Investigation of Sound-Gustatory Synesthesia in a Coffeehouse

Setting

Nicole Ashley V. Santos and Maria Teresa R. Pulido

Department of Physics, Mapúa University, Intramuros, Manila City, 1002, Philippines

Keywords: Psychophysics, Synesthesia, Surveys, Data Analysis.

Abstract: Synesthesia is a perceptual phenomenon involving the stimulation of multiple senses. In this work, we

determine the presence of sound-gustatory synesthesia by looking at the possible effects of background

music on the perceived taste of a coffee-sugar mixture. We asked participants (N = 83) to listen to music

while identifying the tastes they perceived drinking a coffee-sugar sample. Our results showed that

sweetness was perceived more while listening to the “Slow” music, which is consistent with previous work.

The perception of sourness also increased with the tempo of the music, consistent with work associating

sourness with pitch. Interestingly, participants also perceived saltiness and sourness even though the

ingredients did not contain ingredients with those tastes, which provides further evidence of sound

influencing taste perception. This study has shown the presence of sound-gustatory synesthesia in a typical

coffeehouse setting, introducing potential applications in psychophysics, food science, and other complex

systems research. Our algorithm has also shown how quantitative tools can be used in a qualitative field

such as psychological perception. We expect multisensory, interconnected technology in the Internet of

Things to spread the experience of synesthesia within a population, with Big Data enabling researchers to

detect and measure synesthesia much more accurately.

1 INTRODUCTION

Humans make use of sensory information to

determine environmental properties (Hillis, et al.,

2002). Synesthesia is the simultaneous perception

of two or more stimuli as one experience, even

when the external stimulation of the additional

perceived sense is absent (Colizoli, et al., 2013;

van Campen, 2009). Only around two to four

percent of a population have some form of

synaesthesia, and its origins are not yet clearly

determined (Brang and Ramachandran, 2011).

However, with the arrival of multisensory

technology and the interconnectedness of Big Data,

we expect a proportional increase in the

manifestation and detection of synaesthesia.

In particular, flavor perception makes use of

multisensory integration of all other human senses

(Spence, 2015). Gustatory synaesthesia involves

the automatic and consistent experience of tastes

that are activated by non-taste related inducers

(Colizoli, et al., 2013), such as music (sound-

gustatory) and words (lexical-gustatory) (Gallace,

at al., 2011; Bankieris and Simner, 2013). In a

study by Mesz, Sigman and Trevisan (2012),

“Sweetness” is associated with high pitched,

consonant, slow, and soft music, “Bitterness” is

associated with low pitch and continuous music,

“Saltiness” is perceived more when the music have

silences between notes, and “Sourness” is with

high pitched, dissonant and fast music. Perceptual

associations between taste and different aspects of

sounds (pitch, timbre, interval, or tempo) can lead

to predictions about the effects of musical pieces

on gustatory perception (Knöferle and Spence,

2012; Crisinel and Spence, 2009).

Sound-gustatory synesthesia has been initially

investigated in terms of how pleasure, associated

with sound in the form of music or noise, affects

taste as well. With the music used as a component

of sound, the experience of drinking beer was rated

more enjoyable with music than when in silence

(Reinoso Carvalho, et al., 2016). Meanwhile, gelati

consumed while listening to liked and neutral

music had positive scores, while gelati consumed

while listening to disliked music had negative

scores (Kantono, et al., 2016). Meanwhile,

background noise has been shown to reduce the

294

Santos, N. and Pulido, M.

Investigation of Sound-Gustatory Synesthesia in a Coffeehouse Setting.

DOI: 10.5220/0007719502940298

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (IoTBDS 2019), pages 294-298

ISBN: 978-989-758-369-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

intensity of gustatory cues and increase the

intensity of sound-conveyed food attributes

(Woods, et al., 2011).

In this work, we investigate sound-gustatory

synesthesia in a typical coffeehouse setting, by

looking at the possible effects of background music

on the perceived taste of coffee-sugar drinks. In

particular, we asked participants which particular

tastes they perceived upon listening to a type of

music. Through this work, we hope to learn more

about the interconnectedness of sensory perception

within the complex system of the human body. We

are also interested in the potential applications of

this work to food science and to improving the

customer experience in the food and beverage

industry. Chefs and related professionals actively

apply the latest scientific findings to their own work

(Spence, 2015).

2 METHODOLOGY

The researchers downloaded coffeehouse

background music (Jazz and Blues Experience,

2016) and used Wondershare Filmora video editor

to vary the music speed or tempo (Figure 1).

Compared to the original music track (“Normal”),

the “Fast” track was 5.000 times faster, and the

“Slow” track was 0.230 times slower. Different 60-

second segments of the music track were used for

the three tracks, to minimize the possibility of

participants making conscious associations

between the music and the coffee. The participants

(N = 83) were composed of college students, senior

high students, and some faculty members of the

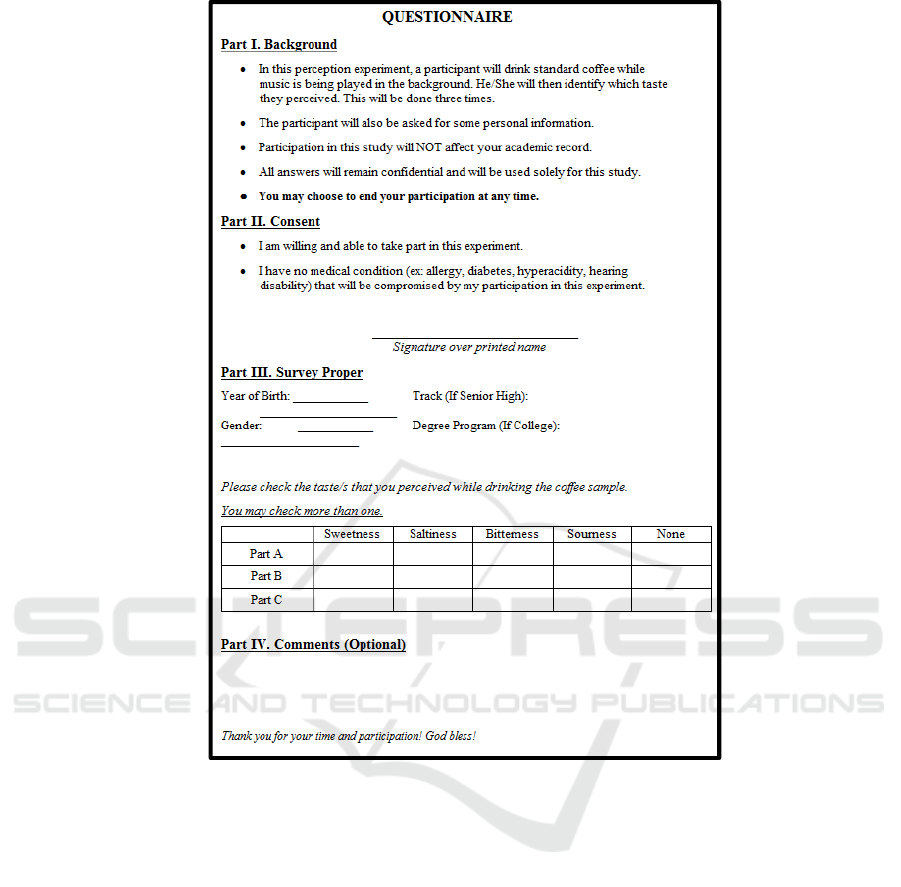

Mapúa University. They were presented with an

overview of the nature and purpose of the

experiment. The researchers also explained that

participation was completely voluntary and will not

affect their academic standing. Participants who

chose to stay were asked to fill up the questionnaire

provided (Figure 2).

At the start of each trial, participants were

asked to sip some water to cleanse the palate. A

music track was then played for 1 minute. During

this time, participants were asked to taste a new

5.00-cc coffee-sugar sample and report their

perceived tastes on their questionnaire. The

participants may select more than one taste per

trial; alternately, they may answer “None”.

Trials “A”, “B” and “C” made use of the

“Normal”, “Fast”, and “Slow” tracks respectively.

Participants were given 3 samples marked “A”, “B”,

and “C”, but these samples involved the same

mixture (equal parts coffee and sugar dissolved in

warm water), to limit the variability in the

experiment. All experiments were performed in a

classroom within one day, with around 15 to 30

participants for each batch.

Figure 1: Screenshot of the video editor used.

Investigation of Sound-Gustatory Synesthesia in a Coffeehouse Setting

295

Figure 2: The questionnaire used in the experiment.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall, Bitterness and Sweetness were the

dominant perceived tastes, as expected from samples

containing bitter coffee and sweet sugar (Figure 3).

The tallied answers for each trial exceeded 100% as

participants may select more than one answer.

A significantly large majority (53.33%)

perceived Sweetness for the “Slow” trial, while

Bitterness was dominant taste for the “Normal”

(56.93%) and “Fast” (43.05%) trials. The results are

consistent with previous studies associating

sweetness with slow music (Mesz, et al., 2012),

presumably influencing participants to sense

“Sweetness” in a predominantly bitter drink. We

note that Mesz, Sigman and Trevisan (2012) also

associated bitterness with low pitch, which are not

necessarily in contrast with our results, as the speed

of a music track may be increased without

necessarily increasing its pitch.

Interestingly, a notable portion of responses

perceived Sourness and Saltiness even though the

samples did not contain sour nor salty components;

while a significant minority also selected “None” for

the perceived taste. Such results are evidence of taste

perception as opposed to objective taste.

Lastly, the perception of Sourness increased with

the speed of the background music: from 9.17% to

18.98% to 24.50%, for “Slow” to “Normal” to

“Fast” music, respectively. This is consistent with

previous work associating sourness and pitch (Mesz,

2012), when we consider that pitch is proportional to

speed.

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

296

Figure 3: The tastes perceived by the respondents listening to music played at three different speeds

.

Investigation of Sound-Gustatory Synesthesia in a Coffeehouse Setting

297

4 CONCLUSIONS

This initial work has demonstrated the presence of

sound-gustatory synesthesia in a typical coffeehouse

setting. We have seen that the speed of the music

being heard may alter the perception of the coffee

being tasted. In particular, majority of the

participants detected Sweetness when Slow music

was played, and Bitterness when Normal and Fast

music were played. Participants also perceived

Sourness and Saltiness, and the perception of

Sourness increased with the speed of the music

track, even when sour and salty components were

not present in their drinks.

We can improve the study by including baseline

measurements for taste (water) and sound (no

music). Stafford, Fernandes, and Agobiani (2012)

have shown that the presence of music altered taste

perception, serving as a “distraction” in the same

way as shadow multitasking.

To extend the previous sound-gustatory

synesthesia research, we can also have participants

ask if they inherently “like” or “dislike” the drink

and the music tested, to investigate associations

between hedonic and sensory perception of coffee.

Lastly, we can also look for possible effects of

respondent traits such as gender and age.

We expect multisensory, interconnected

technology in the Internet of Things to spread the

experience of synesthesia within a population, with

Big Data enabling researchers to detect and measure

synesthesia much more accurately.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the students and faculty of Mapúa

University for participating in the study, the

Yuchengco Innovation Center for the resources in

preparing this manuscript, and our colleagues and

loved ones for their support. We also thank the

organizers of the IoTBDS 2019 Conference for

accepting this work and for the financial support.

REFERENCES

Bankieris, K. and Simner, J., 2013. Sound symbolism in

synesthesia: Evidence from a lexical-gustatory

synesthete. Neurocase, 20(6), pp.640-651.

Brang, D. and Ramachandran, V. S., 2011. Survival of the

synesthesia gene: Why do people hear colors and taste

words? PLoS biology, 9(11), e1001205.

Colizoli, O., Murre, J.M. and Rouw, R., 2013. A taste for

words and sounds: a case of lexical-gustatory and

sound-gustatory synesthesia. Frontiers in psychology,

4, p.775.

Crisinel, A.S. and Spence, C., 2009. Implicit association

between basic tastes and pitch. Neuroscience letters,

464(1), pp.39-42.

Gallace, A., Boschin, E. and Spence, C., 2011. On the

taste of “Bouba” and “Kiki”: An exploration of word–

food associations in neurologically normal

participants. Cognitive Neuroscience, 2(1), pp.34-46.

Hillis, J.M., et al., 2002. Combining sensory information:

mandatory fusion within, but not between, senses.

Science, 298(5598), pp.1627-1630.

Jazz and Blues Experience, 2016. New York Jazz Lounge –

Bar Jazz Classics. [Online] Available from:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_sI_Ps7JSEk

[Accessed September 2018].

Kantono, K., et al., 2016. Listening to music can influence

hedonic and sensory perceptions of gelati. Appetite,

100, pp.244-255.

Knöferle, K. and Spence, C., 2012. Crossmodal

correspondences between sounds and tastes.

Psychonomic bulletin and review, pp.1-15.

Mesz, B., Sigman, M. and Trevisan, M., 2012. A

composition algorithm based on crossmodal taste-

music correspondences. Frontiers in Human

Neuroscience, 6, p.71.

Reinoso Carvalho, F., et al., 2016. Music influences

hedonic and taste ratings in beer. Frontiers in

psychology, 7, p.636.

Spence, C., 2015. Multisensory flavor perception. Cell,

161(1), pp.24-35.

Stafford, L.D., Fernandes, M. and Agobiani, E., 2012.

Effects of noise and distraction on alcohol perception.

Food Quality and Preference, 24(1), pp.218-224.

van Campen, C., 2009. The Hidden Sense: On Becoming

Aware of Synesthesia1. Revista Digital de

Tecnologias Cognitivas, 1, pp.1-13.

Woods, A. T., et al., 2011. Effect of background noise on

food perception. Food Quality and Preference, 22(1),

pp.42-47.

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

298