IoT for Playful Intergenerational Learning about Cultural Heritage:

The LOCUS Approach

Ana Carla Amaro

a

and Lídia Oliveira

b

University of Aveiro, Campus de Santiago, Digimedia - Digital Media and Interaction Research Center,

Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: Intergenerational, Playful, Internet of Things, Cultural Heritage.

Abstract: LOCUS is a three-year multidisciplinary project with the goal of co-design, develop and evaluate an IoT

system and understand its potential to support playful intergenerational engagement in creating and exploring

cultural contents and learning about cultural heritage of rural territories from the Centre Region of Portugal,

namely Amiais village, in Sever do Vouga. By implementing a playful and immersive cultural heritage

tourism approach to foster Amiais' cultural and socioeconomic development, LOCUS will allow visitors to

have immersive gamified experiences, by using a wearable device (bracelet) and their smartphones to interact

with augmented everyday things around the village and to collaboratively learn about Amiais' culture and

produce and share multimedia georeferenced contents.

1 INTRODUCTION

Due to huge advancements in electronics and wireless

communication systems, mobile, pervasive and

ubiquitous devices and services have been providing

anytime-anywhere connectivity to the users,

interlinking physical and cyber world and leading to

the emergence of the Internet of Things (IoT), that has

been acting as a powerful innovation driver, coming

to revolutionize people and enterprises’ routines

(Borgia, 2014; Gonçalves, 2016; Park, et al., 2012;

Ray, 2018).

IoT refers to a highly dynamic and radically

distributed global infrastructure of networked

physical objects. Augmented by technology, these

objects became smart, gaining the ability to sense,

process and communicate on the network, being able

to interact with human users and other objects and to

trigger actions on the physical realm (Atzori, et al.,

2017; Borgia, 2014; Kortuem, et al., 2010; Miorandi,

et al., 2012).

Although research has been mainly focused on

IoT technical challenges, there is a growing interest

on how people can interact through it, in a

sociocultural and playful perspective (Darzentas, et

al., 2015; Wyeth et al., 2015).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7863-5813

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3278-0326

The LOCUS project is particularly interested in

how playful interactions with smart objects can be

designed to promote intergenerational

communication, as a mean to avoid isolation of rural

populations and contribute to healthy ageing,

countering ageism and preventing the waste of older

adults’ experience and knowledge, while preserving

the cultural heritage of rural territories.

Since older adults are often reluctant to use

information and communication technologies (ICT)

(FCT, 2013; Neves, et al., 2013), the IoT approach,

by allowing the augmentation of everyday objects and

routines (Brereton, et al., 2015), seems an adequate

solution.

In this way, LOCUS main goal is to co-design,

develop and evaluate an IoT system and understand

its potential to support playful intergenerational

engagement in creating and exploring cultural

contents and learning about cultural heritage of

Amiais village, in Sever do Vouga. Amiais is a rural

space, with an aging population, that preserves

ancient rural traditions, which are still practiced by

the few permanent inhabitants, as is the case of the

maintenance of communal threshing floors, an old

gathering point for the farming communities linked to

the husking of corn and the ritual of desfolhada,

282

Amaro, A. and Oliveira, L.

IoT for Playful Intergenerational Learning about Cultural Heritage: The LOCUS Approach.

DOI: 10.5220/0007747202820288

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2019), pages 282-288

ISBN: 978-989-758-368-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

which are still done today. Other traditions and rituals

remain alive, such as the midnight mass and singing

the janeiras, the slaughter of the pig and the

traditional rojoada after the slaughter.

The project also aims to propose an IoT model for

the promotion of rural territories in a playful and

immersive cultural heritage tourism approach. In this

approach, visitors will have immersive gamified

experiences, by using a wearable device (bracelet)

and their smartphones to interact with augmented

everyday things around the village and to

collaboratively learn about Amiais’ culture and

produce and share multimedia georeferenced

contents.

2 BACKGROUND

In an IoT-based system, smart objects became

pervasive and able to provide information and

services to users, through data sharing features,

standardized and interoperable communication

protocols and unique Internet addressing schemes

(Atzori, et al., 2010; Atzori et al., 2017; Miorandi et

al., 2012; Ray, 2018; Vermesan et al., 2011). These

objects may possess means to sense physical

phenomena, like temperature or light, thereby

providing information on the current context or

environment, or to trigger actions having an effect on

the physical realm (actuators) (Miorandi et al., 2012).

They are called smart objects because they show

intelligent behaviour when interacting with other

devices and operate autonomously over the internet

(Paul, et al., 2016), being able to create new services,

even without direct human intervention (Vermesan et

al., 2011).

Borgia (2014) describes the three phases of IoT

working way:

i) collection phase, referring to procedures for

identifying objects and sensing the physical

environment, most commonly through Radio-

Frequency Identification (RFID) and sensors;

ii) transmission phase, that includes mechanisms

to deliver the collected data to applications and to

different external servers, requiring methods for

accessing the network through gateways and

heterogeneous technologies (e.g., wireless, satellite),

for addressing and for routing; and, finally,

iii) process, management and utilization phase,

that deals with information flow, forwarding data to

applications and services, providing feedbacks to

control applications and being responsible for device

discovery and management, data filtering and

aggregation, semantic analysis, and information

utilization.

The IoT genesis is clearly utilitarian and it finds

applicability in many scenarios such as cities (e.g.

traffic control), homes (e.g. security systems), retail

(e.g. inventory optimization), etc. Considering the

“human” setting, specific IoT devices can attach to

human body to enable health and wellness

applications, like monitoring chronic disease or

exercise, and productivity-enhancing applications,

such as providing real time assistance in performing

complex tasks through devices like electronic glasses

and augmented reality technology (AIOTI, 2017;

Manyika et al., 2015).

In a more sociocultural and playful perspective,

there has been an increasing interest on how people

can connect and interact through IoT and what impact

it has on our lives (Darzentas et al., 2015; Girau, et

al., 2017; Wyeth et al., 2015). Schreiber et al. (2013)

suggests that IoT design should focus on interaction

and consider shared awareness, intimacy and

emotions, since objects’ smartness depends on how

people are able to interact with them.

On the other hand, play is a socially grounded and

cultivated activity, in which learning can be

undertaken without any repercussions (Huizinga,

1950), being an exploratory means for continuously

updating our interpretations of concepts, objects,

people and emotions and how these variables relate

(Arnab, 2017). By diminishing boundaries between

physical and digital spaces, IoT provide great

opportunities for the use of games in non-

entertainment contexts (Serious Games) (McGonigal,

2011), and of game design elements in non-game

contexts (Gamification) (Deterding, et al., 2011),

allowing for game-based informal learning

experiences in everyday contexts (Arnab, 2017), but

also for non-structured free play activities (Morrison,

et al., 2011) and even storytelling (Darzentas et al.,

2015).

Recently, some interesting projects and studies in

these domains have been developed. Ghost Hunter

(Banerjee and Horn, 2014) is an IoT interactive

system to engage parents and children in a game-

based activity for seeking out hidden sources of

energy consumption in their homes. Messaging Kettle

(Brereton et al., 2015) aims to foster social

connection with a distant elderly friend or relative, by

augmenting the routine of boiling the kettle to make

tea. The Storytellers Project (Boffi, 2017) is a library

remote reading aloud service connecting a

community of older adult readers, who borrow

children books and get an augmented bookmarker, to

children and their families, that borrows an

IoT for Playful Intergenerational Learning about Cultural Heritage: The LOCUS Approach

283

augmented storyteller doll: by playing with the doll,

the child requests a storytelling to the community of

storytellers, which will be notified through their

bookmarker, with a sound and light. The bookmarker

will also capture and transmit the readers voice, that

will be listen through the doll.

Some other projects and studies have been

exploring how augmented and traceable objects can

be enablers of memory, meaning and engaging

narratives, such as Tales of Things (Jode, et al., 2013)

and the study conducted by Darzentas et al. (2015)

about how Wargaming Miniatures acquire data

footprints.

Rural territories urge for cultural heritage

preservation, both tangible culture (such as

monuments, works of art, artefacts) and intangible

culture (such as folklore, traditions, knowledge) (Jara

et al., 2015). UNESCO (2017) states that protecting

our heritage and fostering creativity is crucial to

social identity and cohesion and to build open,

inclusive and pluralistic societies.

The understanding that heritage is actually

defined by ordinary people instead of heritage

organizations and places emphasizes that heritage

meanings and values emerge from dealing with

artefacts, places and practices in the lived world of

ordinary people, linking humans and nonhumans in

chains of connectivity (Giaccardi and Plate, 2017). It

is possible to list a very interesting set of projects that

demonstrate how IoT can bring those connections to

matter, in formal and informal cultural heritage

settings.

Moving People (Power of Art House, 2015) is a

guerrilla street art project in the context of which

10,010 3D refugees’ miniatures were placed around

Amsterdam public spaces, linking to a web page in

which their stories can be read. Tales of a Changing

Nation (Museum Diary, 2011) was an intervention at

National Museum of Scotland that augmented 80

objects from Scotland’s history with digital

information and also let visitors attach personal

memories do them. The EU project meSch (Petrelli et

al., 2016) provides an IoT platform for heritage

professionals to set up smart exhibitions, by enriching

objects with digital content that can be accessed

through augmented reality.

Research and Development in the role of IoT in

the preservation and promotion of the cultural

heritage of rural territories is globally reduced and

projects in Portugal are unknown. As such, LOCUS

presents itself as an innovative project, as it proposes

the co-design, development and evaluation of an IoT

system that incorporates and interconnects intelligent

and social objects, supporting tangible and playful

interactive experiences to promote the

intergenerational creation and exploration of

georeferenced cultural contents and learning about

the cultural heritage of rural territories.

3 METHODS

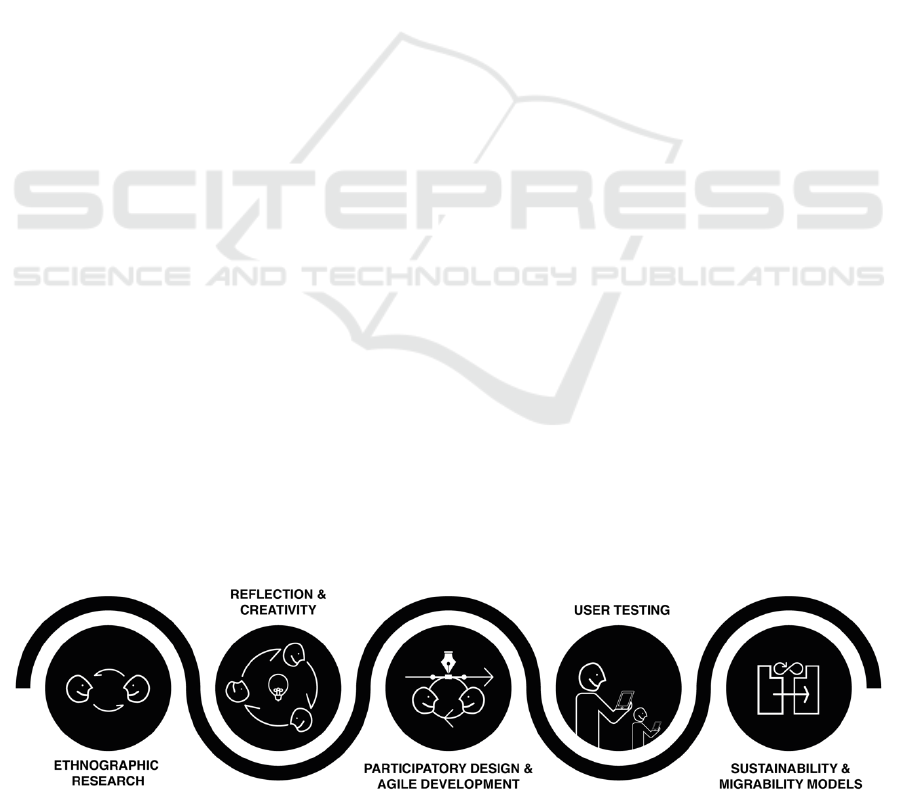

The development of the project will go through 5

fundamental stages, as shown in Figure 1.

In the first stage, the main goal is to develop a

holistic view and a comprehensive and descriptive

understanding of the culture and everyday life of

Amiais village and its inhabitants.

As such, and by employing an ethnographic

approach, two researchers will live in the village, in

order to:

i) uncover the culture, rituals, habits and stories of

Amiais and its inhabitants;

ii) get familiar with the motivations, wishes and

plans of the village’s inhabitants, visitors and

stakeholders;

iii) understand what people could find playful and

how they might establish playful interactions with

others and with objects;

iv) seek synergies with stakeholders (such as local

government entities, cultural and recreational

associations, schools).

Data will be collected mainly by using participant

observation, semi-structured interviews and focus

groups.

Figure 1: Stages of project development.

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

284

The following stage of the project will comprise

the content analysis of transcripts of interviews and

focus groups, and the hermeneutic and semiotic

analysis of field journals, containing the data

collected through participant observation, as well as

the interpretation, discussion and consolidation of all

the information gathered and knowledge acquired

during the period of ethnographic immersion.

Also, during this stage, creative sessions with the

inhabitants, stakeholders and visitors will be

promoted, in order to discuss and consolidate the

results of the analysis and to brainstorm and envision

scenarios and narratives for IoT playful

intergenerational experiences in Amiais village.

Based on these scenarios and narratives, the

needed IoT infrastructure testbed is going to be drawn

and the technical specifications for its

implementation (specific network coverage, required

amount of hardware and middleware, and so on) are

going to be identified. Along with those, the issues

concerning the technical implementation of the whole

IoT system are also going to be defined, including the

functional and technical requirements for the

wearable device (bracelet) and the mobile App

prototypes, as well as a technical feasibility study for

the identification of the most suitable technologies

and development platforms.

The stage three of the project development will

begin with the installation of the IoT infrastructure

testbed previously drafted and the development of the

prototypes of the bracelet and the App. In the

meanwhile, the design and development team will be

formed, namely through the selection of the

inhabitants, stakeholders and visitors to participate

and by ensuring a high degree and quality of their

participation in Participatory Design processes.

Participatory Design is about the direct

involvement of people in the co-design of ICT they

use and how design processes can be adjusted to

embrace that involvement (Simonsen and Robertson,

2012). As the degree and quality of this participation

depends on the technology potential awareness of

people involved, it will be necessary the design and

deliver of training sessions to foster this awareness,

thus ensuring that the inhabitants, stakeholders and

visitors have, in fact, a voice in the outcome.

Agile Development, on its turn, is an iterative

time-boxed methodology, involving design,

development and testing sprints or iterations, which

imply a continuous incremental improvement of what

is being developed, greatly reducing costs and time to

market (Cockton, et al., 2016; Meyer, 2014).

A strategy to bring together Participatory Design

and Agile Development methodologies will be

assembled and tested, and it must consider the need

to adapt the overly abstract representations of

traditional design and development tools and

processes, in order to facilitate participation, using,

for example, design games, cardboard mock-ups and

case-based prototypes (Simonsen and Robertson,

2012).

Sprints of design, development and testing (by the

target audience through direct observation methods)

will bring to life consecutive versions of the IoT

system, until a final prototype version is achieved.

Once a sufficiently robust version of the IoT

system prototype has been developed, it will be

possible to start the user testing phase, by carrying out

case studies with different user groups (children,

young people, seniors, intergenerational, foreigners,

etc.), for large-scale testing and evaluation of the

developed IoT system prototype. According to the

results of this phase, the architecture, functionalities,

interaction design, content, etc., of the IoT system

will be tuned.

The analysis of the data collected during these

studies will also allow:

i) to understand how the individual characteristics –

such as age, background, culture, digital literacy,

goals, roles, etc., - may impact the way people interact

in/with a playful social IoT system and how they

cooperate in creating and exploring cultural contents;

and,

ii) to develop an insight on how the physical and

technological characteristics of smart objects impact

playful and intergenerational interactions and

collaborative exploration and creation of cultural

content.

Based on the results of all the previous stages,

LOCUS final stage aims to ensure the sustainability

of the IoT system beyond the lifetime of the project.

The involvement and commitment of the stakeholders

will be fundamental to guarantee the sustainability of

the IoT system; thus, the strategies to do so - which

may include, for example, commercially exploiting

the system, integrating it into advertised national

tourist offers, etc. - should be jointly designed and

negotiated.

This last stage also comprises the development of

a model for the promotion of rural territories in a

playful and immersive cultural heritage tourism

approach that will make possible the migration of the

used methodology and of the developed IoT system,

to other rural territories that share cultural heritage

aspects with Amiais village.

The pursuit of this goal will depend on the prior

definition of the key elements to be integrated into the

model, which will certainly consist of different

IoT for Playful Intergenerational Learning about Cultural Heritage: The LOCUS Approach

285

interrelated layers, such as a methodological layer

(which may translate into guidelines, for example), a

technical layer (related with the infrastructure and all

the physical and logical dimensions of the IoT

system), an anthropological or ethnographic layer

(which will consider the particular elements of the

cultural heritage) and an intergenerational

communication layer (which will address the

characteristics of this communication and the

essential elements for its promotion).

4 EXPECTED RESULTS AND

MAIN OUTCOMES

As a springboard to accomplish LOCUS’ goals, a

network architecture of an IoT testbed will be

developed and installed in Amiais. Over this testbed,

several use cases will be implemented:

i) Environmental monitoring - IoT devices will

measure environmental parameters, such as light,

presence of vehicles or people;

ii) Location-based information – points of interest and

objects will be digitally tagged, according to playful

intergenerational co-designed scenarios/narratives.

When read by the users’ smartphones, those

tags/labels allow the distribution of georeferenced

information, namely through Augmented Reality;

iii) Playful interactions - a wearable device taking the

form of a bracelet with embedded sensors will be

developed, to recognize accelerations, movements

and rotations of the wearer’s hand. The bracelet will

communicate with an App, allowing that, based on

the object identification and the gestures performed

(shake, roll, etc.), the system may send specific

feedback (playing certain sounds, asking users to

perform additional actions, delivering Augmented

Reality contents…). For example, the husking of corn

traditions and rituals can be one of the

scenarios/narratives for an IoT immersive gamified

experience. Listening, learning about and producing

traditional music, such as the music linked to the

desfolhada or janeiras rituals, through

technologically augmented instruments, is another

IoT experience that can be foreseen;

iv) Participatory sensing and cultural content

production – users utilize their mobile phones to send

physical information (e.g. GPS coordinates) and to

produce and send multimedia cultural contents

(videos, sound or photos), which feed the IoT

platform and can be posteriorly accessed both through

the App and the online platform. Also, users can

subscribe to different services, such as getting alerts

for future new experiences occurring in the village.

Besides the IoT system, LOCUS will provide for

the realization of a diverse set of processes, actions,

contents, documents and technologies that will

materialize in three more main outcomes:

i) a set of guidelines that will translate the strategy

used to bring together Participatory Design and Agile

Development methodologies;

ii) a Sustainability model, referring to a set of

strategies to ensure the sustainability of the IoT

system beyond the lifetime of the project; and

iii) a Migrability model, to guide the migration of

LOCUS methodologies and IoT system to other

similar rural territories (Amiais assumes itself as a

prototypical village).

Additionally, the project will provide context for:

Cultural artistic productions and creations, such

as promotional multimedia and video materials to

disseminate the project, inspire people and raise

social awareness on the need to preserve the Cultural

Heritage of rural territories; Video documentaries on

Amiais’ everyday life and cultural heritage;

Multimedia and 3D contents (e.g., for Augmented

Reality) to integrate the IoT playful and

intergenerational experiences;

The edition of a book, which will aggregate the

most relevant contributions of the project for the

national and international scientific community;

The publication of research papers in peer-

reviewed international journals and prestigious

international scientific events proceedings, indexed in

the major scientific databases;

The organization of annual seminars, aimed at

postdoctoral, doctoral and master's students, peer

researchers and stakeholders, in which LOCUS’s

activities and results will be presented and discussed,

allowing a critical analysis and evaluation of the work

developed, as well as the integration of the knowledge

generated in higher education activities;

The development of pluri- and multidisciplinary

masters dissertations and doctoral thesis, enabling

students to develop skills and knowledge in LOCUS’

intervention areas and simultaneously facilitating the

project development and the achievement of the

project goals.

5 CONCLUSIONS

LOCUS implements a playful and immersive cultural

heritage tourism approach to foster social, cultural

and economic development of portuguese rural

territories, namely Amiais village, and promote

intergenerational communication, as a mean to avoid

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

286

isolation and contribute to healthy ageing. By

employing an ethnographically based and agile

participatory design methodology, LOCUS will

deliver an IoT system, which will enable Amiais’

visitors to have immersive gamified experiences,

collaboratively learn about the cultural heritage of the

village and produce and share multimedia

georeferenced contents.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project is co-funded by FCT - Foundation for

Science and Technology, through national funds, and

by the European Regional Development Fund,

framed in the Operational Programme for

Competitiveness and Internationalisation -

COMPETE 2020, under the new partnership

agreement PT2020.

REFERENCES

AIOTI., 2017. AIOTI - Alliance for Internet Of Things

Innovation. Retrieved April 13, 2017, from https://aioti-

space.org

Arnab, S., 2017. Playful and Gameful Learning in a Hybrid

Space. In C. V. de Carvalho, et al. (Eds.), Serious

Games, Interaction and Simulation. 6th International

Conference SGAMES: International Conference on

Serious Games, Interaction, and Simulation, Vol. 176,

pp. 9–14. Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-

51055-2Atzori

Atzori, L., et al., 2010. The Internet of Things: A survey.

Computer Networks, 54(15), pp. 2787–2805, Elsevier.

Atzori, L., et al., 2017. Understanding the Internet of

Things: definition, potentials, and societal role of a fast

evolving paradigm. Ad Hoc Networks, 56, pp. 122-140,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adhoc.2016.12.004

Banerjee, A., and Horn, M. S., 2014. Ghost hunter: parents

and children playing together to learn about energy

consumption. Proceedings of the 8th International

Conference on Tangible, Embedded and Embodied

Interaction, (c), pp. 267–274,

https://doi.org/10.1145/2540930.2540964

Boffi, L., 2017. The storytellers project. Retrieved April 14,

2017, from http://lauraboffi.com/THE-

STORYTELLERS-PROJECT

Borgia, E., 2014. The internet of things vision: Key

features, applications and open issues. Computer

Communications, 54, pp. 1–31.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2014.09.008

Brereton, M., et al., 2015. The Messaging Kettle:

Prototyping Connection over a Distance between Adult

Children and Older Parents. Proc. CHI 2015, pp. 713–

716. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702462

Bryman, A., 2012. Social Research Methods (4th ed.). New

York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Cockton, G., et al., 2016. Integrating User-Centred Design

in Agile Development. Human–Computer Interaction

Series. Springer International Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32165-3_1

Darzentas, D. P., et al., 2015. The Data Driven Lives of

Wargaming Miniatures. Chi 2015, pp. 2427–2436,

https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702377

Deterding, S., et al., 2011. Gamification: toward a

definition. In Chi 2011, pp. 12–15, https://doi.org/978-

1-4503-0268-5/11/0

Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, 2013. Vulnerable

People & ICT in Portugal: the practice of more than 15

years. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/vtb05g

Giaccardi, E., and Plate, L., 2017. How Memory Comes to

Matter From Social Media to the Internet of Things. In

L. Muntean, et al. (Eds.), Materializing Memory in Art

and Popular Culture, pp. 65–88. Routledge.

Girau, R., et al., 2017. Lysis: a platform for IoT distributed

applications over socially connected objects. IEEE

Internet of Things Journal, 4662(c), p.1,

https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2016.2616022

Gonçalves, A. R., 2016. Research of the Internet of Things

business models in Portugal. NOVA Information

Management School, Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

Huizinga, J., 1950. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-

Element in Culture. London, Boston, Henley:

Routledge And Kegan Paul,

https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568202009004005

Jara, A. J., et al., 2015. Internet of Things for Cultural

Heritage of Smart Cities and Smart Regions.

Proceedings - IEEE 29th International Conference on

Advanced Information Networking and Applications

Workshops, WAINA 2015, pp. 668–675,

https://doi.org/10.1109/WAINA.2015.169

Jode, M. De, et al., 2013. Tales of Things : interacting with

everyday objects in an NFC world. In Proceedings of

BCS HCI 2013, pp. 1–4. Retrieved from

http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/rd/pubs/conferences/intern

et_of_things_2013/Tales_of_Things.pdf

Kortuem, G., et al., 2010. Smart Objects as Building Blocks

for the Internet of Things. IEEE Computer Society, 10,

pp. 1089–7801, https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2009.143

Manyika, J., et al., 2015. The Internet of Things: Mapping

the value beyond the hype. McKinsey Global Institute.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05029-4_7

McGonigal, J., 2011. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make

Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New

York: The Penguin Press,

https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.10.1.03bro

Meyer, B., 2014. Agile! The Good, the Hype and the Ugly.

Computer, Vol. 11. Springer International Publishing

Switzerland,

https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2003.1204375

Miorandi, D., et al., 2012. Internet of things: Vision,

applications and research challenges. Ad Hoc Networks,

10(7), pp. 1497–1516,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adhoc.2012.02.016

IoT for Playful Intergenerational Learning about Cultural Heritage: The LOCUS Approach

287

Morrison, A., et al. (2011). Building Sensitising Terms to

Understand Free-play in Open-ended Interactive Art

Environments. Technology, pp. 2335–2344,

https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979285

Museum Diary., 2011. Tales of a Changing Nation.

Retrieved April 15, 2017, from

http://museumdiary.com/2011/04/11/tales-of-a-

changing-nation/

Neves, B., et al., 2013. Coming of (Old) Age in the Digital

Age: ICT Usage and Non-Usage Among Older Adults.

Sociological Research Online, 18(2), pp.1–12,

https://doi.org/doi:10.5153/sro.2998

Park, K. J., et al., 2012. Cyber-physical systems: Milestones

and research challenges. Computer Communications,

36(1), pp. 1–7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2012.09.006

Paul, A., et al., 2016. Smartbuddy: Defining Human

Behaviors Using Big Data Analytics In Social Internet

Of Things. IEEE Wireless Communications, 23(5), pp.

68–74. https://doi.org/10.1109/MWC.2016.7721744

Petrelli, D., et al., 2016. MESCH: Internet Of Things And

Cultural Heritage. SCIRES-IT-SCIentific RESearch and

Information Technology, 6(1), pp. 15–22. Retrieved

from http://caspur-ciberpublishing.it/index.php/scires-

it/article/viewFile/12005/11014

Power of Art House., 2015. Moving People. Retrieved from

https://www.movingpeople.nu

Ray, P. P., 2018. A survey on Internet of Things

architectures. Journal of King Saud University -

Computer and Information Sciences, 30(2), pp. 291–

319,

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2016.10.

003

Schreiber, D., et al., 2013. Introduction to the Special Issue

on Interaction with Smart Objects. ACM Transactions

on Interactive Intelligent Systems, 3(2), pp. 1–4,

https://doi.org/10.1145/2499474.2499475

Simonsen, J., and Robertson, T., 2012. Routledge

International Handbook of Participatory Design,

Routledge International Handbooks,

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108543.ch3

Vermesan, O., et al., 2011. Internet of Things Strategic

Research Roadmap. Retrieved from http://internet-of-

things-

research.eu/pdf/IoT_Cluster_Strategic_Research_Age

nda_2011.pdf

Wyeth, P., et al., 2015. The Internet of Playful Things. In

CHI PLAY 2015, p. 6. London; United Kingdom: ACM,

https://doi.org/10.5480/1536-5026-34.1.63

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

288