The Rationale of SPV in Indian Smart City Development

Kranti Kumar Maurya and Arindam Biswas

Department of Architecture and Planning, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, Uttarakhand, India

Keywords: Smart Cities Mission, Local Government, Guidelines, Municipal Government and Urban Governance Index.

Abstract: Indian cities are largely managed by the Local Governments, empowered by the Indian Constitutional (74th

Amendment) act, 1992. In 2015, the Union Government of India introduced Smart Cities Mission (SCM), in

which 100 cities were selected to be developed as Smart City (Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, 2015a).

The Union Government introduced a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) as the implementing agency of SCM

(Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, 2015b). Each one of these 100 cities needed to establish a SPV,

which coordinate this mission. The decision to establish SPVs opens up many pertinent questions regarding

its legitimacy of being an urban institution. SPVs have not been used in overall city administration yet, so in

this area performance of SPVs, are yet to be known. The paper investigates the establishment of SPVs, its

authenticity and its contribution to city development. It checks the legal support of its constitution. The paper

argues about the achievements of the SPVs over the traditional governance process with the help of

governance analysis methods (Urban Governance Index). To streamline the paper, authors have selected (to

investigate) two Indian cities Pune and Varanasi wherever needed. The paper also discusses the historical

context of SPVs, functioning module of SPVs for project planning and implementation. Further, the findings

of the paper suggest that because SPVs are being used for a small pilot area of the cities, enlarging the SPV

mechanism to the level of Local Government may translate into the similar type of governance system.

1 INTRODUCTION

Multi-pronged problems and obstacles continuously

challenge Indian cities. Urbanisation was never at the

forefront of post-independence planned economic

policy regime. The first real effort came in 2005 when

cities were funded for seven years for urban

rejuvenation and infrastructure augmentation.

However, it is hard to decipher the colossal

difficulties amalgamated for centuries with a seven-

year programme. In between urban programmes and

policy shifts its course with the change of

governments. The earlier policies and programmes

were drastically curtailed down to introduce new

programmes. One such urban programme is to

develop 100 Smart Cities across the country. The

‘Smart Cities Mission (SCM)’ aims to drive

economic growth and improve the quality of life of

people in selected cities by enabling local

development and harnessing technology as a mean to

create smart solutions for citizens (Smart Cities

Mission Statement Guidelines, 2015). The mission

faced many challenges – urban management is the

most crucial of them. As a strategic intervention, the

government introduced a new city management tool

to manage Smart Cities, called Special Purpose

Vehicle (SPV) (Ministry of Housing and Urban

Affairs, 2015b). Establishment of SPV raises some

legitimate concern from the administration,

academia, and professionals about their constitutional

legitimacy. The goal of the paper is to study SPVs and

its relationship with the formal urban institutions. The

goal is achieved by adhering to the following

objectives:

i. To review SPV as a tool for city management;

ii. To understand SPVs networking and working

relation with the institutional governance for project

planning and implementation;

iii. To understand SPV’s role and functioning

methods in Indian SCM; and

iv. To identify its potential contribution and

constitutional legitimacy in Indian Smart Cities

development.

The questions underpinning the paper are;

i. What is the historical context of SPVs in city

management?

ii. What are the functioning module of SPV for

project planning and implementation?

Maurya, K. and Biswas, A.

The Rationale of SPV in Indian Smart City Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0007726701430150

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2019), pages 143-150

ISBN: 978-989-758-373-5

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

143

iii. How SPVs become so relevant in the Indian

SCM?

2 SPV AND ITS EVOLUTION

SPV also known as ‘variable interest entities’ or

‘Special purpose entities’ (SPE) or ‘financial vehicle

corporation’ (FVC), is a legal entity (usually a limited

company of some type or a limited partnership)

created to fulfil narrow, specific or temporary

objectives (UNECE, 2015). Companies to isolate the

firm from financial risk typically use SPVs. It may be

owned by one or many entities. SPVs started back in

the 1980s for financial management. The genesis of

SPVs occurred with ‘Junk-Bond King’ Michael

Milken and his firm Drexel Burnham Lambert (Healy

and G.Palepu, 2001).

As the name suggests, SPVs are formed for a

special purpose. Therefore, its’ powers are limited to

what might be required to attain that purpose and its

life is destined to end when the purpose is attained.

As per (Cioppa, 2005), When a corporation mentions

itself as the sponsor of a SPV, it signifies that it wants

to achieve a particular purpose, i.e. funding by

isolating an activity, asset or operation from the rest

of the sponsor's business. This isolation is important

for external investors whose interest do such hived-

off assets back, but who are not affected by the

generic business risks of the entity. In the absence of

adequate distance from the sponsor, the company is

not a SPV but only a subsidiary company. Thus SPVs

are housing devices – they house the assets

transferred by the originating entity in a legal outfit,

which is legally distanced from the originator, and yet

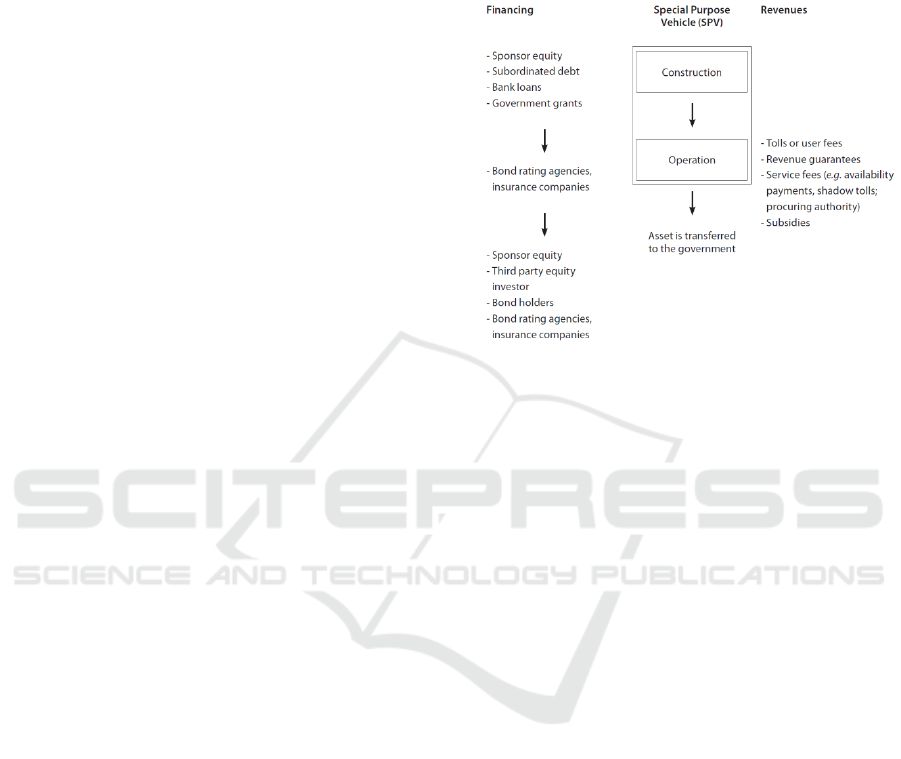

self-sustainable (Wagenvoort et al., 2010). Figure 1,

shows the creation of a SPV to ensure the functioning

of projects. Prime usages of SPVs till date are

securitisation, risk sharing, financial engineering,

asset transfer, to maintain the secrecy of intellectual

property, financial engineering, regulatory reasons,

property investing etc (Crawford, 2003). SPVs are

also used for sales and purchase contracting,

insurance, raising capital (UNECE, 2015).

Members of a SPV are mostly sponsoring entities

like companies and individuals. A SPV can also be a

partnership firm. Individuals or institutions from

abroad can also sponsor it. A SPV enterprise is

formally registered with a national authority and is

subject to fiscal and legal obligations of the economy.

In terms of organizational form, it makes sense to

have a SPV, own and manage the infrastructure asset

until the investment cost has been recouped (Eldrup

and Schutze, 2013). According to (Bratton and

Levitin, 2013), the SPVs never fully coalesce as

independent organizations that take actions in pursuit

of business goals. They are companies running on

autopilot that serve one purpose - removing assets and

liabilities from the parent company’s balance sheet.

Figure 1: SPV’s financial lifecycle. (Wagenvoort et al.,

2010).

The success of a SPV in dealing with these

conflicts depends on two factors – Firstly, the quality

of the legal institutions and laws. Secondly, the

particulars of each relationship and contract affecting

risk perceptions of debt holders. SPV for project

planning and implementation, focus more on project

finance and delivery. Companies have a wider

purpose and may do several things as per the

memorandum of association. However, SPVs are

established for the limited and focused scope of

operation. This is primarily to provide comfort to

lenders who are concerned about their investment.

The alternative to managing the risks of SPVs is

an ethical standard and strict legal support to not to

use them inappropriately. The benefits and the uses of

the SPVs do not justify the risks involved in them to

be misused. Next section throws light on why and

how the SPVs become a tool for project

implementation for India’s SCM.

3 SPV IN INDIA’S SMART CITIES

MISSION FOR PROJECT

IMPLEMENTATION

Gujarat International Finance Tec (GIFT) City is one

of the first Smart City initiatives in India. GIFT City

proposed to have separate SPVs into specific viable

components for its development. SPVs have been set

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

144

up to implement the critical utility components

through major private sector participation such as

district cooling systems limited, water infrastructure

limited, waste management services limited, SEZ

limited, power company limited, ICT services

limited. GIFT City development may have initiated

the idea of SPV mode implementation of SCM.

(Gujarat International Finance Tec-City - Global

Financial Hub)

The erstwhile Planning Commission of India in its

Twelfth Plan (2012 – 2017) envisioned to create

Smart Cities to address India’s urbanisation

challenges (Bholey, 2016). As the government’s

flagship mission moved from conceptualisation

towards the implementation phase, questions have

arisen regarding the mission (Shahana Chattaraj).

Debates over implementation gained momentum

amidst calls for closer review of the factors involved

and the need to incorporate learning from previous

such programs (Ravi and Bhatia, 2016). A key

uncertainty that had emerged was the constrained

organizational capability of Indian Urban Local

Bodies to meet the challenges posed by this new type

of development (Praharaj, Han and Hawken, 2018).

Ironically, these questions were fuelled by the

Government of India’s own urban policy assessment

that pointed out political economy factors and

inadequate management capacity as the key

challenges affecting urban reform in India (Strategic

Plan of MoUD for 2011-16). Various well-regarded

global enterprises such as the World Economic

Forum (2016) and the Brookings Institution (Carol L.

Stimmel, 2016) in their assessment on Smart Cities

development in India highlighted that the concept of

a planned urban administration was yet to be

addressed in Indian cities and the current nature of

government silos would pose a major challenge in the

implementation of mega future developments.

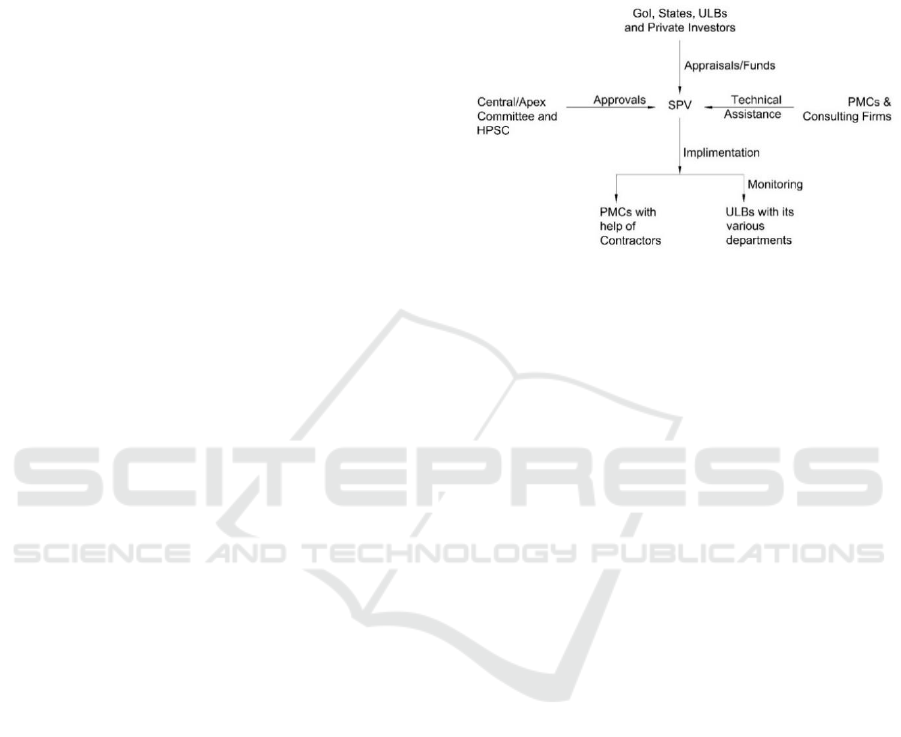

The Central Government established the Apex

Committee and High-Powered Steering Committee

(HPSC) that approved SPV’s establishment (Figure

2). These are companies formed by a partnership

between the State and Urban Local Bodies to expedite

the process of development. However, it is yet to be

examined about the process of formation of SPVs and

its impact on empowering the Urban Local Bodies.

Coordination between the conventional forms of

Local Governments and parastatals (infrastructure

delivery agencies) is also a matter of deep

introspection. A SPV function as a nodal

implementing agency for SCM projects.

The SPV is headed by a chief executive officer

(CEO), supported by a board of directors with

representation from the Central Government, the

State Government and the local public utility

providing agencies. The overall idea of establishing

SPVs rather involving Municipal Corporations for

project planning and implementation is to exhibit a

high-performance urban system and bring agility in

strategic decision-making.

Figure 2: SPV’s Establishment for Functioning of SCM.

The Local Governments require approval from the

State Government for various activities, which can be

unilaterally performed by a SPV. It is also noted that

the SPVs can engage with citizens through ICTs

efficiently than the Local Governments. SPVs may

also bypass regular institutional hurdles in

implementing some of its plans. SPVs enjoy relative

freedom to implement and manage the SCM. The

SPVs are authorized to appoint Project Management

Consultants (PMC) for planning, design, develop,

manage and implement area-based projects. SPVs

may take assistance from any of the empanelled

consulting firms and the handholding agencies

approved by the Ministry of Housing and Urban

Affairs, (MoHUA). SPVs need to follow a transparent

and fair process for procurement of goods and

services as prescribed in the concerned State/Local

Government’s financial rules. SPVs may also refer to

the model framework developed by the MoHUA. The

government hopes that Smart City projects will attract

private participation as PPP mode.

The SCM encourages the State Governments and

the Local Governments to delegate the following to

the SPVs as per the SCM guidelines (2015):

-The rights and obligations of the Municipal Council

with respect to the SCM to the SPV;

-The decision-making powers available to the ULBs;

-The approval or decision-making powers available

to the UDD/ULB;

-The matters that require the approval of the State

Government.

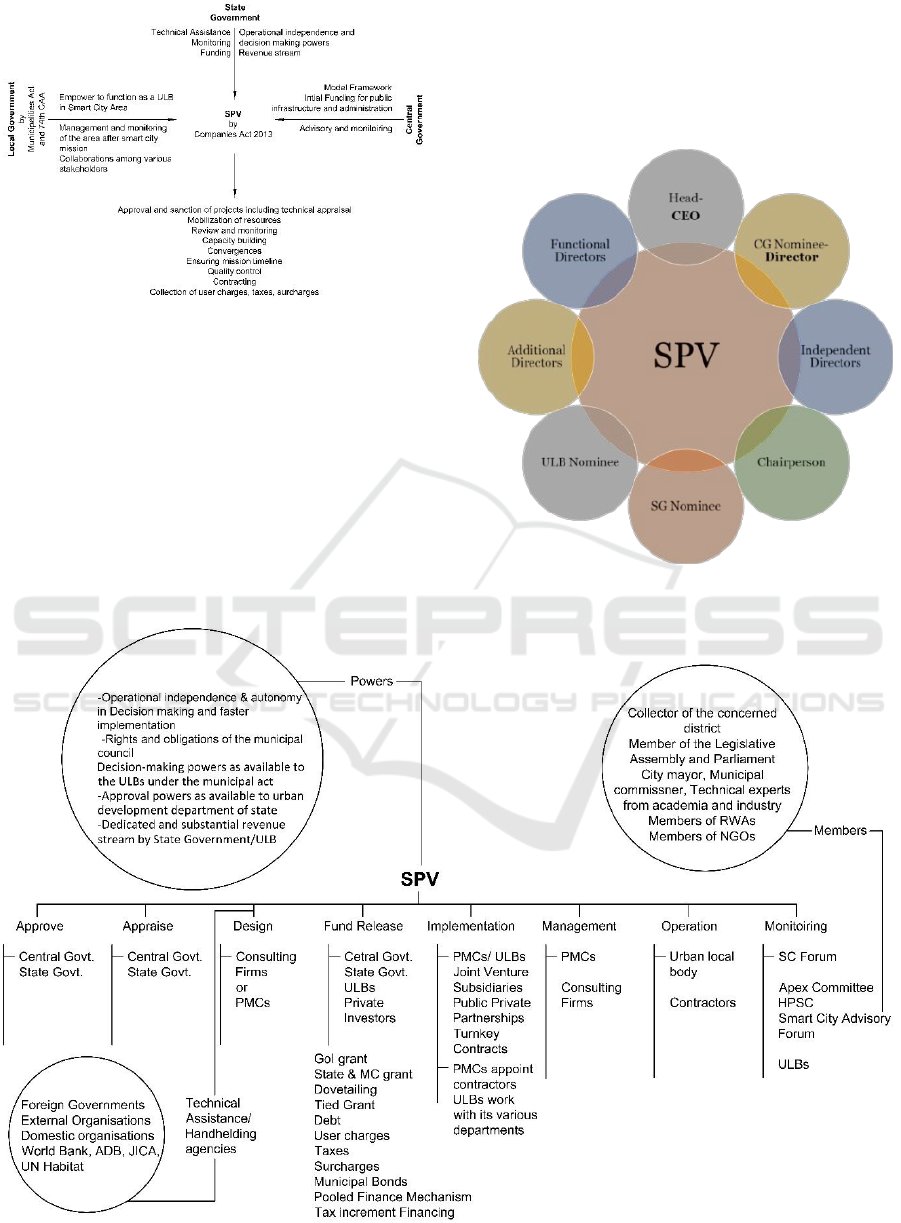

The contributions and responsibilities of different

tiers of Government are presented in figure 3.

The Rationale of SPV in Indian Smart City Development

145

Figure 3: Relationship of SPV with 3-Tiers of Government.

Primary responsibilities of SPVs are to plan,

appraise, approve, release funds, and implement,

manage, operate, monitor, and evaluate projects (figure

5). Implementation of projects may be done through

joint ventures, subsidiaries, public-private partnership

(PPP), turnkey contracts, etc. The project cost may be

suitably dovetailed with continuous revenue streams.

SPVs are working with the Local Governments. In

many cases, the Municipal Commissioner of the Local

Government is appointed as the CEO of the SPV.

Some SPVs also appointed Municipal Corporations as

the implementing agency for the projects. Many are

hiring PMCs to implement SCM projects. The SPVs

have a multi-tier structure on its Board, taking

members from each hierarchy of the governance

system of India (figure 4).

Figure 4: The composition of the SPV board.

Figure 5: Powers and Responsibilities of SPV in Smart City Mission.

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

146

Apart from setting up SPVs, aspiring Indian Smart

Cities are forming Smart City Advisory Forum at the

city level aiming to drive collaboration among

various stakeholders and monitoring organisations.

The key role of the advisory forum is to review the

suggestions provided by citizens, prioritize projects

and do a periodic review of the project outcomes.

This nature of consultative structure was never seen

in existence in India’s urban landscape and is

believed to be the beginning of collaborative

governance in Indian cities. Authors have gone

through the cases Varanasi and Bhubaneswar Smart

City to further study from the actual scenarios of the

SPVs.

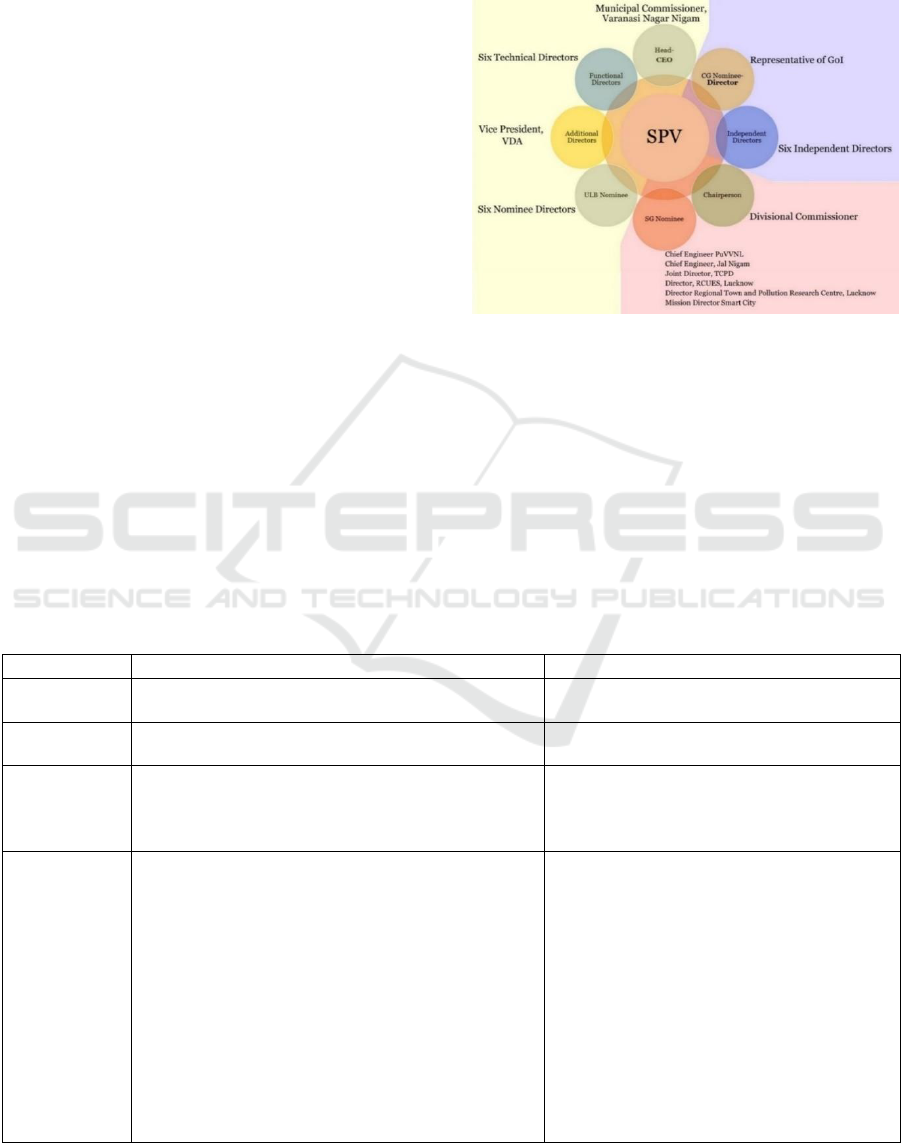

In Varanasi Smart City SPV board, the Nominee

Director and the Independent Directors represent the

Government of India. The State Government is

represented by the Chairperson of the SPV

(Divisional Commissioner of the Varanasi Division)

and nominees from departments such as PuVVNL,

Jal Nigam, TCPO, RCUES, RTPRC, and Mission

Director of the State. City level representation

includes the Nominee Directors, Technical Directors,

Additional Director (VDA-Vice President) and the

CEO (Municipal Commissioner) of SPV (Figure 6).

Bhubaneswar Smart City is one of the early

establishers of a functioning SPV. The city of

Bhubaneswar has conceived SPV as a master

developer, similar to the context of private townships.

It explores arrangements with builders, technology

vendors and financiers. The organisational structure

of Bhubaneswar Smart City SPV is very different

from the existing SCM guidelines. It is more like an

enterprise structure rather than a bureaucratic board

committee.

Figure 6: Varanasi Smart City SPV Administration.

SPVs and Formal Governance (ULBs) in India

SPV is the project-implementing agency for Smart

Cities Mission, and Urban Local Body (ULB) is the

traditional agency for city development and

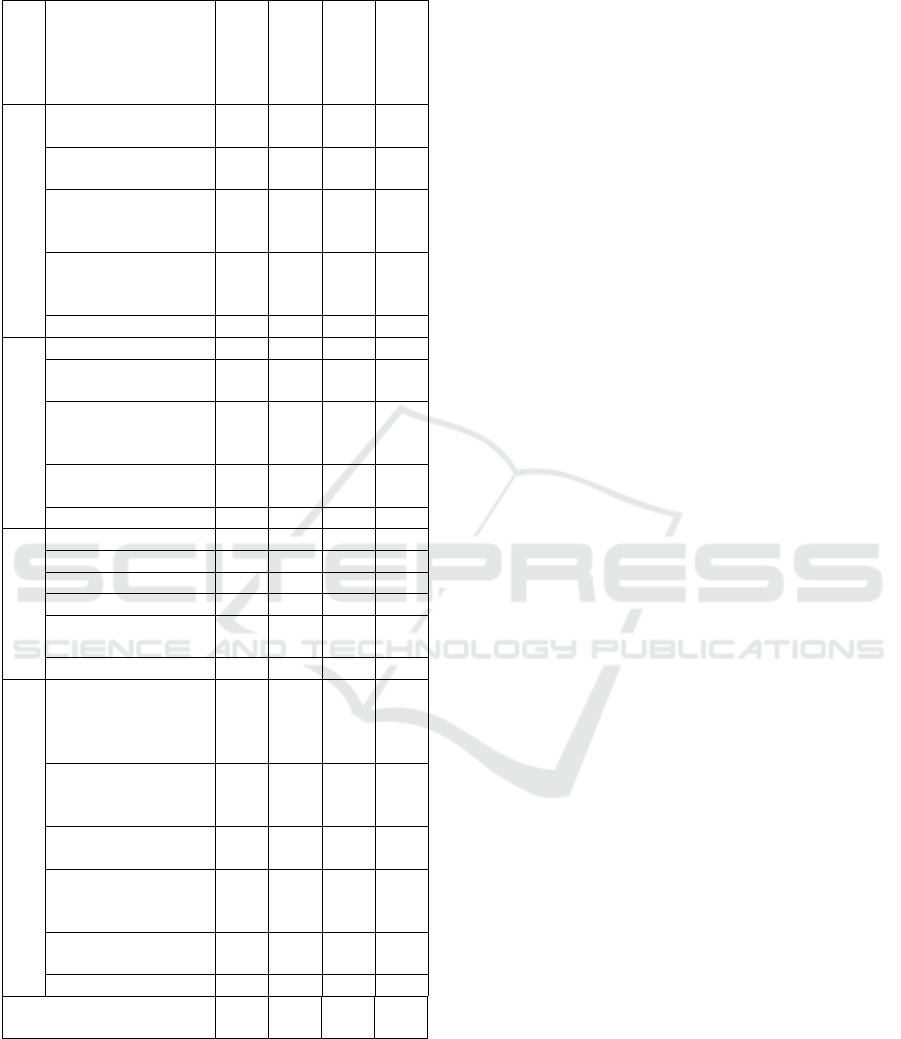

management. The comparison (table 1) takes the

example of Pune city for both types ULB and SPV.

The comparison suggests that as SPVs develop a

very small area for Smart Cities, most of the city area

is left to be managed by the ULB. Therefore, states

need to push for implementation of urbanization

Table 1: Comparison of ULB and SPV governance.

Attributes

ULB

SPV

Operation

Area

Municipal Area

A small area for Area-based developments; a

municipal area for Pan City Developments.

Democratic

Inclusion

Democratic inclusion in decision making in form of

councilors.

Mandatory only in form of the advisory

forum; councilors at Smart City board.

Sources for

Capital

Capital for ULB comes from own revenues, Finance

Commission, Central Govt. schemes, municipal

bonds, Central Govt. grants, Loans and PPPs.

SPV have capital from SCM, Central Govt.

Schemes, and Loans (Municipal bonds,

Project level infra bonds, ADB, WB, JICA);

Share Capital, User charges, taxes.

Organizational

structure,

departments,

committees,

etc.

ULBs have various departments such as

administration, engineering, health, ward offices,

social welfare, revenue, emergency services, nature

and environment, information technology.

For example, Pune Municipal Corporation has

two wings, one is administrative wing headed by the

Municipal Commissioner and another is elected wing

headed by the mayor.

There are two major bodies at the municipal level

in Pune- General body and Standing Committee. The

general body takes policy decisions for ULB, which

includes all the councilors and commissioner.

Standing Committee takes financial decisions for the

ULB.

Board of directors take decisions, which is a

smaller body including a mix of people from

the three tiers of government and various

parastatals, which helps in taking quick

decisions.

-Audit Committee; Finance Committee;

Nomination & Remuneration Committee;

Risk Management Committee; Compensation

Committee; Share transfer & Allotment

Committee; Project Management Committee;

Directors; Key Managerial Posts- Chairman,

CEO, CFO, Company Secretary;

The Rationale of SPV in Indian Smart City Development

147

Table 1: Comparison of ULB and SPV governance. (Cont.).

Vision

To provide and maintain civic services (supply of

water, electricity, road maintenance, sewerage

disposal, sanitation, parking, taxes and fees

collection). Urban planning including town planning,

Regulation of land use and construction of buildings,

Planning for economic and social development.

The vision of the SPV is to provide Smart

City components in the Smart City area.

SCM objectives are to provide water

supply, electricity, education and health

services, safety and security, housing,

environmental sustainability, urban transport.

Functions

Constitution of special committees or joint

committees. Joining with a cantonment authority or

any local authority. Sanctioning of the acceptance, or

acquisition of immovable property; Sanctioning the

taking of any property on lease for a term exceeding

three years.

Adoption of the budget; Determination of rates of

taxes; To vary or alter the budget estimates; Tax

imposition; To abolish or alter a tax; Taxes

consolidation; To abandon or sanction the scheme

with or without modifications submitted to it by the

Development Committee; To determine whether the

establishment of new private markets shall be

permitted in the City or in any specified portion of the

City.

The company plan, implement, manage and

operate the Smart City development projects.

The key functions and responsibilities of the

Company include:

Approval and sanctioning of projects,

technical appraisal, execution, mobilization of

resources, third-party review and monitoring,

capacity building, timely completion, review

of activities of the mission including budget,

implementation of projects, and coordination

with other missions/schemes, Incorporation of

joint ventures and subsidiaries and enter into

public-private partnerships including with

foreign entities as may be required for the

implementation of the Smart Cities Mission.

Determine and collect user charges.

reforms from 74

th

CAA, Local Governments are still in

need of proper empowerment. The Smart Cities

Mission Statement & Guidelines and The Companies

Act mandate SPVs. Whereas Urban Local Bodies are

directed by many laws and acts. The major difference

is the organisational structure, capital sources and

functioning method.

4 EVALUATION OF ULBS AND

SPVS WITH THE HELP OF

URBAN GOVERNANCE INDEX

(UGI)

Authors took two cities for the purpose of comparison

Pune and Varanasi. City selection is based on data

availability and relevance to the topic. Both of these

cities are listed in SCM and have Municipal

Corporations as ULB. Data for Municipal

Corporations are mostly available on their websites

and reports. However, Authors also visited the cities to

verify the available data and get unavailable data.

Authors did structured interviews of the city officials

in both the cities. Pune Smart City has established a

SPV, Pune Smart City Development Corporation

Limited (PSCDCL) for the governance. Varanasi

Smart City has also established a SPV, Varanasi Smart

City Limited for governance. PSCDCL is the only

Smart City SPV that has published annual reports and

various other data regarding the works of the same. So,

for the SPV governance, authors have data of PSCDCL

and for ULBs, authors have data of Pune Municipal

Corporation (PMC) and Varanasi Municipal

Corporation (VMC).

Urban Governance Index is an index developed by

the United Nations for the measurement of governance

as per governance principles. It has 4 indicators and 18

parameters (UN-HABITAT, 2004). A detailed

background data collection and empirical calculations

have been done. A summarized result of the evaluation

is in table 2.

The scores show that Municipal Corporations are

working better than the newly established SPVs. The

data for SPVs have not been available in exact formats,

which can account for a little loss in scores but not to

the high impact. SPVs establishments are new so data

have been available for only 1-2 years. For the more

reliable and accurate empirical databased study, we

need to wait for some years, but as per status, SPVs are

behind the ULBs in performance.

For the purpose of UGI, authors modified and

interpreted the relevant and comparable SPV data in

place of ULBs. For example, SPVs have Director,

CEO, CFO and Company secretary as the key

positions in place of or equivalent of Mayor, Deputy

Mayor etc. There is no councillors and no elections in

place so, no voter turnout. This is not a Municipal

Corporation so, no mayor. All the members on board

are selected from the various organisations. SPVs are

to implement a mission; therefore, there is no citizen

charter or published performance delivery standards,

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

148

Table 2: Urban Governance Index, Indicators and

Parameters, Summarized Scores.

Indicators

Parameters

Max.

PMC

VMC

PSCDCL

Effectiveness

Local government

revenue per capita

0.35

0.32

0.22

0.28

Local government

transfers

0.20

0.20

0.10

0.15

The ratio of

mandatory to actual

tax collection

0.20

0.20

0.18

0.00

Published

performance

standards

0.25

0.00

0.00

0.25

Total

1.00

0.72

0.50

0.68

Equity

Citizen charter

0.20

0.00

0.00

0.30

The proportion of

women councillors

0.25

0.25

0.17

0.10

The proportion of

women in key

positions

0.20

0.10

0.20

0.10

Pro-poor pricing

policy

0.35

0.15

0.15

0.15

Total

1.00

0.50

0.52

0.65

Participation

Elected Council

0.15

0.15

0.15

0.00

Election of Mayor

0.15

0.08

0.08

0.00

Voter turnout

0.25

0.14

0.13

0.00

People’s forum

0.20

0.20

0.20

0.20

Civic Association

(per 10000)

0.25

0.00

0.00

0.00

Total

1.00

0.57

0.56

0.20

Accountability

Formal publication

of contracts,

tenders, budget and

accounts

0.20

0.20

0.20

0.20

Control by higher

levels of

government

0.20

0.10

0.10

0.10

Anti-corruption

commission

0.20

0.00

0.00

0.00

Disclosure of

personal income

and assets

0.20

0.20

0.20

0.00

Regular

independent audit

0.20

0.20

0.20

0.20

Total

1.00

0.70

0.70

0.50

Final Scores (Average of

Indicators scores)

1.00

0.62

0.57

0.48

SPVs rather have annual reports. There are no elected

officials as of SPVs, so disclosure of income and assets

become void. As per the guidelines, SPVs should collect

taxes in its area, but none of the SPVs collects taxes yet.

The delegation of tax collection powers from Local

Government to SPV has not happened yet.

5 CONCLUSION

SPVs for the implementation of SCM can be seen as

a development of a collaborative system to engage

urban stakeholders and citizen in the decision-making

process (Praharaj, Han and Hawken, 2018). In an

attempt to strengthen this system, it can be observed

that this system is sidestepping the democratic

process of local self-government by replacing them

with a more capitalistic business-oriented entity

(Exiner, 2012). Since 1992, the government has been

trying to implement the 74th CAA for uplifting the

capacity of the Municipal Corporations;

establishment of SPVs is showing the loss of

confidence in Municipal Corporations and

demeaning the efforts of two decades.

Many of the SPVs are working with a similar

workforce as of the Municipal Corporations.

Therefore, how the SPVs will manage to deliver the

expected urban transformation is yet to be seen.

Setting up a SPV can also be seen as an attraction

point for the private shareholding, but until now, none

of the SPVs has private shareholding, which tells that

SPVs have been failed to attract the trust of the

external investors; though, external organizations

have been part of the SCM in form of project

consultants and project implementers.

With SPVs in place, the State government has a

say in local affairs, which may interfere with Local

Governments’ independence. SPVs have a very small

part of the city; beyond this area, Municipal

Corporation has to function as earlier. Some of the

selected cities in SCM already have a better

mechanism to work towards Smart Cities in form of

ULBs. The inclusion of these cities in the SCM is

creating conflicts in their process of working. The

accountability of SPVs is questionable because there

is no mandatory public and democratic

representation. Without any clear accountability to

the citizen, SPVs may function irrationally for

revenue generation. SPVs are established for

objective development and efficient decision-

making, which is also a subject of local politics.

Therefore, bypassing democratic inclusion may not

contribute to success. Convergence is also one of the

SCM ambitions, but there are no clear guidelines for

it. How two schemes under a city, working in

different areas converge, is yet to be seen.

Indian cities are dysfunctional which largely

implies the lack of infrastructure. To develop

infrastructure investment is required, which cities

were not able to get on their own, earlier. By

establishing the SPVs, these cities can attract

investment; because, it is an independent body from

The Rationale of SPV in Indian Smart City Development

149

Municipal Corporations, working on a much smaller

area to achieve first world specifications. SPVs have

stable leadership, which makes it stronger in terms of

governance. The size of the area for SCM is another

positive for the success of SPVs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

NBCC (India) Limited, formerly known as National

Buildings Construction Corporation Ltd., funded the

research under the project ‘Framework to manage

construction and governance of smart cites building

in India’.

REFERENCES

Bholey, M. (2016) ‘India’s Urban Challenges and Smart

Cities: A Contemporary Study’, Scholedge

International Journal of Business Policy & Governance

ISSN 2394-3351, 3(3), pp. 17–38. doi:

10.19085/journal.sijbpg030301.

Bratton, W. W. and Levitin, A. J. (2013) ‘A Transactional

Genealogy of Scandal: From Micheal Milken to Enron

to Goldman Sachs’, Southern California Law Review,

86, pp. 783–869.

Carol L. Stimmel (2016) Building Smart Cities in India.

Cioppa, P. (2005) ‘The efficient capital market hypothesis

revisited: Implications of the economic model for the

united states regulator’, Global Jurist Advances, 5(1).

City, G. (2016) Gujarat International Finance Tec-City -

Global Financial Hub. Available at: http://www

.giftgujarat.in/ (Accessed: 28 August 2018).

Crawford, P. J. (2003) ‘Special Purpose Entities’,

Finance/Investing/Accounting. Graziadio Business

Review, 6(2), pp. 1–4.

Eldrup, A. and Schutze, P. (2013) Organization and

Financing of Public -Infrastructure Projects.

Exiner, R. (2012) Good Governance Guide. Available at:

http://www.goodgovernance.org.au/.

Healy, P. M. and G.Palepu, K. (2001) ‘The fall of Enron’,

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(Dec 17), pp. 30–

36. doi: 10.1257/089533003765888403.

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (2015a) Prime

Minister launches Smart Cities, AMRUT, Urban

Housing Missions, PIB. Available at: http://pib.

nic.in/newsite/archiveReleases.aspx (Accessed: 12

February 2019).

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (2015b) Special

Purpose Vehicles (SPV) to implement Smart Cities

Project, PIB. Available at: http://pib.nic.in/newsite

/archiveReleases.aspx (Accessed: 12 February 2019).

MoUD (2011) Strategic Plan of MoUD for 2011-16.

Praharaj, S., Han, J. H. and Hawken, S. (2018) ‘Towards

the Right Model of Smart City Governance in India’,

International Journal of Sustainable Development and

Planning, 13(2), pp. 171–186. doi: 10.2495/SDP-V13-

N2-171-186.

Ravi, S. and Bhatia, A. (2016) For Smart Cities to Succeed,

Strengthening Local Governance Is a Must, The Wire.

Available at: https://thewire.in/politics/smart-cities-to-

succeed-need-to-strengthen-local-governance

(Accessed: 13 February 2019).

Reforms to accelerate the development of India’s smart

cities shaping the future of urban development &

services (2016). Available at: http://www3.weforum

.org/docs/WEF_Reforms_Accelerate_Development_In

dias_Smart_Cities.pdf.

Shahana Chattaraj (2017) Are ‘Smart Cities’ enough for

India?, IGC. Available at: https://www.theigc.org/

blog/are-smart-cities-enough-for-india/ (Accessed: 13

February 2019).

Smart Cities Mission Statement Guidelines (2015).

Available at: http://smartcities.gov.in/upload/upload

files/files/SmartCityGuidelines(1).pdf (Accessed: 6

June 2017).

UN-HABITAT (2004) ‘Urban Governance Index’,

Conceptual Foundation and Field Test Report,

(August), pp. 1–65. Available at: papers3://publication

/uuid/4B833808-137D-4037-A51F-BBE1F82E9C7F.

UNECE (2015) ‘Chapter 4 - Special Purpose Entities’, in,

pp. 39–65.

Wagenvoort, R. et al. (2010) Public and private financing

of infrastructure: Evolution and economics of private

infrastructure finance. 1st edn. Edited by H. Strauss.

European Investment Bank: Economic and Financial

Studies.

SMARTGREENS 2019 - 8th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

150