Investigating How Social Elements Affect Learners with Different

Personalities

Wad Ghaban, Robert Hendley and Rowanne Fleck

School of Computer Science, University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, U.K.

Keywords:

Online Learning, Social presence, Performance, Satisfaction, Content Analysis.

Abstract:

Social presence is an essential factor in preventing learners from feeling isolation in online courses and in keep-

ing them connected. Some studies, however, point to the negative impact of the social elements in distracting

learners from concentrating on a course’s content. In this study, we investigated the influence on learners of

different personality types (using the big five model) of an optional chat added to an online learning platform.

The results show that there is a variation in the response of the learners based on their personality. However,

some personality classes spent the majority of time in the chat discussing off-topic subjects, such as fashion

or travel. Thus, although they enjoyed the features in the system, it negatively affected their knowledge gain.

We discuss the implications of our findings for adaptive online learning platforms in catering to learners with

diverse personalities.

1 INTRODUCTION

A social presence in online learning courses is be-

coming very important; it prevents learners from feel-

ing isolated and makes them feel that they belong

to the course and are connected to other learners

(Means et al., 2009). However, some researchers have

claimed that learners have different responses to so-

cial elements. Some learners find these elements en-

joyable and motivational (Kehrwald, 2008). Other re-

searchers argue that social elements are uninteresting

and cannot represent real human interaction (Cobb,

2009). Because of this difference in the perception of

social elements in online courses, we aimed to un-

derstand how different learners perceive social ele-

ments. In this research, we used personality as a

stable characteristic that can be used to describe hu-

man behaviour (Hogan and Hogan, 1989). Although

many personality theories can be considered to un-

derstand the effect of social elements, we adopted the

Big Five personality traits, a commonly used theory

to define personality. The Big Five personality traits

classifies personality into five dimensions: consci-

entiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism

and openness to experience (Hofstee, 1994), and dif-

ferent characteristics are associated with each type of

personality.

To understand the effect of access to chat on dif-

ferent personalities, We asked two groups of learners

to use one of two versions of a learning website, either

one that included chat or one that did not. Then, we

analysed the number and the type of messages from

learners with different personalities.

We hypothesised that learners with different per-

sonalities would have varied responses to access to

chat in online learning courses. Highly extroverted

and highly agreeable learners are usually described as

social, and they like to compete and collaborate with

others (Hofstee, 1994). Therefore, we hypothesised

that these learners would send a high number of mes-

sages, which may enhance their knowledge gain and

satisfaction. Highly conscientious learners are de-

scribed as always being organised and self-triggered

to complete their tasks (Hofstee, 1994). For these

learners, we hypothesised that these learners will use

the chat in appropriate way. These learners would re-

port the same level of knowledge gain and satisfac-

tion for both versions. Further, highly neurotic learn-

ers are described as having high emotional instability.

Because of this, we hypothesised that these learners

might not be satisfied with the chat and have lower

knowledge gain in the case of online learning courses

that included chat (Judge et al., 1999).

The results confirmed our hypothesis that there

is a variation in the response to the social elements

from the different personalities. Some learners en-

joyed using the chat to talk about many unrelated top-

ics, which negatively affected their knowledge gain.

416

Ghaban, W., Hendley, R. and Fleck, R.

Investigating How Social Elements Affect Learners with Different Personalities.

DOI: 10.5220/0007732404160423

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 416-423

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Other learners, such as the highly conscientious ones,

used the chat in an appropriate way, which did not

affect their knowledge gain.

This kind of research is important for understand-

ing the effectiveness of online learning platforms.

Learners’ interactions with online learning platforms

need to be observed and monitored by teachers. A

good teacher will then direct the interactions in a way

that ensures that every learner is enjoying and learn-

ing from them. This is what is expected from future

technologies: looking to the learners’ characteristics

and then directing their interactions in an appropriate

way that meets the learners’ expectations. However,

to achieve this, we need a strong understanding of the

effect social components have on learners by looking

to other factors, such as the learners’ moods and their

effective state.

2 BACKGROUND

Online learning was defined by (Richardson and

Swan, 2003) as any course that offers an entire cur-

riculum online and gives learners the ability to ac-

cess the materials anytime from anywhere (Anderson,

2008). (Richardson and Swan, 2003) noted that in on-

line learning, learners and teachers no longer have to

meet physically in order to share knowledge. These

courses are free from the constraint of time and space

(Ally, 2004). However, learners in online courses lack

face-to-face interaction and often miss the feeling of

belonging to a class, which may result in feelings of

isolation. Much research has suggested adding social

components to prevent learners from feeling isolated

and to keep them connected to one another (Means

et al., 2009).

2.1 Social Presence

(Garrison, 2007) noted that three elements must be

present for success in learning: teacher presence, cog-

nitive presence and social presence.

Social presence in online courses can be defined

as the degree to which participants in computer-

mediated communication can effectively connect

(Swan and Shih, 2005). (Tu and McIsaac, 2002) de-

fined social presence as the degree to which partici-

pants are aware of others in real interaction.

(Lowenthal, 2010) categorised social presence

into three categories: a) effective responses contain-

ing personal expressions of emotions and feelings, b)

cohesion responses containing expressions related to

building and supporting relationships, such as greet-

ings and c) interactive responses containing agree-

ments and disagreements. (Richardson and Swan,

2003) found that learners usually begin interactions

with a large number of cohesion responses. How-

ever, over time, the number of interactive responses

increased.

(Tu and McIsaac, 2002) noted that social presence

elements are an essential factor of learners’ success

in online courses. Social presence can occur in on-

line courses in many forms, such as chats, discussion

boards and emails (Aragon, 2003). Interactions be-

tween learners can contain texts, voice messages and

emojis (DeSchryver et al., 2009). Research shows

a strong correlation between a high social presence

and the learners’ outcomes (Richardson and Swan,

2003). (Swan and Shih, 2005) pointed out that learn-

ers who felt more comfortable using social elements

scored higher in their perceived learning. (Swan and

Shih, 2005) examined the effect of social elements on

learners’ satisfaction and achievement by asking 91

students to enroll in one of two versions of a course:

one with social elements and the other without. At

the end of the experiment, they measured how social

the learners were (high, medium or low) using a spe-

cial questionnaire. They also measured learners’ out-

comes and satisfaction levels. They found that learn-

ers who were more social were more satisfied and had

better perceived outcomes. These results were sup-

ported by (Richardson and Swan, 2003), who indi-

cated that the high use of social elements is a predictor

for learners’ satisfaction levels and outcomes. (McIn-

nerney and Roberts, 2004) pointed out that these ele-

ments can prevent learners from feeling isolated.

(Tu and McIsaac, 2002) showed that learners in

online courses need more information about other

learners’ profiles in order to have a more effective

interaction. However, (Garrison, 2007) argued that

some problematic issues exist pertaining to social ele-

ments in online courses, as text-based communication

cannot replace face-to-face expression and body lan-

guage. In addition, delayed responses from the learn-

ers may annoy some learners, whereas other learners

may feel insecure about computer-to-computer inter-

action. (Swan and Shih, 2005) interviewed learners

and asked them about their opinion of the social ele-

ments. Some learners described text communication

as ’cold’ and unlike physical interaction. Other learn-

ers stated that social elements motivate them to com-

plete the course. However, other learners mentioned

that social elements are not challenging or interesting.

Therefore, (Cobb, 2009) explained that the responses

of different learners towards social elements in online

courses varied. Thus, it is essential to understand how

learners with diverse personalities respond to social

elements in online courses.

Investigating How Social Elements Affect Learners with Different Personalities

417

2.2 Personality

Personality can be described as a set of character-

istics that describe how individuals think and feel

(Hofstee, 1994). (Hogan and Hogan, 1989) stated

that personality is consistent, and it may develop

over time. There are different theories used to

describe personality. For example, there are three

common theories of personality: Eysenck’s theory of

personality, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the

Big Five personality traits (Claridge, 1977). In this

research, the focus will be on the Big Five, which is

widely used in similar research (Wiggins, 1996).

Big Five Model. This theory is one of the most

popular theories used to explain and understand

personality (Wiggins, 1996). This theory classifies

learners’ personalities into five dimensions (types):

conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness,

neuroticism, and openness to experience. Table 1

summarises the traits associated with each personality

type.

Big Five Model Measurements. The most com-

mon measurements are the NEO Five-Factor Inven-

tory (the NEO-FFI) and the Big Five Inventory (BFI).

Many versions of the NEO-FFI have been developed.

Some of these versions have 240 questions, mak-

ing them time-consuming to complete (Laidra et al.,

2007). Thus, new short versions have been proposed.

However, these shorter versions suffer from reliability

problems. As a result, many researchers use the BFI,

which is considered more reliable than the NEO-FFI.

In addition, the BFI is free to use, and it exists in sev-

eral languages. Some versions are designed for chil-

dren and others for parents. In this research, we used

the BFI (46 questions) which was developed for chil-

dren (McInnerney and Roberts, 2004).

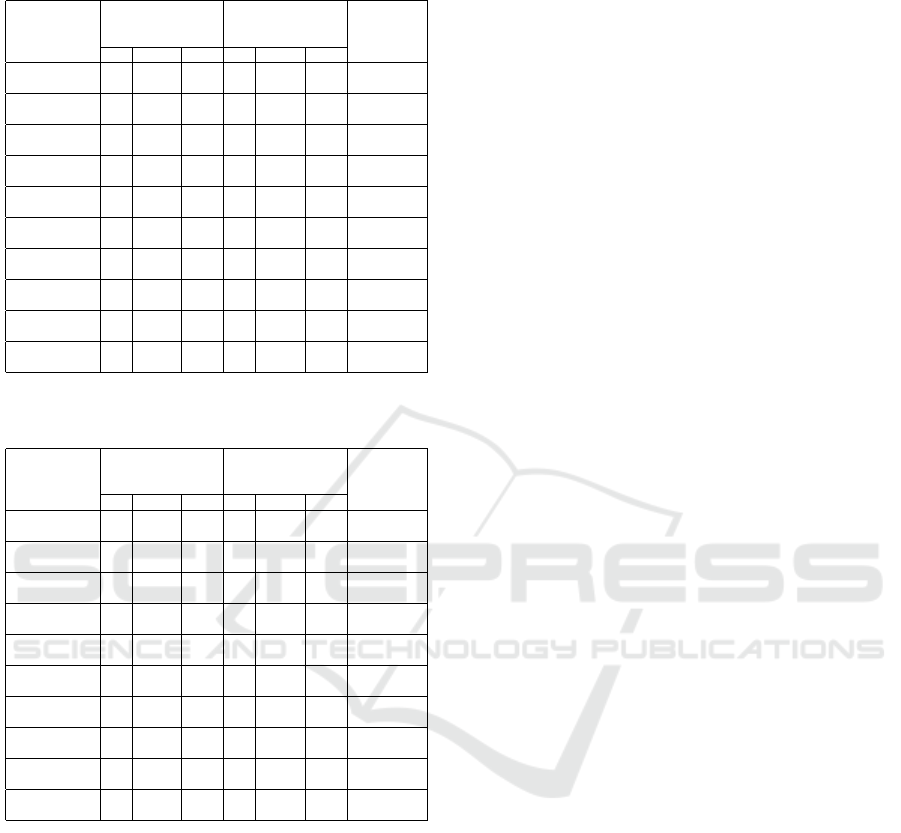

Table 1: A Summary of the Big Five Personality Traits

(adapted from (Wiggins, 1996)).

Personality Characteristics

conscientiousness

(a strong sense of purpose

and a high aspiration level)

Leadership skills, capability to make long-term

plans and often has an organised support network

Extroverted

(a preference for companionship

and social simulation)

Has good social skills and numerous friendships,

often participating in team sports and having

club memberships

Agreeable

(a willingness to defer to

others during interpersonal

conflicts)

Forgiving attitude and a belief in cooperation

Neurotic

( sadness, hopelessness

and guilt)

Low self-esteem and irrational

and perfectionistic beliefs

Openness to experiences

(a need for variety, novelty

and change)

Interested in different hobbies

and knowledgeable about foreign cuisine

3 METHOD

This study aims to investigate how different person-

alities interact with existing social components (chat)

in online learning system. In addition, we aim to

examine the effect of social interactions on learners

with varying personalities regarding their knowledge

gain and satisfaction.

Setup. We built an online learning system to teach

Microsoft Excel. The course consisted of 15 lessons

designed by the researchers, starting with simple top-

ics, such as drawing tables and visualising graphs.

From there, the course progressed to high-level top-

ics, such as mathematical and logical functions. We

built the website in two identical versions. One ver-

sion included a social component (chat); the other

lacked this component. In the version that included

chat, learners could use a button labelled ’Talk to a

friend’. When the learner clicked on this button, the

chat form appeared (Figure 1 ). In this version, learn-

ers believed that they were talking to another learner,

whilst, in fact, they were talking to a researcher who

was following a predefined script. We used this tech-

nique in order to control the conversation and to en-

sure that each learner experienced the same condi-

tions.

At the start, learners were required to set up a user-

name and a password. Subsequently, learners were

asked to supply demographic information, including

their age and gender. Learners were then asked to fill

in a BFI personality test. Finally, learners were asked

to fill in a pre-test related to the course itself.

Figure 1: A Screenshot of the Website Showing the Chat.

Participants. Before running the experiment, we

were granted ethical approval from four schools in

Saudi Arabia. Then, we sent a consent form to learn-

ers’ parents in which the school explained the pur-

pose of the experiment and informed them that all the

collected data would be anonymous and secure. The

learners and their parents were made aware that the

learners were free to dropout at any time.

After obtaining the consent forms, 194 learn-

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

418

ers (91 boys, 103 girls) participated in the experiment.

The Classification of Personalities. In this study,

we were concerned with understanding how differ-

ent personalities would deal with existing social com-

ponents. Accordingly, after obtaining the personality

score from the BFI personality test, we classified each

personality type into high, medium and low. Figure 2

shows an example of the classification of the extraver-

sion personality. The cut-off points were arbitrarily

chosen. To perform the classification, we drew a his-

togram that shows the values of the personality di-

mension on the x-axis and the frequency of the learn-

ers with that personality type on the y-axis. Then, we

classified learners lower than µ − σ as low. Learners

were assigned values for a specific personality trait

above µ + σ.

In this study, we believe there will be a strong ef-

fect on learners with extreme personalities. Conse-

quently, we only focus on the learners who are high

and low on each extreme of the personality type.

The value of the

personality

Histogram of Exp2TableTime2$op

Openness Personality

Frequency

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 5 10 20 30

!=2.6

!+"=3.9!-

"=1.31

Figure 2: The Classification of the Extraversion Personality.

Procedure. After obtaining the consent form, we

asked learners to fill in a demographic questionnaire,

the BFI personality test and the pre-test. Then, learn-

ers were divided equally into two groups: one group

used the website including the chat, and the other

group used the version without the chat. The two

groups were balanced in their age, gender, knowledge

level and personality score. Next, we asked learners

to use the website any time they liked; they were free

to dropout at any time.

After six months, most of the learners had either

dropped out or completed the course. Thus, after two

months, we asked learners to fill in a post-test that

related to the course and with the same number of

questions as the pre-test. Then, we calculated their

knowledge gain as:

Knowledge Gain = learners’ post-test results - learn-

ers’ pre-test results

We also asked learners to fill in a satisfaction

questionnaire. To measure their satisfaction, we used

the e-learner satisfaction tool (ELS) developed by

Wang (Wang, 2003). This tool consists of several

components, including a system interface, learning

content and system personalisation. The ELS tool

comprises 13 questions with a seven-point Likert

scale ranging from ’strongly disagree’ to ’strongly

agree’.

Hypotheses. In this study, we assume that there will

be variation in the response of the learners towards

the existing social elements. (Laidra et al., 2007) de-

scribe highly conscientious learners as always achiev-

ing well, and always making good progress. We hy-

pothesise that learners with this personality will use

the chat properly and that the conversation with the

learners will be on topics related to the course, most of

the time. These learners will always have high knowl-

edge gain and high satisfaction, regardless of whether

the system has social elements or not.

In contrast, highly extroverted learners, as de-

scribed by (Laidra et al., 2007), are likely to enjoy

making social relationships and interacting with oth-

ers. Thus, these learners will use the chat frequently,

and most of the messages will be off-topic. This may

enhance their knowledge gain and satisfaction.

Highly agreeable learners are usually described as

kind, and they like to collaborate with others. As a

result, we hypothesise these learners will spend their

time talking about the course and trying to help the

ones with whom they interact. This may enhance their

knowledge gain and their overall satisfaction.

4 RESULTS

In the study, we aimed to examine the influence of

the presence chat on learners with different person-

alities. For that, we looked to the number of mes-

sages sent from each personality (table 2). There was

a high number of messages sent from some personali-

ties compared to other personalities. Thus, we believe

it is interesting to find the kinds of messages received

from learners and to find if the kind of messages has

any effect on learners’ knowledge gain and their satis-

faction. Thus, we went to analyse the topic discussed

in the messages.

4.1 Content Analysis

In this study, we received almost 7,000 messages in

50 days from different learners with different person-

alities. Hence, as a first step, we cleaned our data

by removing all images and emojis. In the next step,

each message was independently coded by 2 annota-

tors, based on the message content. (We asked two na-

tive Arabic speakers to annotate each messages based

Investigating How Social Elements Affect Learners with Different Personalities

419

Table 2: The Number of Messages and the Number of Chats

Opened for Learners with Different Personalities.

Personality

Number

of learners

Number

of messages

Number

of chats opened

Average

(messages

per chat)

High

conscientious

22 1,238 53 23.3

Low

conscientious

18 1330 58 22.9

High

extraversion

22 3,317 109 30.4

Low

extraversion

25 343 26 13.19

High

agreeableness

16 1,076 44 24.4

Low

agreeableness

14 1305 36 36.25

High

neuroticism

18 978 46 21.2

Low

neuroticism

19 2486 94 26.44

High

openness

21 1,749 70 24.9

Low

openness

19 1654 55 30.7

Total 194 15476 591 26.1

on the codes presented in our codebook.) Table 3

shows the coding scheme for the messages. After that,

we measured the inter-rater reliability of our coding.

Then, we calculated the inter-rater reliability, which

is used to measure the level of agreement between

raters (Berelson, 1952) (Miles et al., 1994). The re-

sults show an inter-rater agreement of 97%.

Table 4 shows the number of messages in each cat-

egory sent from each personality.

Later, we looked in our data and tried to find

a common pattern in terms of learners’ personali-

ties. We found that highly conscientious learners of-

ten included a greeting in their messages and that

their messages generally remained on topic. Even

when conscientious learners discussed something off

topic, they were usually discussing the experiment

and what they needed to do to complete the experi-

ment. In contrast, highly extroverted learners often

sent multiple messages, began their messages with

greetings, and had off-topic discussions. For example,

they talked about football games and tourist places

to visit. Highly agreeable learners often used mes-

sages to introduce themselves and build relationships.

For example, some of these learners were asking if

they could have a real-time meeting. Highly open

learners preferred to talk about travel and fashion,

and they usually talked about their favourite places

to visit. These learners usually send links about the

course. Highly neurotic learners rarely opened the

chat dialogue. Most of their discussions were off

topic. They were complaining about their school and

homework. For example, one asked, ”Do you have

the same amount of homework as we have? I am tired

from all of it”. Figure 3 shows an example of the pat-

tern of messages from the different personalities.

Table 3: The Codebook Used to Define the Messages.

Code Definition Example

T

(Topic)

Messages relevant to the

topic (Microsoft Excel)

Which operation has priority in the

following formula in Excel:

3 ∗ 2 + 1/4

O

(Off-topic)

Messages related to any

topic other than Microsoft

Excel (e.g, fashion, travel,

weather)

Who was the winner of the last football

game between Al-Hilal and Al-Naser?

G

(Greeting)

Messages representing all

greetings, such as ’hello’,

or welcoming messages,

such as’ thank you’.

How are you? Where are you from?

GM

(Gamifica-

tion)

messages related to

gamification, such as

points and badges.

How many points and badges

did you collect?

Table 4: The Total Number of Messages (On-topic, Off-

topic, Greeting and Gamification).

Personality In-topic Off-topic Greeting

Game-

fiction

Total

High conscientious

N 300 574 321 43 1238

% 24.2 46.3 25.9 3.6 100

Low conscientious

N 148 507 639 36 1330

% 11.1 38.1 48.1 2.7 100

High extraversion

N 571 1612 864 270 3317

% 17.2 48.5 26.02 8.1 100

Low extraversion

N 54 152 123 14 343

% 15.7 44.32 35.8 4.08 100

High agreeableness

N 186 419 398 73 1076

% 17.5 38.9 36.9 6.7 100

Low agreeableness

N 164 599 443 99 1305

% 12.5 45.9 33.9 7.7 100

High neuroticism

N 98 414 433 33 978

% 10 42.3 44.3 3.3 100

Low neuroticism

N 454 1118 743 171 2486

% 18.38 44.9 29.8 6.8 100

High openness

N 265 759 638 87 1749

% 15.5 43.3 36.4 4.8 100

Low openness

N 258 765 480 151 1654

% 15.5 46.2 29.2 9.1 100

Total number of messages= 289

Total number of messages= 39

Total number of messages= 98

a)

b)

c)

Greeting

messages

In

-topic

messages

Off

-topic

messages

Gamification

elements

Figure 3: A Sample from the Pattern of Learners’ Conver-

sation for: a) Highly Extrovert, b) Highly Conscientious, c)

Highly Agreeable learners.

Additionally, to understand the effect of the num-

ber and the type of messages on learners with differ-

ent personalities, we looked to the knowledge gain

and the satisfaction of the learners. Table 5 sum-

marises the results of the learners’ knowledge gain

in both versions, while Table 6 summarises the re-

sults of satisfaction. Both tables show variations be-

tween personalities in response to the chat. For exam-

ple, highly neurotic learners were not satisfied with

the chat. However, highly extroverted learners are

shown to have the most learners affected by the chat.

These learners were satisfied with the presence of the

chat. However, this negatively affected their knowl-

edge gain, perhaps because learners were busy talking

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

420

Table 5: The Summary of the Results of the Knowledge

Gain for the Personalities.

Personality

Knowledge gain

in version includes

chat

Knowledge gain

in version without

chat

The benefit

of the chat

N Mean Sd N Mean Sd

High

conscientious

22 2.12 1.5 12 2.58 1.7 -0.46

Low

conscientious

16 2.5 0.45 13 2.15 1.86 0.35

High

extraversion

23 1 2.1 24 2.0 1.45 -1.04

Low

extraversion

22 2.04 1.9 12 1.3 1.55 0.71

High

agreeableness

16 1.2 2.4 17 2.17 1.81 -0.97

Low

agreeableness

15 1.06 2.3 12 1.91 1.44 -0.85

High

neuroticism

18 0.87 2.2 15 1.2 2.27 -0.33

Low

neuroticism

26 1.61 1.9 14 2.5 1.28 -0.89

High

openness

21 1 2.4 16 2.37 1.5 -1.37

Low

openness

26 1.34 1.5 14 1.64 1.9 -0.3

Table 6: The Summary of the Results of the satisfaction for

the Personalities.

Personality

Satisfaction in

version includes

chat

Satisfaction in

version without

chat

The benefit

of the chat

N Mean Sd N Mean Sd

High

conscientious

22 6.67 0.6 12 6.1 0.76 0.57

Low

conscientious

16 6.4 0.78 13 6.07 0.73 0.33

High

extraversion

23 6.64 0.58 24 6.1 0.49 0.54

Low

extraversion

22 6.6 0.53 12 6.01 0.73 0.59

High

agreeableness

16 6.34 0.9 17 6.2 0.96 0.14

Low

agreeableness

15 6.4 0.78 12 6.3 0.77 0.1

High

neuroticism

18 5.1 0.7 15 6.3 0.87 -1.2

Low

neuroticism

26 6.3 0.78 14 6.3 0.75 0

High

openness

21 6.5 0.78 16 6.3 0.83 0.2

Low

openness

26 6.3 0.87 14 6.3 0.8 0

and chatting, not concentrating on the course itself.

5 DISCUSSION

This study tried to investigate the behaviour of the

presence of the chat in an online learning course on

learners with different personalities.

Highly conscientious learners are described by

(Laidra et al., 2007), as those learners who always do

their job without the need for external factors. These

learners spent their time in the chat talking about the

course itself or about off-topic subjects that were still

related to the experiment. For example, they asked

each other how much time they needed to finish the

course or if they needed to contact someone when fin-

ishing an experiment. This may explain why these

learners were more satisfied in the version which in-

cludes the chat. Further, highly conscientious learn-

ers always have their own trigger to motivate them.

For that, these learners have the same level of knowl-

edge gain in both versions (including and not includ-

ing chat).

Highly extroverted learners spent their time chat-

ting about topics not offered by the course. This chat-

ting enhanced these learners’ satisfaction. However,

the results from the knowledge gain differ from those

in related work that suggest that the existence of so-

cial components enhances these learners’ outcomes

(Swan and Shih, 2005). The knowledge gain of the

highly extrovert learners was worse in the version in-

cluding chat. This result may be explained by the

fact that highly extrovert learners are easily distracted.

However, this result cannot be guaranteed and we may

need to run another study to validate this.

Highly agreeable learners ranked second in send-

ing the highest number of messages. Furthermore,

most of the messages were classified as a ’greet-

ing’. These learners tried to build a relationship with

their conversational partner. For example, they asked,

’How are you?’, ’Where are you from?’ and ’Can

we meet somewhere?’. The messages sent from this

personality adversely affected their knowledge gain.

These learners’ knowledge gain was better in the ver-

sion that without the chat. Further, the satisfaction of

these learners was almost the same in the both ver-

sions.

For the highly neurotic learners, we hypothesised

that these learners will be demotivated because of the

chat. These learners did not use the chat, and there

were very few messages sent from this personality.

Further, most of the messages sent from these highly

neurotic learners were from those students with very

high values in other dimensions, such as agreeable-

ness. This may be explained by the nature of the

study, as the chat was optional, and the learner had

to take the initiative.

Highly open learners were shown to have the same

level of satisfaction in both versions (including and

not including chat). However, the knowledge gain

was negatively affected by the chat. This might have

happened because of these learners’ lack of interest in

the chat. These learners are described by (Costa and

McCrae, 2008) as learners who are more likely imag-

inative and enjoy unusual events. Thus, the chat may

not interest these learners.

In our study, we noticed that some learners opened

the chat dialogue without starting a conversation.

Moreover, when learners started a conversation, they

Investigating How Social Elements Affect Learners with Different Personalities

421

were unsure with whom they were speaking. This

may have prevented learners from participating ac-

tively in conversations. (Cobb, 2009) pointed out that

learners speaking to anonymous entities may feel un-

comfortable participating in such conversations. In

addition, delays in sending and receiving messages,

for example, due to a poor Internet connection, could

have affected the learners’ behaviour.

Thus, because of the previous shortcomings, we

may need to conduct a further experiment with more

realistic chat. We can, for example, make the learn-

ers contact each other and record the conversation be-

tween them. In addition, we can repeat the same ex-

periment, but take the initiative to discern how differ-

ent personalities will respond.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Because of the lack of physical interaction be-

tween learners in online courses, many studies have

suggested incorporating social elements into those

courses to prevent learners from feeling isolated. In-

teractions with teachers and other learners can be

achieved using chats, discussion boards and emails

(DeSchryver et al., 2009). However, some research

has claimed that some learners do not prefer to talk

to others, while others may get distracted because of

these interactions (Laidra et al., 2007). Some learners

may also feel insecure in online interactions (Tu and

McIsaac, 2002). Because of these varied responses to

social components, we designed this study to inves-

tigate how different personalities respond to existing

social components, such as chat.

The results from our study confirm the variation of

the effect of chat on the different personalities. Some

learners enjoyed using the chat. Some personalities

spent their time talking about off-topic subjects rather

than the course, while others preferred to build rela-

tionships and introduce themselves. This variation in

the response to the chat affected learners’ knowledge

gain and satisfaction. For example, Some personali-

ties are not expected to show any difference in their

knowledge gain and satisfaction either with or with-

out the social element, such as highly conscientious

learners. However, other learners are more satisfied

where there is a social element. Meanwhile, some

learners have less knowledge gain where there is chat,

such as the highly extrovert learners. These learners

have the highest number of messages. Most of their

messages are about topics other than the course itself,

for example: fashion, travel and sport. To enhance the

knowledge gain of these learners, we may need to ob-

serve the behaviour of these learners, and then direct

the conversation back to the topic itself. For example,

if the learners start to talk about an off-topic subject,

one might say, ’This is okay, but let’s talk about the

course’.

This study provides insight into the type and num-

ber of messages sent by different personalities. How-

ever, in this experiment, only a few learners with

extreme personalities were included. In addition,

there was a positive correlation between personalities,

which may have resulted in bias. In this experiment,

the learners had to take the initiative and start a con-

versation; as such, some learners chose not to talk.

Thus, we could not examine the effect of the chat on

them. Furthermore, the researchers responded to the

learners, which may have resulted in delayed or unin-

teresting responses. Thus, further studies need to be

conducted to have a better understanding of the effect

of social components on learners. In this study, we

used personality as a stable characteristic related to

individuals’ behaviour. However, there are other char-

acteristics that may be considered (e.g. learners’ ef-

fective state, mood and learning style). After building

a good understanding about what is needed and liked

by each learner, we can build a system that provides

a dynamic place for learners’ conversations. This can

be done by controlling and directing the conversation

for some learners or by encouraging some learners to

interact more with others.

REFERENCES

Ally, M. (2004). Foundations of educational theory for on-

line learning. Theory and practice of online learning,

2:15–44.

Anderson, T. (2008). The theory and practice of online

learning. Athabasca University Press.

Aragon, S. R. (2003). Creating social presence in online en-

vironments. New directions for adult and continuing

education, 2003(100):57–68.

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication

research.

Claridge, G. (1977). Manual of the eysenck personality

questionnaire (junior and adult): Hj eysenck and sybil

eysenck hodder and stoughton (1975). 47 pp., together

with test blanks and scoring keys for junior and adult

versions. specimen set£ 1.80.

Cobb, S. C. (2009). Social presence and online learning: A

current view from a research perspective. Journal of

Interactive Online Learning, 8(3).

Costa, P. T. and McCrae, R. R. (2008). The revised neo

personality inventory (neo-pi-r). The SAGE handbook

of personality theory and assessment, 2(2):179–198.

DeSchryver, M., Mishra, P., Koehleer, M., and Francis,

A. (2009). Moodle vs. facebook: Does using face-

book for discussions in an online course enhance per-

ceived social presence and student interaction? In

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

422

Society for Information Technology & Teacher Edu-

cation International Conference, pages 329–336. As-

sociation for the Advancement of Computing in Edu-

cation (AACE).

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry re-

view: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence is-

sues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks,

11(1):61–72.

Hofstee, W. K. (1994). Who should own the definition

of personality? European Journal of Personality,

8(3):149–162.

Hogan, J. and Hogan, R. (1989). How to measure employee

reliability. Journal of Applied psychology, 74(2):273.

Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J., and Barrick,

M. R. (1999). The big five personality traits, general

mental ability, and career success across the life span.

Personnel psychology, 52(3):621–652.

Kehrwald, B. (2008). Understanding social presence in text-

based online learning environments. Distance Educa-

tion, 29(1):89–106.

Laidra, K., Pullmann, H., and Allik, J. (2007). Personal-

ity and intelligence as predictors of academic achieve-

ment: A cross-sectional study from elementary to sec-

ondary school. Personality and individual differences,

42(3):441–451.

Lowenthal, P. R. (2010). Social presence. In Social com-

puting: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applica-

tions, pages 129–136. IGI Global.

McInnerney, J. M. and Roberts, T. S. (2004). Online learn-

ing: Social interaction and the creation of a sense

of community. Educational Technology & Society,

7(3):73–81.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., and Jones,

K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in

online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online

learning studies.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., Huberman, M. A., and

Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An

expanded sourcebook. sage.

Richardson, J. and Swan, K. (2003). Examing social pres-

ence in online courses in relation to students’ per-

ceived learning and satisfaction.

Swan, K. and Shih, L. F. (2005). On the nature and de-

velopment of social presence in online course discus-

sions. Journal of Asynchronous learning networks,

9(3):115–136.

Tu, C.-H. and McIsaac, M. (2002). The relationship of so-

cial presence and interaction in online classes. The

American journal of distance education, 16(3):131–

150.

Wang, Y.-S. (2003). Assessment of learner satisfaction with

asynchronous electronic learning systems. Informa-

tion & Management, 41(1):75–86.

Wiggins, J. S. (1996). The five-factor model of personality:

Theoretical perspectives. Guilford Press.

Investigating How Social Elements Affect Learners with Different Personalities

423