Fazil Say and His Musical Identity: Musical Embellishments in

“Black Earth”

Siti Nur Hajarul Aswad Shakeeb Arsalaan Bajunid, and Rizal Ezuan Zulkifly Tony

Faculty of Music and Performing Arts, Sultan Idris Education University, Tanjung Malim, Perak, Malaysia

Faculty of Music, MARA University of Technology, Selangor, Malaysia

{hajarulbajunid, rizaltony}@ gmail.com

Keywords: Embellishments, Modification, Fazil Say, Pianist.

Abstract: The role of a performer in the twenty-first century has progressed tremendously with regards to performance

practices developed from the Renaissance until the present. Many virtuosic performers currently perform

similar solo repertoire but with their own interpretation, which may result in score modifications. An

important question is: how does the performer modify the scores appropriately? This study examines Fazil

Say’s piano work of the Black Earth based on recorded performances. A musical analysis was conducted,

where transcriptions of four recorded live performances by Fazil Say were compared with the corresponding

music scores. This was to identify the melodic and rhythmic embellishment modifications that he made during

his live-recorded performances. These modifications were different in each performance. It is evident that

the role of a performer is not limited to interpreting dynamics, articulations, and pedalling, but also modifying

the score through melodic fragments and rhythmic patterns that can be considered one’s own interpretation

of the composers’ work. However, this may also apply to specific compositional works of contemporary

composers such as Fazil Say who is known as a performer, composer and improviser.

1 INTRODUCTION

Each performer has their own interpretation and

musical identity in their performances, whether

interpreting the classics or modern masterpieces.

With increasing numbers of virtuosic pianists being

trained through conservatories and competitions, it

has become more challenging to craft individual

artistry in order to sound different from the others.

The originality of their approach to sound warrants an

in-depth study, through listening to early and modern

recordings by pianists, then comparing them to

existing music scores.

There is a clear need to be highly imaginative in

interpreting the masterpieces to the best of the

performers’ abilities and skills. It is common for

pianists to modify music scores to accommodate their

interpretation and musicality. The most common

modifications are with dynamics, tempo alterations,

and embellishments, and these are typically found in

many musical studies. For example, Davidović’s case

study on the interpretation of Chopin’s Nocturne

Opus 27, No. 2 by Vladimir de Pachmann based on

three of his recording mediums: piano roll; acoustic

and electric recordings, where differences in tempo

alterations can be found; rhythmic alterations and text

variation; as well as dislocation and unnotated

arpeggiations in each recording medium (Davidović,

2016).

Although music scores are fixed, the musical

feelings and perspectives of each performer vary. The

musical feelings are based on reading the score and

music literature, exploring through practising, and

several performances.

In this paper, we focus on Fazil Say’s piano work

entitled “Black Earth”. Say is a contemporary Turkish

composer, performer and an improviser. We will

specifically discuss the melodic fragments and

rhythmic alterations applied by Say in four of his live-

recorded performances.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Fazil Say: Pianist

Fazil Say is a virtuosic pianist who performs

internationally. His work has been widely

acknowledged through several prestigious awards

228

Bajunid, S. and Tony, R.

Fazil Say and His Musical Identity: Musical Embellishments in “Black Earth”.

DOI: 10.5220/0008562502280233

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities (ICONARTIES 2019), pages 228-233

ISBN: 978-989-758-450-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

such as an Honorary prize at the Zelt-Musik-Festival

in Freiburg, the International Beethoven Award for

Human Rights, Peace, Freedom, Poverty Reduction,

and Inclusion, as well as a Music Award from the City

of Duisburg. He has also won an ECHO Klassik prize

for his complete recording of Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart's piano sonatas.

His interpretation of classic masterpieces,

including those by Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin, as

well as other works, have received positive reviews

from the media and audiences alike. However, this

highly successful pianist has also received criticism

about his interpretations of the classic masterpieces.

Most of his concerts are sold out prior to the event

based on the evidence from concert venues and also

his social media profiles. He has successfully created

his own interpretations and identity through his

performances that possibly persuade the listeners to

experience his live performances.

2.2 Embellishment

‘Embellishment’ is a well-known term in Western

classical music that refers to adding notes to a melody

and accompaniment lines on the keyboard or

modifying the rhythms to make a composition more

interesting. The Cambridge online dictionary defines

embellishment as, “to make something more beautiful

by adding something to it.” Robert Donington (2001)

defines embellishment in Groove Music Online as a

“decoration that includes both free and specific

ornamentation by adding the notation or using signs

in the notation or left to be improvised by a

performer” (Donington, 2001). The term

embellishments is not limited to a Western classical

approach but also applies those from other cultures in

a composition.

Historically, the practice of adding

embellishments was widely practiced during the

Renaissance. Virtuosic performers were expected to

improvise during the performance of each work.

There are several treatises and manuals for

performers to refer to as guidelines on how to

improvise. One of the first published books was the

“Opera Intitulata Fontegara” by Slyvestro di Ganassi

(1535). Singers during the Renaissance were

renowned for their improvised embellishments, using

the technique of diminution (Horsley, 1951). It is

evident that during this time, performers had the

freedom to apply their own embellishments in

performance.

However, composers of the eighteenth century

began to control the application of embellishments in

their works by notating them, or using a specific

symbol, giving the performer less freedom to apply

their own choices. According to Carl Phillip

Emmanuel Bach in his “Essay on the True Art of

Playing Keyboard Instruments”, a poor choice of

embellishments negatively affect the composers’

work, while too many good embellishments

sometimes create an imbalance in the works (Bach,

1974). Keyboardists were expected to improvise for

a position as an organist and perform for social

events. The practice of improvisation continued from

the Baroque up until the Classical period where

virtuosic musicians were composers, performers and

improvisers, such as J.S. Bach, Handel, Mozart, and

Beethoven.

During the nineteenth century, composers wrote

embellishments specifically for performers and

students of theirs to play as written. However, it was

primarily trained improvisers who were able to

improvise on music scores, and composers such as

Chopin and Liszt often improvised and added

embellishments to their own works and those of

others during performance.

In recent decades, the practice of Western

classical improvisation has been considered

demanding among musicians. There are several

virtuosic pianists who include improvisation as part

of their recital program, such as Gabriela Montero,

Robert Levine, David Dolan, Noam Sivan, among

others. Fazil Say has also improvised based on a

theme given by the audience in Turkey and Tokyo. In

this paper, we focus on Say’s embellishments during

his live-performances.

2.3 Modifying the Score

Hellaby (2009) describes modification as “more or

less to the original” music score, and either formal

(published) or informal (performer controlled).

Modifications that have been made by the performer

are documented in a score and categorised as ‘formal

modifications’. Informal modifications are more

flexible, and not written in a document but based on

the memory of the performer and their choice of what

to embellish in a original score (Hellaby, 2009).

It was common for pianists during the nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries to alter scores

(Hamilton, 2008). There was a period during which

some nineteenth century composers wrote their own

style of cadenza for other composers’ works. One

example is Beethoven’s cadenza on Mozart’s D

minor Concerto No. 20, where the cadenza is not

consistent with Mozart’s own style. Pianists of the

twentieth century, such as Vladimir Horowitz,

modified Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in C

Fazil Say and His Musical Identity: Musical Embellishments in “Black Earth”

229

sharp minor using challenging playing techniques,

resulting in a cadenza that was more virtuosic than of

Liszt himself. It is evident that modifications of the

score were needed for performers to showcase their

ability and skills as a virtuoso (Hamilton, 2008).

What about the twenty first century pianists? Should

pianists also modify the scores? If so, what types of

modifications or embellishments should they choose

to modify?

2.4 The Piano Work “Black Earth”

Kara Toprak is a well-known song by a Turkish blind

composer and poet, Aşik Veysel (1891-1973). Kara

Toprak inspired Fazil Say to compose his version of

Black Earth, which was written in 1997. Veysel’s

song is about loneliness and loss; the poem laments

the loss of life on earth (Otten, 2011). Say, however,

describes his piece, “Black Earth”, as a lonely journey

of an artist in the twenty-first century (Otten, 2011).

He plays this piano work as part of his program, and

it is also one of his popular encores. Fazil Say has

performed this piece for several years and we assume

that he has explored several interpretations based on

his performances. Therefore, we chose this piece for

this paper to unveil his embellishments in his piano

work and performance

3 DATA COLLECTION

There are four live-recorded performance of Fazil Say

performing “Black Earth” from the years 2007, 2015

and 2017. In 2015, we selected two recordings in

different venues. In 2007, he performed in Tokyo, and

in later years, Frankfurt and Bucharest in 2015, and

again in Frankfurt in 2017. These have been

published as full-length recordings on his official

YouTube channel.

We compared his melodic and rhythmic

modifications with the corresponding scores

published by Schott (2007). We notated the

modifications of each recording through software

known as Tune Transcriber, which can decrease the

tempo without changing the original pitch. Through

this process, we were able to listen in fragments and

notate the differences in the performances.

4 ANALYSIS

Our method was to notate the modifications of

melodic and rhythmic fragments performed by Fazil

Say during live-recorded performances. Melodic and

Rhythmic Modifications. “Black Earth” is a three-

part ballad with microtones, modal phrases, jazz

fragments and prepared keys or extended techniques.

The tempo indication in the introductory section is

Lento (Quasi improvvisazione) with no specific time

signature written. The term (Quasi improvvisazione)

resembles an improvisation. In this work, he applies

an extended technique, an imitation of the Bağlama

effect, a stringed instrument from Turkey, which is

also known as the saz. In the introduction section, Say

begins with a dark colour and soft dynamics. His

repetition of melodic fragments is inconsistent and

different from the music score, played either with

augmentation or diminution. There are five

repetitions of the notes in the melodic fragments

written in the score at Figure 1. This was the original

number of repetitions, whereas the longest was is in

2015 in Frankfurt at Figure 3, with nine repetitions of

the notes. However, in 2017, he shortens the

fragments to eight repetitions shows at Figure 5. The

examples of the augmentation and diminution in

comparison to the music score and his performances

at bar 4 is shown in Figure 1 to 5:

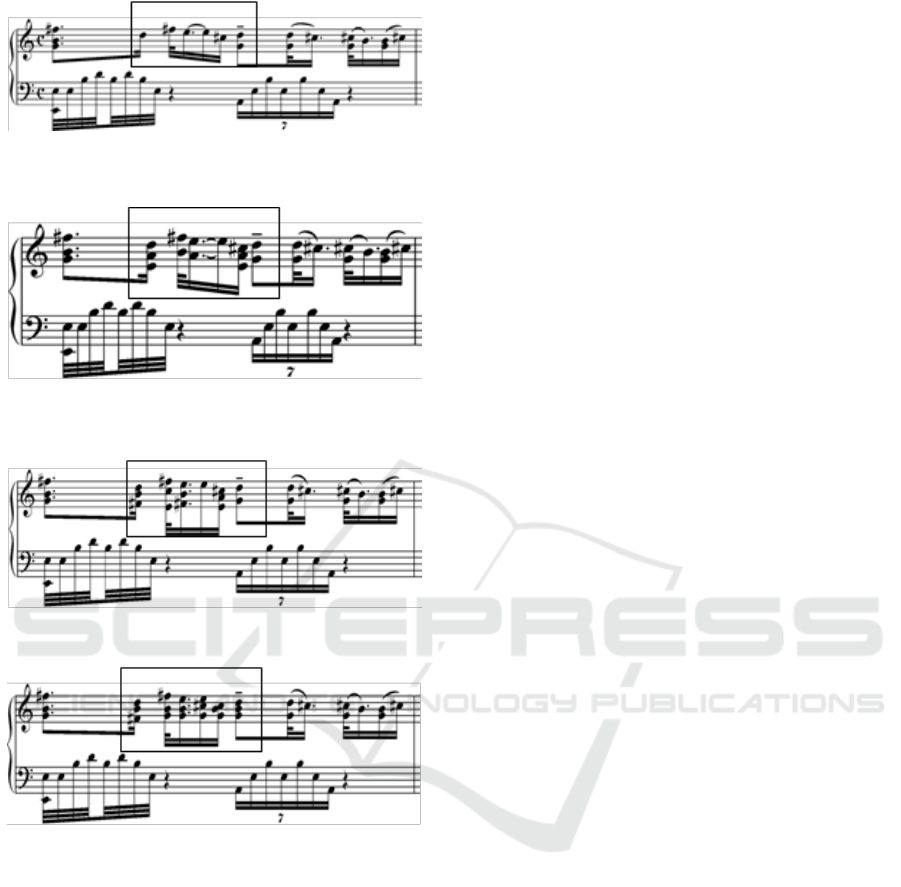

Figure 1: 5 notes repetitions from the Schott Publication

(2007)

Figure 2: 6 notes repetitions in Tokyo (2007)

Figure 3: 9 notes repetitions in Frankfurt (2015)

Figure 4: 8 notes repetitions in Bucharest (2015)

Figure 5: 9 notes repetitions in Frankfurt (2017)

Another example of Say’s modifications of

melodic and rhythmic fragments is in bar 8. The

original melodic fragments in Schott publication have

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

230

three repetitions of D, C sharp, D, two of the E notes

shows in Figure 6. He modifies from the written score

and remain the same of 4 notes repetitions in

Bucharest, year of 2015 shows in Figure 9, and in

Frankfurt, year of 2017 shows in Figure 10. He also

modifies the rhythmic pattern from quavers to

syncopated rhythms in two of his performances

(Frankfurt and Bucharest, both in 2015). However, in

Tokyo, he adds a crotchet at the end of the phrase and

sounds slightly longer, that difference from the other

performances.

melodic fragments rhythmic fragments

rhythmic fragments

Figure 6: 3 melodic fragments repetitions and quavers

rhythm fragments in Schott Publication (2007)

melodic fragments rhythmic

rhythmic fragments fragments

Figure 7: 5 melodic fragments repetitions and quavers

rhythmic fragments in Tokyo (2007)

melodic rhythmic

fragments fragments

Figure 8: 5 melodic fragments repetitions and syncopated

rhythmic fragments in Frankfurt (2015)

melodic rhythmic

fragments fragments

Figure 9: 4 melodic fragments repetitions and syncopated

rhythmic fragments in Bucharest (2015)

melodic rhythmic

fragments fragments

Figure 10: 4 melodic fragments repetitions and quavers

rhythmic fragments in Frankfurt (2017)

In the introduction, Say modifies several rhythmic

patterns that are mostly syncopated. He also changes

the triplets from bar 8 to quavers in four of his

performances. His melodic fragments are

inconsistent; he either expands or shortens the

fragments in each of his performances.

After the Quasi improvvisazione in the

introduction section, there are eight bars in the second

section which have a different tempo indication,

marked as Largo doloroso. In bar 11, the rhythm on

the first beat changes to a smaller value. He also

modified the B natural to a C sharp during his

performances in Tokyo, and later in Frankfurt (twice).

An example of each performances of the rhythmic

and note changes in bar 11 are shown in Figure 11 and

12:

Figure 11: The original notations from Schott Publication

(2007)

Figure 12: The rhythmic and pitch modifications in Tokyo

(2015) and both Frankfurt (2015 and 2017) in bar 11.

Another example of modifications is in bar 14.

The melody was played with additional chords rather

than single notes in three of his performances except

in Tokyo. The chord changes were not the same in

each performance. Figure 14 shows the chord

changes but remain the same rhythmic pattern with

the written score. Figure 16 shows that he adds the

chords at the fullest in Frankfurt in year 2017. As the

melody, tempo and dynamics were gradually

increased in the jazz style fragments, the tempo began

to change to a dramatic and energetic mood, which

led him to add those chords. He produced a bigger

sound to prepare for the mood changes. An example

of the additional chords in bar 14 are shown at Figure

14 to Figure 16:

Fazil Say and His Musical Identity: Musical Embellishments in “Black Earth”

231

Figure 13: The original notations from Schott Publication

(2007)

Figure 14: Additional of chords in Frankfurt (2015)

Figure 15: Additional of chords in Bucharest (2015)

Figure 16: Additional of chords in Frankfurt (2017)

In the third section, the tempo changes to Allegro

assai-Drammatico, with syncopated rhythms in the

bass lines to keep the jazz-like pulse steady. There are

no major embellishments or modifications in this fast

tempo section. As this section repeats in a similar

manner to the second section, there is an extension of

the rhythmic fragments and additions of melodic

fragments and arpeggiated chords during these

performances.

5 DISCUSSION

In this study, we analysed the embellishments from a

music score and compared these with those in the four

live-recorded performances by Fazil Say. Our

analysis shows that there were several melodic and

rhythmic modifications that occurred in each

performance. Fazil Say frequently applied the

extension of melodic fragments that were inconsistent

in terms of note repetitions. Some changed and some

were similar in each of his live performances. He

changed the notes which remained the same in three

of his performances. The addition of chords in a

second section of the piece, created a vast sound with

minor changes of harmony in each performance.

There were also several rhythmic modifications

that occurred during the performances that were

similar to each other. In this piece, Say simply played

syncopated rhythms and chose smaller values from

the original. He also changed a group of triplets to

quavers in the introduction section of the score, in

four of his performances, generating a more excited

feel in each of his performances.

It is evident that Say interprets and embellishes

differently in each of his performances. There is a

possibility that he creates the embellishment

spontaneously through inconsistency of fragments

and notations. The consistent fragments are not too

revealing and perhaps he does this intentionally.

“Black Earth” was published 10 years after his

composition and perhaps the publisher might

consider revising the music score.

Say’s embellishments consist of additional notes

and rhythmic modifications. Through our

observations, his embellishments resemble the

Baglama instrument effects especially at the Quasi

improvvisazione. The notes repetitions resemble the

Taksim. According to the Turkish Music Dictionary

website, the definition of Taksim is ‘a free-meter

instrumental improvisation section in Turkish

classical music. The modification in Say’s

performances only happens in a slow tempo. In

comparison with the western classical practice, this

was a common practice during the Baroque period

where embellishments apply in the slow movements

of sonatas (Rowland, 2001). Furthermore, the

composer has indicated the work should be played

Quasi improvvisazione, (like improvisation).

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we characterized Say’s commonly used

embellishments in “Black Earth”. As the term

embellishment means a ‘decoration’ and ‘to make

something beautiful’, the embellishments can be a

combination of Western and other embellishments

originating from other styles. In this study, we

ICONARTIES 2019 - 1st International Conference on Interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities

232

conclude that Fazil Say’s embellishments

consideration reflects his originality in comparison

through his piano work of the Black Earth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our institutions, Sultan Idris Education

University, Malaysia, and the MARA University of

Technology, Malaysia for their support of this study.

REFERENCES

Bach, CPE., 1974. Essay on the true art of playing keyboard

instruments. (W. J. Mitchell, Ed., & W. J. Mitchell,

Trans.) London: Ernst Eulenburg Limited.

Davidović, I., 2016. Chopin in Great Britain,1830 to 1930:

Reception, performance, recordings. Doctor of

Philosophy, University of Sheffield, Music

Department, Sheffield.

Donington, R., 2001. January 21. Groove music online.

Retrieved November 18, 2018 from Oxford Music

Online: https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.

article.08 765

Hamilton K., 2008, After the Golden Age:Romantic

Pianism and Modern Performance. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Hamilton, K. (1998). The virtuoso tradition. In D. Rowland,

& D. Rowland (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the

Piano (Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/

core/books/the-cambridge-companion-to-the

piano/FAFFE64B2A2D7E8C217FEB10B46A86B3

ed., pp. 57-74). Cambridge, United Kingdom:

Cambridge University Press.

Hellaby J., 2009. Modifying the Score.

Music Performance Research, 3, 1-21.

Turkish music dictionary. Retrieved July 27, 2019 from

Turkish music portal: http://www.turkishmusic

portal.org/en/turkish-music- dictionary

Otten J., 2011. Fazil Say: Pianist, Komponist, Welbürger.

Leipzig: Henschel-verlag.

Rowland, D. (2001). Early keyboard instruments; A

practical guide. Cambridge, United Kingdom:

Cambridge University Press.

The Frankfurt Radio Symphony, 2017. Say: Black Earth.

Fazil Say. Available at https://www.youtube.com/

watch ?v=gYtybgToH2Q (Accessed on 16 July 2018)

The Age of Music, 2015, Fazil Say-Black Earth-George

Enescu Festival 2015. Available at:

ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDhckqNAYD0

(Accessed on 24 July 2018)

Формат, 2015, Fazil Say-Black Earth. Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t6DRDw8RJfA

(Accessed on 10 July 2018)

Fazil Say, 2007. Fazil Say-Black Earth/Kara Toprak.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=

KG9wifgWdAQ (Accessed 5 July 2018)

Fazil Say and His Musical Identity: Musical Embellishments in “Black Earth”

233