In Reviews We Trust: But Should We?

Experiences with Physician Review Websites

Joschka Kersting, Frederik S. Bäumer

a

and Michaela Geierhos

b

Semantic Information Processing Group, Paderborn University, Warburger Str. 100, D-33098 Paderborn, Germany

Keywords: Trust, Physician Reviews, Network Analysis.

Abstract: The ability to openly evaluate products, locations and services is an achievement of the Web 2.0. It has never

been easier to inform oneself about the quality of products or services and possible alternatives. Forming

one’s own opinion based on the impressions of other people can lead to better experiences. However, this

presupposes trust in one’s fellows as well as in the quality of the review platforms. In previous work on

physician reviews and the corresponding websites, it was observed that there occurs faulty behavior by some

reviewers and there were noteworthy differences in the technical implementation of the portals and in the

efforts of site operators to maintain high quality reviews. These experiences raise new questions regarding

what trust means on review platforms, how trust arises and how easily it can be destroyed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Trust is the most important phenomenon in social

networks because it is necessary for the functionality

of such communities (Adali et al., 2010). Thus, trust is

defined as “a measure of confidence that an entity or

entities will behave in an expected manner” (Sherchan

et al., 2013). In social networks, trust is defined as “the

perceived trustworthiness of a typical member [in a

group] or the average trustworthiness of all members”

(Huang, 2007). Thus, trust delivers information about

who is eligible to receive and deliver information and

is therefore an interesting research issue and important

quality factor for the public (Emmert et al., 2013).

Furthermore, in our work, trust means to believe in

published reviews and willingly hand over data to other

entities (e.g., to the operator) in a social network such

as the operator. Moreover, trust usually is asymmetric.

In general, one party trusts another more and vice versa

(Sherchan et al., 2013).

In this paper, we investigate the trust factor on

Physician Review Websites (PRWs). These websites,

where patients can review the perceived quality of a

medical service, are an important phenomenon of the

Web 2.0 (Emmert and Meier, 2013). Physicians can

comment on reviews. PRWs offer additional services

for making appointments and provide medical

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0826-0144

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8180-5606

information by physicians for patients. However, the

true meaning of the relationship between patients and

physicians has been a complex research topic for ten

years (Ridd et al., 2009). Since patients’ privacy has

to be protected (Gal et al., 2008), there must be a

special trust mechanism in the community and even

on the platform. However, while the Web 2.0 boosted

review platforms, their quality is to be doubted. Apart

from privacy issues (Bäumer et al., 2017), there are

worries about content quality. For example, there is

the common threat of fake reviews: Reviews

published without a prior performed service, reviews

as revenge or published in order to harm Health Care

Providers (HCPs), to influence competition or for

other reasons than reviewing a performed service

(Luca and Zervas, 2016). However, there are many

scenarios possible, even system infiltrations (e.g.,

fake replies to reviews by non-HCPs) or mistakes

caused by PRWs themselves. These few samples put

the trust factor in the focus of our investigation as

users must trust reviewers, PRWs and HCPs in their

public actions. While there are known concerns from

the users’ point of view, it is important to evaluate

who exactly has to trust whom in order to employ a

working PRW providing a benefit. To further

investigate trust, we build a trust network that

includes trust relationships among several entities.

Kersting, J., Bäumer, F. and Geierhos, M.

In Reviews We Trust: But Should We? Experiences with Physician Review Websites.

DOI: 10.5220/0007745401470155

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (IoTBDS 2019), pages 147-155

ISBN: 978-989-758-369-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

147

We structured this paper as follows: In Section 2,

we summarize the relevant state of research. In order

to explain who has to trust whom and what issues

there are in the area of trust in PRWs, we explain our

PRW trust network in Section 3. In Section 4, we give

an insight into our experiences in working with

physician reviews, considering both the reviews and

the implementation of different PRWs. In addition,

we provide information on the areas in which we have

gained experience and what we would like to look at

in future work. We discuss previous experiences and

the effects on our work in Section 5 before we

conclude in Section 6.

2 STATE OF THE ART

So far, most patients do not challenge an HCP’s

opinion or treatment methods (Lu et al., 2018). In the

Web 2.0, patients started gathering their own

knowledge (McMullan, 2006), not only about HCP’s

performance but also about diseases. That means that

information from the Internet influences the patient-

physician relationship (Jacobson, 2007). Here, it can

be stated that self-information search strongly

influences the patient-physician relationship because

it reduces the information asymmetry. Patients can

turn themselves into informed patients but can also be

misinformed by the Internet (Lu et al, 2016). PRWs

are one source for this kind of information, since they

deliver not only ratings for HCPs, but also health care

information published by HCPs. For instance, the

Lithuanian PRW pincetas.lt

c

enables providers

to publish articles dealing with medical treatment

methods, research news or advice on staying healthy.

While some scholars tried to quantify the trust

relationship (Dugan et al., 2005), HCPs are still the

gate keepers because they possess the medical

knowledge obtained through an expensive and

enduring process. Patients are usually left without the

full picture (Lenert, 2010). Generally, consumers do

not have full access to valid information, while

information especially on PRWs must be doubted

(Eysenbach and Jadad, 2001). While the Internet

shapes the trust relationship, three possible reactions

by HCPs can be observed. HCPs react to the changed

relationship where patients gain their own knowledge

because so far, the knowledge was almost exclusively

on the HCPs side. One possible reaction is feeling

threatened, but delivering the expert knowledge,

another reaction is that HCPs work together with the

patients in order to find the right diagnosis or, another

possible reaction, HCPs help patients finding the right

information (McMullan, 2006). The here presented

facts demonstrate the factors influencing the patient-

physician relationship. When regarding patients as

customers, trust plays an utterly important role in

order to keep patients from visiting another HCP.

Trust can build customer loyalty and HCP reputation

is identified to be a dominant factor here (Suki, 2011).

While some studies deal with trust in patient-physician

relationships (Anderson and Dedrick, 1990; Chaitin et

al., 2003) other studies investigate trust in social

networks (Adali et al., 2010; Almishari et al., 2013; Ma

et al., 2018) or with health information on the Web

(Bernstam et al., 2005) and other deal with PRWs in

general (Emmert and Meier, 2013; Fischer et al., 2015;

Gao et al., 2012). In the following, we explain how

trust is built on PRWs and present our idea of trust

network for patient-physician relationships.

.

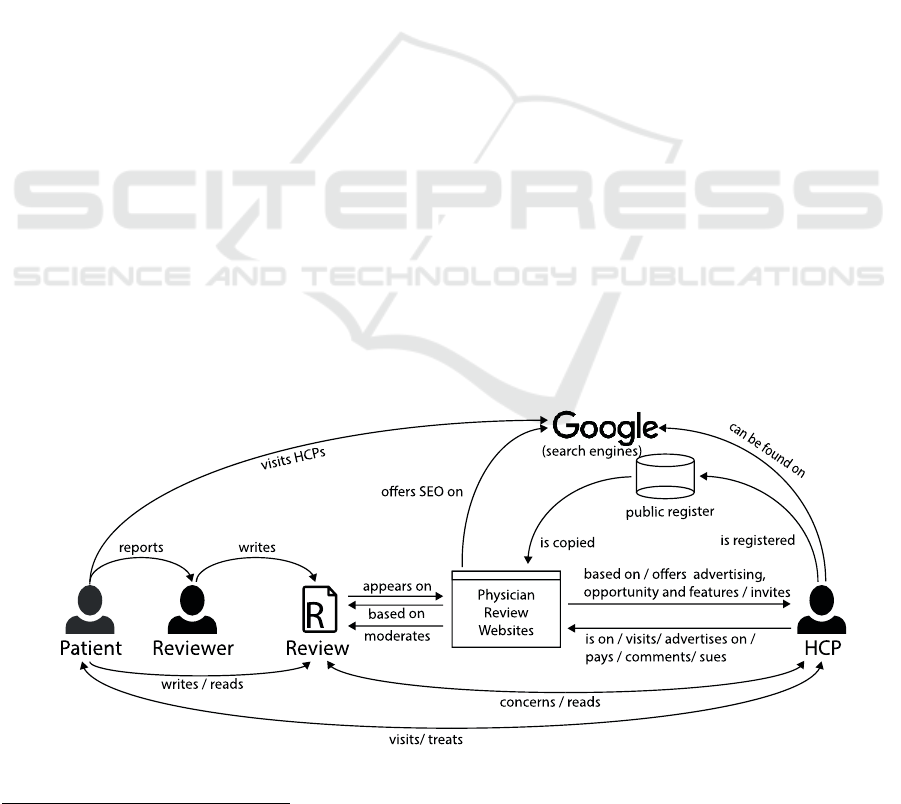

Figure 1: Trust Network Model on PRWs.

c

Available at https://www.pincetas.lt.

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

148

3 TRUST ON PHYSICIAN

REVIEW WEBSITES

This section shows our first findings how to establish

trust on PRWs. We show examples for fake reviewing

behavior and differences in the technical

implementation of PRWs, which we consider as

important quality factor. Since it is essential to

understand who interacts with whom, what is one’s

motivation, and what are the interdependencies

between the actors, we first outline our idea of how a

PRW trust network works in Figure 1. We designed

the trust network based on Jøsang et al. (2006). Our

study identifies several trusted entities such as

patients and reviewers, which both can be, but are not

necessarily, the same person (Bäumer et al., 2017).

Patients may report to related reviewers or write a

review on their own. Additionally, both patients and

reviewers read reviews, search for HCPs and visit

HCPs’ offices. While treatments still mainly take

place in the HCPs’ office, efforts are being made in

the field of telemedicine to enable medical

consultations via PRWs. An example therefore are

the efforts of the German PRW jameda.de, which

recently took over the German market leader for

video consultation (Jameda.de, 2019). Already today,

HCPs’ appointments can be arranged online on PRWs

– information is hereby made available to a third

party. Other entities are the PRWs and the HCPs.

Several actions can take place between them while

they influence and are influenced by these actions.

Generally, the PRW is the center of our network

because most of the covered interactions between

actors take place on it. However, since reviews form

the central business model of PRWs, they are (in most

cases) moderated by PRWs and rely on a predefined

rating schema. This rating schema is unique per

PRW, difficult to compare between PRWs (e.g.

different rating categories and scales) and can take

national peculiarities into account (e.g., on the

Lithuanian platform pincetas.lt, users can report

how much extra money was paid to an HCP). For our

study, we mainly used the Lithuanian PRW

pincetas.lt and the German PRW jameda.de

d

.

The moderation on PRWs takes place in the sense of

a fair use policy, the protection of HCPs and serves

the purpose of PRWs’ self-protection, as PRWs are

often sued. Since reviews as well as HCPs’ profiles

appear on well-known PRWs, they can be found on

search engines (e.g. Google) and improve the

visibility of HCPs on the Web. Similarly, negative

reviews can also damage HCPs’ reputation. Since

PRWs offer advertising opportunities and special

features for paying HCPs (e.g. publishing articles in

their name, place their profile prominently etc.), the

relation between HCPs and PRWs is also important

for the PRW business model. HCPs visit, advertise,

pay for, comment on or possibly even sue PRWs.

Figure 2: Distribution of Reviewers over Europe (pincetas.lt).

d

The website can be found at https://www.jameda.de.

In Reviews We Trust: But Should We? Experiences with Physician Review Websites

149

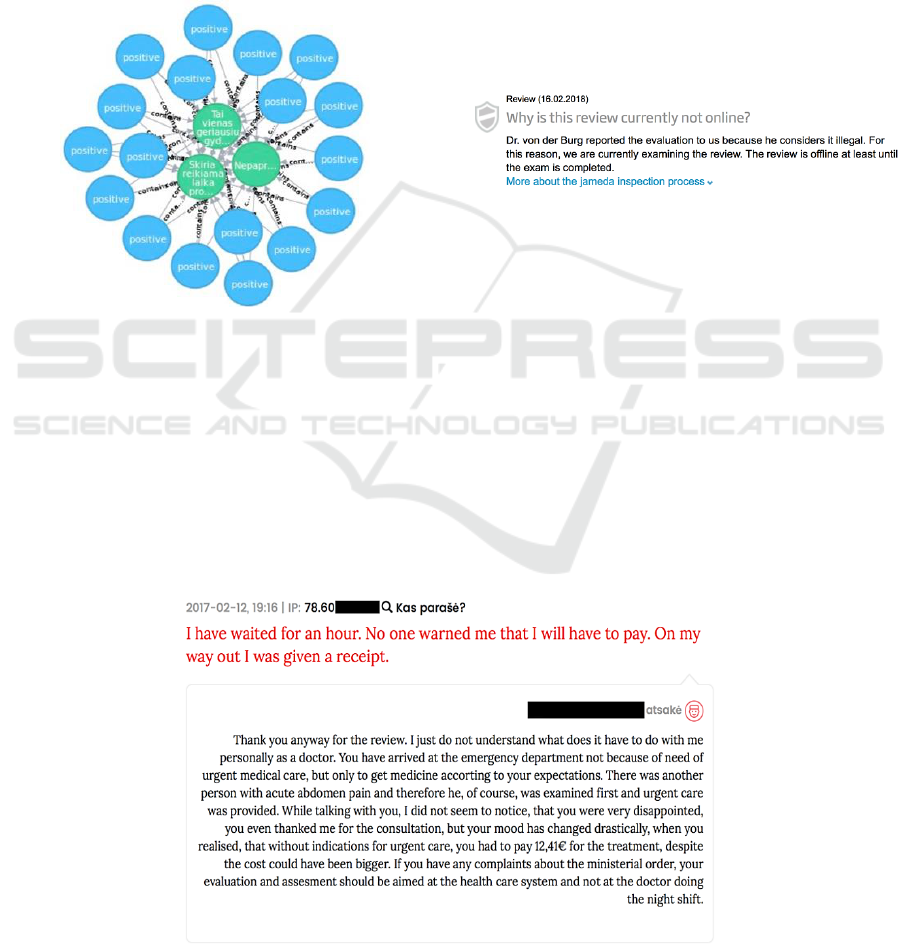

Figure 3: Review with IP Address and Comment by the HCP (Bäumer et al., 2018).

Figure 4: Review Text as Possible Threat to Anonymity.

Since PRWs often copy basic datasets from online

available data sources (e.g. physician databases,

telephone directories) without further consent of the

HCPs. Here, trust also means that HCPs have to trust

the PRW, that they delete defamatory and unfair

reviews. However, among all entities, there must be

trust to establish a working social network. Missing

trust results in disputes and issues such as fake

reviews. A former empirical study based on physician

review data from several European PRWs led to

several findings: Faulty reviewer behavior comes up

as fake reviews to (1) harm an HCP, (2) take revenge,

(3) gain advantages or (4) improve the PRW (e.g.

public perception as an active platform) (Bäumer et

al., 2017). The literature defines fake reviews as,

among other possibilities, posting a review for any

other reason than reviewing the performed service or

product (Horton and Golden, 2015). We regard

duplicate reviews as an obvious example for spam

because they are copied review texts that are then

published for several HCPs. We found examples for

this in the data (Bäumer et al., 2018). Besides, the

ratings are given in typical manner, i.e. only good

grades for every rating category (e.g. 5/5 stars) or

only bad grades (1/5 stars). We found different kinds

of noisy data, which we will discuss in the following.

4 TRUST FACTORS ON PRWS

When examining review texts, profiles and platforms,

we have noticed cases in which the trust of different

actors on PRWs was at risk. In the following, we

would like to present our observations on the different

trust factors and how they are influenced.

4.1 Trust of Patients

On PRWs, patients have the opportunity to share

experiences with HCPs and utter their own opinions.

It is also a way to change the balance in the HCP-

patient relationship for the benefit of patients.

However, it is obvious that negative comments on

medical services are not in the interest of HCPs and

that the relationship between the actors can

dramatically deteriorate. For this reason, patients

have a legitimate interest in ensuring their anonymity.

At this moment, they trust both possible reviewers

and the PRWs to protect their anonymity. This means,

for example, that PRWs show only necessary meta

data (e.g. no real names, IP addresses). Here, large

PRWs use review moderation procedures, which

filter private information to protect patients.

However, these efforts do not often go far enough, as

existing research in this area shows (Bäumer et al.,

2017). Meta data (e.g. location, date, insurance, age,

gender) in combination with information that is

disclosed in the review text provide a user profile that

allows the de-anonymization of patients, possible at

least for the HCP and the staff members (see Figure

9). In contrast, there are also PRWs that try to ensure

a fair use on the PRWs by reducing anonymity. For

example, the Lithuanian PRW pincetas.lt

deliberately displays IP addresses next to reviews that

have not been written by registered users (see Figure

3, translated from Lithuanian). While this can be

perceived as a measure against cyberbullying and

fake reviews, it is also a danger because geographical

information can be derived via the IP address. It is

also possible to identify public places, universities

and cafés where the reviewers are located (see Figure

2). In this example, a first look at the data shows that

some reviewers (2%) come from other countries

(countries most Lithuanians emigrate to

(International Organization for Migration, 2019)).

Figure 4 (translated from German) shows an example

that contains real names, information about the family

situation, etc. The question here is, of course, whether

the patients simply do not care about possible

consequences or whether this information was given

unintendedly (in these cases, protection mechanisms

of the PRWs should have to take effect).

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

150

4.2 Trust of Reviewers

Because of the aforementioned fact that reviewers are

not necessarily identical with patients (Geierhos and

Bäumer, 2015), they have to trust the patients’

reports. As reviewers are the legally liable persons

when publishing reviews, their trust relationship with

the patient is important. Furthermore, when dealing

e.g. with minors, soft factors like the personal

relationship and interpretation of a child’s report are

inevitable. The reviewer has to trust the PRW as it can

put him/her at legal danger, and it possesses his/her

private data. This is a serious privacy concern because

PRWs usually do not validate the personal identity.

While reviewing HCPs, the reviewer puts his/her

relationship with HCPs in danger when being the one

who negatively reviews for another person.

4.3 Trust of PRWs

PRWs trust their reviewers because there are usually

no boundaries for the registration to provide personal

identification on PRWs. However, some PRWs force

the users to confirm to be the treated person, i.e.

reviewer and patient should be the same person. In

this regard, observations have shown that this is not

always the case, especially when parents rate for their

children (Geierhos and Bäumer, 2015). Nevertheless,

PRWs trust their reviewers who are, next to HCPs,

the ones providing valuable content that make it

desirable for others to access the website. In our work

with reviews, we have identified patterns of unnatural

user behavior. In the following, we would like to give

an insight into the patterns that are hidden for normal

users of PRWs, since they do not have an overview of

the entire dataset when they are searching for HCPs.

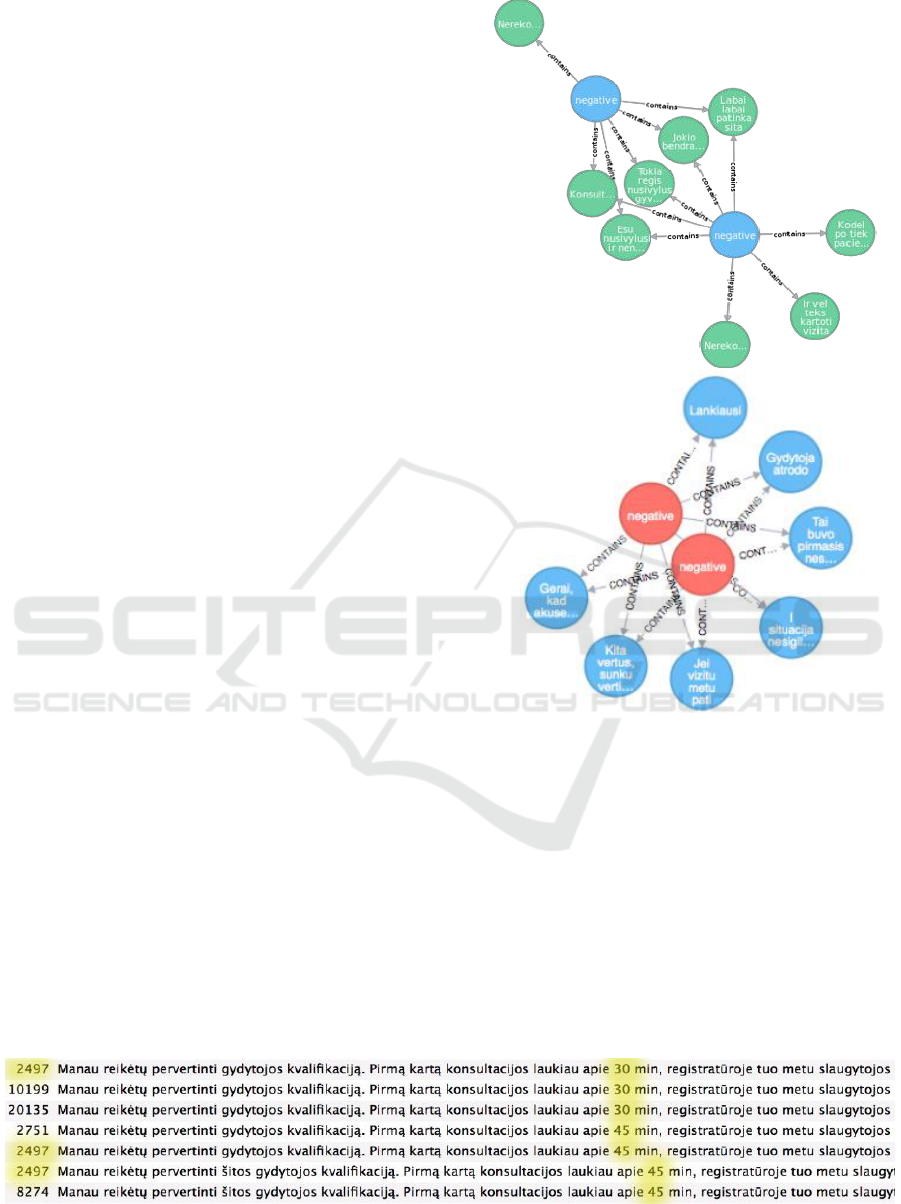

First of all, Figure 5 shows two examples that

represent duplicates, i.e. reviews with overlapping

content. Example A in Figure 5 shows a complete

duplicate in which two negative reviews (red colored

nodes) consist of seven identical sentences (blue

colored nodes) given to different HCPs. While such

complete duplicates can be found very quickly in a

database, it is almost impossible for users or rather a

matter of chance to become aware of such duplicates.

Figure 5: Negative Reviews consisting of the same

Sentences (Lithuanian), Examples A (top) and B (bottom).

Here, it is the responsibility of the PRW’s

operators to prevent such duplicates to keep the users’

trust in the review quality. However, the recognition

is more difficult in cases where reviews are not 1:1

duplicates but consist of mixed-up sentences taken

from other reviews (see Example B).

Example B shows two reviews (blue colored

nodes) that share five sentences (green colored nodes)

in total and still have their own sentences. This is a

phenomenon that often appears. For some phrases,

this is uncritical (e.g. “Thank you”, “Good doctor”).

Figure 6: Examples of Duplicates with marginal Changes (Bäumer et al., 2018).

In Reviews We Trust: But Should We? Experiences with Physician Review Websites

151

However, in the case of sentences that are very long

(e.g. 10-grams) and in which spelling and

grammatical errors are the same, intent must be

assumed. Even not only negative reviews are

affected, as shown in Figure 6. There are also cases

where a lot of reviews share the same sentences and

cases, where sentences are even used for different

sentiment statements. Such fake reviews destroy

users’ trust in the platform and therefore quality of

reviews, ratings and technical implementation of

PRWs (Filieri et al., 2015).

Figure 7: Positive Reviews sharing the same Sentences.

There are, however, duplicates with only small

differences. E.g. only numbers are changed, like

presented in Figure 7 (in Lithuanian). There, an HCP

with ID 2497 has four similar ratings (three visible in

the Figure). The first is from 2011, the others were

written within a shorter period in 2017. Three of four

reviews have the same IP address. These reviews are

either fake or real. As there is the same IP address

used, the reviewer could be a patient that visits a

doctor regularly and has the same opinion that is only

slightly changed. Anyhow, here is no explanation

delivered on why many HCPs have the same review

texts, as we experienced. Next to this, PRWs must

trust in HCPs when communicating with them. That

applies to advertisements booked by HCPs and to

complains. In short, HCPs can complain when they

feel not treated the right way. Such cases appeared in

the media, even when HCPs fear to be treated unfairly

(Nützel, 2018). PRWs have to balance their trust in

HCPs and reviewers in order to solve complains.

HCPs may feel unjustly rated while reviewers feel

justified in their opinion. However, in general, while

there is a direct relationship between patients and

HCPs, the PRW is the intermediary on the Internet

Figure 8: Sample Panel of Currently Blocked Review.

where involved parties may feel safe to say whatever

they have in mind. The trust of PRWs in reviewers

and HCPs has to be assumed as more unsafe due to a

missing personal relationship.

4.4 Trust of the HCPs

HCPs trust in PRWs and their patients. Generally,

HCPs can feel safe treating patients due to the

information asymmetry (Eysenbach and Jadad, 2001;

Lu et al., 2016). HCPs are the professionals while

patients are usually uneducated in health care

(Dickerson and Brennan, 2002). However, this may

lead to harsh judgements (and comments) on PRWs

Figure 9: HCP Response with Data Disclosure (translated from Lithuanian).

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

152

due to misinterpretations (see Figure 9). Besides,

HCPs have to trust in PRWs as they, regardless of

HCP’s will, may publicly make a profile available

and encourage patients to review HCPs. Furthermore,

HCPs must trust in PRWs to provide proper

information and identify spam or fake reviews as well

as insulting reviews. An example for the protection

by PRWs is given in Figure 8. Here, a PRW blocked

a review because it was reported by the rated HCP.

5 DISCUSSION

As is often the case, trust is essential for social

interaction – whether offline or online. PRWs

represent an interesting subject for research: While

PRWs are pure online service providers, patients and

HCPs also interact offline. However, as described

here, the question of trust aroused: “Who trusts whom

on PRWs?”. In the past, we acquired data from PRWs

to answer this question. Anyhow, as presented in this

paper, the relations are complex and not all entities

can be separated from another (e.g. reviewer and

patient). Many factors influence the relationships. For

example, the patients have less knowledge than

physicians (information asymmetry), while patients

are regarded as “oppressed” party (Dickerson and

Brennan, 2002). In conclusion, a complex network of

relationships is built in which one change affects

many entities. Therefore, we want to shed light on the

whole network by summing up possible relationships

and their characteristics.

But does it have to be taken so seriously? Aren’t

PRWs just other social networks where everything

can’t be taken seriously? We deny that. As we have

shown, the trust factor in the network also arises from

the various intrinsic motivations to participate in it.

Patients who share their experiences in good faith and

patients who get recommendations from these portals

trust PRWs. The PRWs’ business model is based on

positioning themselves as a professional contact point

for HCPs and patients and therefore a solid trust in

this business model must also be part of it. When it

comes to fake reviews, it should be mentioned that

reviews have undergone quality checks by most

PRWs before publication. However, there are quality

concerns that need to be tackled by the PRWs. In

order to support the development in this area, we

could make use of collected PRW data. Still, fake

reviews are hard to identify because, when writing a

review, the true intention is only known by the

reviewer himself.

As we presented a systematic approach to figure

out trust in PRWs, we lack some quantified basis.

This will be part of our future work. An idea fitting to

the complexity of a trust network are key

performance indicators measuring the current state of

the trust network. Our work presents thoughts that

will help researchers in future to investigate new

aspects concerning the medical sector. However, it

will be of great importance to not only formalize trust

relationships but to understand their true meaning and

current state. For this reason, future research should

investigate how trust between entities currently works

(based on reviews from PRWs). Here, our model

helps identifying relationships and assigning a state to

them. Generally, it will be an interesting finding how

well the relationships from our trust network are

working right now and over time. This provides a new

way of investigating the patient-physician

relationship apart from, e.g., opinion polls.

6 CONCLUSION

All in all, we created a trust network for PRWs that

can be used for a better comprehension of the

relationships on PRWs and comparable health-related

websites. We further discuss trust factors, i.e., who

has to trust whom to establish fully working PRWs in

the sense of social networks. We here identified

several weaknesses that lead to serious repercussions

in real life. We also showed several examples

extracted from PRWs. Further research enables us to

conduct a data-based investigation of the trust

network. We acquired exhaustive data bases of

several European PRWs and from the USA. We will

analyze the existence of relations and threats to them

while providing solutions to avoid such issues in

future. This, however, requires a partly redesign of

PRWs or the application of natural language analysis

tools. We answered the question who trusts whom

and why. In future work, this question can be

answered in a more detailed manner. Generally, we

expect a data-based analysis to be promising when

determining key performance indicators that may

provide information about the state of trust as well as

the corresponding relationships and threats to them.

REFERENCES

Adali, S.; Escriva, R.; Goldberg, M. K.; Hayvanovych, M.;

Magdon-Ismail, M.; Szymanski, B. K.; Wallace, W. A.

& Williams, G., 2010. Measuring Behavioral Trust In

Social Networks. International Conf. on Intelligence

and Security Informatics, IEEE, 150-152.

In Reviews We Trust: But Should We? Experiences with Physician Review Websites

153

Almishari, M.; Gasti, P.; Tsudik, G. & Oguz, E., 2013.

Privacy-Preserving Matching of Community-

Contributed Content Computer Security - ESORICS

2013: Proceedings of the 18th European Symposium on

Research in Computer Security, Egham, UK, 2013,

Springer, 8134, 443-462.

Anderson, L. A. & Dedrick, R. F., 1990. Development of

the Trust in Physician Scale: A Measure to Assess

Interpersonal Trust in Patient-physician Relationships.

Psychological Reports, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 67(3),

1091-1100.

Bäumer, F. S.; Grote, N.; Kersting, J. & Geierhos, M., 2017.

Privacy Matters: Detecting Nocuous Patient Data

Exposure In Online Physician Reviews. Proceedings of

the 23rd International Conf. on Information and

Software Technologies, Communications in Computer

and Information Science, 756, 77-89, Springer.

Druskininkai, Lithuania.

Bäumer, F. S.; Kersting, J. & Geierhos, M., 2018. Rate

Your Physician: Findings from a Lithuanian Physician

Rating Website. Proceedings of the 24th International

Conf. on Information and Software Technologies,

Communications in Computer and Information

Science, 920, 43-58, Springer, Vilnius, Lithuania.

Bernstam, E. V.; Shelton, D. M.; Walji, M. & Meric-

Bernstam, F., 2005. Instruments to Assess the Quality

of Health Information on the World Wide Web: What

Can Our Patients Actually Use? International J. of

Medical Informatics, 74(1), 13-19.

Chaitin, E.; Stiller, R.; Jacobs, S.; Hershl, J.; Grogen, T. &

Weinberg, J., 2003. Physician-patient Relationship in

the Intensive Care Unit: Erosion of the Sacred Trust?

Critical Care Medicine. Ovid Technologies (Wolters

Kluwer Health), 31(5), 367-372.

Dickerson, S. S. & Brennan, P. F., 2002. The internet as a

catalyst for shifting power in provider-patient

relationships. Nursing Outlook, 50(5), 195-203.

Dugan, E.; Trachtenberg, F. & Hall, M. A., 2005.

Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient

trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical

profession. BMC Health Services Research, Springer

Nature, 5(1).

Emmert, M. & Meier, F., 2013. An Analysis of Online

Evaluations on a Physician Rating Website: Evidence

From a German Public Reporting Instrument. Journal

of Medical Internet Research, JMIR Publications Inc.,

15(8), e157.

Emmert, M.; Meier, F.; Pisch, F. & Sander, U., 2013.

Physician Choice Making and Characteristics

Associated With Using Physician-Rating Websites:

Cross-Sectional Study Journal of Medical Internet

Research. JMIR Publications, 15(8), e187.

Eysenbach, G. & Jadad, A. R., 2001. Evidence-based

Patient Choice and Consumer health informatics in the

Internet age Journal of Medical Internet Research.

JMIR Publications Inc., 3(2), e19 .

Filieri, R.; Alguezaui, S. & McLeay, F., 2015. Why do

travelers trust TripAdvisor? Antecedents of trust

towards consumer-generated media and its influence

on recommendation adoption and word of mouth

Tourism Management, 51, 174-185.

Fischer, S. & Emmert, M. Gurtner, S. & Soyez, K. (Eds.),

2015. A Review of Scientific Evidence for Public

Perspectives on Online Rating Websites of Healthcare

Providers Challenges and Opportunities in Health

Care Management, Springer, 279-290.

Gal, T. S.; Chen, Z. & Gangopadhyay, A., 2008. A Privacy

Protection Model for Patient Data with Multiple Sensitive

Attributes. International Journal of Information Security

and Privacy, IGI Global, 2(3), 28-44.

Gao, G. G.; McCullough, J. S.; Agarwal, R. & Jha, A. K.,

2012. A Changing Landscape of Physician Quality

Reporting: Analysis of Patients’ Online Ratings of

Their Physicians Over a 5-Year Period. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 14.

Geierhos, M., Bäumer, F.S., 2015. Erfahrungsberichte aus

zweiter Hand: Erkenntnisse über die Autorschaft von

Arztbewertungen in Online-Portalen. In: Book of

Abstracts der DHd-Tagung 2015, pp. 69–72, Graz.

Horton, J. & Golden, J., 2015. Reputation Inflation:

Evidence from an Online Labor Market. Working

Paper. New York University.

Huang, F., 2007. Building social trust: A human-capital

approach. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical

Economics, Mohr Siebeck, 163(4), 552-573.

International Organization for Migration. Migracija skaičiais

– EMN, http://123.emn.lt/en, Accessed 2019-02-19.

Jacobson, P., 2007. Empowering the physician-patient

relationship: The effect of the Internet. Partnership:

The Canadian Journal of Library and Information

Practice and Research, 2(1).

Jameda.de. jameda übernimmt mit Patientus deutschen

Marktführer für Videosprechstunde, Accessed 2019-02-

19. German: https://jameda.de/presse/pressemeldungen/

?meldung=165.

Jøsang, A.; Hayward, R. & Pope, S., 2006. Trust network

analysis with subjective logic. Proceedings of the 29th

Australasian Computer Science Conference, 48, 85-94 .

Lenert, L., 2010. Transforming healthcare through patient

empowerment Studies in Health Technology and

Informatics. IOS Press, 153, 159-175.

Lu, T.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y. & Zhang, C., 2016. Internet Usage,

Physician Performances and Patient’s Trust in

Physician During Diagnoses: Investigating Both Pre-

Use and Not-Use Internet Groups. 49th Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS,

Koloa, HI, USA, 3189-3198.

Lu, T.; Xu, Y. C. & Wallace, S., 2018. Internet usage and

patient’s trust in physician during diagnoses: A

knowledge power perspective. Journal of the

Association for Information Science and Technology,

69(1), 110-120.

Luca, M. & Zervas, G., 2016. Fake It Till You Make It:

Reputation, Competition, and Yelp Review Fraud.

Management Science, 62, 3412-3427.

Ma, X.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Jiang, Q. & Gao, S., 2018. ARMOR:

A trust-based privacy-preserving framework for

decentralized friend recommendation in online social

IoTBDS 2019 - 4th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

154

networks. Future Generation Computer Systems, 79, 82-

94.

McMullan, M., 2006. Patients using the Internet to obtain

health information: How this affects the patient–health

professional relationship. Patient Education and

Counseling, Elsevier BV, 63(1-2), 24-28.

Nützel, N., 2018. Angst vor Manipulation: Ärztin klagt

gegen Bewertungsportal Jameda - BGH verhandelt |

Nachrichten | BR.de, Accessed 2018-02-12.

Ridd, M.; Shaw, A.; Lewis, G. & Salisbury, C., 2009. The

patient-doctor relationship: a synthesis of the

qualitative literature on patients’ perspectives. British

Journal of General Practice, 59(561), e116-e133.

Sherchan, W.; Nepal, S. & Paris, C., 2013. A survey of trust in

social networks. ACM Computing Surveys, Association for

Computing Machinery (ACM), 45(4), 1-33.

Suki, N. M., 2011. Assessing patient satisfaction, trust,

commitment, loyalty and doctors’ reputation towards

doctor services. Pakistan Journal of Medical Science,

27(5), 1207-1210.

In Reviews We Trust: But Should We? Experiences with Physician Review Websites

155