The Effects of Digitalisation on Accounting Service Companies

Tommi Jylhä

1

and Nestori Syynimaa

2

1

ICT Department, Central Finland Health Care District, Jyväskylä, Finland

2

Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: Digitalisation, Automation, Robotisation, Artificial Intelligence, Innovation, Diffusion.

Abstract: Rapidly expanding digitalisation profoundly affects several jobs and businesses in the following years. Some

of the jobs are expected to disappear altogether. The expanding digitalisation can be seen as an example of

the diffusion of innovations. The world has witnessed similar developments since the early years of

industrialisation. Some of the sectors that will face the most disruptive changes are accounting, bookkeeping,

and auditing. As much as 94 to 98 per cent of these jobs are at risk. The purpose of this study was to find out

how digitalisation, automation of routines, robotics, and artificial intelligence are expected to affect the

business structure, organisations, tasks, and employees in Finland in the following years. In this study, 11 of

the biggest companies providing outsourced accounting services in Finland were interviewed. According to

the results, the development of the technology will lead to substantial loss of routine jobs in the industry in

the next few years. The results of the study will help estimate the changes the rapidly developing technology

will bring to the industry in focus. The results will also help the organisations in the industry to learn from the

experiences of the other organisations, see the potential benefits, and prepare for the forthcoming change

through strategic choices, management, and personnel training.

1 INTRODUCTION

The effects of technology development on the whole

industry sectors is not a new phenomenon. For

instance, in Northern-England in the late 1700’s

people were afraid that the new sewing machines

would danger their jobs and income (Krugman,

2013). The speed of new technological innovations is

higher than ever. Some scholars argue that the highest

growth in productivity is still ahead (Pohjola, 2014).

Contrary to this, some scholars see that the highest

increase in productivity is already passed, and

technology development is now focused on

entertainment and free-time (Gordon, 2012).

The purpose of this study was to find out how

digitalisation, automation, robotics, and artificial

intelligence are expected to affect the business

structure, organisations, tasks, and employees in

Finland in the following years.

The paper is structured as follows. This section

introduces the subject area of the paper, including the

accounting industry in Finland. The second section

introduces the background theories of the study. The

research method is described in section three. The

results of the study are provided in section 4. Finally,

section 5 concludes the paper with discussion and

directions for future research.

1.1 Technology Development Effect on

Jobs

The developing technology is expected to obviate a

remarkable portion of jobs in the near future.

According to 352 Artificial Intelligence (AI)

researchers, there is 50 per cent chance that AI will

beat the performance of human beings in 45 years and

replacing the human workforce totally in 120 years

(Grace et al., 2018). In the United States, even 47 per

cent of the jobs can be automated during the next two

decades (Frey and Osborne, 2017). In Finland, the

percentage is 35 and in Norway 33 (Pajarinen et al.,

2015). Especially the low-wage and low-skill

occupations are at risk (ibid).

The revolutionary changes in society caused by

developing technology have been witnessed to

happen in 40 – 50-year cycles as illustrated in Figure

1. We are currently on the verge of the sixth

Kondratieff cycle: Intelligent technologies (Wilenius,

2014).

502

Jylhä, T. and Syynimaa, N.

The Effects of Digitalisation on Accounting Service Companies.

DOI: 10.5220/0007808605020508

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2019), pages 502-508

ISBN: 978-989-758-372-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Figure 1: Modern economies fluctuate in a cycle of 40-50

years (Wilenius, 2014, p. 3).

The new technology does not cause changes in

production per se; massive changes in organisations

are also needed. Innovations and organisational

changes together are causing so-called skill-biased

technical change (SBTC). Cognitive skills have a

high effect on all changes in general, but especially

when the change includes the adoption of new

technology (Bresnahan et al., 2002).

1.2 Accounting Business in Finland

In 2015, two-thirds of the Finnish accounting

companies had more than 10 employees (see Table 1).

Table 1: Distribution of sizes of member organisations of

the Association of Finnish Accoutning Firms

(Taloushallintoliitto, 2019).

Size (persons) Percentage

1 – 2 5 %

3 – 4 10 %

5 – 9 22 %

10 – 20 25 %

> 20 38 %

In 2016, there were 4 235 companies in the

industry, with 11 702 employees (see Table 2). The

total turnover of the industry was 970 million euros.

The number of companies is decreased 2 per cent

since 2014 and the number of employees 3 per cent.

At the same time, the total turnover has increased by

one per cent. Moreover, turnover per employee has

raised 9 per cent from 76 000 euros to 83 000 euros.

Table 2: Accounting industry in Finland

(Taloushallintoliitto, 2019).

Year Companies

Turnover

(million euros)

Personnel

2014 4333 915 12 017

Year Companies

Turnover

(million euros)

Personnel

2015 4295 958 12 253

2016 4235 970 11 702

The accounting industry has centralised in

Finland in the last decade. Smaller companies have

typically run by owners and a small number of

employees. Due to retirement, companies are

acquired by bigger companies.

Currently, the accounting industry in Finland is

advancing from digital accounting towards AI and

robotisation as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Development of digital accounting in Finland

(adapted from Lahti and Salminen, 2014, p. 27).

1.3 Key Concepts

Digitalisation can be defined as “the use of digital

technologies to change a business model and provide

new revenue and value-producing opportunities; it is

the process of moving to a digital business” (Gartner,

2019).

Automation is not a synonym to digitalisation.

Digitalisation is creating value by introducing

something totally new whereas automation is

improving something existing (Moore, 2015).

Robotisation is a sub-area of automation. A robot

can be defined as a mechanical device that works in

physical world (Linturi and Kuittinen, 2016). Robotic

process automation, however, includes also software

robots (Willcocks et al., 2015).

2 DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS

There are at least five types of innovations that can be

identified from the literature (Schumpeter and Fels,

1939):

1. The launch of a new product or a new species of

an already known product,

2. Application of new methods of production or

sales of a product (not yet proven in the industry),

1990's 2000's 2010's 2020's

Paperless

bookkeeping

Electronic

accounting

Digital

accounting

AI and

robotics

The Effects of Digitalisation on Accounting Service Companies

503

3. The opening of a new market (the market for

which a branch of the industry was not yet

represented),

4. Acquiring new sources of supply of raw material

or semi-finished goods, and

5. New industry structure such as the creation or

destruction of a monopoly position.

As such, the innovation does not need to be new per

se, as long as it has some novelty value to the adopter.

Innovations are usually technological, consisting of

typically two components; physical device and

knowledge, i.e., software (Rogers, 2003).

Innovation adoption and implementation

spreading are commonly called diffusion. Before the

diffusion starts, important decisions are made and

operations performed, which leads to the birth of the

innovation. This process is called to innovation-

development process (Rogers, 2003):

1. Needs or problems,

2. Research (basic and applied),

3. Development,

4. Commercialisation,

5. Diffusion and Adoption,

6. Consequences

People and organisations are adopting innovations in

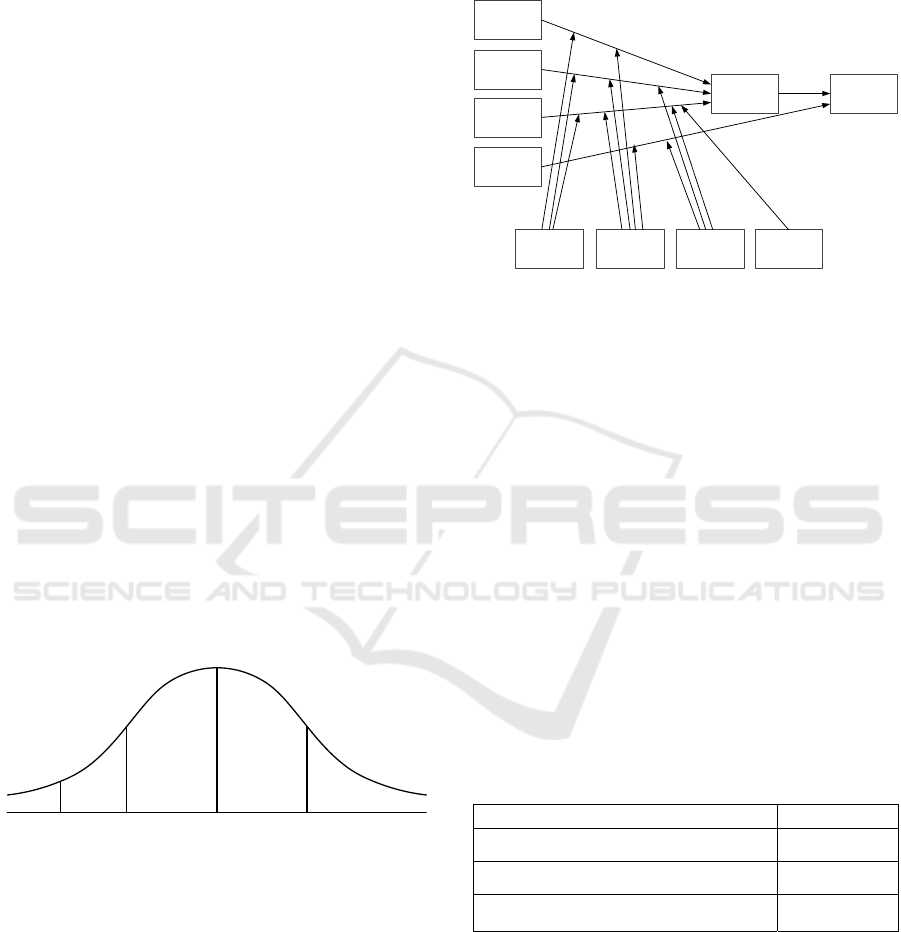

different phases as illustrated in Figure 3. Typically,

early adopters have higher education and social status

than the late adopters. Moreover, early adopters are

more emphatic and resilient, and they are pursuing

better education and more respected jobs. (Rogers,

2003).

Figure 3: Adopter categorisation on the basis of

innovativeness (adapted from Rogers, 2003, p. 281).

When adopting an innovation, the following

decision process is used (Rogers, 2003):

1. Knowledge,

2. Persuasion,

3. Decision,

4. Implementation, and

5. Confirmation.

In Information Systems (IS) science, the persuasion

and decision phases have been proven to be explained

by the unified theory of acceptance and use of

technology (UTAUT) by Venkatesh, Morris, Davis

and Davis (2003). The UTAUT is illustrated in Figure

4.

Figure 4: Unified theory of acceptance and use of

technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

3 RESEARCH METHOD

In this paper, the qualitative research approach (see

Kvale, 1996) was chosen, as we are trying to

understand the phenomenon of digitalisation. The

empirical data was gathered using semi-structured

interviews. The questions were formed based on three

themes as listed in Table 3. The first theme contained

questions about organisations’ current state and

experiences of digitalisations. The second theme

contained questions related to organisations’ goals

and targets toward digitalisation. And finally, the

third theme contained questions about how the

organisations’ see how the digitalisation, automation,

robotics, and AI will affect the organisations and the

accounting industry.

Table 3: Interview themes and number of questions.

Theme # questions

Organisation’s current state and experience 10

Organisation’s goals 5

Effects of digitalisation, automation,

robotics, and artificial intelligence

7

The interviewed organisations were selected

using a non-probabilistic sampling method:

purposive sampling. The purpose was to include the

biggest companies from Finland. The companies

were found using the accounting company search at

https://taloushallintoliitto.fi, the Largest Companies

search at http://www.largestcompanies.fi,

companies’ web sites and authors knowledge of the

Early

Adopters

13.5 %

Early

Majority

34 %

Late

Majority

34 %

Laggards

16 %2.5 %

Innovators

Gender Age Experience

Voluntariness

of Use

Performance

Expectancy

Effort

Expectancy

Social

Influence

Facilitating

Conditions

Behavioral

Intention

Use

Behavior

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

504

industry. To increase the reliability of the research,

also public sector accounting organisations

(municipality and government-owned) were

included.

In total, 15 organisations were contacted, from

which of three did not response at all. One of the

contacted organisation declined to attend the research

appealing to trade secrets. The statistics of the

remaining 11 organisations are listed in Table 4. Each

organisation was interviewed once.

Table 4: Interviewed organisations.

Org.

Turnover

(million euros)

# employees

A 10 – 20 < 100

B > 40 > 500

C > 40 > 500

D < 10 < 100

E 20 – 40 > 500

F > 40 300 – 500

G 20 – 40 300 – 500

H < 10 < 100

I 10 – 20 100 – 300

J < 10 100 – 300

K > 40 > 500

From each organisation, a senior-level executive,

such as CIO, was interviewed using Skype. The

interviews were recorded and transcribed. The

lengths of interviews were from 19 to 66 minutes with

an average of 38 minutes. The interviews were

analysed using the directed content analysis (see

Hsieh and Shannon, 2005).

4 RESULTS

In this section the results of the analysis of interviews

are described. The quotes are translated from Finnish

so that the content would remain as close to original

as possible. The code in the parenthesis next to the

quotes refers to the interviewed person.

4.1 Organisations’ Current State and

Experience

Digitalisation, automation, robotics, and artificial

intelligence (DARAI) is seen as an opportunity by all

respondents: “definitely an opportunity. The threat is

always associated with new technologies, but the

positive effects are higher.” (I8). Eight respondents

said that they are using automation. Automation is

used inside applications, whenever possible. Between

the applications, manual tasks are replaced by robots:

“if we need automation between multiple

applications, the robot is the only option.” (I6).

Artificial intelligence is only entering the industry:

“AI is still the future” (I3), “It is the fact that only a

few have advanced from software robotics to AI”

(I4). One of the respondents said that they are using

AI on a daily basis: “We are using AI in customer

services – for instance applying accounting rules,

filling employee rules, memo vouchers, and

reconciliation” (I2). A totally new theme was

analytics: “When we see all the data, we can analyse

it and serve our customers even better” (I3).

Six respondents said that they have positive

experiences with using new technologies. Employee

resources could have been focused to more

specialised tasks, as robots take care of routine tasks.

“there is not many who is longing for the past where

you need to do things manually” (I7).

Using the new technologies have shown to

customers as “faster response times” (I6). Accounting

is also always up-to-date and provides real-time data

for decision making. New technologies are lowering

costs as manual tasks are replaced by the technology:

“it takes some time, but as we get the robot capacity

to different processes, it leads to lower prices to

customers” (I2). The technology also raises the

quality, as “the less the manual work, the less the

errors” (I4).

Most of the customer feedback is related to

change resistance: “for older customers, these new

systems are more challenging, and they are not so

keen to use these systems” (I7). “But this is rather

marginal, as soon as we can show the benefits, the

resistance is gone. Or not gone, but we can proceed.”

(I8). The unreliability of the new technology has also

caused some feedback: “of course there are some

bugs in the beginning, which irritates customers, but

they won’t notice them on later stages” (I1).

The respondents have had positive experiences on

robotics: “I thought that robotisation would be

expensive, but software robots are actually very cost-

effective and ROIs relatively short” (I2). There were

also some negative experiences: “cloud services are

sometimes slow which frustrates. These new systems

have also been surprisingly error-prone when

compared to old systems. And because everything

runs on third-party services, our IT can’t do anything

but wait.” (I7).

The biggest challenges are also related to the relia-

The Effects of Digitalisation on Accounting Service Companies

505

bility of the new technology: “there might be

situations, where one robot stops, many others will

stop too” (I11). Some respondents were surprised at

how slow the implementation phase could be. The

processes needed to be described in detail, as the

robots can only do what they have been instructed to

do: “you really need to describe every single move”

(I5). Describing the processes has sometimes been

also beneficial: “there have been changes to almost all

processes, as we had to think why we have done this

way and is this step even necessary” (I5).

Experiences on how employees react to new

technologies were contradictory. For instance, “some

may see the removal of routine work extremely

positive”, while some fear to lose their jobs.

Ten respondents said that there had been no

effects on the number of employees. However, the

new technology prepares organisations for forth-

coming massive retirements in Finland: “certain tasks

are disappearing, and as people are retiring, we won’t

necessarily need to hire a new employee” (I6). Future

employees likely need to know more about

robotisation than accounting.

4.2 Organisations’ Goals

All respondents have some goals on using new

technologies. For instance, “we have 50 targets

waiting for implementation” (I2), “there are 40 items

on our robotization backlog” (I6), and “we need to

robotise 50 tasks during this year” (I11).

Six respondents had plans for using AI, although

only part of them in the near future: “we are currently

starting an AI-project and we will use it in two use-

cases” (I9).

Seven respondents said that they are currently

using new technologies to improve their current

services: “that is why we are using robotics, as it is

the way to improve our efficiency” (I11).

Only one respondent had not set measurable

targets for using the new technology. Four

respondents indicated having set targets for savings

on labour: “we have, of course, set targets for

efficiency” (II5), “we measure the saved working

hours” (I3). Some also had numerical targets for

robotisation: “we have now 25 robots, in five years

there will be quite a lot” (I2).

The effects of new technology on organisations’

strategies are, and have been, eminent: “it is in the

centre of our strategy” (I2), “it is kind of support

beam, which has to work so that we are efficient and

are able to answer to our customers’ needs” (I8).

4.3 Effects of Digitalisation,

Automation, Robotics, and

Artificial Intelligence

Almost all respondents mentioned a remarkable

change in employees’ duties: “as soon as these

robotisations are implemented, people’s jobs are

changing toward robot controllers, specialists, and

consultants” (I2). The number of specialist type of

duties is increasing: “in the future, being an

accountant is not just reconciliation of accounts, but

more like analysing and dealing with exceptions – as

robots are not good at it” (I6).

Only three respondents said that the new

technology would decrease the number of employees

in the future: “some are not able to work in new roles

so those may lose their jobs. But it is more due to

changing role, as the growth takes care that there is

enough work to do in other roles” (I5). Others see the

reduction of employees eminent: “in the future, these

need to be done with less staff” (I6) and “we have

estimated that we can still automate 30 – 50 per cent

of our processes” (I9). The new technology can also

be used to deal with the retirement: “we need to pay

attention to retirement during the next three to five

years and compensate that using robotisation” (I2).

What comes to the accounting industry, the

respondents had fewer opinions. However, most of

the respondents indicated that the labour needs would

decrease in the industry “definitely” (I3): “I believe

that the number of staff will remarkably decrease, as

you can generate the same turnover with fewer

people” (I8). Some saw that automation and

robotisation remove the need for recruiting new

employees: “it is balancing with the resources as do

you need to hire a new employee if someone changes

to other employer or retires” (I6).

Accounting industry in Finland has been

consolidating in the last decade. The new technology

may change the markets: “it is possible that due to

digitalisation, new players may enter the market the

same way Uber did. Maybe not during the next three

years but in five. I think that even new global players

are possible” (I2).

All except two of the respondents believe that

their position in market will remain the same or gets

even better: “we are looking for and are pursuing for

growth” (I3), “I’m very confident about our market

share” (I4), “naturally, we hope that our market share

increases” (I7), and “we are leaders in developing, we

are widely using the new technology, and we have

specialised knowledge” (I8). Some reminded that the

continuous development is needed to even keep their

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

506

current market share: “we can’t rest on our oars, we

need to keep going” (I8).

Customers are expecting the usage of the new

technological advancements: “it is the premise of our

customers to use the new technology, as that is what

we are representing in the first place” (I8).

New technologies are affecting the unit prices of

the industry: “the price we can get from our customers

is decreasing all the time, so all you can do is to be

more productive” (I1). “At best, the prices have

dropped to half during the past five years” (I1).

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Conclusions

There has been a strong tendency to centralisation in

the accounting industry in Finland for many years.

The interviewed organisations are expecting that the

centralisation trend will continue. Another clear trend

is the usage of new technology to increase

productivity. The smaller organisations are not able

to invest in new technologies and consequently, to the

price competition. Usually, in many industries, the

revolutionary change is caused by a global player

using a scalable business model (Ilmarinen and

Koskela, 2015). However, only one interviewed

organisation anticipated the coming of such a global

competitor. This may be due to very conservative and

traditional industry, strongly regulated by local laws.

The technology was anticipated to lead to a

reduction of the workforce in the industry, as the

literature suggested (Frey and Osborne, 2017).

However, the large scale retirement was seen to ease

the pressure for the reduction.

Technological change was seen eminent: if the

organisation does not adopt new technology, the

continuity of the business is in danger. All

interviewed organisations were at least in the

digitalisation phase (see Lahti and Salminen, 2014).

Some were already proceeded to the next phase, AI

and robotics. The results indicate that this phase

should be divided to two, as many of the interviewed

organisations were already using robotics, but the AI

was still seen as the future. There were no differences

between the public and private sector organisations.

In this study, the innovation diffusion and

UTAUT theories were used as guiding background

theories. Thus, the theories were not tested in this

study per se. However, the usage of the new

technologies in the accounting industry in Finland

seems to follow the innovation diffusion theory.

According to our study, the new technology is

adopted especially by the larger organisations aiming

for growth. As such, they can be categorised as early

adopters. The smaller companies, typically

entrepreneurs, don’t have resources or even eagerness

to adopt new technology. As such, they can be

categorised as a late majority or even laggards. The

reasons for adopting new technologies seems to

follow well the UTAUT model. The new technology

is seen beneficial to organisations: it will make

organisations more productive. Moreover, the social

pressure caused by the competition was clearly

affecting technology adoption.

5.2 Implications

Our study has both scientific and practical

implications.

For science, our study provides support for the

innovation diffusion theory and UTAUT: they seem

to explain well how the new technology is adopted in

the accounting industry in Finland. Our findings

indicate that the last development phase (AI and

robotics) by Lahti and Salminen (2014) should be

split.

For practice, our study shows that adopting new

technologies is eminent for survival in the accounting

industry in Finland. Thus, the organisations should

invest in the new technology to increase their

productivity to match the current and future

competition. The loss of routine jobs in the

accounting industry is inevitable. However, the new

technology will create a new kind of jobs, requiring

totally different skillsets. There is also a slight chance

that a global competitor may enter the Finnish

accounting sector in the near future.

5.3 Limitations

The interviewed organisations represented the largest

organisations of the industry in Finland. This has

likely caused some bias to the results. The research

used innovation diffusion and UTAUT theories as

background theories. However, the theories were not

tested in this study.

5.4 Directions for Future Research

The results of this study should be verified in similar

settings in other countries to increase its validity.

Also, studying also the smaller Finnish organisation

might provide interesting evidence about the

accounting industry as a whole.

Another interesting area for future research would

be to properly assess how the innovation diffusion

The Effects of Digitalisation on Accounting Service Companies

507

and UTAUT theories explain the digitalisation in the

studied industry.

REFERENCES

Bresnahan, T. F., Brynjolfsson, E., & Hitt, L. M. (2002).

Information technology, workplace organization, and

the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence. The

quarterly journal of economics, 117(1), 339-376.

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of

employment: how susceptible are jobs to

computerisation? Technological forecasting and social

change, 114, 254-280.

Gartner. (2019). IT Glossary. Retrieved from

https://www.gartner.com/it-glossary

Gordon, R. J. (2012). Is US economic growth over?

Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.

Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/

w18315.pdf

Grace, K., Salvatier, J., Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Evans, O.

(2018). When will AI exceed human performance?

Evidence from AI experts. Journal of Artificial

Intelligence Research, 62, 729-754.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches

to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health

Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

Ilmarinen, V., & Koskela, K. (2015). Digitalisaatio:

Yritysjohdon käsikirja. Helsinki: Talentum.

Krugman, P. (2013). Sympathy for the Luddites. New York

Times, 13, 118.

Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: An introduction to qualitative

research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, California:

Sage Publications, Inc.

Lahti, S., & Salminen, T. (2014). Digitaalinen

taloushallinto. Helsinki: Sanoma Pro.

Linturi, R., & Kuittinen, O. (2016). Digitaalinen tietopohja

sekä robotisaation vaikutukset In L. Sarlin (Ed.),

Robotiikan taustaselvityksiä (pp. 67-90). Helsinki:

Liikenne- ja viestintäministeriö. Retrieved from

https://www.lvm.fi/documents/20181/877203/Robotii

kan+taustaselvityksi%C3%A4/b1b9f5d6-4f1f-436a-

84c9-eb42da4f81e2.

Moore, S. (2015). Digitalization or Automation - is There a

Difference? Retrieved from https://www.gartner.com/

smarterwithgartner/digitalization-or-automation-is-

there-a-difference/

Pajarinen, M., Rouvinen, P., & Ekeland, A. (2015).

Computerization threatens one-third of Finnish and

Norwegian employment. Etla Brief, 34, 1-8.

Pohjola, M. (2014). Suomi uuteen nousuun: ICT ja

digitalisaatio tuottavuuden ja talouskasvun lähteinä.

Helsinki: Teknologiateollisuus Ry.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5

th

ed.).

New York: Free Press.

Schumpeter, J. A., & Fels, R. (1939). Business cycles: a

theoretical, historical, and statistical analysis of the

capitalist process (Vol. 2): McGraw-Hill New York.

Taloushallintoliitto. (2019). Tilitoimistoala Suomessa.

Retrieved from https://taloushallintoliitto.fi/tietoa-

meista/tutkimuksia-ja-tietoa-alasta/tilitoimistoala-

suomessa

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D.

(2003). User acceptance of information technology:

Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

Wilenius, M. (2014). Leadership in the sixth wave—

excursions into the new paradigm of the Kondratieff

cycle 2010–2050. European Journal of Futures

Research, 2(1), 36. doi:10.1007/s40309-014-0036-7

Willcocks, L. P., Lacity, M., & Craig, A. (2015). The IT

function and robotic process automation. Retrieved

from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64519/1/OUWRPS_15_05

_published.pdf.

ICEIS 2019 - 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

508