What Are the Threats?

(Charting the Threat Models of Security Ceremonies)

Diego Sempreboni

1

, Giampaolo Bella

2

, Rosario Giustolisi

3

and Luca Vigan

`

o

1

1

Department of Informatics, King’s College London, U.K.

2

Dipartimento di Informatica, Universit

`

a di Catania, Italy

3

Department of Computer Science, IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark

giamp@dmi.unict.it, rosg@itu.dk

Keywords:

Threat Model, Security Ceremonies, Formal Analysis, Systematic Method.

Abstract:

We address the fundamental question of what are, and how to define, the threat models for a security protocol

and its expected human users, the latter pair forming a heterogeneous system that is typically called a security

ceremony. Our contribution is the systematic definition of an encompassing method to build the full threat

model chart for security ceremonies, from which one can conveniently reify the specific threat models of

interest for the ceremony under consideration. For concreteness, we demonstrate the application of the method

on three ceremonies that have already been considered in the literature: MP-Auth, Opera Mini and the Danish

Mobilpendlerkort ceremony. We discuss how the full threat model chart suggests some interesting threats that

haven’t been investigated although they are well worth of scrutiny. In particular, one of the threat models

in our chart leads to a novel vulnerability of the Danish Mobilpendlerkort ceremony. We discovered the

vulnerability by analysing this threat model using the formal and automated tool Tamarin, which we employed

to demonstrate the relevance of our method, but it is important to highlight that our method is generic and can

be used with any tool for the analysis of security protocols and ceremonies.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Context and Motivation

There is increasing awareness that security protocols

need better attention to their “human element” than

what is traditionally paid. This trend is confirmed by

recent works, both on the formal and on the practical

level.

Examples of recent works at the formal level are

the work by Bella and Coles-Kemp (Bella and Coles-

Kemp, 2012), who defined a layered model of socio-

technical protocols between a user persona and a

computer interface, the work by Martimiano and Mar-

tina (Martimiano and Martina, 2018), who showed

how a popular security ceremony could be made fail-

safe assuming a weaker threat model than normally

considered in formal analysis and compensating for

that with usability, and the work by Basin et al. (Basin

et al., 2016), who provided a formal account on hu-

man error in front of basic authentication properties

and described how to use the Tamarin tool to that end.

However, as we will illustrate in more detail below,

these works cover only a small portion of the land-

scape of possible threat models, so a transformative

approach is called for.

Examples of recent works at the practical level are

the work by Hall (Hall, 2018), who provided real-

world summaries of weak passwords in use, with

2018’s weakest one still being “123456”, and the

work of Bella et al. (Bella et al., 2018), who focussed

on protocols for secure exams and provided a novel

protocol that they have formally analysed using the

tool ProVerif.

Other relevant works exist. Some stress the threats

deriving from humans, for example humans repeat-

ing a previous sequence of actions without consider-

ing whether it would be currently appropriate (Karlof

et al., 2009), or humans making errors during text en-

try (Soukoreff and MacKenzie, 2001). Others discuss

the human behaviour that may be maliciously induced

by a third party, for example by deception (Mitnick

and Simon, 2001) or by following precise coercion

principles (Stajano and Wilson, 2011).

In this paper, we address the underlying, funda-

mental question of

Sempreboni, D., Bella, G., Giustolisi, R. and Viganò, L.

What Are the Threats? (Charting the Threat Models of Security Ceremonies).

DOI: 10.5220/0007924901610172

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE 2019), pages 161-172

ISBN: 978-989-758-378-0

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

161

what are, and how to define, the threat models

for a security protocol and its expected human

users,

the latter pair forming a heterogeneous system that is

typically termed a security ceremony (Ellison, 2007).

While existing works (such as the ones cited

above) define threats that are reasonable, they gener-

ally fail to treat the threats systematically within the

given ceremony, hence potentially missing relevant

combinations of threats. For example, a vulnerability

in a website might be exploited by a specific sequence

of user actions, which an attacking third party would

need to deceive the user to take. This attack cannot

be discussed without admitting a complicated threat

model that combines at the same time (but without

any form of collusion): (i) a bug in the website, (ii) a

user who makes wrong choices and (iii) an active at-

tacker capable of deception.

A huge variety of similar situations may under-

lie modern security ceremonies, and that variety is, in

turn, due to the variety of the ceremonies themselves,

with different levels of intricacies and innumerable

applications, ranging from pre-purchasing a cinema

ticket via the web to obtaining an extended valida-

tion certificate. A remarkable, recent and large-scale,

attack saw the “Norbertvdberg” hacker advertise his

online seed generator iotaseed.io through Google for

a semester; but the generator was bogus, so that Nor-

bertvdberg could hack a number of seeds and harvest

a total of $3.94 million worth of IOTA at the only ex-

tra effort of mounting a DDoS against the IOTA net-

work to prevent investigation. Here, both the hacker

and his website acted maliciously, though arguably in

different ways, mounting a complex socio-technical

attack against both users and the IOTA infrastructure.

Therefore, it is clear that security ceremonies

don’t succumb to the “one threat model to rule them

all” proviso as security protocols traditionally did

with the Dolev-Yao attacker model (Dolev and Yao,

1983). In fact, the Dolev-Yao model has proved to be

very successful for the analysis of security protocols,

where the almighty attacker “rules” over the other

protocol agents who are assumed to behave only as

prescribed by the protocol specification. However, in

the case of security ceremonies such an attacker pro-

vides an inherent “flattening” that likely makes one

miss relevant threat scenarios. By analogy, one could

say that the Dolev-Yao attacker is a powerful ham-

mer... but to a man with a hammer, everything looks

like a nail, forgetting that there are also screws and

nuts and bots (for which a hammer is inadequate).

We advocate that for security ceremonies we need

an approach that provides a birds-eye view, an “over-

view” that allows one to consider what are the differ-

ent threats and where they lie, with the ultimate aim

of finding novel attacks.

1.2 Contributions

The main contribution of this paper is thus

the systematic definition of an encompassing

method to build the full threat model chart for

security ceremonies from which one can con-

veniently reify the threat models of interest for

the ceremony under consideration.

The method starts with a classification of the princi-

pals participating in security ceremonies and contin-

ues with a motivated labelling system for their actions

and principals. Contrarily to some of the mentioned

works, our method abstracts away from the reasons

that determine human actions such as error. It then

continues by systematically combining the principal

labels to derive a number of threat models that, to-

gether, form the full chart of threat models for the

ceremony. We shall see that the higher the number

of principals in a ceremony, the more complicated its

full threat model chart: we shall represent it as a table,

where each line signifies a specific threat model.

For concreteness, we demonstrate the application

of the method on three ceremonies that have already

been considered, albeit at different levels of detail and

analysis, in the literature:

• MP-Auth (Basin et al., 2016; Mannan and van

Oorschot, 2011),

• Opera Mini (Radke et al., 2011)), and

• the Danish Mobilpendlerkort ceremony (Gius-

tolisi, 2017).

We discuss how the full threat model chart suggests

some interesting threats that haven’t been investigated

although they are well worth of scrutiny. In particular,

we find out that the Danish Mobilpendlerkort cere-

mony is vulnerable to the combination of an attack-

ing third party and a malicious phone of the ticket

holder’s. The threat model that leads to this vulner-

ability has not been considered so far and arises here

thanks to our charting method.

To demonstrate the relevance of the chart we mod-

elled and analysed this threat model using the formal

and automated tool Tamarin (Tamarin, 2018), which

enables the unbounded verification of security pro-

tocols, although it is important to highlight that our

method is generic and can be used with any tool for

the analysis of security protocols and ceremonies.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

162

1.3 Organisation

We proceed as follows. In Section 2, we present our

full threat model chart for security ceremonies. In

Section 3 and Section 4, we apply our chart on three

example ceremonies: MP-Auth and Opera-Mini are

discussed in Section 3, whereas we devote the whole

of Section 4 to the Danish Mobilpendlerkort cere-

mony. In Section 5, we take stock and discuss future

work.

2 CHARTING THE THREAT

MODELS OF SECURITY

CEREMONIES

2.1 Principals

The principals that may participate in a security cere-

mony C are

• a number of technical systems,

• a number of humans and

• an attacking third party.

A technical system TechSystem

i

is one that can

be programmed and works by executing its program.

Depending on the architectural level represented in

the given ceremony, a technical system could be ei-

ther a piece of hardware, say a network node, or of

software, say the program executing on that node. We

envisage zero or more technical systems participating

in the ceremony.

A humans principal Human

i

may variously inter-

act with other humans or with the technical systems.

For example, Human

1

may interact directly with

Human

2

in a face-to-face ceremony without technol-

ogy, or with TechSystem

1

and TechSystem

2

, which

may in turn interact between themselves through a se-

curity protocol. As with technical systems, zero or

more humans could participate in the ceremony, and

the case of zero humans would take us back to the

realm of security protocols.

We also consider an attacking third party ATP,

which can be seen as a combination of colluding

attackers, in the style of the Dolev-Yao attacker.

However, the ATP is inherently socio-technical,

namely it is capable of interacting both with a human

by engaging in human actions, and with a technical

system by engaging in digital communication with

it. The ATP could thus be interpreted as the union of

some Human

x

and some TechSystem

y

; the capabilities

of the ATP will become clearer below.

More formally, the principals of a ceremony C can

be formalised as follows:

Technicals(C) := {TechSystem

i

| i = 1, . . . , n}

Humans(C) := {Human

j

| j = 1, . . . , m}

ATP(C) := {ATP

k

| k ≤ 1}

Principals(C) := Technicals(C) ∪

Humans(C) ∪

ATP(C)

where, as is standard, we assume that if n = 0, then C

doesn’t contain any technical system principal. Sim-

ilarly, if m = 0, then C doesn’t contain any human

principal, and if k = 0, then there is no attacking third

party.

2.2 Information and Actions

Principals of a security ceremony exchange informa-

tion of various types, such as a password that a human

may type, a ticket on a smartphone that a human may

show to an inspector, a pdf that a technical system

may display to a human, or a binary message, which

is typically exchanged between technical systems.

More formally, we express the heterogeneity of

the information exchanged in the given ceremony C

by introducing a free type

Information(C).

We don’t need to specify this type in more detail here,

but we take it to cover objects being used and ex-

changed in the ceremony (cards, PDFs, etc.) as well

as data being transmitted (URLs, binary messages,

etc.). Of course, in some cases, Information(C) may

reduce to the standard type of abstract encrypted mes-

sages typically used in security protocol analysis.

A ceremony C comes with a predefined set of

actions to be performed by a principal with another

one, or many more principals, through the exchange

of some information. Actions include the sending of

messages by technical systems, but also commands

that humans may give to technical systems.

The most common sets of technical, human and

attacking third party actions can be defined as ternary

relations A

C,TS

, A

C,H

and A

C,ATP

, respectively:

TechnicalActions(C) :=

A

C,TS

(Technicals, Information, Principals)

HumanActions(C) :=

A

C,H

(Humans, Information, Principals)

ATPActions(C) :=

A

C,ATP

({ATP}, Information, Principals)

Actions can be projected onto given principals

What Are the Threats? (Charting the Threat Models of Security Ceremonies)

163

TechSystem

i

or Human

j

:

TechnicalActions(C)|

TechSystem

i

:=

A

C,TS

({TechSystem

i

}, Information, Principals)

HumanActions(C)|

Human

j

:=

A

C,H

({Human

j

}, Information, Principals)

The relations may, however, also be binary (e.g.,

a principal broadcasting some information to all other

principals, who thus don’t need to be specified as the

third parameter) or quaternary (e.g., a principal send-

ing a message to a principal through another princi-

pal). So, in general, we define the set of actions of

a ceremony as the union of the set of actions of its

principals:

Actions(C) := TechnicalActions(C) ∪

HumanActions(C) ∪

ATPActions(C)

2.3 Action Labels

A key step of our method is the labelling of actions

and the labelling of principals. We introduce the for-

mer in this subsection, and the latter in the next sub-

section.

Each action of a TechSystem

i

of a given ceremony

C can be labelled as follows:

• normal, to indicate actions that are prescribed by

the ceremony, analysing a received message and

generating another one to send out;

• bug, to indicate an unwanted technical deviation

from normal, hence occurring without a specific

goal and normally unexpectedly, such as Heart-

bleed or Shellshock;

• malicious, to indicate a deliberate technical devi-

ation from normal, hence implemented with the

deliberate goal of someone’s profit. Examples of

malicious actions are the execution of malware,

such as a backdoor or a trojan, which the pro-

ducer inserted at production time, in which case

the profit would be the producer’s, or the execu-

tion of post-exploitation code injected by the ATP

while the technical system is in use, in which case

the profit would be the ATP’s.

The second and third labels could be usefully

equipped with parameters carrying out the relevant

details of the bug or of the malicious action. More

formally, for each ceremony, the following function

can be defined:

technical

action label

C

:

TechnicalActions(C) → {normal, bug, malicious}

Each action of a Human

j

of a given ceremony C

can be labelled as follows:

• normal, to indicate actions that are prescribed by

the given ceremony, such as opening a website,

launching an app or handing a paper receipt over

to another human;

• error, to indicate an unwanted human deviation

from normal, hence occurring without a specific

goal and normally unexpectedly, such as typing

a wrong (i.e., different from the one the human

wanted) password, making the wrong choice or

handing out a wrong item;

• choice, to indicate a deliberate human deviation

from normal, hence occurring with the deliberate

goal of someone’s profit. Example choice actions

include those just given as errors, provided that

they are reinterpreted towards profit. Other exam-

ple choices include attempts to attack a technical

system, for example by exploiting a vulnerability.

Profit could be personal for the human making the

choice or it could be ATP’s profit if the human

choice is due to deception.

Also in this case, the second and third labels could

be usefully equipped with parameters carrying out the

relevant details of the error or of the choice. More

formally, for each ceremony, the following function

can be defined:

human action label

C

:

HumanActions(C) → {normal, error, choice}

Finally, the ATP either does nothing (i.e., is not

present at all) or attacks the ceremony. To do the

latter, it may engage in the ceremony by performing

technical actions that are malicious or human actions

of choice:

atp action label

C

:

ATPActions(C) → {malicious, choice}

This is where one can see the difference between

our ATP and the Dolev-Yao attacker. The latter con-

trols the network and can impersonate other princi-

pals by acting honestly in a protocol run (but can-

not break cryptography, yet computational extensions

have been proposed). By contrast, our ATP is an ex-

ternal principal and cannot be an insider of the cere-

mony — the attacks that can happen in that case are

covered in our model by appropriately labelled ac-

tions of the humans or technical systems participat-

ing in the ceremony (in particular, labelled as choice,

error, bug or malicious). Similarly, an attacker that

simply participates honestly in a ceremony can be

expressed by humans and technical systems execut-

ing the ceremony with an “empty” external attacking

third party. Collusion between an insider and an out-

sider can also be modelled that way.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

164

The Dolev-Yao attacker can be captured as a spe-

cial case by appropriately labelling the actions and the

principals of the ceremony, as we shall clarify below.

2.4 Scenario Labels and Principal

Labels

We have just seen how to label each action that the

principals of a given ceremony C may execute. The

labelling system can be lifted at the level of principals.

For example, a principal is labelled as

• normal if the principal is a technical system or a

human and all actions of the principal are labelled

as normal; or as

• choice if the principal is a human and all actions

of the principal are either labelled as choice or as

normal; and so on.

More precisely, we identify 11 relevant groups of ac-

tion labels that a principal, (depending on whether it

is a technical system, a human or the ATP) may use,

and define them as a set of scenarios:

scenario

1

(p) := p ∈ Technicals(C) and

∀a ∈ TechnicalActions(C, p) it is a = normal

scenario

2

(p) := p ∈ Humans(C) and

∀a ∈ HumanActions(C, p) it is a = normal

scenario

3

(p) := p ∈ Technicals(C) and

∀a ∈ TechnicalActions(C, p)

it is a = bug or a = normal

scenario

4

(p) := p ∈ Technicals(C) and

∀a ∈ TechnicalActions(C, p)

it is a = malicious or a = normal

scenario

5

(p) := p = ATP(C) and

∀a ∈ ATPActions(C, p) it is a = malicious

scenario

6

(p) := p ∈ Humans(C) and

∀a ∈ HumanActions(C, p)

it is a = error or a = normal

scenario

7

(p) := p ∈ Humans(C) and

∀a ∈ HumanActions(C, p)

it is a = choice or a = normal

scenario

8

(p) := p = ATP(C) and

∀a ∈ ATPActions(C, p) it is a = choice

scenario

9

(p) := p ∈ Technicals(C) and

∀a ∈ TechnicalActions(C, p)

it is a = bug or a = malicious or a = normal

scenario

10

(p) := p ∈ Humans(C) and

∀a ∈ HumanActions(C, p)

it is a = error or a = choice or a = normal

scenario

11

(p) := p = ATP(C) and

∀a ∈ ATPActions(C, p)

it is a = malicious or a = choice

This list of scenarios emphasises all combinations of

labels that we derive systematically and deem sig-

nificant for the principals, namely bug + malicious

for technical systems, error + choice for humans and

malicious + choice for the attacking third party. The

scenarios show that only technical systems and hu-

mans can take normal actions, while only technical

systems and the attacking third party can take mali-

cious actions, and only humans and the attacking third

party can take choice actions. The scenarios also con-

firm that the attacking third party is the only principal

who can combine both malicious and choice actions.

In order to express the scenarios a principal may

follow, we introduce a function that maps principals

to sets of scenarios, intuitively yielding, for a given

principal, the set of scenarios that the principal may

follow:

scena

C

: Principals(C) → 2

{scenario()

k

|k=1,...,11}

with the obvious constraints that:

• if p ∈ Technicals(C) then scena

C

(p) ∈

2

{scenario

1

(p),scenario

3

(p),scenario

4

(p),scenario

9

(p)}

• if p ∈ Humans(C) then scena

C

(p) ∈

2

{scenario

2

(p),scenario

6

(p),scenario

7

(p),scenario

10

(p)}

• if p = ATP then scena

C

(p) ∈

2

{scenario

5

(p),scenario

8

(p),scenario

11

(p)}

This function is in general total because every princi-

pal will be associated to some scenarios but not sur-

jective; hence, some (sets of) scenarios may not have

any principal that is mapped into them in the given

ceremony C. Intuitively, this means that no principal

acts according to those scenarios in the given cere-

mony. We then introduce the scenario label function:

scenario label

C

: {scenario

k

() | k = 1, . . . , 11} →

{normal, bug, malicious, error, choice,

bug + malicious, error + choice,

malicious + choice}

This function is in general partial, which means that C

may not allow us to define the principal label on some

scenarios, precisely on those that are not associated

to any principal by the function scena

C

. For a given

scenario s, the function is defined as:

scenario

label

C

(s) =

normal if s = scenario

1

() or

s = scenario

2

()

bug if s = scenario

3

()

malicious if s = scenario

4

() or

s = scenario

5

()

error if s = scenario

6

()

choice if s = scenario

7

() or

s = scenario

8

()

bug + malicious if s = scenario

9

()

error + choice if s = scenario

10

()

malicious + choice if s = scenario

11

()

What Are the Threats? (Charting the Threat Models of Security Ceremonies)

165

The labels of a principal can be defined as the la-

bels of the scenarios the principal may follow accord-

ing to function scena

C

(p). More formally:

PLTechnicals

C

(p) :=

{l | l = scenario label

C

(s) for s ∈ scena

C

(p)}

PLHumans

C

(p) :=

{l | l = scenario label

C

(s) for s ∈ scena

C

(p)}

PLATP

C

:=

{l | l = scenario label

C

(s) for s ∈ scena

C

(p)}

Depending on the actions the various principals

may take in C, it is clear from the above definitions

that:

n(PLTechnicals

C

(p)) ≤ 4

n(PLHumans

C

(p)) ≤ 4

n(PLATP

C

) ≤ 3

2.5 Building the Full Threat Model

Chart

The full chart of threat models for a given ceremony

C can be built by systematically combining the labels

of all principals in Principals(C), namely by building

the set PLTechnicals

C

(p) for each technical system

p, the set PLHumans

C

(p) for each human p and the

set PLATP

C

and, finally, by composing their elements

exhaustively. For example, suppose that C features a

human principal and two technical systems that, re-

spectively, use all possible action labels, while no at-

tacking third party is assumed to exist. It means that

we have to build three sets of principal labels:

PLHumans

C

(Human) =

{normal, error, choice, error + choice}

PLTechnicals

C

(TechSystem

1

) =

{normal, bug, malicious, bug + malicious}

PLTechnicals

C

(TechSystem

2

) =

{normal, bug, malicious, bug + malicious}

Due to the cardinality of such sets, the full threat

model chart for C has width n(Principals(C)) = 3 and

depth:

n(PLTechnicals

C

(Human)) ×

n(PLHumans

C

(TechSystem

1

)) ×

n(PLHumans

C

(TechSystem

2

)) = 4

3

= 64.

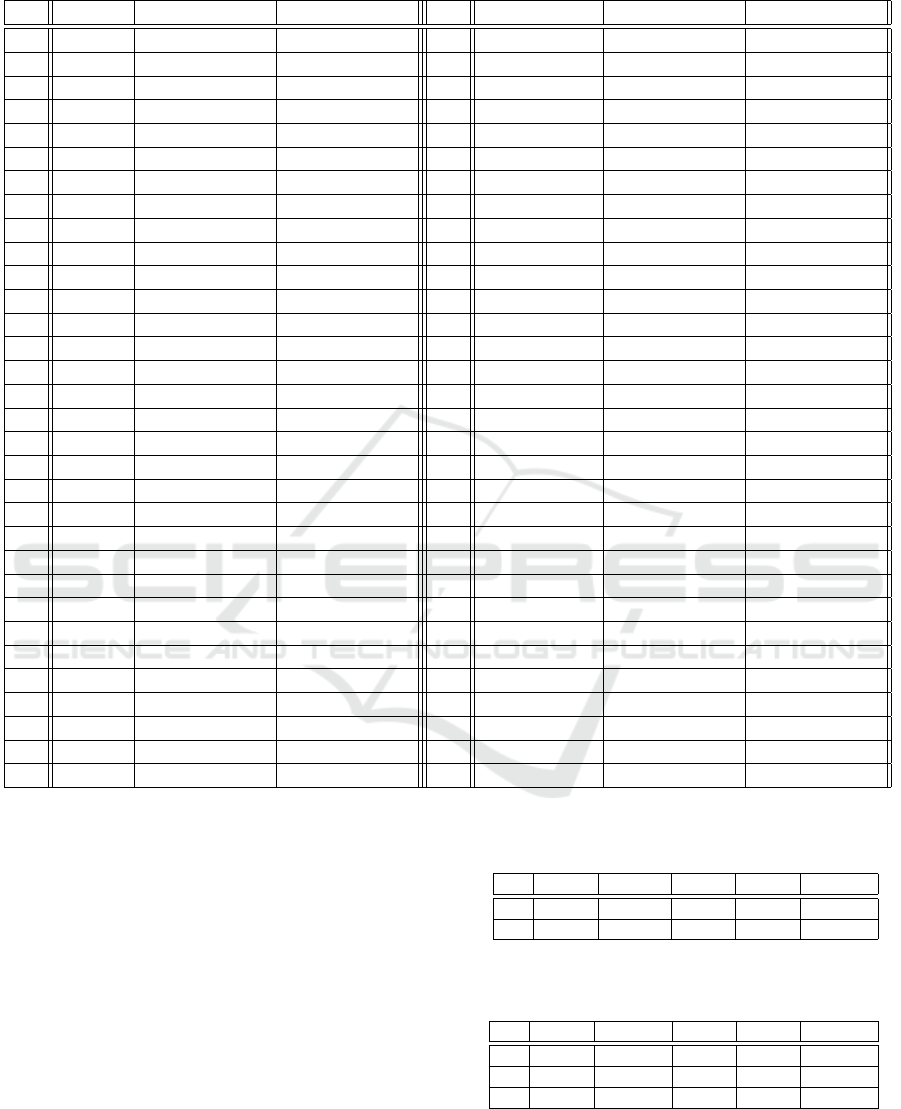

It is given in Table 1.

As another example, consider a ceremony C

0

that

extends C with an attacking third party that only inter-

feres with the human principals in all scenarios, but

not with the technical systems. It means that:

PLATP

C

0

= {choice}.

As a consequence, the full threat model chart for C

0

doubles (the height of) the chart in Table 1, with the

new half being the same as the first half but with an

extra column for the attacking third party repeating

choice for 64 times.

3 USING THE FULL THREAT

MODEL CHART

In this section, we show how our method for the defi-

nition of a full threat model chart can be usefully ap-

plied to existing ceremonies. Depending on the num-

ber of principals and the scenarios they follow, our

aim is to generate a chart in the style of that in Table 1

for each ceremony, and then use the chart to identify

the relevant threat models for the ceremony.

We discuss two example security ceremonies that

have already been analysed to some extent in the liter-

ature: MP-Auth (Basin et al., 2016; Mannan and van

Oorschot, 2011) and Opera Mini (Radke et al., 2011).

Once their respective full threat model chart is avail-

able, it can be used to address which rows, namely

which threat models have already been investigated.

Additionally, the chart can be used to pinpoint other

relevant threat models that we suggest to consider for

further scrutiny of the ceremony, for example by for-

mal analysis.

3.1 MP-Auth

The MP-Auth ceremony (Basin et al., 2016; Mannan

and van Oorschot, 2011) authenticates a human to a

server using the human’s platform and his personal

device, to which the human has exclusive access. The

main idea of the ceremony is that the human never

needs to enter his password on the platform because

this may be controlled by an attacker. The device has

the public key of the server preinstalled. In short,

the ceremony proceeds as follows: the human enters

the name of the server he wants to communicate with

on the platform, which then initiates communication

with the server. The server in turn communicates with

the device through the platform. The device displays

the identity of the server to the human, who checks if

this corresponds to the server he wants to communi-

cate with. If it does, then he enters his password and

identity on the device. Then, the device sends the lo-

gin information to the platform, which relays it to the

server.

According to our method, this ceremony encom-

passes one human principal and three technical sys-

tems. Precisely:

Humans(MP-Auth) := {Human}

Technicals(MP-Auth) :=

{Platform, Device, Server}

We also allow for an attacking third party, so that the

resulting principals are:

Principals(MP-Auth) := Humans(MP-Auth) ∪

Technicals(MP-Auth) ∪

ATP(MP-Auth)

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

166

Table 1: The full threat model chart for a ceremony with a human principal, two technical systems and no attacking third

party.

# Human TechSystem

1

TechSystem

2

# Human TechSystem

1

TechSystem

2

1 normal normal normal 33 choice normal normal

2 normal normal bug 34 choice normal bug

3 normal normal malicious 35 choice normal malicious

4 normal normal bug+malicious 36 choice normal bug+malicious

5 normal bug normal 37 choice bug normal

6 normal bug bug 38 choice bug bug

7 normal bug malicious 39 choice bug malicious

8 normal bug bug+malicious 40 choice bug bug+malicious

9 normal malicious normal 41 choice malicious normal

10 normal malicious bug 42 choice malicious bug

11 normal malicious malicious 43 choice malicious malicious

12 normal malicious bug+malicious 44 choice malicious bug+malicious

13 normal bug+malicious normal 45 choice bug+malicious normal

14 normal bug+malicious bug 46 choice bug+malicious bug

15 normal bug+malicious malicious 47 choice bug+malicious malicious

16 normal bug+malicious bug+malicious 48 choice bug+malicious bug+malicious

17 error normal normal 49 error+choice normal normal

18 error normal bug 50 error+choice normal bug

19 error normal malicious 51 error+choice normal malicious

20 error normal bug+malicious 52 error+choice normal bug+malicious

21 error bug normal 53 error+choice bug normal

22 error bug bug 54 error+choice bug bug

23 error bug malicious 55 error+choice bug malicious

24 error bug bug+malicious 56 error+choice bug bug+malicious

25 error malicious normal 57 error+choice malicious normal

26 error malicious bug 58 error+choice malicious bug

27 error malicious malicious 59 error+choice malicious malicious

28 error malicious bug+malicious 60 error+choice malicious bug+malicious

29 error bug+malicious normal 61 error+choice bug+malicious normal

30 error bug+malicious bug 62 error+choice bug+malicious bug

31 error bug+malicious malicious 63 error+choice bug+malicious malicious

32 error bug+malicious bug+malicious 64 error+choice bug+malicious bug+malicious

The most general case in which every principal gets

all possible labels sees:

n(PLHumans

MP-Auth

(Human)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

MP-Auth

(Platform)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

MP-Auth

(Device)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

MP-Auth

(Server)) = 4

n(PLATP

MP-Auth

) = 2

Hence, the full threat model chart has 4

4

· 2

1

= 512

lines. The threat models considered in previous

work (Basin et al., 2016) can be reinterpreted in our

chart as shown in Table 2.

However, our chart also highlights at least three

more relevant threat models that haven’t been consid-

ered yet. These are summarised in Table 3.

Threat model (c) considers a human that makes er-

rors while interacting with a buggy platform under the

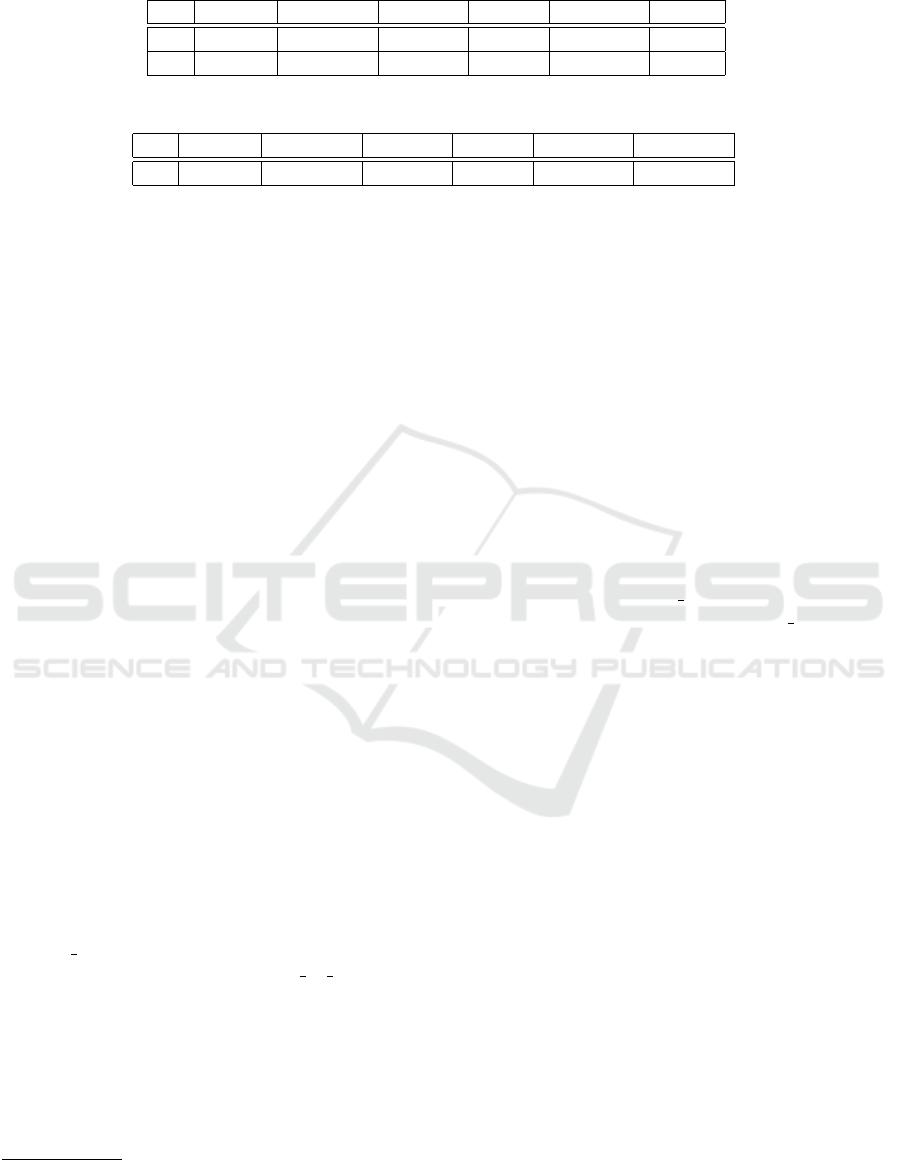

Table 2: The two threat models already considered for the

MP-Auth ceremony.

Human Platform Device Server ATP

(a) error normal normal normal malicious

(b) choice normal normal normal malicious

Table 3: Additional threat models relevant for the MP-Auth

ceremony.

Human Platform Device Server ATP

(c) error bug normal normal malicious

(d) error normal bug normal malicious

(e) choice malicious normal normal malicious

attack of an ATP; (d) considers the interaction with a

buggy device; (e) considers a malicious platform and

a malicious ATP as well as a human agent who de-

What Are the Threats? (Charting the Threat Models of Security Ceremonies)

167

cides to misbehave. It is clear that our chart helped

distill out relevant threat models that have been ne-

glected so far, and that a formal analysis is required

to detect potential vulnerabilities entailed by the new

threat models. In fact, differently from (a) and (b) in

Table 2, the new cases in Table 3 add potential weak

points that might lead to new attacks.

3.2 Opera Mini

The Opera Mini ceremony (Radke et al., 2011) be-

gins with the user of a smartphone typing the ad-

dress of his bank’s website into the Opera Mini web

browser. HTTPS connections are opened between the

smartphone and Opera’s Server, and between Opera’s

server and the bank’s server. The request for the

page is then passed through to the bank, which replies

with its customer login page. The Opera server ren-

ders this page and sends the compressed output to

the user’s smartphone device. On the smartphone,

Opera Mini then displays the webpage, including the

padlock symbol. The user sees the padlock symbol

and, if he chooses to input his login information and

password, then this is sent back to the bank’s server

via the Opera encrypted channel, decrypted at the

Opera Server, and then re-encrypted and sent on to

the bank’s server via the HTTPS channel.

We don’t allow for an attacking third party here,

so, according to our method, the principals of the cer-

emony are:

Humans(Opera-Mini) := {Human}

Technicals(Opera-Mini) :=

{Device, Opera-Server, Bank-Server}

Principals(Opera-Mini) :=

Humans(Opera-Mini) ∪ Technicals(Opera-Mini)

The most general case in which every principal gets

all possible labels sees:

n(PLHumans

Opera-Mini

(Human)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

Opera-Mini

(Device)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

Opera-Mini

(Opera-Server)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

Opera-Mini

(Bank-Server)) = 4

Hence, the full threat model chart has 4

4

= 256 lines.

The only threat model considered in (Radke et al.,

2011) can be reinterpreted in our chart as shown in

Table 4.

Table 4: The threat model already considered for the Opera

Mini ceremony.

Human Device Opera-Server Bank-Server

(a) normal bug normal normal

However, our chart also highlights at least three

more relevant threat models that haven’t been consid-

ered yet. These are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5: Additional threat models for the Opera Mini cere-

mony.

Human Device Opera-Server Bank-Server

(b) error normal normal normal

(c) error normal normal malicious

(d) choice normal normal normal

The threat model (a) analysed in (Radke et al.,

2011) considers just a buggy platform. We believe

that it would be interesting to consider also threat

model (b), where the human simply makes errors us-

ing the Opera Mini browser possibly, threat model

(c), under the presence of a malicious Bank-Server.

Threat model (d), instead, presumes that the 3 techni-

cal systems don’t deviate from their specification but

the human deliberately does in order to seek an ad-

vantage.

4 THE DANISH

MOBILPENDLERKORT

As a more detailed example, let us consider the in-

spection ceremony for the mobile transport ticket in

Denmark, which is known to have two vulnerabili-

ties (Giustolisi, 2017). It involves five principals, two

of which are human beings (ticket holder and ticket

inspector). Despite the combinatorial explosion due

to the number of principals and actions, it is inter-

esting to dissect some combinations, especially those

in which both human principals deviate from the pre-

scribed ceremony.

4.1 Description

As a precondition, the human downloads on his

phone a specific app, called Mobilpendlerkort, which

allows the human to buy a ticket using a credit card.

The human gives the phone his personal details and

travelling preferences, which the phone then forwards

to the train company’s server. This server sends back

to the phone a QR code that encodes a signed version

of the human’s travelling preferences. Upon request

of the ticket inspector, the human shows the phone

with the QR code, and the inspector visually checks

the authenticity of the ticket. Then, the inspector

checks the validity of the barcode via a ticket scanner,

which has access to the verification key needed

to validate the signature on the QR code. Finally,

the scanner emits a green light if the verification

succeeds, a red light otherwise. Additionally, the

inspector may ask the human to show a valid ID

document to check the human’s identity.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

168

We identify the following principals in the cere-

mony (where, for simplicity, we have considered the

phone and the ticketing app as a single technical sys-

tem):

Humans(Danish-Mobil) := {Human, Inspector}

Technicals(Danish-Mobil) :=

{Phone, Scanner, Server}

Principals(Danish-Mobil) :=

Humans(Danish-Mobil) ∪

Technicals(Danish-Mobil) ∪

ATP(Danish-Mobil)

The most general case with legitimate principals get-

ting all possible labels sees:

n(PLHumans

Danish-Mobil

(Human)) = 4

n(PLHumans

Danish-Mobil

(Inspector)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

Danish-Mobil

(Phone)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

Danish-Mobil

(Scanner)) = 4

n(PLTechnicals

Danish-Mobil

(Server)) = 4

We also assume the attacking third party to only mis-

behave as formalised by its two labels, therefore:

n(PLATP

Danish-Mobil

) = 2

Hence, the full threat model chart has 4

5

· 2

1

= 2048

lines.

4.2 Threat Models

We focus on three threat models derived from our

chart. The threat models (a) and (b) in Table 6 have

been considered in (Giustolisi, 2017) and shown to

lead to vulnerabilities. The additional threat model

(c) in Table 7 provides new insights about a potential

yet realistic attack to the ceremony.

More in detail, threat model (a) considers a human

who chooses to forge the screen of the app that dis-

plays the ticket details. The human chooses not to use

the original app, but installs a fake app on his phone

so as to mimic both watermark and background of the

original app. This threat model sees the inspector only

choose to visually check the ticket details and not to

scan the signed QR code. This is routine in Metro or

local trains (Giustolisi, 2017). This vulnerability no-

tably doesn’t require an attacking third party because

the human takes advance of an inspector who chooses

to deviate from the ceremony.

Threat model (b) differs from the previous one as

the inspector doesn’t deviate from the protocol and

there is an attacking third party. The latter plays the

role of a ticket holder who buys a valid ticket but

then chooses to send the signed QR code to the hu-

man. Then, the human uses a fake app as in (a) to

mimic watermark and background of the original app

and display the QR code sent by the attacking third

party. Notably, both the scanner and the inspector fol-

low the ceremony. This vulnerability, hence, enables

a ticket holder to buy a valid ticket that can be shared

with other people to travel for free. More specifically,

the attack is possible because the QR code doesn’t in-

clude the personal details of the ticket holder. Thus,

a valid QR code can be reused by different people.

The attacking third party is essential to signify the

attack and provides a way to reason about collusion

among different principals in a quite abstract and gen-

eral manner.

Threat model (c) has all principals except the

phone behave as normal and also features an attack-

ing third party active towards the phone, hence be-

having as malicious. This threat model represents a

form of collusion of the attacking third party with the

human’s phone, for example with the phone running

some malware on behalf of the attacking party. As a

consequence, the phone is enabled to steal a valid QR

code from a ticket bought by the human and send it

back to the attacking party, who, in turn, can redis-

tribute tickets to colluding phones.

Threat model (c) has not been considered so far

and arises here thanks to our charting method. To

demonstrate the relevance of the chart we analysed

threat model (c) using the formal and automated tool

Tamarin, which enables the unbounded verification of

security protocols, although it is important to high-

light that our method can be used with any tool for

the analysis of security protocols and ceremonies.

4.3 Formal Analysis

Tamarin (Tamarin, 2018) allows one to analyse reach-

ability and equivalence-based properties in a sym-

bolic attacker model. We chose Tamarin mainly be-

cause of its expressive input language based on mul-

tiset rewriting rules. It can be used to easily specify

customary threat models derived from our chart.

A Tamarin rule has a premise and a conclusion and

operates on a multiset of facts. Facts are predicates

that store state information. Executing a rule means

that all facts in the premise are present in the current

state and are consumed in favour of the facts in the

conclusion. Tamarin supports linear facts, which may

be consumed by rules only once, and persistent facts,

which may be consumed by rules arbitrarily often.

A fundamental choice is to exclude Tamarin’s

built-in attacker model (i.e., the Dolev-Yao attacker)

in favour of the threats provided by the line in our

chart model. More specifically, the communication

among principals is modelled by non-persistent pri-

vate channel rules. Human, Scanner, Server, and In-

What Are the Threats? (Charting the Threat Models of Security Ceremonies)

169

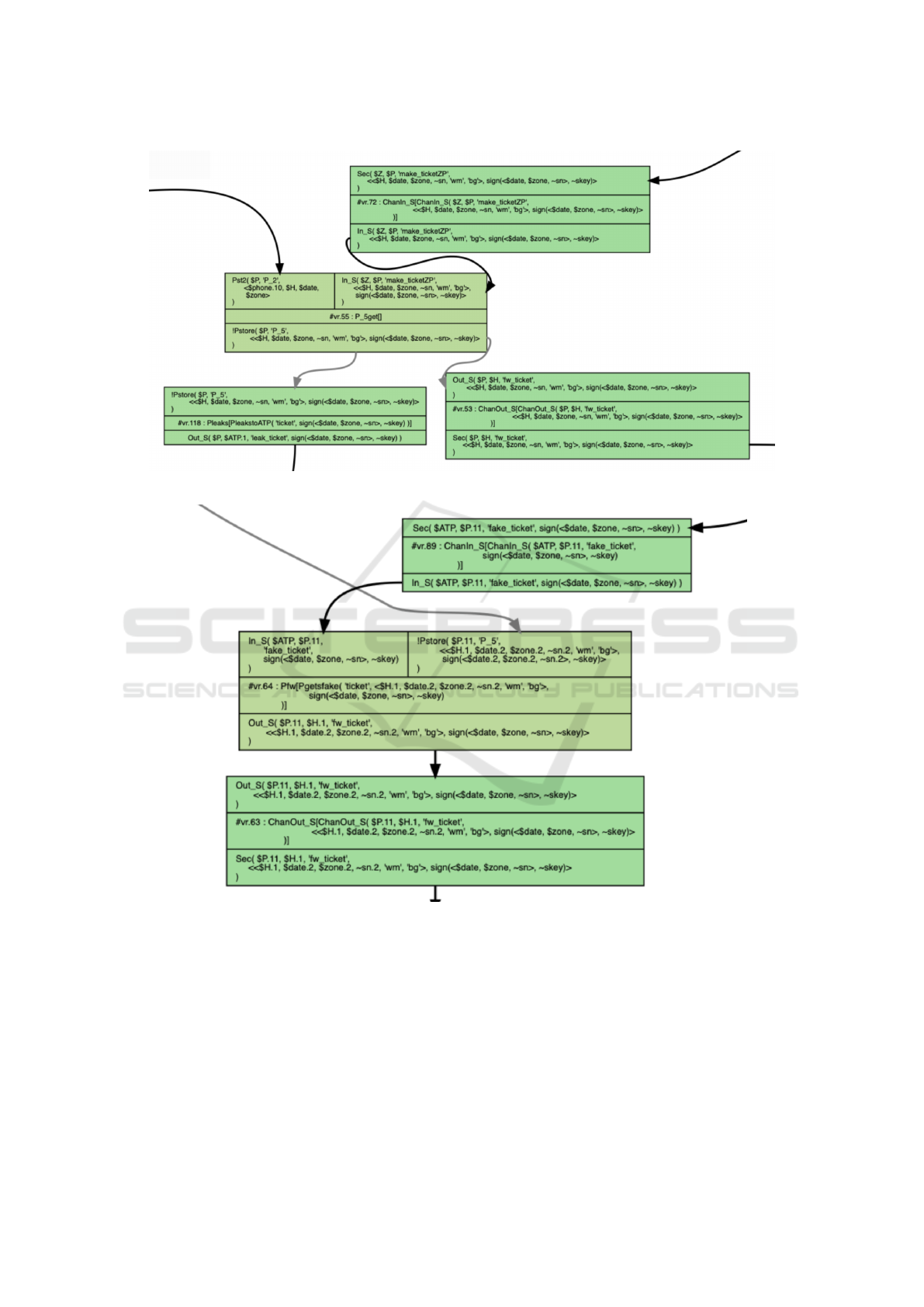

Table 6: The two threat models already considered for the Danish-Mobil ceremony.

Human Phone Scanner Server Inspector ATP

(a) choice malicious normal normal choice —

(b) choice malicious normal normal normal choice

Table 7: An additional threat model relevant for the Danish-Mobil ceremony.

Human Phone Scanner Server Inspector ATP

(c) normal malicious normal normal normal malicious

spector are labelled as normal, hence their Tamarin

specifications are the ones prescribed by the cere-

mony. Phone and ATP are labelled as malicious,

hence they have deviating behaviours which are cap-

tured by the Tamarin rules below.

1

Due to space limi-

tations, we assume basic familiarity of the reader with

Tamarin and only discuss the main facts and rules.

rule Pleaks:

[!Pstore($P,’P_5’,<s1, signed_qr>)]

--[PleakstoATP(’ticket’,signed_qr)]->

[Out_S($P, $ATP,’leak_ticket’,signed_qr)]

rule Pfw:

[In_S($ATP,$P,’fake_ticket’,signed_qr_atp),

!Pstore($P,’P_5’,<s1, signed_qr>)]

--[Pgetsfake(’ticket’,s1,signed_qr_atp)]->

[Out_S($P, $H,’fw_ticket’,<s1,signed_qr_atp>)]

rule ATPgets:

[In_S($P,$ATP,’leak_ticket’,signed_qr)]

--[ATPKnow($P,signed_qr)]->

[!ATPK($P,signed_qr)]

rule ATPsends:

[!ATPK($P,signed_qr)]

-->

[Out_S($ATP, $PP,’fake_ticket’,signed_qr)]

The fact !Pstore formalises a phone storing the

ticket purchased by the traveller, while the fact !ATPK

expresses the knowledge of the ATP, and is con-

veniently instantiated to a signed QR code. Rules

Pleaks and Pfw model behaviours of a malicious

phone that respectively leaks a signed QR code

(signed qr) to the ATP and forwards another signed

QR code sent by the ATP (signed qr atp) to the

human. Rules ATPgets and ATPsends model be-

haviours of a malicious ATP that respectively receives

a signed QR code from a malicious phone and for-

wards it to a different malicious phone. We argue that

these rules reflect very basic malicious behaviours for

phone and ATP.

We check one of the main security properties for

1

The full Tamarin code is available for review

at the anonymous link https://www.dropbox.com/s/

o93hq0bh75lpxqk/mobilpendlerkort.spthy?dl=0.

a ticketing ceremony, namely, that two different hu-

man beings cannot ride with the same ticket. This is

formalised in Tamarin by the following lemma:

lemma oneticketpertraveller:

"All h1 h2 s #i #j. OK(h1,s)@i &

OK(h2,s)@j & i<j ==> h1=h2"

The label OK(h,s) expresses a successful verifica-

tion of a ticket with serial number s and ticket holder

h by a ticket inspector. Thus, the property says that

two distinct verifications of a ticket with the same se-

rial number should concern the same ticket holder.

Tamarin finds an attack that violates the stated

property and provides a graph that details the steps

of the attack. We focus on two crucial steps.

The first step is outlined in Figure 1, in which

the conclusion of rule P 5get is consumed by the

premises of rules Pleaks and ChanOut S, thus creat-

ing two branches. The former rule leaks the signed

QR code to the ATP, while the latter forwards the

ticket to the human, who notably doesn’t detect that

something bad is happening.

The other crucial step is outlined in Figure 2,

which depicts a portion of what follows in the branch

due to the rule Pleaks. One of the premises of the

rule Pfw is satisfied by a signed QR code that was

purchased by another traveller but is rerouted by the

ATP through the malicious phones. The other premise

is satisfied by the fact !Pstore, which stores the cor-

rect ticket details of the current traveller. The mali-

cious phone combines the correct ticket details with

the signed QR code forwarded by the ATP, and for-

wards the resulting fake ticket to the human. Later,

during ticket inspection, the fake ticket is successfully

verified.

Although the attack mechanism is similar to the

one described in the previous threat model, the at-

tacking party doesn’t need to create a fake ticket but

just to redistribute the signed QR code from one ma-

licious phone to another. The consequences on the

ticket holder are more serious in this case. The holder

is unaware that his ticket is being reused by someone

else. However, post-analysis techniques may reveal a

misuse of fake tickets, hence suggest a software up-

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

170

Figure 1: A snapshot of a portion of the attack graph provided by Tamarin. The phone leaks part of the ticket to the ATP.

Figure 2: A snapshot of a portion of the attack graph provided by Tamarin. The phone combines the details of the correct

ticket with the signed QR code provided by the ATP.

date to the scanner so that the scanner would inval-

idate the fake ticket (further legal action against the

ticket holder could follow).

It is clear that the full threat model chart allows us

to appreciate how the same overarching attack mech-

anism may be used in different scenarios according to

the selected threat model. As we have seen, different

consequences may arise, thus bringing novel insights

to a focus.

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS

The method that we proposed allows one to build the

chart of all threat models for a given security cere-

mony upon the basis of the relevant principals (thus

identifying the columns of the table) and their capa-

bilities (thus identifying the rows of the table). The

security analyst can then relate the threat models that

have already been considered, if any, to those that

What Are the Threats? (Charting the Threat Models of Security Ceremonies)

171

haven’t and, in every case, address all possible threat

models of interest pragmatically.

We believe that our formalisation of the ceremony

principals based on their actions provides a seman-

tics that is, in some sense, more operational than the

one that is traditionally considered for security proto-

cols. For example, notions such as impersonation and

collusion are neatly represented through our approach

by endowing principals with appropriate functioning

or behaviour. Still, we are aware that the notions that

we have introduced in this paper are quite coarse and

in need of a more fine-grained formalisation.

The research ahead of us is clearly defined: how to

cope with the size and complexities of the full threat

model chart. One approach could be the description

of appropriate measures and weights to prioritise the

different threat models so as to create an ordered list.

The given ceremony could then be verified, in turn,

against each item of the list.

Another approach could be the definition of meth-

ods to handle the full threat model chart in one go,

perhaps parameterising the findings upon the threat

model. We have demonstrated that Tamarin can be

customised to dealing with a specific threat model ex-

tracted from the chart, hence disposing with the tra-

ditional Dolev-Yao attacker model; however, it is not

yet clear whether and how Tamarin could scale up to

the challenges identified here. We are aware that these

challenges stretch out the requirements traditionally

put on tool support, because the formal analysis will

have to identify not only an attack but also the threat

models that substantiate it.

With humans increasingly immersed in a plethora

of security ceremonies, this research promises consid-

erable impact on both modern technologies and mod-

ern society.

REFERENCES

Basin, D. A., Radomirovic, S., and Schmid, L. (2016).

Modeling Human Errors in Security Protocols. In

Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF),

pages 325–340. IEEE CS Press.

Bella, G. and Coles-Kemp, L. (2012). Layered analysis of

security ceremonies. In 27th IFIP TC 11 Informa-

tion Security and Privacy Conference, pages 273–286.

Springer.

Bella, G., R.Giustolisi, and G.Lenzini (2018). In-

valid Certificates in Modern Browsers: A Socio-

Technical Analysis. IOS Journal of Computer Secu-

rity, 26(4):509–541.

Dolev, D. and Yao, A. (1983). On the security of public key

protocols. IEEE Transactions on information theory,

(2):198–208.

Ellison, C. M. (2007). Ceremony design and analysis. IACR

Cryptology ePrint Archive, page 399.

Giustolisi, R. (2017). Free Rides in Denmark: Lessons from

Improperly Generated Mobile Transport Tickets. In

NordSec, LNCS 10674, pages 159–174. Springer.

Hall, J. (2018). SplashData’s Top 100 Worst Passwords of

2018. https://www.teamsid.com/splashdatas-top-100-

worst-passwords-of-2018/.

Karlof, C., Tygar, J. D., and Wagner, D. (2009).

Conditioned-safe Ceremonies and a User Study of an

Application to Web Authentication. In SOUPS. ACM

Press.

Mannan, M. and van Oorschot, P. C. (2011). Leveraging

personal devices for stronger password authentication

from untrusted computers. Journal of Computer Se-

curity, (4):703–750.

Martimiano, T. and Martina, J. E. (2018). Daemones Non

Operantur Nisi Per Artem (Daemons Do Not Operate

Save Through Trickery: Human Tailored Threat Mod-

els for Formal Verification of Fail-Safe Security Cer-

emonies). In Security Protocols 2018, LNCS 11286,

pages 96–105. Springer.

Mitnick, K. D. and Simon, W. L. (2001). The Art of De-

ception: Controlling the Human Element of Security.

John Wiley & Sons.

Radke, K., Boyd, C., Nieto, J. M. G., and Brereton, M.

(2011). Ceremony Analysis: Strengths and Weak-

nesses. In 26th IFIP SEC, pages 104–115. Springer.

Soukoreff, R. W. and MacKenzie, I. S. (2001). Measur-

ing Errors in Text Entry Tasks: An Application of the

Levenshtein String Distance Statistic. In Extended Ab-

stracts of CHI, pages 319–320. ACM Press.

Stajano, F. and Wilson, P. (2011). Understanding scam vic-

tims: seven principles for systems security. Commun.

ACM, (3):70–75.

Tamarin (2018). The Tamarin User Manual. https://tamarin-

prover.github.io.

SECRYPT 2019 - 16th International Conference on Security and Cryptography

172