context. Since some games can be used in more than

one context, we applied multi-label classification on

all identified games.

Table 3: Results of Educational Context Analysis using

multi-label classification.

Educational Context

# Games

Primary School

4

Middle School

9

High School

10

College/University

26

Corporate

20

Non-formal

38

Most games are designed for colleges,

universities as well as corporate and non-formal

contexts (see Table 3). This is not surprising since

there is no complete coverage of CS among primary

and secondary schools and hence, cyber security

education is covered even less.

Since many games are designed as research

prototypes, they are often designed for students in

college or university. These games may serve a

specific educational context but can also be open for

end-users in non-formal learning contexts.

Games for corporate use are often developed

professionally and may be used for training purposes

of employees or professionals. These games are less

suitable for the public, e.g. they simulate corporate

environments to create an authentic learning

experience. They are also often related to cyber

security within companies and hence, they differ

from security for end-users in their private life.

Regarding the analysis of game topics, there is

no clear result but rather a variety of topics that were

identified. Ranging from forensics, hacking and

network security to phishing, social engineering and

online safety, available games often cover more than

one topic.

The overall result of our two-fold approach to

review game-based learning applications and serious

games in the domain of cyber security contains a set

of 99 games, found in either academic publications

or through a product search. Further analysis provide

insight on respective target groups and intended

educational contexts.

5 DISCUSSION

After describing the results of our systematic

literature review and product search, we now

interpret them to respond to our hypotheses stated

earlier. Our first hypothesis was that there are not

many game-based learning applications and serious

games about cyber security, which are targeted at

end-users without prior knowledge in CS.

As shown in Table 2, there are various target

groups for games in cyber security education.

Regarding the prior knowledge in CS, a large

portion of games is targeted at end-users with no

prior knowledge. We identified that 58 games are

targeted at end-users (26 results) and non-CS

students (32 results). Since not all of them are

currently publicly available, we need to focus on the

30 out of 48 games for end-users and non-CS

students that are available online.

At first, this result seems to falsify our

hypothesis. More than 60% of available game-based

learning applications and serious games on cyber

security are targeted at end-users without prior

knowledge or skills in CS.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

62

Regarding our second hypothesis, a closer look

on the available results is necessary. We are looking

for games that teach sustainable skills and

knowledge in CS to properly qualify end-users to

behave securely and assess risk suitably. Therefore,

we will present a few games of our result set and

analyse them.

At first, we looked at “The Internet Safety

Game”, available on the platform “NetSmartKidz”

by the National Center for Missing & Exploited

Children

6

. It is a web-based game on safety in the

Internet and targets younger children in non-formal

learning contexts. The game consists of a board-

game-like environment with a character that can be

moved stepwise when rolling a dice (see Figure 1).

The task is to collect various items on the board.

These items are pieces of information, which teach

the player facts about the Internet. There is a total of

six items to be found and afterwards, the player wins

the game. Based on the difficulty level, optional

assessment in a multiple-choice fashion is available

to test the player on the collected facts. The facts

include the recommendation about not sharing

personal information (e.g. name, age, or address)

online. While this may seem to be a reasonable

suggestion there is no explanation on what risks are

connected to it.

Figure 1: Screenshot of “The Internet Safety Game”.

Next, PASDJO is a game by Seitz and

Hussmann

7

. In this game, the player rates a set of

passwords and gets feedback on the quality of

passwords accordingly (Seitz and Hussmann, 2017).

The game is very short and its gameplay is rather

simple. Although there is feedback on passwords

6

https://www.netsmartzkids.org/AdventureGames/

TheInternetSafetyGame, last accessed on 2018-11-29

7

https://password-game.firebaseapp.com/, last accessed

on 2018-11-29.

and their quality, the whole topic of password

strength is not addressed very thoroughly. Potential

adversary models and risks of poor passwords are

not addressed, which is why this game does not

teach sustainable skills and knowledge on CS.

The third example application, we present, is the

“Safe Online Surfing” platform by the Federal

Bureau of Investigation (FBI). It is a set of mini

games for different age groups raging from grade 3

to 8. The game covers topics like online safety and

the Internet. While this platform uses various game

mechanisms to engage the players, the skills and

knowledge taught in the games are rather arbitrary

and not motivated properly. Again, the content is

missing aspects like risks and threat models and it

does not emphasize the relevance of certain topics.

The knowledge gained is only factual knowledge

and hence, it is not sustainable due to the rapidly

changing face of cyber security.

Another game is CyberCIEGE, a research

prototype by the Naval Postgraduate School, which

made it to the public and is available for download

8

.

CyberCIEGE is setup as an interactive environment

where players learn about computer and network

security. The player acts as an employee of a

company and is responsible for the configuration of

firewalls, VPNs and other security related systems

(see Figure 2). The game is more complex and

provides different scenarios. Various attack

scenarios include viruses, trojan horses, malicious e-

mail attachments and more. It also adresses more

sufficient skills and knowledge in CS. It was used in

various studies to evaluate its effectiveness (Ariffin

et al., 2016; Irvine et al., 2005; Raman et al., 2014).

Figure 2: Screenshot of CyberCIEGE.

8

https://my.nps.edu/web/c3o/cyberciege, last accessed on

2018-12-06.

The Problem with Teaching Defence against the Dark Arts: A Review of Game-based Learning Applications and Serious Games for Cyber

Security Education

63

While it may be a candidate that teaches

sustainable skills and knowledge of CS to enable

end-users to risk-aware behavior, the availability of

various scenarios makes it harder to enter the game.

It was used in various educational contexts, but

always somehow supported by a teacher or

instructor. The developers of CyberCIEGE also

provide supportive materials to include the game

into introductory courses to cyber security, e.g. a

syllabus matching scenarios to possible course

topics.

Compared to platforms like NetSmartKidz or

“Safe Online Surfing”, CyberCIEGE may be a

suitable approach content-wise but its entry points

may be hindering its success among end-users in

non-formal learning contexts. For end-users in non-

formal learning contexts, a game about cyber

security requires easy access. There should be no

hassle like setting up a complex environment in

order to play the game.

After presenting four different games for end-

users and pointing out their weaknesses, we can

summarize and respond to our hypothesis. Games

like “The Internet Safety Game” or the “Safe Online

Surfing” platform are designed for younger children

in non-formal learning contexts, while PASDJO or

CyberCIEGE may be more suitable for older target

groups. While all games are for end-users without

prior knowledge and skills in CS, they are also very

limited when it comes to qualifying players in cyber

security.

Games like PASDJO and “The Internet Safety

Game” present information of the cyber security

domain, e.g. passwords, without context. They fail

to answer why the respective topics are important

and do not elaborate on risks. Without establishment

of relevance, the factual knowledge in these games

stays unconnected.

Another drawback of theses games is the way of

presentation. For example, PASDJO just presents

passwords and ask the user to rate them. After rating

the first passwords the gameplay becomes repetitive

and boring. Mini games on the “Safe Online

Surfing” platform implement various gameplays but

are still missing relevance for the factual knowledge

they teach.

Regarding our second hypothesis, that available

games for end-users do not teach sustainable

knowledge or skills in CS, first indicators seem to

verify the hypothesis. First, presented games are

missing relevance and information on risks,

adversary models and quality of security measures.

They are also very limited, since most of them only

teach factual knowledge. While CyberCIEGE may

also focus on conceptual or procedural knowledge,

its entry points and high complexity are drawbacks.

To actually teach more sustainable knowledge or

skills in CS, we need to teach a mixture of factual,

conceptual and procedural knowledge. Game-based

approaches need to create relevance for the content

and answer immanent questions regarding why to

learn about a topic of cyber security and what the

risks are.

Due to constant change in cyber security, i.e.

adversary trying new techniques, using hidden

backdoors or relying on unaware users, teaching

cyber security needs to be sustainable in a way that

users can use the gained knowledge or skills and

adapt them to new challenges in cyber security.

They still need to continue learning about new risks

but with foundational skills and knowledge from

previous learning opportunities this should be less

challenging than before.

Overall, we responded to our two hypotheses by

analysing the results of our two-fold retrieval

process. While the first hypothesis was falsified due

to the availability of various games for end-users,

employees and non-CS students, the most games

currently available to the public do not teach

sustainable knowledge or skills in CS. They may

implement various game mechanisms to engage the

user, but they do not emphasize relevance, risks and

quality of security measures. The content of the

games is missing essential context such that players

may have difficulties learning properly about the

respective topics.

6 CONCLUSION

Motivated by the problem of finding a suitable and

lasting teacher for the Defence against the Dark Arts

class at Hogwarts, we reviewed game-based learning

applications and serious games in the domain of

cyber security as they are an approach to teach users

defence against today’s dark arts, i.e. phishing,

malware et cetera.

After presenting a two-fold approach including a

systematic literature and a product search, a set of

216 results was available for further classification.

We identified 181 results on games, competitions

and gamification. We excluded all results on

competitions and gamification since they are either

not targeting end-users without prior knowledge or

skills in CS or are relying on a different concept than

game-based learning. Afterwards, all games were

analysed on aspects like topics, target group and

educational context. Also, online availability was

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

64

determined since it is a crucial factor for end-users

looking for games on cyber security. Finally, we

identified 48 available games for different target

groups (see Table 2) and educational contexts (see

Table 3).

In the next step, we discussed our two

hypotheses with respect to the results of our

analysis. At first, we falsified the first hypothesis

that there are not many games for end-users without

prior knowledge or skills in CS. More than 2/3 of the

available games are targeted at end-users, non-CS

students and employees.

Further, we hypothesized that available games

for end-users do not teach sustainable knowledge or

skills in CS. By presenting a few of the available

games we found indicators verifying our hypothesis.

First, the games mostly rely on factual knowledge

without proper context. Often relevance is missing.

Also, there is no emphasis on risks, adversary

models and the quality of security measures.

For future work we propose to further analyse

the result set of our two-fold retrieval process. As it

is our goal to establish the state of the art on game-

based learning applications and serious games on

cyber security for the target group of end-users, we

are interested in the results of studies made with

such games. Interesting aspects can also be the used

game mechanisms and themes.

Afterwards, we propose to design new game

prototypes for end-users and implement lessons

learned from available games. Incorporated in the

ERBSE project, we want to implement and evaluate

game-based approaches for cyber security education

to enable end-users in risk assessment and suitable

behaviour when using IT systems and the Internet.

As we already established, missing context,

relevance and information on risks, adversaries and

quality of security measures should be incorporate in

game prototypes in order to teach sustainable

knowledge and skills in CS. Otherwise we would

end up with another set of games not offering what

would be valuable for end-users. In other words, our

approaches would not last, like the teachers for

Defence against the Dark Arts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the research training

group "Human Centered Systems Security"

sponsored by the state of North-Rhine Westphalia.

REFERENCES

Abt, C.C., 1970. Serious games. New York: Viking Press.

Alotaibi, F., Furnell, S., Stengel, I., and Papadaki, M.,

2016. A review of using gaming technology for cyber-

security awareness. Int. J. Inf. Secur. Res.(IJISR),

6(2):660–666.

Ariffin, M.M., Ahmad, W.F.W., Sulaiman, S., 2016.

Investigating the educational effectiveness of

gamebased learning for IT education, in: 2016 3rd

International Conference on Computer and

Information Sciences (ICCOINS). Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia, pp. 570–573.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCOINS.2016.7783278

Compte, A.L., Elizondo, D., Watson, T., 2015. A renewed

approach to serious games for cyber security, in: 2015

7th International Conference on Cyber Conflict:

Architectures in Cyberspace. Tallinn, Estonia, pp.

203–216.

https://doi.org/10.1109/CYCON.2015.7158478

CTFtime, 2018. CTFtime.org / All about CTF (Capture

The Flag).

Denning, T., Lerner, A., Shostack, A., Kohno, T., 2013.

Control-Alt-Hack: the design and evaluation of a card

game for computer security awareness and education,

in: Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC

Conference on Computer & Communications

Security. ACM, pp. 915–928.

Deterding, S., Khaled, R., Nacke, L.E., Dixon, D., 2011.

Gamification: Toward a definition, in: CHI 2011

Gamification Workshop Proceedings. Vancouver BC,

Canada.

Dewey, C.M., Shaffer, C., 2016. Advances in information

SEcurity EDucation, in: 2016 IEEE International

Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT).

Grand Forks, ND, USA, pp. 0133–0138.

https://doi.org/10.1109/EIT.2016.7535227

Gondree, M., Peterson, Z.N., Denning, T., 2013. Security

through play. IEEE Security & Privacy 64–67.

Gondree, M., Peterson, Z.N., Pusey, P., 2016. Talking

about talking about cybersecurity games.

Hendrix, M., Al-Sherbaz, A., Victoria, B., 2016. Game

based cyber security training: are serious games

suitable for cyber security training? International

Journal of Serious Games 3, 53–61.

Irvine, C.E., Thompson, M.F., Allen, K., 2005.

CyberCIEGE: gaming for information assurance.

IEEE Security Privacy 3, 61–64.

https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2005.64

König, J.A., Wolf, M.R., 2016. A New Definition of

Competence Developing Games, in: Proceedings of

the Ninth International Conference on Advances in

Computer-Human Interactions. pp. 95–97.

Pastor, V., Díaz, G. and Castro, M., 2010. State-of-the-art

simulation systems for information security education,

training and awareness, in: IEEE Education

Engineering (EDUCON), Madrid, Spain, pp. 1907–

1916.

Prensky, M., 2001. Digital game-based learning, McGraw-

Hill & Paragon House, New York.

The Problem with Teaching Defence against the Dark Arts: A Review of Game-based Learning Applications and Serious Games for Cyber

Security Education

65

Raman, R., Lal, A., Achuthan, K., 2014. Serious games

based approach to cyber security concept learning:

Indian context, in: 2014 International Conference on

Green Computing Communication and Electrical

Engineering (ICGCCEE). Coimbatore, India, pp. 1–5.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICGCCEE.2014.6921392

Seitz, T., Hussmann, H., 2017. PASDJO: Quantifying

Password Strength Perceptions with an Online Game,

in: Proceedings of the 29th Australian Conference on

Computer-Human Interaction, OZCHI ’17. ACM,

New York, NY, USA, pp. 117–125.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3152771.3152784

Son, J., Irrechukwu, C., Fitzgibbons, P., 2012. Virtual lab

for online cyber security education. Communications

of the IIMA 12, 5.

Tioh, J.-N., Mina, M., Jacobson, D.W., 2017. Cyber

security training a survey of serious games in cyber

security, in: Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE).

IEEE, pp. 1–5.

Zyda, M., 2005. From visual simulation to virtual reality

to games. Computer 38, 25–32.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

66