Putting the “Account” into Cloud Accountability

Martin Gilje Jaatun

1,2 a

and Siani Pearson

3 b

1

Department of Software Engineering, Safety and Security, SINTEF Digital, Trondheim, Norway

2

University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

3

Malvern, U.K.

Keywords:

Cloud Computing, Accountability, Security, Privacy, GDPR.

Abstract:

Security concerns are often cited as the most prominent reason for not using cloud computing, but customers of

cloud users, especially end-users, frequently do not understand the need to control access to personal informa-

tion. On the other hand, some users might understand the risk, and yet have inadequate means to address it. In

order to make the Cloud a viable alternative for all, accountability of the service providers is key, and with the

advent of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), ignoring accountability is something providers

in the EU market will do at their peril. To be able to hold cloud service providers accountable for how they

manage personal, sensitive and confidential information, there is a need for mechanisms that can mitigate risk,

identify emerging risks, monitor policy violations, manage any incidents, and provide redress. We believe that

being able to offer accountability as part of the service provision will represent a competitive edge for service

providers catering to discerning cloud customers, also outside the GDPR sphere of influence. This paper will

outline the fundamentals of accountability, and provide more details on what the actual “account” is all about.

1 INTRODUCTION

Security concerns are often cited as the most promi-

nent reason for not using cloud computing (CIPL,

2009; Rong et al., 2013). At the same time, customers

of cloud users, especially end-users, frequently do not

understand the need to control access to personal in-

formation. This is particularly evident in the con-

text of social media, where the users are not the cus-

tomers, but the product (being sold to marketers). On

the other hand, some users might understand the risk,

and yet have inadequate means to address it (Cattaneo

et al., 2012). In order to make the Cloud a viable alter-

native for all, accountability of the service providers

is key.

To be able to hold cloud service providers ac-

countable for how they manage personal, sensitive

and confidential information, there is a need for an or-

chestrated set of mechanisms: preventive (mitigating

risk), detective (monitoring and identifying risk and

policy violation), and corrective (managing incidents

and providing redress) (Jaatun et al., 2016).

Suppliers within the cloud eco-system need to be

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7127-6694

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3576-9402

able to differentiate themselves in what ultimately is

a commodity market, and being able to offer account-

ability as part of the service provision will represent

a competitive edge for service providers catering to

discerning cloud customers (Pr

¨

ufer, 2013).

2 ACCOUNTABILITY

In order to provide accountability (Pearson, 2017),

providers must facilitate choice for users, and exer-

cise control over handling of data. Such data practices

must be transparent to the users, and the providers

must also be compliant with applicable laws and reg-

ulations.

2.1 Requirements

The starting point is that an accountable organization

must commit to responsible stewardship of other peo-

ple’s data, requiring that it:

• defines what it does,

• monitors how it acts,

• remedies any discrepancies between the former

two,

Jaatun, M. and Pearson, S.

Putting the "Account” into Cloud Accountability.

DOI: 10.5220/0008346000090018

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science (CLOSER 2019), pages 9-18

ISBN: 978-989-758-365-0

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

9

• explains and justifies any action.

These elements can be elaborated as follows.

1. An accountable organization must demonstrate

willingness and capacity to be responsible and an-

swerable for its data practices.

2. An accountable organization must define policies

regarding their data practices.

3. An accountable organization must monitor its data

practices.

4. An accountable organization must correct policy

violations.

5. An accountable organization must demonstrate

policy compliance.

In addition to the above, there is a need for ac-

countability across the cloud service provision and

governance chains, and not just in isolation for organi-

zational cloud consumers or cloud service providers.

Hence there is a need for provision of evidence of sat-

isfaction of obligations right along the service pro-

vision chain, as well as aspects such as checking

that partners are accountable too and that there has

been proper allocation of responsibilities along the

service provision chain. These requirements need to

be reflected within the processes for organizations de-

scribed above, but in addition there are implications in

terms of the way that the accountability governance

chains will operate, the scope of risk assessment and

the ways in which other stakeholders are able to hold

this organization to account. In complex, dynamic or

global situations there needs to be a practical solution

for data subjects to obtain both requisite information

about the service provision and remediation.

Attributter

Praksiser

Mekanismer

Organisational

Operational

abstract

concrete

Conceptual

Mechanisms

Practices

Attributes

Figure 1: A Conceptual Framework for Accountability.

2.2 Conceptual Model

Our conceptual accountability model (see Figure 1)

elaborates on our definition accountability (Jaatun

et al., 2016) by means of a set of

• Accountability Attributes: conceptual elements

of accountability applicable across different do-

mains

• Accountability Practices: emergent behavior

characterizing accountable organizations (that is,

how organizations operationalize accountability

or put accountability into practices)

• Accountability Mechanisms: diverse processes,

non-technical mechanisms and tools that support

accountability practices.

The core attributes of our accountability model

are:

Transparency: the property of a system, organiza-

tion or individual of providing visibility of its gov-

erning norms, behavior and compliance of behav-

ior to the norms.

Responsiveness: the property of a system, organiza-

tion or individual to take into account input from

external stakeholders and respond to queries of

these stakeholders.

Remediability: the property of a system, organiza-

tion or individual to take corrective action and/or

provide a remedy for any party harmed in case of

failure to comply with its governing norms

Responsibility: the property of an organization or in-

dividual in relation to an object, process or system

of being assigned to take action to be in compli-

ance with the norms

Verifiability: the extent to which it is possible to as-

sess norm compliance (i.e. a property of a system,

service or process that its behavior can be checked

against norms)

Appropriateness: the extent to which the technical

and organizational measures used have the capa-

bility of contributing to accountability.

Effectiveness: the extent to which the technical and

organizational measures used actually contribute

to accountability.

To support and implement the main accountabil-

ity attributes, we have developed a ’toolkit’ (Jaatun

et al., 2016) that forms the bottom layer in Figure 1

and from which organizations can select as appropri-

ate.

3 THE ACCOUNT

Provision of accounts (Gittler et al., 2016) is an im-

portant part of the organisational lifecycle, and the

means of demonstrating accountability. The form

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

10

and content of accounts are contextually dependent.

In this section the varying properties of accounts are

considered.

3.1 What is an Account?

An account is a report or description that may be writ-

ten and/or oral, of an event or process. It serves to

report what happened, what has happened, or what

might happen. An account generally contains answers

to the ‘reporters’ questions”, i.e. who, what, where,

when and why. It may also include measures taken to

remedy prior failures. An account of the same event

or process might be provided several times and vary

in its format and information depending on the recip-

ient.

An example where accounts are needed is data

breach notification. In this case, the following infor-

mation should be provided:

• To explain who committed the breach (or if un-

known, how investigation to discover perpetrator)

• What the breach consisted of

• When the breach occurred (and was discovered if

different dates)

• How and why it occurred, extent of breach

• What measures are being taken to prevent any fur-

ther such breaches in future

• Contact information for a department or person to

respond to further questions (and maybe link to

web page for updates)

3.2 Forms of Account

There are two main forms of account: proactive or

retrospective accounts.

Proactive accounts relate to reports before mak-

ing services available. Provision of an account could

be proactive, in the sense that the choice of account-

ability mechanisms and tools needs to be justified to

external parties, and this could happen before any pro-

cessing takes place (perhaps as part of a third party as-

surance review), when processing is particularly risky

(e.g. before such processing, with documentation

generated via Data Protection Impact Assessments),

or using ongoing certification to provide flexibility

(for example, as is the case with Binding Corporate

Rules).

Retrospective accounts are reactive and can either

describe a legitimate event - in which case they can be

either periodic or produced upon request (e.g., trig-

gered by a spot check by a regulator) – or an unex-

pected event, such as a data protection breach.

Furthermore, an interesting distinction can be

made between what may be regarded as static ac-

counts, as opposed to dynamic accounts. The for-

mer do not vary over time, whereas the latter take

into account parameters that may change over time.

For instance, an example of a dynamic account would

be a CSA Open Certification Framework (OCF) level

3 account, which is an example of a dynamic certi-

fication. Indeed, it could be argued that yearly or

monthly audits are irrelevant in an environment that

changes completely on a daily or hourly basis, as

is often the case with cloud computing. Continuous

compliance monitoring is essential to securely deliv-

ering cloud services and ensuring compliance. Cloud

services are inherently dynamic, because the dynamic

provisioning and de-provisioning of resources is a

key part of the cloud value proposition and business

model. Hence, automation for operations and asset

management are essential in this dynamic environ-

ment and verification of compliance with policy and

legislation – such as the EU Data Protection Directive

1995 (Directive 95/46/EC), Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

(GLBA), US federal Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA) 1996, and export com-

pliance controls like the International Traffic in Arms

Regulations (ITAR) – requires continuously running

automation. Accounts can be also regarded as a pro-

cess, for example a process of storytelling and expla-

nation.

3.3 Attributes of the Account

Although the description of the event or process is an

essential element, the account should also carry the

following attributes:

• Recipient: This is the actor who receives the ac-

count. Depending on the recipient, the level of

detail in the description of the event may change.

• Event/Process description

• Evidence: Relevant information to support expla-

nation and justification about assertions

• Measures for remediation (if incident)

• Timestamp and signature: The accountable organ-

isation is of course responsible for producing the

account and therefore should sign the entire report

including the date.

Accounts of legitimate events may be periodic and

could sometimes be used as evidence for prior events

whenever an incident happens in the future. A times-

tamp in the report hence becomes mandatory.

Putting the "Account” into Cloud Accountability

11

3.4 Interactions between Cloud Actors

Related to Accounts

First we set out the general context in which accounts

are produced, and then the process of generating and

verifying an account.

As discussed further within the A4Cloud concep-

tual framework (Felici et al., 2014), a cloud actor (ac-

countor) is accountable to certain other cloud actors

(accountees) within a cloud ecosystem for:

• Norms: the obligations and permissions that de-

fine data practices; these can be expressed in

policies and they derive from law, contracts and

ethics.

• Behaviour: the actual data processing behaviour

of an organisation.

• Compliance: entails the comparison of an organi-

sation’s actual behaviour with the norms.

For our purposes, the accountors are cloud actors

that are organisations (or individuals with certain re-

sponsibilities within those) acting as a data steward

(for other people’s personal and/or confidential data).

The accountees are other cloud actors, that may in-

clude private accountability agents, consumer organ-

isations, the public at large and entities involved in

governance.

Contracts express legal obligations and business

considerations. Also, policies may express business

considerations that do not end up in contracts. En-

terprise policies are one way in which norms are ex-

pressed, and are influenced by the regulatory environ-

ment, stakeholder expectations and the business ap-

petite for risk. By the accountor exposing the norms

it subscribes to and the things it actually does, via an

account, an external agent can check compliance.

3.5 Accounts Shown to Different Data

Protection Roles

Generally speaking, the sort of information that an or-

ganisation needs to measure and demonstrate in such

an account includes: policies; executive oversight;

staffing and delegation; education and awareness; on-

going risk assessment and mitigation; program risk

assessment oversight and validation; event manage-

ment and compliance handling; internal enforcement;

redress (Accountability Phase, 2010; ICO, 2012).

Existing organisational documents can often be used

to support this analysis (nymity, 2014). Measure-

ment of the achievement needs to be done in conjunc-

tion with the organisation and the external agents that

judge it, which is dependent upon the circumstances,

and to other entities that may need to be notified.

Some examples of accounts that may be provided to

cloud actors fulfilling certain data protection roles in

a given context are shown in Table 1.

3.6 Verification of Accounts

It is not just a question of interaction between actors

in the provision of accounts, but also in the verifi-

cation of accounts. Verification methods may differ

across the different forms of account in the cloud, as

considered further below. As briefly mentioned in

section 3, the company Nymity (nymity, 2014) has

provided an example structure for evidence and asso-

ciated scoring mechanism for accountability based on

existing documentation that can form some of these

types of accounts – but some organisations may want

to take a different approach and so this should not

be regarded as a standard. The Nymity accountabil-

ity evidence framework is intended for collecting ev-

idence in a single organisation and for demonstrat-

ing accountability that is structured around 13 privacy

management processes (nymity, 2014).

There are different levels of verification for ac-

countability, as proposed by Bennett (Bennett, 1995),

which correspond to policies (the level at which most

seals programmes operate), practices and operations.

It is very weak to carry out verification just at the

first of these levels – instead, mechanisms should

be provided that allow verification across all levels.

Most privacy seal programmes just analyse the word-

ing in privacy policies without looking at the other

levels, and thus provide verification only at this first

level (of policies). The second level relates to in-

ternal mechanisms and procedures, and verification

can be carried out about this to determine whether

the key elements of a privacy management framework

are in place within an organisation. Few organisa-

tions however currently subject themselves to a ver-

ification of practices, and thereby being able to prove

whether or not the organisational policies really work

and whether privacy is protected in the operational en-

vironment. To do this, it seems necessary to involve

regular privacy auditing, which may need to be exter-

nal and independent in some cases.

In terms of the verification process, there are vari-

ous different options about how this may be achieved.

There could for example be a push model in terms

of the account being produced by organisations or

else a pull model from the regulatory side; the pro-

duction of accounts could be continuous, periodic or

triggered by events such as breaches. In general,

there should be spot checking by enforcement agen-

cies (properly resourced and with the appropriate au-

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

12

Table 1: Accounts provided by whom to whom and in what circumstances.

Type of Account Data Protection Roles Example Cloud Actor produc-

ing the Account

Account for self-certification/

verification

Data Controller (DC), for Data

Protection Authorities (DPAs)

and their customers

Organisational Cloud Customer

Periodic internal reviews (to

check that mechanisms are op-

erating as needed and update if

required)

DC or Data Processor (DP), for

themselves or auditors

Organisational Cloud Customer,

Cloud Provider

Evidence provided by risk anal-

ysis, PIAs and DPIAs (includ-

ing assessment along the CSP

chain and how this was acted

upon)

DC, for DPAs and their cus-

tomers

Organisational Cloud Customer

External certification e.g.

BCRs, CBPRs, CSA OCF

level 3, privacy seals, account-

ability certifications, security

certifications

DC or DP, for certification bod-

ies (evidence for certification)

or for customers (evidence of

certification)

Organisational Cloud Customer,

Cloud Provider

External audit (ongoing) DC or DP, for auditors (evi-

dence) or customers (audit out-

put)

Organisational Cloud Customer,

Cloud Provider

Verification by accountability

agents

DC to agent, output to DPA Organisational Cloud Customer

Evidence about fault if data

breach

DC to Data Subject (DS), DC to

DPA, DP to DC, DP to DP

Organisational Cloud Customer,

Cloud Provider

thority) that comprehensive programmes are in place

in an organisation to meet the objectives of data pro-

tection. There could in some cases be certification

based on verification, to allow organisations to have

greater flexibility in meeting their goals.

It is often regarded as underpinning an

accountability-based approach that organisations

should be allowed greater control over the practical

aspects of compliance with data protection obliga-

tions in return for an additional obligation to prove

that they have put privacy principles into effect (see

for example (Weitzner et al., 2008)). Hence, that

whole approach relies on the accuracy of the demon-

stration itself. If that is weakened into a mere tick box

exercise, weak self-certification and/or connivance

with an accountability agent that is not properly

checking what the organisation is actually doing,

then the overall effect could in some cases be very

harmful in terms of privacy protection. As Bennett

points out ( (Bennett, 2012) p. 45), due to resource

issues regulators will need to rely upon surrogates,

including private sector agents, to be agents of

accountability, and it is important within this process

that they are able to have a strong influence over the

acceptability of different third party accountability

mechanisms.

In particular, it is important that the verification

is carried out by a trusted body that does not collude

with the accountor, and that it is given sufficient re-

sources to carry out the checking, as well as there be-

ing enough business incentive (for example, via large

fines) that organisations wish to provide appropriate

evidence to this body and indeed implement the right

mechanisms in the first place.

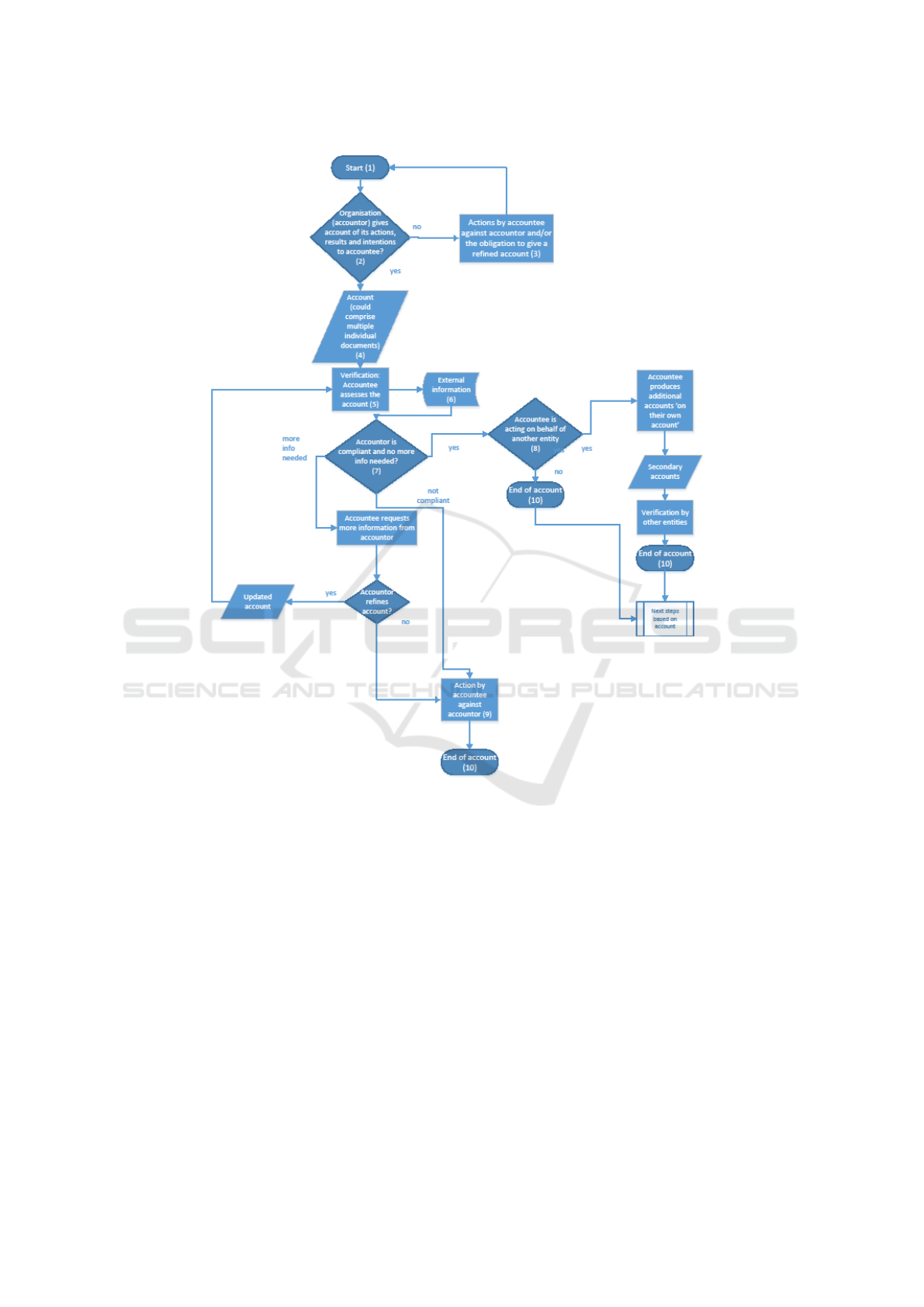

The overall process around verification of an ac-

count is summarised within Figure 2.

First of all, there is a certain context in which the

‘start’ – labelled (1) within Figure 2 - would apply,

in other words the context in which an organisation

might need to give an account, or might wish to do

this voluntarily. Broadly speaking, these situations re-

quiring or involving production of an account may be

characterised as follows:

• Regulatory obligation: The most typical situation

where there is a legal obligation to produce an ac-

count is where governmental bodies or regulatory

Putting the "Account” into Cloud Accountability

13

Figure 2: High-level view of the provision and verification of an account.

agencies enforce rights or obligations, by means

of an investigation, a request for information or a

spot check by a Data Protection Authority (DPA).

• Contractual undertaking: A legal obligation could

instead come from the organisation itself, for in-

stance from a contractual obligation to give an

account. The cloud service provider may have

given a contractual obligation in its terms of ser-

vice or in a SLA that it would provide an ac-

count (for example, a data breach notification pro-

cedure) or that it would demonstrate compliance

in some way. Another situation may be that the

Cloud Service Provider (CSP) has undertaken to

get third party certification for compliance or for

some process and so is required by the third party

to give an account of certain processes in order to

get certification.

• Voluntary undertaking to give an account: The

CSP may just state (in a policy published on its

website for example) that it would provide an ac-

count in certain circumstances or make ‘best ef-

forts’ to do so. Many policies published in this

way are not legally binding or may not be incor-

porated into the contract between the CSP or the

customer, so the CSP can refuse to give the ac-

count or may claim that it cannot do so and has

made a ‘best effort’.

Next, supposing this context is in place, the organ-

isation (as accountor) is supposed to give account of

not only its actions, but also its results and intentions

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

14

to the accountee cf. (2) in Figure 2. Exactly what

must be provided will vary according to the context;

for example, specific information will be expected in

the case of the accountor wishing to be certified.

If an organisation gives no account in the first

place, there should be repercussions about this that

might include the obligation to give a refined account,

defined according to the accountees’ or assessors’

needs, cf. (3) in Figure 2. For example, in the case of

regulatory requests, the consequences could be fines.

In the case of contractual undertakings, failure to pro-

duce an account would be a breach of contract that

entitles the customer to damages, or service credits

(for breach of SLA) or gives a right to the customer to

terminate the contract without notice. Failure to pro-

duce an account needed for a third party certification

of compliance would mean that the CSP could not ob-

tain the certification. This may have direct legal con-

sequences for the relationship between the CSP and

its customer (depending on whether this was a condi-

tion of the contract) because the customer may decide

to terminate or not to renew the contract. In the case

of a voluntary undertaking, although there would be

no legal redress for the customers, the consequences

of refusal to give an account may involve damage to

its reputation by disgruntled customers.

If the organisation does provide an account, this

can result in one or more documents being provided,

or information being captured by other means, as the

account provided by the organisation could be writ-

ten or oral, cf. (4) in Figure 2. For further informa-

tion, see for example (Vranaki, 2016) which expands

upon real life cases in which multiple accounts can

be created by a Data Controller for presentation to a

regulator.

The accountee then assesses the account (5), po-

tentially making reference to additional information

(6). The level of satisfaction with the account is

gauged (7), in the sense that the account may be

judged to show that the organisation is compliant (if

appropriate), or else may be judged to provide a sat-

isfactory explanation about a data breach event. On

the other hand, the accountee may judge the organ-

isation to not be compliant (and hence for example,

not issue a certificate of compliance) (9), or wish to

have additional information about the event. Espe-

cially in the case of a data protection report, the ac-

countee probably requires more than just information,

in other words clarification, explanation, updating and

also most probably corrective action. Hence, even if

the account process is complete in the sense that the

accountee may accept the account is accurate and may

be satisfied with it, it could be that they are not sat-

isfied in the sense that the account shows that some

action/omission has caused and is causing harm and

needs additional action. For this reason, the ‘End of

account’ (10) may only be the start of another process,

even if the accountee is satisfied with the account.

‘Next steps based on account’ reflects that this pro-

cess may follow; it could include for example reme-

diation, actions based on the account, further investi-

gation, etc. After all, an account of a breach should

contain something about ongoing corrective action.

Accountability agents or other third parties could

be used to provide verification of accounts, and serve

as an intermediary to the ultimate accountees, some

of whom may impose sanctions (8). If, as considered

within D:C-2.1 (Felici et al., 2014), there is a good

trust relationship between such an agent and the ac-

countee, then the agent’s account is likely to be di-

rectly accepted by the other accountees.

The account process is taken to finish (10) if ei-

ther an account has been provided that is found to be

satisfactory by the accountee or an agent acting on its

behalf, or the account is not found to be adequate and

appropriate actions are taken by the accountee against

the accountor. However, this notion of ‘finishing’ is

too coarse-grained, as discussed above. Furthermore,

accountability is not a binary state, but has a certain

level of maturity. Correspondingly, accounts have a

certain effectiveness and appropriateness. Depending

on the maturity an accountee may be satisfied or not,

and the threshold of this maturity might differ depend-

ing on the accountees or the event about which one is

asked to give an account. Hence, more mature ac-

count might be provided, or different ones for differ-

ent accountees, events, etc., so this is another reason

why ‘End of account’ is not necessarily an end state,

but the process might be repeated from the start with

a different degree of maturity or threshold.

Sanctions might be applied at several points, no-

tably if the organisation does not provide an account

in the first place (3), if it fails to respond adequately

to the dialogue with the assessor, or if the assessor is

not satisfied in respect to the accounts produced (9).

In fact, the use of the word ‘sanction’, here mean-

ing a consequence of an inadequate or non-provision

of an account, is avoided when listing accountabil-

ity artefacts (Gittler et al., 2016), because in legal

terms ‘sanction’ refers to a punishment imposed by

a legal or regulatory authority, for example fine, im-

prisonment of penalties for disobedience, whereas we

also want to include non-regulatory actions imposed

by the accountee, which is perhaps the customer, and

this could for example mean contract termination or

perhaps a contractual penalty for failure to produce a

report. Such consequences or repercussions are there-

fore represented quite broadly in Figure 2 as actions

Putting the "Account” into Cloud Accountability

15

by the accountee against the accountor.

The process of providing an account could be

quite complex, and this is just a generic overview

of that process. There could be multiple documents

that in the form described here provide an account,

but each of which may be viewed as an individual ac-

count, and perhaps even have a slightly different pro-

cess flow. For example, multiple accounts provided

by different parties within an organisation could be

aggregated by a senior officer, who acts as a commu-

nication interface with the accountee (in this case, the

regulator); this officer would interact further if needed

with the various internal teams that produced the ac-

counts if further information is required.

The element of responsiveness is not necessarily

in the account itself, yet in the interaction between

what the account should be about (and how it should

be refined if deemed inappropriate) and in the estab-

lishment of the account objects, i.e. the norms that

need to be compared with actual behaviour (com-

pliance). Part of the norms to which actual (sys-

tem) behaviour is compared should be defined in a

two-way communication (dialogue) between cloud

providers and external stakeholders, which includes

cloud users, regulators and the public at large.

The process of generating and verifying accounts

for certification could be more specialised than the

flow shown in Figure 2 (for example, it could involve

assessment by multiple parties) and would need to

be adapted as the purpose of verification of the ac-

count and possible outcomes would differ, i.e. result

in a certain level certification, or no certification being

given.

This flow shown in Figure 2 is a generic flow that

could apply in range of contexts and is not cloud-

specific. With regard to cloud contexts, as with other

service provision delivery contexts involving a chain

of providers, provision of an account might involve

chaining of accounts. For example, an account pro-

vided by an organisation using the cloud that is act-

ing in the capacity of a data controller, to a data pro-

tection authority might be constructed using accounts

that had previously been provided to it from the cloud

service providers that it was using.

4 DISCUSSION

Accountability is a difficult concept to define, and

many European languages even lack a word for it.

Numerous definitions of accountability exist in differ-

ent domains (such as public policy, financial sector or

enterprise operations), and each focuses on slightly

different, context specific, aspects. Hence there is

no consensus on a single definition. The EU Gen-

eral Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (EU, 2016)

defines accountability as being “responsible for, and

be[ing] able to demonstrate compliance with [princi-

ples relating to processing of personal data]” (Arti-

cle 5), and details many accountability elements in-

cluding (in Article 22) a list of a Data Controller’s

accountability instruments:

• Policies

• Documenting processing operations

• Implementing security requirements

• Data Protection Impact Assessments

• Prior authorisation/consultation by Data Protec-

tion Authorities (DPAs)

• Data Protection Officer

• If proportional, independent internal or external

audits

Ten years ago, Lampson (Lampson, 2004) listed

accountability as one of the three core objectives of

having a security policy, alongside usage control and

availability. It is thus surprising that accountability

has had such a little impact on the Cloud services that

are currently on offer.

The big Cloud providers that currently dominate

the international market have such economic power

that they effectively could ignore any European at-

tempts at forcing them to run their business the way

the European Union (EU) thinks they should. How-

ever, the GDPR (EU, 2016), with its significantly

higher economic penalties, is poised to change that.

What we have presented is only part of the puzzle

for modern services. The kind of tools that we have

outlined (Jaatun et al., 2016) will need to be comple-

mented by other security tools to make security and

privacy stronger, for instance by enforcing confiden-

tiality and anonymity where desired.

5 CONCLUSION

In this paper we have presented fundamental require-

ments that we believe must be met by Cloud providers

wishing to be accountable stewards of their cus-

tomers’ data.

The kinds of tools we have outlined (Jaatun et al.,

2016) all contribute to an accountability-based ap-

proach, increasing transparency for Cloud users, and

enabling Cloud providers to “do the right thing” with

respect to accountability along the provider chain.

We believe that providers soon will be required to

justify their practices and mechanisms for handling

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

16

customers’ data to external parties (Pearson, 2013),

and that a certification scheme inevitably will emerge,

much like we see for the Payment Card Industry Data

Security Standard (PCI-DSS, 2013).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been partly funded from the Euro-

pean Commissions Seventh Framework Programme

(FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no: 317550

(A4CLOUD) Cloud Accountability Project, and

builds substantially on our previous journal paper

(Jaatun et al., 2016) and project deliverables (Gittler

et al., 2016) Thanks to all our A4Cloud partners, and

particularly Fr

´

ed

´

eric Gittler, Ronald Leenes, Maartje

Niezen, Niamh Gleeson and Dimitra Stefanatou for

their contribution to the research reported in this pa-

per.

REFERENCES

Accountability Phase, I. (2010). Demonstrating and mea-

suring accountability a discussion document.

Bennett, C. (1995). Implementing privacy codes of practice.

CSA - PLUS 8830-95.

Bennett, C. J. (2012). The accountability approach to pri-

vacy and data protection: Assumptions and caveats. In

Managing privacy through accountability, pages 33–

48. Springer.

Cattaneo, G., Kolding, M., Bradshaw, D., and Folco, G.

(2012). Quantitative estimates of the demand for

cloud computing in europe and the likely barriers to

take-up. Technical Report SMART 2011/0045 D2 In-

terim Report, IDC.

CIPL (2009). Data Protection Accountability: The Es-

sential Elements - A Document for Discussion (the

Galway project). http://www.huntonfiles.com/files/

webupload/CIPL Galway Accountability Paper.pdf.

EU (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Par-

liament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the

protection of natural persons with regard to the pro-

cessing of personal data and on the free movement of

such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General

Data Protection Regulation). L, 119.

Felici, M., Pearson, S., Dziminski, B., Gittler, F., Koulouris,

T., Leenes, R., Niezen, M., Nu

˜

nez, D., Pannetrat,

A., Royer, J.-C., Stefanatou, D., and Tountopoulos,

V. (2014). Conceptual framework. Technical Report

D:C-2.1, A4Cloud Project.

Gittler, F., Pearson, S., Brown, R. M., Koulouris, T., Leenes,

R., Niezen, M., Nu

˜

nez, D., Pannetrat, A., Royer, J.-

C., Stefanatou, D., Tountopoulos, V., Luna, J., Had-

dad, M., Sellami, M., Azraoui, M., Elkhiyaoui, K.,

´

’Onen, M., Gleeson, N., Vranaki, A., Oliveira, A.

S. D., Bernsmed, K., Jaatun, M. G., Corte, L. D., and

Gago, C. F. (2016). Reference architecture. Technical

Report D:D-2.4, A4Cloud Project.

ICO (2012). Guidance on the use of cloud computing.

Jaatun, M. G., Pearson, S., Gittler, F., Leenes, R., and

Niezen, M. (2016). Enhancing accountability in the

cloud. International Journal of Information Manage-

ment.

Lampson, B. W. (2004). Computer security in the real

world. Computer, 37(6):37–46.

nymity (2014). Privacy management accountability frame-

work.

PCI-DSS (2013). Payment Card Industry Data Security

Standard.

Pearson, S. (2013). On the relationship between the differ-

ent methods to address privacy issues in the cloud. In

Meersman, R., Panetto, H., Dillon, T., Eder, J., Bellah-

sene, Z., Ritter, N., Leenheer, P., and Dou, D., editors,

On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems: OTM

2013 Conferences, volume 8185 of Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, pages 414–433. Springer Berlin

Heidelberg.

Pearson, S. (2017). Strong accountability and its contribu-

tion to trustworthy data handling in the information

society. In Stegh

¨

ofer, J.-P. and Esfandiari, B., ed-

itors, Trust Management XI, pages 199–218, Cham.

Springer International Publishing.

Pr

¨

ufer, J. (2013). How to Govern the Cloud? Characterizing

the Optimal Enforcement Institution that Supports Ac-

countability in Cloud Computing. In Cloud Comput-

ing Technology and Science (CloudCom), 2013 IEEE

5th International Conference on, volume 2, pages 33–

38.

Rong, C., Nguyen, S. T., and Jaatun, M. G. (2013). Be-

yond lightning: A survey on security challenges in

cloud computing. Computers & Electrical Engineer-

ing, 39(1).

Vranaki, A. A. (2016). Learning lessons from cloud inves-

tigations in europe: Bargaining enforcement and mul-

tiple centers of regulation in data protection. U. Ill. JL

Tech. & Pol’y, page 245.

Weitzner, D. J., Abelson, H., Berners-Lee, T., Feigenbaum,

J., Hendler, J., and Sussman, G. J. (2008). Infor-

mation accountability. Communications of the ACM,

51(6):82.

APPENDIX

Abbreviations

BCR: Binding Corporate Rules

CBPR: Cross-Border Privacy Rules

CSA: Cloud Security Alliance

CSP: Cloud Service Provider

DC: Data Controller

DP: Data Processor

DPA: Data Protection Authority

Putting the "Account” into Cloud Accountability

17

DPIA: Data Protection Impact Assessment

DS: Data Subject

OCF: Open Certification Framework

PIA: Privacy Impact Assessment

PCI-DSS: Payment Card Industry Data Security

Standard

CLOSER 2019 - 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science

18