Privacy Perceptions in Ambient Assisted Living

Eva-Maria Schomakers and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer-Interaction Center, Chair for Communication Science,

RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57, 52072 Aachen, Germany

Keywords:

Ambient Assisted Living, Privacy Concerns, Maximum Difference Scaling, Older Adults.

Abstract:

Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) Technologies may help address the challenges that the ageing populations

pose on the health care systems by supporting older adults in ageing-in-place, improving independence, and

quality of care. Technology acceptance by the potential users and particularly privacy concerns are decisive

obstacles to the widespread use of AAL. In order to examine privacy perceptions in detail, 86 participants

(50% older than 50 years) evaluated AAL technologies and privacy concerns in a questionnaire approach.

Additionally, with Maximum Difference Scaling the importance of AAL system characteristics to privacy

perceptions by the users was investigated. Overall, the attitude towards AAL is positive, privacy concerns

regarding the misuse of data, feeling of surveillance, and obtrusiveness of the technology are prevalent but not

tremendous. Who has access to the data is by far the most important characteristic of an AAL system for the

users’ privacy. Prominence of the system, sensor location, and sensor types are least important. The results

contribute an important understanding of how AAL technologies need to be designed to respect users privacy.

1 BACKGROUND

Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) technologies support

older adults in ‘ageing-in-place’ (Peek et al., 2014).

AAL shows the potential to help counteract the dra-

matic challenges that the ageing population poses on

the health care systems. With improving the qual-

ity of health care and independence of older adults,

health care costs, costs for institutionalisation, and

the need for nursing personnel can be reduced (Yusif

et al., 2016; Blackman et al., 2016). At the same time,

most older adults desire to age in place and live as

long as possible independently, in dignity, and with

a high quality of life. Staying at home contributes

to lasting well-being, independence, social participa-

tion, and healthy ageing (Mortenson et al., 2016).

For AAL, no universal and clear-cut definition

exits (Blackman et al., 2016). AAL could best be

translated as ‘age-appropriate assistance systems for

a healthy and independent life’ (Strese et al., 2010).

Under this umbrella term, concepts, products, ser-

vices, and technologies are included that aim at en-

abling people with specific demands, e.g. people with

disabilities or older adults, at all stages of their lives

to live in their preferred environment longer and in-

crease quality of life (Strese et al., 2010).

One tremendous challenge for healthcare systems

as well as for caring families and relatives is the high

proportion of people with dementia (Livingston et al.,

2017). In Germany, 10% of people aged over 65 years

suffered from dementia in 2016 (Deutsche Alzheimer

Gesellschaft e.V., 2016). Family caregivers report a

high level of care strain and show a high probabil-

ity for depression (Jennings et al., 2016). AAL tech-

nologies can assist and monitor older adults in dif-

ferent stages of dementia and thereby improve qual-

ity of life, reduce care needs, and support caregivers

(besides reducing active care effort also in feeling as-

sured of the safety of the patient) (Dupuy et al., 2017).

Examples are the monitoring of daily activities of liv-

ing (e.g., getting up, meal preparation, and physi-

cal hygiene), applications for safety (e.g., automatic

lighting when going to the bathroom at night, door

sensors, and stoves that automatically switch off), for

social participation (e.g., video telephone, informa-

tion about social events), for health monitoring (e.g.,

monitoring of vital parameters, medication intake),

and wayfinding (e.g., GPS tracking, orientation assis-

tance) (Dupuy et al., 2017).

1.1 Technology Acceptance

Despite their promising potential and the ever-

increasing range of products, the demand for and

diffusion of AAL technologies is unexpectedly low

(Hallewell Haslwanter and Fitzpatrick, 2016). The

Schomakers, E. and Ziefle, M.

Privacy Perceptions in Ambient Assisted Living.

DOI: 10.5220/0007719802050212

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2019), pages 205-212

ISBN: 978-989-758-368-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

205

acceptance by potential users is a key factor for the

use and diffusion of new technologies, but can also

constitute a decisive barrier if the needs, desires,

and individual demands of users are not understood

(Legris et al., 2003; Ziefle and Wilkowska, 2010).

The target group of AAL – older adults – is an im-

portant factor for acceptance. Age-related changes in

the cognitive, psychomotor, and perceptive abilities of

older adults may lead to difficulties in handling new

technologies and the great individual differences in

these ageing processes make older adults a very het-

erogeneous user group (Jakobs et al., 2008). In ad-

dition, generation-specific experiences with technol-

ogy influence technology acceptance (Sackmann and

Winkler, 2013). In general, a high willingness to use

new technology can be observed with older adults,

but new technologies are often adopted slower than

in other age groups (Heart and Kalderon, 2013).

Many benefits and barriers for the acceptance of

AAL technologies by the users have been identified

in previous research (Peek et al., 2014). One deci-

sive barrier are privacy concerns (Yusif et al., 2016).

AAL technologies do naturally invade the home of

users. The home is not only a roof over one’s head,

but a multi-faceted, valuable, and intimate place of

living and retreat, which is of great relevance espe-

cially for the elderly (Mortenson et al., 2016). In ad-

dition, the use of various sensors as well as the analy-

sis and transmission of sensitive and intimate data, on

which many AAL technologies are based on, evoke

privacy concerns.

1.2 Privacy Concerns in AAL

Privacy concerns arise when the actual level of pri-

vacy does not equal the desired level of privacy (Li,

2014). The desire for privacy depends largely on

the context and the individual attitudes (Nissenbaum,

2010; Bergstr

¨

om, 2015). Many definitions of privacy

put informational privacy into focus, the control over

personal information (Westin, 1967). But in the con-

text of AAL, other dimensions of privacy are also rel-

evant (Courtney, 2008). AAL technologies may in-

vade the physical privacy (limitation of access to the

physical self), social privacy (control over social con-

tacts, interaction, and communication), and psycho-

logical privacy (limitation of access to thoughts, feel-

ings, and intimate information) (Burgoon, 1982). At

the same time, AAL technologies digitise the access

to the informational, physical, social, and psycholog-

ical self and analyse and transmit data, so that infor-

mation privacy becomes a possible part of the other

privacy dimensions, expanding the audience and per-

sistence of this information (Koops et al., 2017).

In AAL, privacy concerns often regard the feeling

of permanent surveillance, fear of access to and about

misuse of personal information by third parties, but

also about the invasion of personal space, obtrusive-

ness, technical disturbances, and stigmatising design

of the technologies (Kirchbuchner et al., 2015; Peek

et al., 2014; Boise et al., 2013; Wilkowska and Ziefle,

2012). Privacy concerns are influenced by the per-

ceived sensitivity of the collected information: Med-

ical information, especially information about mental

illnesses, are perceived as very sensitive (Valdez and

Ziefle, 2018; Anderson and Agarwal, 2011), again in-

creasing privacy concerns regarding AAL.

On the other hand, AAL technologies show great

potential to support older adults and reduce the bur-

den of family caregivers. For the decision whether to

accept AAL technologies, privacy concerns and other

barriers need to be weighted against the usefulness

of the technology in the individual context (Courtney,

2008; Schomakers et al., 2018). Thus, privacy con-

cerns may be overridden by the benefits and useful-

ness of the technology. For example, Boise and col-

leagues found in their study that users are very willing

to be monitored as the usefulness surpasses privacy

concerns (Boise et al., 2013).

Multiple user studies have identified privacy con-

cerns as major barrier to AAL acceptance (Peek et al.,

2014). But the question arises, what characteristics of

the technology evoke these concerns and how AAL

systems should be designed to protect the users’ pri-

vacy. In a theoretical framework for personal health

information disclosure management, Rashid and col-

leagues identify the intimacy of information (what),

the data receiver (who), and the time granularity and

complexity of the information (how) as important fac-

tors for information privacy in smart home health-

care (Rashid et al., 2007). Regarding the ‘what’, also

the activity sensitivity and type of sensors are impor-

tant (Garg et al., 2014; Himmel and Ziefle, 2016).

For AAL technologies, additionally the placement of

the sensors in the different rooms of the living space

(where) needs to be considered (Kirchbuchner et al.,

2015; Himmel and Ziefle, 2016). As privacy is essen-

tially based on control, control over the technology –

e.g., being able to switch functions off – is another

important condition for the perception of privacy (van

Heek et al., 2017).

1.3 Focus and Aim of the Study

The aim of this research is to understand privacy con-

cerns in AAL and to empirically study how the char-

acteristics of AAL technologies and systems influ-

ence privacy perceptions. What, how, who, where,

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

206

and specific characteristics of the AAL system are

important for the privacy perception of the users, but

which of it is the most important? This study adds

on to previous studies that have identified important

concerns and system attributes that influence privacy

perceptions. In qualitative studies and questionnaires

using traditional rating scales, all these characteris-

tics evolve as important. In this study, concerns and

system characteristics regarding privacy are weighted

in comparison to another to discern the most impor-

tant factors. Using a Maximum Difference Scaling

(MaxDiff) approach, the discrimination between the

factors is in focus to answer the question which sys-

tem characteristics are most important.

2 METHODOLOGICAL

APPROACH

To examine privacy concerns and how system charac-

teristics affect the perception of privacy by the users,

a questionnaire approach with Maximum Difference

Scaling (MaxDiff) tasks was chosen. Beforehand,

three focus group sessions were conducted as pre-

study, in which the participants discussed barriers and

benefits of AAL in general, as well as their concerns

regarding privacy in AAL settings in detail (for de-

tails see (Schomakers and Ziefle, 2019)). Based on

their statements and the preliminary literature study,

the questionnaire items were chosen.

2.1 The Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of four parts. In the first

part, demographic data (age, gender, education level)

and experiences with caring (4 items, e.g., “I expe-

rienced that a close relative was in need for care”)

were assessed. The second part started with introduc-

ing AAL to the participants. A range of technologies

tailored for older adults living alone with dementia –

including smart oven, medication reminders, location

tracking, and emergency detection – were introduced

with short descriptions and visualisations. The expla-

nation ended with the information that different sen-

sors are used for AAL technology (with examples),

that the data may be accessed by different stakehold-

ers (with examples), and in different modalities, e.g.,

only in emergency or as daily summary. After reading

the technology description, the participants evaluated

the benefits and usefulness of AAL technologies on a

semantic differential scale (items in Figure 2). In the

third part of the questionnaire, the participants evalu-

ated five concerns regarding privacy when using AAL

(items in cf. Figure 3). All items were evaluated on

6-point scales. The last part of the questionnaire con-

sisted of the MaxDiff tasks. In an introduction, the

task of choosing the most and the least important was

explained in detail. In the next section, the MaxDiff

tasks are presented.

2.2 Maximum Difference Scaling

Maximum Difference Scaling, also referred to as ‘best

worst scaling’, is a method to obtain preference scores

for multiple attributes. In contrast to rating scales,

it shows greater discrimination among the items and

their relative importance (Sawtooth, 2008). That is,

when asking participants, what is important to them

regarding privacy in AAL, all items are somehow im-

portant. In MaxDiff, the participants have to choose

the most and least important items out of a set of at-

tributes. Also, response-biases, like e.g., the acqui-

escence bias, extreme responding, or social desirabil-

ity, are eliminated while ratio-scaled results are ob-

tained. Especially for AAL MaxDiff is interesting, as

the task to choose best and worst out of a few items is

easier to use for participants than e.g., the ranking of

multiple items or a choice-based conjoint were partic-

ipants have to consider several attributes with differ-

ing levels (Sawtooth, 2008). Thus, the cognitive effort

for answering is lower and the method is suitable for

older participants.

In total, nine system characteristics were evalu-

ated for their importance for the participant’s privacy

when using an AAL system (cf. Table 1). For this

questionnaire, the comprehensibility and ease of use

for the participants was foreground. Therefore, the

attributes were presented in simple language. Also,

we used examples and symbols for better compre-

hensibility of the attributes. An experimental design

was chosen, in which the participants were presented

with four system characteristics each time (cf. Fig-

ure 1) and six of these choice tasks were conducted

in order not to fatigue the participants. Six different

questionnaire versions were produced. All in all, the

frequency and positional balance of the experimen-

tal design was optimal (each item appeared 16 times

and appeared four times as first and four times as last

in the presented list). The orthogonality of the de-

sign was not optimal, but satisfactory (each items was

paired with the other items between five and seven

times).

2.3 The Statistical Analysis

The MaxDiff is analysed using hierarchical Bayes es-

timation to compute individual-level weights (multi-

nomial logit). The resulting probabilities range from

Privacy Perceptions in Ambient Assisted Living

207

Table 1: Instructions of the technology characteristics in the

questionnaire for the MaxDiff tasks.

factor instruction in the questionnaire

data

recipients who can view the data

automatic whether emergency calls

decisions can be made automatically

by the system

data

granularity how data can be accessed

(e.g. live data, summaries only)

controllability

options to switch the system

or functions off

monitored which activities are monitored

activities (e.g., falls, position, medication)

prominence prominence of the system

sensor types

which types of sensors are used

sensor

location where sensors are installed

reliability reliability of the technology

(e.g., no false alarms)

Figure 1: Examplary MaxDiff tasks with ”most important”

option to the left and ”least important” option to the right.

1 to 100 and are ratio-scaled. Thus, an item with a

score of 20 is twice as preferred as an item with a

score of 10. Still, these relevance scores are relative as

they result in a comparison to the other attributes. No

absolute evaluation of their importance results from

the MaxDiff analysis. Additionally, the results of the

counts analysis are reported, which present the pro-

portion that an item was chosen best, or worst, re-

spectively, when it was included in the presented set

of items (Orme, 2009).

3 THE SAMPLE

The questionnaire was distributed online and in paper-

and-pencil form to the participants, who were re-

cruited with a snowball sampling from the authors’

social contacts as well as online discussion forums for

older adults with dementia and their informal care-

givers. The aim of this sampling method was to reach

a wide range of participants with experience with care

and dementia and from different sociodemographic

groups. A scenario-based approach was used to ac-

count for the sample of users not living with dementia.

125 participants started the questionnaire, of which n

= 86 (68.8%) completed it. The participants were be-

tween 19 and 88 years old (M = 46.75, SD = 20.3),

with 50% older than 50 years, and 58.8% women. All

levels of education were present in the sample (com-

pulsory basic secondary schooling: 4%, secondary

education: 13%, apprenticeship: 26%, university en-

trance diploma: 50%, university degree: 6%; no

diploma: 1%). All participants are from Germany or

Austria. Regarding the participants experiences with

elderly care, 20.9% have already nursed an elderly

relative, 92% of the participants have experienced that

a close relative was in need for care, and 73.2% state

that they have experienced “how dementia affects the

lives of the patients and their relatives”.

4 RESULTS

4.1 General Evaluation

In Figure 2, the mean evaluations of the benefits and

use intentions are depicted. In general, the system was

evaluated positively. AAL technologies are perceived

as useful (M = 0.50, SD = 0.55, min = −1, max = 1),

beneficial (M = 0.42, SD = 0.52), relieving (M =

0.44, SD = 0.51), and comfortable (M = 0.29, SD =

0.51). The only attribute that the participants do not

agree to is that the system ‘brings them closer to peo-

ple’ (M = −0.06, SD = 0.58). In line with the positive

benefit evaluation, the use intention is generally high

(M = 0.38, SD = .44, min = −1, max = 1). 84.8% of

the participants reported a (rather) positive attitude to-

wards the potential use of an AAL system in case of

dementia.

4.2 Privacy Concerns

The participants rated five concerns regarding their

privacy, that have been mentioned in preliminary fo-

cus group sessions. Misuse of data is the most preva-

lent concern for the participants 3, but is only rather

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

208

Figure 2: Benefit evaluation and use intention, n = 86.

Figure 3: Mean rating of the concerns, n = 86.

agreed on (M = 3.76, SD = 1.4, min = 1, max = 6).

Feelings of surveillance (M = 3.7, SD = 1.3) and ob-

trusiveness of the technology (M = 3.64, SD = 1.3)

are additional concerns, that the participants rather

agree on. That they are worried about reaction of

family and friends is slightly denied (M = 3.43, SD =

1.3). Concerns about automatic decisions that the

system makes about the users are rejected (M =

2.51, SD = 1.2). The perception of privacy concerns

is moderately correlated with the disposition to value

privacy (r = .57, p < .01), but not to the other user

factors.

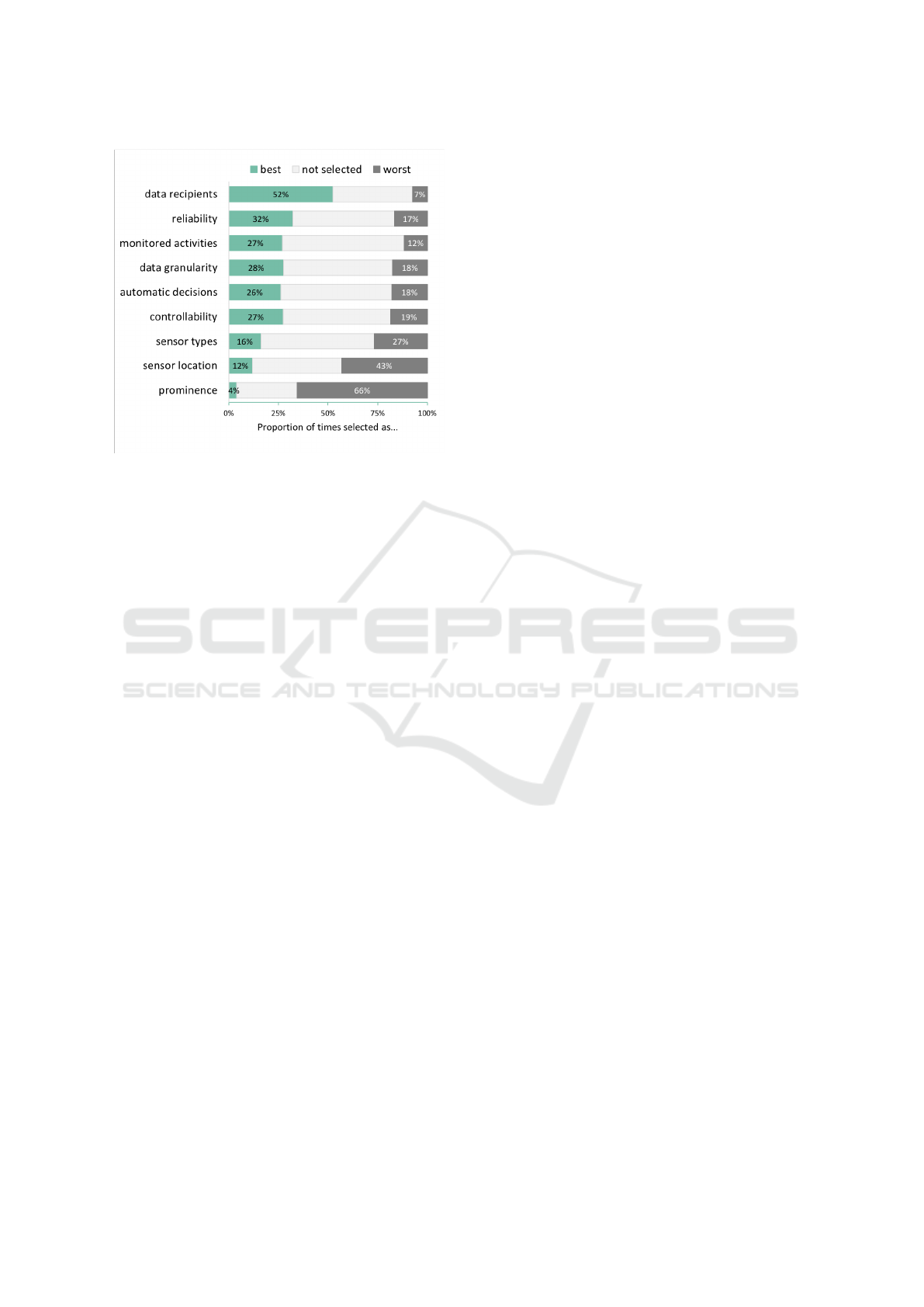

4.3 MaxDiff

In MaxDiff tasks, the participants were presented with

four out of nine system characteristics and evaluated

which is the most and which is the least important for

their privacy when using an AAL system. Figure 4

shows the resulting relevance scores from the hierar-

chical Bayes analysis.

By far the most important system characteristic

for ones privacy is who has access to the data (data

recipient: 21.0). Least important is the prominence

of the technology (1.3) followed by the sensor loca-

tion (4.8) and the sensor types (7.1). The results in-

Figure 4: Relevance of the system characteristics for the

users’ privacy, n = 86.

dicate that the control over the data recipients (21.0)

is three times as important as are the type of sensors

used (7.1). What is monitored by these sensors (mon-

itored activities: 13.4) is than again almost double as

important as the type of sensor itself.

Reliability, monitored activities, data granularity,

automatic decisions, and controllability are on aver-

age quite similarly important to the participants. Ex-

amining the counts analysis (cf., Figure 5), we see

that here the participants strongly differ in their eval-

uation. These medium important five attributes are

almost as often selected as least important as they are

selected as most important.

The count analysis mirrors the results of the hi-

erarchical Bayes analysis: especially prominence has

been often (66% of times shown) selected as least im-

portant. Who has access to the data (data recipients)

was more than half of the times selected as most im-

portant, again stressing its relevance.

5 DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

Privacy concerns represent one decisive obstacle to

the acceptance of AAL technologies by the potential

users, and correspondingly, to their widespread use

(Peek et al., 2014; Yusif et al., 2016). In this study,

privacy concerns regarding AAL technologies were

examined in detail. In focus lies the research question

how characteristics of AAL technologies and systems

influence privacy perceptions. The relevance of these

characteristics is weighted using a Maximum Differ-

ence Scaling (MaxDiff) approach. For that, 86 partic-

Privacy Perceptions in Ambient Assisted Living

209

Figure 5: Proportion of characteristics being selected as

best, worst, or not selected from the times shown, n = 86.

ipants of all age groups evaluated AAL technologies

in a paper-and-pencil or online questionnaire.

The most prevalent privacy concern is the misuse

of data, but also concerns about feelings of surveil-

lance and obtrusiveness of the technology exist. The

only concern that is clearly denied by the participants

is that they worry about automatic decisions the AAL

technologies make about them.

The results of the MaxDiff analysis show clearly

that the data recipient (who has access to the data)

is the most important system characteristic regard-

ing privacy. Users want to decide who they entrust

their data. Additional important influences constitute

the sensitivity of the data which is monitored and ac-

cessed (monitored activities, data granularity), thus

corresponding to the concern of data misuse. But also

the obtrusiveness within the home environment (reli-

ability), psychological privacy (automatic decisions),

and control over the system as a whole are important,

revealing that a sole focus on informational privacy is

too limiting regarding AAL.

The core element of privacy is control. Users

want to decide on their own what data is analysed

and to whom it is transmitted and how. Therefore,

they should be given the choice to whom data and

emergency calls are transmitted as well as in what

granularity and which data. As users trade off the

usefulness of a technology and also of single func-

tions with the perceived (privacy) barriers – the pri-

vacy calculus – it is important to provide them with

control over the technology so that they can choose

which functions to use in what way. Particularly, it

has been shown that the need for technological sup-

port is an important counterweight to concerns (Peek

et al., 2014). This suggests that ‘modular’ AAL sys-

tems should be developed, in which functions may be

switched off until the user decides that this function

is now needed. In this case, the increased need for

the technology and the corresponding higher useful-

ness would after some time override privacy concerns

when ageing processes advance. Modular AAL tech-

nologies show the additional advantage that the users

can get used to the technology and the interaction with

it before ageing process increase difficulties in inter-

acting with and learning of new devices.

Our results indicate to another important aspect:

privacy perceptions are individual. User diversity

adds another layer of complexity for the acceptance

of AAL. More research is needed to identify user

groups that show similar attitudes towards AAL, e.g.,

similar privacy preferences, perception of usefulness,

need for technology, abilities in interacting with tech-

nologies. Technology should be developed that is

adapted to the specific needs of each user groups.

Here again, modular AAL systems can be a useful ap-

proach. Users should be able to pick those functions

and interaction options they prefer.

That the data recipient has the strongest influence

on the privacy perception is only the first step to com-

prehend privacy attitudes in AAL. Next, it is impor-

tant to examine which data recipients are most ac-

cepted, and the same for the levels of the other im-

portant system attributes, e.g., which monitored activ-

ities are accepted, which data granularity is accepted.

Here, the question arises, whether these can be ex-

amined separately or whether they should again be

examined in combination with each other, e.g., in

conjoint approaches. Maybe, the accepted level of

data granularity differ dependent on the data recipient

and what activities are monitored. Conjoint analysis

would offer the opportunity to study a limited num-

ber of attributes in cohesion, illustrating the trade-

offs between these factors. Correspondingly, the re-

sult would be more realistic and thus valid in contrast

to approaches evaluating each attribute in separation.

Moreover, also privacy perception should not be

examined only separately, but the trade-offs between

usefulness, need for technology, and privacy concerns

are important (Peek et al., 2014). For example, it

could be that the data recipient which is seen as most

critical can contribute the most effective help in emer-

gency. The user may still decide to disclose the data

to this recipient because the usefulness of the data dis-

closure outweighs the privacy concerns. These trade-

offs and the privacy calculus is important in explain-

ing user decisions and behaviours.

Despite the interesting insights into privacy pref-

erences by potential users of AAL, some methodolog-

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

210

ical limitations have to be considered when discussing

our results. The sample was quite small, especially

to examine influences of user factors on the attitudes

and perceptions. With a larger sample, cluster analy-

sis approaches could provide more insights into user

group specific preferences for privacy. That the sam-

ple included people of all ages can at the same time

be seen as strength and weakness. On the one hand,

it allowed for the analysis of age effects, but on the

other hand, AAL technologies are targeted to older

adults and their specific needs so that evaluations by

younger adults are of limited relevance and validity.

Solely empathising with the situation and needs of

older adults is not the same as being in this situation.

A drawback of the questionnaire approach is the

missing hands-on experience with the presented tech-

nologies. In spite of all attempts to provide a most

comprehensible technology presentation, the partic-

ipants had only limited information about the AAL

technologies and no option to ask questions.

The questionnaire was distributed in Germany,

correspondingly providing only a German view on

privacy perceptions. Previous studies have shown that

attitudes towards AAL as well as privacy perceptions

are culturally biased (Alag

¨

oz et al., 2011; Krasnova

and Veltri, 2010). On social network sites, Germans

have been shown to expect more damage and perceive

higher risks for their privacy than Americans (Kras-

nova and Veltri, 2010). In contrast, in a comparison

of the attitudes towards AAL between Turkish, Pol-

ish, and German participants, Germans showed the

lowest level of concern (Alag

¨

oz et al., 2011). Demo-

graphic developments challenge not only the German

health care system and society, correspondingly AAL

technology acceptance should be studied in other cul-

tures as well.

REFERENCES

Alag

¨

oz, F., Ziefle, M., Wilkowska, W., and Valdez, A. C.

(2011). Openness to accept medical technology - A

cultural view. Lecture Notes in Computer Science

(including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intel-

ligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 7058

LNCS:151–170.

Anderson, C. L. and Agarwal, R. (2011). The Digitization

of Healthcare: Boundary Risks, Emotion, and Con-

sumer Willingness to Disclose Personal Health Infor-

mation. Information Systems Research, 22(3):469–

490.

Bergstr

¨

om, A. (2015). Online Privacy Concerns: A Broad

Approach to Understanding the Concerns of Different

Groups for Different Uses. Computers in Human Be-

havior, 53:419–426.

Blackman, S., Matlo, C., Bobrovitskiy, C., Waldoch, A.,

Fang, M. L., Jackson, P., Mihailidis, A., Nyg

˚

ard, L.,

Astell, A., and Sixsmith, A. (2016). Ambient Assisted

Living Technologies for Aging Well: A Scoping Re-

view. Journal of Intelligent Systems, 25(1):55–69.

Boise, L., Wild, K., Mattek, N., Ruhl, M., Dodge, H. H.,

and Kaye, J. (2013). Willingness of older adults

to share data and privacy concerns after exposure

to unobtrusive home monitoring. Gerontechnology,

11(3):428–435.

Burgoon, J. K. (1982). Privacy and Communication. An-

nals of the International Communication Association,

6(1):206–249.

Courtney, K. L. (2008). Privacy and SeniorWillingness to

Adopt Smart Home Information Technology in Resi-

dential Care Facilities. MethodsInf, 47:76–81.

Deutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft e.V. (2016). Das Wichtig-

ste 1: Die H

¨

aufigkeit von Demenzerkrankungen.

Deutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft, Infoblatt 1. Tech-

nical report.

Dupuy, L., Froger, C., Consel, C., and Sauz

´

eon, H. (2017).

Everyday functioning benefits from an assisted liv-

ing platform amongst frail older adults and their care-

givers. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9(SEP):1–

12.

Garg, V., Camp, L. J., Lorenzen-Huber, L., Shankar, K.,

and Connelly, K. (2014). Privacy concerns in as-

sisted living technologies. Annales des Telecommu-

nications/Annals of Telecommunications, 69(1-2):75–

88.

Hallewell Haslwanter, J. D. and Fitzpatrick, G. (2016). Why

do few assistive technology systems make it to mar-

ket? The case of the HandyHelper project. Universal

Access in the Information Society, 16(3):1–19.

Heart, T. and Kalderon, E. (2013). Older adults: Are they

ready to adopt health-related ICT? International Jour-

nal of Medical Informatics, 82(11):e209–e231.

Himmel, S. and Ziefle, M. (2016). Smart Home Medical

Technologies: Users’ Requirements for Conditional

Acceptance. I-Com. Journal of Interactive Media,

15(1):39–50.

Jakobs, E., Lehnen, K., and Ziefle, M. (2008). Alter und

Technik. Studie zu Technikkonzepten, Techniknutzung

und Technikbewertung

¨

alterer Menschen [Age and

Technology. Study regarding concepts, use, and eval-

uation of technology by older people]. Apprimus Ver-

lag, Aachen.

Jennings, L. A., Reuben, D. B., Evertson, L. C., Serrano,

K. S., Ercoli, L., Grill, J., and Chodosh, J. (2016). Un-

met Needs of Caregivers of Patients Referred to a De-

mentia Care Program. J Am Geriatr Soc, 63(2):282–

289.

Kirchbuchner, F., Grosse-Puppendahl, T., Hastall, M. R.,

Distler, M., and Kuijper, A. (2015). Ambient intelli-

gence from senior citizens’ perspectives: Understand-

ing privacy concerns, technology acceptance, and ex-

pectations. In De Ruyter, B., Kameas, A., Chatzimi-

sios, P., and Mavrommati, I., editors, Ambient Intelli-

gence, volume 9425, pages 48–59. Springer Interna-

tional Publishing, Cham.

Privacy Perceptions in Ambient Assisted Living

211

Koops, B.-j., Newell, B. C., Timan, T., Skorvanek, I.,

Chokrevski, T., and Galic, M. (2017). A Typology

of Privacy. University of Pennsylvanica Journal of In-

ternational Law, 38(2):1–93.

Krasnova, H. and Veltri, N. F. (2010). Privacy Calculus

on Social Networking Sites: Explorative Evidence

from Germany and USA. Proceedings of the Annual

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

pages 1–10.

Legris, P., Ingham, J., and Collerette, P. (2003). Why do

people use information technology? A critical review

of the technology acceptance model. Information &

Management, 40(3):191–204.

Li, Y. (2014). A Multi-Level Model of Individual Informa-

tion Privacy Beliefs. Electronic Commerce Research

and Applications, 13(1):32–44.

Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda,

S. G., Huntley, J., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee,

S., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., et al. (2017). De-

mentia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet,

390(10113):2673–2734.

Mortenson, W. B., Sixsmith, A., and Beringer, R. (2016).

No Place Like Home? Surveillance and What Home

Means in Old Age. Canadian Journal on Aging,

35(1):103–114.

Nissenbaum, H. (2010). Privacy in Context: Technology,

Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life. Stanford Uni-

versity Press, Stanford, California.

Orme, B. (2009). Sawtooth Software MaxDiff Analysis

: Simple Counting, Individual-Level Logit, and HB.

Sawtooth Software Research Paper Series.

Peek, S. T. M., Wouters, E. J. M., van Hoof, J., Luijkx,

K. G., Boeije, H. R., and Vrijhoef, H. J. M. (2014).

Factors influencing acceptance of technology for ag-

ing in place: A systematic review.

Rashid, U., Schmidtke, H., and Woo, W. (2007). Man-

aging Disclosure of Personal Health Information in

Smart Home Healthcare. Universal Access in Human-

Computer Interaction. Ambient Interaction, pages

188–197.

Sackmann, R. and Winkler, O. (2013). Technology gener-

ations revisited: The internet generation. Gerontech-

nology, 11(4):493–503.

Sawtooth (2008). MaxDiff System. Design, 98382(360):0–

26.

Schomakers, E.-M., van Heek, J., and Ziefle, M. (2018). A

Game of Wants and Needs. The Playful, user-centered

assessment of AAL technology acceptance. In Pro-

ceedings of the 4th International Conference on In-

formation and Communication Technologies for Age-

ing Well and e-Health (ICT4AgeingWell 2018), pages

126–133.

Schomakers, E.-m. and Ziefle, M. (2019). Privacy Con-

cerns and the Acceptance of Technologies for Aging

in Place. In Zhou, J. and Salvendy, G., editors, ITAP

2019. Springer International Publishing.

Strese, H., Seidel, U., Knape, T., and Botthof, A. (2010).

Smart Home in Deutschland. Institut f

¨

ur Innovation

und Technik (iit), 46.

Valdez, A. C. and Ziefle, M. (2018). The users perspec-

tive on the privacy-utility trade-offs in health recom-

mender systems. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies.

van Heek, J., Himmel, S., and Ziefle, M. (2017). Helpful

but Spooky ? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrast-

ing User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care

Needs. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Con-

ference on Information and Communication Technolo-

gies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2017),

pages 78–90.

Westin, A. F. (1967). Privacy and Freedom. American So-

ciological Review, 33(1):173.

Wilkowska, W. and Ziefle, M. (2012). Privacy and data

security in e-health: Requirements from the users per-

spective. Health informatics journal, 18(3):191–201.

Yusif, S., Soar, J., and Hafeez-Baig, A. (2016). Older peo-

ple, assistive technologies, and the barriers to adop-

tion: A systematic review. International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 94:112–116.

Ziefle, M. Z. and Wilkowska, W. (2010). Technology ac-

ceptability for medical assistance. In 4th International

Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for

Healthcare (PervasiveHealth). IEEE.

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

212