Learning from Others’ Mistakes: An Analysis of Cyber-security Incidents

Giovanni Abbiati

1,3

, Silvio Ranise

3

, Antonio Schizzerotto

2,3

and Alberto Siena

3

1

Fondazione Rodolfo Debenedetti, Milan, Italy

2

University of Trento, Trento, Italy

3

Fondazione Bruno Kessler, Trento, Italy

Keywords:

Cybersecurity, Data Analytics.

Abstract:

Cyber security incidents can have dramatic economic, social and institutional impact. The task of providing an

adequate cyber-security posture to companies and organisations is far far from trivial and need the collection

of information about threats from a wide range of sources. One such a source is history in the form of datasets

containing information about past cyber-security incidents including date, size, type of attacks, and industry

sector. Unfortunately, there are few publicly available datasets of this kind that are of good quality. The paper

reports our initial efforts in building a large datasets of cyber-security incidents that contains around 14,000

entries by merging a collection of four publicly available datasets of different size and provenance. We also

perform an analysis of the combined dataset, discuss our findings, and discuss the limitations of the proposed

approach.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cyber security incidents, such as intentional attacks

or accidental disclosures, can have serious economic,

social and institutional effects. The average total cost

for companies and institutions spans from $7.35 mil-

lions in the U.S. to $1.52 million in Brazil, with a

notable relation between the cost of the data breach

and the number of lost records (Ponemon Institute,

2017). In this context, data about past cyber security

incidents can give an insight on potential vulnerabil-

ities and attack types, thus helping to prevent them,

provided that the data are available and have enough

quality. Commercial reports on security incidents and

data breaches can be easily retrieved; for example,

(statista, 2018) is a well known online service that re-

ports the annual number of data breaches and exposed

records in the U.S. from 2005 to 2018. While these

reports are potentially interesting, the lack of trans-

parency on their generation method, as well as their

(intended) non-academic audience, makes it difficult

to use them in scientific work. On the other hand, aca-

demic works that take a quantitative approach to the

analysis of data breaches are less numerous. In (Ed-

wards et al., 2016), authors analyse data from the Pri-

vacy Rights Clearinghouse (PRC), and draw the con-

clusion that publicly reported data breaches in the

USA have not increased significantly over the past 10

years, either in frequency or in size. (Wheatley et al.,

2016) combined two different datasets, DataLossDB

(currently unmaintained as public dataset) and the

mentioned PRC, finding divergent trends between US

and non-US firms. (Xu et al., 2018) also uses the PRC

dataset to analyse whether the data breaches caused

by cyber attacks are increasing, decreasing, or stabil-

ising. (Romanosky, 2016) reports to have analysed

a commercial dataset of 300,000 observations about

corporate loss events, having extracted a subset of

around 15,000 observations about cybersecurity inci-

dents out of it. As this last work confirms, having ac-

cess to a commercial dataset seems to be a necessity

since publicly available datasets are limited in size (up

to 5,000 events) and this reduces the effectiveness of

several data analysis techniques.

To overcome this data availability limitation, in

this paper we follow the intuition of (Wheatley et al.,

2016), investigating on the possibility to combine

multiple publicly available datasets to obtain a larger

one, capable to support statistically grounded analysis

of security incidents. Specifically, the paper reports

on two main activities. First, we present the under-

taken methodology, highlighting in particular the en-

countered issues, limitations and workarounds. Sec-

ond, we analyse the generated dataset with respect to

the yearly trend, the target business sector, the type

of attack and the magnitude of the attack, with the

Abbiati, G., Ranise, S., Schizzerotto, A. and Siena, A.

Learning from Others’ Mistakes: An Analysis of Cyber-security Incidents.

DOI: 10.5220/0007721202990306

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (IoTBDS 2019), pages 299-306

ISBN: 978-989-758-369-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

299

twofold objective of extracting useful information and

evaluate the methodology used to generate the data.

The paper is structured as follow: Section 2 de-

scribes the methodology undertaken to collect data

and merge them into a single dataset. Section 3

presents the statistical analysis of the generated data

and the produced results. Section 4 discusses the re-

sults with respect to the objectives and concludes the

paper, outlining the future challenges.

2 METHODOLOGY

Information about cyber-security incidents are re-

ported every day on the media, but a systematic access

to the sources is problematic because is distributed

across a large number of websites and is described in

natural language. Fortunately, there are initiatives that

aggregate news about cyber-security incidents from

third party sites as part of a professional work, making

them available on-line as structured datasets. To have

a wider coverage of the incidents’ reports, we further

aggregate four databases into a larger one. However,

the datasets adopt different structures and are based

on different classifications on key variables, such as

the type of attacks or the economic sector of the firms

affected. For this reason, the first step of this work

aimed at developing a method to overcome the tech-

nical and conceptual discrepancies between different

sources. Below, we report our method, which con-

sists of three main steps: Identification and Collection

(Section 2.1); Mapping and Selection (Section 2.2);

and Redundancy Elimination (Section 2.3). We con-

clude (Section 2.4) with a description of the main fea-

tures of the combined dataset.

2.1 Identification and Collection

We consider in particular four datasets of cyber-

security incidents derived from four websites, de-

tailed in Table 1: PRC: Privacy Rights Clearing-

house — a U.S. -based nonprofit organisation for pri-

vacy awareness and protection of individuals, main-

taining a collections of data-breaches. ITRC: The

Identity Theft Resource Center — a U.S.-based non-

profit organisation, whose mission is to help victims

of identity crimes (e.g., identity theft, scams, and

frauds), provides a collection of data-breaches on

yearly basis. BLI: The Data Breach Level Index —

a website sponsored by Gemalto (which also offers

cyber-security solutions), contains datasets of pub-

licly disclosed data-breaches as well as related statis-

tics with graphical representations. IiB: The ‘In-

formation is Beautiful’ website — which offers vi-

sual representation of data about different phenomena

ranging from infectuous diseases to cyber-security in-

cidents.

Looking at column ‘Description’ in Table 1, the

four datasets appear quite heterogeneous. They are

made available in different formats (CSV, PDF or

HTML), the number of categories associated to in-

cidents varies from 6 to 14, the number of incidents

greatly differ—ranging from few hundreds to several

thousands—as well as their time span. . Additional

sources of heterogeneity emerge as soon as we take a

closer look. First, consider column ‘Attack types’ of

Table 1; two observations are in order: (a) PRC, BLI,

and IiB consider several types of attacks while ITRC

focuses just on one type and (b) the three used classi-

fications differ in the number and types of classes of

attacks. Then, consider column ‘Organization types’

of Table 1; the main remark is that PRC and ITRC use

(different) classifications while BLI and IiB does not.

Finally, observe that BLI also contains a classification

of the attackers.

On the other hand, a lesser degree of heterogene-

ity is detectable on other domains, where the fields

present a similar or identical schema or at least some

conceptual similarity. For these reasons, harmonising

them into a single dataset looks challenging but feasi-

ble, and potentially useful.

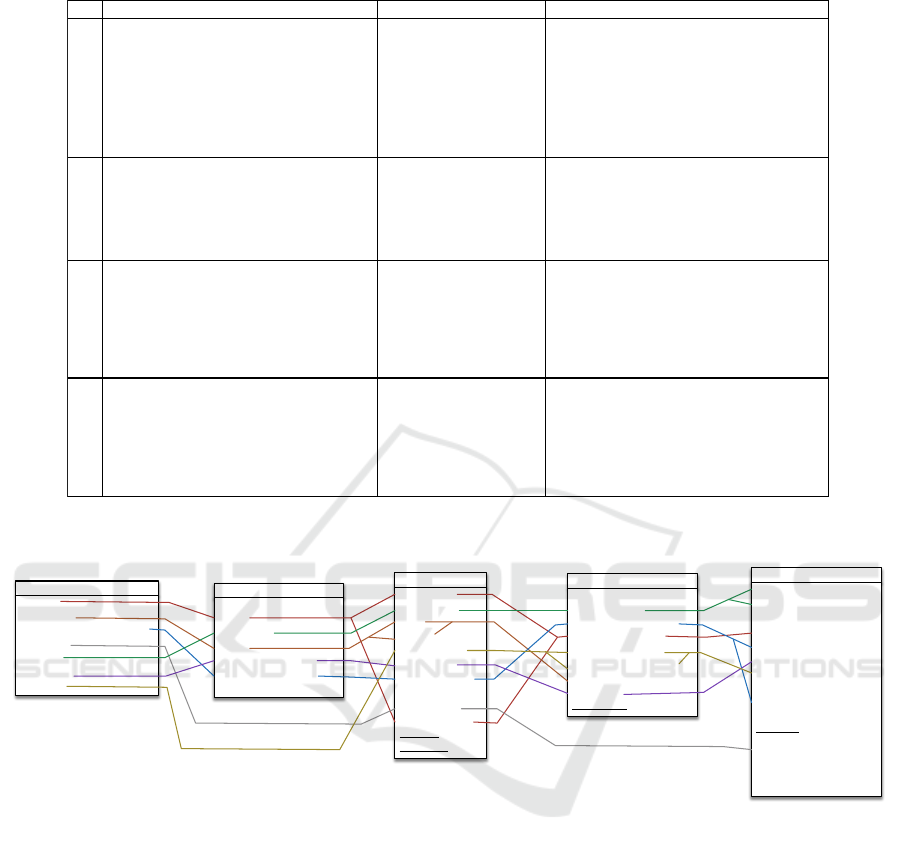

2.2 Mapping and Selection

Given the difference and similarities illustrated above,

we combine the four datasets into a single pool con-

taining all the incidents in each dataset with the fol-

lowing 7 categories: Year; Location; Compromised

Records; Source; Entity; Industry; and Cause. Table 2

shows the mapping from the original categories to the

harmonised ones. On the left-end side, our dataset

schema is reported (“Incident”), while the coloured

lines define the mapping of each field to the source

datasets. As concern the year of the incident, the in-

formation source, the target entity, its location, and

the number of compromised records, the mapping is

straightforward, because the values in such categories

are homogenous across the four datasets,. Much of

the effort is needed to harmonise the type of organisa-

tion (Industry) and the type of attack (Cause). More

precisely, we need to perform the following two activ-

ities (1) mapping the original codings and translating

into two homogeneous classifications and (2) check-

ing the homogeneity of the resulting dataset and se-

lecting one or more sub-sets that show some internal

coherence.

Data Mapping. A critical work has been the rec-

onciliation of the attack types — i.e., the cause

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

300

Table 1: Descrition of the four datasets.

ID

Attack types

Format:

CSV

Number of attributes:

12

Number of entries:

4,413

Time range:

2005-2017

Impact: number of records

Format:

set of PDF files

Number of attributes:

6

Number of entries:

5,924

Time range:

2005-2017

Impact:

number of records

Format:

set of HTML pages

Number of attributes:

9

Number of entries:

7,878

Time range:

2013-2018

Impact:

risk score

Format:

Google sheet

Number of attributes:

14

Number of entries:

292

Time range:

2004-2017

Impact: number of records

Description

Organization types

PRC

www.privacyrights.org/data-breaches

1. Payment Card Fraud

2. Hacking or Malware

3. Insider

4. Physical Loss

5. Portable Device

6. Stationary Device

7. Unintended

Disclosure 8. Unknown

1. Bus.-Financial and Insurance Services

2. Bus.-Other

3. Bus.-Retail/Merchant-Including Online

Retail

4. Educational Institutions

5. Government & Military

6. Healthcare, Med. Providers & Med.

Insurance Services

7. Nonprofits 8. Unknown

BLI

breachlevelindex.com/data-breach-

library

1. Identity Theft

2. Account Access

3. Financial Access

4. Existential Data

5. Nuisance

1. Education

2. Entertainment

3. Financial

4. Government

5. Healthcare

6. Hospitality

7. Industrial

8. Insurance

9. Non-profit

10. Retail

11. Social Media

12. Technology

13. Other

ITRC

www.idtheftcenter.org/data-breaches

1. Identity theft

1. Banking/Credit/Finance

2. Business

3. Educational

4. Government/Military

5. Medical/Healthcare

IiB

informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/

worlds-biggest-data-breaches-hacks

1. accidentally published

2. hacked

3. inside job

4. lost/stolen device or

media

5. poor security

1. academic

2. app

3. energy

4. financial

5. gaming

6. government

7. healthcare

8. legal

9. media

10. military

11. retail

12. tech

13. telecoms

14. transport

15. web

Table 2: Redefinition of the data breach incident report.

breach_ID

year

company

state

breach_category

records_exposed

exposed_record_nr

ITRCIncident

pub_date

company

city

state

attack_type

org_type

total_records

description

source_url

breach_year

latitude

longitude

PRIncident

rank

organization

breached_records

date_od_breach

type_of_breach

source_of_breach

location

industry

risk_score

BLIIncident

entity

alternative_name

story

year

records_lost

organization

method_of_leak

interesting_story

nr_of_stolen_records

data_sensitivity

exclude

1st_source_link

2nd_source_link

3rd_source_link

source_name

IiBIncident

year

location

compromised_records

source

entity

industry

cause

Incident

field. While for some source categories the map-

ping was straightforward (e.g., Inside jobs), others

made it difficult to produce a coherent and shared tax-

onomy of attacks. For example, BLI has two fields,

“Type of breach” and “Source of breach”, which re-

port information about what kind of data has been ac-

cessed (e.g., Financial data, Existential data) and the

source of the breach (e.g., Malicious insider, Hack-

tivist, State sponsored); PRC has a dedicated cate-

gory for payment card frauds, and differentiates var-

ious types of physical losses; ITRC puts in the same

category physical losses and employee errors, while

Improper Disposal is kept separated from an Acciden-

tal disclosure. We ended up with a custom classifica-

tion, which attempts to minimise the number of cat-

egories. Specifically, the following categories have

been identified: (i) two main categories for inten-

tional disclosures: malicious attacks coming form in-

side (Insider job) and from outside (Hacking or Mal-

ware); (ii) one category for unintentional disclosures

(Unintended disclosure); (iii) one category for phys-

ical losses (Lost / Stolen device or media, which can

be hardly differentiated in practice); (iv) one residual

category for other unmapped incidents (Other / Un-

known). Attack types from the source datasets are as-

signed to one of these categories according to a case-

by-case evaluation.

Another field that required reconciliation was the

type of attacked organisation — i.e., the Industry

field. Source datasets classify organisations accord-

ing to differente taxonomies and with different level

of granularity. A complete manual reclassification

was therefore needed. We ended up defining a cus-

tom classification, which tries to optimise the cover-

Learning from Others’ Mistakes: An Analysis of Cyber-security Incidents

301

age and equal distribution of the source categories.

The adopted classification consists in the follow-

ing macro business sectors: (i) Education & Health-

care; (ii) Financial services; (iii) Industrial produc-

tion; (iv) Information & Technology; (v) Standard

commercial activities; (vi) Other privately-held busi-

nesses; (vii) Public administration; (viii) Non-profit;

(ix) Other.

Data Selection. At the end of the data mapping step,

we derived a single dataset containing 16,997 rows.

After an analysis of the entries, it resulted that the

largest number of incidents concerned organisations

or companies located in North America (either USA

or Canada). Specifically, 15,293 incidents occurred

to organisations/companies in North America, corre-

sponding to more than 90% of the total. This is proba-

bly due to two factors: (a) the dataset were taken from

online services located in USA, and (b) these coun-

tries (USA and Canada) are subject to laws and regu-

lations containing mandatory requirements for the no-

tification of security breaches since 2004/2005. We

hence decided to limit our analyses only to incidents

happened in North America.

2.3 Redundacy Elimination

Despite showing some internal coherence, the dataset

obtained after mapping and selection shows some re-

dundancy. There are several sources of redundancy,

that we describe below together with the techniques

that we use to detect and eliminate them.

Duplicated Events. First, redundancy refers to a se-

curity incident reported more than once. Duplicate

cases could be easily removed, but an issue emerges

on the actual definition of “duplicate”. In some cases

two rows reported a security incident in the same

year, concerning the same entity, but only in one case

the number of compromised records was known. A

check on a sample of original incident URL sources

suggested that these instances referred actually to the

same events. Such cases were removed, maintain-

ing the records reporting the number of compromised

records only. The trickiest case referred to records

with similar entity names. Different sources reported

the same incident recording the entity name with dif-

ferent acronyms, shortcuts, legal specifications and

mistakes. We hence identified an additional set of po-

tential duplicates. Here is a list of possible cases:

Differently Decorated Names. Differences could be

related to partial omissions, typically concerning legal

specification (e.g. “Google” and “Google, inc.”). In

this case the two names were unified through a simple

catalog of pattern templates.

Similar Names. A more problematic set of cases

was due to entity names that were actually simi-

lar but no precise detection rule could be defined.

These cases involved typically spelling or punctuation

mistakes (e.g. “HOMECARE OF MID-MISSOURI

INC.” and “HOME CARE OF MID MISSOURI”, or

“COHN HANDLER STURM” and “COHN HAN-

DLES STURM”). These are basically singletons, and

therefore defining pattern matching for all the in-

stances would have resulted in a huge but useless

effort. To overcome this problem, an algorithm has

been applied to spot similar entities.

The algorithm proceeded by comparing all the

possible (n(n − 1))/2 pairs of entities, assigning to

each pair a score, calculated using their Jaro-Winkler

distance. A manual identification of the duplicates

was performed below the threshold of 0.18, a thresh-

old identified after manual tests as the one minimis-

ing both false positives and false negatives.

False Positives. were a major issue in the activ-

ity of similarities identification. Particularly prob-

lematic was the case of entities sharing part of the

name but indicating different institutions (e.g. “Uni-

versity of ...”). This phenomenon had to be con-

trasted with cases of true positives, such as different

branches of a same organisation, such as territorial

units (e.g.“7eleven’ York”, “7eleven Baltimora”).

False Negatives. As for false positives, also false

negatives involve the use of human knowledge and

cannot be easily translated into clear-cut rules. For

example, “Google” and “Alphabet”, in which the lat-

ter is the new corporate name of the first; or “UNI-

VERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES” and

“UCLA”, where the latter is an acronym for the first.

Once the algorithm has generated the list of candi-

date duplicates, a manual pass allowed us to identify

false positives. To deal with them, a further catalogs

of patterns have been defined, a white list, listing can-

didate duplicates. More difficult was to deal with false

negatives. So far, they are added to a third pattern cat-

alog, the black list, whenever they are identified.

Legal Entities. A last issue concern the legal set-

ting of reported entities. Companies and public ad-

ministrations can be articulated in hierarchies of con-

trolled companies. Controlled companies can have le-

gal personality, and therefore their own name, which

in some cases may differ completely from the origi-

nal. If the same security breach is reported multiple

times and using different names (of the controller and

controlled company), this is not easily identifiable in

an automatic way.

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

302

2.4 Merged Dataset

The merged dataset, as resulting from the described

process, contains 14.820 entries. We can not claim

that it is fully duplicate-free, but duplicates also ex-

isted in the source datasets, accounting for around 7%

of the total, on average, and this makes our work com-

parable with the literature. We also inherit other as-

pects of the source datasets: firstly, the dataset con-

tains only attacks reported to authorities, which do

not include foiled or unreported attacks; secondly,

there are many salient information (such as technolo-

gies used by firms and public administration depart-

ments) about which nothing is known. Finally, our

mapping of categories of attacks and organisation re-

mains somehow arbitrary, but unfortunately arbitrari-

ness also affects the source dataset, as none of the

publisher adopted an official classification, assigning

rather their own.

3 DATA ANALYSIS

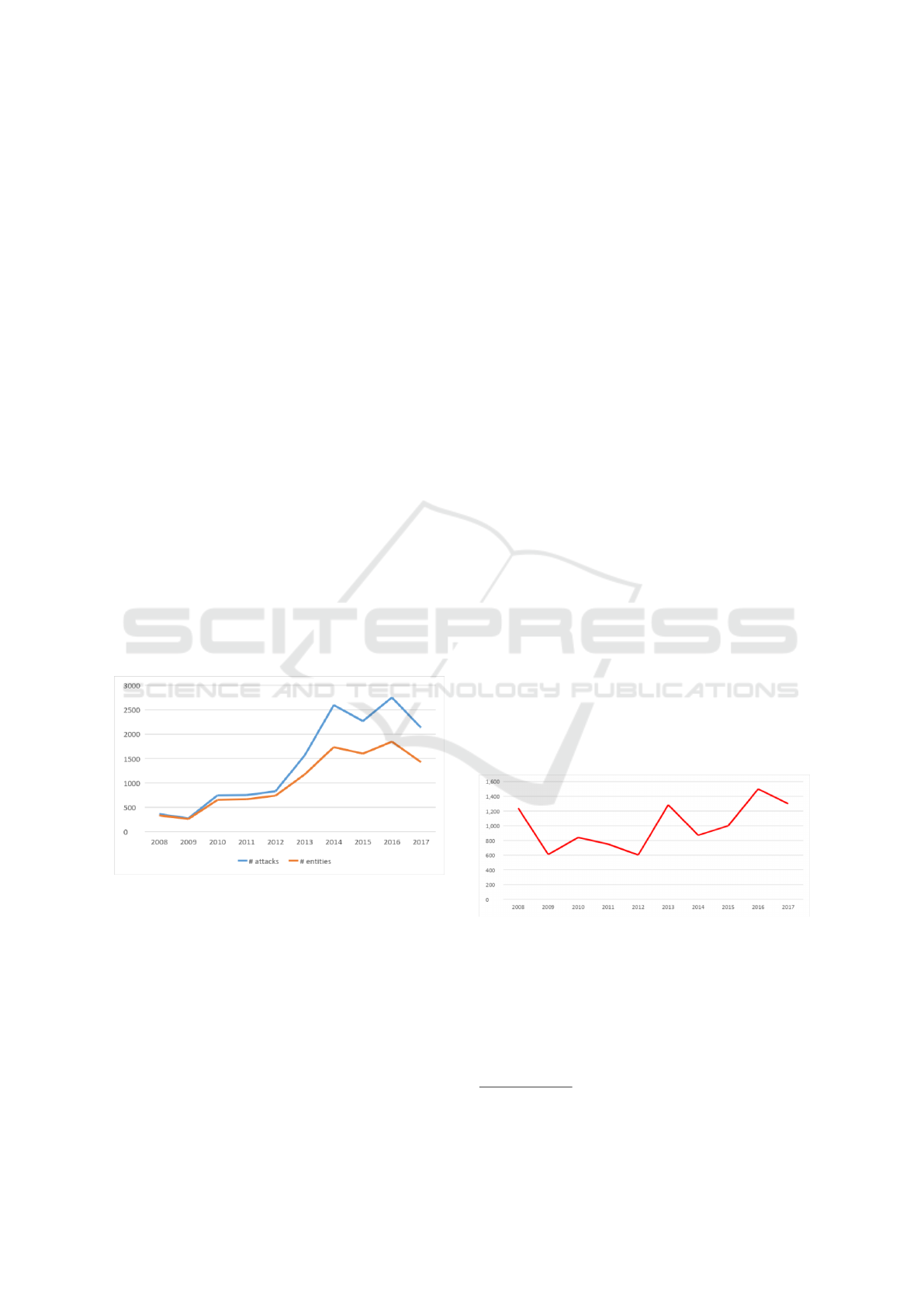

We start our preliminary inspection of the data by

plotting the trends of the number of cyber attacks,

the number of firms involved and a measure of the

damage they caused over the period 2008-2017 (Fig-

ures 1-2).

Figure 1: Yearly reported number of cyber attacks and enti-

ties involved - 2008/2017.

As Figure 1 shows, the reported number of attacks

constantly increased from 2008 onwards. The num-

ber almost tripled from 2009 to 2010 passing from

275 to 746 events and, after two years of relative sta-

bility, sharply increased again from 2012 to 2013, and

since then remained stable. As concern the number of

entities subject to attacks, we can observe that from

2012 onwards their number is steadily lower than the

number of attacks, indicating that a significant frac-

tion of entities received multiple attacks in the same

year. Figure 2 reports, for the same time-span, the

median number of compromised records. In this case

there is no clear-cut trend as in Figure 1. However, it

is worth noticing that the last three years rank among

the highest of the period considered. This evidence

contradicts the optimistic forecasts produced by the

predictive model of (Edwards et al., 2016), according

to which we should have observed a reduction in the

level of damage caused by the attacks, both in median

terms and considering extreme events.

The figure also shows that cyber-attacks can be ex-

tremely harmful for private and public organisations:

the median number of compromised records varies

from 600 up to over 1,400.

The following tables break down the information

on the number of attacks by year and sector (Ta-

ble 3) and their relative significance (Table 4). Ac-

cording to Table 3), the sector mostly damaged by

cyber-attackers is health and education (45%). Sec-

tors such as public administration, financial services,

standard commercial activities account for 11-13% of

reported attacks each. At the bottom of the ranking

stand information and technology (5.5%), industrial

production (0.9%) and no-profit (0.8%). For a resid-

ual 10% of attacks the activity sector was not coded

in the original source. The ranking depicted above

is constantly evolving: health and educational orga-

nizations’ quota is decreasing from the period 2010-

2012 (values around 55%) to the 36.6% registered in

2017. The same relative reduction is found for public

administration, whose quota decreased steadily from

20% (in 2008) to today’s 6%. Conversely, the sec-

tors of finance, industrial production, information and

technology and standard commercial activities see for

the same period an increasing trend.

Figure 2: Median yearly number of compromised records -

2008/2017.

These figures alone, though, cannot provide a

meaningful picture of the exposure of activities to

cyber-attacks. For this reason we calculated the odds

of being target of a cyber attack by sector and year.

Odds ratios describe the relative risk of being attacked

in relations to the sector in which the firm operates.

1

1

Odds are computed by dividing the proportion of year-

by-sector firms attacked by the corresponding proportion of

Learning from Others’ Mistakes: An Analysis of Cyber-security Incidents

303

The situation is depicted in Table 4. Industry and

other commercial activities have a very low incidence

rate all throughout the period, probably given the

small relevance of personal data storage in their activ-

ity. Health and education firms show a very high but

declining trend in the odds of being attacked, passing

from a high value of 5.7 to 4.1. As predictable, finan-

cial services are a relatively common target for cyber-

attackers (odds ratios around 3/4 for all the period

considered), as well as information and technology,

whose odds of being attacked skyrocketed since 2013.

Table 3: Attack by year and sector. Percentages.

!"#$

%&'()*$+#,-

.$/'(0*+/&

%&1/$2#*+/

&-#&'-

*"03&/,/45

6+&#&0+#,-

)"$7+0")

8'(0#*+/&-

9-

:"#,*30#$"

;*3"$-

0/22"$0+#

,-#0*+7+*+")

<&'"1+&"'-

.$+7#*",5=

3",'

>(?,+0-

#'2+&+)*$#

*+/&

@/&=.$/1+*

<&A&/B&

C/*#,

DEEF

0.0 0.6 12.2 43.6 8.1 0.0 20.3 0.3 15.0 GEE

DEEH

0.0 1.8 9.5 50.9 4.7 0.0 19.6 0.0 13.5 GEE

DEGE

0.0 0.7 13.1 55.1 11.4 0.0 13.7 0.0 6.0 GEE

DEGG

0.0 0.8 7.1 56.9 11.1 0.0 11.7 0.4 12.1 GEE

DEGD

0.1 1.7 8.7 54.3 12.6 0.0 10.8 2.4 9.4 GEE

DEGI

0.1 6.1 12.2 48.2 10.9 0.0 11.1 0.5 11.1 GEE

DEGJ

0.0 4.5 11.1 53.3 10.9 2.5 11.7 0.2 5.7 GEE

DEGK

0.0 5.5 15.3 37.1 13.9 5.8 12.2 0.1 10.1 GEE

DEGL

1.8 9.1 13.4 40.0 15.6 4.3 9.5 1. 5 4.8 GEE

DEGM

3.8 7.6 15.1 36.6 16.1 10.7 5.7 1.7 2.8 GEE

C/*#, ENH KNK GDNM JKNG GINE INF GENF ENF MNJ GEE

Table 4: Relative risk for a firm of being attacked, by sector.

YEAR

Industrial/

production

Information/

and/technology

Financial/

services

Education/&/

Healthcare

Other/

commercial/

activities

2008 0.0 0.3 4.5 5.7 0.2

2009 0.0 0.9 3.4 6.2 0.1

2010 0.0 0.3 4.1 5.3 0.2

2011 0.0 0.2 2.3 5.9 0.2

2012 0.0 0.4 3.0 5.4 0.3

2013 0.0 2.3 3.5 5.0 0.2

2014 0.0 1.9 3.2 5.3 0.2

2015 0.0 2.4 4.6 4.4 0.3

2016 0.1 3.3 3.9 4.3 0.3

2017 0.2 2.7 4.1 4.1 0.3

Table 5 illustrates the attacks by type. The trends

depicted show the rapidly changing geography of the

way cyber-attacks are conducted: an increasing ma-

jority of attacks are conducted via hacking and mal-

ware, along with the diffusion of online tools to work

and store data. At the same time, all other attack

types are losing importance: stolen devices or media

pass from 48.9% in 2008 to a residual 1.5%; inside

active firms in USA. Values equal to 1 mean that exposure is

in line with the sector size; values greater than 1 mean over-

exposure; values comprised from 0 to 1 mean the contrary.

Table 5: Type of attack by year (percentage).

Year

Hacking+

or+

Malware

Inside+job

Stolen+

device+or+

media

Poor+

security

Unintend

ed+

disclosur

Other+/+

Unknown

Total

2008

16.1 8.6 48.9 0.0 22.5 3.9 100

2009

19.3 10.9 46.9 0.0 19.3 3.6 100

2010

14.9 13.1 52.4 0.0 13.9 5.6 100

2011

21.8 12.3 45.5 0.3 14.4 5.7 100

2012

30.1 10.8 38.5 0.0 15.3 5.3 100

2013

44.3 15.3 15.3 0.1 21.3 3.6 100

2014

41.1 11.2 6.7 0.1 17.2 23.8 100

2015

45.1 9.6 4.0 0.1 16.3 24.9 100

2016

50.0 5.1 2.9 0.0 13.7 28.2 100

2017

42.5 4.0 1.5 0.1 9.2 42.9 100

Total 39.9 9.2 13.8 0.1 15.4 21.6 100

jobs and unintended disclosure show a similar, even

though less spectacular, decrease, both falling under

10% during the last year. The “other /unknown” cat-

egory is currently the modal one and we conjecture

that this data has two different explanations: the first

refers to the ability of cyber attackers. The smoother

is the attack, the more difficult it is to identify, and

then report, its actual cause. The second one refers

to the quality of the data. A part of it may be in fact

attributable to sloppiness in reporting the attacks. We

have indirect evidence of it when cross-tabulating the

sector with the type of attack (Table 6): the rising cat-

egory “undefined privately held businesses” (perhaps

another example of sloppiness) is the one for which

most of the attacks are of unknown origin. As con-

cern the rest of the sectors, it is interesting to notice

how hacking and malware represents by far the main

problem in all the sectors except from health and

education, where unintended disclosure and stolen

devices are a big issue, and public administration,

which sees various sources of attacks.

Table 6: Type of attack by sector (percentage).

Sector/Type+of+attack

Hacking+or+

Malware

Inside+job

Stolen+

device+or+

media

Poor+

security

Unintende

d+

disclosure

Other+/+

Unknown

Total

Industrial+production

53.4 3.0 0.8 0.8 3.8 38.4 100

Information+and+Technology

65.5

2.7 0.5 0.3 10.3 20.8 100

Financial+services

41.8 10.1 7.7 0.0 14.4 26.1 100

Education+&+Healthcare

32.2 9.7 22.3 0.1 18.3 17.5 100

Other+commercial+activities

59.5

8.5 4.5 0.0 7.0 20.5 100

Undefined+privately-held+businesses

2.2

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.2 97.6 100

Public+administration

29.4 14.2 11.0 0.1 25.9 19.3 100

Non-profit

51.3 5.0 10.1 0.0 6.7 26.9 100

Unknown+

62.5 9.6 12.4 0.0 12.5 3.1 100

Total 39.9 9.2 13.8 0.1 15.4 21.6 100

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

304

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

The paper reports our initial efforts in building a large

dataset of cyber-security incidents by merging a col-

lection of four publicly available datasets of different

size and provenance, overcoming the lack of publicly

available datasets of substantial size observed in pre-

vious research (Romanosky, 2016).

By analysing the resulting dataset with standard

statistical techniques, our work confirms the gener-

ally observed rapidity with which the phenomenon

of cyber-attacks is evolving. While incidents caused

by malicious outsiders passed from 16% to 50% in

a time-span of just five years, other leading causes

of data breaches such as malicious insiders and un-

intended disclosures lost most of their importance in

the same period. There may be multiple causes un-

derlying this trend. On the one hand, the decreasing

relevance of unintended disclosures and malicious in-

siders may be the result of the adoption of better se-

curity procedures and awareness programs by compa-

nies and organisations. On the other hand, remote at-

tacks are more and more widespread because of the

explosion of personal and sensitive data available on-

line resulting from the digitalisation of many aspects

of our lives. These factors seem to confirm the idea

that organisations and companies should take a holis-

tic approach and tune their cyber-security postures ac-

cording to a variety of sources about threats and coun-

termeasures including cyber-intelligence information

about current threats provided by, e.g., national or

international Computer Emergency Response Teams

(CERTs). It is thus not surprising that the forecasts

about the size of 2015 and 2016 data breaches con-

tained in (Edwards et al., 2016) remain partly un-

achieved.

Concerning the limitations of our approach, two

issues must be considered. The first is related to the

coverage of data and is shared with previous work

(e.g., (Romanosky, 2016)). Since the four datasets

used to build ours are based on public notifications to

authorities, it is unclear whether the data are repre-

sentative of the overall phenomenon of cyber-attacks

or not. We draw this consideration from the compari-

son of two figures. In our dataset, the share of private

USA companies and organisations involved in secu-

rity breaches amounts to minuscule figures, namely

0.02% (or less) per year. An official report based on

a representative UK sample highlights that 67% of

medium-large firms have suffered from cyber-attacks

in 2016 (Klahr et al., 2017). The corresponding num-

ber for Italy in the same period, based on another na-

tional representative survey, is 43% (Biancotti, 2017).

We are currently gathering additional sources of in-

formation to understand to what extent our analyses

reflects actual trends operating in the overall popu-

lation of US firms and organization. The second is-

sue to be considered is the remarkable amount of ef-

fort required to make the merged dataset coherent and

uniform. The result is apparently worth the effort; a

database derived from publicly available information

that is comparable in size to that used in (Romanosky,

2016), which is privately owned and contains around

15,000 descriptions of data breaches. However, we

acknowledge that the relevance of the results depends

on the quality of the generated dataset, which in turn

depends on the quality of the method used to join

the source datasets: it must be able to eliminate re-

dundancies and consistently map the source categori-

sations into one which is general enough to accom-

modate those used in the initial datasets and—at the

same time—not too coarse to loose precision and sig-

nificance in the analysis phase. To tackle this issue,

our future efforts will be devoted to reach a high-level

of automation of the various steps of the methodol-

ogy by developing a toolkit for automatically collect-

ing, tidying, mapping, and merging datasets of cyber-

security incidents. The main benefit of developing

such a toolkit is flexibility along two dimensions.

First, it will be possible to experiment with different

taxonomies for the types of attacks and economic sec-

tors to better identify which option minimises the loss

of precision and coherence when merging different

datasets. Ultimately, this would reduce the level of ar-

bitrariness in the data manipulations besides those im-

posed by the publishers of the original datasets. The

second dimension is a tighter integration with the data

analysis phase: depending on the results of the latter,

we can decide to investigate some features of the com-

ponent datasets and use the results to fine-tune some

aspects of the collection, selection, mapping, and re-

dundancy elimination steps. The flexibility deriving

from a high-level degree of automation of the method-

ology will also simplify the inclusion of new datasets,

increase the size of the merged dataset, and possibly

make the application of a wider range of data analy-

sis techniques.

The present work has revealed some preliminary

results and interesting potentialities, but it has also

highlighted issues and limitations. This raises an im-

portant observation. As stated in Section 1, several

surveys and statistical reports are available online,

mostly from private companies. Since the issues we

reported depend only partially from our approach, it

should be argued that the reports available online suf-

fer the same limitations and issues. This calls for a

deeper scientific exploration of the available data, to

Learning from Others’ Mistakes: An Analysis of Cyber-security Incidents

305

better evaluate the quality of the dataset and make

transparent and questionable the results.

In short, our future work will focus to make

“learning from others’ mistakes” possible for a wide

range of professionals involved in managing cyber-

security (such as technologists, insurers, or policy

makers) by providing adequate tool support to the

methodology described in this work and perform

more extensive investigations about the datasets con-

sidered here and others that will be made avail-

able to us. As a firs concrete step to promote

the use of our datasets and methodology, we pro-

vide pointers to the on-line datasets and the merged

one, plus additional material, at the following ad-

dress: https://sites.google.com/fbk.eu/ fbk-cybersec-

flagship-project.

REFERENCES

Biancotti, C. (2017). The price of cyber (in) security: evi-

dence from the italian private sector. Occasional Pa-

pers (Questioni di economia e finanza), (407).

Edwards, B., Hofmeyr, S., and Forrest, S. (2016). Hype and

heavy tails: A closer look at data breaches. Journal of

Cybersecurity, 2(1):3–14.

Klahr, R., Shah, J., Sheriffs, P., Rossington, T., Pestell,

G., Button, M., and Wang, V. (2017). Cyber security

breaches survey 2017: main report.

Ponemon Institute (2017). 2017 cost of data breach study.

https://public.dhe.ibm.com/common/ssi/ecm/se/en/

sel03130wwen/security-ibm-security-services-se-

research-report-sel03130wwen-20180122.pdf.

Romanosky, S. (2016). Examining the costs and causes of

cyber incidents. Journal of Cybersecurity, 2(2):121–

135.

statista (2018). Annual number of data breaches and ex-

posed records in the united states from 2005 to 2018.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/273550/data-

breaches-recorded-in-the-united-states-by-number-

of-breaches-and-records-exposed/.

Wheatley, S., Maillart, T., and Sornette, D. (2016). The

extreme risk of personal data breaches and the erosion

of privacy. European Physical Journal B, 89:7.

Xu, M., Schweitzer, K. M., Bateman, R. M., and Xu,

S. (2018). Modeling and predicting cyber hacking

breaches. IEEE Transactions on Information Foren-

sics and Security, 13(11):2856–2871.

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

306