Deployment of MOOCs in Virtual Joint Academic Degree Programs

George Sammour

1a

, Abdallah Al-Zoubi

2

and Jeanne Schreurs

3

1

Department of Business Information Technology, Princess Sumaya University for Technology (PSUT), Amman, Jordan

2

Department of Communication Engineering, Princess Sumaya University for Technology (PSUT), Amman, Jordan

3

Department of Business Economics, Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium

Keywords: Online Learning, Massive Open Online Courses, MOOC, Adoption of MOOCs, Readiness of Students to

Take MOOCs.

Abstract: This research paper investigates the readiness of students to opt for MOOC courses in universities offering a

joint master degree international programme. A study is conducted on two joint academic study programs

offered by the University of Hasselt in Belgium and Princess Sumaya University for Technology in Jordan.

The study examines the readiness of students to take MOOC courses and their acceptance by universities’

management staff and professors. The study reveals promising results as the results suggest that such virtual

study programs are readily accepted in both universities by professors and students. On the other hand,

management staff and some professors expressed concerns on the approval of the equivalence of a MOOC

onto courses.

1 INTRODUCTION

International collaboration between universities has

become a necessity in order to gain access to

universal knowledge. Partnerships are key to staying

competitive with an up-to-date academic calendar

and be capable of satisfying larger numbers of

students and innovating quickly by developing

unique technologies on global scale. Specific

importance is given to join postgraduate degree

programs in order to enhance the international

visibility of higher education institutions, particularly

those taught in English (McCallum, 2010). However,

students’ mobility is a major obstacle in this type of

collaboration due to financial, social, political and

visa problems. In fact, many students find it difficult

to leave their jobs and families to join an international

university for long periods.

Since 2008, University of Hasselt (UHasselt) of

Belgium and Princess Sumaya University for

Technology (PSUT) of Jordan, have maintained

cooperation in a MSc Management with two

specialisations, namely management information

systems (MIS) and international marketing (IM).

According to the agreement, students take one

semester (four courses) at PSUT and then move to

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5080-8292

UHasselt for one academic year where they take extra

courses and complete a master thesis. Furthermore,

there is also a separate agreement for the exchange of

bachelor and master students and participation of

UHasselt students in a summer school at PSUT.

Massive open online course (MOOC) have been

found a suitable option for delivering learning content

online to students who opt to take a course instead of

physically move to the host university. Over the past

few years, several universities facilitated partnership

with MOOCs providers and are building MOOC

courses to serve as an e-learning versions of their

courses. In fact, providers on the internet are currently

making MOOCs available for learners who can study

the learning content on a self-paced manner and who

can complete readings and assessments and receive

help from a large community of learners through

discussion forums (Jasnani, 2013; Reilly, 2013).

Furthermore, MOOC providers attract students with

short, high quality instructional videos that

communicate learning content directly without

exceeding today’s student attention span thresholds

(Ong and Grigoryan, 2015). For example, in a typical

8- to 12-minute video, students would be provoked to

take two to three interactive quizzes to make sure they

understand the material before continuing with the

Sammour, G., Al-Zoubi, A. and Schreurs, J.

Deployment of MOOCs in Virtual Joint Academic Degree Programs.

DOI: 10.5220/0007754806370643

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), pages 637-643

ISBN: 978-989-758-372-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

637

lesson (Pappano, 2012). In addition, students can

interact, share, and critique ideas via blogs or

discussion board forums at a MOOC platform. They

can also meet fellow classmates from different

regions and work on joint projects, or support groups.

Although MOOCs have some common

characteristics with ordinary courses such as a

predefined schedule of sessions, assignments, and

assessments. However, access to MOOCs can be free

with no prerequisites other than internet access.

Furthermore, upon completion of the course, students

can have certification of completion which is

different from legal accreditation (Kope and Fournier,

2013). Krause and Lowe (2014) discuss a useful

composition of the claims made about the promises

and threats of MOOCs. They show that MOOCs have

the potential to challenge the closed nature of

academic knowledge in traditional universities. The

feature of openness of MOOCs is an essential

outcome of the Internet rather than a result.

Furthermore, there is high dropout rates for MOOC

courses and only few MOOC courses are available by

universities, which provides the pathways and

supports to recognise the academic qualifications. On

the other hand, the growth of the MOOC has potential

to address the problem of meeting increasing demand

for higher education.

Based on the above discussion, it has become

evident that MOOCs have become prominent in

education. In this paper, the case of collaboration

between UHasselt and PSUT in a master degree

programme is presented. The readiness of both

universities, staff and students to opt for MOOCs as

an optional mode of course delivery is discussed.

2 INTERNATIONAL

COLLABORATION IN

JOINT-DEGREE PROGRAMS

The collaboration between universities in the

international education field is mutually beneficial: it

gives the universities involved benefits and makes a

“win-win” situation possible by achieving more than

one could do in this field alone. It draws on the

experience and expertise available in different fields

and places and thus creates a better educational offer

on the international level that is also more

competitive. It thus achieves for the partners

worthwhile results that are more effective, better and

larger than when a university would do this on its own

alone. Success of the collaboration between

universities in the international education

automatically leads to an increased orientation

towards this collaboration program. One of the

important factors of success this program is indeed

the gaining of satisfaction of the students and their

families and the staff of both universities.

Since 2008, University of Hasselt (UHasselt) and

Princess Sumaya University for Technology (PSUT)

have maintained cooperation in an MSc Management

with two specialisations, namely Management

Information Systems (MIS) and International

Marketing (IMS). According to the agreement,

students take one semester (four courses) in PSUT

and then move to UHasselt for one academic year

where they take extra courses and complete a master

thesis. Furthermore, there is also a separate

agreement for the exchange of bachelor and master

students and participation of UHasselt students in a

summer school at PSUT.

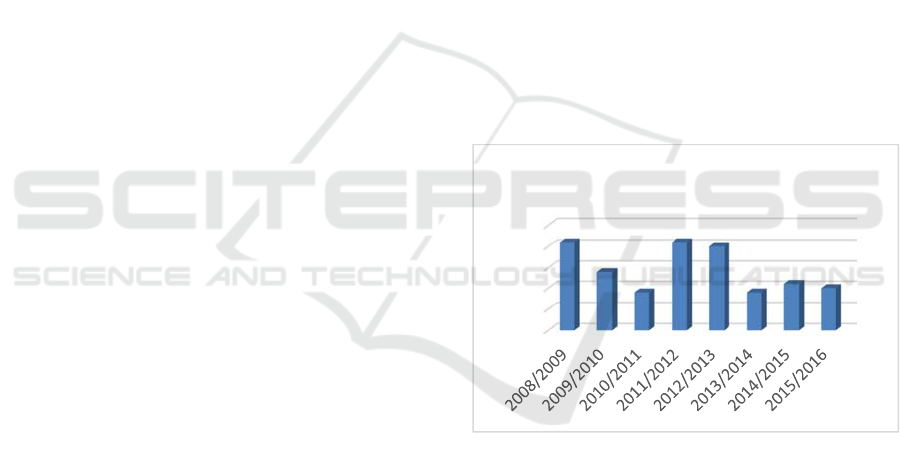

Figure 1 shows the number of Jordanian students

already studies at UHasselt. In addition, in the

academic years 2008 and 2009 UHasselt offered two

Ph.D. scholarships to PSUT. Two candidates already

earned their PhDs from UHasselt and now working as

professors at PSUT.

Figure 1: Number of Jordanian students enrolled in virtual

study programs at UHasselt.

PSUT utilizes an e-learning platform containing

all e-material, in the context of developing its solution

to develop e-learning and facilitate its

implementation. PSUT signed a Memorandum of

Understanding (MoU) with Doseyeh for e-learning

portals. The company provides contemporary

technologies in the e-learning through a social

academic network. Through these services, students

and professors can exploit the opportunity for e-

learning and exchange of information and courses

materials. These services will mitigate the load of

carrying heavy books and hard copies and save the

expenses of buying them. Through these services,

students will access and benefit from a number of

0

5

10

15

20

25

No.ofStudents

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

638

academic books and research services as well as be

able to upload their research online, obtain high

quality educational material and gain access to recent

publications. Through this agreement, PSUT can

make these services available to its international

partner's network to develop the e-learning platform

and databases.

UHasselt uses Blackboard, e-learning platform to

improve students’ skills, update their materials and

make a constantly contact with their teachers.

3 MOOCs AND OPEN

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

The term “Massive” in MOOCs stands for enrolling

thousands of students. The courses are “Open”

because anyone with an internet connection can enrol

and should not possess any prerequisites such as a

qualification or a level of performance in earlier

studies. The access is free except if a learner opts for

a certificate or an academic credit. MOOCs are

inherently online and are considered as “courses"

because they are scheduled in a timeframe, have

assignments, tests and exams to assess the knowledge

gained by students. After finishing the learning

process, students can obtain a certificate, being

sometimes accepted as a college credit.

Despite the success of MOOCs in enrolling

massive numbers of students, only a very limited

number of registered learners are completing the

course, and the majority stops learning already at an

early stage. As an example, the University of

Edinburgh recorded that only 12% of the enrolled

students completed the course (Rosewell and Jansen,

2014). The average MOOC course is found to enrol

around 43,000 students, 6.5% of whom complete the

course. Enrolment numbers are decreasing over time

and are positively correlated with course length.

Completion rates are consistent across time,

university rank and total enrolment, but negatively

correlated with course length.

Low completion rates might indicate that the open

nature of MOOCs allows students to enrol on courses

for which they are ill prepared. However, many

MOOC participants appear well qualified if not over-

qualified. For example, in San Jose State University,

a pilot project to deliver for-credit MOOCs using

Udacity, was carried out with a target audience of

students who are presently under-served and left out

of higher education and the courses were pitched at

college entry level. However, 53% of the student

body had post-secondary qualifications, including

20% with Masters or PhD (Ferenstein, 2013).

Apparently, there are several reasons for the low

completion rate. First, students are not able to find the

best information they need to choose the right course

at the right level. Consequently, they fail to match

their level of knowledge. In addition, students miss

the relevant content required in their learning process.

Second, students are not motivated for individual

self-paced learning due to tiresome and ineffective

learning model and characteristics of an individual

study environment. Third, students lack the practical

sense to pass exams because universities and

employers do not accept certificates of MOOC

courses. Therefore, students are not motivated to take

exams.

Therefore, to address the abovementioned

MOOCs issues, a research experiment was conducted

by adopting MOOCs in a joint master degree program

offered by University of Hasselt and Princess Sumaya

University for Technology (PSUT). The courses

chosen were those which are pre-requisites taken at

PSUT as students will have to take post-requisites at

UHasselt. Furthermore, students report the adoption

of MOOCs, faculty and management at both

universities provided feedback by means of survey.

The results were analysed in regards to the degree of

personalization and knowledge sharing.

3.1 Acceptance of MOOCs by

Universities and Students

Current statistics reveal that the completion rate of

MOOCs is very low. Only about 15% of the enrolled

students become certified while the vast majority stop

learning at an early stage (Jordan, 2015; Zhenghao et

al., 2015). According to a study conducted by Chuang

and Ho (2016), in the first four years of the edX

MOOC platform there were 4.5 million participants

and 245 thousand obtained a certificate. This implies

that only 5.5% obtained credentials for taking the

online course. Furthermore, one report shows that

completion rates are generally between 2 and 13

percent of enrolled students (Perna et al., 2014); other

reports suggest an average completion rate of 10%

(The Economist 2014). According to Perna et al.

(2014), a review of 16 MOOCs used in the Coursera

platform by the University of Pennsylvania, reported

that the completion rate (participants receiving a final

grade of at least 80%) was 4%. On the other hand,

DeBoer et al. (2014) argue that it is inappropriate to

calculate MOOCs completion rate based on

registration. Koller et al. (2013) suggested that taking

Deployment of MOOCs in Virtual Joint Academic Degree Programs

639

in consideration student intent is vital in assessing

course completion rate.

On the other hand, survey was conducted at the

start of the University of Derby’s Dementia MOOC,

where 775 learners were asked whether they expected

to fully engage with the course. More than 61% of

learners said yes, but 33% of learners stated that they

did “NOT INTEND TO COMPLETE” the course

(Clark, 2016). This showed that people come to

MOOCs with different intentions. The survey also

showed that around 35% of both groups completed

the course, which is a much higher level of

completion that the vast majority of MOOCs.

It seems that the problem of completion rate may

be identified due to two main reasons, first the

inability of students to match their level of knowledge

and complexity of choosing the right course at the

right level and covering the relevant content. Second

the lack of practical sense to pass exams because

universities and employers do not accept certificates

of MOOC courses.

A consortium of Big Ten universities, prepared a

briefing in late 2012 (Voss, 2013) about the MOOC

phenomenon for their provosts and presidents, posing

the question: Is this time different? That question was

based on the premise that, over the past decade, online

education has moved ahead relatively slowly with fits

and starts such that the disruption that is changing

higher education institutions and pedagogy has been

more evolutionary than revolutionary. The

consortium concluded that, indeed, the answer to the

question is a definite YES! To quote their view: “The

effect on residential universities relative to previous

experiences and events in the arena will be profound

and long-term.”

Accordingly, only time will tell if such predictions

are correct. Right now, for nearly all involved,

MOOCs are still an experiment. The institutions

involved thus far are prestigious, the faculty

renowned and motivated, and the topics largely

handpicked by the institutions, MOOC entities, or

both in concert. The participating colleges and

universities have stated that they believe their

involvement with these initial efforts will extend,

enhance, and preserve their institutional reach, brand,

and reputation.

3.2 Research Methodology

In order to investigate the readiness of students to take

MOOC courses and their acceptance by universities,

UHasselt and PSUT are organizing a student

exchange program. In a bilateral agreement, a set of

courses have been identified as equivalent courses

that can be exchanged between their corresponding

curricula. UHasselt is also organizing an international

master of Management Information Systems degree

program. A group of PSUT students participate in this

program annually to earn a master degree in MIS.

Nevertheless, some students may not participate in an

exchange program or international master's degree

program because they cannot stay abroad for a year

or a semester. Therefore, to overcome this concern a

solution to take virtual courses or to take part in a

virtual study program was proposed. Two types of

virtual study programs are set forward: a “virtual

international study program” and a “virtual exchange

study program”. In a virtual international study

program, a student is registered as an international

student in an international study program and can

replace some of the courses by MOOCs that are taken

in other universities. In a virtual exchange study

program, a student can add some MOOCs to his/her

selection of exchange courses of the exchange

program of his university.

To measure the feasibility and acceptance of both

educational models, success indicators were

identified. The success indicators are related to the

readiness of students to take MOOC courses and the

acceptance of MOOC courses by the universities.

Success indicators include, Quality of the online

learning process, required content coverage, courses

and topics selection, readiness for e-learning,

evaluation and assessment schemes, and international

cooperation and image.

A survey was organized using

questionnaires sent to management, professors, and

students of both universities. Furthermore, the

following research questions are set forward.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of

learning MOOC courses?

Are MOOC courses known, popular and already

taken by international students?

Are management and professors of University of

Hasselt prepared to organise a virtual international

study program, welcoming MOOC courses as part

of the curriculum and accept MOOC credits?

Are management and professors of PSUT and of

University of Hasselt willing to extend their

student exchange program to a virtual student

exchange program, accepting MOOCs courses as

part of the set of exchange courses, accepted in the

frame of the Erasmus program or by bilateral

agreements?

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

640

4 VIRTUAL STUDY PROGRAMS

BASED ON MOOCs AT

UNIVERSITIES

Currently, some research has systematically

examined student perceived advantages or limitations

associated with MOOC formats. However, students

post in the actual MOOC course shell is analysed,

which focuses on learning-centred aspect of students

towards MOOC (Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, such an approach only provides insight

into actively engaged MOOC students and fails to

account for students who engage the course content

but do not interact. Bremer (2012) suggest that,

MOOCs appeal most to very organized and self-

motivated students. As a result, the readiness of

students towards MOOCs can be measured by the

following success factors:

Availability of a good e-learning system.

Readiness for taking e-learning courses.

New kind of online evaluation and assessment

schemas.

Changed living situation and changed cost

structure

Two surveys were prepared to study the readiness of

students to take MOOC courses and the acceptance of

MOOC courses by the universities in the context of

two virtual study programs. The first is the virtual

international study program where students are

registered to pursue a master degree in MIS. In this

study program, students can replace some of the

courses by MOOCs at PSUT that are equivalent to

courses at the University of Hasselt. The second is the

virtual exchange study program, where students add

some MOOCs to their selection of exchange courses

of the exchange program of their university.

The survey related to the virtual exchange study

program is designed and directed towards

management personnel, professors and students at

both universities. The management personnel

questions include the legality of conducting such

study program, international image value added,

international cooperation, and quality of courses. The

questions related to the faculty were categorized to

the free selection from a global list (in context of

partnership agreement), covering required content,

quality of the online learning process (quality

influences the decision of equivalence). Finally, the

questions posed to students are related to the

e-learning system, the readiness for e-learning,

evaluation and assessment schemes and living and

cost conditions. The number of respondents to this

survey is 107 distributed as shown in Table 1. On the

other hand, the survey of the virtual international

study program is targeted to management personnel

and professors at UHasselt and to students from

PSUT pursuing an exchange experience at UHasselt.

The questions targeted to management personnel and

professors are related to the inclusion of virtual

students, online courses at UHasselt, possibility that

courses replaced by MOOCs, and student cannot

select a course by himself. Moreover, questions

targeted to students are associated to the e-learning

system, the readiness for e-learning, evaluation and

assessment schemes and the thesis work were

surveyed. The number of respondents to this survey

is 55 distributed as shown in Table 1. The surveys’

results reveal a high degree of acceptance and

readiness to the virtual exchange study program from

management personnel, professors and students’

perspectives in both universities. However, despite

the fact that 84.2% of professors at both universities

agree that the required topics are covered by the

MOOCS, one can notice that professors at both

universities (63.2%) are in favour of setting a pre-

specified course list for students. The results related

to the virtual international study program also reveal

that management, professors and students responded

in favour of the adaptation of MOOC courses.

Nevertheless, the thesis work conducted by students

needs some extra effort and organization as 45.7%

obviously have some concerns related to this topic.

The results of the surveys related to both programs

show a high degree of acceptance and readiness to

implement MOOCs in the context of international and

exchange study programs. However, professors and

students in both study programs raise some concerns

and issues related to courses selection and content.

Furthermore, management staff and professors raised

concerns related to the approval of the equivalence, in

terms of number of credit hours and content, of a

MOOC onto courses. UH adapts the ECTS (European

Credit Transfer System) while PSUT uses the credit

system. Therefore, management staff and professors

expressed concerns about the amount of time students

spend to complete the required course work and the

amount of knowledge gained. To overcome such

concerns, we proposed the flipped classroom

methodology to be applied in the joint study

programs. The flipped classroom approach is a

pedagogical model in which the typical lecture and

homework elements of a course are reversed. Thus,

students can first learn the basic concepts of a specific

course at home, using a range of pedagogical content

such as, videos, presentations, basic exercises, case

studies …etc. (Lage et al., 2000).

Deployment of MOOCs in Virtual Joint Academic Degree Programs

641

Table 1: Results of the study of the readiness of students to take MOOC courses and the acceptance of MOOC courses by

UHasselt and PSUT.

Virtual Exchange Study Program

Management: UH + PSUT

(5 respondents)

Criteria Response %

Legally possible: Yes: 20% Yes But: 80% No: 0%

International image: Yes: 60% Yes But: 40% No: 0%

International cooperation: Yes: 20% Yes But: 80% No: 0%

Free selection from a global list: Yes: 20% Yes But 60% No: 20%

Quality of course: Yes: 100% Yes But: 0% No: 0%

Professors: UH + PSUT

(19 respondents)

Criteria Response %

Free selection from a global list (in context of

partnership agreement):

Yes: 36.8% No: 63.2%

Covering required content:

Knowledge in the same domain: 15.8%

Covering most of the topics: 58%

All required topics covered: 26.2%

Quality of the online learning process (Quality

influences the decision of equivalence):

Yes: 84.2% No: 15.8%

Students: UH + PSUT

(83 respondents: UH: 36 and

PSUT: 47 students)

Criteria Response %

E-learning system: Yes: 79.5% Yes But: 13% No: 7.5%

Readiness for e-learning: Yes: 78% Yes But: 8% No: 14%

Evaluation and assessment schemes: Yes: 72.8% Yes But: 12% No: 15.2%

living and cost conditions: Yes: 65% Yes But: 12% No: 23%

Virtual international study program

Management and professors at

UH - master of MIS

(8 respondents)

Criteria Response %

Inclusion of virtual students: Yes: 48.5% Yes But: 39% No: 12.5%

UH online courses: Yes: 52.3% Yes But: 20% No: 27.7%

UH courses replaced by MOOCs: Yes: 37.5% Yes But: 62.5% No: 0%

Student cannot select a course himself Yes: 78% Yes But: 10% No: 18%

Students UH + potential

candidates students at PSUT

(55 respondents)

Criteria Response %

E-learning system: Yes: 76.5% Yes But: 13% No:10.5%

Readiness for e-learning: Yes: 75% Yes But: 10% No: 15%

Evaluation and assessment schemes: Yes: 70.8% Yes But: 12% No: 17.2%

Thesis work: Yes: 42.3% Yes But: 12% No: 45.7%

The flipped classroom methodology has been

applied in the two virtual study programs such that

UH professors designed content which students must

complete at home before coming to class. The

contents include a set of educational videos and

exercises available for students for an entire month

prior to the classroom session at their home

university. During the face the face lessons, more

complex activities than the exercises of the online

ones, which included solving problems and questions

related to the content presented by the videos in the

online phase. On the other hand, students were

allowed to ask questions related to the content

presented in the online phase.

The assessment process was performed by means

of paper exams, which are sent to UH professors to

correct and a percentage of the grade is dedicated to

the course work and the amount of time students

interact during the online phase.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The adoption of MOOCs by students and

management of two partner universities, PSUT in

Jordan and University of Hasselt in Belgium, in study

programs are promising as they suggest that virtual

study programs are accepted in both Universities.

However, professors in both universities elucidate

concerns on accepting the equivalence of the MOOC

courses to their own courses.

The results reveal that the realization of the virtual

exchange study program can be further tested. A few

equivalent MOOC courses have to be identified and

scheduled as part of a test-curriculum, organized in

parallel with the regular curriculum. The curriculum

council has to evaluate the courses and decide on the

number of credits that can be earned. Students

included in the test will evaluate their experience at

the end of the academic year resulting in improved

conclusions about the adoption of the MOOCs in the

university.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

642

REFERENCES

Beng Soo Ong and Ani Grigoryan (2015). MOOCs and

Universities: Competitors or Partners? International

Journal of Information and Education Technology,

Vol. 5, No. 5.

Bremer, C. (2012). New format for online courses: The

open course future of learning. Proceedings of

eLearning Baltics eLBa 2012.

Brian D. Voss (2013), “Massive Open Online Courses

(MOOCs): A Primer for University and College Board

Members.” An AGB white paper.

Christiane Reilly (2013). MOOCs Deconstructed:

Variables that Affect MOOC Success.

DeBoer, J., Ho, A. D., Stump, G. S., & Breslow, L., (2014).

Changing “course”: reconceptualizing educational

variables for massive open online courses. Educational

Researcher, 43, 74–84. Donald Clark: MOOCs: Course

Completion is the Wrong Measure of Course Success

(April 11, 2016). Retrieved from: https://www.class-

central.com/report/moocs-course-completion-wrong-

measure/ (accessed 14 September 2016).

Chuang, Isaac and Ho, Andrew, HarvardX and MITx: Four

Years of Open Online Courses -- Fall 2012-Summer

2016 (December 23, 2016). Retrieved from

SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2889436or http://dx.

doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2889436 (accessed 12 November

2018).

Ferenstein, G. (July 19, 2013). San Jose State’s bold

experiment in online ed disappoints, suspends, pilot

with Udacity. TechCrunch. Retrieved from

https://techcrunch.com/2013/07/19/san-jose-states-

bold-experiment-in-online-ed-disappoints-suspends-

pilot-with-udacity/

Jordan, K. (2015), “MOOC Completion Rates: The Data”,

Katy Jordan website, www.katyjordan.com/

MOOCproject.html (accessed 12 July 2018).

Koller, D., Ng, A., Do, C., & Chen, Z. (2013). Retention

and intention in massive open online courses: In depth.

Educause Review. Retrieved from: http://

www.educause.edu/ero/article/retention-and-intention-

massive-open-onlinecourses-depth-0

Krause, S. D., & Lowe, C. (Eds.). (2014). Invasion of the

MOOCs: The promises and perils of massive open

online courses. © 2014 by Parlor Press. Available at

http://www.parlorpress.com/pdf/invasion_of_the_moo

cs.pdf.

Lage, M. J., Platt, G. J. and Treglia, M., (2000). Inverting

the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive

learning environment, NJ Econ Educ 31, 30–43.

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Adams, A. A. and Williams, S.

A. (2013) MOOCs: a systematic study of the published

literature 2008-2012. International Review of Research

in Open and Distance Learning, 14 (3). pp. 202-227.

ISSN 1492-3831 Available at http://centaur.

reading.ac.uk/33109/.

McCallum Beatty, K. (2010). Selected Experiences of

International Students Enrolled in English Taught

Programs at German Universities. (Electronic Thesis or

Dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/

Pappano, L. “The year of the MOOC,” The New York

Times, November 4, 2012.

Perna, L. W., Ruby, A., Boruch, R. F., Wang, N., Scull, J.,

Ahmad, S. et al., (2014). Moving through MOOCs:

understanding the progression of users in massive open

online courses. Educational Researcher, 43, 421–432.

Preeti, Jasnani (2013): “Designing MOOCs”, A White

Paper on Instructional Design for MOOCs. Publisher:

Tata Interactive Systems.

Rita Kope, Helene Fournier (2013), “Social and Affective

Presence to Achieve Quality Learning in MOOCs”, in

Proceedings ELEARN conference, Oct 21, 2013 in Las

Vegas, NV, USA ISBN 978-1-939797-05-6 Publisher:

Association for the Advancement of Computing in

Education (AACE), Chesapeake, VA.

Rosewell, J. and Jansen, D., (2014), “The OpenupEd

quality label: Benchmarks for MOOCs” in The

International Journal for innovation and quality in

learning, Vol 2. No 3, pp 89-100.

The Economist, 2014. The digital degree. Available from:

www.economist.com/news/briefing/21605899-staid-

higher-education-business-about-experience-welcome-

earthquake-digital.

Chen Zhenghao, Brandon Alcorn, Gayle Christensen,

Nicholas Eriksson, Daphne Koller, Ezekiel J. Emanuel.,

(2015), “Who’s benefiting from MOOCs, and why”,

Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2015/09/

whos-benefiting-from-moocs-and-why# (accessed 30

September 2016).

Deployment of MOOCs in Virtual Joint Academic Degree Programs

643