Security Issues of Scientific based Big Data Circulation Analysis

Anastasia Andreasyan

1 a

, Artem Balyakin

2 b

, Marina Nurbina

2 c

and

Alina Mukhamedzhanova

3 d

1

Open Law Limited, 9, Vetoshnyi lane, Moscow, Russia

2

National Research Center Kurchatov Institute, 1, ac. Kurchatov sq., Moscow, Russia

3

Federal State Budgetary Institution of Higher Education "Russian State University of Justice" 69,

Novocheremushkinskaya St., Moscow, Russia

Keywords: Big Data, Security Issues, Scientific Field, Legislation, Sensitive Data, Open Data, GDPR, Megascience.

Abstract: The paper deals with legal issues arising from the need to regulate Big Data. For the purpose of this study it

is suggested that aspects of legal definition of Big Data should be considered, as well as its classification, and

analysis of risks in the global experience of legal regulation of Big Data. The authors believe that in the

context of onrush technology it is extremely important to strike the balance, protect sensitive data, and do not

bar from technological development, taking into account socio-economic impact of Big Data technology. We

stress, that it is more important to control the application of Big Data analysis, rather than the information

itself used in data sets.

1 INTRODUCTION

The modern world increasingly relies in its

development on progressive technology, and society

is being digitized at present. Progressive digital

technology used in various spheres - from IT to

medical research - offers solutions to the most

complex modern challenges. Once it became possible

to analyse large amounts of data, such concepts as

“Big Data” emerged.

Firstly, Big Data were received in operating a

scientific installation, namely the Large Hadron

Collider. Currently scientific projects in the

“megascience” category remain one of the key

“suppliers” of Big Data.

Besides, the amount of Big Data to be received in

the near future from the Large Hadron Collider alone

is predicted to surpass the same received from non-

scientific sources.

Thus, despite the fact that the largest amount of

Big Data is received from scientific installations in

the “megascience” category, Big Data are also

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9511-2624

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8655-7998

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8063-9706

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5050-2426

receivable in other areas. For example, Big Data are

widely used in advertising and sales, which in part

enabled such technological and economic giants as

Amazon, Google, and Facebook to form and prosper.

The development rates and the level of involvement

of Big Data in their activities raise public concerns. It

is worth noting that the 2018 editorial of The

Economist calls on the governments of all countries

to invigorate antimonopoly measures to regulate

digital economy markets, otherwise irreparable

damage will be done: the digital economy will no

longer be a market economy, but will be controlled

by a group of corporate monopolies having market

power which is unavailable to 20th century

monopolies and the governments of developed

countries (https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/

21735021-dominance-google-facebook-andamazon-

bad-consumers-and-competition-how-tame, 2018).

Significantly, the economy is not the only sphere

where Big Data are used; currently the active

integration in medicine, banking, public

administration, taxes, cellular communication, and

168

Andreasyan, A., Balyakin, A., Nurbina, M. and Mukhamedzhanova, A.

Security Issues of Scientific based Big Data Circulation Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0007843101680173

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications (DATA 2019), pages 168-173

ISBN: 978-989-758-377-3

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

other areas is observed. The rates of increase in Big

Data amount give raise to technological issues

connected with processing methods and the necessary

technical capacities, ethical issues on data types and

their collection methods, and legal issues on data

protection.

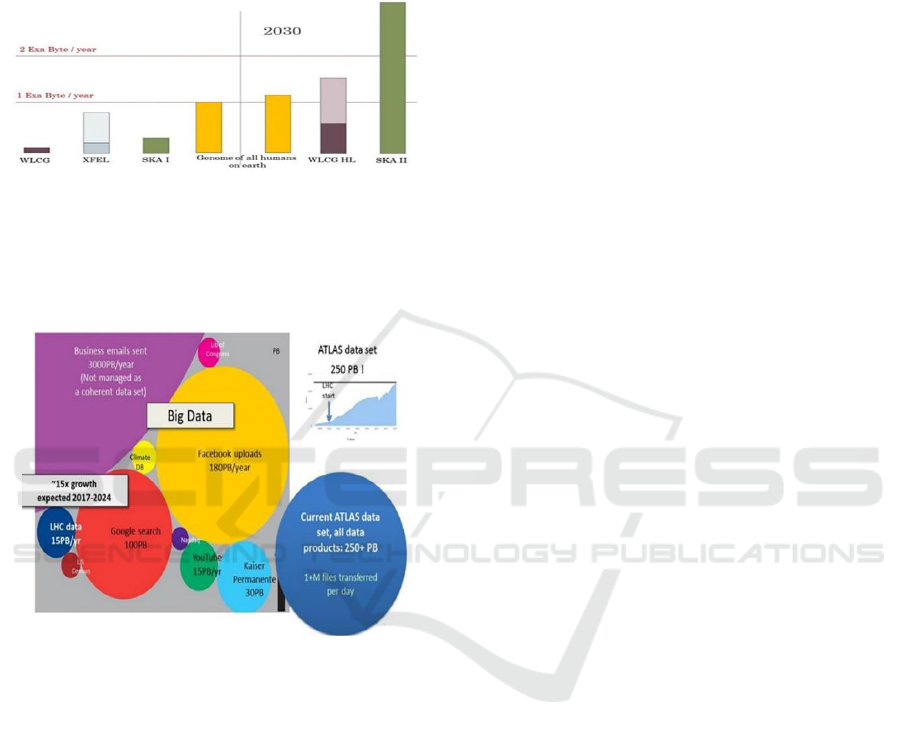

Figure 1: Increase in the amount of data in natural sciences:

the SKA telescope of the 1st and 2nd generations, the XFEL

free-electron laser; the WLCG research at CERN. For

comparison, the amount of information is shown that is

contained in the genome of all living humans on the planet

(Balyakin A. and Mun D., 2017).

Figure 2: Comparative amount of Big Data to date.

Expected growth in scientific data from the Large Hadron

Collider is shown (Balyakin A. and Mun D., 2017).

2 THE CONCEPT AND ESSENCE

OF BIG DATA FROM A LEGAL

STANDPOINT

At the beginning of this paper, we indicated that the

growth of the involvement of Big Data in various

spheres of public life requires, first of all, adequate

legal regulation. In order to build legal regulation, it

is required to determine the object of such regulation,

therefore we consider it important to determine the

concept of “Big Data”.

In fact, Big Data may be defined as a set of data

and information which defies ordering and sorting at

the current stage of human development.

After examining various sources, one can imagine

that currently there is no common understanding and

approach to the definition of Big Data.

At the conclusion of the US Federal Trade

Commission for Big Data: A Tool for Inclusion or

Exclusion? Understanding the Issues (FTC Report)

offers a broader definition “Big Data - arrays of

structured or unstructured data characterized by large

amount, diversity, high change rates, and real-time

processability” (https://www.ftc.gov/reports/big-data

-tool-inclusion-or-exclusion-understanding-issues-

ftc-repor, 2016).

Also one can come across the following definition

in business literature. Big Data refer to a process

offering insight into decision-making. The process is

used by humans and machines for quick analysis of

large amounts of various data (conventional

datasheets and unstructured data such as pictures,

videos, emails, data on transactions and social

networking) from different sources to generate

practical knowledge (Kalyvas and Overly, 2015) .

We approve the position that Big Data are not a

legal term at the moment, but rather describes a

phenomenon with a large variety of implications in

scientific disciplines such as economics, technical

disciplines, legal and social sciences, and likely in

many other areas in the years to come (Fenwick, Kaal

et al, 2016).

It is clear from the above definitions that there is

currently no uniform understanding of Big Data. It is

important to note that there is no single approach to

the essence of Big Data, whether they are a process, a

data set, or a technology.

Such a strong discrepancy in understanding may

give rise to legal uncertainty in the area. To our mind,

the most applicable definition should emphasize the

new qualitative property of data treated as “Big Data”

in comparison with usual data set; thus Big Data are

perceived as a complex of both large amount of data,

and approaches and methods to analyse them. In this

case, Big Data are a process, not an object.

Since Big Data, as mentioned above, are actively

integrated in areas of society’s life in almost all the

world, it seems logical that a single approach to

understanding should be developed. It is also worth

to mention, that there is no widely accepted

vocabulary in such a field. The development of

universal glossary and its implementation should be

the first step in Big Data legal regulations. This issue

can be only solved with joint efforts of scientists, law-

makers, businessmen, etc.

Consider as an example such a property of Big

Data as publicity. Using scientifically-received Big

Data as an example, data can be categorised

Security Issues of Scientific based Big Data Circulation Analysis

169

according to their availability and the importance of

such information can be determined.

First group includes public data, for example data

obtained from SQUARE KILOMETRE ARRAY

facility (https://www.skatelescope.org/technical/

info-sheets/). The publicity of such information

attracts different scientists and contributes to

popularising astronomy.

Second group includes partially available Big

Data, such as published results; data for educational

purposes (so called “abridged” data) available to

authorised users; reconstructed data that become

available after a certain time; “raw” or unprocessed

data that are not made publicly available

(http://opendata.cern.ch/record/413).

And the third group of data are closed data that are

not available to the general public. As a rule, these are

private scientific projects or defence-related research.

The European Free-Electron Laser is an example of

such closed data (https://www.xfel.eu/).

Consider as an example an estimate of the EU

open data market which has a considerable economic

potential. In particular, experts estimate that the total

economic value of such data is expected to increase

from 52 billion euros in 2018 to 75.7 billion euros in

2020 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/

2014-2019/ansip/blog/future-open-data-europe_en).

Having discussed the property of data publicity

and given an example of possible classification of Big

Data, we consider several risks.

The risks of a leak of data, distortion, violation of

secrecy (secrecy of communication, bank secrecy, tax

secrecy, medical secrecy, etc.), sale of data, and human

rights violations seem to be the most important. Thus

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg admitted in 2018 a

leak of the data of 50 million Facebook users

(https://www.newscientist.com/article/2181099-mas

sive-facebook-data-breach-left-50-million-accounts-

exposed/). The data of 25 million Gmail accounts

(email addresses and passwords) were put up for sale

in 2017 (https://www.wsj.com/articles/google-expos

ed-user-data-feared-repercussions-of-disclosing-to-

public-1539017194?mod=hp_lead_pos1).

Another risk is connected with sharing the

responsibility after the decision based on Big Data

analysis was taken. This issue is especially vulnerable

in science and high technology fields where harmful

consequences can be of great scale. Here we need to

point out, that Big Data are a tool to arrive at right

decision, but not the decision itself, it provides one

with new information, but does not give the very

answer.

The above-mentioned challenges require legal

response and support. It is important to note that such

response and support must be uniform throughout the

world, i.e. rely upon universally accepted concepts,

requirements, and approaches. Currently, no single

approach and understanding of the Big Data essence

exists.

3 INSUFFICIENCY OF LEGAL

REGULATION OF BIG DATA IN

MODERN WORLD. GLOBAL

REGULATION PRACTICE

As we discuss aspects of legal regulation and risk

prevention, we first of all think about personal data or

personal information. Though the most laws and rules

are indeed focused on personal information, this is

only one type of data for which business may impose

legal obligations. Currently, business is striving to be

a certain spectrum of confidential information that

requires an adequate level of protection. At the same

time, personal information is mostly exposed to risk.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

(adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10

December 1948) is the fundamental international

treaty in respect of personal information and privacy

(http://www.un.org/ru/universal-declaration-human-

rights/index.html). Article 17 of the Declaration has a

provision under which no one may be subjected to

arbitrary interference with private and family life or

arbitrary infringement on a person’s correspondence;

as well as confirms the right of every person for legal

protection against such interferences.

The principle of protection of privacy saw its

development when the International Covenant on

Civil and Political Rights was adopted (1966)

(http://www.un.org/ru/documents/decl_conv/conven

tions/pactpol.shtml), in its Article 17, which actually

repeated the article of the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights. In its General Comment No 27, the

Human Rights Committee, as it commented on a

provision for a possible limitation of the right for

purposes of public security and protection of public

order, noted that right limitation must serve the

achievement of permitted goals and be necessary for

such protection and as unrestrictive as possible.

Considering the above and the risks outlined in

Section 2 hereof, toughening of the laws on the

personal data protection is the trend of recent years. It

should be noted that this direction of development of

legislation is well-founded.

One of the most widely discussed document in

this area is Regulation (EU) No 2016/679 of the

European Parliament and of the Council of the

DATA 2019 - 8th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

170

European Union on the protection of natural persons

when processing personal data and on the free

movement of such data, which terminates Directive

95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)

(hereinafter referred to as “the GDPR”)

(https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-

protection_en). The main data protection aspects in

the GDPR are: explicit consent of the User; accuracy

of collection purposes; specific time frames; and the

right to be forgotten, destruct and modify data. This

approach is intended to prevent violations.

At the same time, the US Privacy Act 1974

(https://www.justice.gov/opcl/definitions) has a limited

scope of application and concerns aspects of personal

data (US citizens or permanent residents) processing by

federal executive agencies. The strictest requirements

for personal data processing in an electronic

environment among all US regulations have been

established in California where the California Consumer

Privacy Act was adopted in June 2018. It will be

effective since January 1, 2020 (https://leginfo.

legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=2

01720180AB375). Under the general rule, US

legislation does not require explicit consent of the User

and considers that collection notification shall suffice;

the exceptions are medical and geolocation data and

data about persons under 13.

The above regulatory examples represent

different approaches, which in turn may cause legal

uncertainty and regulatory conflicts, so again a

number of technical questions arise about how and

where information should be stored since data is

mainly required to be stored on servers located in the

country of citizenship of the User; ethical questions

about regulatory methods and amounts of data also

arise.

It is suggested that court practice concerning

secrecy of communication should be considered as

part of this problem. The Digital Rights Ireland case

to invalidate Directive 2006/24/EC on the storage of

data generated or processed in connection with the

provision of publicly available electronic

communications services or public communications

networks. The case was brought by the non-

governmental organisation Digital Rights Ireland and

about 12,000 Austrian residents. The Directive was

adopted following a number of terrorist acts in

Madrid and London in 2005. The Directive required

storing data of fixed-line, mobile, and internet

telephony, as well as emails for a period of 6 to 24

months. The regulation was introduced to ensure

availability of data for the period of an investigation,

detection of grave crimes as defined by the law. The

provisions of the Directive were highly debatable,

including the compliance of its provisions with

national constitutions. Disputes led to the ruling of the

Court of Justice of the European Union discussed

herein (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/

TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A62012CC0293). The CJEU

ruled that the Directive led to serious interference

with the rights secured by Articles 7 and 8 of the EU

Charter of Fundamental Rights. Though the CJEU

admitted that such interference met its purpose, it

established that the interference was incommensurate

with the purposes of the Directive. Thus the

interference did not differentiate between

communication facilities, types of data, or types of

users. Besides, no data access procedure and data-

storing time was objectively determined; in

particular, the CJEU considered the time frames

unfounded and unsubstantiated statistically. Besides,

this case explicitly admitted the dangers connected

with the collection of Big Data. For example, as

regards the fact that such collection may provide

accurate details regarding the private life of specific

individuals.

Considering the above, we think that different

approaches to legal regulation of the data protection

may cause imbalance in the legal protection of data

around the world because the degree of regulation is

country dependent. The legal protection of Big Data,

including personal, requires single approach.

3.1 Big Data in Science

The main particular feature of using Big Data in

science is their role in the transformation of society

due to the fact that technologies are now inseparable

from the social, economic and political life. In the

formal language of documents of title it means that,

for instance, in the European Union decision-making

is based on the need for tackling social and

humanitarian challenges in all their manifestations

(Florio et al., 2015). There is a discussion in the EU

with regard to procedures of Big Data management

and regulation; biomedicine (decision-making

artificial intellect) has been chosen as the first field of

application with metadata collection and

development of regulation ethical principles currently

underway.

At the same time, there is a concern voiced in the

EU that the growing recent demands for protection of

personal data may lead to suspension of works with

Big Data. General Data Protection Regulation

(GDPR) (https://gdpr-info.eu/) is cited as an example

of such an obstacle. This policy is followed up by the

recently adopted EU copyright directive. One of the

possible solutions is isolation of the so-called

Security Issues of Scientific based Big Data Circulation Analysis

171

“natural” data (data of natural origin not owned by

anybody) before processing by the Big Data analysis

methods, as proposed by a report of McKinsey

(http://www.tadviser.ru/images/c/c2/Digital-Russia-

report.pdf).

Another problem is storing and accessing Big

Data. The most common proposals include more

spacious data repositories, an advanced search

system, maximum complementarity and connected-

ness of information. With a view to obtaining

maximum results and exercising the equal access

right the EU is actively introducing the open science

principles: thus, the 2016 ROARMAP report

identifies 779 organizational declarations regulating

the open access (https://roarmap.eprints.org/).

In general, Big Data generate an illusion of

knowledge in science, when quantity substitutes

quality. For example, the CISCO report indicates that

the unsorted data are growing at an enormous rate and

according to expert estimates at present up to 90% of

them are useless, since they are overfilled with

information collected for some unknown purposes

(https://www.gartner.com/doc/3100227). Thus, the

main problem of using Big Data is the current lack of

culture of handling this new tool of the scientific and

technological progress. We believe that Big Data

should be viewed as a new instrument of world

cognition that has both positive and negative aspects.

This leads us to a conclusion on the need for

managing the social dimension of high technologies.

4 LEGAL REGULATION OF BIG

DATA IN RUSSIAN

FEDERATION

Within the framework of this study, we suggest a

brief overview of the Russian practice in legal

regulation of Big Data.

The Russian legislation defines Big Data

as a technology, which is explicitly specified in

Directive No 1632-r of the Government

of the Russian Federation, dated 28 July

2017, “On the Approval of the Programme

‘Digital Economy of the Russian Federation’”

(http://pravo.gov.ru/proxy/ips/?docbody=&nd=1024

40918&intelsearch=%D0%E0%F1%EF%EE%F0%

FF%E6%E5%ED%E8%E5+%CF%F0%E0%E2%E

8%F2%E5%EB%FC%F1%F2%E2%E0+%D0%D4

+%EE%F2+28.07.2017+N+1632-%F0).

The General section of the Directive reads that Big

Data are an “end-to-end” technology. At the same

time, this approach seems to be disputable. The

initiative to develop the digital economy is positive.

The inclusion of Big Data in such a programme seems

to be a smart move. Russia proposes that the scientific

potential of the country should concentrate on solving

a number of problems which first of all include risks

to a person and sustainable social development.

Besides, Russian science approaches the

classification of Big Data based on their receiving

method, dividing them into Big User Data and Big

Industrial Data (Saveliyev A., 2018). At the same

time, there is still no legal definition of Big Data in

the Russian Federation. Bill No 571124-7 “On the

Introduction of Amendments to Federal Law ‘On

Information, Information Technology, and on the

Protection of Information’” (http://sozd.duma.gov.

ru/bill/571124-7) is currently under consideration; it

suggests introducing the term “Big User Data”

defined as a set of information from the internet or

other sources about individuals and their behaviour

(without personal data) that does not allow

identifying a specific individual without additional

information or additional processing.

The above definition seems to be more correct in

terms of defining Big Data as a set of information, not

a technology.

Consider as an example the case against

the Gmail heard by the Moscow City Court in

2015 No 33-30344/2015 (https://www.mos-gorsud

.ru/mgs/services/cases/appeal-civil/details/0715f6a5-

4062-4baa-a7c2-45a4c178f4e0). A service user used

Google LLC because he thought that his right of

secrecy of communication had been violated. The

user drew the conclusion based on the context

advertising shown to him which contained elements

corresponding to the contents of the complainant’s

electronic correspondence. In the opinion of Google

LLC, the complainant’s right of secrecy of

communication had not been violated since email

analysis and follow-up advertising was performed by

a robot; Google LLC actually provides no mail

services or posts no advertisements since they are

posted and set up by AdWords users. The Moscow

City Court supported the complainant and held

Google LLC responsible based on the following. The

panel came to the conclusion that the respondent,

Google LLC, in fulfilling its obligations to third

parties under contracts for placing advertisements and

for their effective dissemination as part of the Google

product, monitors, inter alia, email messages and

places said advertisements in the private

correspondence of Google product users in the

Russian Federation based on the results of monitoring

of a specific product user.

Having considered Russian practice in the

regulation of Big Data, the general lack of uniform

DATA 2019 - 8th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications

172

understanding of the Big Data essence may be noted.

At the same time, Russia is agreeing a correct

approach to science and research development, but

the issue of a single approach to Big Data requires

further efforts.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Having considered various methods of legal

regulation of Big Data through the EU, US, and

Russia examples, it is safe to say that different

approaches are used to define the Big Data essence.

To our mind, such a diversified definitions may

jeopardize single approach to regulating Big Data.

Considering that Big Data are actively integrated

in every area of human activity, it is important to

agree on a single approach to understanding Big Data

which could be used as the basis for developing

uniform legal regulation. The development of such an

approach is possible through joint efforts and through

the involvement of international organizations. Since

Big Data have scientific origin, it is important to

make use of the area best practices. The experience of

co-operation on Big Data in the scientific field is

based exactly on co-operation between international

organisations and states, which is determined by

development of “megascience” projects requiring

active international cooperation.

The total amount of Big Data received will soon

put the international community in the face of

technological, ethical, and legal questions which can

be answered by agreeing a single approach to

understanding Big Data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The paper has been financially support by the federal

state-supported institution Russian Foundation for

Basic Research (RFBR), and is a part of scientific

project No. 18-29-16130 MK.

REFERENCES

Balyakin A., Mun D., 2017 Formation of an open science

system in the European Union. Information and

Innovation. No 1. P. 39-44.

Corrales, Marcelo, Fenwick, Mark, Forgó, Nikolaus (Eds.)

(2017). Robotics, AI and the Future of Law. Sweden:

LSpringer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 341.

Digital Rights Ireland Ltd. v. Minister for Communications,

Marine and Natural Resources, Minister for Justice,

Equality and Law Reform, Commissioner of the Garda

Síochána, Ireland, The Attorney General, and Kärntner

Landesregierung, Michael Seitlinger, Christof Tschohl

and others [Electronic resource]: (2014). Judgment of

the Court (Grand Chamber) of April 8, 2014, ECR

[2014] I-238 (Joined Cases C-293 & C-

594/12). Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-

content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A62012CC0293

(2017). Directive No 1632-r of the Government of the

Russian Federation, dated 28 July 2017, “On the

Approval of the Programme ‘Digital Economy of the

Russian Federation’. Available: http://pravo.gov.ru

/proxy/ips/?docbody=&nd=102440918&intelsearch=

%D0%E0%F1%EF%EE%F0%FF%E6%E5%ED%E8

%E5+%CF%F0%E0%E2%E8%F2%E5%EB%FC%F

1%F2%E2%E0+%D0%D4+%EE%F2+28.07.2017+N

+1632-%F0. Last accessed 2019.

Florio, Massimo and Sirtori, Emanuela. (2015). Social

benefits and costs of large scale research

infrastructures. Technological Forecasting and Social

Change. 112. 10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.024.

(2016). FTC Report. Big Data: A Tool for Inclusion or

Exclusion? Understanding the Issues. Available:

https://www.ftc.gov/reports/big-data-tool-inclusion-or-

exclusion-understanding-issues-ftc-repor. Last access-

ed 02/21/2019.

How to Tame the Tech Titans. (2018). Available:

https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21735021-

dominance-google-facebook-andamazon-bad-

consumers-and-competition-how-tame. Last accessed

02/21/2019.

(1996). The International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights. Available: http://www.un.org/ru/documents/

decl_conv/conventions/pactpol.shtml.

James R. Kalyvas Michael R (2014). Overly Big Data A

Business and Legal Guide. Boca Raton: CRC Press

Taylor & Francis Group. 232.

ROARMAP. Available: http://roarmap.eprints.org/.

A.I. Saveliyev. (2018). Options for regulating Big Data and

the protection of privacy in the new economic reality.

Law. (5), 122-144.

Security Issues of Scientific based Big Data Circulation Analysis

173