A Food Value Chain Integrated Business Process and Domain Models for

Product Traceability and Quality Monitoring: Pattern Models for Food

Traceability Platforms

Estrela Ferreira Cruz

1,2

and Ant

´

onio Miguel Rosado da Cruz

1,2

1

ARC4DigiT - Applied Research Centre for Digital Transformation, Instituto Polit

´

ecnico de Viana do Castelo, Portugal

2

Centro ALGORITMI, Escola de Engenharia, Universidade do Minho, Guimar

˜

aes, Portugal

Keywords:

Business Process Modeling, BPMN Process Model, Domain Model, Value Chain Integration, Perishable

Products, Food Products, Quality Monitoring and Tracing, Product Lot Localization Traceability.

Abstract:

Traceability of product lots in perishable products’ value chains, such as food products, is driven by increasing

quality demands and customers’ awareness. Products’ traceability is related to the geographical origin and

location of products and their transport and storage conditions. These properties must be continuosly measured

and monitored, enabling products’ lots traceability concerning location and quality throughout the value chain.

This paper proposes pattern integrated business-process and domain models for food product lots traceability

in the inter-organizational space inside a food value chain, allowing organizations to exchange information

about the quality and location of product lots, from their production and first sale until the sale to the final

customer, passing through the transportation, storage, transformation and sale of each lot. The paper also

presents the process followed for obtaining these two pattern models. Three exploratory case studies are used,

towards the end of the paper, for validating the proposed business-process and domain pattern models.

1 INTRODUCTION

Consumers have a growing interest in knowing ev-

erything about the products they consume, and have

more trust in brands that have a tight control of their

products’ quality. They also want to know the origin

of the products they are buying or eating, and where,

how and in what conditions products are transported

and stored. In what concerns fresh products, however,

it may not be easy to know the quality or origin of

what they are buying. Collecting quality control and

traceability data from all steps of a fresh foods value

chain, from product’s harvesting (capture, creation) is

a complex task involving many business partners.

Organizations in a particular value chain exchange

products, documents, and information that allow them

to add value to the products they buy before trans-

forming and/or selling them to the next link in the

value chain. Internationalization and digital transfor-

mation demand from a value chain’s operators an in-

creasing interconnectivity and integration. Addition-

ally, in perishable products’ value chains, such as food

(e.g. fishery, meat, milk and dairy, fruits) or phar-

maceutical products, increasing quality demands and

customers’ awareness entails knowing the geograph-

ical origin of products and that products location and

their transport and storage conditions are continuosly

measured and monitored. While the geographical ori-

gin is most important for fresh or transformed agri-

cultural, dairy products, etc., especially when talking

about products with protected designation of origin,

transport and storage conditions are important both

for perishable food products, and for other products

that bear a validity date, including pharmaceutical

products. Products’ lots localization is also very im-

portant, especially when public health may be at stake

(remember the cases of mad cow disease or african

swine fever) and products’ lots must be recalled.

The increasing interconnectivity of a value chain’s

operating organizations demands better integration of

their processes, either by allowing business partners

to interact with the systems that support the processes

through an external business partners user interface

(Cruz and da Cruz, 2018), or by directly integrating

the companies processes and systems that create prod-

uct information and enable the exchange of informa-

tion. The supply-chain oriented business-to-business

(B2B) systems’ integration, aiming the interchange of

information and documents about trading, payments,

etc. is thoroughly covered by the state of the art.

Cruz, E. and Miguel Rosado Cruz, A.

A Food Value Chain Integrated Business Process and Domain Models for Product Traceability and Quality Monitoring: Pattern Models for Food Traceability Platforms.

DOI: 10.5220/0007730502850294

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterpr ise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), pages 285-294

ISBN: 978-989-758-372-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

285

These B2B oriented integration solutions are not suit-

able for traceability and quality monitoring purposes,

though, because of the following reasons:

• Information about products localisation is not typ-

ically maintained in any of the value chain’s oper-

ators systems. This makes impossible for compa-

nies to be sure about the origin of a product, and

impedes the knowledge of the locations to where

a lot has been splited and distributed, when lot re-

trieval from market (lot recall) is needed.

• Products quality information is registered in each

value chain operator (typically handwritten on a

notebook), but is never shared among business

partners. This makes impossible for a company to

be sure that the products it received under appar-

ently acceptable environmental conditions, have

not been subjected to product spoiling or deterio-

ration conditions at any point in the value chain.

Food traceability is of utmost importance, namelly

as it allows to avoid forgeries, by assuring the origin

of a product, especially when talking about products

with protected designation of origin; and, it enables

to recall products’ lots, because of food contamina-

tion or other threats to the public health. Food trace-

ability requires a common value chain’s platform that

enables sharing information about products and their

agreed quality parameters along the value chain.

In these cases, traceability information will en-

able identifying the origin of each product lot and all

the geographical location points where it has passed,

along with information about the packaging, transport

and storing conditions (e.g. temperature, humidity),

and about the observed quality of the product at each

point. This grants greater security to consumers.

The main contribution of this paper is the presen-

tation of a pattern business process model for perish-

able products value chains, and the corresponding do-

main entities model. These models fill the gap space

that lies between operators in a value chain.

The structure of presentation is as follows: In the

next section, related work is presented. In section 3,

a value chain’s integrated business process model is

presented as a pattern for perishable products value

chains. Section 4 presents the corresponding pattern

domain model. Section 5 arguments towards valida-

tion of the results obtained and section 6 concludes

the paper and discusses directions for future work.

2 RELATED WORK

In 2002, the European Union created a directive re-

garding the traceability in food sector, assuring in-

formation flow transparency and traceability (Regu-

lation (EC) No 178/2002). This directive defines a set

of principles, requirements and procedures in matters

of food and feed safety, covering all stages of food

and feed production and distribution (UNION, 2002).

Since then several authors proposed frameworks to

support the traceability in feed and food value chains.

ISO 22000 series on food management systems

also addresses the safety of food products. ISO

22005:2007 Traceability in the feed and food chain

General principles and basic requirements for system

design and implementation, is the most recent series

of food safety standards. ISO 22005:2007 gives the

principles and specifies the basic requirements for the

design and implementation of a feed and food trace-

ability system (22005:2007, 2007).

In (Regattieri et al., 2007) the authors propose

a platform to support the traceability of the famous

Italian cheese Parmigiano Reggiano from the bovine

farm to the final consumer. The framework supports

the identification of the characteristics of the product

in its different aspects along the value chain: bovine

farm, dairy, seasoning warehouse and packaging fac-

tory. The system developed is based on a central

database that collects data in all identified steps in the

food chain. Some of the information is automatically

collected by using sensors, bar codes, etc. Other in-

formation is collected manually.

In (Ioannis Manikas, 2009) the authors present the

first step in a project to design and create a Web plat-

form to support food traceability for dairy products.

The first phase of the project includes the design of a

reference model for a generic dairy supply chain. The

authors identified three main phases in a supply chain,

namely natural environment, transformation and dis-

tribution. The authors also identify the main entities

involved (actor, container, material and sample) and

present a class diagram for each entity.

Folinas et al. propose a web application for mod-

eling agricultural processes and data. The proposed

application highlights the collaborative effort in mod-

eling and integration of logistics processes assuring

that all business partners have access and share infor-

mation (Folinas et al., 2003). For that, they define

standards and specify the exchanged information.

Dabbene and Gay present new methods for mea-

suring and optimizing the performance and cost of

traceability systems by using graphs. A food produc-

tion process is seen as a sequence of storage/carrying

actions and of unit operations. A unit operation repre-

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

286

sents a product at a time. Each container/processing-

unit that individually stores/processes a product, at

a certain time, is modeled as a node in a graph

(Dabbene and Gay, 2011).

Palma-Mendoza and Neailey proposed an ap-

proach to integrate the business processes of the en-

tities involved in a supply chain. The main aim is

to guide the business process redesign to support e-

business, thus focusing supply chain B2B integration

and not a value chain oriented organizational collabo-

ration (Palma-Mendoza and Neailey, 2015).

Bevilacqua et al. propose a business process

reengineering for a supply chain of vegetable prod-

ucts (fresh vegetables, canned vegetables, mixed veg-

etables, cooked and pre-cooked vegetables) (Bevilac-

qua et al., 2009). They also suggest software system

design models for managing product traceability. The

authors present a framework based on EPCs (event-

driven process chains) and use ARIS tool to create a

Web interface to provide information to the final con-

sumer (Bevilacqua et al., 2009).

Meroni et al. propose an approach to integrate

and coordinate multi-party business processes and

present a prototype to demonstrate the proposed ap-

proach (Meroni et al., 2018). The paper presents a

methodology to translate BPMN processes to E-GSM

(Extended-Guard-Stage-Milestone) notation.

All the mentioned approaches propose specific so-

lutions for specific problems, and only a few present

specific business process or domain models. Here, a

pattern solution is proposed for any food value chain

traceability problem, namely a pattern business pro-

cess model and the associated pattern domain model.

3 MODELING THE INTEGRATED

BUSINESS PROCESS

This section presents the creation of the integrated

business process model for traceability and quality

monitoring of food products.

After having visited several producers, small

farmers’ associations, food processing industries, dis-

tributors, and supermarkets, and having participated

in the identification and design of several food chain

operators’ product traceability processes, of which

two are presented here, the similarity of different food

value chains, in terms of activities needed to address

traceability and quality monitoring, became apparent.

The approach consisted in eliciting and analyzing

a set of productive business process models from dif-

ferent food value chains’ operators (milk and dairy,

fruit, fisheries, vegetables), understand their occur-

ring order in the chain and integrate them, to obtain

a pattern business process model for traceability and

quality monitoring in food value chains.

To model business processes we are using BPMN

(Business Process Model and Notation), which is the

main standard process modeling language and one of

the most used for that purpose (Cruz et al., 2014).

Created by OMG for providing a notation clear to all

stakeholders involved in Business Process Manage-

ment (BPM), BPMN is easy to understand and usable

by people with different roles and training from top

managers to IT professionals (OMG, 2011), and is ac-

tually used both in academia and in organizations.

Business Process (BP) model diagrams define a

set of business activities carried out by an organiza-

tion for the attainment of a goal (product or service).

This type of model describes a BP internal to a spe-

cific organization(OMG, 2011). Yet, in this paper, we

do not use BPMN in the “usual” form. In fact, the

BPMN business process model is being used as a sim-

ple and easy way to understand and identify all the

activities that affect a product lot (or batch). So, in

this paper, the main lane (in the main pool) does not

represent nor a company neither a business partner.

Instead, it represents a product lot. So, business pro-

cesses are used here to focus our attention in the ac-

tivities that involve, or affect, a products lot and about

which a traceability platform needs to receive and

store information. External participants, in the mod-

els, represent the value chain operators responsible for

providing information about the activity with which

they are exchanging messages. These messages rep-

resent the information that a participant needs to pro-

vide. The activities are, in fact, executed by the par-

ticipants, represented as external participants sending

messages to the corresponding value chain activity.

The traceability platform’s main goal is to gather

and store all the relevant information from value chain

activities, to be able to identify: what was done; who

did it; when it was done; where it was done; under

what conditions it was executed. Thus, all operators

involved in the value chain must be identified.

For this presentation, and due to space limitations,

we have selected two different flows of activities in

food value chains. The next subsections present two

value chain business process models, respectivelly

about fresh vegetables, in subsection 3.1, and freeze-

dried apples, in subsection 3.2. Finally, subsection 3.3

presents a process model integrating all food value

chain’s activities, not just from the two cases pre-

sented, but also from case studies from other food

value chains (e.g. fishery, meat, aquaculture, dairy).

A Food Value Chain Integrated Business Process and Domain Models for Product Traceability and Quality Monitoring: Pattern Models for

Food Traceability Platforms

287

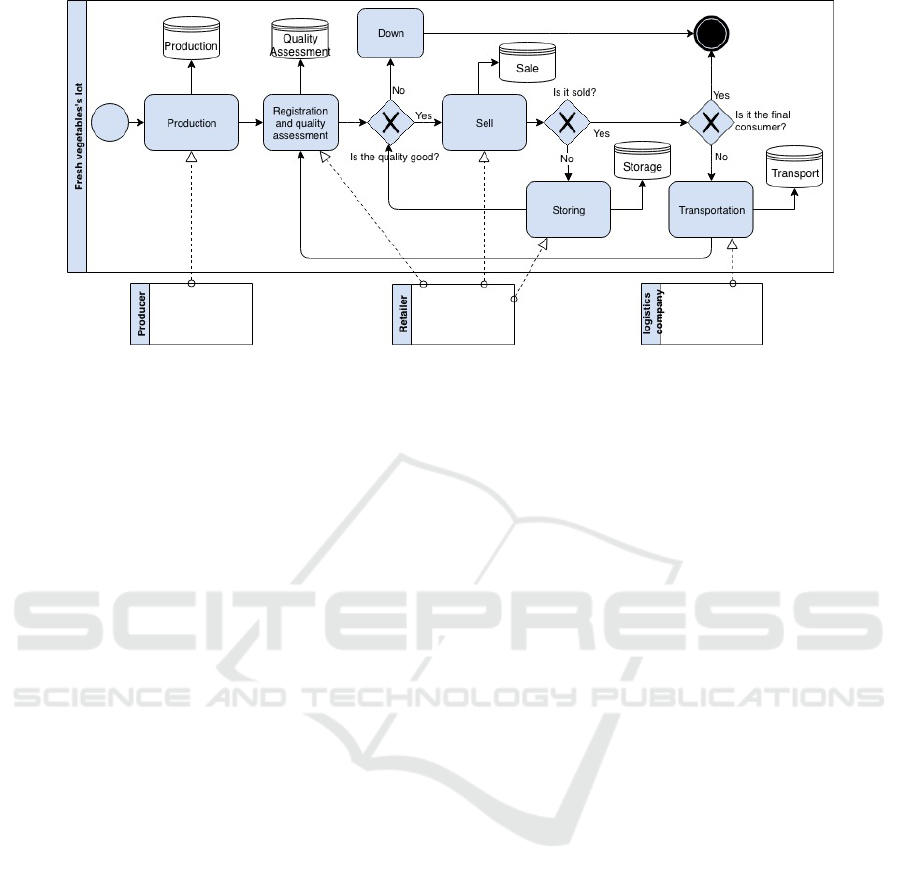

Figure 1: Value chain process for fresh vegetables.

3.1 Fresh Vegetables

Fresh vegetables, like fresh sardines, fresh milk or

other fresh food products, have several conditioning

factors for transport and storage. The fresh vegeta-

bles BP model is represented in Figure 1. In a value

chain of fresh vegetables, major producers, typically

owning their own brand, register and control the in-

formation about harvesting (activity Production in the

Figure 1), and assess, control and register the products

quality (Registration and Quality Assessment) before

selling them (Sell) to retailers. In these cases, the pro-

ducers are responsible for providing all that informa-

tion. Smaller producers, typically deliver their prod-

ucts in an agricultural cooperative or producers’ as-

sociation, which is responsible for registering infor-

mation about producers, products, and quality assess-

ment, and to sell products to retailers.

After being sold, products’ lots are usually trans-

ported to other sites. The information about who

transports and under what conditions the product is

transported must be stored. This information may be

provided by the transporter itself, but typically it is the

operator who receives the product that evaluates the

products’ lots quality conditions after the transport.

When products’ lots are received by a new owner,

this registers and assesses the products’ quality, be-

fore storing, transforming, or selling them. If, any-

time, a product’s lot quality is not acceptable, that

lot is downed. Information about storage conditions

(dates, cleaning conditions, temperature, etc.) must

also be registered. Products sold to the final customer

end their path through the value chain.

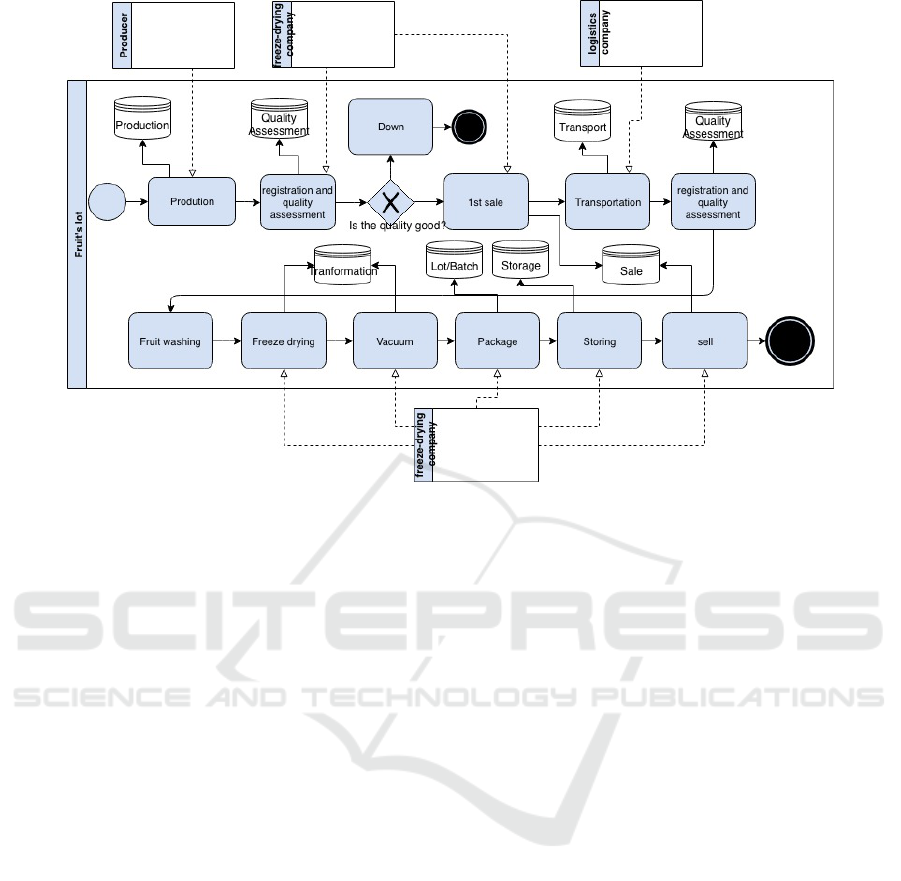

3.2 Freeze-dried Apples

Freeze-drying is a form of drying that removes all

moisture with almost no effect on a food’s taste. In

freeze-drying, food is frozen and placed in a strong

vacuum. The water in the food then sublimates. This

example deals with freeze-dried apples. The process

begins in the orchard in the production of apples (see

Figure 2). Once again, there are big and small produc-

ers. Major producers negotiate directly with industry,

while smaller ones deliver their products in associa-

tions or farmers cooperatives, responsible for control-

ling the quality and negotiating with industry. After

being sold, the apples are transported. The conditions

under which they are transported are always checked.

In any case, whenever apples arrive in the freeze-dried

factory plants, apple lots are received and registered,

and the quality is checked again before being submit-

ted to the transformation. A set of activities are exe-

cuted to obtain the final product. First the apples are

washed, then are sliced and freeze-dried, then pass

through vacuum and finally are packed. After packag-

ing, packet lots of sliced freeze-dried apples are stored

and wait their turn to be sold.

For enabling traceability, it must be possible to

know which new lots of freeze-dried apples came

from which previous lots of fresh apples. In other

words, lots of fresh apples may be transformed into

one or more lots of freeze-dried apples. In fact, a

given lot may be partially sold for a retailer, and par-

tially sold for a restaurant, and even partially sold

for being transformed. And industrial transformation

processes, such as freeze-drying apples, will create

lots of products from previous lots of fresh apples.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

288

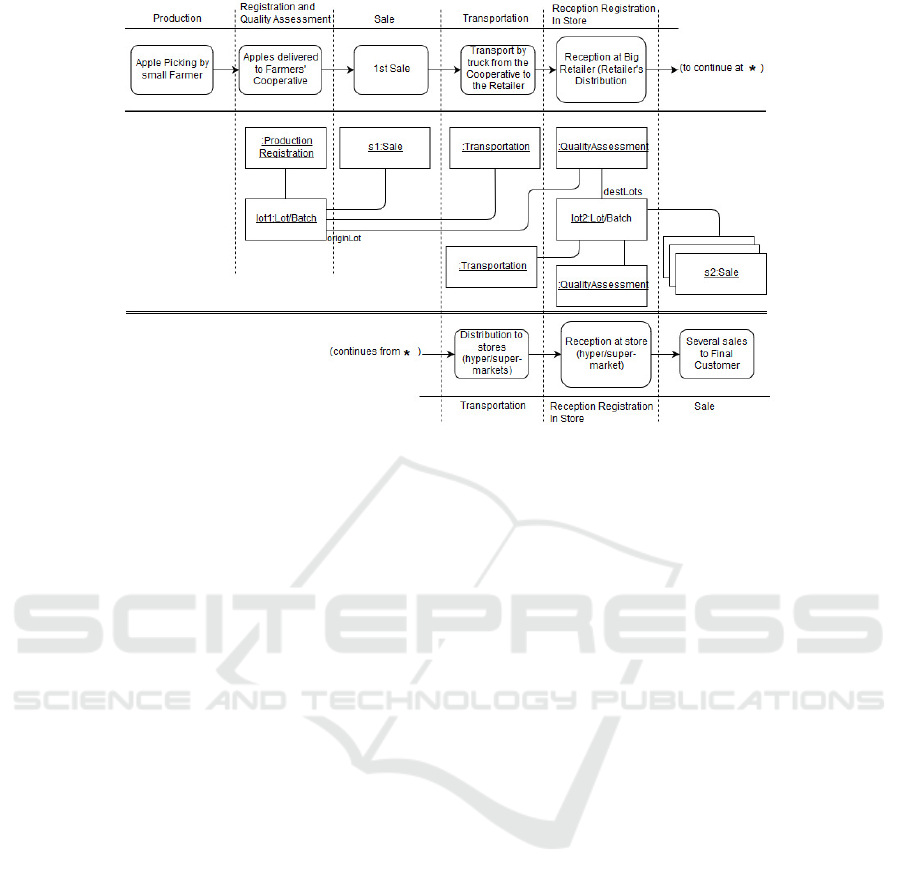

Figure 2: Value chain process for freeze-dried apples.

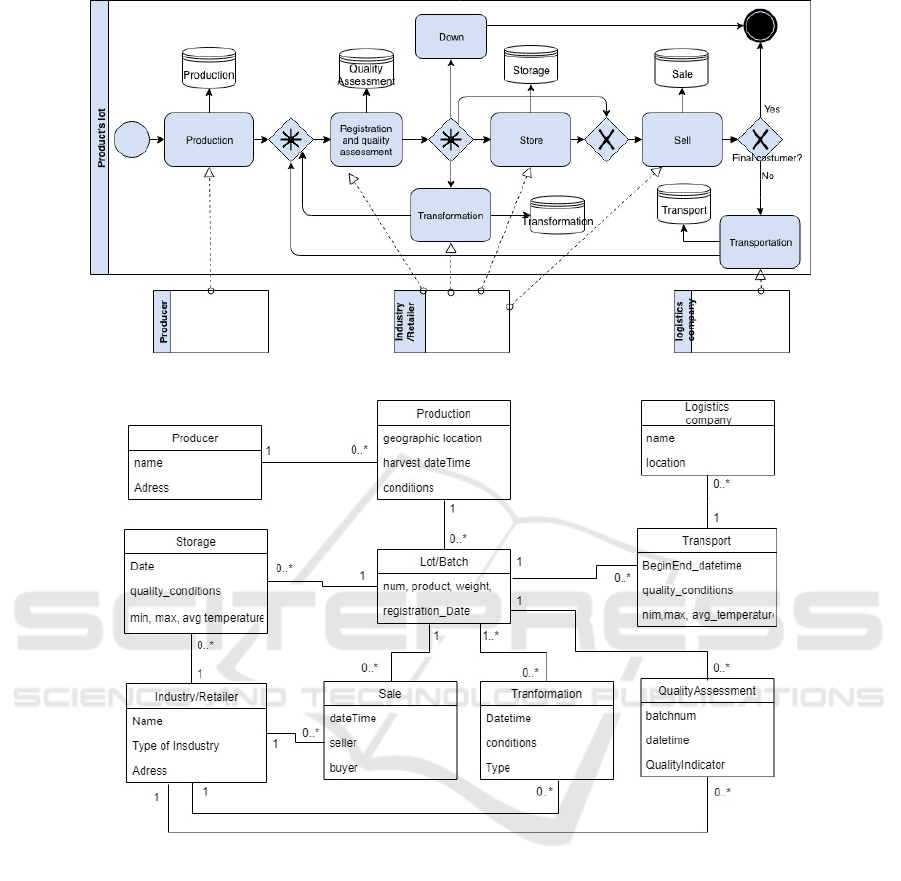

3.3 Food Value Chain’s Integrated

Process

The model of a BP at value chain level, represented in

Figure 3, serves as a pattern for representing any food

value chain inter-organizational collaboration space,

for enabling the traceability and quality monitoring of

products. In this BP model, six main activities have

been identified: Production, Registration and Quality

Assessment, Sell, Store, Transportation and Transfor-

mation. Additionally, there is activity Down, which is

executed if the product lot is spoiled or deteriorated,

or its validity date is expired.

With the exception of the Production and Down

activites, which may only happen once per each prod-

uct lot, every other activity may happen several times

in the product lot lifespan.

The value chain starts in the producer, where in-

formation about production (fishing, harvesting, fruit

picking, etc.) must be gathered. This information may

be provided by the producer itself (major producers)

or by associations of producers or agricultural coop-

eratives for small producers. Products are, then, reg-

istered and have their quality assessed.

As we may see in the process represented in Fig-

ure 3, after the registration and quality assessment, a

product lot may be sold or stored or transformed. Af-

ter each of these activities, the product lot is received

and its quality assessed. It may stay within this itera-

tion of activities during some time.

When a product lot is subjected to various pro-

cessing stages, the quality is verified at the end of

each stage (transformation task). The quality of the

product is assessed every time the product suffers a

transformation, a storage or a transportation. Some

of those times new lots are created and registered (as

is the case of transformation). Usually, after being

stored, a lot of product is sold. And, after being sold,

if the buyer is the final consumer, the process ends,

otherwise the product may be transported to the pur-

chasing organization, and that event must be regis-

tered for tracing purposes.

Transformation processes, together with the iden-

tified fresh products value chain’s activities, are rep-

resented in the Food Value Chain Integrated Business

Process for product traceability and quality monitor-

ing (see Figure 3). This comprises the value chain ac-

tivities (corresponding to value chain operators’ busi-

ness processes) of both the fresh products and the

transformed products. Note that, despite each value

chain activity corresponds to a business process in

the value chain operator that is responsible for it, in

the interorganizational traceability business process

model, in Figure 3, each activity refers to the gath-

ering of information from the process with the same

name. It is this information, gathered in a common

shared integration platform, that will enable prod-

ucts traceability and quality monitoring along the full

value chain path of each product lot.

Despite the traceability and quality data being di-

rectly persisted in the interorganizational space in the

A Food Value Chain Integrated Business Process and Domain Models for Product Traceability and Quality Monitoring: Pattern Models for

Food Traceability Platforms

289

Figure 3: Value chain integrated process model.

Figure 4: Derived domain model.

value chain, the data itself must be communicated by

the involved chain operator’s relevant process. Thus,

each activity can be seen as a value chain event.

4 DOMAIN ENTITIES MODEL

This section presents the domain model to support the

integrated process for traceability and quality moni-

toring in food value chains. In the next subsection,

we apply the approach presented in (Cruz et al., 2012;

Cruz et al., 2015) to derive a default domain model

from the integrated business process model presented

in subsection 3.3. Then, in subsection 4.2 we refine

the domain model to obtain a pattern domain model

that supports integrated platforms for traceability and

quality monitoring in food value chains.

4.1 Deriving the “Default” Domain

Model

In (Cruz et al., 2015) an approach has been presented,

to derive a domain (data) model by aggregating all the

information about persistent data that can be extracted

from business process models. In summary, in that

approach (Cruz et al., 2012; Cruz et al., 2015):

• A participant in the business process model gives

origin to an entity in the domain model;

• A data store also gives origin to an entity;

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

290

Figure 5: Refined domain entities model.

• The relation between entities is derived from the

information exchanged between participants and

the activities that operate the data stores, and from

the information that flows through the process.

• The entity that represents the participant repre-

sented by the main lane (pool) is related with

all entities in which information is stored (repre-

sented as data stores).

• Entities representing external participants that

send messages to activities that store information

in a data store are related with the entity that rep-

resents that data store.

By applying the approach presented in (Cruz et al.,

2012; Cruz et al., 2015) to the final integration busi-

ness process model (represented in Figure 3) we ob-

tain the domain model presented in Figure 4. In this

derived domain model, the entity Lot/Batch is de-

rived from the main lane (Products lot), after renam-

ing. The entities Producer, Industry/Retailer, Logis-

tics Company are derived from the external partici-

pants with the same name. The entities Production,

Quality Assessment, Sale, Lot, Storage, Transport

and Transformation are derived from the data stores

with the same name.

Messages sent by external participants to the ac-

tivities represented in the main lane, represent the in-

formation received by the activity that needs to be

stored (represented by the data store). This way, in

the domain model, the entity that represents the data

store is related with the entity that represents the ex-

ternal participant that sends the message (Cruz et al.,

2012; Cruz et al., 2015). Following this approach:

• A Producer, responsible for a Production, sends a

message to the activity that stores Production in-

formation, so entities Producer and Production are

related. The Producer may execute this process

several times so the relation is one to many.

• Store, Sell and Transformation are responsibility

of Industry/Retailers;

• Transport information is sent by the logistics com-

pany (or by the truck or driver), so entities Trans-

port and Logistics Company are related.

• Both logistics companies and Industry (tranfor-

mation companies, such as canning industries)

send information about quality assessment, stor-

age and sales, so entities Logistics Company and

Industry are related with all those entities.

• Entities Production, Transport, Storage, Sale,

Transformation and Quality Assessment are re-

lated with entity Lot/Batch because the activities

that store information in the corresponding data

stores are executed inside the main lane (in the

main pool) and according to (Cruz et al., 2012;

A Food Value Chain Integrated Business Process and Domain Models for Product Traceability and Quality Monitoring: Pattern Models for

Food Traceability Platforms

291

Figure 6: Fresh Apples from Small Farmer to Big Retailer.

Cruz et al., 2015), when a participant is respon-

sible for an activity that writes information in a

data store, the entity that represents the participant

must be related with the entity that represents the

data store.

The information about transport, quality assess-

ment, sale and transformation may be stored any num-

ber of times and the information may be provided by

different value chain operators.

The next section refines this model for a better

object-oriented structuring, and with reusability in

mind.

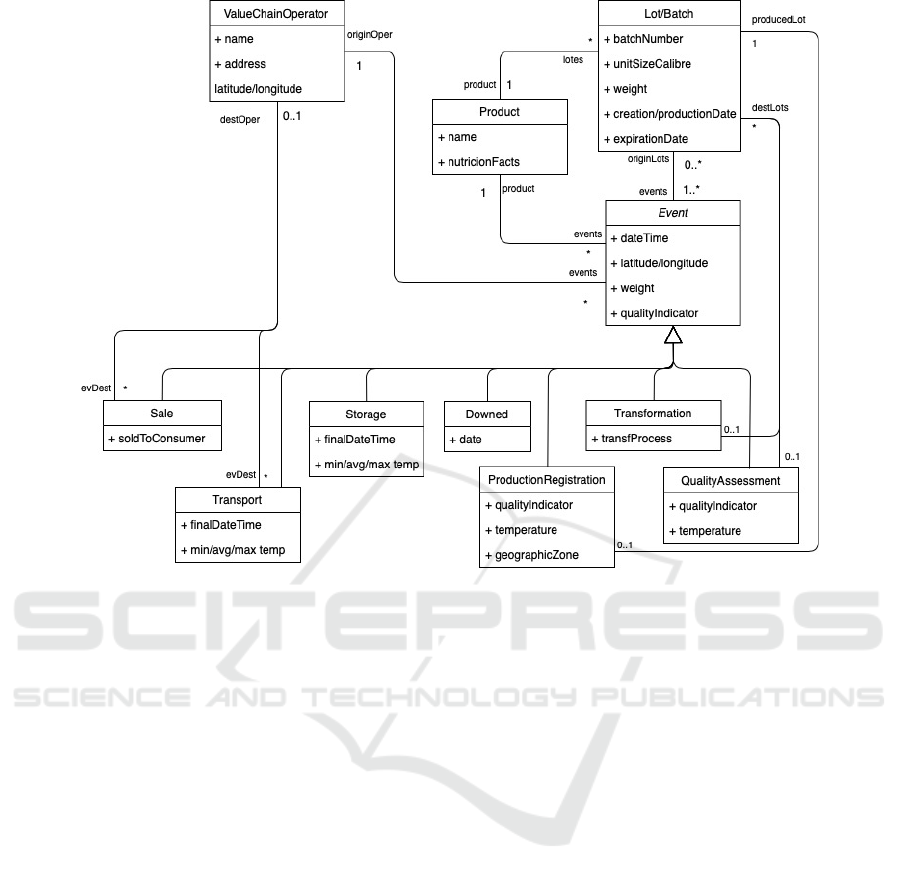

4.2 Refining the Domain Model

The derived domain model (Figure 4) is a default

model that may be now used for refinement into

a complete and fully understandable object-oriented

domain model. This section illustrates the refinement

of the derived model.

First, let’s remember that:

1. Producer, Industry, Retailer and Logistics Com-

pany are all Value Chain Operators;

2. Production, Quality Assessment, Sale, Storage,

Transport and Transformation are Value Chain

Events (that gather traceability and quality infor-

mation about product Lots);

3. Small producers do not register their production.

Only when delivered to a farmers association or

cooperative the production is wheighed and the

product lot is registered.

4. When receiving fresh products, some value chain

operators wheight and assess the quality of re-

ceived products and create/register a new product

batch, with a new reference or Lot number. This

new lot reference must be associated to the previ-

ous lot reference, for traceability.

5. After a transformation process, new lots of prod-

ucts may be created, referring to the new trans-

formed product.

6. Lots are allways about a product. E.g.: Lot of

fresh sardines, canned sardines, frozen sardines.

From item 1, above, in the refined Domain Model

(Figure 5) we can then find a ValueChainOperator

entity, which is an abstract class representing any

value chain operator: Producer, Industry, Retailer

and Logistics Company. These are then subclasses

of ValueChainOperator (not represented in the di-

agram). We have, also, from item 2, an Event en-

tity, which is an abstract class representing any event

about Lots in the value chain. By value chain event,

we mean any activity that leaves a trail of information

on the platform. Namely, Production, Quality Assess-

ment, Sale, Storage, Transport and Transformation,

which are represented as subclasses of Event.

In the figure, originLots represents the lots that

are associated to the event. A ProductRegistration

is where a value chain operator (a Producer, which,

by 3 may be a major producer or a producers’ as-

sociation) typically creates a new Product Lot. It

doesn’t have an origin lot, having a producedLot in-

stead. Additionally, there are events that may im-

ply the creation of new lots from previous ones,

namelly Trans f ormation (from item 5, above) and

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

292

QualityAssessment (from item 4). These events

may be associated to the set of newly created lots

(destLots). In the refined diagram (Figure 5),

the many-to-many relation between Lot/Batch and

Trans f ormation, from the diagram in Figure 4,

has given place to a many-to-many relation from

Lot/Batch to Event (a lot may have many events;

and, an event may have many original lots), and a

one-to-many from Trans f ormation to Lot/Batch (a

transformation may create several new product lots).

Event QualityAssessment has been given the same lot

association properties as Trans f ormation. All other

events have one and only one original Lot.

A product lot is always about a product (see item

6 above, and entity Product in the refined diagram).

A Lot’s Sale or Transportation may be associ-

ated to a destination value chain operator (destOper).

A Lot may yet be stored (event Stor age) during an

amout of time or it may be shut down (Downed) if it

is deteriorated or its validity date has been reached.

The diagram in Figure 5 presents only the main

attributes of each entity class. The real appropriate

attributes depend from case to case, from which prod-

ucts’ lots properties are being monitored and traced in

each case. The next section presents three case stud-

ies for validating the presented business process and

domain models.

5 VALIDATION

In this section we validate our resulting models

through three exploratory case studies. Figures in this

section are organized into three lines where, the first

line contains the events that happen, from the value

chain integrated process. The second line explains the

case study situation from the point of view of each

operator. And, the third line shows an object dia-

gram with objects created by the traceability platform,

when the events happen.

Fresh Apples from Small Farmer to Small Re-

tailer. In the first case, a small farmer produces

apples and delivers them to a farmers’ cooperative.

The cooperative, then, registers the production lot, as-

sesses the products quality and packs the apples for

being sold and transported to retailers. After being

received at small retailers’ stores, they put the apples

ready for sale. For reasons of space and simplicity of

the case, there is no figure for this situation. Here, the

original Lot makes its way until the final consumer.

At any point, it is possible to know the information

about the lot and all of its events, as long as the lot’s

packages at the several retailers bear the lot reference

or number, because all the events are linked to the

original lot.

Fresh Apples from Small Farmer to Big Re-

tailer. Figure 6 shows a similar case, but having

the apples’ lot sold to big retailers. These, typically

create lots in their ERP system, when ordering prod-

ucts from the suppliers. And then, when receiving

the supplied lots, they re-assign them to the lots they

had created before. In this case, then, when being re-

ceived by the retailer, the traceability platform instan-

tiates class QualityAssessment which allows to create

a new lot, enabling to trace between the original lot

and the newly created lot. After this event, all subse-

quent value chain events must refer to this new lot.

In this case, it is possible to know the information

about the last lot and all of its events because all the

events are linked to that lot. As events have a times-

tamp (dateTime), it is also possible to order the events

of the last lot and see that it has been created in a

QualityAssessment event associated to another origi-

nal lot, and, from there, trace all the information about

the original lot.

Fresh Apples from Small Farmer to Freeze-

drying Industry. In Figure 7, the situation depicted

refers to when fresh products are sold to industries

for being transformed. After the first sale, prod-

ucts are transported to a factory and their quality

is assessed and registered in the object instance of

QualityAssessment. Then, after being submitted to

the industrial process, the resulting lot is registered

and has its quality assessed. This creates an instance

of Trans f ormation, which alows to associate the re-

sulting lot to the previous lot of the original fresh

product. In this case, the resulting lot will refer to

a new product (freeze-dried apples, not fresh apples).

In this case it is possible to trace back to the original

lot, from the reference of the last created lot.

6 CONCLUSIONS

For coping with the growing need of food prod-

ucts traceability and quality monitoring, this paper

presents a pattern business process model and a corre-

sponding pattern domain model derived from a set of

situations observed in food value chains. In the pro-

posed food value chain business process model, seven

activities have been identified. These activities cor-

respond to events in the value chain where informa-

tion must be delivered for an integrated traceability

platform, which lies in the space between value chain

operators. This information enables to know when,

where and how each product lot has been treated and

who participated in the process.

The proposed domain model has been obtained

A Food Value Chain Integrated Business Process and Domain Models for Product Traceability and Quality Monitoring: Pattern Models for

Food Traceability Platforms

293

Figure 7: Fresh Apples from Small Farmer to Freeze-drying Industry.

from the pattern BP model in two steps. First, a de-

fault domain model has been derived from the pattern

BP model by using the approach presented in (Cruz

et al., 2012; Cruz et al., 2015). Then, the derived

domain model has been refined for improving model

structure and reusability.

Three case studies have been presented to illus-

trate the approach. The two pattern models may now

serve as template models for designing traceability

platforms for food value chains. The entities’ at-

tributes, in the domain model (Figure 5), are not com-

plete. Their completion depends on the information

that needs to be monitored and traced, in each real

case traceability scenario.

The models obtained in this work are being used

and adapted to a fishery products value chain, for

quality monitoring and traceability. Future work will

also apply these to other products value chains.

REFERENCES

22005:2007, I. (2007). Traceability in the feed and food

chain. Technical report, Int’l Standards Organization.

Bevilacqua, M., Ciarapica, F., and Giacchetta, G. (2009).

Business process reengineering of a supply chain and

a traceability system: A case study. Journal of Food

Engineering, 93(1):13 – 22.

Cruz, E. F. and da Cruz, A. M. R. (2018). Deriving inte-

grated software design models from BPMN business

process models. In Proceedings of ICSOFT 2018 - Vol

1, pp 571–582. INSTICC.

Cruz, E. F., Machado, R. J., and Santos, M. Y. (2012). From

business process modeling to data model: A system-

atic approach. In QUATIC 2012, Thematic Track on

Quality in ICT Requirements Engineering, U.S.A., pp

205–210. IEEE Computer Society.

Cruz, E. F., Machado, R. J., and Santos, M. Y. (2014).

Derivation of data-driven software models from busi-

ness process representations. In 9th International

Conference on the Quality of Information and Com-

munications Technology (QUATIC2014), pages 276–

281. IEEE Computer Society.

Cruz, E. F., Santos, M. Y., and Machado, R. J. (2015). De-

riving a data model from a set of interrelated business

process models. In 17th International Conference on

Enterprise Information Systems, pages 49–59.

Dabbene, F. and Gay, P. (2011). Food traceability systems:

Performance evaluation and optimization. Computers

and Electronics in Agriculture, 75(1):139 – 146.

Folinas, D., Vlachopoulou, M., Manthou, V., and Manos, B.

(2003). A web-based integration of data and processes

in the agribusiness supply chain. In EFITA conference.

Ioannis Manikas, B. M. (2009). Design of an integrated sup-

ply chain model for supporting traceability of dairy

products. International journal of dairy technology.

Meroni, G., Baresi, L., Montali, M., and Plebani, P. (2018).

Multi-party business process compliance monitoring

through IoT-enabled artifacts. Information Systems,

73:61 - 78.

OMG (2011). Business process model and notation

(BPMN), version 2.0. Technical report, OMG.

Palma-Mendoza, J. A. and Neailey, K. (2015). A busi-

ness process re-design methodology to support sup-

ply chain integration: Application in an airline MRO

supply chain. International Journal Information Man-

agement, 35(5):620-631.

Regattieri, A., Gamberi, M., and Manzini, R. (2007). Trace-

ability of food products: General framework and ex-

perimental evidence. Journal of Food Engineering,

81(2):347 – 356.

UNION, E. (2002). Regulation (ec) no 178/2002 of the eu-

ropean parliament and of the council. Technical re-

port, Official Journal of the European Communities.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

294