ShoCons: Effective Display of Shortcuts in Icon Toolbars

Vidya Setlur and Benjamin Watson

a

Tableau Research, Palo Alto, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Keyboard Shortcuts, Menus, Toolbars, Icons.

Abstract:

Users often do not use keyboard shortcuts in applications as recalling and choosing the correct shortcut is a

higher-order cognitive task. Mouse driven menus, toolbars, and icons are easier for a user to learn because

they present hints and make visible what operations are possible, drawing on the power of recognition rather

than recall. How can we better support the usage of shortcuts with such menus? Two existing methods are text

in the icons, and popups with mouse hover. While the first is space inefficient; the second limits exposure and

imposes an interaction cost. We propose a third method, ShoCons, that is spatially more efficient and neither

limits user exposure nor imposes an interaction cost. To achieve this, ShoCons use a succinct iconic display of

meta keys, limiting textual display to one character. We examine these alternatives in a controlled study, and

find that when used with a high-level task, ShoCons enable faster task performance and an immediate increase

in the accuracy of shortcut use.

1 INTRODUCTION

Making functionality easier to access for users is a

problem common to all interactive software. Tool-

bars are prevalent in graphical user interfaces because

they make visible what operations are possible, sub-

stituting the ease of recognition for the difficulty of

recall, making the interface easier to learn. Icons are

commonly used in toolbars as they are visually dis-

tinctive, and can succinctly convey the semantics of

the underlying information (Familant and Detweiler,

1993).

A keyboard shortcut is a combination of

keystrokes used to carry out some operation that

would otherwise be executed with the mouse. In

desktop applications, most shortcuts use one or more

metakeys (i.e., the Ctrl, Alt, and Shift keys) in com-

bination with another key, creating a chord. Because

they allow users to perform operations without devi-

ating significantly from their tasks, they are generally

viewed as more efficient than using icons in toolbars

(Lane et al., 2005). As users transition from being

novices to experts, one would expect them to employ

shortcuts more often. Unfortunately this is not the

case. Shortcuts can be hard to learn and remember,

because unlike menus and toolbars, they often have

no visual representation (Lane et al., 2005).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3758-7357

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Shortcut Display in Icons

There are two prevailing methods for displaying key-

board shortcuts. Pop-ups display on demand a textual

representation of the shortcut next to the correspond-

ing icon, and are often used with toolbars. For ex-

ample, Microsoft Office displays a tooltip when the

cursor hovers over an icon. Pop-ups preserve the visi-

bility of icons, but hide the keyboard end of the short-

cut mapping, requiring user action before making it

completely visible. This limits the both the exposure

to and incidental learning of mappings that is impor-

tant to effective integration of shortcuts in interfaces

(Grossman et al., 2007). Static or continuous hints

always display a textual representation of the short-

cut, and are regularly used in text menus such as OS

X. While they can display both ends of the shortcut

mapping, the display space they dedicate to key dis-

play can reduce the visibility of the mapping to appli-

cation functionality.

2.2 Measuring Usage and Efficacy of

Keyboard Shortcuts

Lane et al. explored the efficiency of shortcuts (2005),

finding that once learned, drop-down menus are less

Setlur, V. and Watson, B.

ShoCons: Effective Display of Shortcuts in Icon Toolbars.

DOI: 10.5220/0008494502290234

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2019), pages 229-234

ISBN: 978-989-758-376-6

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

229

Figure 1: ShoCons encodings for various shortcut metakey

combinations. Hash marks in the border of the ShoCons

correspond to the positioning of the Alt, Control and Shift

metakeys on a QUERTY keyboard.

efficient than icon toolbars, and toolbars are less ef-

ficient than shortcuts. In another study, Odell et al.

examined the efficiency of toolbars, shortcuts phys-

ically grouped by related functionality, and shortcuts

mapped to keys with a lexical relationship to the func-

tion’s name (Odell et al., 2004). They found that

physically grouped shortcuts were fastest, while tool-

bars were slowest. The literature on flow applied to

user interfaces provides a good motivation for why

users should make the transition from icon toolbars to

keyboard shortcuts (Bederson, 2004). Bederson de-

scribes different levels of skill acquisition, where in

the final autonomous stage, the command is almost

exclusively facilitated by keyboard shortcuts.

Several researchers worked toward easing the

transition to shortcuts. Grossman et al. (2007) found

that audio display of shortcut mappings and disabling

command access through menus was quite effective.

In the Blur system (Scarr et al., 2011), when the user

executes a command using a toolbar, Blur displays a

transient, visual “calm notification” reminding them

of the equivalent shortcut. When arranging several

objects in Powerpoint, Blur users made the expert

transition more easily than with traditional shortcuts.

ExposeHK overlays key combinations onto existing

UI widgets when a metakey is pressed (Malacria

et al., 2013), making shortcuts visible on demand.

3 CONTRIBUTIONS

We propose a new method of shortcut display called

ShoCons, which uses a succinct iconic representation

of shortcut metakeys (Shift, Ctrl and Alt) that mirrors

the layout of those keys on the QWERTY keyboard

(Figure 1). Our work:

• Demonstrates the Potential of Continuous Short-

cut Display. Rather than making display of short-

cut mappings conditional on mouse (Grossman

et al., 2007) or keyboard interaction (Malacria

et al., 2013) (Scarr et al., 2011), ShoCons en-

ables continuous display of shortcuts, increasing

the visibility of shortcut keyboard mappings. This

simplifies their discovery, eases their confirma-

tion, and better supports the incidental and as-

sociative learning described by Grossman et al.

Our experiments show that ShoCons’ continuous

shortcut display can significantly improve task

performance and accuracy of shortcut use.

• Proposes and Verifies a Visually Efficient Short-

cut Display. Continuous display of shortcut map-

pings might overload the interface, which is al-

ready quite busy in complex applications, and

may introduce a tradeoff that obscures the very

functionality mappings it hopes to reveal. Our ex-

periments confirm that ShoCons offers significant

improvements in task performance and accuracy

of shortcut use over a less concise, continuous

shortcut display.

• Examines Shortcut Usage in a Higher Level Con-

text. Most previous work on shortcuts evaluated

their effectiveness using disjoint, short, repetitive

tasks (e.g., “press ‘A’ now”) to accelerate and en-

able the study of learning in the lab. Inspired by

Scarr et al.’s (2011) use of a higher-level Power-

point layout task to improve the external valid-

ity of their evaluation, we use a high-level garden

building task to evaluate ShoCons. Our experi-

ments suggest that even in this challenging con-

text, ShoCons can enable rapid improvements in

task performance and accuracy of shortcut use.

4 EVALUATING SHOCONS

To test whether ShoCons’ continuous display of short-

cut mappings could improve task performance and

shortcut learning, we performed an experiment com-

paring our continuous, succinct ShoCons display to

a a traditional continuous shortcut display (verbose,

Figure 3(a)), and a popup display that shows map-

pings only when the Alt key is pressed (conditional,

Figure 3(a)). We hypothesized that:

• Continuous is Better: Continuous display (ver-

bose & ShoCons) enables better task performance

and learning than conditional display.

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

230

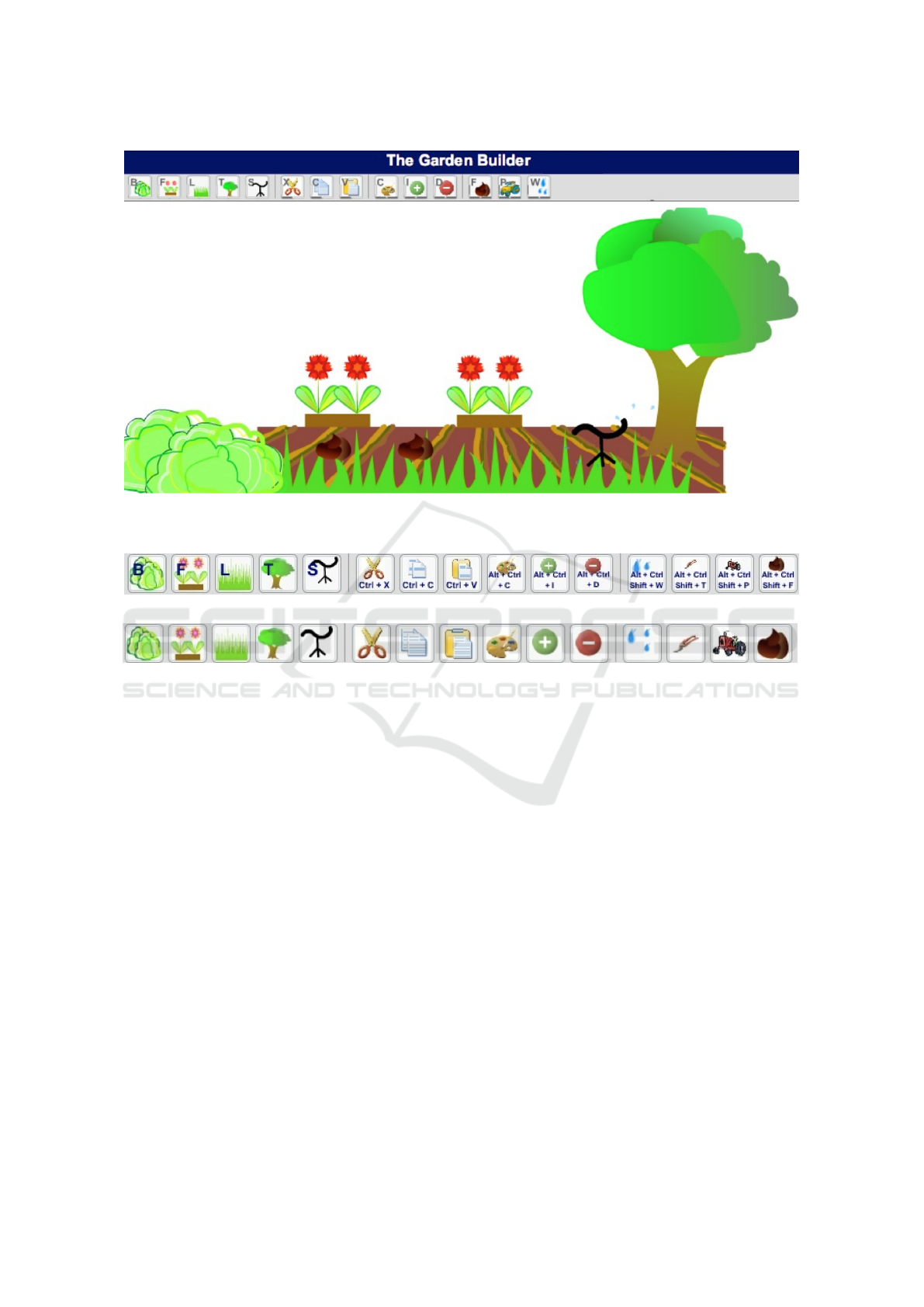

Figure 2: Experimental interface with ShoCons (continuous succinct) display in the toolbar and a participant’s garden. We do

not show the very similar target garden at the bottom.

(a) Text in the icon (continuous verbose)

(b) Popups (conditional)

Figure 3: The other two different experimental shortcut displays in addition to ShoCons. There are no popups in (b) because

the user has not just pressed the Alt key.

• Succinct is Better: Succinct continuous display

(ShoCons) enables better performance and learn-

ing than verbose display.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants and Apparatus

18 participants aged from 25 to 45 took part in our ex-

periment, all with normal or corrected-to-normal vi-

sion. They used a Windows 7 2.0GHz 4GB PC with

a 1280 × 1024 LCD monitor, mouse, and keyboard.

4.1.2 Task and Stimuli

In each trial, participants used a computerized gar-

dening interface to recreate a target garden (Figure

2). A successful recreation matched the target gar-

den by having the same number, types and sizes of

objects, placed in the same vertical and horizontal or-

ders. The gardening interface showed a toolbar at the

top with an icon for each possible garden operation,

a display below of the participant’s current garden,

and the target garden at the bottom. Gardens were

made up of five object types including grass, flowers,

bushes, trees and sprinklers, each of which could vary

in location and size (except fixed size sprinklers). Tar-

get gardens varied in both the complexity of the tar-

get, and of the shortcut key combinations that could

be used. All participants used the same gardens and

shortcut key combinations.

There were five operations for inserting objects

(one per type), six editing operations (cut, copy, paste,

color, insert and delete), and four maintenance oper-

ations (irrigating, pruning, plowing and fertilizing).

Maintenance operations either changed object state

(e.g. making sprinklers shoot water) or appearance

(e.g. fertilizing made objects larger). Maintenance

operations were present only if they could be used in

the current garden. Each icon had a matching key-

board shortcut. Icons in the toolbar displayed short-

cuts in one of the three ways discussed above: con-

ShoCons: Effective Display of Shortcuts in Icon Toolbars

231

tinuous succinct display (ShoCons, Figure 1 and the

top of Figure 2); continuous verbose display, with text

in the icon (Figure 3(a)); or conditional display, with

higher-contrast icon text appearing only when the Alt

key was pressed and disappearing with the next action

(Figure 3(b)). To interact with the interface, partici-

pants could click on an icon, or use the matching key-

board shortcut. To select an object, participants could

click on it, or use the tab key to cycle through them.

To move an object, participants could either drag it

with the mouse, or use arrow keys.

4.1.3 Procedure

We provided each participant with written instruc-

tions explaining their task and illustrating each of

the shortcut displays. The instructions asked partic-

ipants to complete each task as quickly as possible,

use shortcuts as often as they were able, and take

breaks as needed between any two trials. To gain

some familiarity with the gardening interface and the

different shortcut displays without also beginning to

learn about their combination, participants practiced

each in isolation: they built simple gardens using a

purely textual interface without shortcuts until suc-

cessful twice, and then practiced with each short-

cut display without gardening functionality until they

input the matching keystrokes twice. The interface

displayed a visual message informing participants of

when they successfuly completed the garden. How-

ever, participants were free to continue to the next

garden before this message appeared, causing an er-

ror. On average, only 3 of a participant’s 108 gardens

were errors.

4.1.4 Design

We used a two-factor (3 shortcut displays x 3 blocks)

design. Both variables were within subject. Short-

cut display showed shortcut key mappings to partici-

pants using verbose, ShoCons or conditional display.

Blocks formed trials within each shortcut display into

three sequential groups, letting us sample the learning

process. To control for learning interference between

different shortcut displays, the order in which par-

ticipants worked with different shortcut displays was

completely counterbalanced across subjects. More-

over, as in Grossman et al. (2007), each participant

used three different key mappings, so that learning

of key mappings would not continue as shortcut dis-

play varied. All participants experienced the same key

mappings, but their order and pairing with shortcut

display was completely counterbalanced across sub-

jects.

As dependent measures of task performance, we

used time, the average number of seconds elapsed be-

tween target garden display and trial completion; and

error, the percentage of trials completed incorrectly.

To measure shortcut usage we recorded achievement,

the proportion of all operations executed that were

shortcuts; and accuracy, the proportion of the num-

ber of all key combinations that successfully executed

a shortcut. There was no reason to use key combi-

nations unless one was attempting a shortcut, so ac-

curacy measured the success of participants when at-

tempting to use shortcuts.

Participants performed 108 trials: 36 with each

display, with each block containing 12 trials. Aver-

age trial time was 27.67 seconds, meaning that par-

ticipants finished their trials in just under 50 minutes.

The number of commands performed per garden var-

ied between 2 and 11, with a median of 5.

4.2 Results

For all of our analyses, we averaged the times, errors,

achievement and accuracy within each block. Each

block contained 12 trials, producing 9 aggregated tri-

als from the original 108 for each participant: one for

each combination of shortcut display and block.

To confirm that key mapping and shortcut dis-

play order did not cause a confound in our results,

we performed a four-way ANOVA (key mapping, dis-

play order, shortcut display and block) that included

these experimental parameters as independent vari-

ables. Neither had any significant main effects, nor

any meaningful interactions with display or block.

We therefore performed a 2-way ANOVA on

shortcut display and block alone. We found no effects

on achievement (overall achievement was 51%), and

while block significantly affected error (F(2, 34) =

4.35, p < 0.01), its effect size was quite limited,

changing error from 1.8% to 4.6%, an increase of

roughly 1 in 36 gardens per display. We therefore

confine our remaining discussion of results to time

and accuracy.

In a 2-way ANOVA, shortcut display had sig-

nificant main effects on both time (F(2,34)=2833.5,

p < .0001) and accuracy (F(2,34)=84.5, p < .0001).

Block had no effect, and did not interact significantly

with display.

Figure 4 shows the effects on time. Significant

pairwise comparisons using contrasts showed that all

three mean times (34.16, 26.67 and 22.17 seconds;

σ = 10.91, 11.96 and 8.43) differed from one an-

other significantly. Both the verbose and ShoCons

displays enabled task performance that was meaning-

fully (22% and 35%) faster than performance with

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

232

Figure 4: Effects of shortcut display on time. The box cen-

ter is at median, the hinges are quartiles, and the whiskers

extend to the last data point less than 1.5 IHQ from the

hinge, where IHQ is the distance across the quartiles.

Figure 5: Effects of shortcut display on accuracy. Box plots

are configured as in Figure 4.

the conditional display. ShoCons communicated the

shortcut key mappings more clearly than the ver-

bose continuous display, permitting a performance

speedup of over four seconds.

Figure 5 shows the effects of shortcut display on

accuracy. Again significant pairwise comparisons us-

ing contrasts showed that all three means were signifi-

cantly different. While only two-thirds of shortcut at-

tempts with the conditional shortcut display were ac-

curate, 81% of the attempts with the verbose display

were, and 87% of the attempts with ShoCons were

(σ = 27%, 23% 18%). This difference in accuracy of

shortcut use likely explains much of the difference in

time between the conditional and continuous displays.

5 DISCUSSION

We begin our discussion with a review of our hypothe-

ses, and continue with two research questions.

Continuous is Better: This hypothesis was partially

confirmed. Continuous shortcut display did indeed

permit faster task performance than conditional dis-

play. It also enabled much more immediately accu-

rate use of shortcuts than conditional display. How-

ever, despite some promising trends across blocks, we

found no concrete evidence that continuous display

improves learning over time. Instead, the improve-

ments in task speed and shortcut accuracy were al-

most immediate.

Succinct is Better: This hypothesis was also partially

confirmed. The succinct ShoCons display permitted

faster task performance and immediate shortcut ac-

curacy than verbose display, even though its shortcut

hints were smaller than the verbose display’s. How-

ever, succinct display also did not clearly accelerate

shortcut learning over time. Rather, these improve-

ments were again almost immediate.

Why did Patterns of Shortcut Usage and Learn-

ing Differ from Previous Work? In previous re-

search (Grossman et al., 2007) (Scarr et al., 2011)

(Malacria et al., 2013), improved learning consis-

tently showed itself in significant differences in mea-

sured achievement (proportion of shortcut usage), and

faster improvement in achievement over time. Why

are these more gradual patterns absent in our results?

First, recall that we asked participants to maximize

shortcut usage. For this reason shortcut usage may

have rapidly reached a ceiling. Perhaps more im-

portantly, like Scarr et al. (2011), we used a high-

level experimental task with many components that

may have slowed shortcut learning, and certainly re-

duced the rate at which we could experimentally sam-

ple shortcut learning (with repetitious requests to ex-

ecute shortcuts). For example, note that selecting and

positioning objects was a central component of the ex-

perimental task, and that ShoCons did not display the

shortcuts for those operations. It may be that users re-

lied heavily on the mouse when positioning, limiting

achievement.

Will ShoCons Scale to Larger Interfaces? The

obvious objection to continuous display of shortcut

key mappings is that it adds additional information

to already busy interfaces. While it is fortunate that

ShoCons is more effective in communicating short-

cuts than the less succinct verbose display, the ob-

jection still holds. If shortcut display is indeed to be

continuous, it may prove impossible to eliminate this

concern entirely. However, it may be possible to mit-

igate it by throttling continuous display to match the

specific learning needs of a user.

6 LIMITATIONS

While our experimental task had many similarities to

Scarr et al.’s (2011), it was unusual, giving rise to a

unique pattern of results. Future work might replicate

ShoCons: Effective Display of Shortcuts in Icon Toolbars

233

or extend our evaluation of ShoCons and continuous

display by using a high-level task with a more com-

plete use of shortcut display, or a low-level task en-

abling a more direct comparison to prior work.

Even when succinct, continuous shortcut display

introduces tradeoffs between display of functionality

and shortcut mappings — the difference we found

between verbose and ShoCon task performance may

be evidence of this. Future work might explore this

tradeoff, e.g. by varying the complexity of the user

interface, or adjusting shortcut display salience to

match shortcut familiarity.

7 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we presented ShoCons, a visual tech-

nique that allows succinct and continuous display of

shortcut keyboard mappings in toolbars. We found

that when compared to standard alternatives for short-

cut display, ShoCons significantly speeds task perfor-

mance and improves accuracy during shortcut use;

even when that task contained significant components

(e.g cognitive planning and object positioning) that

did not benefit greatly from shortcuts.

Future work should examine the questions raised

by our work more closely. Does the improvement in

shortcut learning grow over the longer term in these

more complex task settings? Might an improvement

in learning as measured by achievement eventually

appear? Finally, what sort of information load does

continuous shortcut display place on user interfaces?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to our anonymous reviewers, who helped im-

prove this paper. We are also grateful to our psychol-

ogy colleague Anne McLaughlin for her statistical ad-

vice, and to the many Nokia Research employees who

participated in our experimental evaluation.

REFERENCES

Bederson, B. B. (2004). Interfaces for staying in the flow.

Ubiquity, 2004(September):1–1.

Familant, M. E. and Detweiler, M. C. (1993). Iconic refer-

ence: Evolving perspectives and an organizing frame-

work. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud., 39(5):705–728.

Grossman, T., Dragicevic, P., and Balakrishnan, R. (2007).

Strategies for accelerating on-line learning of hotkeys.

In Proc. ACM CHI, pages 1591–1600, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Lane, D. M., Napier, H. A., Peres, S. C., and Sandor, A.

(2005). Hidden costs of graphical user interfaces:

Failure to make the transition from menus and icon

toolbars to keyboard shortcuts. International Journal

of Human-Computer Interaction, 18(2):133–144.

Malacria, S., Bailly, G., Harrison, J., Cockburn, A., and

Gutwin, C. (2013). Promoting hotkey use through re-

hearsal with exposehk. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pages 573–582, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Odell, D. L., Davis, R. C., Smith, A., and Wright, P. K.

(2004). Toolglasses, marking menus, and hotkeys: a

comparison of one and two-handed command selec-

tion techniques. In Proc. GI, pages 17–24, Canada.

Canadian Human-Computer Communications Soci-

ety.

Scarr, J., Cockburn, A., Gutwin, C., and Quinn, P. (2011).

Dips and ceilings: Understanding and supporting tran-

sitions to expertise in user interfaces. In Proceedings

of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems, pages 2741–2750, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

CHIRA 2019 - 3rd International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

234