Template-Driven Documentation for Enterprise Recruitment Best

Practices

Saleh Alamro, Huseyin Dogan, Raian Ali and Keith Phalp

Faculty of Science and Technology, Bournemouth University, U.K.

Keywords: Recruitment, Enterprise Recruitment, Enterprise Recruitment Best Practices, Enterprise Recruitment

Architecture.

Abstract: Recruitment Best Practices (RBPs) are useful when building complex Enterprise Recruitment Architectures

(ERAs). However, they have some limitations that reduce their reusability. A key limitation is the lack of

capturing and documenting recruitment problems and their solutions from an enterprise perspective. To

address this gap, a template for Enterprise Recruitment Best Practice (ERBP) documentation is defined. This

template provides a model-driven environment and incorporates all elements that must be considered for a

better documentation, sharing and reuse of ERBPs. For this purpose, we develop a precise metamodel and

five UML diagrams to describe the template of the ERBPs. This template will facilitate the identification and

selection of ERBPs and provide enterprise recruitment stakeholders with the guidelines of how to share and

reuse them. The template is produced using design science method and a detailed analysis of three case

studies. The evaluation results demonstrated that the template can contribute to a better documentation of

ERBPs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recruitment is the practice of attracting sufficient

numbers of qualified individuals on a timely basis to

fill job vacancies within an organization (Ahamed

and Adams, 2010). It is a key strategic opportunity for

organisations to achieve a competitive advantage

over rivals (Carless and Wintle, 2007). With this

purpose in mind, organisations should seek support

from enterprise architectures, shortly EAs (Penaranda

et al., 2010; Vallejo al., 2012).

EAs rely on the integration of both a conceptual

representation and a systematic approach to build a

system (Zachman, 2008). In enterprise recruitment

architectures (ERAs), the conceptual representation

facilitates communication and coordination within

and across the enterprise entities through a better

visualisation and understanding of the enterprise

components from different perspectives. On the other

hand, a step-by-step methodology is to systematically

transform the enterprise facilitated by different

principles, methods, and tools (Gartner, 2008).

Methodologies based best practices can provide a

systematic approach when building new information

system or evolving existing ones (Molina and

Medina, 2003). Recruitment Best Practices (RBPs)

are already being shared and reused to some extent in

some organisations (Madia, 2011). However, they

have some limitations that reduce their reusability: (1)

they are fragmented and limited in scope (Simard and

Rice, 2007; Buschmann et al., 2007); and (2) they

lack proper documentation (Vesely, 2011).

With these limitations and the need of ERAs

support, we define a template for Enterprise

Recruitment Best Practice (ERBP) documentation.

The objective of ERBP template is to provide a top-

down strategy based on models for defining ERAs in

different levels of abstraction towards software

specifications. An ERBP will identify and combine a

set of existing RBPs describing an ERA that fills a job

vacancy in a specific enterprise context. To do this,

we develop a precise metamodel complemented with

five UML diagrams to describe the template of the

ERBPs.

The goal of this paper is to design and evaluate a

template for supporting the documentation and reuse

of ERBPs. The main focus is on the template

proposed to define and document the elements of

ERBPs while the methodology of reusing ERBPs is

out of the scope of this paper. The paper is structured

as follows: this section presents an introduction to the

research study. Section 2 provides a brief review of

research on BPs sharing and reuse. Section 3 presents

the research methodology followed to design and

evaluate the ERBP template. Section 4 defines the

238

Alamro, S., Dogan, H., Ali, R. and Phalp, K.

Template-Driven Documentation for Enterprise Recruitment Best Practices.

DOI: 10.5220/0007766602380248

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), pages 238-248

ISBN: 978-989-758-372-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

ERBP template and the relationship with the ERA

elements. Section 5 shows the evaluation results of

the ERBP template. Finally, Section 6 presents some

conclusions and future work.

2 BEST PRACTICES

According to Renzl et al. (2006), best practices (BPs)

are key approaches for sharing and reusing explicit

knowledge. A great deal of research on the definition

of BPs and their impact on knowledge transfer and

reuse has been conducted. In the next subsections, the

definition of BPs and the challenges that impede the

sharing and reuse of BPs in general and recruitment-

related BPs in specific are presented.

2.1 Definition of BP

BP is related to different domains and contexts, and

is therefore subject to a variety of circumstantial

definitions. Graupner et al. (2009) define BP as the

most efficient and effective way of accomplishing a

task, based on repeatable procedures that have proven

themselves over time for large numbers of people.

Investopedia (2016) defines BP as a set of guidelines

or ideas that represent the most efficient and prudent

course of actions.

2.2 Challenges in Documenting BPs

One of the key challenges in sharing and reusing BPs

is the lack of proper documentation of BPs. More

precisely, incomplete description of BPs reduce their

reusability. Regardless of the industry of BPs, some

key examples of such incomplete description are: lack

of description of the purpose of the BPs (Hanafizadeh

et al. 2009); and lack of description of the problem

domain in which BPs are ‘best’ (Alwazae, 2015).

Complete description of BPs is very crucial in their

successful application and reusing (Mansar and

Reijers, 2007; Simard and Rice, 2007).

Given the complexity of real-world practices, one

way to promote BP completeness is to model the

various attributes of a BP and establish a consistent

structure for documentation (Vesely, 2011). This will

enable a proper documentation, sharing and reuse of

BPs. However, the way how a BP is properly

modelled and structured has not been examined

extensively in the literature (Alwazae, 2015). Hence,

it is a knowledge gap for which this paper attempts to

fill by providing a new template-driven

documentation of recruitment-related BPs.

2.3 Challenges in the Scope of BPs

BPs have been criticised being limited in scope

(Simard and Rice, 2007; Madia, 2011). This implies

being intended to piecemeal and fragmented

problems, and being seen as building blocks with no

means to be combined in one meaningful entity

(Stephenson and Bandara, 2007). Given that the focus

of this paper is on enterprise recruitment, this scope

will require new ways to capture and document

enterprise recruitment best practices (ERBPs). This

points up a knowledge gap in research for which the

paper will try to address.

2.4 Challenges in the Selection of BPs

These concern the difficulties in finding and selecting

BPs in large collections, or repositories (Hanafizadeh

et al. 2009; Vesely, 2011). In this paper, the focus will

be on providing domain-independent recruitment

concepts that serve as search indices (Vesely, 2011;

Graupner et al. 2009). These indices consists of

recruitment terms that are not associated with a

specific domain. Hence, practitioners are able to find

and select ERBPs from different domains and

industries.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The research method used is design science.

According to (Johannesson and Perjons, 2014),

design science creates new artefacts for solving

practical problems. These artefacts can be methods,

models, constructs, frameworks, prototypes or IT

systems, which are “introduced into the world to

make it different, to make it better” (Johannesson and

Perjons, 2014). The design science research process

carried out in this research included five research

activities as defined by the design science method

framework of (Johannesson and Perjons, 2014).

These activities and their application are presented

below.

3.1 Problem Explication

The first activity in the design science process is to

explicate the practical problem(s) that motivates why

the artefact(s), in our case the ERBP template needs

to be designed and developed. The practical problems

are: (1) RBPs are fragmented and limited in scope;

and (2) RBPs lack proper documentation. These

practical problems denote knowledge gaps in the

Template-Driven Documentation for Enterprise Recruitment Best Practices

239

literature which, in turn, impede sharing and reuse of

RBPs. These knowledge gaps have been discussed in

Section 2. Hence, the artefact (ERBP template) is

designed to solve these problems and fill these gaps.

3.2 Requirements Definition

The second activity in the design science process is to

define the requirements of the ERBP template. These

requirements will be used as a basis to evaluate the

resulting artefact and guide the construction process

of it in addition to any refinement steps. Based on the

literature review, the following requirements are

selected:

Requirement 1: The ERBP template shall be

comprehensive. The ERBP template shall

consist of a complete set of ERBP elements to

achieve its defined goal. According to the

research literature, the successful application of

BPs depends on their complete documentation

(Vesely, 2011).

Requirement 2: The ERBP template shall be

easy to use for sharing and reusing. Users should

be able to use the artefact to achieve a particular

goal easily. According to the research literature,

a clear documentation structure will distil

information about a BP and makes it easy to use

(Motahari-Nezhad et al. 2010).

Requirement 3: The ERBP template support both

the creation of high quality ERBPs and the

evaluation of already existing ERBPs. This

means that the ERBP template should enable

documenting of new ERBPs as well as guide the

quality assessment of already designed ERBPs.

According to research literature, a well-structured

BP template will facilitate the creation and

evaluation of BPs (Jashapara, 2011).

3.3 Design and Development

This third activity is to design and develop the artefact

that address the explicated problems and fulfils the

defined requirements, in this case design and develop

the ERBP template.

The ERBP template was developed by means of

two complementary processes: (1) addressing the

elements of ERAs that support ERBP documentation;

and (2) addressing the elements of ERBP template for

documentation. The results of these two processes

were merged together into the final ERBP template.

The ERA elements were selected from the

artefacts (POCM and Onto-RPD) designed from the

analysis of three case studies (SA enlistment, BA

enlistment (UCAS recruitment) conducted in Alamro

et al. (2018). The links between ERA elements were

also addressed. Thanks for the POCM and Onto-RPD

artefacts. However, the elements of ERBP template

were selected from the template provided by

Buschmann et al. (2007) with some important

elements added from the literature.

The elements of ERA and ERBP template were

combined together in fulfilling of the defined

requirements. The tentative draft of combination was

validated and refined in a number of refinement

phases. In each of which, one or two academic experts

were asked to evaluate and refine the ERBP template.

Purposive sampling was applied. In total, six

academic experts in the area of BPs were interviewed.

The final ERBP template is described in Section 4.

3.4 Demonstration and Evaluation

This activity is to use and assess how well the artefact

solves the practical problem based on the defined

requirements. We have evaluated the ERBP template

by conducting a focus group of recruitment-related

academic experts. The number of participants was 10

and the results are presented in Section 5.

4 ERBP TEMPLATE

The ERBP template is designed to document the key

elements of recruitment practice in an enterprise

environment. These elements are a combination of

ERA elements and the elements of a selected template

from the literature for a more comprehensive

documentation of an ERBP. The ERA elements that

must be taken into account are as follows:

Goal of recruitment: The goal of enterprise

recruitment has been clearly defined as “to fill a

vacancy”. Depending on the size and the type of

industry and organisation in which recruitment

is conducted, the number of vacancies and their

types may vary.

Problem: The problem of enterprise recruitment

reflects the potential/existing differentiation or

fragmentation between a number of recruitment

stakeholders’ interests across a number of

interest dimensions such as recruitware,

information, and timing (Alamro et al., 2018).

An enterprise recruitment problem is defined as

the problem frame (i.e. type of problem) that is

agreed on by all stakeholders as the most

problematic issue to be solved towards the goal

of recruitment.

Symptoms/Threats: There are a number of

symptoms or threats that are associated with the

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

240

enterprise recruitment problem and prevent the

goal of recruitment to be achieved. These are: no

engagement (i.e. when there is no action received

at all from the target agent); withdrawal (i.e.

when a target agent withdraw out of interaction);

and rejection (when a target agent clearly send a

rejection message to an offer). A recruitment

analyst must be aware of these symptoms/threats

and find the root causes (i.e. interest dimensions)

that lead to such actions.

Context: A major factor of successful sharing

and reuse of an ERBP is to capture the

knowledge of the business context or domain in

which a recruitment problem exists. The

business context can be recognised by a

combination of the specific recruitment problem

frame and the corresponding recruitment

solution (i.e. policies, actions, and software

specifications) to solve this type of problem

according to its goal of recruitment and

environment. It is very common that problem

owners characterise the problematic situations

as being of a known problem type or category

(Smith, 1989; Abd Rahman et al., 2011). Hence,

rather than representing and defining the current

situation as a whole, they define a problem by

matching the features of this situation to the

characteristics of well-known experienced

problems so facilitating the selection and

tailoring of recruitment policies, mechanisms,

and IT solution specifications. The environment

for ERBPs is composed of recruitment realms

(RRs) and is associated with an enterprise

overarching based on the interest levels and the

set of policies applied on each interest

dimension within these RRs. These sub-

elements will be explained in the next sections.

Stakeholders: A stakeholder can be any

individual, a group of individuals, or an

organisation with an interest or set of interests in

enterprise recruitment system. The stakeholders

of an ERBP populate the recruitment realms

(RRs) and interact with each other across

interest dimensions.

Solution: A solution in ERBP must be captured

in different levels of abstraction including

technological tools. However, information

systems such as recruitment system could

operate without the use of e-solution or simply

transform into e-space (Sharp et al., 2007;

Smalikiene and Trifonovas, 2012). Hence, the

solution in ERBP will be limited to four levels

of abstraction: Recruitment Problem Definition

(RPD), Early Requirements Definition (ERD),

Functional Requirements Definition (FRD), and

E-Recruitment Solution Specification (ERSS).

These four viewpoints of a solution were based

on the ex-MDA (Fouad et al., 2011).

The elements of the template provided by Buschmann

et al. (2007) and some new sections that we consider

necessary when integrating with the ERA elements

are described in the following texts:

Name: The name of ERBP should represent the

problem to be solved. The name must be also

unique and within the scope of this type of

ERBP.

Intent: This provides a short description of the

intended purpose of the ERBP.

Context: This section describes the generic

environment under which the ERBP should be

applied. This may include: (a) the type of

vacancies to be filled (job description and

specification); (b) the RRs involved in the

ERBP; (c) the set of stakeholders within each

RR; and (d) the general features and interactions

between RRs. This context can be specified by

context diagram.

Problem: This section describes the problematic

situation that has led to the necessity to apply the

corresponding solution, including: (a) the

threats/symptoms; (b) the forces (problem frame

and interest dimensions) that cause the problem

and guide the solution; and (c) the type of

interacting agents (whom to recruit (with))

because this will affect the recruitment

mechanisms of the solution.

Known cases: This section describes the real

cases of known recruitment incidents related to

the problem.

Solution: This section describes how the

problem is solved and how the threats associated

with filling job vacancies and forces are treated.

The solution will be expressed through the four

levels of abstractions used in the POCM-RAA:

RPD, ERD, FRD, and ERSS.

Considerations: This section describes the set of

key perceptions and impressions of all relevant

stakeholders about the solution given in the

ERBP.

Consequences: This section discusses the

benefits and drawbacks of the solution in

relation to the forces (interest dimensions) found

in the problem.

Known uses: This section describes the real

cases where the solution provided is used.

Related ERBP: This section gives references to

the ERBPs that solve similar problems, consider

similar contexts, or complement this ERBP.

Template-Driven Documentation for Enterprise Recruitment Best Practices

241

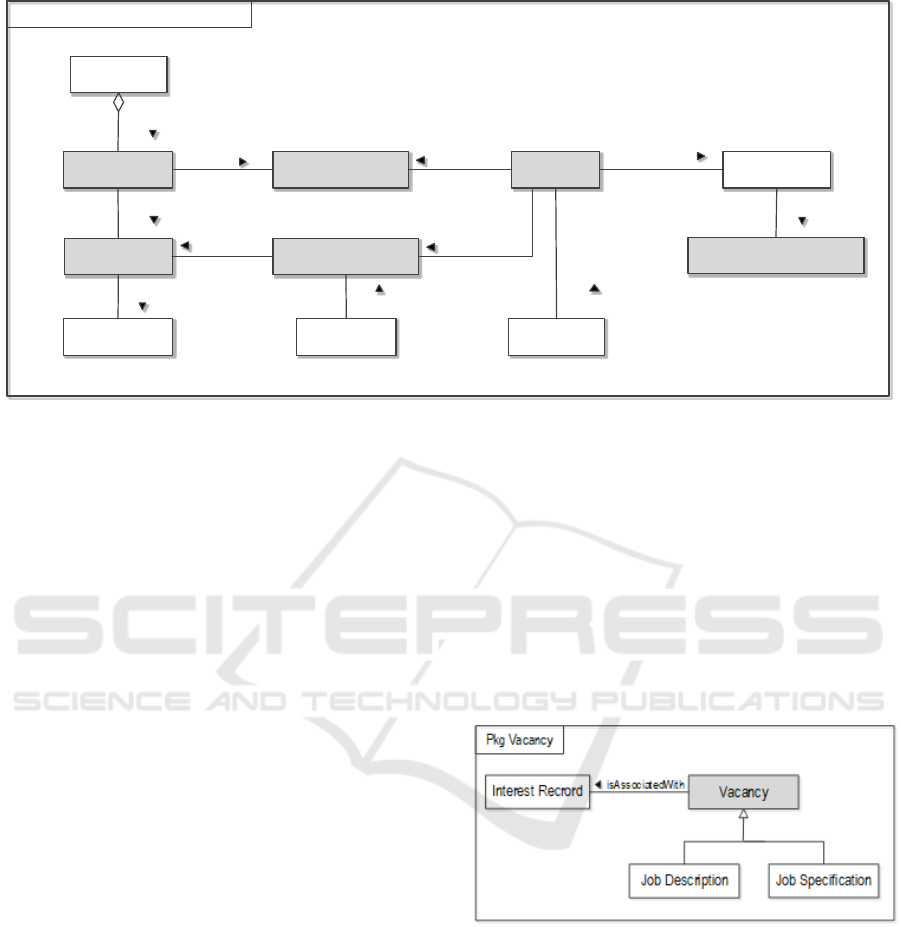

Figure 1: UML metamodel for ERBP template.

4.1 A Metamodel for ERBP Template

The ERBP template will include a wide range of

items describing an ERBP that solves an enterprise

recruitment problem in a specific context. To do this,

the ERBP template will integrate, in one cohesive

UML metamodel, both the ERA elements and all

elements of the template defined earlier. Figure 1

presents the metamodel of ERBP template that

defines the elements of ERA (shaded rectangle) and

the elements of the ERBP template (white rectangle

with *), as well as the relationships between them.

However, some of these elements are shared such as

context, problem, and solution.

In the next sections, the UML metamodel for

ERBP template will be complemented with a number

of UML diagrams to describe the details of each

element of the ERA (shaded rectangles) used in

Figure 1 to define and document the ERBPs.

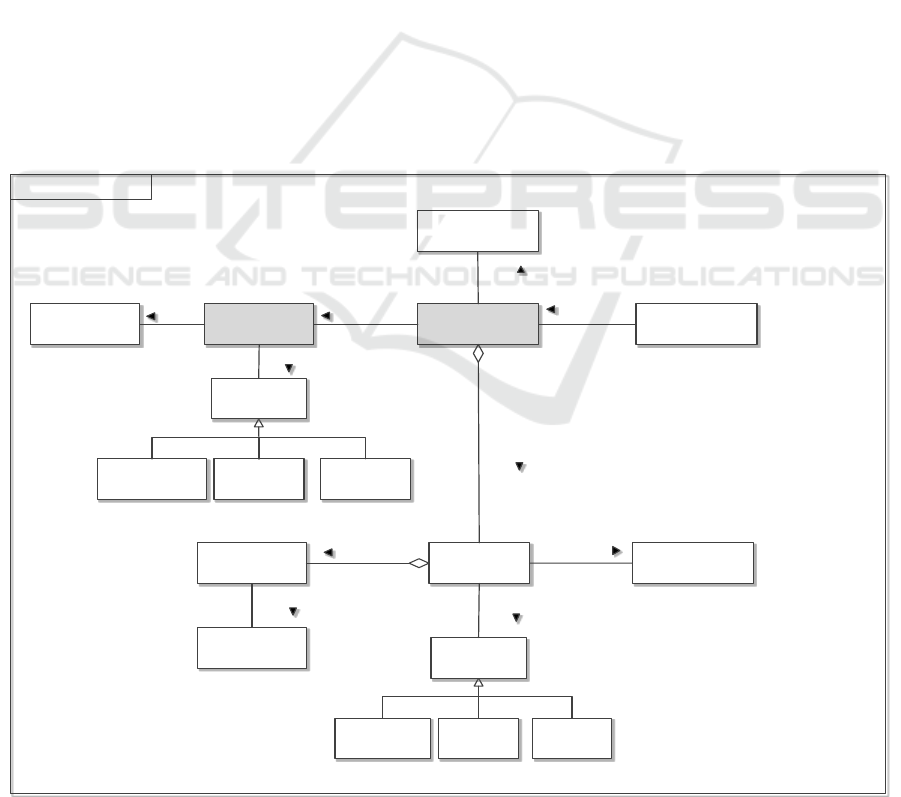

4.1.1 UML Metamodel for Vacancy

When building a recruitment system, organisations

should identify their job vacancies in order to

facilitate the recruitment analyst’s work. This

identification includes the job description (i.e. all the

job-oriented information about a specific job); and the

job specification (i.e. all employee-oriented

information required to fill a job). These information

indicate the importance that those job vacancies have

for organisations and the interest record that has to be

or factors so that when classifying jobs, the

organisations should seek support from a risk analysis

methodology.

The identification of job vacancies will facilitate

the setup of cost-effective policies that constitute the

interest record necessary to fill these vacancies. For

example, the ‘location of work’ of a job vacancy will

need recruitment policies related to the quality feature

“accessibility”; the ‘tasks involved’ will need

recruitment policies related to the quality feature

“familiarity”. However, there might be vacancy

elements that need a set of recruitment policies to be

considered. Figure 2 presents the metamodel of

vacancy.

Figure 2: UML metamodel for vacancy.

4.1.2 UML Metamodel for Context

The elements included in the context of ERBPs are:

The type of enterprise recruitment addressed in an

ERBP, the recruitment realms (RRs) involved in that

type of enterprise, and the interest record associated

with those realms. Figure 3 presents a UML

metamodel of the context elements and the

relationships between them.

islocatedIn

Context*

Intent*

Vacancy

isAssociated

Solution*

Problem*

attemptsToSolve

isAssociatedWith

Threats

Known Cases*

areBased

Consequences* Known Uses*

areRelatedTo

Considerations*

Stakeholders

resultIn

isAssociatedWith

areRelatedTo

Pkg ERBP Template

isAssociatedWith

isToFill

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

242

Figure 3: UML metamodel for context.

The Enterprise Levels

The enterprise can be addressed from different

perspectives or levels. According to Graves (2009),

these levels are the organisation level, the value-chain

level, the market level, and finally the extended level

where the enterprise includes everyone. In each level,

there will be a set of recruitment realms (RRs)

involved. These RRs are explained in the next

section.

Recruitment Realms (RRs)

RRs can be defined as logical and discrete entities that

partition the enterprise network. Based on the

definition of recruitment adopted in Alamro et al.

(2018), these RRs have the same interest dimensions

and quality features through which they interact.

Therefore, a set of different recruitment policies can

be applied in each RR.

In Figure 3, there are different types of realms

(TR) that can be found in enterprise recruitment.

These RRs, based on Alamro et al. (2018), are:

Recruiter: This realm consists of a recruiter or a

group of recruiters with the same purpose.

Recruiters typically conduct recruitment

activities. This realm is composed of the

following:

Locator: The one who typically define or

find where the potential applicants are.

Announcer: The one who prepares

recruitment message and selects one or a

set of methods to announce it to the

target applicants.

Inspector: The one who screens

applicants or their applications against a

set of requirements to discover if there is

anything wrong with them.

Examiner: The one who assesses the

things such as knowledge, skills, and

abilities that have been thought to the

applicant.

Offeror: The one who selects a candidate

and extends an offer for him.

Hirer: The one who signs the recruitment

contract with an applicant.

Context

Recruitment Realms

Recruiter

Hirer

Job Provider Qualification Provider

Control Level (CL)

composedOf

Announcer

Examiner

Offeror

Fully Controlled

Inspector

Externally ControlledNo Control

PkgContext

Applicant

Interest Record

Interest levels

associatedWith

Interest Sets

composedOf

composedOf

Enterprise

represents

Level

consistOf

consistsOf

MarketValue-ChainOrganisation Extended

Type (TR)

consistOf

Regulator CompetitorCommunity

Locator

Recruitment

Policies

associatedWith

Template-Driven Documentation for Enterprise Recruitment Best Practices

243

Applicant: This realm consists of one applicant

or a group of applicants with the same purpose.

An applicant typically seeks a job and apply for

it. Applicants could be internal as employees

inside the organisation; or external from the

outside. Applicants are the customer of recruiter

in case of value-chain enterprise.

Job Provider: This realm consists of one job

provider or a group of job providers with the

same purpose. Job providers are typically

responsible for the creation of a job vacancy, the

notification for filling, and the embarkation of

new recruits. Job providers are job suppliers in

the case of value chain enterprise.

Qualification Provider: This realm consists of

one qualification provider or a group of

qualification providers with the same purpose.

Qualification providers are those provide things

such as statements, references, reports or letters

that qualify an applicant to apply for a job.

Examples of this realm are schools, universities,

hospitals, or identity checkers. Qualification

providers are supplier of recruiter in case of

value-chain enterprise.

Regulator: This realm consists of one regulator

or a group of regulators with the same purpose.

A regulator is typically a person or organisation

whose job is to control recruitment-related

activities and make sure that they operate

according to official rules or law.

Competitor: This realm consists of one

competitor or a group of competitors with the

same purpose. A competitor typically a person

or company who is a rival against others.

Community: This realm consists of one person

or a group of persons with the same purpose.

The influence of such realm typically appears in

case of extended enterprise. Examples of this

realm are non-client, anti-client, or society as a

whole.

The RRs are also classified by their control level

(CL) for the recruiting organisation. Based on this

level of control, the recruitment policies applied in

each RR could change. These CLs are derived from

the work of Alwazae et al. (2015), as follows:

No control (NC): If the RR with no control, the

realm is not controlled by any organisation.

Hence, the recruiting organisation has no ability

to set or impose recruitment policies within that

realm. However, the policies and mechanisms of

this RR can be expected.

Externally controlled (EC): If the RR is

externally controlled, the RR is managed by

another organisation or partner. Hence, the

recruiting organisation has no ability to set

recruitment policies within the realm but it can

have a service agreement (agreed conditions) by

which a set of policies are agreed on.

Fully controlled (FC): If the RR is fully

controlled, the recruiting organisation has the

full ability to set or impose a set of recruitment

policies within the realm.

When classifying the RRs, two things have to be

considered: the TR that can be found in an enterprise

network, and their CL (who manages this type of

realm). Hence, the classification of RRs can be

defined as RR: TR X CL. These specific RRs can be

used to describe the different types of contexts in

which ERBPs are applied. Table 2 presents the

various types of RRs resulting from our classification

marked with (√).

Table 1: Classification of recruitment realms (RRs).

Type of

Realm (TR)

Control Level (CL)

No

Control

Externally

controlled

Fully

controlled

Recruiter

-

√

√

Applicant

√

√

√

Job Provider

√

√

√

Qualification

Provider

√

√

√

Regulator

-

√

-

Competitor

√

√

-

Community

√

-

-

The Interest Record

In ERBPs, the interest levels that are applied in all

RRs included in a specific context of enterprise form

the interest record needed for filling a vacancy. In

each RR, there will a set of interest levels which

determine the overall interest of that RR to interact

for filling a job vacancy. These interest levels are

reflected by the recruitment policies adopted in a

specific realm and by the corresponding set of actions

used in interaction. The recruitment policies applied

in each realm are defined in reference to the

recruitment problem type (frame) to solve (i.e.

interest dimensions as well as their interrelationships

and related quality features, see Alamro et al. (2018).

The problem types suffered in each realm can vary,

but the focus here will be on a set of problems that

can be suffered by all RR in common.

Given the definition of recruitment adopted in

Alamro et al. (2018) being a set of interactions, the

common problems of these interactions are related to:

the information exchanged (information dimension);

the timeframe of interaction (time dimension); the

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

244

duration or length of interaction (time dimension);

and the medium of interaction (recruitware

dimension). For each problem, there are some related

recruitment quality features that must be taken into

account by all RRs when defining recruitment

policies to solve such a problem. For instance, an

information-related problem is associated with

features such as information adequacy and accuracy;

a timeframe-related problem is associated with a

feature such as timeliness; a duration-related problem

is associated with a feature such as availability; and

finally a medium-related problem is associated with a

feature such as accessibility.

To establish the interest record for filling a job

vacancy in an enterprise context, the recruitment

analysts should maintain the interest sets of all RRs

included in the context. To maintain the interest set in

each recruitment realm, the recruitment analysts will

assign a set of appropriate recruitment policies to

each realm according to the problems suffered and

their related quality features taking into account the

dependencies between the problems themselves as

well as between RRs in the different levels of

abstractions.

The output of interest record is a set of numbers

that represent the interest sets (the set of interest

levels and the policies applied) for each RR included

in the context. These numbers or interest levels will

help recruitment analysts to select a course of

recruitment actions that fit to these levels. Moreover,

based on these numbers, recruitment analysts can

decide whether the ERBP is appropriate or not when

reusing.

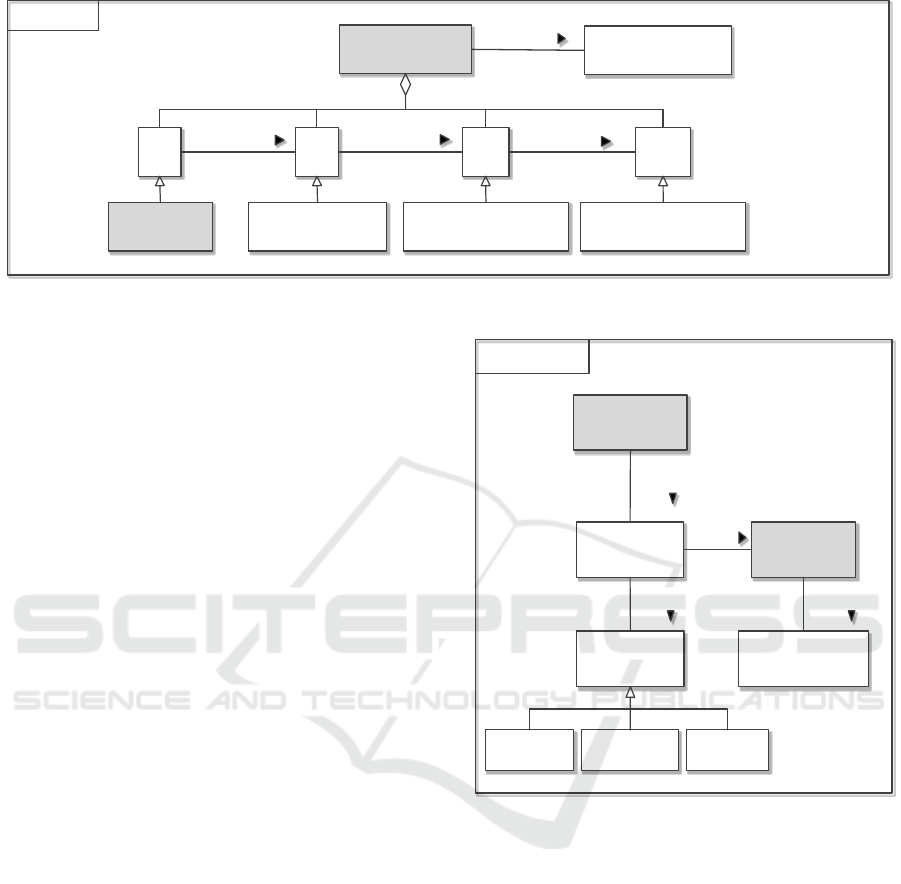

4.1.3 UML Metamodel for Problem and

Threats

Figure 4 shows a UML metamodel for the problem

and threats. The problem that the ERBP attempts to

solve must address the threats associated with filling

a job vacancy and the set of forces that enable those

threats. The threats, such as no engagement,

withdrawal, and rejection, stop filling of a vacancy

and result in some consequences. These

consequences should match the threats identified. The

forces consist of interest dimensions (recruitware,

information, and timing), their elements, and the

intervening relationships between these elements.

The problem lies in the conflict between these interest

dimensions and their elements when the RRs are

interacting.

Figure 4: UML metamodel for problem and threats.

Problem*

Dimensions

Threats

Interest Record

Consequences*

Pkg Problem & Threats

TimingInformationRecruitware

Type

consistOf

composedOf

associatedWith

RelationshipsElements

Quality Features

composedOf

associatedWith

areBasedOn

associatedWith

resultIn

RejectionWithdrawalNo engagement

Type

consistOf

associatedWith

Known Cases*

Template-Driven Documentation for Enterprise Recruitment Best Practices

245

Figure 5: UML metamodel for solution.

4.1.4 UML Metamodel for Solution

In Figure 5, the UML metamodel for solution defines

four solution viewpoints. The first is the RPD which

is related to the problem environment and model the

type of problem to solve. The other three ERD, FRD,

and ERSS are related to the solution environment and

modelled in three levels of system abstractions.

As can be seen in Figure 5, the RPD is used by the

recruitment analysts to capture the problem domain

knowledge and then define the enterprise recruitment

problem to solve. The ERD is used by the recruitment

analysts to define the early requirements of the

system without considering of the functional aspects

of a process. These early requirements are the

recruitment policies that the system solution enforce.

The FRD is used by the recruitment analysts to define

the functional and operational requirements of the

system. In this viewpoint, the recruitment

mechanisms and actions that the system should

perform based on the predefined policies are

captured. Finally, the ERSS is used by both the

business and software analysts to define the context

and specifications of e-recruitment solution. The four

models used in the UML metamodel for solution are

instantiated over the same set of RRs in a specific

context to build the solution for the enterprise

problem.

4.1.5 UML Metamodel for Stakeholders

Figure 6 shows the UML metamodel for stakeholders.

The ERBP should provide a qualitative evaluation

(set of considerations) of the solution from different

stakeholders’ perspectives according to the same set

of RRs in a specific context. When carrying out the

evaluation, the quality features of the Onto-RPD

artefact should be used for assessment.

Figure 6: UML metamodel for stakeholders.

5 DEMONSTRATION AND

EVALUATION OF ERBP

TEMPLATE

In this section, the demonstration and evaluation of

the ERBP template will presented.

5.1 Evaluation

The evaluation of the ERBP template was carried out

with a focus group consisting of 10 domain experts.

In preparing for the meeting, a full package including

the ERBP template, the five UML complementary

diagrams, and a questionnaire based on the defined

requirements along with the instructions of use were

Solution*

ERD FRD ERSS

Recruitment Polices Recruitment Mechanisms E-Solution Specifications

transformedTo

transformedTo

RPD

Problem*

transformedTo

Recruitment Realms

associatedWith

Pkg Solution

Stakeholders Considerations*

Pkg Stakeholders

Solution

relatedTo

Information Recruitware Timing

associatedWith

Interest

Diemensions

relatedTo

Recruitment Realms

associatedWith

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

246

sent to the participants. During the meeting, the

ERBP template, the practical problems that the ERBP

template was meant to address, and the defined

requirements by which this template is assessed were

all presented. Each expert was asked to comment on

the ERBP template and its elements. The discussion

was directed by a facilitator. During the discussion,

experts were asked to write down their comments on

the contribution of the ERBP template to the

requirements prescribed using the templates

provided. At the end, they were also asked to add their

suggestions and recommendation for improving the

ERBP template.

5.2 Results from the Evaluation

The key findings from the evaluation that is centred

on the requirements and characteristics of the ERBP

template are presented in section 3.2, are as follows:

Requirement 1: The ERBP template shall

consist of a complete set of ERBP elements.

Four experts confirmed that the ERBP template

covers all of the elements in ERBP. One of them

reported “the template is quit full. I can see all

key elements included”. Another expert

suggested some elements to be added to the

template such as date, keywords, and

technologies used.

Requirement 2: The ERBP template shall be

easy to use for sharing and reuse. Two experts

reported that the description of the elements and

their relationships are clear and straight-

forward. However, two other experts stated that

the template is very complex to understand

particularly interest record and levels. One of

them stated that “an example of application is

needed”. Another stated that “some

reformulation might be needed”. These point up

the need of applying the ERBP template to some

case studies as someone might not be able to

estimate the comprehensiveness and easiness of

use until the application in real-life cases.

Requirement 3: The ERBP shall support both

the creation of high quality ERBPs and the

evaluation of already exiting BPs. According to

three experts, the ERBP template could be used

for both these purposes. They confirmed that the

template represents a good foundation to

structure and articulate ERBPs. One expert

stated “the template gives a concrete structure

for what elements you have to document, and it

makes ERBP easier to use”. Some experts

criticised the template as being hard to use and

needs some time and training to do that. Other

experts stressed the need of a methodology by

which such ERBP template can be shared and

reused.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, an ERBP template for is designed for a

proper documentation of ERBPs. The template was

represented using a precise metamodel with five

complementary UML diagrams. The findings of the

evaluation of ERBP template is encouraging. The

future work will focus on applying the ERBP

template into real-life case studies to assess its

comprehensiveness and usability.

REFERENCES

Abd Rahman, A.A. Sahibuddin, S. and Ibrahim, S. 2011. A

study of process improvement best practices.

Information technology and multimedia (ICIM),

International Conference on IT & Multimedia at

UNITEN (ICIMU 2011) Malaysia, 1-5.

Ahamed, S., Adams, A., 2010. Web recruiting in

government organisations: A case study of the Northern

Kentucky / Greater Cincinnati Metropolitan Region,

Public Performance & Management.

Alamro, S., Dogan, H., Cetinkaya, D., Jiang, N. and Phalp,

K., 2018. Conceptualising and Modelling E-

Recruitment Process for Enterprises through a Problem

Oriented Approach. Information, 9 (11), 269.

Alwazae, M. Perjons, E. and Johannesson, P. (2015).

Applying a template for best practice documentation.

The 3rd Information Systems International Conference,

November, 2-4, Surabaya, Indonesia.

Carless, S.A., Wintle, J., 2007. Applicant Attraction: The

role of recruiter function, work-life balance policies and

career salience. International Journal of Selection and

Assessment, 15(4), pp. 394-404.

Buschmann, F., Henney, K., Schmidt, D.C. 2007. Pattern

Oriented Software Architecture. On Patterns and

Pattern Languages, vol. 5. Wiley, Chichester.

Fouad, A., 2011. Embedding requirements within the

Model Driven Architecture. PhD Thesis, Bournemouth

University.

Gartner. 2008. Gartner Clarifies the Definition of the Term

'Enterprise Architecture'. Gartner research. ID

Number: G00156559.

Graupner, S. Motahari-Nezhad, H.R. Singhal, S. and Basu,

S. 2009. Making processes from best practice

frameworks actionable. Enterprise Distributed Object

Computing Conference Workshops, 13th IEEE, 1-4

September, 25-34.

Hanafizadeh, P. Moosakhani, M. and Bakhshi, J. 2009.

Selecting the best strategic practices for business

Template-Driven Documentation for Enterprise Recruitment Best Practices

247

process redesign. Business Process Management

Journal, 15 (4), 609-627.

Investopedia. 2016. Best Practice. Accessed (2016-07-15)

at https://www.Investopedia.com/terms/best_practice

Jashapara A. Knowledge Management: An Integrated

Approach. 2nd Edition. Pearson Education, Harlow,

Essex; 2011.

Johannesson P., Perjons E., 2014. An introduction to design

science. Springer International Publishing,

Switzerland.

Madia, S. 2011. Best practices for using social media as a

recruitment strategy. Strategic HR Review, vol. 10, no.

6, pp. 19–24, 2011.

Mansar, S. and Reijers, H. 2007. Best practices in business

process redesign: Use and impact. Business Process

Management Journal, Emerald Group Publishing

Limited, 13 (2), 193-213.

Molina, A., Medina, V., 2003. Application of enterprise

models and simulation tools for the evaluation of the

impact of best manufacturing practices implementation.

Annual Reviews in Control, 27 (2003) 221–228.

Motahari-Nezhad HRM, Graupner V, Bartolini C. 2010. A

framework for modelling and enabling reuse of best

practice IT processes. Business Process Management

Workshops; 2010, p. 226-231.

Penaranda, N., Mejia, R., Romero, D. and Molina, A. 2010.

Implementation of product lifecycle management tools

using enterprise integration engineering and action-

research. International journal of computer integrated

manufacturing, 23 (10), 853-875.

Renzl, B. Matzler, K. and Hinterhuber, H. 2006. The Future

of Knowledge Management. Palgrave Macmillan, New

York.

Sharp, H., Rogers, Y., and Preece J., 2007. Interaction

Design: Beyond Human–Computer Interaction.

Simard, C. and Rice, R.E. 2007. The practice gap: Barriers

to the diffusion of best practices. In McInerney, C. R.

and Day R. E. Ed., Re-Thinking Knowledge

Management: From Knowledge Objects To Knowledge

Processes, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer-

Verlag, 87-124.

Smith, G., 1989. Defining managerial problems: A

Framework for Prescriptive Theorizing. Management

Science, vol. 8, pp. 963-981.

Stephenson, C. and Bandara, W. 2007. Enhancing Best

Practices in Public Health: Using Process Patterns for

Business Process Management. In Proceedings ECIS

2007 - The 15th European Conference on Information

Systems, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2123-2134.

Vallejo, C, Romero, D. and Molina, A. 2012. Enterprise

integration engineering framework and toolbox.

International journal of production research, 50 (6),

1489-1511.

Vesely A. Theory and methodology of best practice

research: A critical review of the current state. Central

European Journal of Public Policy, vol. 2; p. 98-117.

Zachman, J., 2008. The concise definition of the Zachman

framework, link: https://www.zachman.com/about-the-

zachman-framework.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

248